Abstract

Objectives

Prescribing of homeopathy still occurs in a small minority of English general practices. We hypothesised that practices that prescribe any homeopathic preparations might differ in their prescribing of other drugs.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis.

Setting

English primary care.

Participants

English general practices.

Main outcome measures

We identified practices that made any homeopathy prescriptions over six months of data. We measured associations with four prescribing and two practice quality indicators using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Only 8.5% of practices (644) prescribed homeopathy between December 2016 and May 2017. Practices in the worst-scoring quartile for a composite measure of prescribing quality (>51.4 mean percentile) were 2.1 times more likely to prescribe homeopathy than those in the best category (<40.3) (95% confidence interval: 1.6–2.8). Aggregate savings from the subset of these measures where a cost saving could be calculated were also strongly associated (highest vs. lowest quartile multivariable odds ratio: 2.9, confidence interval: 2.1–4.1). Of practices spending the most on medicines identified as ‘low value’ by NHS England, 12.8% prescribed homeopathy, compared to 3.9% for lowest spenders (multivariable odds ratio: 2.6, confidence interval: 1.9–3.6). Of practices in the worst category for aggregated price-per-unit cost savings, 12.7% prescribed homeopathy, compared to 3.5% in the best category (multivariable odds ratio: 2.7, confidence interval: 1.9–3.9). Practice quality outcomes framework scores and patient recommendation rates were not associated with prescribing homeopathy (odds ratio range: 0.9–1.2).

Conclusions

Even infrequent homeopathy prescribing is strongly associated with poor performance on a range of prescribing quality measures, but not with overall patient recommendation or quality outcomes framework score. The association is unlikely to be a direct causal relationship, but may reflect underlying practice features, such as the extent of respect for evidence-based practice, or poorer stewardship of the prescribing budget.

Keywords: Homeopathy, prescribing, OpenPrescribing

Introduction

Homeopathy is a controversial treatment, and NHS England has recently consulted on future prescribing within the NHS,1 with guidance having been issued, which suggests homeopathic prescribing should not be issued for new patients and should be deprescribed in existing patients.2 Cochrane systematic reviews have assessed the evidence for homeopathy in numerous conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome,3 attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder4 and dementia,5 all of which found insufficient evidence to support use of homeopathy. A 2015 Australian government report concluded that ‘there are no health conditions for which there is reliable evidence that homeopathy is effective’.6

Homeopathy also has low biological plausibility. Homeopathic treatments are made by identifying a substance believed to elicit the symptom being treated (such as nausea) and then diluting this by one drop of the initial substance in 100 drops of water, typically for 30 sequential dilutions, resulting in a solution of 1 in 1060. Although no molecules of the active ingredient remain, homeopaths assert that water has a memory for substances previously diluted in it.7 A drop of this water is then shaken in a container with lactose pills. Homeopaths assert that the pills receive and transmit the qualities memorised previously by the water. Between each dilution, homeopaths state that the flask must be struck firmly against a surface of leather overlaid on horsehair, in order to ‘potentise’ the water.8 Tablets prepared in this fashion can then be prescribed to patients by doctors using a standard NHS FP10 prescription form.

Despite the lack of evidence for homeopathy, and its lack of a plausible mechanism, some NHS doctors still prescribe it. However, there is limited evidence on clinician factors associated with choosing to use homeopathy, mostly based on surveys. German medical students taking elective modules in homeopathy scored lower in ‘science orientation’, but higher in ‘care orientation’ and were less motivated by ‘status’ compared to their peers.9 A commonly cited advantage of homeopathy is safety, and in a small survey of healthcare staff from general practice in London, 70% thought homeopathy could reduce costs for some conditions; however, 55% thought it could increase costs for others.10 Globally, personal use of homeopathy in doctors has a strong association with prescribing of homeopathy.11 There is also some evidence on patient factors associated with choosing homeopathy, again based on surveys: patients are most likely to be female, better educated, have healthier lifestyles and report lower tendency to seek medical help when their child is ill.12,13

Using publicly available data, practices may be measured on their prescribing quality through assessment of the cost-effectiveness, efficacy and safety of medicines prescribed, based on national guidelines. Practices may also be judged by their quality outcomes framework score and patient recommendation rates. We hypothesised that practices that prescribe any homeopathy might differ in their prescribing in other measurable ways. We therefore set out to explore whether general practices prescribing homeopathic remedies also behave differently on these other measures of general practitioner behaviour.

