Abstract

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a 21 amino acid peptide with diverse biological activity that has been implicated in numerous diseases. ET-1 is a potent mitogen regulator of smooth muscle tone, and inflammatory mediator that may play a key role in diseases of the airways, pulmonary circulation, and inflammatory lung diseases, both acute and chronic. This review will focus on the biology of ET-1 and its role in lung disease.

Keywords: asthma, endothelin, fibrosis, inflammation, pulmonary hypertension

Introduction

ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3 are members of a peptide family that has been the subject of much interest in the past decade. Our laboratory and that of Highsmith identified this peptide vasoconstrictor secreted from endothelial cells [1,2,3] that was subsequently isolated, sequenced, cloned, and named by Yanagisawa in 1988 [4]. The many diverse and overlapping functions of these peptides have since implicated endothelins in both homeostatic mechanisms as well as diseases of the lungs. This review will focus on the role of endothelins (particularly ET-1), emphasizing the need to better understand endothelin biology and function in a wide variety of disorders including diseases of the airways and pulmonary vasculature, lung tumors, the acute respiratory distress syndrome, and fibrotic diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Human diseases in which endothelin-1 may be implicated

| Airway diseases |

| Asthma |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| Bronchiectasis |

| Bronchiolitis obliterans |

| Parenchymal lung diseases |

| Pulmonary fibrosis |

| Idiopathic |

| Connective tissue associated |

| Neoplastic diseases |

| Lung malignancies |

| Metastases to lung |

| Pulmonary vascular diseases |

| Primary pulmonary hypertension |

| Secondary pulmonary hypertension |

| Connective tissue diseases |

| Congenital heart disease |

| Acute lung injury |

| Ischemia/reperfusion |

| Pulmonary edema |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| Sepsis |

| Lung transplant rejection |

| Acute: ischemia/reperfusion injury |

| Chronic: bronchiolitis obliterans |

Endothelin biochemistry

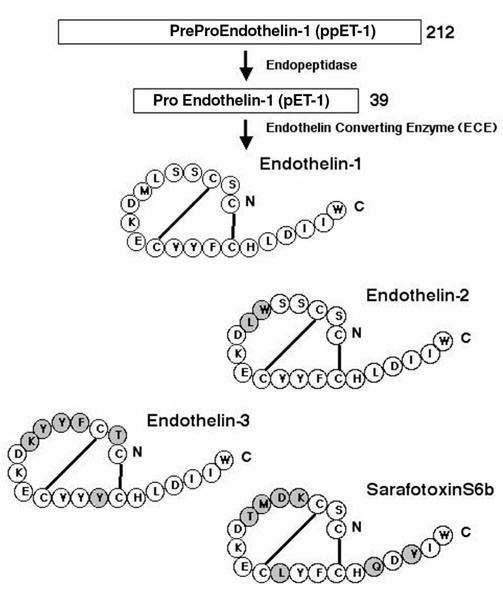

The endothelins are a family of 21 amino acid peptides, of which there are three distinct isoforms (ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3). The isoforms ET-2 and ET-3 differ from ET-1 by two and six amino acids, respectively, and share significant homology, especially at the carboxy terminus with sarafotoxins a-e (Fig. 1). Endothelin-1 is the most abundant isoform and has been best characterized. The lung has the highest levels of ET-1 secreted by endothelium, smooth muscle, airway epithelium, and a variety of other cells (Table 2). ET-1 also circulates in the plasma. In the normal lung, ET-1 mainly localizes to vascular endothelium, airway and vascular smooth muscle cells and, to a lesser degree, the epithelium. ET-2 has similar biologic functions as ET-1 and is found in the myocardium, kidney and placental tissues. ET-3 also circulates in plasma and is found in the central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, lung, and kidney although the cellular source is not clear. The gene for ET-1 is located on chromosome 6, that for ET-2 on chromosome 1, and the gene for ET-3 on chromosome 20 [5].

Figure 1.

Biosynthesis and amino acid sequence and structure of endothelin-1, endothelin-2, and endothelin-3 and related sarafotoxins. ET-2 and ET-3 differ from ET-1 by two and five amino acids, respectively, while sarafotoxin differs by seven amino acids.

Table 2.

Sites of endothelin-1 synthesis in the lung

| Airway |

| Epithelium |

| Epithelial cells |

| Clara cells |

| Neuroendocrine cells |

| Smooth muscle cells |

| Parenchyma |

| Clara cells |

| Macrophages |

| Endothelial cells |

| Pulmonary tumors |

| Adenocarcinomas |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Small cell carcinoma? |

| Carcinoid tumors |

| Vasculature |

| Endothelial cells |

| Platelets |

| Smooth muscle |

All three endothelins are synthesized as preprohormones and post-translationally processed to active peptides. ET-1 processing has been best characterized and begins with the 212 amino acid peptide (preproET-1), which is then proteolytically cleaved by endopeptidases to big ET-1 (proET-1). The 39 amino acid proET-1 has 1% of the biologic activity of ET-1, and is cleaved by the metalloendoprotease endothelin converting enzyme (ECE), resulting in the 21 amino acid protein with potent biologic functions [6,7] (Fig. 1). ECE is found in many cell types in the lung including endothelium, epithelium and alveolar macrophages [8]. ET-1 is not stored in the cell [9,10], but is processed and transported through the cell in vesicles, resulting in directional secretion (80%) of ET-1 toward the interstitium and smooth muscle and away from the luminal surface of the airway or vessel [11,12,13]. Directional secretion allows ET-1 to act in a paracrine or autocrine manner whereas secretion into the circulation allows ET-1 to act as a hormone.

There are currently two distinct human endothelin receptors known, endothelin A (ETA) and endothelin B (ETB) receptors, which are members of the seven transmembrane, G protein-coupled rhodopsin superfamily [14,15]. The ETA and ETB receptor genes are located on chromosomes 4 and 13, respectively. ETA has a higher affinity for ET-1 and ET-2 than ET-3, but all three have equal affinity for ETB receptors. A third receptor subtype (endothelin C) with high affinity for ET-3 has been isolated and cloned from Xenopus laevis [16]. ETA receptors in normal lung are found in greatest abundance on vascular and airway smooth muscle, whereas ETB receptors are most often found on the endothelium. Clearance of ET-1 from the circulation is mediated by the ETB receptor primarily in the lung, but also in the kidney and liver [17].

Activation of both ETA and ETB receptors on smooth muscle cells leads to vasoconstriction whereas ETB receptor activation leads to bronchoconstriction. Activation of ETB receptors located on endothelial cells leads to vasodilation by increasing nitric oxide (NO) production. The mitogenic and inflammatory modulator functions of ET-1 are primarily mediated by ETA receptor activity. Binding of the ligand to its receptor results in coupling of cell-specific G proteins that activate or inhibit adenylate cyclase, stimulate phosphatidyl-inositol-specific phosholipase, open voltage gated calcium and potassium channels, and so on. The varied effects of ET-1 receptor activation thus depend on the G protein and signal transduction pathways active in the cell of interest [18]. A growing number of receptor antagonists exist with variable selectivity for one or both receptor subtypes.

Regulation of ET-1 is at the level of transcription, with stimuli including shear stress, hypoxia, cytokines (IL-2, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-β, etc), lipopolysaccharides, and many growth factors (transforming growth factor β, platelet-derived growth factor, epidermal growth factor, etc) inducing transcription of ET-1 mRNA and secretion of protein [18]. ET-1 acting in an autocrine fashion may also increase ET-1 expression [19]. ET-1 expression is decreased by NO [20]. Some stimuli may additionally enhance preproET-1 mRNA stability, leading to increased and sustained ET-1 expression. The number of ETA and ETB receptors is also cell specific and regulated by a variety of growth factors [18]. Because ET-1 and receptor expression is influenced by many diverse physical and biochemical mechanisms, the role of ET-1 in pathologic states has been difficult to define, and these are addressed in subsequent parts of this article.

