Abstract

Objectives:

Although a range of factors shapes health and well-being, institutionalized racism (societal allocation of privilege based on race) plays an important role in generating inequities by race. The goal of this analysis was to review the contemporary peer-reviewed public health literature from 2002-2015 to determine whether the concept of institutionalized racism was named (ie, explicitly mentioned) and whether it was a core concept in the article.

Methods:

We used a systematic literature review methodology to find articles from the top 50 highest-impact journals in each of 6 categories (249 journals in total) that most closely represented the public health field, were published during 2002-2015, were US focused, were indexed in PubMed/MEDLINE and/or Ovid/MEDLINE, and mentioned terms relating to institutionalized racism in their titles or abstracts. We analyzed the content of these articles for the use of related terms and concepts.

Results:

We found only 25 articles that named institutionalized racism in the title or abstract among all articles published in the public health literature during 2002-2015 in the 50 highest-impact journals and 6 categories representing the public health field in the United States. Institutionalized racism was a core concept in 16 of the 25 articles.

Conclusions:

Although institutionalized racism is recognized as a fundamental cause of health inequities, it was not often explicitly named in the titles or abstracts of articles published in the public health literature during 2002-2015. Our results highlight the need to explicitly name institutionalized racism in articles in the public health literature and to make it a central concept in inequities research. More public health research on institutionalized racism could help efforts to overcome its substantial, longstanding effects on health and well-being.

Keywords: institutionalized racism, structural racism, social inequities, racial disparities, health policy, public health

Although overall health in the United States has improved dramatically during the past century, longstanding racial/ethnic disparities in health (ie, preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health) persist.1 For decades, the public health community has focused attention on eliminating health disparities.2 However, a recent shift to understand the determinants of health equity has led to a change from the language of health disparities to that of health inequities. Health inequities are systematic, socially produced, and unjust differences in health that could be avoided by reasonable means.3 Goldberg4 described an “inescapable ethical valence” in the term health inequities that is absent from the term disparities. This ethical valence is necessary for understanding the role that institutionalized racism (societal allocation of privilege based on race) plays in contributing to unjust health outcomes. Although a range of factors shapes health and well-being, racism plays a crucial role in generating inequities by race.5 During the past 20 years, research documenting racism and health inequities has grown.6 Additionally, the call to discuss racism and health—rather than race and health—is becoming more pronounced.7–9

Racism occurs at the institutional, interpersonal, and internal levels.10 Much of the public health literature on racism has focused on understanding the impact of interpersonal racism and documenting individual experiences of perceived discrimination or implicit biases based on race.11 Although this contribution is important, our understanding of how racism functions at an institutional level—in our structures, institutions, policies, and practices—is nascent as it relates to individual and population health.9,12

Awareness of the need for the public health field to address institutionalized racism is growing. Institutionalized racism is defined as the macrolevel systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial/ethnic groups.13 Most notably, the American Public Health Association’s immediate past president, Dr Camara Jones, launched a national campaign against racism in 2015 in which she posited that racism is a “system of structuring opportunities and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks (which is what we call ‘race’).”7 Her conceptualization acknowledges the institutional manifestations of racism, not just the interpersonal or internal manifestations. Outside of traditional public health discourse, the concept and effects of institutionalized racism have been magnified by multiple police shootings of unarmed black men. The subsequent formation of activist movements such as Black Lives Matter calls attention to the role that institutions (eg, law enforcement) play in underresourced communities of color.14 These movements amplify the often marginalized voices of those who have experienced the negative health impacts of institutionalized racism.15 Yet, even as institutionalized racism and its effects are increasingly present in the news, television, and social media, whether the public health research community is explicitly mentioning institutionalized racism in published research is unclear.14,16

Fifteen years ago, in her article “Confronting Institutionalized Racism,” Jones17 challenged the public health community to conduct research that confronts racism directly. Although her article was not the first of its kind in public health, or by the author, this work served as a clarion call to public health researchers in the 21st century. She outlined 7 challenges for public health scientists to meaningfully address institutionalized racism—the first being to “name racism.” Naming institutionalized racism refers to explicitly and publicly using language and analysis that describes an issue as a matter of racial justice. For Jones, naming institutionalized racism leads to exploring the question, “How is racism operating here?” and subsequently mobilizing for action.17 Naming institutionalized racism means not simply using race as a descriptor in analyses and manuscripts, but actually naming the underlying processes (ie, racism) that have created differences by race.

