Abstract

Sexual assault is a troubling epidemic that plagues college campuses across the United States, and is often proceeded by drinking by the perpetrator and/or victim. The goal of this study was to examine the effect of level of intoxication, history of alcohol-related blackouts, and childhood sexual abuse (CSA) on the likelihood of being a victim or perpetrator of coercive sexual activities. Participants (N=2,244) were part of a six-year longitudinal study which explored alcohol use and associated behavioral risks during college. A subsample (N=1,423) completed 30 days of daily diary surveys across four years of college. Participants provided daily reports of their alcohol consumption, sexual coercion perpetration, and sexual coercion victimization. Using hierarchical linear models, results indicated that increases in daily estimated blood alcohol concentration (eBAC) were associated with a greater likelihood of being a victim and a perpetrator of sexual coercion. In addition, main effects of CSA and history of blackouts predicted a greater likelihood of being coerced into sexual activity, but blackouts were not associated with being a perpetrator. A significant interaction between blackouts and event-level eBAC indicated that individuals with a history of blackouts had a greater likelihood of sexual coercion victimization relative to those without prior blackouts. Finally, having a history of blackouts and CSA was predictive of a lower likelihood of being a perpetrator of sexual coercion at higher eBACs relative to those without a history of blackouts. Thus, prevention efforts should integrate the impact of blackouts and CSA on sexual coercion victimization and perpetration.

Keywords: Alcohol-Related Blackouts, Sexual Coercion, Childhood Sexual Abuse

Introduction

The epidemic of sexual assault on college campuses has become so troubling that it received national attention by then President of the United States, Barack Obama, who called for better transparency and prevention efforts to protect against perpetration of sexual assault. In accordance with the former President, it is unequivocally the time to act, as approximately 23% of female and 5% of male college students report sexual assault and sexual misconduct while in school (Association of American Universities, 2015). Further substantiating the need for action, recent research indicates that a striking 38% of rape victims experience their first rape during college (Breiding, 2014). Although great efforts have been taken to reduce sexual victimization on college campuses, we must take further steps to identify and understand specific risk factors if we hope to improve prevention and intervention methods.

In the present study, we employed a longitudinal event-level design across four years to investigate three factors that alone or in combination may increase the likelihood of sexual coercion victimization and perpetration on college campuses; specifically, level of intoxication, alcohol-related blackouts, and history of childhood sexual abuse (CSA). Importantly, for our analyses we examined sexual coercion victimization and perpetration as the outcome, which was defined broadly to include coercive behavior that led to some form of sexual activity. This outcome could encompass rape, defined as sexual penetration due to force, threat, or lack of consent (Abbey, 2002), but could also include coercive sexual behavior other than penetration. Thus, subsequent consideration of our findings should be interpreted according to this definition.

Alcohol Intoxication in Relation to Sexual Victimization and Perpetration

It is well established that alcohol is closely tied to sexual victimization, defined broadly to include sexual assault, coercive sexual behavior, and rape, with heavier use increasing the occurrence of sexual victimization. In particular, women with a history of rape consumed more alcohol than non-victims (Messman-Moore, Coates, Gaffey, & Johnson, 2008). Further, a 12 month longitudinal study of women found that drinking during an assessment month increased the likelihood of being a victim during the same period (Bryan et al., 2016). Additionally, heavy episodic drinking, or consuming four or more beverages for a woman, confers particularly large risk for sexual assault victimization (Howard, Griffin, & Boekeloo, 2008), which highlights that level of intoxication, not just alcohol use generally, may play an important role in risk for sexual victimization.

Some cross-sectional research shows that alcohol use can confer risk for sexual violence perpetration (Tharp et al., 2013), as alcohol use before the event by both the perpetrator and victim has been associated with more severe victimization (Ullman, Karabatsos, & Koss, 1999). Perpetrators have a tendency to hold stronger beliefs that alcohol increases their sex drive and they tend to consume alcohol prior to sexual acts more often than non-perpetrators (Abbey, McAuslan, Zawacki, Clinton, & Buck, 2001). Finally, those who perpetrated sexual violence while drinking tended to have higher levels of impulsivity, stronger beliefs that alcohol promotes sexual behavior, and to perceive women’s drinking as a sexual cue (Zawacki, Abbey, Buck, McAuslan, & Clinton-Sherrod, 2003) relative to those who perpetrated without alcohol. Further, a review of experimental and self-report surveys highlighted alcohol as a key risk factor for sexual aggression perpetration (Abbey, Wegner, Woerner, Pegram, & Pierce, 2014).

Contrary to key findings from cross sectional studies, one longitudinal examination showed that neither the between nor the within-person effect of heavy episodic drinking was associated with sexual assault perpetration across five semesters of college, when controlling for several individual difference factors (Testa & Cleveland, 2016). Further, in another longitudinal sample of male college students, changes in heavy drinking across time were not associated with increased perpetration of sexual aggression (Thompson, Swartout, & Koss, 2013). Additionally, alcohol use was only associated with sexual aggression, defined as sexual activity influenced by verbal persuasion, physical force, or encouragement to drink, for new sexual partners, but not previous partners, indicating a complex association between alcohol and sexual perpetration (Testa et al., 2015). These longitudinal studies challenge whether alcohol increases the risk of sexual perpetration.

Despite these complex findings, only two prior daily diary event-level studies have examined the within-person effect of level of intoxication on sexual coercion perpetration (Neal & Fromme, 2007; Testa et al., 2015). Using daily surveys assessed during the first year of college, one prior study found men who reported higher levels of intoxication were more likely to engage in sexual coercion perpetration (Neal & Fromme, 2007). Additionally, in a sample using daily measures there is support that within-person variation in level of intoxication relates to increased general aggression (Quinn, Stappenbeck, & Fromme, 2013), which may extend to sexual perpetration. Thus, this paper aims to provide further clarity about the proximal effect of level of intoxication as a risk factor for sexual coercion perpetration across the span of college.

Alcohol-related Blackouts in Relation to Sexual Victimization and Perpetration

One potential negative consequence of heavy drinking is alcohol-related blackouts, which are episodes of amnesia during a drinking event whereby memories are not formed. Blackouts are caused by an impairment in the ability to transfer information from short-term to long-term memory (White, 2003). This can lead to partial or complete loss of memory for events or activities while drinking. Blackouts are common after rapid consumption of alcohol, but are only experienced by roughly 50–60% of college drinkers (Wetherill & Fromme, 2009; Marino & Fromme, 2016). Further, while experiencing an alcohol-related blackout, individuals are able to engage in a multitude of behaviors including driving, having conversations, and getting into arguments (White, Jamieson-Drake, & Swartzwelder, 2002).

