Abstract

Objective

We describe the characteristics of the 15 patients with fingolimod-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) identified from the Novartis data safety base and provide risk estimates for the disorder.

Methods

The Novartis safety database was searched for PML cases with a data lock point of August 31, 2017. PML classification was based on previously published criteria. The risk and incidence were estimated using the 15 patients with confirmed PML and the overall population of patients treated with fingolimod.

Results

As of August 31, 2017, 15 fingolimod-treated patients had developed PML in the absence of natalizumab treatment in the preceding 6 months. Eleven (73%) were women and the mean age was 53 years (median: 53 years). Fourteen of the 15 patients were treated with fingolimod for >2 years. Two patients had confounding medical conditions. Two patients had natalizumab treatment. This included one patient whose last dose of natalizumab was 3 years and 9 months before the diagnosis of PML. The second patient was receiving fingolimod for 4 years and 6 months, which was discontinued to start natalizumab and was diagnosed with PML 3 months after starting natalizumab. Absolute lymphocyte counts were available for 14 of the 15 patients and none exhibited a sustained grade 4 lymphopenia (≤200 cells/μL).

Conclusions

The risk of PML with fingolimod in the absence of prior natalizumab treatment is low. The estimated risk was 0.069 per 1,000 patients (95% confidence interval: 0.039–0.114), and the estimated incidence rate was 3.12 per 100,000 patient-years (95% confidence interval: 1.75–5.15). Neither clinical manifestations nor radiographic features suggested any unique features of fingolimod-associated PML.

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a rare opportunistic infection of the CNS caused by reactivation of a latent John Cunningham virus (JCV), with a prevalence of 0.2 cases per 100,000 persons in the general population.1 In 2005, PML was confirmed in 3 patients participating in natalizumab clinical trials of multiple sclerosis (MS)2,3 and Crohn disease,4 disorders that were not previously associated with PML. As of August 2017, 749 confirmed cases of PML associated with natalizumab have been reported5 and, further, in 5 dimethyl fumarate–treated patients with MS.6 This has raised the possibility that there has been an increased risk of PML in patients with MS treated with immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory agents.

Fingolimod is a sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator approved for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS. Fingolimod prevents the egress of T and B lymphocytes from lymph nodes and reduces the infiltration of autoaggressive cells into the CNS.7,8

Although peripheral blood lymphocyte counts declined by 73% from baseline values within 1 month of drug initiation,9,10 consistent with the pharmacodynamic action of fingolimod, serious or opportunistic infections have only been infrequently observed in the postmarketing setting. To date, no correlation has been shown between absolute lymphocyte counts and the incidence of serious or opportunistic infections. Since 2015, PML cases not attributed to prior exposure to immunosuppressants have been reported in fingolimod-treated patients. The US prescribing information was subsequently updated to include opportunistic infections including PML.11 Herein, we describe the characteristics of 15 PML cases reported in fingolimod-treated patients with MS.

Methods

The Novartis safety database was searched for PML cases using the following search terms (MedDRA [Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities], version 19.1) with a data lock point of August 31, 2017: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, leukoencephalopathy, leukoencephalomyelitis, and JC virus granule cell neuronopathy. The PML cases were classified as “definite,” “probable,” “possible,” or “not PML” based on the criteria presented by Berger et al. in 2014,12 by an adjudication committee comprising experts in MS and PML. This classification is based on JCV DNA PCR status of CSF, MRI findings, and clinical presentation.

Overall patient exposure estimates were determined based on a combination of patient exposure to fingolimod in clinical trials together with an estimate of postmarketing patient exposure (which is calculated based on worldwide sales volume in kilograms of active substance sold during the period and the defined daily dose of 0.5 mg).

The incidence of PML in patients treated with fingolimod was estimated using the 15 confirmed PML cases and an overall population of patients treated with fingolimod. Patient characteristics were compiled based on the pharmacovigilance reports from the treating physicians held in the Novartis safety database, and patient identifiers are not revealed.

Data availability

These data are not from a clinical trial or specific study setup. It is rather based on postmarketing spontaneous reports made to Novartis in the context of routine pharmacovigilance. This reporting comes from various regions/countries with their respective data privacy laws. Data available in the Novartis safety database have been used to describe the carefully deidentified individual cases, and as such, no further data will be shared in either a repository or on request.

