Abstract

Objective

Using a science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM) curriculum, we developed, piloted, and tested the Headache and Arts Program. This program seeks to increase knowledge and awareness of migraine and concussion among high school students through a visual arts–based curriculum.

Methods

We developed a 2-week Headache and Arts Program with lesson plans and art assignments for high school visual arts classes and an age-appropriate assessment to assess students' knowledge of migraine and concussion. We assessed students' knowledge through (1) the creation of artwork that depicted the experience of a migraine or concussion, (2) the conception and implementation of methods to transfer knowledge gained through the program, and (3) preassessment and postassessment results. The assessment was distributed to all students prior to the Headache and Arts Program. In a smaller sample, we distributed the assessment 3 months after the program to assess longitudinal effects. Descriptive analyses and p values were calculated using SPSS V.24 and Microsoft Excel.

Results

Forty-eight students participated in the research program. Students created artwork that integrated STEAM knowledge learned through the program and applied creative methods to teach others about migraine and concussion. At baseline, students' total scores averaged 67.6% correct. Total scores for the longitudinal preassessment, immediate postassessment, and delayed 3-month postassessment averaged 69.4%, 72.8%, and 80.0% correct, respectively.

Conclusion

The use of a visual arts–based curriculum may be effective for migraine and concussion education among high school students.

Migraine and concussion are highly disabling conditions that are underrecognized and undertreated.1,2 WHO defines migraine as the sixth most disabling condition.3 Children and adolescents experience adverse physical and mental health outcomes, hindrances on school performance, and negative effects on quality of life.4–6 In adolescent girls and boys, the mean prevalence of migraine is 10.5% and 7.6%, respectively, whereas in adulthood, prevalence is 18% of women and 6% of men.7,8 Despite its prevalence, migraine remains substantially underdiagnosed and undertreated in youths due to knowledge gaps among students and parents.9

Similar complications exist for concussion, as most students lack the basic awareness needed to recognize and respond to concussion injuries. Further concussion education is thus essential.10 Currently, few studies assess the effect of concussion education programs, and existing programs are generally limited to student athlete groups; no high school–based programs address migraine education.11–14 Broader, school-based education programs have proven effective for disseminating important various health concepts.15–18

Using the science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics initiative, which integrates the traditional science, technology, engineering, and mathematics curriculum with art and design, we developed and piloted the Headache and Arts Program to increase high school students' knowledge and awareness of migraine and concussion through the visual arts. Since adolescence is a period of peak incidence for migraine and concussion relative to other age groups, we chose to target high school students. We assessed students' knowledge through (1) the creation of artwork that depicted the experience of a migraine or concussion, (2) the conception and implementation of innovative methods to transfer knowledge gained through the program, and (3) preassessment and postassessment results.

Methods

Curriculum development

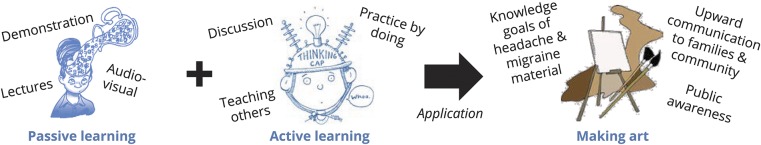

In preparation for this pilot and to gauge interest, a shorter, informal version of the current curriculum was taught to 9th-grade visual art students in one school during the 2014–2015 school year. This included lessons developed and taught by an art teacher, a presentation by a board-certified neurologist in headache medicine, and creation of artwork displayed at our Medical Center. Next, a formal curriculum was developed, including daily lesson plans, PowerPoint presentations, and an informative headache manual for art teachers (concept diagram: figure 1). Through a series of qualitative 1:1 interviews, detailed input from 3 current high school teachers and 4 high school students was obtained and incorporated into the curriculum through an iterative approach.

Figure 1. Concept diagram.