Methods

Study design

Retrospective cross-sectional study incorporating English general practices who have prescribed any homeopathic remedies in the last six months versus those not prescribing any in the same period. We use both univariable and multivariable logistic regression to investigate correlation of this binary ‘homeopathy’ outcome with several measures of practice prescribing quality and behaviour.

Setting and data

We used data from our OpenPrescribing.net project, which imports prescribing data from the monthly prescribing data files published by NHS Digital.14 These contain data on cost and volume prescribed for each drug, dose and preparation, for each month, for each English general practice. We extracted the most recent six months of data available (December 2016 to May 2017 inclusive). This allowed us to determine practices where homeopathy is prescribed and generate composite prescribing measures for practices using the various standard measures of prescribing quality already in use on the OpenPrescribing project (summarised below). We also merged the prescribing data with publicly available data on practices from Public Health England.15 This allowed us to adjust for suspected confounders at the practice level. All standard English practices labelled within the data as a ‘general practice’ were included within the analysis; this excluded prescribing in non-standard settings such as prisons. Additionally, in order to further exclude practices that are no longer active, those without a 2015/2016 quality outcomes framework score were excluded. Using inclusive criteria such as this reduced the likelihood of obtaining a biased sample.

Dependent and independent variables

Homeopathy prescribing was the dependent variable in this study as it is possible to form a logical binary variable (of ‘ever’ vs. ‘never’ prescribing), while this is difficult for the other variables (prescribing and other practice quality measures); however, we set out only to identify potential associations, rather than to suggest causality in either direction between homeopathy use and poor prescribing. Homeopathy prescribing practices were defined as those with at least one prescription for homeopathy within the most recent six months (December 2016 to May 2017 inclusive). Prescribing and other practice quality measures were divided a priori into quartiles for analysis, as this provides more easily interpretable results.

We developed four prescribing quality measurements as independent variables, using a variety of existing metrics developed by OpenPrescribing:

Composite measure score: The 36 current standard prescribing measures on OpenPrescribing16 which have been developed to address issues of cost, safety or efficacy by doctors and pharmacists working in collaboration with data analysts. Each month, OpenPrescribing calculates the percentile that each practice is in, for each measure. Measures are oriented such that a higher percentile corresponds to what would be considered ‘worse’ prescribing (with the exception of those where no value judgement is made, i.e. direct-acting oral anticoagulants17 and pregabalin,18 which are excluded from this analysis). For the purpose of this study, we calculated the mean percentile that each practice was in across all measures, over the previous six months. None of the measures include any homeopathy prescription items.

Aggregate potential savings from measures: Using all standard OpenPrescribing measures where a cost saving can be calculated, we calculated the total aggregated cost saving available per practice over the previous six months. These savings were calculated by comparing each practice’s prescribing with the cost of prescribing at the 10th percentile of performance for each measure.

Composite low-value prescribing score: We assessed prescribing behaviour on a series of 18 ‘low-value’ medications identified in a consultation created by NHS England1 to reduce unwarranted variation, provide clear guidance and reduce unnecessary spending. The action plan included homeopathy prescribing, but this measure was excluded for the purposes of this analysis. For each practice, we took the total spending on all identified medications, over the previous six months.

Aggregate price-per-unit potential savings: In addition to the potential savings from specific prescribing behaviour changes above, we also assessed additional potential efficiency savings using the ‘price-per-unit’19 tool on OpenPrescribing that helps identify whether a practice has cost-saving opportunities for any chemical. This tool compares the price paid, for each dose of any given chemical at any given strength, against the price paid for the same treatment by the practice at the 10th centile, in order to calculate possible efficiency gains. For this study, we aggregated all available savings from price-per-unit over a one-year period (October 2015 to September 2016). There are no savings attributable to switching between homeopathy preparations within the calculated price-per-unit savings.