Since Jones’s challenge, little has been done to systematically examine whether and how public health scientists have heeded the call to name institutionalized racism in their peer-reviewed publications on racial inequality and disparities. We conducted a systematic review of the contemporary peer-reviewed public health literature to (1) determine whether public health researchers are naming (ie, explicitly mentioning) institutionalized racism in the titles and abstracts of their peer-reviewed publications and (2) explore the depth of discussion on the concept of institutionalized racism when the term was used.

Methods

We used a systematic method to identify and analyze relevant public health literature, including 6 inclusion criteria and a rationale for each criterion (Table 1): the article had to be indexed in Ovid/MEDLINE and/or PubMed/MEDLINE; contain at least 1 of the primary search terms in the title and/or abstract; be published between 2002 and 2015; address the US context; be published in 1 of the 50 highest-impact journals; and be published in any format (ie, original research, commentary, theoretical article). Understanding that the concept of institutionalized racism might be mentioned in various ways, we used the following search terms: “structural racism,” “systemic racism,” “systematic racism,” “institutional racism,” “institutionalized racism,” and “institutionalised racism.” The term had to appear in the title or abstract of the article. PubMed/MEDLINE did not allow the search to identify only references with adjacent 2-word search terms. Articles that included the words of the search terms but not as adjacent 2-word terms were manually excluded for not having the primary search terms as per the criteria of this search.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria and rationale for a systematic review of articles on institutionalized racism,a United States, 2002-2015

| Inclusion Criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| The article was indexed in Ovid/MEDLINE and/or PubMed/MEDLINE. | Although public health literature may encompass many journals published outside of these 2 databases, they are the most frequently used databases in the public health field and most comprehensively address the multidisciplinary field of public health research. |

| The reference contained at least 1 of the primary search terms in the title and/or abstract: institutional racism, institutionalized racism, institutionalised racism, structural racism, systemic racism, or systematic racism. | These terms may be used interchangeably to represent the concept of “institutionalized racism.” Articles must include these terms in the title and/or abstract (and not simply appear anywhere in the article) for 2 reasons: (1) databases do not allow word-searching of the full text, and (2) to capture the most relevant discourse on structural racism, the primary search terms should appear in the title and/or abstract. |

| The article was published between 2002 and 2015. | The critical article “Confronting Institutionalized Racism” by Jones was published in 2002.17 This search sought to document the concept and measurement of institutionalized racism since that article was published. |

| The article addressed the US context (ie, was not international focused). | Racism in its multiple forms is an important concept throughout the world, but its meaning and experience are rooted in the societal context in which they arise. This review focused on the US context and, thus, excluded articles with a primary focus that was international. |

| The article was published in 1 of the 50 highest-impact journals in 6 public health and public health-related categories. | This review was concerned with the discourse in the multidisciplinary field of public health. The 50 highest-impact journals were identified using the impact factors from the 2014 InCites Journal Citation Reports in each of the following categories: (1) health care sciences and services; (2) health policy and services; (3) general and internal medicine; (4) nursing; (5) public, environmental, and occupational health; and (6) social sciences, biomedical. |

| The article was published in any format (original research, commentary, letter to the editor, theoretical article, or literature review). | This review was concerned with discourse on the concept of institutionalized racism. Commentaries and other non-original research articles were included to give the most complete picture possible of the way the concept was being used, discussed, defined, and measured across the literature. |

aInstitutionalized racism is the macrolevel systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial/ethnic groups.13

To most effectively capture the naming of institutionalized racism in the multidisciplinary field of public health, we searched articles from the 50 highest-impact journals in each of 6 categories that most closely represented the public health field and that were indexed in PubMed/MEDLINE and/or Ovid/MEDLINE. We used the most recent (2014) list of categories available from InCites Journal Citation Reports by Thomson Reuters and included the 6 categories that were most representative of the public health literature: (1) health care sciences and services; (2) health policy and services; (3) general and internal medicine ; (4) nursing; (5) public, environmental, and occupational health; and (6) social sciences, biomedical (Table 1). Some journals appeared in more than 1 category, and 1 category had only 38 journals listed. Thus, from the 50 highest-impact journals listed in each of 6 categories, we included articles from a total of 249 journals. (A full list of the 2014 Journal Citation Reports categories and the list of 249 journals included in the 6 categories used for this review are available upon request.)