Results

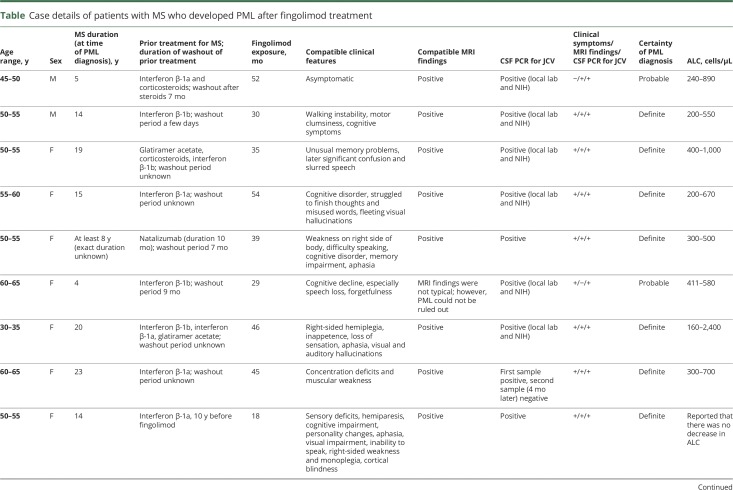

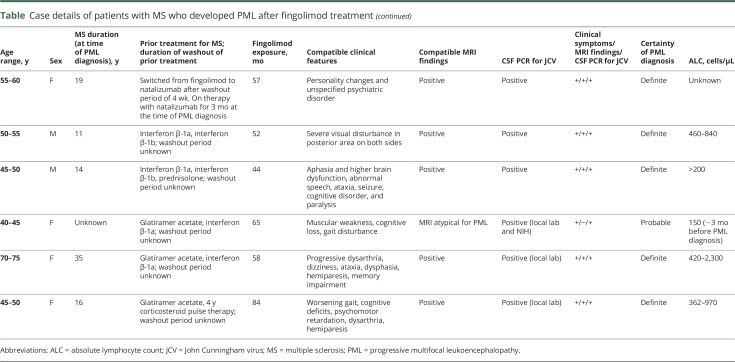

In total, 15 confirmed PML cases—12 “definite” and 3 “probable”—for which prior immunotherapy is not implicated, were identified in the real-world setting. Based on data from 15 confirmed PML cases associated with fingolimod treatment alone, the estimated risk is 0.069 per 1,000 patients (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.039–0.114) and the estimated incidence rate is 3.12 per 100,000 patient-years (95% CI: 1.75–5.15). Details of the clinical features of the 15 PML cases are shown in the table.

Table.

Case details of patients with MS who developed PML after fingolimod treatment

Demographics and baseline characteristics

The patients were geographically dispersed across Europe (n = 6), North America (n = 5), and Asia (n = 4). Of the 15 patients, 11 were women. The mean patient age was 53 years (median: 53 years) and 5 patients were younger than 50 years. The duration of MS in these patients ranged from 4 to 35 years (considering those with known year of MS onset). Of the 15 patients with PML, 2 presented with confounding medical conditions (one with previous cancer and one patient with ulcerative colitis with prior immunosuppressive therapy). In addition, there were 2 patients who had received therapy with natalizumab; however, the contributory role of fingolimod in the occurrence of PML could not be excluded in these cases. The first patient had previous natalizumab exposure for 10 months, which was discontinued for 7 months, and then the patient received fingolimod treatment for 38 months before PML diagnosis. The second patient was receiving fingolimod for 4 years, 6 months, which was discontinued to start natalizumab and was diagnosed with PML 3 months later. Fourteen of the 15 patients were exposed to fingolimod for >2 years. Based on the available reported absolute lymphocyte counts in 14 of 15 patients, 4 of the patients exhibited grade 4 lymphopenia (≤200 cells/μL). Previous MS treatments included natalizumab, interferons, corticosteroids, and glatiramer acetate, with no clinically identifiable patterns.

Virologic characteristics

To date, there is only limited sequence information on the JCVs associated with PML in fingolimod-treated patients with MS who developed PML.