Additional practice quality scores were obtained from other public sources to be used as independent variables:

Quality outcomes framework: a performance management metric used for general practitioners within the NHS, produced by NHS Digital and available from Public Health England.15

Patient recommendation of practices: describe the percentage of patients that would recommend each practice and available from Public Health England.15

Potential confounding variables

We used a number of demographic metrics (from Public Health England15) to adjust for potential systematic differences between practices and practice populations that may have an influence on prescribing behaviour, including homeopathy use. These were: index of multiple deprivation score, patients with a long-term health condition (%), patients aged over 65 years (%) and whether each practice is a ‘dispensing practice’ (yes or no). We also adjusted for prescribing volume (total items prescribed per practice within the previous six months).

Analysis

We generated basic descriptive statistics to describe the cohort, including medians and proportions as appropriate, stratified by the binary homeopathy prescribing variable. We also used a histogram to describe the distribution of homeopathy prescribing volume for those with at least one prescription. We then performed a series of separate logistic regression analyses with the binary homeopathy variable as the outcome, and each of the four prescribing quality measurements and two practice quality measurements (divided a priori into quartiles) as the predictive variables in separate regression models. We first performed univariable logistic regression, then a priori included all of the variables contained in the potential confounders section above in order to adjust for possible confounding in a multivariable regression model. From these logistic regression models, odds ratios were calculated, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Practices with missing data for a particular variable were not included in models containing that variable. The level of missing data was determined and reported for each variable.

We also report a sensitivity analysis with a narrower definition of homeopathy prescribing, using ≥ 6 prescriptions (rather than ≥ 1) over the same six-month period (corresponding to one per month on average).

Software and reproducibility

Data management was performed using Python and Google BigQuery, with analysis carried out using Stata 14.2. Data, as well as code for the data management and analysis, can be found here: https://figshare.com/s/0511a90af300de6904d6

Results

Population and homeopathy prescribing

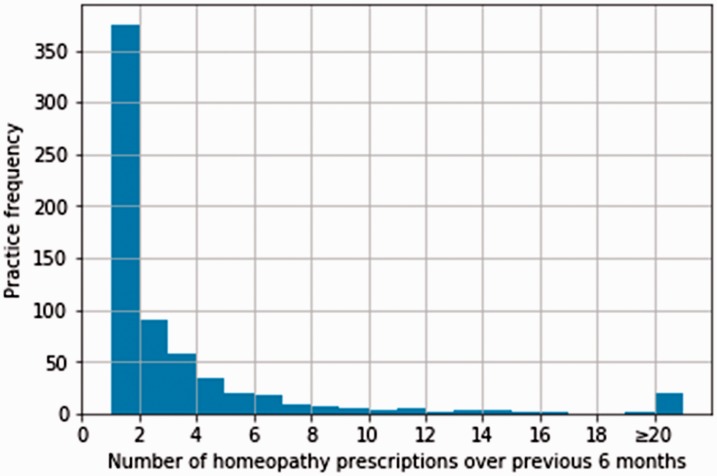

There were 8184 practices within the prescribing dataset labelled as a ‘general practice’. Of these, 566 practices were excluded as they did not have a quality outcomes framework score. A total of 7618 standard current practices were therefore included within the study, and 644 practices (8.5%) met the criteria of having at least one homeopathy prescription within the last six months. Of these, 363 practices had only one homeopathy prescription during this time. There were 2720 homeopathy prescriptions in total over the six-month period, with a total expenditure of £36,532 (mean £13.43 per item). Only 38 practices had > 10 homeopathy prescriptions; only three practices had > 100 prescriptions. The maximum number of homeopathy prescriptions was 252 (see Figure 1). The level of missing data was low, with 98.1% having complete data for all variables (see Appendix 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of number of homeopathy items prescribed in the most recent six months, for the 644 practices that prescribed at least one item. Values ≥20 are aggregated into the final column.