Airway diseases

In the airway, ET-1 is localized primarily to the bronchial smooth muscle with low expression in the epithelium. Cellular subsets of the epithelium that secrete ET-1 include mucous cells, serous cells, and Clara cells [21]. ET binding sites are found on bronchial smooth muscle, alveolar septae, endothelial cells, and parasympathetic ganglia [22,23]. ET-1 expression in the airways, as previously noted, is regulated by inflammatory mediators. Eosinophilic airway inflammation, as may be seen in severe asthma, is associated with increased ET-1 levels in the lung [24]. ET-1 secretion may also act in an autocrine or paracrine fashion, via the ETA receptor, leading to increased transepithelial potential difference and ciliary beat frequency, and to exerting mitogenic effects on airway epithelium and smooth muscle cells [25,26,27,28].

All three endothelins cause bronchoconstriction in intact airways, with ET-1 being the most potent. Denuded bronchi constrict equally to all three endothelins, suggesting considerable modulation of ET-1 effects by the epithelium [29]. The vast majority of ET-1 binding sites on bronchial smooth muscle are ETB receptors, and bronchoconstriction in human bronchi is not inhibited by ETA antagonists but augmented by ETB receptor agonists [30,31,32]. Since cultured airway epithelium secretes equal amounts of ET-1 and ET-3, which have equivalent affinity for the ETB receptor, bronchoconstriction could be mediated by both endothelins [33].

While ET-1 stimulates release of multiple cytokines important in airway inflammation, it does not enhance secretion of histamine or leukotrienes. ET-1 does increase prostaglandin release [32]. Inhibition of cyclo-oxygenase, however, has no effect on bronchoconstriction suggesting that, despite the release of multiple mediators, ET-1 mediated bronchoconstriction is a direct effect of activation of the ETB receptor [32]. ETA mediated bronchoconstriction may also be important following ETB receptor desensitization or denudation of the airway epithelium, as may occur during airway inflammation and during the late, sustained airway response to inhaled antigens [31,34,35]. Interestingly, heterozygous ET-1 knockout mice, with a 50% reduction in ET-1 peptide, have airway hyperresponsiveness but not remodeling, suggesting the decrease in ET-1 modulates bronchoconstriction activity by a functional mechanism, possibly by decreasing basal NO production [36,37].

Asthma is also an inflammatory airway disease characterized by bronchoconstriction and hyperreactivity with influx of inflammatory cells, mucus production, edema, and airway thickening. ET-1 may have important roles in each of these processes. While ET-1 causes immediate bronchoconstriction [38], it also increases bronchial reactivity to inhaled antigens [35] as well as influx of inflammatory cells [39,40], increased cytokine production [40], airway edema [41], and airway remodeling [28,42,43]. Airway inflammation also leads to increased ET-1 synthesis, possibly perpetuating the inflammation and bronchoconstriction [44]. ET-1 release from cultured peripheral mononuclear and bronchial epithelial cells from asthmatics is also increased [45,46]. Inhibition of ETA or combined ETA and ETB receptors additionally leads to decreased airway inflammation in antigen-challenged animals, suggesting that the proinflammatory effects of ET-1 in the airway are mediated by ETA receptors [39,47].

Children with asthma have increased circulating levels of ET-1 [48]. Adult asthmatics have normal levels between attacks but, during acute attacks, have elevated serum ET-1 levels that correlate inversely with airflow measurements and decrease with treatment [49]. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) ET-1 in asthmatics is similarly increased to concentrations that cause bronchoconstriction and inversely correlates with forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) [29,50,51]. As in cultured epithelial cells, ET-1 and ET-3 are found in equal amounts in BAL fluid from asthmatics [33,52]. There is also a relative increase in ETB versus ETA receptor expression in asthmatic patients, which may contribute to increased bronchoconstriction [53]. Not all asthmatics, however, have increased ET-1 as patients with nocturnal asthma have decreased BAL ET-1 levels [54]. Treatment of acute asthma exacerbations with steroids, beta-adrenergic agonists or phosphodiesterase inhibitors resulted in decreased BAL ET-1 [52,55]. Immunostaining and in situ hybridization for ET-1 in biopsy specimens from asthmatics have shown an increase in ET-1 in the bronchial epithelium that correlates with asthma symptoms [46,56].

Cigarette smoking leads to increased circulating ET-1 [57] but patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, in the absence of pulmonary hypertension and hypoxemia, do not have increased plasma ET-1 [58,59,60]. Increases in urinary ET-1 instead correlate with decreases in oxygenation, possibly through hypoxic release of ET-1 from the kidney [61,62]. Smokers also have impaired ET-1 mediated vasodilation that correlates with bronchial hyperresponsiveness and may contribute to pulmonary hypertension [63,64].

ET-1 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of bronchiectasis by its ability to promote neutrophil chemotaxis, adherence, and activation [65,66,67,68,69]. Sputum ET-1 levels are increased in patients with cystic fibrosis [59], and sputum ET-1 correlated with Pseduomonas infection in noncystic fibrosis related bronchiectasis [70].

ET-1 has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis obliterans (BO), which is characterized by injury to small conducting airways resulting in formation of proliferative, collagen rich tissue obliterating airway architecture. BO is the leading cause of late mortality from lung transplantation, and ET-1 is increased in lung allografts [71]. The pro-inflammatory and mitogenic properties of ET-1 in the airways has led to speculation that ET-1 may be involved in formation of the lesion [28]. This is further supported by the increase in BAL ET-1 in lung allografts [72,73]. The in vivo gene transfer of ET-1 to the airway epithelium using the hemagglutinating virus of Japan in rats recently resulted in pathologic changes in the distal airways identical to those seen in human BO specimens [74]. These changes were not due to nonspecific effects of the hemagglutinating virus of Japan itself, but could be attributed to the presence of the ET-1 gene, which was localized to the airway epithelium, hyperplastic lesions, and alveolar cells.

Pulmonary vascular disease

Pulmonary hypertension is a rare and progressive disease characterized by increases in normally low pulmonary vascular tone, pulmonary vascular remodeling, and progressive right heart failure. ET-1 has been implicated as a mediator in the changes seen in pulmonary hypertension. In the pulmonary vasculature, ET-1 is found primarily in endothelial cells and to a lesser extent in the vascular smooth muscle cells. The endothelium secretes ET-1 primarily to the basolateral surface of the cell. ET-1 secretion may be increased by a variety of stimuli including cytokines, catecholamines, and physical forces such as shear stress, and decreased by NO, prostaglandins, and oxidant stress [20,75,76,77,78]. Hypoxia has been reported to increase, have no effect, or decrease ET-1 release from endothelial cells [79,80,81,82,83].

Activation of the receptors for ET-1 in the pulmonary vasculature leads to both vasodilation and vasoconstriction, and depends on both cell type and receptor. In the whole lung, ETA receptors are the most abundant and are localized to the medial layer of the arteries, decreasing in intensity in the peripheral circulation [84,85]. ETB receptors are also found in the media of the pulmonary vessels, increasing in intensity in the distal circulation, while intimal ETB receptors are localized in the larger elastic arteries [85]. This distribution of receptors has important implications in understanding ET-1 regulation of vascular tone. Vascular ET-1 receptors may be increased by several factors including angiotensin and hypoxia [80,85,86,87].

ET-1 can act as both a vasodilator and vasoconstrictor in the pulmonary circulation. Generation of NO or opening of ATP-sensitive potassium channels leading to hyperpolarization results in vasodilation mediated by ETB receptors on pulmonary endothelium [88,89]. In hypertensive, chronically hypoxic lungs with increased ETB receptor expression, augmented vasodilation is due to increased ETB mediated NO release that is inhibited by hypoxic ventilation, while inhibition of NO synthesis leads to increased ET-1 mediated vasoconstriction [85,90,91,92]. Both ETA and ETB receptors, conversely, acting on vascular smooth muscle, mediate ET-1 induced vasoconstriction. In the normal lung, ET-1 causes vasoconstriction primarily by activation of the ETA receptors in the large, conducting vessels of the lung [93,94]. In the smaller, resistance vessels of the lung, ETB receptors in the media predominate and are responsible for the ET-1 induced vasoconstriction [93]. Interestingly, preconstriction of the pulmonary circulation resulted in a shift from primarily ETA mediated to ETB mediated vasoconstriction [94].