Unsurprising given the nature of forgetting episodes of time, alcohol-related blackouts are often experienced as upsetting (Buelow & Koeppel, 1995; White et al., 2004). They are associated with myriad negative outcomes including social and emotional consequences (Wilhite & Fromme, 2015), alcohol-related injuries (Mundt, Zakletskaia, Brown, & Fleming, 2012), suicidal ideation (Bae, Hong, Jang, Lee, & Park, 2015), and doing something that was later regretted (Hingson, Zha, Simons-Morton, & White, 2016). These results highlight that alcohol-related blackouts appear to confer additional risk for negative outcomes, independent of heavy drinking alone. It may be that individuals who are predisposed to alcohol-related blackouts engage in riskier, unplanned behavior while drinking, potentially a result of neural differences related to inhibitory processing (Wetherill, Castro, Squeglia, & Tapert, 2013). In particular, a quarter of men and women reported engaging in sexual behavior while in a blackout, highlighting the frequency with which sexual behavior occurs during a blackout (White et al., 2002). Thus, we believe that in addition to higher levels of intoxication, being at risk for alcohol-related blackouts may contribute to even greater risk for victimization and perpetration of sexual coercion relative to those without a history of blackouts, perhaps because of neurological (e.g., inhibitory) differences.

Only two prior studies have examined the association between alcohol-related blackouts and sexual victimization. In a sample of college women, having a history of adolescent sexual victimization and experiencing a blackout during the past three months increased the likelihood of being revictimized at a 30 day follow up, although blackout drinking alone did not predict revictimization (Valenstein-Mah, Larimer, Zoellner, & Kaysen, 2015). Further, in a sample of college students with a history of blackouts, 4% of men and 6% of women reported unwanted intercourse while in a blackout (White et al., 2002). Another study examined blackouts in relation to sexual risk taking and found that women who experienced blackouts were at much greater risk of sexual risk-taking behaviors, including unplanned sexual behavior, relative to those without a blackout history (Haas, Barthel, & Taylor, 2017). Moreover, being in a blackout may also increase the risk for sexual coercion perpetration, as inhibitory processing necessary to refrain from sexual perpetration is impaired for those with a history of blackouts relative to typical heavy drinkers without a history of blackouts (Wetherill et al., 2013). Thus, the current study examined whether having a history of alcohol-related blackouts is a risk factor for sexual coercion victimization or perpetration. Whereas there is evidence that alcohol use confers risk for both victimization and perpetration, other factors, such as CSA, may further contribute to a greater likelihood of sexual coercion victimization and perpetration.

History of CSA in Relation to Sexual Victimization and Perpetration

A history of CSA has been associated with increased likelihood of sexual victimization in adolescence and adulthood. For example, women with a history of CSA were twice as likely as women without such history to report rape during adulthood (Messman-Moore & Brown, 2004), while those with a history of CSA involving sexual intercourse were 11 times more likely to be raped in adulthood relative to those without an abuse history (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1997). This pattern of repeated victimization is important, as it confers greater risk for trauma-related symptoms in adulthood (Follette, Polusny, Bechtle, & Naugle, 1996). The reason for the connection between CSA and revictimization is complex, with some evidence that those with a history of CSA engage in riskier sexual behaviors (Senn, Carey, & Vanable, 2008) and higher rates of problematic drinking in adulthood (Messman-Moore et al., 2008), both factors that could increase the risk for revictimization in adulthood. This study extended prior work by using event-level data to test whether within-person level of intoxication may have a stronger effect on sexual coercion victimization for those with a history of CSA relative to those without a history of CSA.

There is conflicting evidence about the influence of CSA on perpetration of sexual victimization in adulthood. Some evidence suggests that CSA is more common among male sexual offenders than the general population (Romano & Luca, 1997), whereas other research shows no prospective link between CSA and violence towards women in adulthood (Loh & Gidycz, 2006). Yet, evidence shows that a history of CSA is associated with a greater likelihood of perpetrating physically forced sex and verbal sexual coercion for both men and women (Gámez-Guadix, Straus, & Hershberger, 2011). There is also evidence that CSA is directly and indirectly associated with sexual assault perpetration (Casey et al., 2017). Potential explanations for this phenomenon include the idea that men with CSA histories have a desire to establish masculinity, an identification with aggressors, an urge to regain control, have been socialized towards aggression (Abbey, Zawacki, Buck, Clinton, & McAuslan, 2004), or endorse higher rates of hostile masculinity (Casey et al., 2017). Importantly, research on CSA and perpetration often use different definitions of CSA. The current study defined CSA as sexual abuse before the age of 18 perpetrated by an adult at least five years older. Overall, our current study adds to the existing literature by examining whether a history of CSA predisposed individuals towards sexual coercion perpetration at increasing levels of intoxication.

The Present Study

We employed a longitudinal event-level approach to investigate the effects of alcohol consumption, blackouts, and CSA on the likelihood of sexual coercion victimization and perpetration during college. Participants were asked if they were coerced or coerced someone else into some form of sexual activity. We did not specify whether “coercion” involved verbal or physical means, nor did we specify the type of “sexual activity.” As a follow up to previous daily monitoring analyses (Neal & Fromme, 2007), we first predicted that higher estimated blood alcohol concentration (eBAC) would be associated with a greater likelihood of sexual coercion victimization. Second, we were also interested in the effect of between-person variables on sexual coercion victimization. Specifically, we predicted that there would be a main effect of both alcohol-related blackouts and CSA on sexual coercion victimization assessed during a series of daily monitoring surveys during college. Third, based on prior findings that have found blackouts and CSA to be risk factors for hazardous drinking and risky sexual behavior, we predicted that between-person history of blackouts and CSA will interact with within-person eBAC, conferring even greater risk of victimization as levels of intoxication rise. Fourth, we predicted that eBAC, history of blackouts, and history of CSA will be independently associated with a greater likelihood of sexual coercion perpetration. Fifth, we predicted that histories of blackout and CSA will each independently interact with eBAC, further predisposing individuals with those histories to sexual coercion perpetration. Finally, given evidence that each of these variables has been related to increased risk for sexual coercion victimization and perpetration, we predicted that the combination of higher eBAC, a history of blackouts, and a history of CSA would be associated with greater likelihood of sexual coercion victimization and perpetration relative to no history of these between-person variables. These three-way interactions were novel and were primarily exploratory. We also included self-reported biological sex as an exploratory covariate of interest in all statistical models, but we posed no formal hypotheses regarding sex differences in our outcome variables (i.e., sexual coercion victimization and perpetration).

