Abstract

Background: The emerging public discourse about the “broken” postdoc system is mostly conceptual. The current work offers an attempt to quantify postdocs’ perceptions, goals, and well-being.

Methods: A survey of 190 postdocs in North America.

Results: This article first reveals a surprisingly unhappy postdoc community with low satisfaction with life scores. Second, it demonstrates how over the course of the fellowship many postdocs lose interest in the goal of pursuing a tenure track academic position (~20%) or in recommending the postdoc track to others (~30%). Finally, we find that among a large number of factors that can enhance satisfaction with life for postdocs (e.g., publication productivity, resources available to them) only one factor stood out as significant: the degree to which atmosphere in the lab is pleasant and collegial.

Conclusions: Our findings can stimulate policy, managerial, and career development improvements in the context of the postdoc system.

Keywords: Postdoc, post-doctorate, well-being, academic career

Introduction

Post-doctorate fellows (i.e. postdocs) are a major force in advancing scientific research, and often are the driving force behind successful labs, especially in the bio-medical area. Not only the sheer number of postdocs is on the rise – the number of postdocs has tripled since 1979 ( Gould, 2015) – but also their research projects require heavier funding ( Davis, 2009; Xuhong, 2013). A common assumption is that PhDs pursue a postdoc position in an academic research institution to enhance their research skills and reputation, which in turn increase their chances of obtaining the ultimate goal: a tenure track academic appointment. While this is a worthy goal to pursue, and there is no doubt that a postdoc position is often key for a future academic appointment, there are growing concerns that the postdoc system is broken and unsustainable ( Alberts et al., 2014; Gould, 2015). Such concerns are mostly heard from postdocs ( Powell, 2015; Smaglik, 2016). Conversely, the academic establishment benefits from maintaining the status quo because the supply of skilled employees like postdocs – that are relatively non-costly and require minimal training and supervision – is highly warranted ( Smaglik, 2016). However, the benefits from a postdoc career for the postdocs themselves are becoming much less evident. Under unstable economic conditions tenure track academic appointments become tremendously difficult to obtain. Recent evidence from the UK, for example, suggests that of 100 science PhD graduates, about 30 will go on to postdoc research, but just 4 will secure permanent academic posts with a significant research component ( Nature editorial, 2014). In the US, the situation is slightly better: 65% of all PhD holders follow the postdoc path but only 15–20% of those gain a tenure track position ( Gould, 2015). Moreover, postdocs that are not able to achieve an academic appointment often become over-qualified for industry positions while losing alternative higher compensation (salaries in the industry) and often putting their personal life (marriage, kids) on hold.

It takes between 12–18 years of academic training to get into the entry level of an academic tenure track position ( Gould, 2015). This very long training process has economic, social, and individual well-being costs. These heavy costs are often complemented with the significant uncertainty surrounding the likelihood of obtaining a tenure track academic appointment. Overall therefore, it might be very useful for potential postdocs to develop a more critical view of the traditional academic postdoc track and of their career choices after completing their PhD.

While discussions of the postdoc reality have been attracting growing attention (e.g., Alberts et al., 2014; Gould, 2013; Powell, 2015; Smaglik, 2016), they have mostly focused on the policy level and lacked empirical assessments at the individual postdoc level. Our aim is to empirically study the perspective of postdocs, to better understand their goals and perceptions, and to be able to promote evidence-based career choices by PhDs considering the postdoc path. We follow recent efforts such as the postdocs survey conducted by Gibbs et al. (2015). Specifically, we pose, at the individual level, the following unanswered research questions:

Given the complex reality postdocs face today

-

(1)

How satisfied are current postdocs?

-

(2)

How likely are they to change – over the course of their fellowship – their key career goal of (typically) obtaining a tenure track appointment?

Methods

To answer our research questions, we conducted a survey of postdocs in North America, mostly in the bio-medical and physical sciences. We emailed the survey to 29 leading postdoc associations in North America (e.g., National Postdocs Association, Rockefeller Postdocs Association, Johns Hopkins Postdoctoral Association) asking them to distribute it among their members. Overall we generated responses from 190 postdocs 1. Respondents’ anonymity was kept. The majority of respondents were positioned in the U.S, with 6 participants from Europe, Asia and Africa 2. Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of the surveyed postdocs. The survey, data, and list of postdoc associations targeted can be found as a supplementary files ( Dataset 1, Supplementary file 1, Supplementary file 2).

A data set including the response of 190 North American postdocs.

Copyright: © 2017 Grinstein A and Treister R

Data associated with the article are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Table 1. Key characteristics of the surveyed postdocs.

Different n are due to missing values. Percentages are of valid cases.

| # of

Postdocs fellowships |

Duration

of postdoc (years) |

# of

publications |

Discipline | Age | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One 70.0% | ≤1 21.3% | 0 2.2% | Biology 43.6% | <30 9.5% | Female 55.1% | |

| Two 26.3% | 2–4 50.0% | 1–3 12.4% | Neuroscience 21.8% | 30–39 78.3% | Male 44.9% | |

| Three 3.2% | 5–8 24.1% | 4–10 50.6% | Medicine 10.9% | 40–49 11.5% | ||

| Four 0.5% | >8 4.7% | >10 34.8% | Engineering 4.2% | >50 0.7% | ||

| Chemistry 3.0% | ||||||

| Environmental science 1.2% | ||||||

| Physics 0.6% | ||||||

| Mathematics 0.6% | ||||||

| Statistics 0.6% | ||||||

| Other 13.5% | ||||||

| n | 190 | 178 | 178 | 165 | 148 | 147 |

| Min-Max | 1–4 | 0.5–18 | 0–65 | - | 27–52 | - |

| Mean | 1.34 | 3.38 | 9.26 | - | 34.89 | - |

In the survey we were especially interested in collecting data regarding satisfaction levels of postdocs as well as their career goals dynamics while accounting for variety of factors that may impact these outcomes such as number of publications and atmosphere in the lab.

Results

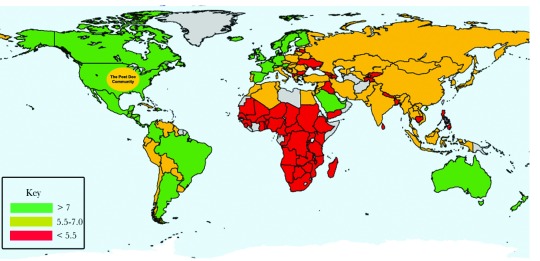

A first set of findings suggests that postdocs are far from being satisfied with their current situation in life with a mean of 4.47 (SD=1.46). Satisfaction was quantified by five items, each reported on a 1–7 scale, based on the established Diener et al.’s (1985) scale; α=.90: “In most ways my life is close to my ideal,” “The conditions of my life are excellent,” “I am satisfied with my life,” “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life,” “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”. Further, 30% of participants demonstrate lower than the median (=4) satisfaction levels. Considering that the established research using the same satisfaction scale typically suggests a positive bias of people when asked about satisfaction with life ( Abdallah et al., 2009; Diener et al., 1985), our results demonstrate a surprisingly low well-being among people that are one step away from their “dream” appointment position and are typically already affiliated with a top-tier academic affiliation. Further, prior work on satisfaction with life of other type of skilled trainees that are roughly at the same age group (e.g., medical students) report much higher satisfaction levels (not lower than 5.2 (e.g., Kjeldstadli et al., 2006; Samaranayake & Fernando, 2011). Although a less “clean” comparison, it is surprising to find that the postdocs in our sample are less content than people in many poor, underdeveloped countries according to a comparable analysis of people’s satisfaction with life across countries ( Figure 1; adapted from Abdallah et al., 2009) 3. Further, the postdocs fall significantly behind the general US population, where many postdocs reside.

Figure 1. A map demonstrating satisfaction with life levels across the world, including the relatively low satisfaction with life of postdocs in North America.

Adapted from Abdallah et al. (2009).

Interestingly, out of a list of potential explanatory variables of satisfaction with life among postdocs – including postdocs’ demographic characteristics (age, gender), personal characteristics (number of postdocs, number of publications, years in postdoc, discipline), publication productivity (number of publications, number of publications as a first author, number of publications based on their postdoc as first authors or in general), PI characteristics (number of publications, frequent interaction of the postdocs with the PI), and lab characteristics (value of equipment, number of postdocs) – only one factor showed significant relationship with satisfaction with life: atmosphere in the lab (r=.247, p=.002). This measure included five items on a 1–7 scale, inspired by Moos’ (2008) Work Environment Scale’s Peer Cohesion sub-dimension aiming to understand how friendly and supportive employees are to each other (α=.80 “The atmosphere in the lab is/was very pleasant,” “I am/was happy to go to work in the morning,” “I view/viewed my lab colleagues as friends,” “I often have/had social interactions with my lab colleagues outside the lab,” “I often collaborate/collaborated on joint projects with my lab colleagues”).

A key consequence of such lack of satisfaction is represented in participants’ responses to a question wondering whether the postdocs will likely to recommend the postdoc track to other who considering it. Only 28.4% “agreed” or “definitely agreed” to recommend the postdoc path to others. Less than a third.

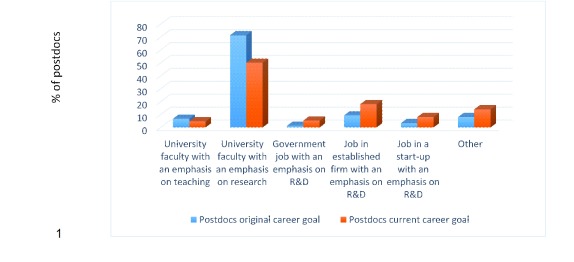

Another finding is that many postdocs are re-considering or re-considered their career goals during their fellowship. We asked participants to share with us their main career goal when starting their postdoc and also at the point of the survey. Options included (a) university faculty with an emphasis on teaching, (b) university faculty with an emphasis on research, (c) government job with an emphasis on R&D, (d) job in an established firm with an emphasis on R&D, (e) job in a start-up with an emphasis on R&D or (f) other. The results (summarized in Figure 2) shows a shift from a goal focusing on academic tenure track position to other goals – mostly industry positions. In our sample, 71.3% of the postdocs began their fellowship with the goal of pursuing a tenure track academic position. When the survey was conducted only 50% maintained a similar career goal. The key career change involves a focus on the industry (established R&D company or a start up) – from 9% and 3%, to 18% and 8%, respectively.

Figure 2. Postdocs career goal change over the span of their fellowship.

Most striking is the finding that 71.3% of the surveyed postdocs began their fellowship with the goal of pursuing a tenure track academic position but when the survey was conducted only 50% maintained this career goal.

Discussion

Many postdocs are facing a well-being paradox. On the one hand, a postdoc position is a huge step towards achieving many postdocs’ central goal of obtaining a tenure track appointment. On the other hand, however, the growing realization that these positions are scarce than ever before, as well as the long, frustrating, and not always rewarding postdoc journey significantly damages the well-being and satisfaction of many postdocs.

Our empirical analysis is a valuable first step in documenting and reflecting on the notion of the well-being paradox of postdocs. Unhappy postdocs is not a good recipe for sustainable success of the postdoc system and for advancing top-tier scientific work. This means – from the perspective of policy makers, university administration, and lab leaders – that there is value in better understanding and catering to the well-being and needs of individual postdocs. Our finding that a key aspect of postdocs’ satisfaction with life involves a positive atmosphere in the lab attest to the importance of “soft”, not-science related factors that are essentials to the sustainability of a successful postdoc system. Such insight can help lab leaders in postdoc recruitment efforts and in optimizing the postdoc experience.

Further, from the perspective of postdocs and prospective postdocs (mostly PhDs), they should consider adopting a more critical view of the traditional academic postdoc track. This may lead to seriously considering all available career options including an industry position following the PhD, an industry postdoc, or a combined academic-industry postdoc. A recent finding that even after achieving a tenure-track academic position, many assistant professors are unhappy ( Nature editorial, 2016), could be another catalysts for postdocs to re-think their career goals. Overall, these trends may require the industry to be more proactive in establishing postdoc positions while requiring the academic system to be more open and flexible with respect to non-academic postdocs and collaboration with the industry.

Overall, our work helps to better understand the well-being of postdocs and its drivers. It provides empirical support to the idea that the current postdoc system is broken and that postdocs are paying a price in well-being terms. Any successful change in the postdoc system would need to enhance postdocs’ well-being and it is our hope that our findings stimulate policy, managerial, and career development improvements that can be pursued.

Data availability

The data referenced by this article are under copyright with the following copyright statement: Copyright: © 2017 Grinstein A and Treister R

Data associated with the article are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication). http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/

Dataset 1

Survey Response: A dataset including the response of 190 North American postdocs. 10.5256/f1000research.12538.d176428 ( Grinstein & Treister, 2017)

Ethics and consent

The first author’s university ethics committee (Northeastern University’s Institutional Review Board) has approved the project “The Unhappy Postdoc” (IRB#: 15-05-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Notes

1Unfortunately we did not get access to the associations’ member lists or to information about them so we lack data on the overall number of survey invitations sent.

2These 6 postdocs where part of the associations and have recently moved back to their home country.

3To be compatible with Abdallah et al.’s (2009) map, we transformed our 1–7 satisfaction with life scale to a 1–10 scale, on which the surveyed postdocs demonstrate a 6.1 satisfaction with life score.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful for a postdoc that helped us with crafting the idea and executing the research but decided to remain anonymous due to the potential negative consequences arising from a study highlighting the “broken system” s/he is part of.

Funding Statement

The study was self-funded

[version 1; referees: 4 approved with reservations]

Supplementary Material

Supplementary file 1: A survey that was distributed among 190 North American postdocs.

Supplementary file 2: List of postdoc associations targeted legend: a list of 29 central postdoc associations in North America that helped distribute the survey among their members.

References

- Abdallah S, Thompson S, Michaelson J, et al. : The Happy Planet Index 2.0: Why Good Lives Don’t Have to Cost the Earth. London: nef (the new economics foundation).2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Alberts B, Kirschner MW, Tilghman S, et al. : Rescuing US biomedical research from its systemic flaws. 2014;111(16):5773–5777. 10.1073/pnas.1404402111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G: Improving the Postdoctoral Experience: An Empirical Approach.In “Science and Engineering Careers in the United States: An Analysis of Markets and Employment”. R. B. Freeman and D. L. Goroff, editors, NBER, Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11619.2009;99–127. 10.7208/chicago/9780226261904.003.0004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, et al. : The Satisfaction With Life Scale. 1985;49(1):71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editorial: Harsh reality. 2014;516(7529):7–8. 10.1038/516007b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Editorial: Young researchers thrive in life after academia. 2016;537(7622):585. 10.1038/537585a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs KD, Jr, McGready J, Griffin K: Career Development among American Biomedical Postdocs. 2015;14(4):ar44. 10.1187/cbe.15-03-0075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould J: How to build a better PhD. 2015;528(7580):22–25. 10.1038/528022a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinstein A, Treister R: Dataset 1 in: The unhappy postdoc: a survey based study. 2017. Data Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldstadli K, Tyssen R, Finset A, et al. : Life satisfaction and resilience in medical school--a six-year longitudinal, nationwide and comparative study. 2006;6(1):48. 10.1186/1472-6920-6-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos R: Work Environment Scale Manual. (4th ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.2008. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- Powell K: The future of the postdoc. 2015;520(7546):144–147. 10.1038/520144a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaranayake CB, Fernando AT: Satisfaction with Life and Depression among Medical Students in Auckland, New Zealand. 2011;124(1341):12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaglik P: Activism: Frustrated postdocs rise up. 2016;530(7591):505–506. 10.1038/nj7591-505a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuhong S: The Impacts of Postdoctoral Training on Scientists’ Academic Employment. 2013;84(2):239–265. 10.2139/ssrn.1438146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]