Assessment development

A board-certified neurologist with United Council of Neurologic Subspecialty Certification in Headache Medicine drafted an assessment designed to capture students' basic knowledge about migraine and concussion. To assess content validity, we distributed the assessment on the pediatric headache listserv of the American Headache Society. We received feedback from 5 pediatric headache specialists across the United States and adapted the assessment accordingly to ensure that we captured what they felt were the most important pieces of information and to ensure that they felt that the wording on the assessment was age-appropriate. We then conducted qualitative 1:1 interviews with 4 art teachers, 2 science teachers, and 5 high school students to ensure the use of age-appropriate vocabulary, language comprehension, and understanding of measured health concepts. Using an iterative, psychometric approach, we adapted the assessment following feedback from each student and teacher.

Population

Art teachers or school administrators of select New York City private schools were emailed program invitations during the 2016–2017 academic year. Public and private schools with a visual arts program and visual arts faculty were invited to participate. Upon New York City Department of Education institutional review board approval, select New York City public schools were emailed program invitations. Two private schools and 2 public schools opted to participate, including three 9th-grade classes, two 10th-grade classes, and one mixed 9th- and 10th-grade class. Two classes of 10th-grade students were used to assess the longitudinal effects of the program.

Program run

Consent and assent forms were sent home with the students in all participating art classes. Only students and parents who consented were involved in the research portion of the 2-week program. Publication permissions were obtained from some students. In week 1, students learned to draw a model of the brain, create textures with line patterns, and critique and research famous works of op art (optical illusion art). The neurologist taught one interactive lesson on migraine and concussion, during which students learned about the symptoms of migraine and concussion, prevention and treatment options, and the public health burden of these conditions. In week 2, all art students generated a work of op art that depicted the experience of a migraine or concussion using their own ideas synthesized from knowledge gained from the curriculum lesson. The works of art were displayed at the New York University Concussion Symposium and the New York University Neurology Research Symposium. Participating students and their families were invited to attend receptions to view the art displays.

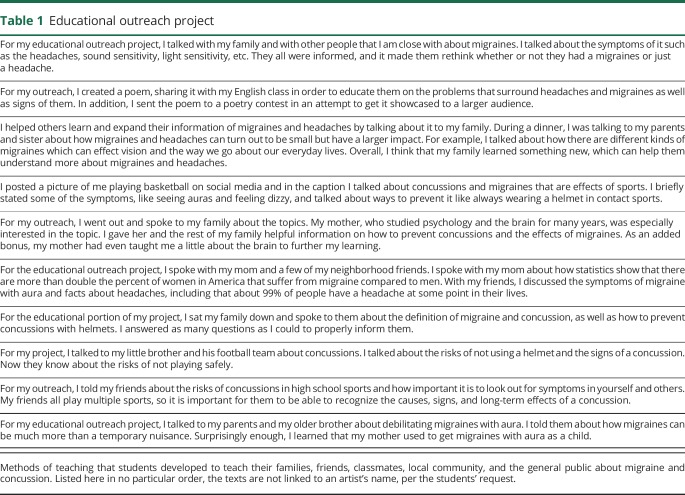

All students were assessed through a knowledge transference project, by which they were required to teach family or community members through a mechanism of their choice. As part of the research program, students were asked to complete a cross-sectional assessment immediately before and after the program. Students at one school were also asked to complete an assessment 3 months after the program. The purpose of the assessment was to assess what students know about migraine and concussion to aid in future program development.