Method

Participant Characteristics

The present sample (N=1,423) was drawn from a larger cohort that participated in a longitudinal investigation of alcohol use and other behavioral risks among college students. This subsample consisted of participants that provided valid responses to the history of alcohol-related blackout and CSA questions, as well as sufficient numbers of daily responses to pass the quality control thresholds described below. At the first wave of data collection, the average age of participants was 18.40 years (SD=0.35). The final sample was 65% female and 54% of participants identified as White, 20% as Asian, 14% as Hispanic or Latino, 4% as African American, and 8% as multi-ethnic or other ethnicities. Recruitment procedures for the larger study have been described in previously published articles (Fromme, Corbin, & Kruse, 2008) (Corbin, Iwamoto, & Fromme, 2011; Ashenhurst, Harden, Corbin, & Fromme, 2015). All procedures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Longitudinal Design and Measures

In August of 2004, the incoming class of first-year college students at a large public university in the southwest United States was invited to participate in a longitudinal study if they met the criteria of (a) being a first-time student and (b) were between 17 and 19 years of age (N = 6,390; 94% of the incoming class). Of these students, approximately 75.6% (N = 4,832) expressed interest in participating in the study by completing a contact information form and met the final criterion of being unmarried. A subset of these students was successfully recruited and randomized to the semi-annual assessment condition (N = 3,046), where 2,244 (73.7%) students provided informed consent and completed the first online survey (Wave 1). Participants were paid $25 for completion of the Wave 1 survey.

For the purposes of the present study, demographics (age, sex, and ethnicity) were reported at Wave 1. History of CSA was collected by asking “Before the age of 18, how many times did you experience unwanted sexual contact by adult more than 5 years older than you?” and was assessed in Waves 8–10 of data collection. History of blackout was determined by asking “While you were drinking or because of your drinking: During the last 3 months, how many times have you suddenly found yourself in a place that you could not remember getting to?” (White & Labouvie, 1989) and it was assessed in every wave of data collection. Only responses from Waves 1, 3, 5, and 7 were analyzed, as those waves preceded participants’ annual daily monitoring periods. Both history of CSA and history of blackout were dichotomized. That is, if the respective items were endorsed at all, they were recoded as ‘1’ in order to indicate a positive history. Measures of eBAC and sexual coercion victimization and perpetration were assessed in the daily monitoring questionnaires.

Event-Level Design and Measures

At the onset of the study, a random selection of 200 participants was invited to participate in the daily monitoring portion of the study to ensure sufficient monitoring in the first weeks of the study. Subsequently, 40–43 participants were invited to complete daily monitoring surveys in each week throughout the calendar year. Participants were asked to log onto a secure website (hosted by Datstat) where they could complete their online daily monitoring surveys during the same 30-day period each year to control for the influence of time-dependent environmental factors (e.g., final examination schedule). Participants were asked to complete the daily surveys each morning about the previous night’s behaviors but were allowed to access the surveys for up to seven days to reduce missing data. For more information on this sample please see Neal & Fromme, 2007. Here, a sample of 1,463 participants provided enough data in the longitudinal Waves to be considered for the present analyses. An additional 40 participants were removed following the quality control procedures detailed below, which resulted in a final sample size of 1,423 participants with 123,530 observations (M ≈ 87 observations per individual, SD ≈ 27, range = 14 – 119).

During their daily monitoring, participants answered questions about the previous day via an online survey (maintained by DatStat, Seattle, WA). Participants were compensated $1 per day of monitoring, and received a $5 bonus for completing all 30 days within a given year of data collection. Additional information on daily monitoring recruitment and procedures can be found in previously published articles (Neal & Fromme, 2007; Quinn & Fromme, 2011, 2012).

For the purposes of the present study, each day participants answered questions about the previous day for time-varying demographics (e.g., weight), and for their alcohol consumption (“How many drinks did you consume yesterday?” and “Of the times that you drank this day, how long was your heaviest drinking episode?”), sexual coercion victimization (“Were [you] coerced into some form of sexual activity?”), and sexual coercion perpetration (“[Did you] coerce another person into some form of sexual activity?”). If participants endorsed sexual coercion victimization or perpetration on any given day, they were asked to specify whether the event occurred while sober or during a drinking episode. Following quality control procedures (see below), we identified 771 instances of victimization, 513 of which occurred while sober (0.42% of all sober observations) and 258 of which occurred during a drinking episode (1.51% of all alcohol-related observations). With regard to perpetration, 275 of 375 instances occurred while sober (0.22% of all sober observations) and 100 of 375 instances occurred during a drinking episode (0.58% of all alcohol-related observations).

Event-level estimates of blood alcohol content (eBAC) were calculated using self-reported data on sex, weight, quantity of drinks consumed, and duration of drinking episode (Matthews & Miller, 1979). Several studies have previously demonstrated the validity of eBAC as an objective measure of alcohol intoxication (Hustad & Carey, 2005). Moreover, researchers have recommended the use of eBAC when breath alcohol concentrations are not available (Leeman et al., 2010). In the present study, eBAC estimates were multiplied by 100, which means that the odds ratios for these variables reflect the increase in odds of the outcome associated with a .01 increase in eBAC. Year-specific averages of eBAC and total averages of eBAC were also calculated to assess within-person variation across college years and between-person effects of alcohol consumption, respectively.

Several steps were taken to maximize the reliability and validity of the daily monitoring data. First, to reduce bias due to over-exclusion or inclusion of noncompliant participants, participants who did not provide at least 14 days of monitoring data were excluded from analysis (N = 40). Second, 168 event-level eBAC values (0.98% of 17,100 estimates greater than zero) that exceeded 0.40 g/dl were winsorized (Hellerstein, 2008), as these were considered to be potentially erroneous estimates of BAC. That is, 168 values deemed to be outliers were changed to 0.40 g/dl, a value reflecting the reasonable maximum of the distribution. These measures are consistent with previous studies using this sample (e.g., Neal & Fromme, 2007; Quinn & Fromme, 2011, 2012), and ensured that the final sample (N = 1,423 participants, N = 123,530 observations) events was of high quality.

Analytic Approach

We used three-level hierarchical linear models (HLMs) with robust standard errors (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to examine the effects of alcohol intoxication, alcohol-related blackouts (0=no history, 1=positive history), and history of CSA (0=no history, 1=positive history) on dichotomous outcomes (i.e., sexual coercion victimization and perpetration). Victimization and perpetration were analyzed in separate models. In both models, events were nested within years and years were nested within participants. Moreover, these models included random intercepts and random slopes. That is, the intercept and slopes of each model were permitted to vary among participants. Self-reported gender (0=female, 1=male) was included as a covariate of interest in all statistical analyses. The final model is described below.

- LEVEL 1 MODEL

- LEVEL 2 MODEL

- LEVEL 3 MODEL

We analyzed sexual coercion victimization and perpetration outcomes with a logit model to estimate a log odds value for each participant that was subsequently converted to a probability. In the Level 1 (event level) equation, we modeled the likelihood of reporting sexual coercion victimization or perpetration as a function of a person-specific intercept (π0) and a slope describing change in the likelihood of sexual coercion victimization or perpetration as a function of event-level eBAC (π1). Event-level eBAC was entered into the model as group-centered (i.e., centered on the individual’s mean eBAC). Overall, the Level 1 equation tested whether the extent of alcohol intoxication (eBAC) predicted whether a person was more likely to be a victim or perpetrator on a given occasion, relative to other occasions.

In the Level 2 (year level) equation, we modeled variables as functions of the Level 1 variables described above. Specifically, the year-specific intercept for sexual coercion victimization/perpetration (π0) represented the yearly average likelihood of sexual victimization/perpetration (β00), the effect of a history of alcohol-related blackouts (β01), and yearly average eBAC (β02). The within-person eBAC slopes (π1) were modeled as a function of the average association of event-level eBAC and sexual outcomes across all individuals (β10), as well as the effect of a history of alcohol-related blackouts (β11) on this association (i.e., the cross-level interaction). Between-person residuals (r0 and r1) were included to allow for person-to-person heterogeneity in the magnitude of the within-person effects. Overall, the Level 2 model tested whether a history of alcohol-related blackouts and year-specific patterns of alcohol consumption predicted whether people were more likely to be sexual coercion victims or perpetrators on any given occasion, relative to occasions in other years.

Lastly, the Level 3 (person level) equation modeled variables as functions of the Level 2 variables, which are modeled as functions of the Level 1 variables. Here, the person-specific intercept for sexual coercion victimization/perpetration (β00) was modeled as the person-average likelihood of sexual coercion victimization/perpetration (γ000) across all reported events, the main effect of gender (γ001), the main effect of CSA history (γ002), and the main effect of person-average eBAC (γ003). The within-person association between blackout history and the likelihood of victimization/perpetration (β01) was modeled as a function of the average association of history of blackout and sexual outcomes across all individuals (γ010), as well as the interactions effects of gender (γ011) and CSA (γ012). The within-person slopes of sexual coercion victimization/perpetration on the main effect of event-level eBAC (β10), yearly average eBAC (β02) and the cross-level interactions of blackout history × event-level eBAC (β11) were modeled in the same fashion. Again, between-person residuals (u0, u1, u2, u3, u4, and u5) were included to model heterogeneity in the magnitude of the within-person effects. Overall, the Level 3 model tested whether the stable trait risk factors of gender, history of CSA, and average intoxication predicted whether people were more likely to experience sexual coercion victimization/perpetration on any given day.

Results

Over the course of the study, participants reported 771 instances of victimization and 375 instances of perpetration. Of the 1,423 individuals who participated in the present study, 292 (70% female; 21% of the total sample) reported at least one instance of sexual coercion victimization and 167 (63% female; 12% of the total sample) reported at least one instance of sexual coercion perpetration. Additional characteristics and demographics of the present sample are reported in Table 1. The results of our three-level HLMs are described in detail below.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and characteristics stratified by sex

| Male (n = 496) | Female (n = 927) | Total (N = 1,423) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 267 (53.83%) | 499 (53.83%) | 766 (53.83%) |

| Hx of CSA | 18 (3.63%) | 62 (6.69%) | 80 (5.62%) |

| Mean age at W1 (SD) | 18.44 (.37) | 18.38 (.34) | 18.40 (.35) |

| Hx of BO at W1* | 39 (7.86%) | 62 (6.69%) | 101 (7.13%) |

| Hx of BO at W3* | 66 (13.31%) | 124 (13.38%) | 190 (13.69%) |

| Hx of BO at W5* | 90 (18.14%) | 159 (17.25%) | 249 (18.40%) |

| Hx of BO at W7* | 107 (21.57%) | 205 (22.11%) | 312 (23.49%) |

Note: Hx of CSA = history childhood sexual abuse, Hx of BO = history of alcohol-related blackout, W1 = Wave 1 (Summer 2004), W3 = Wave 3 (Spring 2005), W5 = Wave 5 (Spring 2006), W7 = (Spring 2007). The effective sample size for descriptive statistics marked with an asterisk (*) varied slightly, as participants did not necessarily provide data every year.

Associations between Alcohol, Blackouts, CSA, and Victimization

Results for the victimization model are summarized in Table 2. Specifically, the results of our hierarchical linear model for victimization indicated main effects of male gender (B = −0.148, OR = 0.863, 95 CI = 0.805, 0.925) and history of blackout (B = −0.297, OR = 0.743, 95 CI = 0.636, 0.868) on the intercept of victimization, such that these factors were associated with a lower overall likelihood of sexual coercion victimization. We also observed a main effect of history of CSA (B = 0.016, OR = 1.016, 95 CI = 1.006, 1.027) on the intercept, which indicated that a positive history of CSA was significantly associated with an overall greater risk of victimization. Furthermore, our results suggested that the likelihood of sexual coercion victimization increased as a function of event-level eBAC (B = 0.044, OR = 1.045, 95 CI = 1.042, 1.048), and similar effects were observed for year-specific average eBAC (B = 0.015, OR = 1.016, 95 CI = 1.008, 1.023) and total average eBAC (B = 0.058, OR = 1.060, 95 CI = 1.053, 1.066).

Table 2.

Hierarchical linear models predicting the likelihood of sexual coercion outcomes

| MODEL FOR VICTIM | MODEL FOR PERPETRATOR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Coefficient | OR | 95% CI | Coefficient | OR | 95% CI |

| Event-level effects | ||||||

| eBACevent | 0.044*** | 1.045 | (1.042,1.048) | 0.034*** | 1.035 | (1.032,1.038) |

| eBACevent × Gender | 0.005 | 1.005 | (0.998,1.012) | 0.018*** | 1.018 | (1.011,1.024) |

| eBACevent × Hx CSA | 0.012 | 1.012 | (0.999,1.025) | 0.004 | 1.004 | (0.993,1.016) |

| eBACevent × Hx BO | 0.016** | 1.016 | (1.006,1.027) | −0.002 | 0.998 | (0.987,1.008) |

| eBACevent × Hx BO × Gender | −0.032*** | 0.969 | (0.954,0.983) | −0.002 | 0.998 | (0.982,1.015) |

| eBACevent × Hx BO × Hx CSA | 0.044* | 1.045 | (1.003,1.088) | −0.037*** | 0.964 | (0.953,0.975) |

| Year-level effects | ||||||

| Hx BO | −0.297*** | 0.743 | (0.636,0.868) | −0.147 | 0.864 | (0.753,0.991) |

| Hx BO × Gender | 0.011 | 1.011 | (0.789,1.297) | −0.578*** | 0.561 | (0.453,0.694) |

| Hx BO × Hx CSA | 0.185 | 1.203 | (0.839,1.724) | 1.167*** | 3.213 | (2.577,4.006) |

| eBACyear | 0.015*** | 1.016 | (1.008,1.023) | 0.009*** | 1.009 | (1.004,1.013) |

| eBACyear × Gender | 0.005 | 1.005 | (0.992,1.019) | −0.005 | 0.995 | (0.986,1.005) |

| eBACyear × Hx CSA | 0.006 | 1.012 | (0.987,1.025) | 0.010 | 1.010 | (0.999,1.021) |

| Trait-level effects | ||||||

| eBACaverage | 0.058*** | 1.060 | (1.053,1.066) | 0.018*** | 1.018 | (1.014,1.023) |

| Gender | −0.148*** | 0.863 | (0.805,0.925) | 0.045* | 1.046 | (1.000,1.094) |

| Hx CSA | 0.436*** | 1.547 | (1.371,1.746) | 0.133*** | 1.142 | (1.053,1.239) |

Note: Hx of CSA = history childhood sexual abuse, Hx of BO = history of alcohol-related blackout, eBAC = estimated blood alcohol concentration. OR = Odds ratio. CI = Confidence interval.

p-values significant at α = .001.

p-values significant at α = .01.

p-values significant at α = .01.

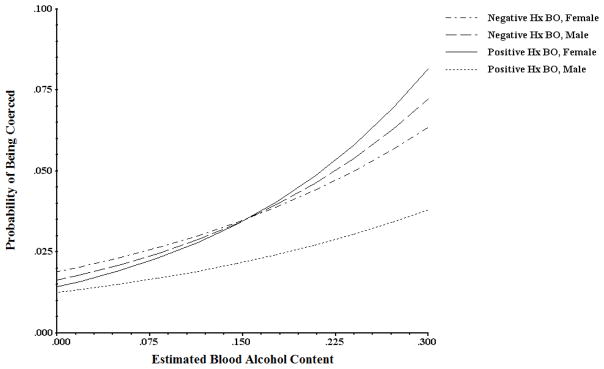

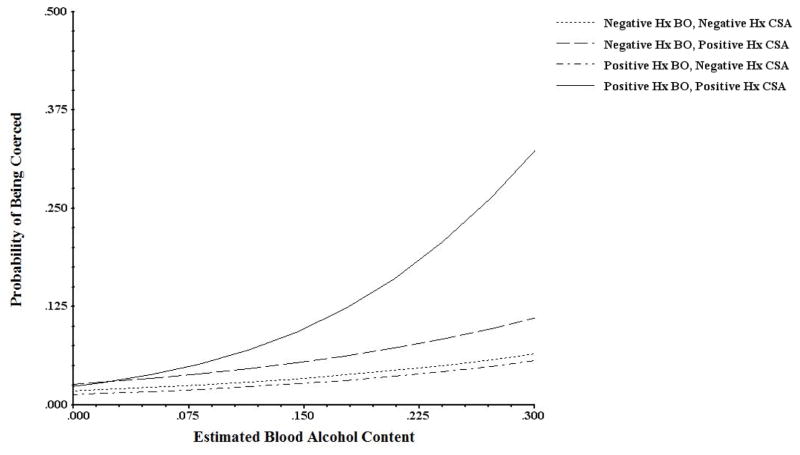

Interestingly, the slope of victimization on event-level eBAC was moderated by history of blackout (B = 0.016, OR = 1.016, 95 CI = 1.006, 1.027). Specifically, a .01 g/dL increase in eBAC was associated with a 4.4% increase in the likelihood of sexual coercion victimization for individuals without a history of blackouts, but a 6.0% increase for individuals with a prior history of alcohol-induced blackouts. We did not observe any moderating effect of gender or history of CSA on the association between event-level eBAC and victimization. However, we did observe a significant event-level eBAC × history of blackout × gender interaction (B = −0.032, OR = 0.969, 95 CI = 0.954, 0.983) and a significant event-level eBAC × history of blackout × history of CSA interaction (B = 0.044, OR = 1.045, 95 CI = 1.003, 1.088). The effects of these three-way interactions are illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of being coerced into sexual activity as a function of increasing estimated blood alcohol content (eBAC). Here, we present the effects of three-way eBAC × blackout history × gender interaction. Results indicate that women without a history of blackouts were at greatest risk of being sexually coerced at low levels of eBAC, whereas women with a history of blackouts were at greatest risk at high levels of eBAC. Note: Hx BO = history of blackout.

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of being coerced into sexual activity as a function of increasing estimated blood alcohol content (eBAC). Here, we present the effects of three-way eBAC × blackout history × childhood sexual abuse (CSA) history interaction. Results indicate that participants with a dual history of blackouts and CSA were at greatest risk of being coerced as eBAC increased. Note: Hx BO = history of blackout, Hx CSA = history of childhood sexual abuse.

Associations between Alcohol, Blackouts, CSA, and Perpetration

Results of the perpetration model are again summarized in Table 2. In examining sexual coercion perpetration, our analyses indicated main effects of male gender (B = 0.045, OR = 1.046, 95% CI = 1.000, 1.094) and history of CSA (B = 0.133, OR = 1.142, 95% CI = 1.053, 1.239) on the intercept, suggesting that these variables confer a greater overall risk for perpetration. A history of blackout was not associated with a greater likelihood of sexual coercion perpetration. However, we did observe a significant history of blackout × gender interaction effect on the intercept (B = −0.578, OR = 0.561, 95% CI = 0.453, 0.694), which indicated that men without a history of alcohol-related blackouts were generally more likely to be perpetrators than men with a history of blackouts. We also observed a significant history of blackout × history of CSA interaction effect on the intercept (B = 1.167, OR = 3.213, 95% CI = 2.577, 4.006), suggesting that participants with a dual history of blackout and CSA were most likely to be perpetrators.

Our analyses also indicated that the likelihood to perpetrate increased as a function of event-level eBAC (B = 0.034, OR = 1.035, 95% CI = 1.032, 1.038), year-level average eBAC (B = 0.009, OR = 1.009, 95% CI = 1.004, 1.013), and total average eBAC (B = 0.018, OR = 1.018, 95% CI = 1.014, 1.023). The association between event-level eBAC and perpetration was moderated by gender (B = 0.018, OR = 1.018, 95% CI = 1.011, 1.024), such that risk for perpetration was significantly greater for men than women. That is, a .01 g/dL increase in eBAC was associated with a 5.2% increase in the likelihood for men to perpetrate while the same increase in eBAC was associated with a 3.4% increase in the likelihood for women to perpetrate (see Figure 3). Neither history of blackout nor history of CSA moderated the association between event-level eBAC and the likelihood of sexual coercion perpetration; however, we did observe a significant event-level eBAC × history of blackout × history of CSA interaction (B = −0.037, OR = 0.964, 95% CI = 0.953, 0.975). Here, our results indicated that participants with a dual history of blackout and CSA were at greatest risk for sexual coercion perpetration at most levels of observed eBAC. However, participants with a history of CSA and no history of blackout were the most likely to perpetrate at high levels of eBAC. The effect of this three-way interaction is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Predicted probability of coercing others into sexual activity as a function of increasing estimated blood alcohol content (eBAC). Here, we present the effects of an eBAC × gender interaction. Results indicate that male participants were more likely to coerce others into sexual activity as eBAC increased.

Figure 4.

Predicted probability of coercing others into sexual activity as a function of increasing estimated blood alcohol content (eBAC). Here, we present the effects of three-way eBAC × blackout history × childhood sexual abuse (CSA) history interaction. Results indicate that participants with a dual history of blackout and CSA were at greatest risk for coercing others into sexual activity at most levels of observed eBAC. Note: Hx BO = history of blackout, Hx CSA = history of childhood sexual abuse.

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to use a daily monitoring approach to examine the within-person effect of alcohol intoxication on sexual coercion victimization and perpetration, as well as the moderating effects of history of blackouts and CSA. Our hypotheses were partially supported as higher levels of intoxication and having a history of CSA were associated with increased odds of sexual coercion victimization. Further, there was a significant three-way interaction between level of intoxication, history of CSA, and history of blackouts on victimization, such that when these variables were combined they contributed to increased odds of victimization. For sexual coercion perpetration, we found that level of intoxication, history of CSA, but not history of blackouts conferred greater odds of perpetration. Additionally, we found a complex three-way interaction between level of intoxication, history of CSA, and history of blackout. Overall, our findings supported an event-level association between level of intoxication and both sexual coercion victimization and perpetration, associations that were also moderated by CSA and alcohol-related blackouts.

Risk Factors for Sexual Victimization

With regard to victimization, our findings corroborated myriad of studies that have demonstrated an association between CSA and revictimization in adulthood (Fergusson et al., 1997), and extended this research by examining how other alcohol-related moderators influence this association. Interestingly, we found that a history of CSA did not moderate the association between level of intoxication and sexual coercion victimization; however, we did observe a three-way interaction between history of CSA, history of alcohol-related blackouts, and level of intoxication. Although individuals who experienced CSA were generally at greater risk of sexual coercion victimization, this risk was not potentiated by alcohol consumption unless that individual also had a history of blackouts, as measured during four waves of the longitudinal survey data. Based on our findings, however, it is plausible that individuals with a dual history of CSA and blackouts engage in a hazardous style of drinking that puts them at greater risk of revictimization. Specifically, there may also be a connection between CSA and alcohol-related blackouts. Indeed, research suggests that individuals with a history of childhood or adolescent sexual abuse may use heavy drinking as a dissociative coping strategy (Klanecky, McChargue, & Bruggeman, 2012) and are more likely to report blackouts (Klanecky, Harrington, & McChargue, 2008). Our preliminary finding should be investigated in additional event-level studies that ask about alcohol-related blackouts that occurred on the same day as the episode of sexual victimization.

Our results supported previous research that indicates heavy alcohol consumption is associated with greater risk for sexual victimization (Flack et al., 2007). More specifically, our results indicated that this risk is greater for individuals with a history of blackouts. In the present study, a .01 g/dL increase in eBAC was associated with a 4.4% increase in the likelihood of sexual coercion victimization for individuals without a history of blackouts, whereas the same increase in eBAC was associated with a 6.0% increase among individuals with a history of blackout. These results add to the extant literature that highlights alcohol-related blackouts as independent risk factors, above and beyond quantity of alcohol consumed, for negative consequences (e.g., Hingson et al., 2016; Wilhite & Fromme, 2015). Blackouts typically occur as the result of a particular hazardous drinking style, which can include taking shots of liquor, pre-gaming (i.e., drinking prior to an event or activity), and drinking games (LaBrie, Hummer, Kenney, Lac, & Pederson, 2011). A risky drinking style, including participating in drinking games, is also associated with sexual victimization (Johnson, Wendel, & Hamilton, 1998). Thus, a method of drinking that involves the rapid consumption of alcohol in a short period of time may serve as a shared risk factor for alcohol-related blackouts and sexual victimization.

It is important to note that we did not measure whether a blackout occurred during victimization (or perpetration). Rather, we found that a prior history of alcohol-related blackouts was associated with a greater likelihood of sexual coercion victimization, and this risk was greatest among women and participants with a history of CSA. Future research should aim to examine the event-level association between alcohol-related memory loss and sexual victimization and examine specific mechanisms that might mediate this association (e.g., inability to form memories of sexual risk). Laboratory studies involving alcohol administration might measure how these between person factors influence the perception of sexually coercive situations when the individual is intoxicated. Further studies using ecological momentary assessment might be a particularly enlightening way to assess alcohol-related blackouts and their influence on sexual victimization as these events are unfolding.

Risk Factors for Perpetration of Non-consensual Sexual Activity

With regard to perpetration, our findings coalesce with previous research that has reported an association between history of CSA and perpetration of sexual assault (e.g., Casey et al., 2017). Here, we found that men were at greater risk of sexual coercion perpetration, which corroborates large, cross-sectional studies that have similarly found that males are more likely to be sexual perpetrators (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2013). Importantly, not all of the instances of sexual coercion perpetration were committed by men, highlighting the importance of including all genders in research on sexual perpetration among college students.

Interestingly, our results indicated that participants with a dual history of CSA and alcohol-related blackouts were generally the most likely to be perpetrators of sexual coercion, but this effect varied as a function of eBAC. Specifically, at higher levels of intoxication (e.g., eBAC > 0.250), individuals with a history of CSA but without a history of blackouts were most likely to perpetrate. Perpetrators with a history of CSA may drink at excessive levels to cope with the emotional repercussions of their past trauma (Goldstein, Flett, & Wekerle, 2010). Further, although unexpected, one plausible explanation for our findings is that the tendency to blackout while drinking may prevent a perpetrator from recalling that he or she coerced someone into sexual activity. Thus, at higher levels of intoxication, when blackouts are more likely to occur (Hartzler & Fromme, 2003), perpetrators with a history of blackouts may not remember perpetrating the previous day. Conversely, those who had higher levels of intoxication but were not prone to experiencing alcohol-related blackouts would likely remember being a perpetrator and thus be more likely to report these episodes. We did not find the same complex effect of CSA and blackouts on victimization, as there may be physical evidence of sexual victimization for victims (e.g., discomfort; bleeding), even after an episode of alcohol-related memory loss, that would not be apparent for perpetrators. The three-way interactions were largely exploratory and additional research whereby both parties report on a given incident could facilitate our understanding of the role of memory loss in sexual coercion perpetration.

Conclusions

The present study provided further support for the need to address specific risk factors for sexual victimization and perpetration when designing prevention and intervention initiatives for college students. Although we chose to examine coerced sexual victimization and perpetration, it is important to emphasize that sexual victimization need not involve coercion. For example, having sex with an individual who is incapacitated from alcohol may not involve any coercion, but is clearly sexual assault/victimization. Despite the recent empirical support for the inclusion of blackout-relevant information in prevention and intervention modules (Wetherill & Fromme, 2016), only one study has examined how a motivational interviewing intervention contributed to fewer blackouts at follow up (Kazemi, Levine, Dmochowski, Nies, & Sun, 2013). Our results speak to augmenting current prevention modules (e.g., Alcohol Edu) to include both precursors of blackouts (e.g., chugging drinks, drinking games) and negative consequences, such as sexual victimization and perpetration, that are exacerbated by blackouts. Particularly relevant to these findings, prevention modules and motivational interventions should specifically mention that individuals predisposed to blackouts may be at greater risk of victimization when drinking—especially if they are female or have a history of CSA. In an effort to prevent these tragic outcomes, students could receive information about protective behavioral strategies designed to specifically decrease the likelihood of a blackout by reducing the rate of increase in BAC as well as the overall level of intoxication, including avoiding pre-gaming and drinking shots of liquor (Treloar, Martens, & McCarthy, 2015). Bystander interventions could also highlight the importance of noticing when individuals are engaging in behaviors known to increase blackouts, and intervene to thereby decrease the risk for sexual victimization. Finally, including items about blackouts on screening questionnaires at university health centers could serve as a valuable tool whereby medical professionals could provide brief interventions that highlight the risk of blackouts for sexual victimization and perpetration among at-risk college students (Hingson et al., 2016).

Although the present study was a large, ecologically valid examination of victimization and perpetration of sexual coercion, results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, blackouts were not assessed during the daily monitoring surveys, which means we are not able to determine whether a blackout occurred during the incident of victimization or perpetration. Second, as an item from the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index, the blackout measure assessed whether someone “woke up in a place where they did not remember getting to” during the past three months, which does not capture all types of alcohol-related blackout experiences, and may have resulted in an underestimate of those with a history of blackouts. Third, this study assessed daily covariation between alcohol consumption and victimization/perpetration, so we are unable to comment on specific temporal linkages between the two variables. Fourth, daily surveys were administered the morning after the drinking event, which should minimize problems with distal recall, but perhaps less so if the previous day involved heavy drinking or an alcohol-related blackout. Fifth, we did not define “coercion” or the particular type of “sexual activities” in our daily surveys. Consequently, our rates of victimization and perpetration may differ from previous studies that have examined more discrete forms of sexual victimization. Sixth, the majority of the sample was White and all were college students, which means the results may not generalize to other populations. Finally, our sample consisted of a higher proportion of women than the overall University enrollment (“Accountability and Performance Report,” 2005). Nevertheless, the longitudinal event-level design of the present study is a considerable strength, as we were able to follow the same individuals over many years and accurately characterize critical factors that confer risk for victimization and perpetration of sexual coercion

The present study indicated that alcohol use, blackouts, and CSA are potent risk factors for victimization and perpetration of sexual coercion. Moreover, our analyses yield novel insight into how these factors interact to confer risk during college. Overall, our findings emphasize the effects of hazardous drinking and blackouts on sexual victimization and perpetration, and further substantiate the urgent need to develop effective intervention and prevention efforts to decrease the incidence of sexual assault on college campuses.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grants R01-AA013967, R01-AA020637, and 5T32-AA07471 and the Waggoner Center for Alcohol and Addiction Research.

References

- Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: a common problem among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(s14):118–128. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, Clinton AM, Buck PO. Attitudinal, experiential, and situational predictors of sexual assault perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16(8):784–807. doi: 10.1177/088626001016008004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Wegner R, Woerner J, Pegram SE, Pierce J. Review of survey and experimental research that examines the relationship between alcohol consumption and men’s sexual aggression perpetration. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2014;15(4):265–282. doi: 10.1177/1524838014521031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: what do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9(3):271–303. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashenhurst JR, Harden KP, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Trajectories of binge drinking and personality change across emerging adulthood. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2015;29(4):978–991. doi: 10.1037/adb0000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Universities. Report on the AAU Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct. Retrieved from https://www.aau.edu/uploadedFiles/AAU_Publications/AAU_Reports/Sexual_Assault_Campus_Survey/AAU_Campus_Climate_Survey_12_14_15.pdf.

- Bryan AEB, Norris J, Abdallah DA, Stappenbeck CA, Morrison DM, Davis KC, … Zawacki T. Longitudinal change in women’s sexual victimization experiences as a function of alcohol consumption and sexual victimization history: A latent transition analysis. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6(2):271–279. doi: 10.1037/a0039411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae HC, Hong S, Jang SI, Lee KS, Park EC. Patterns of alcohol consumption and suicidal behavior: Findings from the fourth and fifth Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2007–2011) Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2015;48(3):142–150. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.14.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breiding MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking, and intimate partner violence victimization—National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey, United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries (Washington, D.C.: 2002) 2014;63(8):1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelow G, Koeppel J. Psychological consequences of alcohol induced blackout among college students. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1995;40(3):10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Casey EA, Masters NT, Beadnell B, Hoppe MJ, Morrison DM, Wells EA. Predicting sexual assault perpetration among heterosexually active young men. Violence Against Women. 2017;23(1):3–27. doi: 10.1177/1077801216634467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Iwamoto DK, Fromme K. A comprehensive longitudinal test of the acquired preparedness model for alcohol use and related problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:602–610. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviors and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21(8):789–803. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack WF, Daubman KA, Caron ML, Asadorian JA, D’Aureli NR, Gigliotti SN, … Stine ER. Risk factors and consequences of unwanted sex among university students hooking up, alcohol, and stress response. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22(2):139–157. doi: 10.1177/0886260506295354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Follette VM, Polusny MA, Bechtle AE, Naugle AE. Cumulative trauma: The impact of child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and spouse abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress. n.d;9(1):25–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02116831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(5):1497–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gámez-Guadix M, Straus MA, Hershberger SL. Childhood and adolescent victimization and perpetration of sexual coercion by male and female university students. Deviant Behavior. 2011;32(8):712–742. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Flett GL, Wekerle C. Child maltreatment, alcohol use and drinking consequences among male and female college students: An examination of drinking motives as mediators. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(6):636–639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Barthel JM, Taylor S. Sex and drugs and starting school: Differences in precollege alcohol-related sexual risk taking by gender and recent blackout activity. The Journal of Sex Research. 2017;54(6):741–751. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1228797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzler B, Fromme K. Fragmentary and en bloc blackouts: Similarity and distinction among episodes of alcohol-induced memory loss. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2003;64(4):547–550. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Zha W, Simons-Morton B, White A. Alcohol-induced blackouts as predictors of other drinking related harms among emerging young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(4):776–784. doi: 10.1111/acer.13010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE, Griffin MA, Boekeloo BO. Prevalence and psychosocial correlates of alcohol-related sexual assault among university students. Adolescence. 2008;43(172):733–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Carey KB. Using calculations to estimate blood alcohol concentrations for naturally occurring drinking episodes: a validity study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(1):130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennison KM, Johnson KA. Drinking-induced blackouts among young adults: Results from a national longitudinal study. Substance Use & Misuse. 1994;29(1):23–51. doi: 10.3109/10826089409047367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi DM, Levine MJ, Dmochowski J, Nies MA, Sun L. Effects of motivational interviewing intervention on blackouts among college freshmen. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2013;45(3):221–229. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klanecky AK, Harrington J, McChargue DE. Child sexual abuse, dissociation, and alcohol: Implications of chemical dissociation via blackouts among college women. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(3):277–284. doi: 10.1080/00952990802013441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klanecky A, McChargue DE, Bruggeman L. Desire to dissociate: Implications for problematic drinking in college students with childhood or adolescent sexual abuse exposure: Desire to dissociate. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21(3):250–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Heilig M, Cunningham CL, Stephens DN, Duka T, Malley SSO. Ethanol consumption: How should we measure it? Achieving consilience between human and animal ohenotypes. Addiction Biology. 2010;15(2):109–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh C, Gidycz CA. A prospective analysis of the relationship between childhood sexual victimization and perpetration of dating violence and sexual assault in adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21(6):732–749. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: Two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;4(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Brown AL. Child maltreatment and perceived family environment as risk factors for adult rape: is child sexual abuse the most salient experience? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(10):1019–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Coates AA, Gaffey KJ, Johnson CF. Sexuality, substance use, and susceptibility to victimization risk for rape and sexual coercion in a prospective study of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(12):1730–1746. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt MP, Zakletskaia LI, Brown DD, Fleming MF. Alcohol-induced memory blackouts as an indicator of injury risk among college drinkers. Injury Prevention. 2012;18(1):44–49. doi: 10.1136/ip.2011.031724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Carey KB. Association between alcohol intoxication and alcohol-related problems: An event-level analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(2):194–204. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Fromme K. Event-level covariation of alcohol intoxication and behavioral risks during the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75(2):294–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Predictors and outcomes of variability in subjective alcohol intoxication among college students: An event-level analysis across 4 years. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(3):484–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Fromme K. Event-level associations between objective and subjective alcohol intoxication and driving after drinking across the college years. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):384–392. doi: 10.1037/a0024275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PD, Stappenbeck CA, Fromme K. An event-level examination of sex differences and subjective intoxication in alcohol-related aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;21(2):93–102. doi: 10.1037/a0031552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. SAGE; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Romano E, Luca RVD. Exploring the Relationship Between Childhood Sexual Abuse and Adult Sexual Perpetration. Journal of Family Violence. 1997;12(1):85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Childhood and adolescent sexual abuse and subsequent sexual risk behavior: Evidence from controlled studies, methodological critique, and suggestions for research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(5):711–735. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Cleveland MJ. Does alcohol contribute to college men’s sexual assault perpetration? Between-and within-person effects over five semesters. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2017;78:5–13. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Parks KA, Hoffman JH, Crane CA, Leonard KE, Shyhalla K. Do drinking episodes contribute to sexual aggression perpetration in college men? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76(4):507–515. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp AT, DeGue S, Valle LA, Brookmeyer KA, Massetti GM, Matjasko JL. A systematic qualitative review of risk and protective factors for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2013;14(2):133–167. doi: 10.1177/1524838012470031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MP, Swartout KM, Koss MP. Trajectories and predictors of sexually aggressive behaviors during emerging adulthood. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3(3):247–259. doi: 10.1037/a0030624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treloar H, Martens MP, McCarthy DM. The protective behavioral strategies Scale–20: Improved content validity of the serious harm reduction subscale. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27(1):340–346. doi: 10.1037/pas0000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Karabatsos G, Koss MP. Alcohol and sexual assault in a national sample of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14(6):603–625. [Google Scholar]

- Valenstein-Mah H, Larimer M, Zoellner L, Kaysen D. Blackout drinking predicts sexual revictimization in a college sample of binge-drinking women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2015;28(5):484–488. doi: 10.1002/jts.22042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill RR, Castro N, Squeglia LM, Tapert SF. Atypical neural activity during inhibitory processing in substance-naïve youth who later experience alcohol-induced blackouts. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;128(3):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill RR, Fromme K. Alcohol-induced blackouts: A review of recent clinical research with practical implications and recommendations for future studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(5):922–935. doi: 10.1111/acer.13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM. What happened? alcohol, memory blackouts, and the brain. Alcohol Research & Health. 2003;27(2):186–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Jamieson-Drake DW, Swartzwelder HS. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol-induced blackouts among college students: Results of an e-mail survey. Journal of American College Health. 2002;51(3):117–131. doi: 10.1080/07448480209596339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Signer ML, Kraus CL, Swartzwelder HS. Experiential aspects of alcohol-induced blackouts among college students. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30(1):205–224. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 1989;50(01):30. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhite ER, Fromme K. Alcohol-induced blackouts and other negative outcomes during the transition out of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76(4):516–524. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Mitchell KJ. Prevalence rates of male and female sexual violence perpetrators in a national sample of adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(12):1125–1134. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawacki T, Abbey A, Buck PO, McAuslan P, Clinton-Sherrod AM. Perpetrators of alcohol-involved sexual assaults: How do they differ from other sexual assault perpetrators and nonperpetrators? Aggressive Behavior. 2003;29(4):366–380. doi: 10.1002/ab.10076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]