PML clinical features and diagnosis

Heralding manifestations of PML at the time of clinical presentations included walking instability, weakness, memory problems, confusion, dysarthria, visual hallucinations, cognitive impairment, speech disturbances, concentration deficits, and visual impairment. One patient was clinically asymptomatic at presentation, and the disorder was diagnosed radiographically. No identifiable pattern was observed in clinical symptoms at presentation.

Brain MRIs were consistent with PML in 13 of the 15 cases and showed varying presentations, ranging from few but extending lesions to multiple lesions extending into adjacent lobes, cortical, subcortical, and juxtacortical regions, and sometimes ill-defined lesions, described with and without microcysts. Some images showed strong hyperintense diffusion-weighted imaging signals, whereas others were without clear diffusion signals.

PCR results for JCV DNA in the CSF were positive in all 15 patients when tested at local laboratories and/or at the NIH reference laboratory (Bethesda, MD). Serology for serum JCV antibodies was reported for 8 of the 15 patients and was positive in all.

Treatment and clinical outcome

Treatment with fingolimod was discontinued in all patients, and subsequent therapies for PML included mefloquine, mirtazapine, and cidofovir in varying combinations. Three of the PML cases were fatal. Most patients were reported to be clinically stable or with slightly improving neurologic functions or with deficits including aphasia, mobility, and cognition.

Discussion

In total, 15 patients with PML occurring in association with fingolimod administration alone were identified in the Novartis safety database, including 12 “definite” and 3 “probable” cases, by August 2017. This included 6 cases that have been published in the literature.13–18 The overall rate of PML with fingolimod treatment is estimated to be <1:10,000 patients, which was considered low risk in a recent article that classified the risk of PML with current disease-modifying therapies.19 The current estimated risk of PML with fingolimod treatment is 0.069 (95% CI: 0.039–0.114) per 1,000 patients and the incidence rate is 3.12/100,000 patient-years.

There are limitations for these risk estimates in that they are solely based on the PML cases spontaneously reported to Novartis from the postmarketing setting. Another potential limitation is the estimate of patient exposure data, which are derived from sales data. PML is a rare, serious opportunistic infection with high awareness in the MS community; thus, the probability of physicians reporting these cases is good. The reporting rate over time has remained constant, thus suggesting that cases of PML are being reported.

In a recent review,19 the risk of PML stratified by various disease-modifying therapies used in patients with MS suggested that natalizumab is associated with a significantly higher risk of PML. Fingolimod and dimethyl fumarate are associated with significantly lower risks. Alemtuzumab, mitoxantrone, rituximab, and teriflunomide have a potential risk of PML because all of these agents are associated with the risk of PML when used in treatment regimens/indications other than MS or have a related compound with which PML has been observed. For newer compounds, such as daclizumab and ocrelizumab, clinical experience is very limited and the associated PML risk is unknown. The current risk of PML with fingolimod is very low; to date, only 15 cases have been reported. Moreover, the few cases observed and evaluated so far do not allow the identification of any evidence-based specific guidance to form monitoring and risk-mitigation strategies for fingolimod. However, certain risk mitigation strategies have been proposed for other drugs with a larger number of such cases or a potentially clearer correlation with their mode of action, such as routine JCV antibody testing or specific lymphocyte cutoffs. However, the value of such guidance systems and their ability to prevent additional PML cases is yet to be proven. So far, the risk stratification algorithm has not led to any marked reduction in the incidence of PML in natalizumab-treated patients.20 Another previous report suggested that, although a decrease in the incidence of PML has not been noted, the rate of incidence increase has certainly reduced significantly between 2013 and 2016, after the introduction of the Stratify JCV assay.21 Nevertheless, JCV antibody status should be retested regularly considering the false-negative rates and the potential for seroconversion.22,23

The number of PML cases reported so far with fingolimod is too low to trigger any specific interventions at this point in time. Guidelines that are not evidence-based may result in an additional burden for patients with uncertain benefits, including the risk of inappropriate modification of an effective MS therapy, which in itself carries the risk of increasing morbidity in such patients. At present, no PML risk stratification methodology has been identified for patients treated with fingolimod. However, risk mitigation is focused on increased awareness and education of patients and prescribers regarding such cases because, in most instances, early diagnosis and appropriate management are key to improved therapeutic outcomes.