Outcomes

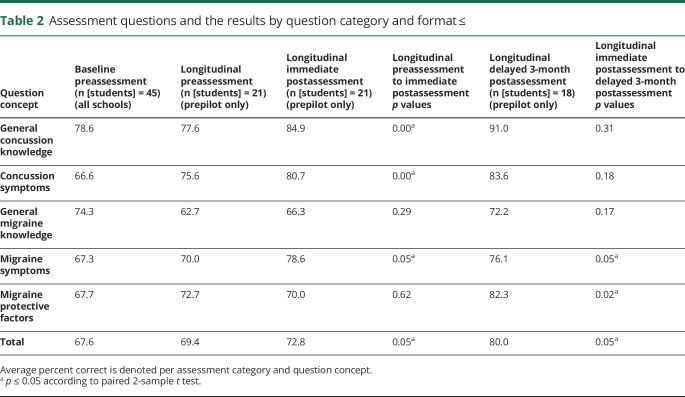

The first 2 outcomes were qualitative: artwork was required to depict the experience of a migraine or concussion and was assessed accordingly by each art teacher, and students were required to write a paragraph about their knowledge transference project in which they described their project and the success to which they were able to transfer their knowledge. Teachers assessed the assignments for completion. The third outcome was quantitative and was based on the scores on the assessments. The same assessment was delivered at each of the 3 assessment periods. Questions were grouped into 5 categories, including general concussion knowledge, concussion symptoms, general migraine knowledge, migraine symptoms, and migraine protective factors. Students were assessed on mean improvement within each category. Of note, the students were not given a sheet indicating the correct answers after each assessment period.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics in SPSS and paired 2-sample t tests (with p ≤ 0.05 significant) in Microsoft Excel. We collected baseline assessment results for all schools. Preassessment and postassessment analyses were conducted for one school only due to limitations of the academic year. Results were compared for preassessment vs postassessment and postassessment vs delayed 3-month postassessment. Assessments were scored on the basis of correctness, and answers that were left blank were marked as incorrect.

Data availability

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.

Results

Of all 4 participating schools, 48 students elected to enroll in the research program.

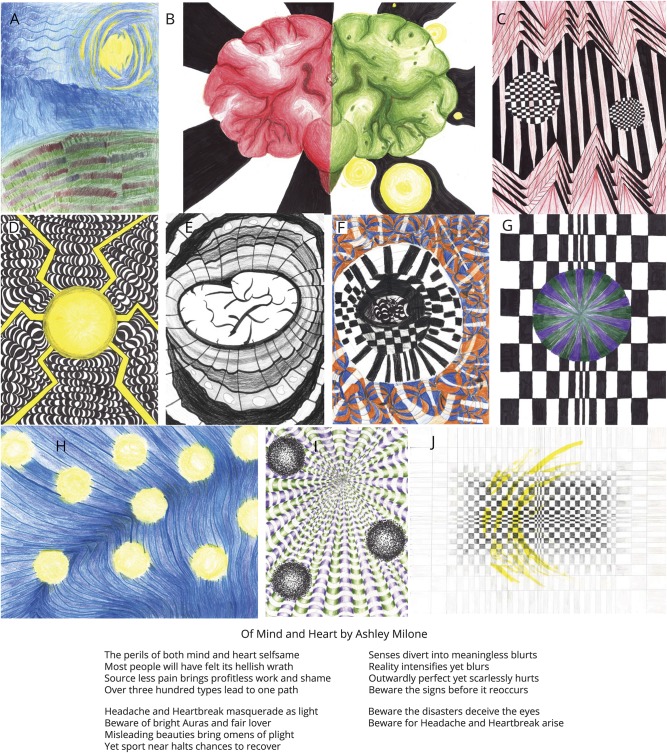

Artwork is displayed in figure 2. As part of the knowledge transference project, students developed unique methods of teaching their families, friends, classmates, local community, and the general public about migraine and concussion (table 1). One student wrote a poem that was submitted to a national poetry contest (figure 2). Another student created posts on Facebook to inform people about concussion. Posts included the following:

“Did you know: In children's cases, migraines are a problem and occur 1–2 hours shorter than in adults?”

“Did you know: One of the main causes for concussions is due to sports? Be sure to wear helmets.”

“Did you know: At least one person in every 4 households suffers from migraines?”

Figure 2. Student artwork from the headache and arts program.

