Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases represent a major cause of death and morbidity. Cardiac and vascular pathologies develop predominantly in the aged population in part due to lifelong exposure to numerous risk factors but are also found in children and during adolescence. In comparison to adults, much has to be learned about the molecular pathways driving cardiovascular diseases in the pediatric population. Sirtuins are highly conserved enzymes that play pivotal roles in ensuring cardiac homeostasis under physiological and stress conditions. In this review, we discuss novel findings about the biological functions of these molecules in the cardiovascular system and their possible involvement in pediatric cardiovascular diseases.

Keywords: Sirtuins, Heart, Pediatric cardiology, CHD

Sirtuins: Biological Functions

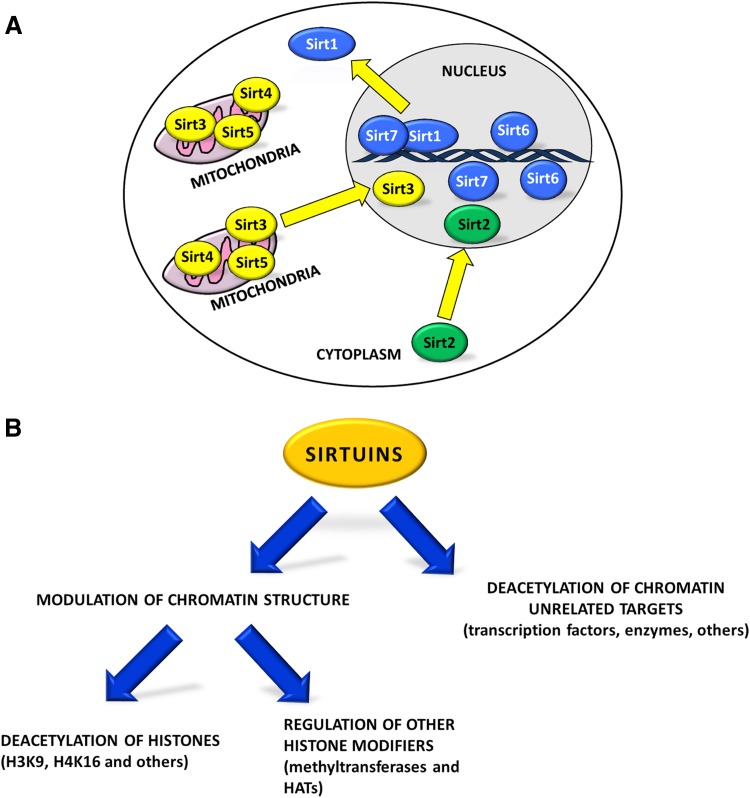

Sirtuins constitute a class of highly conserved enzymes, which act preferentially as NAD+-dependent deacetylases and/or mono-ADP-ribosyl transferases. In addition, some sirtuins exhibit less characterized enzymatic activities such as desuccinylation, glycohydrolase, and demalonylation [1–5]. In mammals, sirtuins comprise a family of seven members (Sirt1-Sirt7; Fig. 1a). Mammalian sirtuins share a conserved catalytic domain but possess different N-terminal and C-terminal sequences, which are unique for each member of the family and are important for their subcellular localization and isoform-specific functions [1, 6]. Sirt1, Sirt6, and Sirt7 are mainly present in the nucleus; Sirt2 primarily resides in the cytoplasm while Sirt3, Sirt4, and Sirt5 are mitochondrial enzymes [7]. Despite their preferential localization, sirtuins can shuttle between different cellular compartments in response to internal or external cues [8–11]. Mammalian sirtuins are implicated in numerous biological processes such as cellular differentiation, metabolism, cancer progression, apoptosis, maintenance of genomic stability and aging. In yeast, sirtuins promote the extension of life span while in mammals they mediate the beneficial and anti-aging effects of physical exercise and caloric restriction [12].

Fig. 1.

Subcellular localization and function of sirtuins. a Subcellular localization of the seven mammalian sirtuins. Sirt1, Sirt6, and Sirt7 are mainly localized in the nucleus. Sirt2 is a cytoplasmic enzyme while Sirt3, Sirt4, and Sirt5 are enriched in mitochondria [7]. In response to internal and external stimuli, sirtuins can translocate into other cellular compartments (yellow arrows) regulating a vast number of biological functions [8–11]. b Sirtuins control chromatin dynamics either by directly deacetylating histones such as histone 3 at lysine 9 (H3K9) and lysine 16 of histone 4 (H4K16) or through regulation of other histone modifiers such as methyltransferases and histone acetyltransferases (HATs). In addition, sirtuins regulate, mainly through direct deacetylation, several other targets such as transcription factors and enzymes [18]

Sirtuins have been recognized as pivotal regulators of cellular stress responses [13]. In response to a broad range of stress stimuli, they contribute to the adaptation of cellular physiology to harsh and varying conditions ensuring the maintenance of cellular homeostasis [14]. Stress stimuli promptly regulate expression of sirtuins and modulate their activation mainly by controlling their post-translational modification [15–17]. Sirtuins act mainly via two different mechanisms: (i) they promote heterochromatin formation at different chromosomal loci. This is achieved either by direct deacetylation of histones or by modulation of the activity and/or the recruitment of other histone modifiers such as acetyltransferases and methyltransferases [18]; (ii) sirtuins control numerous chromatin unrelated targets mainly via direct deacetylation. These targets mostly comprise enzymes and transcription factors such as p53, FOXO, MyoD, and NF-κB. In some cases, the same molecular targets are addressed by different sirtuins [18] (Fig. 1b). Finally, recent studies demonstrated the presence of a mutual regulation between different members of mammalian sirtuins, indicating that these molecules are part of a highly complex molecular network that maintains cellular homeostasis [19–22].

Sirt1 in the Development of Cardiovascular System: Role in Congenital Heart Defects

Congenital heart diseases (CHDs) represent the most common category of birth defects with a prevalence of around 1% in the global population. Recent advances in the early diagnosis, corrective surgery, and post-operatory care have significantly reduced mortality in affected children, substantially increasing the percentage of patients surviving into adulthood [23]. Although several genetic aberrations have been associated with CHDs, the majority of cases does not depend on monogenetic causes [24]. Certain maternal conditions such as diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and exposure to toxic substances have been recognized as risk factors associated with CHDs [24]. The molecular pathways that underlie the development of pathological cardiovascular conditions during pregnancy and after birth as well as the influence of environmental factors are still not well understood.