Abstraction

Once we identified all articles that met all inclusion criteria, we read the full text of each one for use of any of the aforementioned search terms. We recorded which of the 6 search terms were most frequently used in the text of the article. We also recorded the following items for each article: (1) author(s), year of publication, and name of journal; (2) type of article; and (3) use and frequency of the search term used most frequently. We excluded the appearance of search terms in the references section. We used NVivo 10 software for qualitative analysis and coding.18

Analysis

After coding all articles, we completed a qualitative analysis to determine whether each article explored institutionalized racism as a core concept or secondary concept, which we defined by asking the question, “If all the content on institutionalized racism were removed from the article, would the article still communicate its main message?” If the answer was yes, we coded the article as institutionalized racism as a secondary concept; if the answer was no, we coded the article as institutionalized racism as a core concept. One investigator (K.A.M.) completed this analysis, a second investigator (R.R.H.) reviewed and verified it, and a third investigator (K.B.K.) reconciled conclusions when necessary.

In addition, we tabulated data on the number of articles that met search criteria, journal rank in Journal Citation Reports category, total number of journal citations, and journal impact factor. Because this analysis did not involve human subjects research, institutional review board approval was not required.

Results

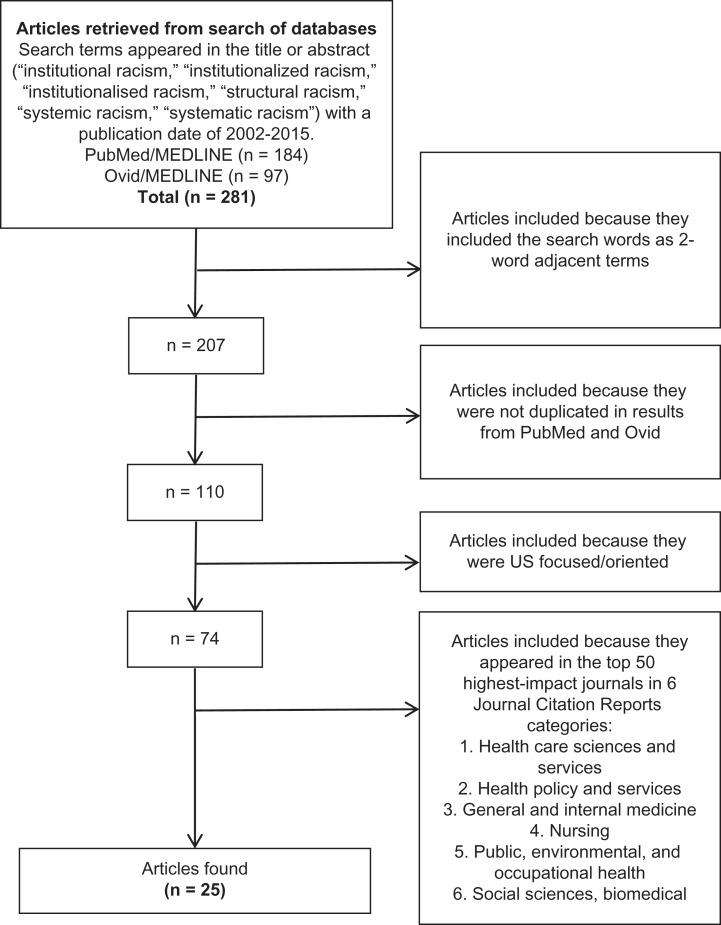

We identified 207 articles that met our first 3 inclusion criteria. Of those articles, 97 were indexed in both Ovid/MEDLINE and PubMed/MEDLINE (ie, duplicates). After applying our inclusion criteria, we found that, of the articles published in the 249 highest-impact journals representing the public health field in the United States during the 14-year period, only 25 articles named institutionalized racism explicitly in the title or abstract (Figure 1). Of the 25 articles, 19 were published between 2011 and 2015.

Figure.

Diagram of methodology and number of articles at each step of the process in a literature review of articles naming (ie, explicitly mentioning) in their title or abstract institutionalized racism, 2002-2015. Institutionalized racism is the macrolevel systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial/ethnic groups.13 PubMed/MEDLINE did not allow the search to identify only references with adjacent 2-word search terms. Articles that included the words of the search terms but not as adjacent 2-word terms were manually excluded for not having the primary search terms as per the criteria of this search.