The clinical signs and symptoms of PML often resemble those observed with an MS relapse; however, in contrast to an MS relapse, these tend to be slowly and persistently progressive in nature. Physicians should keep this in mind when investigating patients for PML and must look for features that distinguish PML from other differential diagnoses including MS. In a PML case series consisting of 28 patients,24 typical clinical presentation included neurobehavioral, motor, language, and visual symptoms, with cognitive changes being more prominent. Acute or subacute cognitive changes, language disturbances, and seizures should serve as “red flags” for the possibility of PML. Optic neuritis and myelopathy would not be anticipated as clinical manifestations of PML.

MRI scans offer a sensitive tool in the diagnosis of PML. Typical PML lesions are diffuse, subcortical, and located exclusively in the white matter. These lesions appear as single or multiple hyperintense areas in T2-weighted images, which become confluent and large with disease progression. MRI contrast enhancement is believed to be minimal or absent in PML25; however, in AIDS-associated PML, 10% of patients exhibited contrast enhancement on CT scans and 15% on MRI with gadolinium.26 In natalizumab-associated PML, 43% of cases showed gadolinium contrast enhancement at the time of diagnosis.24 Although contrast enhancement alone cannot be used as a feature to distinguish an MS relapse from PML, patterns of contrast enhancement, the nature and location of the lesions, and the presence of a dark rim around the lesions on susceptibility weighted imaging or gradient echo imaging may be helpful in distinguishing the demyelinating lesions of PML from those of MS.27,28

As of August 2017, approximately 217,000 patients have been treated with fingolimod in both clinical trials and postmarketing settings, and the total patient exposure exceeds 480,000 patient-years. Although the risk of PML with fingolimod treatment is considered very low, vigilance toward PML is required for all patients irrespective of the low risk. The current understanding of the mechanism of action of fingolimod does not provide a convincing causal link between fingolimod treatment and the incidence of PML. Fingolimod has been shown to prevent the egress of CCR7+ve naive T cells and central memory T cells from lymph nodes, sparing CCR7−ve effector memory T cells.29 The redistribution of CD4+ central memory T cells from circulation to lymphatic organs may contribute to the development of PML. In some cases, because of its partial sequestration of effector memory T cells, fingolimod may have a contributory role to other factors in reducing immune response to JCV reactivation. Isolating and fully characterizing the viruses in cases of fingolimod-associated PML may assist in understanding the disease pathogenesis with fingolimod.

Based on available data, there appear to be no clinically or radiographically unique features of fingolimod-associated PML. The sex distribution is concordant with the overall fingolimod-treated population. Ten of the 15 patients were older than 50 years at the time of PML diagnosis. Although an exact relationship with fingolimod treatment duration cannot be elucidated, all 15 cases occurred after 18 months or more of treatment. There appears to be no correlation with profound lymphopenia and lymphocyte subsets (CD4, CD8, and CD4/8 ratios) in fingolimod-treated patients, and this is not believed to be informative of PML risk. Treating physicians should be vigilant for signs and symptoms suggestive of PML in all patients who are being treated with fingolimod. As soon as PML is suspected, the drug should be discontinued until it has been ruled out. Early diagnosis is critical for better clinical outcomes. Unfortunately, there is no established treatment for PML,30 and at this point of time, no treatment recommendations can be made based on the limited number of cases seen.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Sreelatha Komatireddy (Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, India) for assistance with formatting the manuscript.

Glossary

- CI

confidence interval

- JCV

John Cunningham virus

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PML

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation, and provided critical review during the preparation of the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript for intellectual content, provided guidance during manuscript development, and approved the final version submitted for publication. The final responsibility for the content lies with the authors.

Study funding

No targeted funding reported.