Growing experimental evidence supports an important role of Sirt1 in the development of cardiovascular system. Sirt1 is highly expressed in the embryonic heart but its expression dramatically declines in adult animals [10]. Sirt1 constitutive knockout animals show congenital cardiac abnormalities and die mostly before the age of 2 weeks after birth (Table 1) [25, 26]. Recently, we uncovered a novel role of Sirt1 in the regulation of cardiac progenitor cell (CPC) proliferation and specification in dependence on oxygen availability (Fig. 2). Although hypoxia was described as a risk factor for CHD, the molecular mechanisms remained largely unknown [26]. We discovered that during early stages of heart morphogenesis spatial and temporal differences in oxygen concentration determine expression of the critical transcription factors, ISL1 and NKX2.5, thereby regulating CPCs proliferation and specification. Moreover, we have demonstrated that Sirt1 is a critical factor, which translates differences in oxygen concentration into transcriptional responses [26].

Table 1.

Role of sirtuins in the cardiovascular system

| Sirtuin | Cardiac phenotype in mouse models under basal conditions | Role in response to stress stimuli | Gene alterations associated with cardiovascular diseases in humans |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sirt1 | • Congenital heart abnormalities in constitutive KO mice [25, 26] • Conductive disturbances, insulin resistance and cardiac hypertrophy in cardiac-specific KO mice [31, 44] • Low to moderate expression in Tg-mice inhibits age-dependent cardiac remodeling [53] |

• Cardiomyocytes survival [45–50] | • SNPs at the Sirt1 promoter associate with ventricular septal defects [33] • SNPs correlate with acute myocardial infarction [88] |

|

Adverse effects

• Cardiac abnormalities in response to maternal exposure to hypoxia [26] • Promotes mitochondrial dysfunctions in failing hearts [52] • Promotes cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload [51] | |||

|

Adverse effects

• High levels of expression in Tg-mice promote age-dependent fibrosis and hypertrophy [53] | |||

| Sirt2 | • Increased age-dependent cardiac remodeling in constitutive KO mice [54] | • Inhibition of hypertrophy [54] | • SNPs correlate with acute myocardial infarction [87] |

| Sirt3 | • Increased cardiac remodeling in constitutive KO mice [60, 63, 64] | • Inhibition of cardiac remodeling and maintenance of mitochondrial functions [60–68] | • SNPs correlate with acute myocardial infarction [89] • SNPs correlate with PAH [101] |

| Sirt4 | • No obvious phenotype in constitutive KO mice [69] |

Adverse effects

• Promotes pathological cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload [69] |

Not reported |

| Sirt5 | • Increased cardiac remodeling in constitutive KO mice [70] | • Maintains mitochondrial functionality and prevents adverse remodeling [71, 72] | Not reported |

| Sirt6 | • Increased cardiac remodeling in constitutive KO mice [73] | • Inhibits pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic pathways [73–82] | • SNPs correlate with acute myocardial infarction [90] |

| Sirt7 | • Age-dependent cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy [83, 84] |

Adverse effects

• Prevents fibrosis and scar formation in response to ischemia reperfusion injury [85] |

Not reported |

The table summarizes the major roles of sirtuins in the heart under basal conditions or in response to exposure to stress stimuli. The table also reports known alterations of sirtuin genes, which correlate with cardiac diseases in human patients (Tg-mice transgenic mice, SNPs single-nucleotide polymorphisms, KO knock-out, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension) [25, 26, 31, 33, 44–54, 60–85, 87–90, 101]

Fig. 2.

Sirt1 regulates proliferation and differentiation of CPCs in the SHF under physiological conditions and instigates aberrant cardiogenesis in response to hypoxia. In CPCs of the SHF (yellow), ISL1 recruits histone deacetylases (HDACs) to the promoter of the Nkx2.5 gene, inhibiting its expression and thereby promoting ISL1+ cells expansion. As ISL1+ cells incorporate into the hypoxic heart tube, Sirt1 stimulates the commitment of these cells toward the cardiomyocyte lineage (blue) by forming a molecular complex with HIF1α and the transcription factor HES1 at the Isl1 gene promoter thereby epigenetically inhibiting Isl1 expression. This process promotes Nkx2.5 expression and cardiomyocyte differentiation. Pathological exposure to hypoxia promotes formation of a HIF1α/Sirt1/Hes1 complex at the Isl1 promoter leading to the premature specification of CPCs, causing congenital heart defects [26]

The heart is built from cells either located in the first heart field (FHF) or the second heart field (SHF) [27, 28]. The FHF forms the primary heart tube and parts of the left ventricle, whereas CPCs from the SHF contribute to the atria, the right ventricle, and the venous and anterior pole of the heart [29, 30]. After expression in cells that give rise to both the FHF and SHF, ISL1 is primarily found in CPCs of the SHF, where it is involved in the regulation of cellular proliferation. NKX2.5 does not show a heart field-specific expression but seems to be expressed at later stages of cardiomyogenic differentiation when CPCs start to turn off the expression of ISL1 and are acquiring a more mature cardiomyocyte phenotype [29, 30]. In the SHF, ISL1 inhibits premature differentiation of CPCs by recruiting histone deacetylases (HDACs) to the Nkx2.5 promoter, leading thereby to inhibition of NKX2.5 expression. This process permits expansion of ISL1+ cells [26]. Interestingly, the particular niche where ISL1+ cells reside maintains relatively high oxygen concentration. In contrast, regions of the developing heart tube, where NKX2.5 activity leads to CPCs specification and subsequent differentiation into cardiomyocytes, are hypoxic (Fig. 2). In the forming heart, the reduced oxygen concentration triggers recruitment of the hypoxia inducible factor HIF1α to the Isl1 promoter. HIF1α then attracts the transcription factor HES1 and Sirt1, resulting in Sirt1-mediated epigenetic silencing of ISL1 expression. At the same time, the inhibitory effect of ISL1 on the Nkx2.5 promoter is relieved, NKX2.5 expression increases, thereby ensuring commitment of CPCs to the cardiomyocyte lineage [26, 29]. We have further demonstrated that the exposition of female mice to pathological hypoxia leads to precocious specification of ISL1+ cells in developing embryos due to aberrant recruitment of SIRT1 to the Isl1 promoter and inactivation of Isl1 expression. As a consequence of expression changes induced by exposure to the pathological hypoxia, the pools of proliferating and committed CPCs are abated and congenital heart defects develop (Fig. 2). Inactivation of Sirt1 specifically in ISL1+ cells of the SHF is able to avert the negative effects of pathological hypoxia during heart development, preventing the onset of cardiac abnormalities [26]. Interestingly, inactivation of Sirt1 in ISL1+ cells under physiological conditions does not result in major cardiac abnormalities, although Isl1 expression is promoted and Nkx2.5 expression is decreased, indicating that under physiological conditions still unknown mechanisms compensate for Sirt1 deficiency in the SHF [26].