Naming Institutionalized Racism

All articles mentioning the term “institutionalised racism” were eventually excluded during application of our fourth inclusion criterion, which required that the study focus on the United States. One article used the terms institutional racism and institutionalized racism twice each, but we coded it as primarily using the term institutionalized racism because that term appeared in the article’s abstract and conclusion.19 Although the term institutional racism was used in the most articles (n = 15), the term structural racism appeared the most frequently across all articles (n = 181 total occurrences, most of which were in 2 articles20,21) and was the most commonly preferred term (in 12 articles) (Table 2).15,20,21,25,27,29,30,33,35,39–41

Table 2.

Type of article, institutionalized racism as a core or secondary topic, and number of search terms in the title or abstract of each included article, United States, 2002-2015

| Author, Year | Journal | Title | Article Type | Search Term(s) Appears in Abstract (Not Title) | Core or Secondary Concepta | Search Term, No. of Times Used in Title or Abstract | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Institutional Racism” | “Institutionalized Racism” | “Structural Racism” | “Systemic Racism” | ||||||

| Metzler et al,22 2003 | American Journal of Public Health | Addressing Urban Health in Detroit, New York City, and Seattle Through Community-Based Participatory Research Partnerships | OR | X | C | 7 | — | — | — |

| Armstrong et al,19 2004 | Social Science & Medicine | United States Coronary Mortality Trends and Community Services Associated With Occupational Structure, Among Blacks and Whites, 1984-1998 | OR | X | S | 2 | 1 | — | — |

| Evans,23 2004 | Western Journal of Nursing Research | Cultural and Ethnic Differences in Content Validation Responses | OR | X | S | 5 | — | — | — |

| Ford and Kelly,24 2005 | Health Services Research | Conceptualizing and Categorizing Race and Ethnicity in Health Services Research | LR | X | C | 1 | 7 | — | — |

| Holmes,25 2006 | PLoS Medicine | An Ethnographic Study of the Social Context of Migrant Health in the United States | OR | X | S | 1 | — | 1 | — |

| Paradies,11 2006 | International Journal of Epidemiology | A Systematic Review of Empirical Research on Self-Reported Racism and Health | LR | X | C | — | — | — | 7 |

| Kramer and Hogue,26 2009 | Epidemiologic Reviews | What Causes Racial Disparities in Very Preterm Birth? A Biosocial Perspective | LR | X | C | — | 2 | — | — |

| McAllister et al,27 2009 | American Journal of Public Health | Root Shock Revisited: Perspectives of Early Head Start Mothers on Community and Policy Environments and Their Effects on Child Health, Development, and School Readiness | OR | X | S | — | — | 1 | — |

| Albert et al,28 2010 | Archives of Internal Medicine | Perceptions of Race/Ethnic Discrimination in Relation to Mortality Among Black Women: Results From the Black Women’s Health Study | OR | X | C | 6 | 22 | — | — |

| Ford and Airhihenbuwa,29 2010 | American Journal of Public Health | Critical Race Theory, Race Equity, and Public Health: Toward Antiracism Praxis | CM | X | C | — | 1 | 5 | — |

| Steinecke and Terrell,30 2010 | Academic Medicine | Progress for Whose Future? The Impact of the Flexner Report on Medical Education for Racial and Ethnic Minority Physicians in the United States | TA | X | C | 3 | — | 4 | — |

| Cene et al,31 2011 | Journal of General Internal Medicine | Understanding Social Capital and HIV Risk in Rural African American Communities | OR | X | S | 5 | 2 | — | — |

| Shavers et al,32 2012 | American Journal of Public Health | The State of Research on Racial/Ethnic Discrimination in the Receipt of Health Care | LR | X | C | 11 | — | — | — |

| Viruell-Fuentes et al,33 2012 | Social Science & Medicine | More Than Culture: Structural Racism, Intersectionality Theory, and Immigrant Health | TA | X | C | — | — | 8 | — |

| Chattopadhyay et al,34 2013 | Journal of Bioethical Inquiry | Bioethics and Its Gatekeepers: Does Institutional Racism Exist in Leading Bioethics Journals? | LE | X | C | 6 | — | — | — |

| Hall and Fields,35 2013 | Nursing Outlook | Continuing the Conversation in Nursing on Race and Racism | TA | X | C | 2 | — | 7 | 1 |

| Purtle,36 2013 | American Journal of Public Health | Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States: A Health Equity Perspective | TA | X | C | 1 | 6 | — | — |

| Feagin and Bennefield,37 2014 | Social Science & Medicine | Systemic Racism and U.S. Health Care | TA | C | 5 | 2 | 1 | 23 | |