The overall effect of ET-1 on vascular tone depends on both the dose and on the pre-existing tone in the lung. ET-1 administration during acute hypoxic vasoconstriction will result in transient pulmonary vasodilation [89]. This effect is dose dependent, with lower doses leading to vasodilation while higher or repetitive doses cause vasoconstriction following an initial, brief vasodilation [89]. The role of ET-1 in the acute hypoxic vasoconstriction in the lung is not certain. ETA receptor antagonism attenuates hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in several species [95], and ET-1 may be implicated in the mechanism of acute hypoxic response by inhibition of K-ATP channels [96].

Several lines of evidence have suggested the importance of ET-1 in chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. ET-1 is increased in plasma and lungs of rats following exposure to hypoxia [80,97]. Treatment with either ETA or combined ETA and ETB receptor antagonists additionally attenuates the development of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension [98,99]. ET-1 has also been implicated in the vascular remodeling associated with chronic hypoxia through its mitogenic effects on vascular smooth muscle cells [98,100].

ET-1 has also been implicated in other animal models of pulmonary hypertension. ET-1 is increased in fawn hooded rats that develop severe pulmonary hypertension when raised under conditions of mild hypoxia and in monocrotaline treated rats [101,102]. The increase in ET-1 in both of these forms of pulmonary hypertension may be contributing to increases in vascular tone as well as in vascular remodeling [103,104,105,106,114]. Interestingly, transgenic mice overexpressing the human preproET-1 gene, with modestly increased lung ET-1 levels (35-50%), do not develop pulmonary hypertension under normoxic conditions or an exaggerated response to chronic hypoxia [107].

Human pulmonary hypertension is classified as primary, or unexplained, or secondary to other cardiopulmonary diseases or connective tissue diseases (ie scleroderma). Hallmarks of the disease include progressive increases in pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary vascular remodeling, with thickening of the medial layer small pulmonary arterioles and formation of the complex plexiform lesion [108]. Circulating ET-1 is increased in humans with pulmonary hypertension, either primary or due to other cardiopulmonary disease [109]. Levels are highest in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Since the lung is the major source for clearance of ET-1 from the circulation, increased arterio-venous ratios as seen in primary pulmonary hypertension suggest either decreased clearance or increased production in the lung [17,109]. ET-1 is also increased in lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension, with the greatest increase seen in the small resistance arteries and the plexiform lesions [110], and may correlate with pulmonary vascular resistance [111]. Interestingly, treatment with continuous infusion of prostacyclin resulted in clinical improvement and a decrease in the arterio-venous ratio of ET-1 [112], possibly by decreasing ET-1 synthesis from endothelial cells [76]. Studies using ET-1 receptor antagonists in the treatment of primary pulmonary hypertension are underway and may offer hope to patients with this disease by inhibiting this pluripotent peptide's effects on vascular tone and remodeling.

Lung transplantation and rejection

Several lines of evidence suggest the importance of ET-1 in lung allograft survival and rejection. The peptide has been implicated as an important factor in ischemia-reperfusion injury at the time of transplant as well as in acute and chronic rejection of the allograft.

Circulating ET-1 is increased in humans undergoing lung transplant immediately following perfusion of the allograft. Plasma ET-1 increased threefold within minutes, remained high for 12 hours following transplantation, and declined to near normal levels within 24 hours [113]. This increase in ET-1 correlated with the increase in pulmonary vascular resistance occurring about 6 hours post-transplantation, suggesting that the release of ET-1 in the circulation may have mediated this event. ET-1 in BAL fluid from recipients of lung allografts is similarly increased several fold and remains elevated up to 2 years post-transplant [72,73]. In recipients of single lung transplants, ET-1 was increased 10-fold in BAL fluid from the transplanted lung compared with the native lung, suggesting that the increase in ET-1 was due to the graft and not the underlying disease requiring transplant [72]. ET-1 in BAL fluid did not, however, correlate with episodes of infection or rejection.

The cellular source of ET-1 in lung allografts is unknown. The expression of ET-1 in nontransplanted human lungs is low and found primarily in the vascular endothelium [114]. Transbronchial biopsy specimens obtained either for surveillance or for clinical suspicion of infection or rejection following transplantation revealed the presence of ET-1 in the airway epithelium and in alveolar macrophages [115]. ET-1 was occasionally seen in lymphocytes but not in the endothelium or pneumocytes. ET-1 localization was no different in surveillance specimens compared with infected or rejecting lungs, or changed over time from transplantation. This study suggests that the source of the increased BAL ET-1 in transplanted lungs is due to the increased number of alveolar inflammatory cells and de novo expression in the airway epithelium. The biologic importance of the ET-1 from inflammatory cells is supported by the observation that peripheral mononuclear cells from dogs with mild to moderate lung allograft rejection cause vasoconstriction in pulmonary arterial rings, which is attenuated by the ETA blocker BQ123 [116].

Analysis of ET-1 binding activity in failed transplanted human lungs suggested that ET-1 binding activity was not different compared with normal lung in the lung parenchyma, bronchial smooth muscle, or perivascular infiltrates. ET-1 binding was, however, decreased in small muscular arteries (pulmonary arteries and bronchial arteries) in the failed transplants, suggesting a role for ET-1 in impaired vasoregulation of transplanted lungs [117].

Ischemia-reperfusion injury is the leading cause of early post-operative graft failure and death. In its severest manifestation, increased pulmonary vascular resistance, hypoxia, and pulmonary edema lead to cor pulmonale and death [118]. ET-1 has been implicated as a mediator of these events. The increase in pulmonary vascular resistance observed in human recipients of lung allografts follows an increase in circulating ET-1 and falls with decreases in circulating ET-1 [113]. A similar pattern is seen in dogs subjected to allotransplantation [119]. Conscious dogs with left pulmonary allografts demonstrate an increase in both resting pulmonary perfusion pressure and acute pulmonary vasoconstrictor response to hypoxia [120]. Administration of ETA selective or combined ETA and ETB receptor blockers did not change the resting tone. ETB receptor mediated hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction appeared, however, to be increased in allograft recipients. In another study, administration of a mixed ETA and ETB receptor antagonist (SB209670) to dogs before reperfusion of the allograft resulted in a marked increase in oxygenation, decreases in pulmonary arterial pressures and improved survival compared with control animals [121]. In a model of ischemia reperfusion, inhibitors of ECE additionally attenuated the increase in circulating ET-1 and the severity of lung injury [122]. ET-1 receptor antagonists did not, however, completely eliminate the ischemia-reperfusion injury, suggesting that changes in other vasoactive mediators, such as an increase in thromboxane, a decrease in prostaglandins, or a decrease in NO, may also contribute to the increased pulmonary vascular resistance. Administration of NO donor (FK409) to both donor and recipient dogs before lung transplantation reduced pulmonary arterial pressure, lung edema, and inflammation, and improved survival. This suggests that reductions in NO following transplantation may be partly responsible for early graft failure [123]. Treatment with NO donor was also associated with a decrease in plasma ET-1 levels.

Acute rejection is manifested by diffuse infiltrates, hypoxia, and airflow limitation, and may lead to respiratory insufficiency and death. BAL ET-1 was increased in dogs during episodes of acute rejection that decreased with immunosuppressive treatment [124]. Acute episodes of rejection in humans, however, are not associated with further increases in BAL ET-1 [72]. Chronic rejection of allografts, manifested as BO, is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in long-term lung transplant survivors [71]. The etiology of BO following transplant is unclear but may be related to repeated episodes of acute rejection, chronic low-grade rejection, or organizing pneumonia [125]. As discussed earlier, a chronic increase in ET-1, as seen in lung allografts, may contribute to bronchospasm and proliferative bronchiolitis obliterans due to the bronchoconstrictor and smooth muscle mitogenic effects of ET-1 [28,126]. This is further supported by the increase of BAL ET-1 in the transplanted lung, which is susceptible to BO, but not the native lung in recipients of single lung transplants [72].