Artist credits: (A) Alexander Alvarez, (B) Ashley Milone, (C) Katie Nakano, (D) Morgan Turner, (E) Steven Morris, (F) Richard Karnabi, (G) Jack Foulsham, (H) Sarah Marie Axiak, (I) Katherine Buttigieg, (J) Christian Conte.

Table 1.

Educational outreach project

We later sought feedback from the participating teachers. Comments included the following:

“So many parents commented on the program at parent teacher night.”

“There was a ripple effect [in the excitement]. I was pleasantly surprised that there was a ripple effect.”

Comments from parents included the following:

“I'm so glad that my child had the unique opportunity to be a part of this program.”

“My child appreciates art so much more since completing this program.”

“It was such a thrill to see my child's work in the culminating exhibition.”

Sixty-two percent (n = 30) of students completed 2 or more assessments to test their knowledge of migraine and concussion. Thirty-one percent (n = 15) completed one assessment. Three students did not complete any assessments. Table 2 shows a summary of assessment questions and the results by question category and format. At baseline, students' scores averaged 67.6% correct. Students' total scores for the longitudinal preassessment, immediate postassessment, and delayed postassessment averaged 69.4%, 72.8%, and 80.0% correct, respectively. These improvements generally appeared to be sustained in the group in which a 3-month postassessment was also conducted.

Table 2.

Assessment questions and the results by question category and format≤

Discussion

The use of a visual arts–based curriculum may be an effective medium for headache and concussion education among high school students. The artwork created demonstrated knowledge about the brain and how perception can be affected by brain disorders such as migraine and concussion, and the transfer of knowledge assignment generated innovative ideas, thereby indicating that students spread knowledge gained from the program. Our results from this assignment show that the Headache and Arts Program sparked conversations within families, sports teams, and friend groups, and led to public service announcements on social media (e.g., Facebook). Dissemination of the scientific knowledge about concussion and migraine enables more people to seek treatment when it may be needed. This is noteworthy given the stigma associated with concussion reporting among students and student–athletes for fear of consequences from athletic coaches or teachers due to the requirement for evaluation and possible removal from play or class.19–21 These data are also important given that there is concern about migraine and stigma, and because patients report decreased quality of life compared to their peers.22–24 Increased education and awareness among students and spread of this knowledge to their families could lead to increased diagnosis and treatment for migraine and concussion, thereby decreasing the time of onset to diagnosis for these conditions. Finally, despite our small sample size, there appeared to be improvement in knowledge based on differences in the preassessment and subsequent assessments.

A limitation of this study includes potential differences in baseline knowledge. We do not have these data available. In addition, since we administered the same assessment 3 times, there may have been testing effects, including practice effect bias and maturation bias. Therefore, some improvement may have been expected. Given academic year limitations, it is difficult to conduct a 3-month postprogram assessment within the classrooms if the program is not begun at the start of the year. Our small sample size may have limited our ability to detect additional significant findings on the assessment. However, the program has great potential given the transfer of knowledge activities done as a result of the program and the creative works of art created by students who participated in the program.

We have several ideas for future development of the Headache and Arts Program. To increase consent and assessment–return adherence among students, new versions of the program will include a student participation–based grading scheme for teachers. Based upon input from teachers and students, the program may be adapted to different teaching styles, including flipped classroom learning, and may be expanded beyond visual arts classes. A program website will be developed that will provide resources, such as a link for teachers and students to submit input about the program. Further study is needed in other settings to verify our findings. Interestingly, there appeared to be a high rate of baseline knowledge of concussion symptoms. This could be explored further to examine how it varies among schools. To assess the full potential effect of the program, additional studies must determine whether high school students can act as effective conduits of headache and concussion education in their families and communities and whether these efforts can translate into reduced public burden of these conditions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Judith Kaplan and Rachel Meuler for help with program development; and the Pediatric Section of the American Headache Society for their members' suggestions for the program assessment.

Author contributions

Mia Minen: study concept and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, critical revision of manuscript, study supervision. Alexandra Boubour: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data.