| Lukachko et al,20 2014 | Social Science & Medicine | Structural Racism and Myocardial Infarction in the United States | OR | C | — | — | 91 | 2 | |

| Paradies et al,38 2014 | Journal of General Internal Medicine | A Systematic Review of the Extent and Measurement of Healthcare Provider Racism | LR | X | S | 3 | — | — | 4 |

| Sabo et al,39 2014 | Social Science & Medicine | Everyday Violence, Structural Racism and Mistreatment at the US-Mexico Border | OR | S | 1 | — | 6 | — | |

| Scott et al,40 2014 | AIDS and Behavior | Peer Social Support Is Associated With Recent HIV Testing Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men | OR | X | S | — | — | 2 | — |

| Jee-Lyn García and Sharif,15 2015 | American Journal of Public Health | Black Lives Matter: A Commentary on Racism and Public Health | CM | X | C | — | — | 8 | — |

| Wallace et al,21 2015 | American Journal of Public Health | Joint Effects of Structural Racism and Income Inequality on Small-for-Gestational-Age Birth | OR | C | — | — | 42 | — | |

| Weiler et al,41 2015 | Health Policy and Planning | Food Sovereignty, Food Security and Health Equity: A Meta-Narrative Mapping Exercise | LR | X | S | — | — | 5 | — |

| Total occurrences of each search term | 59 | 43 | 181 | 37 | |||||

Abbreviations: —, not available; C, core concept; CM, commentary; LE, letter to the editor; LR, literature review; OR, original research; S, secondary concept; TA, theoretical article.

aCore or secondary concept refers to whether institutionalized racism was a core or secondary concept in the article. Institutionalized racism is the macrolevel systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial/ethnic groups.13

Of the 249 highest-impact journals included in this review, only 14 journals published articles that met our search criteria. Of the 6 Journal Citation Reports categories included in this review, the category with the most included articles was “public, environmental, and occupational health” (n = 15 articles) (Table 3). Twenty-three of the 25 articles were published in journals that were ranked among the top 25 in their respective categories. Two journals that had 1 article each were ranked lower than 25th in their respective categories: Western Journal of Nursing Research (ranked 50th in the nursing category) and Journal of Bioethical Inquiry (ranked 31st in the social sciences, biomedical category).

Table 3.

Rankings of journals in which articles mentioning institutionalized racism in the title or abstract were found, number of articles that met search criteria, number of journal citations, and journal impact factor, by category established by 2014 InCites Journal Citation Reports (JCR), 2002-2015

| JCR Category | Journal | No. of Articles That Met Search Criteria | Journal Rank in JCR Category | No. of Journal Citationsa | Journal Impact Factorb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health care sciences and services | Health Policy and Planning | 1 | 7 | 2997 | 3.470 |

| Journal of General Internal Medicine | 2 | 8 | 13 886 | 3.449 | |

| Academic Medicine | 1 | 17 | 9436 | 3.060 | |

| Health policy and services | Health Services Research | 1 | 9 | 5334 | 2.781 |

| General and internal medicine | Archives of Internal Medicine | 1 | 6 | 38 021 | 17.333 |

| PLoS Medicine | 1 | 7 | 18 649 | 14.429 | |

| Journal of General Internal Medicine | 2 | 24 | 13 886 | 3.449 | |

| Nursing | Nursing Outlook | 1 | 12 | 898 | 1.588 |

| Western Journal of Nursing Research | 1 | 50 | 1352 | 1.032 | |

| Public, environmental, and occupational health | International Journal of Epidemiology | 1 | 2 | 16 999 | 9.176 |

| Epidemiologic Reviews | 1 | 4 | 3063 | 6.667 | |

| American Journal of Public Health | 7 | 13 | 29 771 | 4.552 | |

| AIDS and Behavior | 1 | 19 | 6376 | 3.728 | |

| Social Science & Medicine | 5 | 38 | 30 874 | 2.890 | |

| Social sciences, biomedical | AIDS and Behavior | 1 | 2 | 6376 | 3.728 |

| Social Science & Medicine | 5 | 4 | 30 874 | 2.890 | |

| Journal of Bioethical Inquiry | 1 | 31 | 165 | 0.747 | |

| Total | 32c | 15d | 228 957 | 4.998d |

aThe total number of times that a journal has been cited by all journals, provided in the 2014 listing by InCites Journal Citation Reports, which calculates the number of total citations for each journal yearly.

bThe journal impact factor provided in this table is from the 2014 listing by InCites Journal Citation Reports, which calculates an impact factor for each journal yearly.

cThe total number of articles that explicitly named “institutionalized racism” was 25. Total includes duplications, because some journals were represented in more than 1 category. Institutionalized racism is the macrolevel systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial/ethnic groups.13

dThese numbers represent the mean rank and mean impact factor across all journals in the table.