The 6974 practices with no homeopathy prescribing showed lower (better) scores on all standard prescribing measures than practices with homeopathy prescribing (Table 1); however, significance tests were reserved for the later modelling analysis. The median of total items prescribed was higher in practices prescribing homeopathy, while all other practice features were similar between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the practice cohort, stratified by homeopathy prescribing status.

| Prescribing status within last six

months |

||

|---|---|---|

| No homeopathy (IQR) | ≥1 homeopathy prescription (IQR) | |

| Total practices (%) | 6974 (91.5) | 644 (8.5) |

| Median composite measure score (lower is better) | 45.8% (40.0–51.1) | 48.2% (43.0–54.0) |

| Median measure savings compared to first decile practice | £6.1k (3.2k–10.6k) | £9.1k (5.2k–14.1k) |

| Median low value prescribing score (lower is better) | 34.7% (26.0–44.7) | 40.7% (31.4–50.0) |

| Median total price per unit savings | £43k (25k–70k) | £59k (36.8k–88.6k) |

| Median prescribing volume within previous six months | 59.5k (35.6k–94.3k) | 77.3k (52.4–110.3) |

| Median quality outcomes framework score (max possible score 559) | 546 (528–555) | 546 (529–555) |

| Median % of patients recommending practices | 79.3 (70.1–86.9) | 79.8 (70.2–86.4) |

| Median Index of Multiple Deprivation score | 21.9 (14.1–31.8) | 21.3 (13.3–31.3) |

| Median % of patients with long term health conditions | 53.5 (48.3–58.5) | 52.9 (48.3–58.1) |

| Median % of patients over 65 years | 17.2 (12.2–21.4) | 17.1 (12.8–21.7) |

| % of dispensing practices | 13.7 | 13.1 |

IQR: interquartile range.

Association of homeopathy with prescribing quality measures

Each of the four prescribing quality measurements was strongly associated with prescribing any homeopathy. Furthermore, all of the four prescribing quality measurements exhibited a strong, significant trend where practices in each category of worsening prescribing were more likely to prescribe any homeopathy (Table 2). Adjustment for various prespecified practice factors such as demographics and index of multiple deprivation score slightly reduced the size but not significance of associations, with adjustment for prescribing volume accounting for almost all of the change in odds ratio.

Table 2.

Logistic regression with ever prescribing homeopathy as the binary outcome and various prescribing and other general practitioner quality measures as the predictive variables.

| Quartile boundaries | % of practices prescribing homeopathy | Univariable odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | Multivariable odds ratioa | 95% confidence interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite measure score (lower percentile is better) | <40.3 | 5.0% | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 40.3 to 46.0 | 7.8% | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.9 | |

| 46.0 to 51.4 | 8.9% | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2.0 | |

| >51.4 | 12.3% | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.8 | |

| Aggregate savings from measures (£ per month) | <£3.4k | 3.9% | Reference | Reference | ||||

| £3.4k to £6.4k | 7.7% | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.6 | |

| £6.4k to £11.0k | 9.4% | 2.6 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 3.0 | |

| >£11.0k | 13.4% | 3.8 | 2.9 | 5.0 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 4.1 | |

| Total low-value prescribing cost | <£7.6k | 3.9% | Reference | Reference | ||||

| £7.6k to £15.5k | 7.0% | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 2.3 | |

| £15.5k to £27.6k | 10.3% | 2.8 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 1.8 | 3.2 | |

| >£27.6 | 12.8% | 3.6 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 3.6 | |

| Aggregate price-per-unit savings | <£26.0k | 3.5% | Reference | Reference | ||||

| £26.0k to £45.2k | 8.0% | 2.4 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 3.0 | |

| £45.2k to £71.8k | 9.7% | 3.0 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 3.4 | |

| >£71.8k | 12.7% | 4.0 | 3.1 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 3.9 | |

| Quality outcomes framework score | <528 | 8.4% | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 528 to 546 | 8.4% | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | |

| 546 to 555 | 8.5% | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | |

| >555 | 8.6% | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | |

| % of patients recommending practices | <70.1% | 8.4% | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 70.1 to 79.3% | 7.8% | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | |

| 79.3 to 86.9% | 9.8% | 1.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.4 | |

| >86.9% | 8.0% | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | |

QOF: quality outcomes framework; GP: general practitioner.