Another important function of Sirt1 in cardiac physiology is the regulation of cardiac electrical activity. Sirt1-dependent deacetylation of the voltage-gated Na+ channel, Nav1.5, at lysine 1479 is a prerequisite for its correct localization in the cell membrane. Cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of Sirt1 in mice causes cardiac conductive abnormalities and premature death due to arrhythmia (Table 1) [31]. Interestingly, mutations in the SCN5A gene coding for NAv1.5 have been found in patients suffering from arrhythmia disorders such as the long-QT and the Brugada syndrome and other inherited conduction diseases [32]. Such arrhythmias often affect pediatric patients and underlie many causes of sudden death in pediatric population.

Taken together, there is strong experimental evidence that Sirt1 is important for proper heart development and maintenance of cardiac functions. Therefore, changes in Sirt1 expression and/or activity may be associated with the development of CHDs. At this point, it is worth noting that an occurrence of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) at the Sirt1 promoter, which might alter Sirt1 expression, was found in human subjects with ventricular septal defects (Table 1) [33]. Furthermore, reduction of the activity and/or expression of Sirt1 and Sirt3 in different fetal tissues has been described in maternal conditions favoring occurrence of congenital heart diseases, such as gestational diabetes and obesity [34–37]. Moreover, mutations in genes encoding enzymes from the NAD biosynthesis pathway have been associated with congenital heart malformations [38]. Since NAD is a fundamental co-enzyme required for sirtuin activity, it is reasonable to assume that any disturbances in NAD availability might inhibit sirtuin activity and result in a cardiac phenotype.

Role of Sirtuins in Cardiac Stress Responses

The heart is a very dynamic organ that can adapt its function in response to different physiological and pathological stimuli. During adaption, the heart activates a complex network of metabolic and molecular changes that enable cardiac remodeling [39]. Cardiac remodeling occurs under physiological conditions such as physical exercise or changes in metabolism. In response to persistent stress, however, cardiac remodeling may promote deterioration of ventricular function leading to heart failure. Adverse cardiac remodeling processes comprise cardiomyocytes hypertrophy or death, myocardial fibrosis and inflammation [40, 41]. Mitochondria not only play a pivotal role in the maintenance of cardiac functions by providing energy but also contribute to oxidative stress. Mitochondrial dysfunction is an important event that contributes to cardiac remodeling and heart failure as a consequence of prolonged exposure of the heart to challenging stimuli [42]. Several other molecular pathways are associated with adverse cardiac remodeling. For instance, the differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts into myofibroblasts is a crucial event that leads to cardiac fibrosis further compromising heart contractility and contributing to heart failure [43].

Sirtuins have been shown to contribute to homeostasis of the heart under physiological and stress conditions by controlling a vast number of molecular pathways. Sirt1 promotes the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis by activating key transcription factors involved in biogenesis of mitochondria. Consequently, mitochondrial biogenesis and function are impaired in hearts of cardiac-specific Sirt1 knockout mice. Altogether, inactivation of Sirt1 in cardiomyocytes led to symptoms characteristic for diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) including cardiac hypertrophy, abnormal glucose metabolism and insulin resistance. Importantly, treatment of DCM mice with a Sirt1 activator, resveratrol, reverses the DCM phenotype [44]. Several further investigations reported protective effects of Sirt1 in the heart, especially under stress conditions. Generally, Sirt1 lowers oxidative stress and favors cardiomyocytes survival [45–50]. Surprisingly, however, it was observed that Sirt1 KO mice were protected from cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload [51]. Furthermore, Sirt1 is upregulated in failing hearts where it promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and heart failure [52]. These controversial findings suggest that Sirt1 might exert protective or deleterious effects in the heart probably depending on the type of stress that dominates. In addition, the influence of Sirt1 on cardiac physiology appears to be dosage-dependent. In fact, high levels of Sirt1 (more than 12 times above the normal level) have detrimental effects on the cardiac function, while a low to moderate overexpression of Sirt1 in transgenic mice inhibits age-dependent development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis [53]. These data illustrate the high degree of complexity of Sirt1-dependent regulatory processes during cardiac stress responses (Table 1).

Much less is known about the role of the cytoplasmic Sirt2 in the heart. One study described a protective role of Sirt2 by preventing age-associated and stress-induced cardiac remodeling in mice through activation of anti-hypertrophic signaling pathways (Table 1) [54]. Sirt2 has been also shown to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis, protect against oxidative stress and improve insulin sensitivity in hepatocytes [55]. However, it is not known whether similar mechanisms might contribute to cardiac homeostasis.

Mitochondrial sirtuins, Sirt3, Sirt4, and Sirt5, attracted more attention than Sirt2 in the heart. Sirt3 regulates the global acetylome of mitochondrial proteins. Inactivation of Sirt3 results in a significant increase in the acetylation levels of key mitochondrial enzymes and in a specific inactivation of the mitochondrial complex I activity, suggesting that Sirt3 is an important factor maintaining basal ATP levels [56–60]. Sirt3-deficient mice show enhanced cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy, which manifest already in young animals and progress with aging. In addition, Sirt3 knockout mice display higher rate of cardiac remodeling and cardiac dysfunction in response to stress stimuli due to the impaired mitochondrial function and accumulation of oxidative stress. In contrast, Sirt3 overexpressing mice are protected against cardiac stressors [60–64]. Several other reports demonstrated an essential role for Sirt3 in cardiac protection under different stress conditions. Sirt3 overexpression in primary cardiomyocytes reduced cellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by deacetylating the transcription factor Foxo3a and thereby stimulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes-encoding genes. Through decreased ROS level and other mechanisms, Sirt3 further contributed to lower apoptosis in response to stress [63, 65–67]. Moreover, Sirt3 prevents cardiac differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and hence fibrosis in vitro [68]. In contrast to the beneficial effects of Sirt3, Sirt4 has been shown to promote pathological cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload by enhancing oxidative stress. Interestingly, Sirt4 seems to antagonize Sirt3-dependent activation of an antioxidative enzyme, the manganese dependent superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) [69]. The last mitochondrial sirtuin, Sirt5, exhibits predominantly a protective role in the heart. Sirt5 was shown to desuccinylate and activate enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation. Remarkably, the main enzyme regulated by Sirt5 in the heart is ECHA. Decreased ECHA activity was identified in the heart of Sirt5 knockout mice as a direct cause responsible for progressive cardiac dysfunction starting already in young animals and culminating in loss of ATP reservoirs and enhanced cardiac hypertrophy [70]. Two further reports demonstrated that Sirt5 protects the heart from injuries such as ischemia reperfusion and pressure overload by preserving mitochondrial function (Table 1) [71, 72].