Included articles comprised 5 types of articles: commentaries (n = 2), original research articles (n = 12), theoretical articles (n = 4), letters to the editor (n = 1), and literature reviews (n = 6) (Table 4). We found that the American Journal of Public Health had both the most articles that named institutionalized racism and the widest range of article types, with 2 commentaries, 3 original research articles, 1 theoretical article, and 1 literature review.

Table 4.

Number of articles mentioning institutionalized racisma in title or abstract in a review of the literature, by type of article, 2002-2015

| Journal | Commentary | Original Research | Theoretical Paper | Letter to the Editor | Literature Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Medicine | — | — | 1 | — | — |

| AIDS and Behavior | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| American Journal of Public Health | 2 | 3 | 1 | — | 1 |

| Archives of Internal Medicine | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| Epidemiologic Reviews | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Health Policy and Planning | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Health Services Research | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| International Journal of Epidemiology | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Journal of Bioethical Inquiry | — | — | — | 1 | — |

| Journal of General Internal Medicine | — | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| Nursing Outlook | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| PLoS Medicine | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| Social Science & Medicine | — | 3 | 2 | — | — |

| Western Journal of Nursing Research | — | 1 | — | — | — |

| Total articles by type | 2 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

Abbreviation: —, article not found in journal.

aInstitutionalized racism is the macrolevel systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and processes that interact with one another to generate and reinforce inequities among racial/ethnic groups.13

Centrality of Institutionalized Racism

Institutionalized racism was a core concept in 16 of the 25 articles, and these articles included commentaries (n = 2), original research articles (n = 4), theoretical articles (n = 5), letters to the editor (n = 1), and literature reviews (n = 4).11,15,20–22,24,26,28–30,32–37 The other 9 articles in which institutionalized racism was a secondary concept included 7 original research articles and 2 literature reviews.19,23,25,27,31,38,39–41 In general, these articles mentioned the concept in the introduction and/or the discussion section, but the concept was not central to the research question.

Discussion

Despite the 2002 article by Jones, which called for public health researchers to confront institutionalized racism, the number of articles in the contemporary peer-reviewed public health literature that named institutionalized racism in their titles or abstracts from 2002 through 2015 was small. Although researchers may have studied the effects of institutionalized racism by analyzing residential segregation, mass incarceration, housing discrimination, concentrated poverty, and food insecurity, to name a few, during these years, they did not highlight the phrase “institutionalized racism” in the title or abstract of their study.

In the law and justice literature, naming is well understood as vital to the processes of achieving justice. Indeed, naming often results in a critical transformation of the level and type of legal dispute that may occur. Naming is difficult to study empirically, but naming is worthwhile in that it can result in a focus on the level and kind of dispute in a society with an understanding of the initial injury. Felstiner and colleagues42 used the example of asbestosis, explaining that it became acknowledged as a disease and the basis of a claim for compensation when shipyard workers came to understand and name their condition as a problem. In this vein, if we in the public health field were to name institutionalized racism as a fundamental cause of health inequities, then perhaps we could imagine and work more effectively toward a society in which the initial and ongoing injuries of living by a person of color in America can be better understood.

Dr Jones prioritized naming institutionalized racism because institutional factors perpetuate historical injustices and allow inequities to persist. By naming institutionalized racism explicitly in the peer-reviewed literature, researchers can highlight how injustice and discrimination have been codified, reinforced, and propagated in our health and public health systems. By being explicit about the ways in which some historical and contemporary systems and institutions are designed to alienate or subjugate people of color,13 we can analyze how these external factors influence both individual behaviors and outcomes as well as population health patterns. Institutionalized racism and its deleterious health consequences have been chronicled and debated in many other disciplines, including but not limited to geography, sociology, African American studies, American Indian studies, and the history of science, which can be of use to public health scholars going forward.43

To fully understand how institutionalized racism affects health and well-being in the United States, public health scholars must develop and use innovative methods and measures to capture data on the exposure to and health effects of institutionalized racism, think more broadly about disrupting the implicit biases that perpetuate institutionalized racism, and engage with scholarship from other disciplines. Research shows the physiological and public health consequences of interpersonal racism, but little exists in the public health literature about how institutionalized racism influences outcomes.9

Centering Institutionalized Racism

We found very few explicit uses of the term institutionalized racism, or related terms, in the titles and abstracts of articles in the public health literature. Of the 25 articles we found, only 16 articles included institutionalized racism as a core concept, 4 of which were original research articles. Although our methodology could not measure the full extent of the literature on institutionalized racism as a core concept, this small number of articles suggests a scarcity of original public health research on the topic during 2002-2015.