Pulmonary malignancies

The mitogenic effects of ET-1 may play a role in the development of pulmonary malignancy as well as metastasis to the lung. Many human tumor cell lines, including prostate, breast, gastric, ovary, colon, etc, produce ET-1. The importance of the ET-1 may lie in its mitogenic effects on tumor growth and survival. This has been suggested by blockade of ETA receptors resulting in a decrease in mitogenic effects of ET-1 in a prostate cancer and colorectal cell lines [127,128]. ET-1 receptors in tumor cells may also be altered with increases in the ETA receptor and downregulation of ETB receptors [129]. Other tumors may have an increase in ETB receptors, however, and blockade of ETB results in a decrease in tumor growth [130,131]. Tumor cells may, as a result of this altered balance, lose the ability to respond to regulatory signals from their environment. ET-1 may additionally protect against Fas-ligand mediated apoptosis [132].

ET-1 has been detected using immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization in pulmonary adenocarcinomas and squamous cell tumors and, to a lesser extent, small cell and carcinoid tumors [133]. In situ hybridization also demonstrated a similar pattern of ET-1 mRNA expression in non-neuroendocrine tumors. ET-1 receptors have also been found in a variety of pulmonary tumor cell lines. ETA receptors were found in small cell tumors, adenocarcinomas and large cell tumors, while ETB receptors were expressed primarily in adenocarcinomas and small cell tumors [134]. ECE, which converts big ET-1 to ET-1, the committed step in ET-1 biosynthesis, was also found in human lung tumors but not in adjacent normal lung [135]. These findings, combined with the presence of ET-1 in lung tumors, suggest a possible autocrine loop that sustains and supports the growth of lung tumors. A recent study, however, suggested that, while ETA and ECE-1 were detectable in lung tumors, these genes were downregulated compared with normal bronchial epithelial cell lines [136]. It was proposed that the role of ET-1 in lung tumors is not that of an autocrine factor, but that of a paracrine growth factor to the stroma and vasculature surrounding the tumor allowing angiogenesis.

Tumor angiogenesis is necessary for continued growth of the tumor beyond the limits of oxygen diffusion. The growth of vessels into the tumor is also important to metastatic potential of the tumor. ET-1 may play an important role in angiogenesis and tumor growth and survival through induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and sprouting of new vessels into the tumor and surrounding tissue [137,138]. ET-1 binding activity was found in blood vessels and vascular stroma surrounding lung tumors at the time of resection, most markedly surrounding squamous cell tumors [139]. ET-1 production may be further augmented by the hypoxic environment found within large solid tumors [140]. Since metastasis is dependent on neovascularization, ET-1 may also be an important mediator of this phenomenon. ET-1 receptor antagonists may have a useful role in the treatment of neoplastic disease by inhibiting growth as well as metastatic potential of human tumors.

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Experimental lung injury of many different types results in increased circulating ET-1, BAL ET-1, and lung tissue ET-1 [18]. ET-1 levels in humans are also increased in sepsis, burns, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute lung injury, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [141,142,143,144,145,146,147]. ET-1 increases also correlate with a poorer outcome with multiple organ failure, increased pulmonary arterial pressure, increased airway pressure and decreased PiO2/FiO2, while clinical improvement correlates with decreased ET-1 levels [144,145,147]. The arterio-venous ratio for ET-1 is increased in patients with ARDS but it is not clear whether this is due to increased secretion of ET-1 in the lungs or decreased clearance [142,144]. In patients who succumbed to ARDS, there was also a marked increase in tissue ET-1 immunostaining in vascular endothelium, alveolar macrophages, smooth muscle, and airway epithelium compared with lungs of patients who died without ARDS. Interestingly, these same patients also had a decrease in immunostaining for both endothelial nitric oxide synthase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in the lung [148].

ARDS is also characterized by the presence of inflammatory cells in the lung. Since ET-1 may act as an immune modulator, an increase in ET-1 may contribute to lung injury by inducing expression of cytokines including tumor necrosis factor and IL-6 and IL-8 [149]. These cytokines may in turn stimulate the production of many inflammatory mediators, leading to lung injury. ET-1 additionally activated neutrophils, and increased neutrophil migration and trapping in the lung [65,66,67,68,69].

Another hallmark of ARDS is disruption and dysfunction of the pulmonary vascular endothelium leading to accumulation of lung water. The role of endothelin in formation of pulmonary edema is uncertain. Infusion of ET-1 raises pulmonary vascular pressure, but it is uncertain whether ET-1 by itself increased pulmonary protein or fluid transport in the lung [150,151,152]. ET-1 may rather be acting synergistically with other mediators to lead to pulmonary edema [153,154].

Pulmonary fibrosis

Pulmonary fibrosis is the final outcome for a variety of injurious processes involving the lung parenchyma. The final common pathway in response to injury to the alveolar wall involves recruitment of inflammatory cells, release of inflammatory mediators, and resolution. The reparative phase occasionally becomes disordered, resulting in progressive fibrosis.

ET-1 in the lung may be important in the initial events in lung injury by activating neutrophils to aggregate and release elastase and oxygen radicals, increasing neutrophil adherence, activating mast cells, and inducing cytokine production from monocytes [65,66,67,68,69,149,155]. Among the many cytokines induced by ET-1 that are important in mediating pulmonary fibrosis are transforming growth factor-β and tumor necrosis factor α [156,157]. ET-1 is also profibrotic by stimulating fibroblast replication, migration, contraction, and collagen synthesis and secretion while decreasing collagen degradation [158,159,160,161,162]. ET-1 additionally enhances the conversion of fibroblasts into contractile myelofibroblasts [43,163]. ET-1 also increases fibronectin production by bronchial epithelial cells [164]. Finally, ET-1 has mitogenic effects on vascular and airway smooth muscle [126,28]. ET-1 may thus play an important role in the initial injury and eventual fibrotic reparative process of many inflammatory events in the lung.

Several lines of evidence regarding the importance of ET-1 in pulmonary fibrosis are available. Plasma and BAL ET-1 levels are increased in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [50,165]. Lung biopsies from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have additionally increased ET-1 immunostaining in airway epithelial cells and type II pneumocytes, which correlates with disease activity [166]. Scleroderma is commonly associated with pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary fibrosis. Plasma and BAL ET-1 is increased in these patients [160,167,168], but it is unclear whether the presence of either pulmonary hypertension or pulmonary fibrosis increases these levels further [167]. BAL fluid from patients with scleroderma increased proliferation of cultured lung fibroblasts, which was inhibited by ETA receptor antagonist. This suggests that the ET-1 in the airspace may be contributing significantly to the fibrotic response [160]. An increase in ET-1 binding has also been reported in lung tissue from patients with scleroderma associated pulmonary fibrosis [169]. Pulmonary inflammatory cells also appear to be primed for ET-1 production because cultured alveolar macrophages from patients with scleroderma and lung involvement secrete increased amounts of ET-1 in response to stimulation with lipopolysaccharide [170]. These observations collectively suggest that augmented ET-1 release may contribute to and perpetuate the inflammatory process.

Bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in animals is associated with increased ET-1 expression in alveolar macrophages and epithelium [171]. The increase in ET-1 proceeds the development of pulmonary fibrosis. The use of ET-1 receptor antagonists has produced mixed results in limiting the development of bleomycin-induced fibrosis. A decrease in fibroblast replication and secretion of extracellular matrix proteins in vitro but not a decrease in lung collagen content in vivo has been shown using ETA or combined ETA and ETB receptor antagonists after bleomycin [172]. Another group did, however, observe a decrease in fibrotic area in lungs of rats following bleomycin that were treated with a mixed ETA and ETB receptor antagonist [173].

While ET-1 seems to correlate with pulmonary fibrosis, it remains uncertain whether the increase in ET-1 is a cause or consequence of the lung disease. Pulmonary fibrosis was recently reported in mice that constitutively overexpress human ET-1 [107]. These mice were known to develop progressive nephrosclerosis in the absence of systemic hypertension [174]. The transgene was localized throughout the lung, with the strongest expression in the bronchial wall. In the lung, the mice developed age-dependent accumulation of collagen and accumulation of CD4+ lymphocytes in the perivascular space. This observation suggests that an increase in lung ET-1 alone may play a causative role in the development of pulmonary fibrosis [107,175].

Conclusion

Since its discovery 12 years ago, much evidence has accumulated regarding the biologic activity and potential role of ET-1 in a variety of diseases of the respiratory track. As compelling as much of this evidence is, the causal relationship between ET-1 activity and disease is not complete. The increasing use of ECE and endothelin receptor antagonists in experimental and human respiratory disorders will help to clarify the role of this pluripotent peptide in health and disease.

Abbreviations

ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage; BO = bronchiolitis obliterans; ECE = endothelin converting enzyme; ETA = endothelin A; ETB = endothelin B; ET-1 = endothelin-1; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1s; NO = nitric oxide.

References

- Hickey KA, Rubani GB, Paul RJ, Highsmith RF. Characterization of a coronary vasoconstrictor produced by cultured endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:C550–C556. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1985.248.5.C550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie MN, Owasoyo JO, McMurtry IF, O'Brien RF. Sustained coronary vasoconstriction provoked by a peptidergic substance released from endothelial cells in culture. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;236:339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien RF, Robbing RJ, McMurtry IF. Endothelial cells in culture produce a vasoconstrictor substance. J Cell Physiol. 1987;132:263–270. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041320210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 1999;332:411–415. doi: 10.1038/332411a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arinami T, Ishikawa M, Inoue A, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Yoshida MC, Hamaguchi H. Chromosomal assignments of the human endothelin family genes: the endothelin-1 gene (EDN-1) to 6p23-p24, the endothelin-2 gene (EDN-2) to 1p34, and the endothelin-3 gene (EDN-3) to 20q13.2-q13.3. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:990–996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Mitsui Y, Kobayashi M, Masaki T. The human preproendothelin-1 gene: complete nucleotide sequence and regulation of expression. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14954–14959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Kasuya Y, Sawamura T, Shinmi O, Sugita Y, Yanagisawa M, Goto K, Masaki T. Conversion of bug endothelin-1 to 21-residue endothelin-1 is necessary for expression of full vasoconstrictor activity: structure-activity relationships of big endothelin-1. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1989;13 (suppl 5):S5–S7. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198900135-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battistini B, Dussault P. Biosynthesis, distribution and metabolism of endothelins in the pulmonary system. Pulmon Pharmacol Ther. 1998;11:79–88. doi: 10.1006/pupt.1998.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S, Naruse M, Naruse K, Demura H, Uemura H. Immunocytochemical localization of endothelin in cultured bovine endothelial cells. Histochemistry. 1990;94:475–477. doi: 10.1007/BF00272609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison VJ, Barnes K, Turner AJ, Wood E, Corder R, Vane JR. Identification of endothelin-1 and big endothelin-1 in secretory vesicles isolated from bovine aortic endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6344–6348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison VJ, Corder R, Anggard EE, Vane JR. Evidence for vesicles that transport endothelin-1 in bovine aortic endothelial cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1993;22 (suppl 2):S57–S60. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199322008-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner OF, Christ G, Wojta J, Vierhapper H, Parzer S, Nowotny PJ, Schneider B, Waldhausl W, Binder BR. Polar secretion of endothelin-1 by cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:16066–16068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi Y, Uchida Y, Endo T, Ninomiya H, Nomura A, Sakamoto T, Goto Y, Haraoka S, Shimokama T, Watanabe T, Hasegawa S. The induction of cell differentiation and polarity of tracheal epithelium cultured on amniotic membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:302–309. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippton HL, Hauth TA, Cohen GA, Hyman AL. Functional evidence for different endothelin receptors in the lung. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:38–48. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis J, Stewart DJ, Cernacek P, Gosselin G. Human pulmonary circulation is an important site for both clearance and production of endothelin-1. Circulation. 1996;94:1578–1584. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael JR, Markewitz BA. Endothelins and the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:555–581. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.3.8810589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Homma T, Matsuda Y, Kon V. Endothelin receptor subtype B mediates auto-induction of endothelin-1 in rat mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6997–7003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourembanas S, McQuillan LP, Leung GK, Faller DV. Nitric oxide regulates the expression of vasoconstrictors and growth factors by vascular endothelium under both normoxia and hypoxia. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:99–104. doi: 10.1172/JCI116604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozengurt N, Springall DR, Polak JM. Localization of endothelin-like immunoreactivity in airway epithelium of rats and mice. J Pathol. 1990;160:5–8. doi: 10.1002/path.1711600104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power RF, Wharton J, Zhao Y, Bloom SR, Polak JM. Autoradiographic localization of endothelin-1 binding sites in the cardiovascular and respiratory system. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1989;13 (suppl 5):S50–S56. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198900135-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry PT. Endothelin receptor distribution and function in the airways. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:162–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsnes F, Skjonsberg SK, Lyberg T, Christensen G. Endothelin-1 production is associated with eosinophilic rather than neutrophilic airway inflammation. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:743–750. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00.15474300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, Shimura S, Ishihara H, Nagaki M, Sasaki H, Takishima T. Endothein-1 stimulates chloride secretion across canine tracheal epithelium. Respiration. 1992;59:145–150. doi: 10.1159/000196045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki J, Kanemura T, Sakai N, Isono K, Kobayashi K, Takizawa T. Endothelin stimulates cililary beat frequency and chloride secretion in canine cultured tracheal epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4:426–431. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.5.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murlas CG, Gulati A, Singh G, Najmabadi F. Endothelin-1 stimulates proliferation of normal airway epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:953–959. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassberg MK, Ergul A, Wanner A, Puett D. Endothelin-1 promotes mitogenesis in airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;10:316–321. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.10.3.7509612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candenas M-L, Naline E, Sarria B, Advenier C. Effect of epithelium removal and enkephalin inhibition of the bronchoconstrictor response of three endothelins and the human isolated bronchus. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;210:291–297. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DWP, Luttmann MA, Hubbard WC, Undem BJ. Endothelin receptor subtypes in human and guinea pig pulmonary tissues. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:1175–1183. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldie RG, Heny PJ, Knott PG, Self GJ, Luttmann MA, Hay DWP. Endothelin-1 receptor density, distribution and function in human isolated asthmatic airway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1653–1658. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.5.7582310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DWP, Hubbard WC, Undem BJ. Endothelin-induced contraction and mediator release in human bronchus. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:392–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blade PN, Ghabei GH, Takahashi K, Bertheton-Watt D, Kransz T, Pollen CT, Bloom SR. Formation of endothelin by cultured airway epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1989;255:129–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen LA, Heino M, Laitinen A, Kava T, Haahtela T. Damage of the airway epithelium and bronchial reactivity in patients with asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;131:599–606. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.131.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K, Ishikawa K, Yano M, Ahmed A, Cortes A, Abraham WM. Endothelin-1 contributes to antigen-induced airways hyperresponsiveness. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:700–705. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.3.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T, Kurihara H, Kurihara Y, Aoki-Nagase T, Nagai R, Ouchi Y. Disruption of ET-1 gene enhances pulmonary responses to methacholine via a functional mechanism in knockout mice. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:2020–2024. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T, Kurihara H, Kurihara Y, Aoki T, Fukuchi Y, Yazaki Y, Ouchi Y. Airway hyperresponsiveness in mutant mice deficient in endothelin-1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:560–564. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.9706009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers GW, Little SA, Patel KR, Thomson NC. Endothelin-1-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:382–388. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9702066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsnes F, Skjonsberg OH, Tonnessen T, Naess O, Lyberg T, Christensen G. Endothelin production and effects of endothelin antagonism during experimental airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1404–1412. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.4.9105086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers GW, MacLeod KJ, Thomson LJ, Little SA, Patel KR, McSharry C, Thomson NC. Sputum cellular responses to inhaled endothelin-1 in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:1526–1531. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirois MG, Filep JG, Rousseau A, Farmer A, Plante GE, Sirois P. Endothelin-1 enhances vascular permeability in conscious rats: role of thromboxane A2. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;214:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90108-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldie RG. Potential role of the endothelins in airway remodeling in asthma. Pulmon Pharmacol Ther. 1999;12:79–80. doi: 10.1006/pupt.1999.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Stacey MA, Bellini A, Marini M, Mattoli S. Endothelin-1 induces bronchial myofibroblast differentiation. Peptides. 1997;18:1449–1451. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(97)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsnes F, Christensen G, Lyberg T, Sejersted OM, Skjonsberg OH. Increased synthesis and release of endothelin-1 during the initial phase of airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1600–1606. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9707082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittori E, Marini M, Fasoli A, DeFranchis R, Mattoli S. Increased expression of endothelin in bronchial epithelial cells of asthamtic patients and effect of corticosteroids. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1320–1325. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_1.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackerman V, Carpi V, Bellini A, Vassalli G, Marini M, Mattoli S. Constitutive expression of endothelin in bronchial and epithelial cells of patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic asthma and modulation by histamine and interleukin-1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:618–627. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70260-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujitani Y, Trifileff A, Tsuyuki S, Coyle AJ, Bertrand C. Endothelin receptor antagonists inhibit antigen induced lung inflammation in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1890–1894. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.6.9196091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W-Y, Yu J, Wang J-Y. Decreased production of endothlin-1 in asthmatic children after immunotherapy. J Asthma. 1995;32:29–35. doi: 10.3109/02770909509089497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T, Kojima T, Ono A, Unishi G, Yoshijima S, Kameda-Hayashi N, Yamamoto C, Hirata Y, Kobayashi Y. Circulating endothelin-1 levels in patients with bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy. 1994;73:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofia M, Mormile M, Faraone S, Alifano M, Zofra S, Romano L, Carratu V. Increased endothelin-like immunoreactive material on bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with bronchial asthma and patients with interstitial lung disease. Respiration. 1993;60:89–95. doi: 10.1159/000196180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redington AE, Springall DR, Ghatei MA, Lau LCK, Bloom SR, Holgate ST, Polak JM, Howarth PH. Endothelin in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and its relation to airflow obstruction in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1034–1039. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.4.7697227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattoli S, Soloperto M, Marini M, Fasoli A. Levels of endothelin in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with symptomatic asthma and reversible airflow obstruction. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;88:376–384. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller S, Uddman R, Granstrom B, Edvinsson L. Altered ration of ETa and ETb receptor mRNA in bronchial biopsies from patients with asthma and chronic airway obstruction. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;365:R1–R3. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft M, Beam WR, Wenzel SE, Zamora MR, O'Brien RF, Martin RJ. Blood and bronchoalveolar lavage endothelin-1 levels in nocturnal asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:947–952. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.4.8143060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T, Kojima T, Ono A, Unishi G, Yoshijima S, Kameda-Hayashi N, Yamamoto C, Hirata Y, Kobayashi Y. Circulating endothelin-1 levels in patients with bronchial asthma. Ann Allergy. 1994;73:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springall DR, Howarth PH, Counihan H, Djukanovic R, Holgate ST, Polak JM. Endothelin immunoreactivity of airway epithelium in asthmatic patients. Lancet. 1991;337:697–701. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90279-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haak T, Jungman E, Raab C, Usadel KH. Elevated endothelin-1 levels after cigarette smoking. Metabolism. 1994;43:267–269. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(94)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii T, Otsuka T, Tanaka S, Kanazawa Y, Hirata K, Kohno M, Kurihara N, Yoshikawa J. Plasma endothelin-1 levels in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: relationship with naturitic peptide. Respiration. 1999;66:212–219. doi: 10.1159/000029380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers GW, Macleod KJ, Sriram S, Thomson LJ, McSharry C, Stack BHR, Thomson NC. Sputum endothelin-1 is increased in active fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1288–1292. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13f12.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celik G, Karabiyikoglu G. Local and peripheral plasma endothelin-1 in pulmonary hypertension secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 1998;65:289–294. doi: 10.1159/000029278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofia M, Mormile M, Faraone S, Carratu P, Alifano M, Di Benedetto G, Carruth L. Increased 24 hour endothelin-1 urinary excretion in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 1994;61:263–268. doi: 10.1159/000196349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AC, Jowett TP, Firth JD, Burton S, Karet FE, Fine LG. An endothelin-1 mediated autocrine growth loop involved in human renal tubular regeneration. Kidney Int. 1995;48:390–401. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiowski W, Linder L, Stoschitzky K, Pfisterer M, Burckhardt D, Burkart F, Buhler Diminished vascular response to inhibition of endothelium-derived nitric oxide and enhanced vasoconstriction to exogenously administered endothelin-1 in clinically healthy smokers. Circulation. 1994;90:27–34. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cases E, Vila JM, Medina P, Aldasoro M, Segarra G, Lluch S. Increased responsiveness of human pulmonary arteries in patients with positive bronchodilator responses. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1337–1340. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helset E, Lindal S, Olsen R, Myklebust R, Jorgensen L. Endothelin-1 causes sequential trapping of platelets and neutrophils in pulmonary microcirculation in rats. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:L538–L546. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.271.4.L538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halim A, Kanayama N, El Maradny E, Maehara K, Mashiko H, Terao T. Activated neutrophils by endothelin-1 caused tissue damage in human umbilical cord. Thromb Res. 1995;77:321–327. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(95)93835-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida K, Takeshige K, Minakami S. Endothelin-1 enhances superoxide generation of human neutrophils stimulated by the chemotactic peptide N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenalanine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:496–500. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Garre D, Guerra M, Gonzalez E, Lopez-Farre A, Riesco A, Caramelo C, Escanero F, Egido J. Aggregation of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes by endothelium: role of platelet activating factor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;224:167–172. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90801-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helset E, Ytrehus K, Tveita T, Kjaeve J, Jorgensen L. Endothelin-1 causes accumulation of leukocytes in the pulmonary circulation. Circ Shock. 1994;44:201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Tipoe G, Lam W-K, Ho JCM, Shum I, Ooi GC, Leung R, Tsang KWT. Endothelin-1 in stable bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:146–149. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a26.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis I, Yousem S, Griffith B. Airway obstruction and bronchiolitis obliterans after lung transplantation. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14:751–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schersten H, Hedner T, McGregor CGA, Miller VM, Martensson G, Riise GC, FN Nilsson. Increased levels of endothelin-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in patients with lung allografts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:253–258. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarnio P, Tukiainen P, Taskinen E, Harjula A, Fyhrquist F. Endothelin in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid is increased in lung transplant patients. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;30:113–116. doi: 10.3109/14017439609107255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Sawa Y, Minami M, Kaneda Y, Fujii Y, Shirakura R, M Yanagisawa, Matsuda H. Experimental bronchiolitis obliterans induced by HVJ-liposome mediated endothelin-1 gene transfer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63:1562–1567. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizumi M, Kurihara H, Sugiyama T, Takaku F, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Yazaki Y. Hemodynamic shear stress stimulates endothelin production by cultured endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;161:859–864. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92679-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins BA, Hu R-M, Nazario B, Pedran A, Frank HJL, Weber MA, Levin ER. Prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin inhibit the production and secretion of endothelin from cultured endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11938–11944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markewitz BA, Kohan DE, Michael DR. Hypoxia decreased endothelin-1 synthesis by rat lung endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:L215–L220. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.2.L215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael JR, Markewitz BA, Kohan DE. Oxidant stress regulates basal endothelin production by cultured rat pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L768–L744. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CL, Kohler JD, Nick HS, Visner GA. Effects of vasoactive and inflammatory mediators on endothelin-1 expression in pulmonary endothelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1995;12:503–512. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.12.5.7742014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Chen SJ, Cheng Q, Durand J, Oparil S, Elton TS. Enhanced endothelin-1 and endothelin receptor gene expression in chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:1452–1459. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.3.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassoun PM, Thappa V, Landman MJ, Fanburg BL. Endothelin 1: mitogenic activity on pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and release from hypoxic endothelial cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1992;166:165–170. doi: 10.3181/00379727-199-43342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aversa CR, Oparil S, Caro J, Li H, Sun S-D, Chen Y-F, Swerdel MR, Monticello TM, Durhan SK, Minchenko A, Lira SA, Webb ML. Hypoxia stimulates human prepro endothelin-1 promoter activity in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L848–L855. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibke JL, Montrose-Rafizadeh C, Zeitlein PL, Guggino WB. Effect of hypoxia on endothelin-1 production by vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1992;1134:105–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(92)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuroda T, Kobayashi M, Ozaki S, Yano M, Miyauchi T, Onizuka M, Sugishita Y, Goto K, Nishikibe M. Endothelin receptor subtypes in human vs rabbit pulmonary arteries. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:1976–1982. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.5.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soma S, Takahashi H, Muramatsu M, Oka M, Fukudu Y. Localization and distribution of endothelin receptor subtypes in pulmonary vasculature of normal and hypoxia exposed rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:620–630. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyana H, Miyamori I, Yamagishi S, Takeda Y, Takeda H, Yamamoto H. Angiotensin II up-regulates the expression of type A endothelin receptors in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;34:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Elton TS, Chen Y-F, Oparil S. Increased endothelin receptor gene expression in hypoxic rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L553–L560. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.5.L553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNucci G, Thomas R, D'Orleans-Juste , Antunes E, Walder C, Warner TD, Vane JR. Pressor effects of circulating endothelin are limited by its removal in the pulmonary circulation and by the release of prostacyclin and endothelium derived relaxing factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9797–9800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasunuma K, Rodman DM, O'Brien RF, McMurtry IF. Endothelin-1 causes pulmonary vasodilation in rats. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:H48–H54. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.1.H48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu M, Oka M, Morio Y, Soma S, Takahashi H, Fukuchi Y. Chronic hypoxia augments endothelin-B receptor mediated vasodilation in isolated perfused rat lung. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L358–L364. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.2.L358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Rodman DM, McMurtry IF. Hypoxia inhibits ETB receptor mediated NO synthesis in hypoxic rat lungs. Am J Physiol. 1999;270:L511–L518. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.4.L571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu M, Rodman DM, Oka M, MucMurtry IF. Endothelin-1 mediated nitro-L-arginine vasoconstriction of hypertensive rat lungs. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L807–L812. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean MR, McCulloch KM, Baird M. Endothelin ETA- and ETB-receptor mediated vasoconstriction in rat pulmonary arteries and arterioles. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1994;23:838–845. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199405000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeck J, Gluth H, Mihaljevic N, Born M, Wendel-Wellner M, Krafft P. ET-1 induced vasoconstriction shifts from ETA- to ETB-receptor mediated reaction after preconstriction. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:2284–2289. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oparil S, Chen SJ, Meng Q-C, Elton TS, Yano M, Chen Y-F. Endothelin-A receptor antagonist prevents acute hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:L95–L100. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.268.1.L95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Morio Y, Morris KG, Rodman DM, McMurtry IF. Mechanism of hypoxic vasoconstriction involves ETa receptor-mediated inhibition of K-ATP channels. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:L434–L442. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.3.L434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K, Tajima F, Nakata Y, Osada H, Tachibana S, Kawai T, Torihata L, Suga T, Takishina K, Aurues T, Ikeda T. Expression of endothelin-1 in rats developing hypobaric-hypoxia induced pulmonary hypertension. Lab Invest. 1999;79:1347–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCarlo VS, Chen SJ, Meng QC, Durand J, Yano M, Chen Y-F, Oparil S. ETA-receptor antagonist prevents and reverses chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in rat. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:L690–L697. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1995.269.5.L690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvallet ST, Zamora MR, Hasunuma K, Sato K, Hanasato N, Anderson D, Sato K, Stelzner TJ. BQ-123, and ETa-receptor antagonist, attenuates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1327–H1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre JT, Morrell NW, Long L, Clift P, Upton PD, Polak JM, Wilkins MR. Vascular remodeling and ET-1 expression in rat strains with different responses to chronic hypoxia. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:L981–L987. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.5.L981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelzner TJ, O'Brien RF, Yanigisawa M, Sakurai T, Sato K, Webb S, Zamora MR, Fisher JH. Increased lung endothelin-1 production in rats with idiopathic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:L614–L620. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1992.262.5.L614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasch HF, Marshall C, Marshall BE. Endothelin-1 is elevated in monocrotaline pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L304–L310. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.2.L304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NS, Warburton RR, Pietras L, Klinger JR. Nonspecific endothelin-receptor antagonist blunts monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1209–1215. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.4.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor AM, Honda M, Saida K, Ishinaga Y, Kuramochi T, Maeda A, Takabatahe T, Mitsui Y. Endothelin induced collagen remodeling in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;210:981–986. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi T, Yorikani R, Sakai T, Sakurai T, Okada M, Nishikibe M, Yano M, Yamaguchi I, Sugishita Y, Goto K. Contribution of endogenous endothelin-1 to the progression of cardiopulmonary alterations in rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 1993;73:887–897. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora MR, Stelzner TJ, Webb S, Panos RJ, Ruff LJ, Dempsey EC. Overexpression of endothelin-1 and enhanced growth of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from fawn hooded rat. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L101–L109. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.1.L101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocher B, Schwarz A, Fagan KA, Thone-Reineke C, El-Hag K, Kusserow H, Elitok S, Bauer C, Neumayer H-H, Rodman DM, Theuring F. Pulmonary fibrosis and chronic lung inflammation in ET-1 transgenic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:19–26. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.1.4030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SD, Shroyer KR, Markham NE, Cool CD, Voelkel NF, Tuder RM. Monoclonal endothelial cell proliferation is present in primary but not secondary pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:927–934. doi: 10.1172/JCI1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DJ, Levy RD, Chernacek P, Langleben D. Increased plasma endothelin-1 in pulmonary hypertension: marker or mediator of disease. Ann Int Med. 1991;114:464–469. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-6-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaid A, Yanagisawa M, Langleben D, Michel RP, Levy R, Shennib H, Kimura S, Masaki T, Duguid WP, Path FRC, Stewart DJ. Expression of endothelin-1 in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. New Engl J Med. 1993;328:1732–1739. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199306173282402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacoub P, Dorent R, Nataf P, Carayon A, Riquet M, Noe E, Piette JC, Godeau P, Gandjbakhch I. Endothelin-1 in the lungs of patients with pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:196–200. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langleben D, Barst RJ, Badesch D, Groves BM, Tapson VF, Nurali S, Bourge RC, Ettinger N, Shalit E, Clayton LM, Jobsis MM, Blackburn SD, Crow JW, Stewart DJ, Long W. Continuous infusion of epoprostenol improves the net balance between pulmonary endothelin-1 clearance and release in primary pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 1999;99:3266–3271. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.25.3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shennib H, Serrick C, Saleh D, Reis A, Stewart DJ, Giaid A. Plasma endothelin-1 levels in human lung transplant recipients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26 (suppl 3):S516–S518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeppsson A, Tazelaar HD, Miller VM, McGregor CGA. Distribution of endothelin-1 in transplanted human lungs. Transplantation. 1998;66:806–809. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199809270-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaid A, Polak JM, Gaitonde V, Hamid QA, Moscoso G, Legon S, Uwanogho D, Roncalli M, Shinmi O, Sawamira T, Kimura S, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Springall DR. Distribution of endothelin-like immunoreactivity and mRNA in the developing and adult human lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1991;4:50–58. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/4.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cale ARJ, Ricagna F, Wiklund L, McGregor CGA, Miller VM. Mononuclear cells from dogs with acute lung allograft rejection cause contraction of pulmonary arteries. Circulation. 1994;90:952–958. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YD, Springall DR, Hamid Q, Yacoub MH, Levene M, Polak JM. Localization and characterization of endothelin-1 binding sites in the transplanted human lung. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;26 (suppl 3):S336–S340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison RC, Kyle J, Adkins WK, Prasad VR, McCord JM, Taylor AE. Effect of ischemia reperfusion or hypoxia reoxygenation on lung vascular permeability and resistance. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:597–603. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shennib H, Serrick C, Saleh D, Adoumie R, Stewart J, Giaid A. Alterations in bronchoalveolar lavage and plasma endothelin-1 levels early after lung transplantation. Transplantation. 59:994–998. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199504150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi S, Smedira N, Murray PA. Pulmonary vasoregulation by endothelium in conscious dogs after left lung transplantation. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:210–218. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shennib H, Lee AGL, Kuang JQ, Yanagisawa M, Ohlstein EH, Giaid A. Efficacy of administering an endothelin-receptor antagonist (B209670) in ameliorating ischemia-reperfusion injury in lung allografts. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998:1975–1981. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9709131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemulapalli S, Rivelli M, Chin PJS, delPrado M, Hey JA. Phosphoramidon abolishes the increased in endothelin-1 release induced by ischemia-hypoxia in isolated perfused guinea pig lungs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:1062–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunose Y, Takeyoshi I, Ohwada S, Iwazaki S, Aiba M, Tomizawa N, Tsutsumi H, Oriuchi N, Matsumoto K, Morishita Y. The effect of FK409 - a nitric oxide donor - on canine lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transpl. 2000;19:298–309. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(99)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schersten H, Aarino P, Burnett JC, McGregor CGA, Miller VM. Endothelin-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage during rejection of allotransplanted lungs. Transplantation. 1994;57:159–161. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199401000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JP, Higenbottam TW, Sharples L, Clelland CA, Smyth RL, Stewart S, Wallwork J. Risk factors for obliterative bronchiolitis in heart-lung transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1991;51:813–817. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199104000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin D, Pratt RE, Cooke JP, Dzau VJ. Endothelin, a potent vasoconstrictor is a vascular smooth muscle mitogen. J Vasc Med Biol. 1989;1:150. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JB, Chan-Tack K, Hedican SP, Magnuson SR, Opgenorth , Bova GS, Simons JW. Endothelin-1 and decreased endothelin B receptor expression in advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:663–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali H, Loizidou M, Dashwood M, Savage F, Sheard C, Taylor I. Stimulation of colorectal cancer cell line growth by ET-1 and its inhibition by ET(A) antagonists. Gut. 2000;47:685–688. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drimal J, Drimal J, Drimal D. Enhanced endothelin ETB receptor down-regulation in human tumor cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;396:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanen K, Deng DX, Chakrabarti S. Augmented expression of endothelin-1, endothelin-3, and the endothelin-B receptor in breast carcinoma. Histopathology. 2000;36:161–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahav R, Heffner G, Patterson PH. An endothelin receptor b antagonist inhibits growth and induces cell death in human melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11496–11500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl LP, Valdenaire O, Saintgiorgio V, Jeannin JF, Juillerat-Jenneret L. Endothelin receptor blockade potentiates FasL-induced apoptosis in rat colon carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2000;86:182–187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000415)86:2<182::AID-IJC6>3.3.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaid A, Hamid QA, Springall DR, Yanagisawa M, Shinmi O, Sawamura T, Masaki T, Kimura S, Corrin B, Polak JM. Detection of endothelin immunoreactivity and mRNA in pulmonary tumors. J Pathol. 1990;162:15–22. doi: 10.1002/path.1711620105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AJ, Gilman LB, Miller YE. Endothelin receptor expression in lung cancer cell lines and bronchial epithelial cell lines [abstract]. FASEB J. 1997;11:A3221. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AJ, Yanagisawa M, Zamora M, Gilman L, Bunn P, Franklin W, Miller Y. Evidence for an endothelin-1 autocrine loop in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 1997;18 (suppl):574. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SI, Thompson J, Coulson JM, Woll PJ. Studies on the expression of endothelin, its receptor subtypes and converting enzymes in lung cancer and human bronchial epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;22:422–431. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.4.3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Hu R-M, Levin E. Vasoactive peptides modulate vascular endothelin cell growth factor production and endothelial cell proliferation and invasion. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17097–17103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawas K, Loizidou M, Shankar A, Ali H, Taylor I. Angiogenesis in cancer: the role of endothelin-1. Ann R Coll Surg Eng. 1999;81:306–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YD, Springall DR, Hamid Q, Levene M, Polak JM. Localization and characterization of endothelin-1 receptor binding in the blood vessels of human pulmonary tumors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;261 (suppl 3):S341–S345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Chaplin DM. The effect of oxygen and carbon dioxide on tumor endothelin-1 production. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;33 (suppl 3):S537–S540. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199800001-00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmet T, Pritze S, Thelen KI, Peskar BA. Released endothelin in oleic acid-induced respiratory distress syndrome. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;211:319–322. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90387-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druml W, Steltzer H, Waldhausl W, Lenz K, Hammerle A, Vierhapper H, Gasic S, Wagner OF. Endothelin-1 in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1169–1173. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.5.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai L, Haynes WG, Mackenzie A, Grant IS, Webb DJ. Endothelin production in sepsis and the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:52–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01728331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langleben D, DeMarchie M, Laporta D, Spanier AH, Schlesinger RD, Stewart DJ. Endothelin-1 in acute lung injury and the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:1646–1650. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.6_Pt_1.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakura H, Jokaji H, Saito M, Uotani C, Kumabashiri I, Morishita E, Yamazaki M, Matsuda T. Role of endothelin in disseminated intravascular coagulation. Am J Hematol. 1992;41:71–75. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830410202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huribal M, Cunningham ME, D'Aiuto ML, Pleban WE, McMillen MA. Endothelin-1 and prostaglandin E2 levels increase in patients with lung injury. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitaka C, Hirata Y, Nagura T, Tsunoda Y, Amaha K. Circulating endothelin-1 concentrations in acute respiratory failure. Chest. 1993;104:476–480. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.2.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertine KH, Wana ZM, Michael JR. Expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, inducible nitric oxide synthase and endothelin-1 in lungs of subjects who died with ARDS. Chest. 1999;116:1015–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen MA, Sumpio BE. Endothelins: polyfunctional peptides. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:621–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehoux S, Plante GE, Sirois MG, Sirosis P, D'Orleans-Juste P. Phosphoramidon blocks big-endothelin-1 but not endothelin-1 enhancement of vascular permeability in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;107:996–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb13397.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helset E, Kjaeve J, Hauge A. Endothelin-1-induced increase in microvascular permeability in isolated perfused rat lungs requires leukocytes and plasma. Circ Shock. 1993;39:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodman DM, Stelzner TJ, Zamora MR, Bonvalet ST, Oka M, Sato K, O'Brien RF, McMurtry IF. Endothelin-1 increases the pulmonary microvascular pressure and causes pulmonary edema in salt-solution but not blood perfused rat lungs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20:658–663. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199210000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filep JG, Foldes-Filep E, Rousseau A, Sirois P, Fournier A. Vascular responses to endothelin-1 following inhibition of nitric oxide synthase in the conscious rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:1213–1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeck J, Heller A, Groschler A, Recker A, Neuhof H, Urbascheck R, Koch T. Impact of endothelin-1 in endotoxin-induced pulmonary vascular reactions. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2851–2857. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida Y, Ninomiya N, Sakamoto T, Lee JY, Endo T, Nomura A, Hasegawa S, Hirata F. ET-1 released histamine from guinea pig pulmonary but not peritoneal mast cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)92331-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil N, Bereznay O, Sporn M, Greenberg AH. Macrophage production of transforming growth factor beta and fibroblast collagen synthesis in chronic pulmonary inflammation. J Exp Med. 1989;170:727–737. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet PF, Collart MA, Grau GE, Kapanci Y, Vassalli P. Tumor necrosis factor/cachectin plays a key role in bleomycin-induced pneumopathy and fibrosis. J Exp Med. 1989;170:655–663. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock AJ, Dawes KE, Shock A, Gray AJ, Reeves JT, Lauert GL. Endothelin 1 and endothelin 3 induced chemotaxis and replication of pulmonary fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:492–499. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/7.5.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar I, Fireman E, Topilsky M, Grief J, Schwarz Y, Kivity S, Ben-Efrain S, Spirer Z. Effect of endothelin-1 on alpha smooth muscle actin expression and on alveolar fibroblast proliferation in interstitial lung diseases. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1999;21:759–775. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(99)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambrey AD, Harrison NK, Dawes KE, Southcott AM, Black CM, DuBois DM, Laurent GL, McAnulty RJ. Increased levels of endothelin-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with systemic sclerosis contribute to fibroblast migration and activity in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1994;11:439–445. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.11.4.7917311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry C, Hook M. Endothelin produced by endothelial cells promotes collagen gel contraction by fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:873–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarda E, Katwa LC, Myers PR, Tyagi SC, Weber KT. Effects of endothelins on collagen turnover in cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovsac Res. 1993;27:2130–2134. doi: 10.1093/cvr/27.12.2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaschi S, Nicosia RF. Paracrine interaction between fibroblast and endothelial cells in a serum-free coculture model: modulation of angiogenesis and collagen gel contraction. Lab Invest. 1994;71:291–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]