Cardiac function is also strongly influenced by the nuclear sirtuin, Sirt6. Cardiomyocyte-specific Sirt6 KO animals develop spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy already at around 8–12 weeks of age [73]. Moreover, Sirt6 downregulation has been observed in failing human hearts and in mice exposed to hypertrophic stimuli while transgenic mice overexpressing Sirt6 were protected from hypertrophy in response to stress [73]. Sirt6 has been shown to inhibit different pro-hypertrophic pathways such as IGF-Akt, NF-κB and STAT3 and prevent oxidative stress and cardiac fibrosis through inhibition of the NF-κB and the AMPK/angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 pathways [73–81]. Furthermore, Sirt6 exerts a protective role in the heart by maintaining telomeres integrity in response to pressure overload (Table 1) [82].

Finally, Sirt7 plays a crucial role in the maintenance of heart homeostasis. Sirt7 KO mice show higher age-dependent accumulation of cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, inflammatory cardiomyopathy and cardiomyocyte apoptosis as compared with wild type littermates [83, 84]. This phenotype might derive from increased activation of hypertrophic pathways and p53 [84]. Another study revealed that Sirt7 deacetylates and activates the transcription factor GABPβ-1, a master regulator of the transcription of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes, and thus promotes proper mitochondria biogenesis [83]. The authors argue that an impaired mitochondrial function contributes to cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy observed in Sirt7 knockout mice. Notably, Sirt7 also negatively affects cardiac function: In response to cardiac injury, Sirt7 KO animals show reduced fibrosis and impaired scar formation that often results in cardiac rapture [85]. Sirt7 stimulates fibrosis by stabilizing the TGFß-receptor-1 through inhibition of autophagy [85]. Interestingly, stimulation of fibrosis takes place only in young animals after myocardial infarct induction. In old Sirt7 knockout animals, an increase in age-dependent fibrosis was observed [84]. Such functional duality may be explained by the fact that cardiac fibrosis in response to injury and during aging depends on the activation of different molecular pathways (Table 1) [85].

At this point, it should be also mentioned that sirtuins have also been extensively implicated in maintenance of endothelial cell homeostasis through inhibition of inflammation and regulation of numerous other molecular pathways. Through these mechanisms, sirtuins prevent endothelial dysfunction and development of atherosclerosis [86]. Although a comprehensive discussion of the role of sirtuins in endothelial cells is beyond the scope of this review, we would like to point out that most studies indicate a protective role of sirtuins in the vascular system. The importance of sirtuins in the cardiovascular system was additionally strengthened by the description of polymorphisms in the Sirt1, Sirt2, Sirt3, and Sirt6 promoters in patients with acute myocardial infarction [87–90].

Sirtuins: Possible Targets in Pediatric Cardiology?

Although the etiology of heart diseases might differ between children and adult patients, in certain cases, as for example adverse cardiac remodeling, the same pathological mechanisms are employed [91–93]. As described above, growing experimental evidence supports a role of Sirt1 in the development of congenital heart diseases. Still, very little is known about the role of other sirtuins in cardiac diseases during infancy. Inactivation of other members of the sirtuin family in mice leads to cardiac dysfunctions that mainly manifest with aging or in response to stress stimuli. Nevertheless, impaired activity of sirtuins might also be associated with deterioration of cardiac functions in children. Sirtuins are likely involved in metabolic diseases caused by genetic alterations of mitochondrial genes, which lead to dysfunctions of the respiratory chain. These diseases are often associated with skeletal myopathy and cardiomyopathies such as conduction defects and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [94]. Interestingly, it has been estimated that cardiomyopathy occurs in 20–40% of these patients already during childhood [95]. Since sirtuins residing in mitochondria (Sirt3, Sirt4, and Sirt5), but also nuclear sirtuins, strongly affect mitochondrial functions, they are probably also involved in the cellular responses to mitochondrial dysfunctions. Conversely, mitochondrial defects will affect the activity of sirtuins, since mitochondria constitute a major source for oxidation of NADH and mitochondrial malfunction can result in an unbalanced ratio of NAD+ and NADH.

Friedreich’s ataxia (FRDA) is an autosomal recessive early onset (mean age of onset between 10 and 15 years) disorder associated with dysfunctional assembly of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Patients manifest with different multisystem alterations and in 85% of the cases die as a consequence of heart failure [96]. In a mouse model of FRDA, it has been demonstrated that mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with reduced levels of NAD, which led to impaired Sirt3 activity [97]. Normalization of the unbalanced ratio of NAD+/NADH in FRDA mice restores cardiac function in a Sirt3-dependent fashion, suggesting that Sirt3 might constitute a possible target to ameliorate cardiac functions in FRDA patients [98]. Interestingly, hyperacetylation of mitochondrial enzymes has also been observed in other respiratory chains defects, suggesting that inactivation of Sirt3 might play a role in cardiomyopathies caused by mitochondrial dysfunctions [97]. In support of the significance of sirtuin function in mitochondria-based diseases, downregulation of the NAD+ as well as Sirt1, Sirt3, and Sirt4 levels has been described in human skin fibroblasts of patients with cytochrome c-oxidase deficiency, which also manifests with cardiac dysfunctions [99]. Currently, it is not known whether hearts of patients with cytochrome c-oxidase deficiency show reduced sirtuin activities and whether stimulation of sirtuin activities might ameliorate cardiomyopathy.

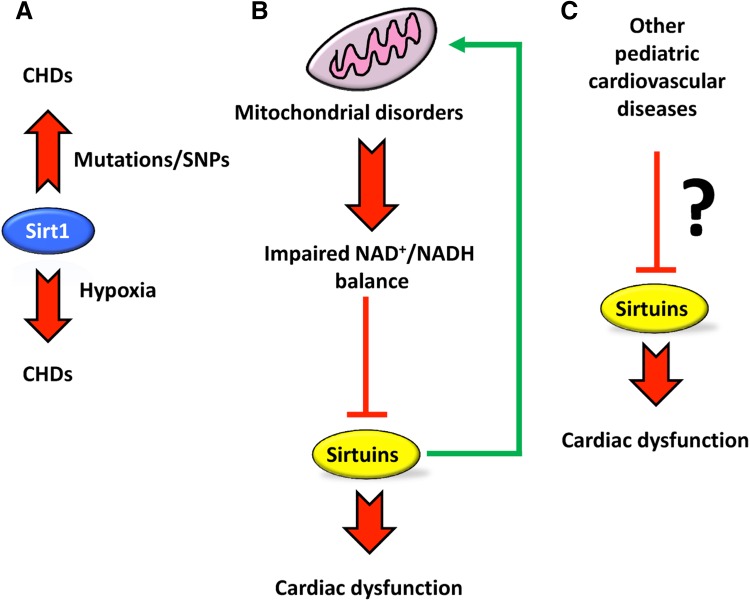

Pharmacological manipulation of sirtuins might be used to delay the onset of cardiac dysfunction in several diseases. For instance, Sirt1 activation has been shown to ameliorate cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis and restore cardiac diastolic function in dystrophic mice [100]. Furthermore, Sirt3 deficiency in mice has been associated with development of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), which causes right ventricular hypertrophy. Interestingly, a strong association of SNPs polymorphism in the Sirt3 gene, that might affect its expression or function, has been found in patients suffering from several forms of idiopathic PAH [101]. Hence, stimulation of Sirt3 activity might be seen as a potential new means to treat PAH. A scheme depicting the potential roles of different sirtuins in the pathogenesis of cardiac diseases is shown in Fig. 3 (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Possible roles of mammalian sirtuins in pediatric cardiology. a Sirt1 plays a pivotal role in normal cardiac development. Lost or reduced Sirt1 function due to mutations or SNPs may lead to congenital heart diseases (CHDs). Moreover, Sirt1 is responsible for the onset of CHDs in response to pathological exposure to hypoxia [25, 26, 31]. b Mitochondrial disorders may result in impaired NAD+/NADH ratio that can lead to inhibition of sirtuins resulting in more severe cardiac dysfunctions [97, 98]. Sirtuins can also directly improve mitochondrial functions. c Altered functions of sirtuins may contribute to accelerated deterioration of heart physiology also in other cardiac diseases, which manifest in the childhood

Conclusions

The molecular pathways that govern cardiac diseases need to be investigated more thoroughly in children and young adults. Sirtuins are important regulators of cardiac functions but their role in pediatric cardiac diseases just starts to emerge. The experimental evidence summarized in this review suggests that pharmacological manipulation of sirtuins represents an attractive option to develop new therapies that might improve heart function in children suffering from different heart diseases.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society. This work was supported by the Max Planck Society, the Excellence Initiative ‘‘Cardiopulmonary System’’ (ECCPS), the DFG collaborative research centers Pulmonary Hypertension and Core Pulmonale (Grant Number SFB1213, TP A02 and B02) and Chromatin Changes in Differentiation and Malignancy (Grant Number TRR81, TP A02) the Foundation Leducq (Grant Number 3CVD01), the German Center for Cardiovascular Research and the European Research Area Network on Cardiovascular Diseases (Grant Number CLARIFY).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Contributor Information

Alessandro Ianni, Phone: +49 (0)6032 705 1102, Email: alessandro.ianni@mpi-bn.mpg.de.

Thomas Braun, Phone: +49 (0)6032 705 1101, Email: thomas.braun@mpi-bn.mpg.de.