To heed the call of Dr Jones’s national campaign against racism, public health researchers will need to conduct scholarly work to analyze and evaluate institutionalized racism (as both a primary and a secondary concept) and submit it for publication, and journal editors and peer reviewers should encourage—perhaps even demand—submissions that name institutionalized racism and carefully engage with the concept. If this happens, the number of public health and original research articles that treat institutionalized racism as a determinant of health may grow.

The limited number of original research articles that name institutionalized racism or a similar term in the title or abstract is likely due in part to the complex nature of the concept and a paucity of robust measures of institutionalized racism available in the literature. Because institutionalized racism manifests itself in various structures, policies, and systems, a straightforward way to measure it does not exist. Measuring institutionalized racism in a systematic way is necessary to find solutions to the problem. More public health research on institutionalized racism could help efforts to overcome its substantial, longstanding effects on health and well-being.

Limitations

This review had several limitations. First, we included in our analysis only the highest-impact journals from 6 categories to concentrate on that set of the literature and we excluded international articles and those in lower-impact journals. As a result, relevant articles in lower-impact journals may not have been reviewed for this study. In addition, this review excluded literature that was not published in peer-reviewed journals. As such, we did not include the dialogue on institutionalized racism from community-based, government, nonprofit, or media reports that could inform published public health research. We acknowledge that many scholars have explored how practices and policies, such as redlining and mass incarceration, disproportionately affect populations of color and are influenced by racist ideology, but some of these works might fail to explicitly name institutionalized racism as the overarching mechanism through which these policies are enacted and maintained.

Potentially relevant articles may have been excluded because they did not include search terms in the title or abstract. Also, we may have missed relevant articles that discussed a topic whose underlying cause was related to institutionalized racism (eg, mass incarceration) because the term was not used in the title or abstract. Also, it is possible that other terms were used to represent similar concepts, such as systemic discrimination, structural bias, racism, critical race praxis, and health inequities. These terms might represent the concept of institutionalized racism or closely related concepts but would not have been captured by our study.

Conclusion

This review, although not representative of the entire discourse in public health literature about institutionalized racism, nonetheless highlights how rarely institutionalized racism is named in the titles or abstracts of peer-reviewed, published work. This review adds credence to the call by Dr Jones and others for scholars to identify and name the mechanism through which health injustice is perpetuated and how historical and contemporary policies have negatively targeted and affected underresourced communities of color.8,9,44

Some public health researchers have mentioned institutionalized racism in their work.20,28,33,37,41 Others—primarily through commentary and in discussion sections—have begun to identify the mechanisms by which institutionalized racism affects public health.37 Despite this finding, the literature does not yet adequately engage with this concept, which is central to achieving health equity and improving population health. Much work remains to be done and will require that journals, funders, and peer reviewers support scholarship to explicitly name institutionalized racism. For example, journal editors might sponsor special issues that publish and highlight novel and innovative work that names institutionalized racism. Funders might consider requiring those submitting proposals examining racial disparities to use a public health critical race praxis29 methodology or include a section that asks the researchers to describe how they will define and measure their race variable(s).