Study funding

This study was not funded. However, Dr. Mia Minen is a recipient of the American Academy of Neurology/American Brain Foundation Practice Research Training Fellowship, which provides salary support to allow her time to conduct research. In addition, Dr. Mia Minen is part of the Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program, which provides salary support to allow her time to conduct research.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Zhang AL, Sing DC, Rugg CM, Feeley BT, Senter C. The rise of concussions in the adolescent population. Orthop J Sports Med 2016;4:2325967116662458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straube A, Heinen F, Ebinger F, von Kries R. Headache in school children: prevalence and risk factors. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2013;110:811–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Headache disorders. 2016. Available at: who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs277/en/. Accessed June 20, 2016.

- 4.Arruda MA, Bigal ME. Behavioral and emotional symptoms and primary headaches in children: a population-based study. Cephalalgia 2012;32:1093–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kernick D, Reinhold D, Campbell JL. Impact of headache on young people in a school population. Br J Gen Pract 2009;59:678–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karwautz A, Wober C, Lang T, et al. Psychosocial factors in children and adolescents with migraine and tension-type headache: a controlled study and review of the literature. Cephalalgia 1999;19:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wober-Bingol C. Epidemiology of migraine and headache in children and adolescents. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2013;17:341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterlin BL, Gupta S, Ward TN, Macgregor A. Sex matters: evaluating sex and gender in migraine and headache research. Headache 2011;51:839–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span study. Cephalalgia 2010;30:1065–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Register-Mihalik JK, Guskiewicz KM, McLeod TC, Linnan LA, Mueller FO, Marshall SW. Knowledge, attitude, and concussion-reporting behaviors among high school athletes: a preliminary study. J Athl Train 2013;48:645–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cusimano MD, Chipman M, Donnelly P, Hutchison MG. Effectiveness of an educational video on concussion knowledge in minor league hockey players: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Echlin PS, Johnson AM, Holmes JD, et al. The sport concussion education project: a brief report on an educational initiative: from concept to curriculum. J Neurosurg 2014;121:1331–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagley AF, Daneshvar DH, Schanker BD, et al. Effectiveness of the SLICE program for youth concussion education. Clin J Sport Med 2012;22:385–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Echlin PS, Johnson AM, Riverin S, et al. A prospective study of concussion education in 2 junior ice hockey teams: implications for sports concussion education. Neurosurg Focus 2010;29:E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams O, Noble JM. “Hip-hop” stroke: a stroke educational program for elementary school children living in a high-risk community. Stroke 2008;39:2809–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worthington HV, Hill KB, Mooney J, Hamilton FA, Blinkhorn AS. A cluster randomized controlled trial of a dental health education program for 10-year-old children. J Public Health Dent 2001;61:22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willeford C, Splett PL, Reicks M. The great grow along curriculum and student learning. J Nutr Edu 2000;32:278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans D, Clark NM, Feldman CH, et al. A school health education program for children with asthma aged 8–11 years. Health Educ Behav 1987;14:267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace J, Covassin T, Beidler E. Sex differences in high school athletes' knowledge of sport-related concussion symptoms and reporting behaviors. J Athl Train 2017;52:682–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safai P. Healing the body in the “culture of risk”: examining the negotiation of treatment between sport medicine clinicians and injured athletes in Canadian intercollegiate sport. Sociol Sport J 2003;20:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young K, White P, McTeer W. Body talk: male athletes reflect on sport, injury, and pain. Sociol Sport J 1994;11:175–194. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdollahpour I, Salimi Y, Shushtari ZJ. Migraine and quality of life in high school students: a population-based study in Boukan, Iran. J Child Neurol 2015;30:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro RE, Reiner PB. Stigma towards migraine. Cephalalgia 2013;33:17. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brna P, Gordon K, Dooley J. Canadian adolescents with migraine: impaired health-related quality of life. J Child Neurol 2008;23:39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared by request from any qualified investigator.