Adjusted for: index of multiple deprivation, % of patients with a long-term health condition, % of patients aged over 65 years, % of patients recommending practices, dispensing practice (yes or no), total items prescribed within the last six months.

In the composite measures score, those in the worst score category (>51.4) were 2.1 times more likely to prescribe any homeopathy than those in the best category (<40.3) (multivariable odds ratio: 2.1, 95% confidence interval: 1.6–2.8). The aggregate savings from the measures where a cost saving could be calculated also showed a strong, significant trend: those in categories with more available savings were more likely to have prescribed any homeopathy than those in categories with fewer available savings. Prescribing of other ‘low value’ items, as identified by NHS England, was also strongly associated with prescribing any homeopathy: only 3.9% of practices in the best category prescribed any homeopathy, compared to 12.8% in the worst category (multivariable odds ratio: 2.6, confidence interval: 1.9–3.6). Aggregate price-per-unit savings were also strongly associated: in the category where the fewest savings are available where prescribing value has therefore been better optimised, only 3.5% of practices prescribed any homeopathy within the last six months, while for those where the most savings were available, 12.7% of practices prescribed homeopathy (multivariable odds ratio: 2.7, confidence interval: 1.9–3.9).

Association of homeopathy with practice quality measures

Neither of the non-prescribing metrics that assess practice quality (quality outcomes framework score and the percentage of patients recommending practices) were associated with prescribing homeopathy (Table 2). Odds ratios were universally close to 1 (range 0.8–1.2), with no significant associations detected in either the univariable or multivariable logistic regression.

Sensitivity analysis

If only practices that prescribed six prescriptions over the six-month period (i.e. an average of 1 per month) are included as homeopathy prescribers, the results are broadly similar in terms of direction of effect (Supplementary Table 1). Some associations remain significant, although the overall level of significance is lower due only 80 practices (1.1%) being in the homeopathy prescribing group.

Discussion

Summary

We found that prescribing any homeopathy is associated with poorer performance at practice level on a range of standard prescribing measures. We also found a dose–response relationship, with increasing odds of prescribing any homeopathy associated with worsening categories of performance on each prescribing measure: the worse a practice’s performance was on our standard prescribing measures, the more likely they were to have ever prescribed homeopathy. This finding was robust to inclusion of data into the model on a range of plausible confounders. Lower quality outcomes framework scores were not associated with increased odds of prescribing homeopathy nor were patient recommendation scores. We used a highly inclusive criteria for homeopathy prescribing (≥1 prescription over six months), and most practices that did prescribe homeopathy did so in small volumes. Given the low level of homeopathy prescribing, it is therefore remarkable that any difference was found.

Strengths and weaknesses

We included all practices in England with a 2015/2016 quality outcomes framework score, thus minimising the potential for obtaining a biased sample. We excluded 566 practices without a quality outcomes framework score, as many of these practices are no longer active and we reasoned that any practice not participating in quality outcomes framework would be less representative of a ‘typical’ general practice. This may have excluded a small number of practices that opened since the 2015/2016 quality outcomes framework scores were calculated. We also used prospectively gathered prescribing data rather than survey data, eliminating the possibility of recall bias. We were able to measure and adjust for a range of a priori confounding variables related to practice characteristics. Although we do not suggest that the associations found were causal in either direction, this multivariable modelling allowed us to rule out these factors as explaining the observed differences in prescribing. We found that most of the factors we adjusted for made little difference, and only prescribing volume made a notable change to odds ratios.

Due to a large sample size and large effect sizes, we obtained a high level of statistical significance in the associations between homeopathy and measures of prescribing quality. We also observed a dose–response relationship, whereby practices obtaining better prescribing measure scores were much less likely to have prescribed homeopathy, further strengthening the credibility of the associations found. Due to the low volume of homeopathy prescribing, we had limited ability to compare high- and low-volume prescribers of homeopathy. Only 19 practices in England prescribed more than 20 items of homeopathy over six months. Consequently, there is limited statistical power to compare low- and high-volume prescribers, although our sensitivity analysis looking at higher rates of prescribing (Supplementary Table 1) shows broadly similar results to the main analysis.