Disclosure

J. Berger reports grants from Biogen and TEVA; personal fees from Biogen, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme, Millennium/Takeda, Novartis, Inhibikase, Excision Bio, Roche, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Alkermes, and Bayer. B. Cree reports personal fees from Biogen, EMD Serono, GeNeuro, Novartis, and Sanofi Genzyme. B. Greenberg reports personal fees from Novartis, Alexion; grants from MedImmune, Chugai, and Genentech. B. Hemmer reports grants from Chugai, Roche, and MedImmune; personal fees from Roche and Allergy Therapeutica; personal fees and nonfinancial support from Biogen, Merck, Bayer, and Teva. He was funded by the German MS Competence Network, the Transregional Research Center TR118, and the EU project Multiple MS. B. Ward reports personal fees from Novartis. V. Dong is an employee of Novartis. M. Merschhemke is an employee of Novartis. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Palazzo E, Yahia SA. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in autoimmune diseases. Joint Bone Spine 2012;79:351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N Engl J Med 2005;353:375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med 2005;353:362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tysabri Safety Update [online]. Available at: medinfo.biogen.com/secure/download?doc=workspace%3A%2F%2FSpacesStore%2Fa22baae1-7220-416c-8c2c-28c42cdacff8&type=pmldoc&path=null&dpath=null&mimeType=null&Continue=Continue. Accessed July 21, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biogen. Tecfidera (Dimethyl Fumarate): PML Case Reports. Available at: medinfo.biogen.com. Accessed January 9, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkmann V, Davis MD, Heise CE, et al. The immune modulator FTY720 targets sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem 2002;277:21453–21457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science 2002;296:346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:402–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010;362:387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.GILENYA [prescribing information]. Available at: www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/gilenya.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger JB. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. In: Tselis AC,Booss J, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V.; 2014:357–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gyang TV, Hamel J, Goodman AD, Gross RA, Samkoff L. Fingolimod-associated PML in a patient with prior immunosuppression. Neurology 2016;86:1843–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calzado G, Virgós T, Bullejos M, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with fingolimob use in a patient with multiple sclerosis without previous exposure to immunosuppressant drugs. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2016;23:A156. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kume K, Takada T, Kawakita R, et al. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient who was receiving fingolimod. Neurol Ther 2016;33:S253. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakahara J, Kufukihara K, Tanikawa M, et al. Third Japanese case of fingolimod-associated PML in natalizumab-naive MS: coincidence or alarm bell? (P762). Mult Scler J 2017;23 (Suppl 3):382–3. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishiyama S, Misu T, Shishido-Hara Y, et al. Fingolimod-associated PML with mild IRIS in MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2018;5:e415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi F, Turazzini M, Ricci S, et al. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in patient with fingolimod treatment: one-year follow-up. Mult Scler J 2017;23:680–975. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berger JR. Classifying PML risk with disease modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2017;12:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cutter GR, Stuve O. Does risk stratification decrease the risk of natalizumab-associated PML? Where is the evidence? Mult Scler 2014;20:1304–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campagnolo D, Dong Q, Lee L, Ho PR, Amarante D, Koendgen H. Statistical analysis of PML incidences of natalizumab-treated patients from 2009 to 2016: outcomes after introduction of the Stratify JCV® DxSelect™ antibody assay. J Neurovirol 2016;22:880–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorelik L, Lerner M, Bixler S, et al. Anti-JC virus antibodies: implications for PML risk stratification. Ann Neurol 2010;68:295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Outteryck O, Zephir H, Salleron J, et al. JC-virus seroconversion in multiple sclerosis patients receiving natalizumab. Mult Scler 2014;20:822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clifford DB, De Luca A, Simpson DM, Arendt G, Giovannoni G, Nath A. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: lessons from 28 cases. Lancet Neurol 2010;9:438–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahraian MA, Radue EW, Eshaghi A, Besliu S, Minagar A. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: a review of the neuroimaging features and differential diagnosis. Eur J Neurol 2012;19:1060–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger JR, Pall L, Lanska D, Whiteman M. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with HIV infection. J Neurovirol 1998;4:59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yousry TA, Pelletier D, Cadavid D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging pattern in natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 2012;72:779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hodel J, Outteryck O, Verclytte S, et al. Brain magnetic susceptibility changes in patients with natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015;36:2296–2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehling M, Brinkmann V, Antel J, et al. FTY720 therapy exerts differential effects on T cell subsets in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2008;71:1261–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics 2017;14:961–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

These data are not from a clinical trial or specific study setup. It is rather based on postmarketing spontaneous reports made to Novartis in the context of routine pharmacovigilance. This reporting comes from various regions/countries with their respective data privacy laws. Data available in the Novartis safety database have been used to describe the carefully deidentified individual cases, and as such, no further data will be shared in either a repository or on request.