We hope that this initial review will result in future studies that more deeply review the public health literature in response to Jones’s call to action. We also hope that this review will lead to further integration of the law and justice framework for naming to further our understanding of the use of naming institutionalized racism. Finally, future research might include qualitative studies aimed at capturing information on the experience of communities in which institutionalized racism affects their health and well-being. Although institutionalized racism has begun to be named in commentary pieces, empirical work, especially original research, that explicitly names the term in the title or abstract needs to increase.8,43 Words have power, and being explicit about naming this critical construct may move the field forward in important ways.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Margaret Hicken, PhD, for her thoughtful feedback on early drafts of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Satcher D, Higginbotham EJ. The public health approach to eliminating disparities in health. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):400–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braveman P. What are health disparities and health equity? We need to be clear. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(suppl 2):5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldberg D. “Inequities” vs. “disparities”: why words matter.]https://inequalitiesblog.wordpress.com/2011/05/31/‘inequities’-vs-‘disparities’-why-words-matter. Published 2011. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 5. Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, Fryer CS, Garza MA. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:399–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smedley BD, Myers HF. Conceptual and methodological challenges for health disparities research and their policy implications. J Soc Issues. 2014;70(2):382–391. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones C. Launching an APHA presidential initiative on racism and health. Nation’s Health. 2016;45(10):3. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hardeman RR, Medina EM, Kozhimannil KB. Structural racism and supporting black lives—the role of health professionals. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2113–2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):888–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health II: a needed research agenda for effective interventions. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8). doi:10.1177/0002764213487341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Powell JA. Structural racism: building upon the insights of John Calmore. NC L Rev. 2008;86:791–816. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Alang S, McAlpine D, McCreedy E, Hardeman R. Police brutality and black health: setting the agenda for public health scholars. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):662–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jee-Lyn García J, Sharif MZ. Black lives matter: a commentary on racism and public health. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e27–e30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spiegel JM, Breilh J, Yassi A. Why language matters: insights and challenges in applying a social determination of health approach in a North-South collaborative research program. Global Health. 2015;11:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jones CP. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon. 2002;50(1):7–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18. QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo [computer software]. Version 10 Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Armstrong DL, Strogatz D, Wang R. United States coronary mortality trends and community services associated with occupational structure, among blacks and whites, 1984-1998. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2349–2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lukachko A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM. Structural racism and myocardial infarction in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:42–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wallace ME, Mendola P, Liu D, Grantz KL. Joint effects of structural racism and income inequality on small-for-gestational-age birth. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):1681–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Metzler MM, Higgins DL, Beeker CG, et al. Addressing urban health in Detroit, New York City, and Seattle through community-based participatory research partnerships. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Evans BC. Cultural and ethnic differences in content validation responses. West J Nurs Res. 2004;26(3):321–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ford ME, Kelly PA. Conceptualizing and categorizing race and ethnicity in health services research. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 pt 2):1658–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Holmes SM. An ethnographic study of the social context of migrant health in the United States. PLoS Med. 2006;3(10):e448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kramer MR, Hogue CR. What causes racial disparities in very preterm birth? A biosocial perspective. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:84–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McAllister CL, Thomas TL, Wilson PC, Green BL. Root shock revisited: perspectives of Early Head Start mothers on community and policy environments and their effects on child health, development, and school readiness. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Albert MA, Cozier Y, Ridker PM, et al. Perceptions of race/ethnic discrimination in relation to mortality among black women: results from the Black Women’s Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(10):896–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. Critical race theory, race equity, and public health: toward antiracism praxis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S30–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steinecke A, Terrell C. Progress for whose future? The impact of the Flexner Report on medical education for racial and ethnic minority physicians in the United States. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cene CW, Akers AY, Lloyd SW, Albritton T, Powell Hammond W, Corbie-Smith G. Understanding social capital and HIV risk in rural African American communities. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):737–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, et al. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):953–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2099–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chattopadhyay S, Myser C, De Vries R. Bioethics and its gatekeepers: does institutional racism exist in leading bioethics journals? J Bioeth Inq. 2013;10(1):7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hall JM, Fields B. Continuing the conversation in nursing on race and racism. Nurs Outlook. 2013;61(3):164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Purtle J. Felon disenfranchisement in the United States: a health equity perspective. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Paradies Y, Truong M, Priest N. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):364–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sabo S, Shaw S, Ingram M, et al. Everyday violence, structural racism and mistreatment at the US-Mexico border. Soc Sci Med. 2014;109:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scott HM, Pollack L, Rebchook GM, Huebner DM, Peterson J, Kegeles SM. Peer social support is associated with recent HIV testing among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):913–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weiler AM, Hergesheimer C, Brisbois B, Wittman H, Yassi A, Spiegel JM. Food sovereignty, food security and health equity: a meta-narrative mapping exercise. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(8):1078–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Felstiner WLF, Abel RL, Sarat A. The emergence and transformation of disputes: naming, blaming, claiming. Law Soc Rev. 1980. –1981;15(3/4):631–654. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Metzl JM, Roberts DE. Structural competency meets structural racism: race, politics, and the structure of medical knowledge. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(9):674–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bassett MT. #BlackLivesMatter—a challenge to the medical and public health communities. NEngl JMed. 2015;372(12):1085–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]