We were only able to assess associations at practice level, although it would have been interesting to determine if any associations are restricted to clinicians prescribing homeopathy themselves, or whether such associations extend to other clinicians working within the same practice. Although we included data on a range of potential confounders, including large expensively collected datasets that are used consequently in the NHS (such as the quality outcomes framework), it is likely that there were additional unmeasured confounders at play in the relationship between homeopathy and prescribing quality. Indeed, we believe this to be the core finding of the paper: it is unlikely that prescribing homeopathy causes poorer performance, or that poorer performance causes homeopathy use. We propose that both aspects of prescribing are driven by more fundamental issues, such as individual clinicians’ skills on evidence-based medicine; or the extent to which clinicians work together as a team to review prescribing behaviour in their practice’s data, identify areas where they are outliers or exhibit unusual prescribing and take action collectively to address issues identified.

Findings in context

This study is the first to explore the relationship between homeopathy prescribing and other aspects of clinical performance in general practices including prescribing behaviour, overall patient recommendation and measures of clinical quality. Previous work on clinician factors associated with alternative medicine use is generally based on survey data. One Scottish study combined quantitative prescribing data with general practice survey data and found no association of tendency to prescribe homeopathy with length of time practising and reported that doctors without training in homeopathy were less likely to prescribe it.20 Survey data indicate that homeopathy is most often prescribed in NHS settings for minor self-limiting conditions, and often followed the failure of conventional treatment.10,20

Policy implications and interpretation

This analysis is not informative on the question of whether homeopathy should be paid for by the NHS. Indeed, we also find that total NHS expenditure on homeopathy through the NHS prescribing budget is low, at £36,532 over a six-month period. However, our results do demonstrate that prescribing homeopathy is associated with different prescribing styles, specifically with poorer performance on a range of prescribing measures. In our view, this is more important than cost. We believe this strong association between homeopathy use and poorer prescribing in general should raise concerns and may be of interest to those seeking to understand variation in clinical styles and the use of alternative medicine by clinicians. In addition, homeopathy prescribing may provide some limited information about the overall prescribing of a particular practice. However, it is not a reliable predictor of prescribing quality, so we strongly recommend close regular monitoring across a diverse range of prescribing measures as the best way to use data to monitor and improve prescribing.

Summary

Prescribing homeopathy is rare within NHS primary care, but even a low level of prescribing is associated with poorer practice performance on a range of standard prescribing measures. This is unlikely to be a direct causal relationship; it is more likely to reflect deeper underlying features of practices that are harder to measure, such as the extent of respect for evidence-based practice, or the quality of teamwork around optimising treatment while managing the prescribing budget.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix for Is use of homeopathy associated with poor prescribing in English primary care? A cross-sectional study by Alex J Walker, Richard Croker, Seb Bacon, Edzard Ernst, Helen J Curtis and Ben Goldacre in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary Table for Is use of homeopathy associated with poor prescribing in English primary care? A cross-sectional study by Alex J Walker, Richard Croker, Seb Bacon, Edzard Ernst, Helen J Curtis and Ben Goldacre in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare the following: BG has received research funding from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, the Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the NHS National Institute for Health Research School of Primary Care Research, the Health Foundation, and the World Health Organization; he also receives personal income from speaking and writing for lay audiences on the misuse of science. AW, HC, SB and RC are employed on BG’s grants for the OpenPrescribing project. RC is employed by a CCG to optimise prescribing and has received income as a paid member of advisory boards for Martindale Pharma, Menarini Farmaceutica Internazionale SRL and Stirling Anglian Pharmaceuticals Ltd. EE has, many years ago, been trained as a homeopath and today has personal income from speaking and writing for various audiences on critical assessment of homeopathy.

Funding

This work is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, and by a Health Foundation grant (Award Reference Number 7599); and by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School of Primary Care Research (SPCR) grant (Award Reference Number 327). Funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethics approval

This study uses exclusively open, publicly available data, therefore no ethical approval was required.

Guarantor

BG.