References

- 1.Michan S, Sinclair D. Sirtuins in mammals: insights into their biological function. Biochem J. 2007;404:1–13. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du JT, Zhou YY, Su XY, Yu JJ, Khan S, Jiang H, Kim J, Woo J, Kim JH, Choi BH, He B, Chen W, Zhang S, Cerione RA, Auwerx J, Hao Q, Lin HN. Sirt5 Is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science. 2011;334:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1207861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.French JB, Cen Y, Sauve AA. Plasmodium falciparum Sir2 is an NAD(+)-dependent deacetylase and an acetyllysine-dependent and acetyllysine-independent NAD(+) glycohydrolase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10227–10239. doi: 10.1021/bi800767t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L, Shi L, Yang S, Yan R, Zhang D, Yang J, He L, Li W, Yi X, Sun L, Liang J, Cheng Z, Shi L, Shang Y, Yu W. SIRT7 is a histone desuccinylase that functionally links to chromatin compaction and genome stability. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12235. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frye RA. Characterization of five human cDNAs with homology to the yeast SIR2 gene: Sir2-like proteins (sirtuins) metabolize NAD and may have protein ADP-ribosyltransferase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:273–279. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michishita E, Park JY, Burneskis JM, Barrett JC, Horikawa I. Evolutionarily conserved and nonconserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4623–4635. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.North BJ, Verdin E. Interphase nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling and localization of SIRT2 during mitosis. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen SF, Seiler J, Santiago-Reichelt M, Felbe K, Grummt I, Voit R. Repression of RNA polymerase I upon stress is caused by inhibition of RNA-dependent deacetylation of PAF53 by SIRT7. Mol Cell. 2013;52:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanno M, Sakamoto J, Miura T, Shimamoto K, Horio Y. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6823–6832. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hisahara S, Chiba S, Matsumoto H, Tanno M, Yagi H, Shimohama S, Sato M, Horio Y. Histone deacetylase SIRT1 modulates neuronal differentiation by its nuclear translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15599–15604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800612105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guarente L. Calorie restriction and sirtuins revisited. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2072–2085. doi: 10.1101/gad.227439.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horio Y, Hayashi T, Kuno A, Kunimoto R. Cellular and molecular effects of sirtuins in health and disease. Clin Sci. 2011;121:191–203. doi: 10.1042/CS20100587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bosch-Presegue L, Vaquero A. Sirtuins in stress response: guardians of the genome. Oncogene. 2014;33:3764–3775. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flick F, Luscher B. Regulation of sirtuin function by posttranslational modifications. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:29. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han C, Gu Y, Shan H, Mi W, Sun J, Shi M, Zhang X, Lu X, Han F, Gong Q, Yu W. O-GlcNAcylation of SIRT1 enhances its deacetylase activity and promotes cytoprotection under stress. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1491. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01654-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:225–238. doi: 10.1038/nrm3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez-Redondo P, Vaquero A. The diversity of histone versus nonhistone sirtuin substrates. Genes Cancer. 2013;4:148–163. doi: 10.1177/1947601913483767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang J, Ianni A, Smolka C, Vakhrusheva O, Nolte H, Kruger M, Wietelmann A, Simonet NG, Adrian-Segarra JM, Vaquero A, Braun T, Bober E. Sirt7 promotes adipogenesis in the mouse by inhibiting autocatalytic activation of Sirt1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8352–E8361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706945114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malik S, Villanova L, Tanaka S, Aonuma M, Roy N, Berber E, Pollack JR, Michishita-Kioi E, Chua KF. SIRT7 inactivation reverses metastatic phenotypes in epithelial and mesenchymal tumors. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9841. doi: 10.1038/srep09841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HS, Xiao CY, Wang RH, Lahusen T, Xu XL, Vassilopoulos A, Vazquez-Ortiz G, Jeong WI, Park O, Ki SH, Gao B, Deng CX. Hepatic-specific disruption of SIRT6 in mice results in fatty liver formation due to enhanced glycolysis and triglyceride synthesis. Cell Metab. 2010;12:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carnevale I, Pellegrini L, D’Aquila P, Saladini S, Lococo E, Polletta L, Vernucci E, Foglio E, Coppola S, Sansone L, Passarino G, Bellizzi D, Russo MA, Fini M, Tafani M. SIRT1-SIRT3 axis regulates cellular response to oxidative stress and etoposide. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:1835–1844. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilboa SM, Salemi JL, Nembhard WN, Fixler DE, Correa A. Mortality resulting from congenital heart disease among children and adults in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Circulation. 2010;122:2254–2263. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.947002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fahed AC, Gelb BD, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Genetics of congenital heart disease: the glass half empty. Circ Res. 2013;112:707–720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.300853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng HL, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, Manis JP, Gu Y, Patel P, Bronson R, Appella E, Alt FW, Chua KF. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10794–10799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934713100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan X, Qi H, Li X, Wu F, Fang J, Bober E, Dobreva G, Zhou Y, Braun T. Disruption of spatiotemporal hypoxic signaling causes congenital heart disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2235–2248. doi: 10.1172/JCI88725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buckingham M, Meilhac S, Zaffran S. Building the mammalian heart from two sources of myocardial cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:826–835. doi: 10.1038/nrg1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meilhac SM, Esner M, Kelly RG, Nicolas JF, Buckingham ME. The clonal origin of myocardial cells in different regions of the embryonic mouse heart. Dev Cell. 2004;6:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai CL, Liang X, Shi Y, Chu PH, Pfaff SL, Chen J, Evans S. Isl1 identifies a cardiac progenitor population that proliferates prior to differentiation and contributes a majority of cells to the heart. Dev Cell. 2003;5:877–889. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00363-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dyer LA, Kirby ML. The role of secondary heart field in cardiac development. Dev Biol. 2009;336:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vikram A, Lewarchik CM, Yoon JY, Naqvi A, Kumar S, Morgan GM, Jacobs JS, Li Q, Kim YR, Kassan M, Liu J, Gabani M, Kumar A, Mehdi H, Zhu X, Guan X, Kutschke W, Zhang X, Boudreau RL, Dai S, Matasic DS, Jung SB, Margulies KB, Kumar V, Bachschmid MM, London B, Irani K. Sirtuin 1 regulates cardiac electrical activity by deacetylating the cardiac sodium channel. Nat Med. 2017;23:361–367. doi: 10.1038/nm.4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruan Y, Liu N, Priori SG. Sodium channel mutations and arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:337–348. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shan JP, Pang SC, Wanyan HX, Xie W, Qin XY, Yan B. Genetic analysis of the SIRT1 gene promoter in ventricular septal defects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gui J, Potthast A, Rohrbach A, Borns K, Das AM, von Versen-Hoynck F. Gestational diabetes induces alterations of sirtuins in fetal endothelial cells. Pediatr Res. 2016;79:788–798. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L, Han LS, Ma RJ, Hou XJ, Yu Y, Sun SC, Xu YX, Schedl T, Moley KH, Wang Q. Sirt3 prevents maternal obesity-associated oxidative stress and meiotic defects in mouse oocytes. Cell Cycle. 2015;14:2959–2968. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1026517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen LT, Chen H, Pollock CA, Saad S. Sirtuins-mediators of maternal obesity-induced complications in offspring? FASEB J. 2016;30:1383–1390. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-280743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suter MA, Chen AS, Burdine MS, Choudhury M, Harris RA, Lane RH, Friedman JE, Grove KL, Tackett AJ, Aagaard KM. A maternal high-fat diet modulates fetal SIRT1 histone and protein deacetylase activity in nonhuman primates. FASEB J. 2012;26:5106–5114. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-212878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi H, Enriquez A, Rapadas M, Martin E, Wang R, Moreau J, Lim CK, Szot JO, Ip E, Hughes JN, Sugimoto K, Humphreys DT, McInerney-Leo AM, Leo PJ, Maghzal GJ, Halliday J, Smith J, Colley A, Mark PR, Collins F, Sillence DO, Winlaw DS, Ho JWK, Guillemin GJ, Brown MA, Kikuchi K, Thomas PQ, Stocker R, Giannoulatou E, Chapman G, Duncan EL, Sparrow DB, Dunwoodie SL. NAD deficiency, congenital malformations, and niacin supplementation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:544–552. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1616361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Azevedo PS, Polegato BF, Minicucci MF, Paiva SAR, Zornoff LAM. Cardiac remodeling: concepts, clinical impact, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacologic treatment. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2016;106:62–69. doi: 10.5935/abc.20160005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jayaprasad N. Heart failure in children. Heart Views. 2016;17:92–99. doi: 10.4103/1995-705X.192556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling–concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling: behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–582. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2181–H2190. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fan D, Takawale A, Lee J, Kassiri Z. Cardiac fibroblasts, fibrosis and extracellular matrix remodeling in heart disease. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma S, Feng J, Zhang R, Chen J, Han D, Li X, Yang B, Li X, Fan M, Li C, Tian Z, Wang Y, Cao F. SIRT1 activation by resveratrol alleviates cardiac dysfunction via mitochondrial regulation in diabetic cardiomyopathy mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:4602715. doi: 10.1155/2017/4602715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsu CP, Zhai P, Yamamoto T, Maejima Y, Matsushima S, Hariharan N, Shao D, Takagi H, Oka S, Sadoshima J. Silent information regulator 1 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2010;122:2170–2182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.958033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pillai JB, Isbatan A, Imai S, Gupta MP. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-dependent cardiac myocyte cell death during heart failure is mediated by NAD(+) depletion and reduced Sir2 alpha deacetylase activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43121–43130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prola A, Da Silva JP, Guilbert A, Lecru L, Piquereau J, Ribeiro M, Mateo P, Gressette M, Fortin D, Boursier C, Gallerne C, Caillard A, Samuel JL, Francois H, Sinclair DA, Eid P, Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Lemaire C. SIRT1 protects the heart from ER stress-induced cell death through eIF2 alpha deacetylation. Cell Death Differ. 2017;24:343–356. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Becatti M, Taddei N, Cecchi C, Nassi N, Nassi PA, Fiorillo C. SIRT1 modulates MAPK pathways in ischemic-reperfused cardiomyocytes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:2245–2260. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0925-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang CY, Kuo WW, Yeh YL, Ho TJ, Lin JY, Lin DY, Chu CH, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH, Huang CY. ANG II promotes IGF-IIR expression and cardiomyocyte apoptosis by inhibiting HSF1 via JNK activation and SIRT1 degradation. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21:1262–1274. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alcendor RR, Kirshenbaum LA, Imai S, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Silent information regulator 2 alpha, a longevity factor and class III histone deacetylase, is an essential endogenous apoptosis inhibitor in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2004;95:971–980. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147557.75257.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sundaresan NR, Pillai VB, Wolfgeher D, Samant S, Vasudevan P, Parekh V, Raghuraman H, Cunningham JM, Gupta M, Gupta MP. The deacetylase SIRT1 promotes membrane localization and activation of Akt and PDK1 during tumorigenesis and cardiac hypertrophy. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra46. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oka S, Alcendor R, Zhai PY, Park JY, Shao D, Cho J, Yamamoto T, Tian B, Sadoshima J. PPAR alpha-Sirt1 complex mediates cardiac hypertrophy and failure through suppression of the ERR transcriptional pathway. Cell Metab. 2011;14:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alcendor RR, Gao SM, Zhai PY, Zablocki D, Holle E, Yu XZ, Tian B, Wagner T, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:1512–1521. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000267723.65696.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang X, Chen XF, Wang NY, Wang XM, Liang ST, Zheng W, Lu YB, Zhao X, Hao DL, Zhang ZQ, Zou MH, Liu DP, Chen HZ. SIRT2 acts as a cardioprotective deacetylase in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2017 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemos V, de Oliveira RM, Naia L, Szego E, Ramos E, Pinho S, Magro F, Cavadas C, Rego AC, Costa V, Outeiro TF, Gomes P. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT2 attenuates oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction and improves insulin sensitivity in hepatocytes. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:4105–4117. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hebert AS, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, Yu W, Bailey DJ, Selen ES, Boersma MD, Carson JJ, Tonelli M, Balloon AJ, Higbee AJ, Westphall MS, Pagliarini DJ, Prolla TA, Assadi-Porter F, Roy S, Denu JM, Coon JJ. Calorie restriction and SIRT3 trigger global reprogramming of the mitochondrial protein acetylome. Mol Cell. 2013;49:186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schlicker C, Gertz M, Papatheodorou P, Kachholz B, Becker CFW, Steegborn C. Substrates and regulation mechanisms for the human mitochondrial Sirtuins Sirt3 and Sirt5. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:790–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahn BH, Kim HS, Song SW, Lee IH, Liu J, Vassilopoulos A, Deng CX, Finkel T. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:14447–14452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803790105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Goetzman E, Jing E, Schwer B, Lombard DB, Grueter CA, Harris C, Biddinger S, Ilkayeva OR, Stevens RD, Li Y, Saha AK, Ruderman NB, Bain JR, Newgard CB, Farese RV, Alt F, Kahn CR, Verdin E. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature. 2010;464:121–137. doi: 10.1038/nature08778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hafner AV, Dai J, Gomes AP, Xiao CY, Palmeira CMK, Rosenzweig A, Sinclair DA. Regulation of the mPTP by SIRT3-mediated deacetylation of CypD at lysine 166 suppresses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Aging. 2010;2:914–923. doi: 10.18632/aging.100252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wei T, Huang G, Gao J, Huang C, Sun M, Wu J, Bu J, Shen W. Sirtuin 3 deficiency accelerates hypertensive cardiac remodeling by impairing angiogenesis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006114. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li JY, Chen TS, Xiao M, Li N, Wang SJ, Su HY, Guo XB, Liu H, Yan FY, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Bu PL. Mouse Sirt3 promotes autophagy in AngII-induced myocardial hypertrophy through the deacetylation of FoxO1. Oncotarget. 2016;7:86648–86659. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sundaresan NR, Gupta M, Kim G, Rajamohan SB, Isbatan A, Gupta MP. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2758–2771. doi: 10.1172/JCI39162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sundaresan NR, Bindu S, Pillai VB, Samant S, Pan Y, Huang JY, Gupta M, Nagalingam RS, Wolfgeher D, Verdin E, Gupta MP. SIRT3 blocks aging-associated tissue fibrosis in mice by deacetylating and activating glycogen synthase kinase 3beta. Mol Cell Biol. 2015;36:678–692. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00586-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu L, Gong B, Duan W, Fan C, Zhang J, Li Z, Xue X, Xu Y, Meng D, Li B, Zhang M, Bin Z, Jin Z, Yu S, Yang Y, Wang H. Melatonin ameliorates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in type 1 diabetic rats by preserving mitochondrial function: role of AMPK-PGC-1alpha-SIRT3 signaling. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41337. doi: 10.1038/srep41337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Porter GA, Urciuoli WR, Brookes PS, Nadtochiy SM. SIRT3 deficiency exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury: implication for aged hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H1602–H1609. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00027.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sundaresan NR, Samant SA, Pillai VB, Rajamohan SB, Gupta MP. SIRT3 is a stress-responsive deacetylase in cardiomyocytes that protects cells from stress-mediated cell death by deacetylation of Ku70. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6384–6401. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00426-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo XB, Yan FY, Shan XL, Li JY, Yang Y, Zhang J, Yan XF, Bu PL. SIRT3 inhibits Ang II-induced transdifferentiation of cardiac fibroblasts through beta-catenin/PPAR-gamma signaling. Life Sci. 2017;186:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luo YX, Tang X, An XZ, Xie XM, Chen XF, Zhao X, Hao DL, Chen HZ, Liu DP. SIRT4 accelerates Ang II-induced pathological cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting manganese superoxide dismutase activity. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1389–1398. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sadhukhan S, Liu XJ, Ryu D, Nelson OD, Stupinski JA, Li Z, Chen W, Zhang S, Weiss RS, Locasale JW, Auwerx J, Lin HN. Metabolomics-assisted proteomics identifies succinylation and SIRT5 as important regulators of cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4320–4325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519858113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boylston JA, Sun JH, Chen Y, Gucek M, Sack MN, Murphy E. Characterization of the cardiac succinylome and its role in ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;88:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hershberger KA, Abraham DM, Martin AS, Mao L, Liu J, Gu H, Locasale JW, Hirschey MD. Sirtuin 5 is required for mouse survival in response to cardiac pressure overload. J Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.809897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sundaresan NR, Vasudevan P, Zhong L, Kim G, Samant S, Parekh V, Pillai VB, Ravindra PV, Gupta M, Jeevanandam V, Cunningham JM, Deng CX, Lombard DB, Mostoslavsky R, Gupta MP. The sirtuin SIRT6 blocks IGF-Akt signaling and development of cardiac hypertrophy by targeting c-Jun. Nat Med. 2012;18:1643–1650. doi: 10.1038/nm.2961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kawahara TL, Michishita E, Adler AS, Damian M, Berber E, Lin M, McCord RA, Ongaigui KC, Boxer LD, Chang HY, Chua KF. SIRT6 links histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylation to NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression and organismal life span. Cell. 2009;136:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yu SS, Cai Y, Ye JT, Pi RB, Chen SR, Liu PQ, Shen XY, Ji Y. Sirtuin 6 protects cardiomyocytes from hypertrophy in vitro via inhibition of NF-kappaB-dependent transcriptional activity. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168:117–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01903.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shen P, Feng X, Zhang X, Huang X, Liu S, Lu X, Li J, You J, Lu J, Li Z, Ye J, Liu P. SIRT6 suppresses phenylephrine-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy though inhibiting p300. J Pharmacol Sci. 2016;132:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang XY, Li W, Shen PY, Feng XJ, Yue ZB, Lu J, You J, Li JY, Gao H, Fang S, Li ZM, Liu PQ. STAT3 suppression is involved in the protective effect of SIRT6 against cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2016;68:204–214. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maksin-Matveev A, Kanfi Y, Hochhauser E, Isak A, Cohen HY, Shainberg A. Sirtuin 6 protects the heart from hypoxic damage. Exp Cell Res. 2015;330:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang XX, Wang XL, Tong MM, Gan L, Chen H, Wu SS, Chen JX, Li RL, Wu Y, Zhang HY, Zhu Y, Li YX, He JH, Wang M, Jiang W. SIRT6 protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia/reperfusion injury by augmenting FoxO3alpha-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms. Basic Res Cardiol. 2016;111:13. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0531-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tan KM, Liu ZP, Wang JJ, Xu SW, You TH, Liu PQ. Sirtuin-6 inhibits cardiac fibroblasts differentiation into myofibroblasts via inactivation of nuclear factor kappa B signaling. Transl Res. 2015;165:374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang ZZ, Cheng YW, Jin HY, Chang Q, Shang QH, Xu YL, Chen LX, Xu R, Song B, Zhong JC. The sirtuin 6 prevents angiotensin II-mediated myocardial fibrosis and injury by targeting AMPK-ACE2 signaling. Oncotarget. 2017;8:72302–72314. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li YM, Meng XD, Wang WG, Liu F, Hao ZR, Yang Y, Zhao JB, Yin WS, Xu LJ, Zhao RP, Hu J. Cardioprotective effects of SIRT6 in a mouse model of transverse aortic constriction-induced heart failure. Front Physiol. 2017;8:394. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ryu D, Jo YS, Lo Sasso G, Stein S, Zhang H, Perino A, Lee JU, Zeviani M, Romand R, Hottiger MO, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J. A SIRT7-dependent acetylation switch of GABPbeta1 controls mitochondrial function. Cell Metab. 2014;20:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vakhrusheva O, Smolka C, Gajawada P, Kostin S, Boettger T, Kubin T, Braun T, Bober E. Sirt7 increases stress resistance of cardiomyocytes and prevents apoptosis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ Res. 2008;102:703–710. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Araki S, Izumiya Y, Rokutanda T, Ianni A, Hanatani S, Kimura Y, Onoue Y, Senokuchi T, Yoshizawa T, Yasuda O, Koitabashi N, Kurabayashi M, Braun T, Bober E, Yamagata K, Ogawa H. Sirt7 contributes to myocardial tissue repair by maintaining transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway. Circulation. 2015;132:1081–1093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.D’Onofrio N, Vitiello M, Casale R, Servillo L, Giovane A, Balestrieri ML. Sirtuins in vascular diseases: emerging roles and therapeutic potential. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:1311–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang WT, Gao F, Zhang P, Pang SC, Cui YH, Liu LX, Wei GH, Yan B. Functional genetic variants within the SIRT2 gene promoter in acute myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0176245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cheng J, Cho M, Cen JM, Cai MY, Xu S, Ma ZW, Liu XG, Yang XL, Chen C, Suh Y, Xiong XD. A TagSNP in SIRT1 gene confers susceptibility to myocardial infarction in a Chinese Han population. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0115339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yin X, Pang S, Huang J, Cui Y, Yan B. Genetic and functional sequence variants of the SIRT3 gene promoter in myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0153815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang L, Ma L, Pang S, Huang J, Yan B. Sequence variants of SIRT6 gene promoter in myocardial infarction. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2016;20:185–190. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2015.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Patel MD, Mohan J, Schneider C, Bajpai G, Purevjav E, Canter CE, Towbin J, Bredemeyer A, Lavine KJ. Pediatric and adult dilated cardiomyopathy represent distinct pathological entities. JCI Insight. 2017 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.94382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hussain T, Dragulescu A, Benson L, Yoo SJ, Meng H, Windram J, Wong D, Greiser A, Friedberg M, Mertens L, Seed M, Redington A, Grosse-Wortmann L. Quantification and significance of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Cardiol. 2015;36:970–978. doi: 10.1007/s00246-015-1107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cirino AL, Ho C. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Mefford HC, Stephens K, Amemiya A, Ledbetter N, editors. GeneReviews(R) Seattle: University of Washington; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meyers DE, Basha HI, Koenig MK. Mitochondrial cardiomyopathy pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Tex Heart Inst J. 2013;40:385–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.El-Hattab AW, Scaglia F. Mitochondrial cardiomyopathies. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2016;3:25. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2016.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Durr A, Cossee M, Agid Y, Campuzano V, Mignard C, Penet C, Mandel JL, Brice A, Koenig M. Clinical and genetic abnormalities in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1169–1175. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610173351601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wagner GR, Pride PM, Babbey CM, Payne RM. Friedreich’s ataxia reveals a mechanism for coordinate regulation of oxidative metabolism via feedback inhibition of the SIRT3 deacetylase. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:2688–2697. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martin AS, Abraham DM, Hershberger KA, Bhatt DP, Mao L, Cui H, Liu J, Liu X, Muehlbauer MJ, Grimsrud PA, Locasale JW, Payne RM, Hirschey MD. Nicotinamide mononucleotide requires SIRT3 to improve cardiac function and bioenergetics in a Friedreich’s ataxia cardiomyopathy model. JCI Insight. 2017;2:14. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Potthast AB, Heuer T, Warneke SJ, Das AM. Alterations of sirtuins in mitochondrial cytochrome c-oxidase deficiency. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0186517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kuno A, Hori YS, Hosoda R, Tanno M, Miura T, Shimamoto K, Horio Y. Resveratrol improves cardiomyopathy in dystrophin-deficient mice through SIRT1 protein-mediated modulation of p300 protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:5963–5972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.392050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Paulin R, Dromparis P, Sutendra G, Gurtu V, Zervopoulos S, Bowers L, Haromy A, Webster L, Provencher S, Bonnet S, Michelakis ED. Sirtuin 3 deficiency is associated with inhibited mitochondrial function and pulmonary arterial hypertension in rodents and humans. Cell Metab. 2014;20:827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]