Contributorship

AW and BG conceived and designed the study. AW collected and analysed the data with methodological and interpretation input from RC, HC, EE, SB and BG. AW drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. SB was lead engineer on the associated website resource with input from RC, AW, BG and HC. BG supervised the project and is guarantor.

Acknowledgements

Lead engineer on the original OpenPrescribing tool was Anna Powell-Smith.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Azeem Majeed and Julie Morris.

References

- 1.NHS England. NHS England launches action plan to drive out wasteful and ineffective drug prescriptions, saving NHS over £190 million a year. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/2017/07/medicine-consultation/ (2017, last checked 31 July 2017).

- 2.NHS England. Items which should not routinely be prescribed in primary care: guidance for CCGs. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/items-which-should-not-be-routinely-precscribed-in-pc-ccg-guidance.pdf (last checked 18 January 2016).

- 3.Peckham EJ, Nelson EA, Greenhalgh J, Cooper K, Roberts ER, Agrawal A. Homeopathy for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 11: CD009710–CD009710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heirs M, Dean ME. Homeopathy for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder or hyperkinetic disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (4): CD005648–CD005648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarney RW, Warner J, Fisher P, Van Haselen R. Homeopathy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; (1): CD003803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC Statement on Homeopathy and NHMRC Information Paper – Evidence on the effectiveness of homeopathy for treating health conditions. See https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/cam02 (last checked 9 August 2017).

- 7.Fisher P. Is quantum entanglement in homeopathy: a reality? Homeopathy 2016; 105: 209–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldacre B. Bad Science, London, UK: Fourth Estate, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jocham A, Kriston L, Berberat PO, Schneider A, Linde K. How do medical students engaging in elective courses on acupuncture and homeopathy differ from unselected students? A survey. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017; 17: 148–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Haselen RA, Reiber U, Nickel I, Jakob A, Fisher PA. Providing complementary and alternative medicine in primary care: the primary care workers’ perspective. Complement Ther Med 2004; 12: 6–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beer A-M, Burlaka I, Buskin S, Kamenov A, Pettenazzo D, Popova MP, et al. Usage and attitudes towards natural remedies and homeopathy in general pediatrics: a cross-country overview. Glob Pediatr Health 2016; 3: 2333794X15625409–2333794X15625409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wye L, Hay AD, Northstone K, Bishop J, Headley J, Thompson E. Complementary or alternative? The use of homeopathic products and antibiotics amongst pre-school children. BMC Fam Pract 2008; 9: 8–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lert F, Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Rouillon F, Massol J, Guillemot D, Avouac B, et al. Characteristics of patients consulting their regular primary care physician according to their prescribing preferences for homeopathy and complementary medicine. Homeopathy 2014; 103: 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Digital prescribing data. See http://content.digital.nhs.uk/gpprescribingdata (last checked 14 March 2017).

- 15.Public Health England. Public health profiles. See https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/general-practice/data (last checked 31 July 2017).

- 16.OpenPrescribing measures. See https://openprescribing.net/measures (last checked 31 July 2017).

- 17.Openprescribing – Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) prescribing. See https://openprescribing.net/measure/doacs/ (last checked 13 March 2017).

- 18.OpenPrescribing – Prescribing of pregabalin. See https://openprescribing.net/measure/pregabalin/ (last checked 13 March 2017).

- 19.Croker R, Walker AJ, Bacon S, Curtis HJ, French L and Goldacre B. A new mechanism to identify cost savings in NHS prescribing: minimising ‘Price-Per-Unit’, a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e019643. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Ekins-Daukes S, Helms PJ, Taylor MW, Simpson CR, McLay JS. Paediatric homoeopathy in general practice: where, when and why? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 59: 743–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix for Is use of homeopathy associated with poor prescribing in English primary care? A cross-sectional study by Alex J Walker, Richard Croker, Seb Bacon, Edzard Ernst, Helen J Curtis and Ben Goldacre in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Supplemental material, Supplementary Table for Is use of homeopathy associated with poor prescribing in English primary care? A cross-sectional study by Alex J Walker, Richard Croker, Seb Bacon, Edzard Ernst, Helen J Curtis and Ben Goldacre in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine