As of 2018, 5.5 million Americans were projected to have Alzheimer’s disease, on the basis of 2010 estimates.1 Recent national and international surveys suggest that preventing Alzheimer’s disease and preserving cognitive health are among the top concerns of those in the aging public, many of whom list dementia as their most feared disease, ahead of cancer or stroke.2-4 Consequently, many in this population are now engaging in activities that they hope will stave off cognitive impairment and diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease; some are acting on the advice of health care practitioners (eg, to manage hypertension), whereas others are responding to mainstream advertising (eg, to take vitamin supplements or engage in brain training programs). Because public health professionals are on the front lines of health education and message delivery about prevention and risk reduction, they are uniquely positioned to disseminate evidence-based information about these topics to the public. To distribute this information most effectively, they may benefit from having a working knowledge of the most recent activities related to brain health undertaken by various US government agencies. In this Executive Perspective, we describe recent federal government strategies, projects, and documents that are most relevant to Alzheimer’s disease prevention and risk reduction.

In 2011, the National Prevention Council, chaired by the US surgeon general, developed the National Prevention Strategy, which provides a framework upon which policies and projects concerning brain health could be built.5 The National Prevention Strategy envisions for the future a prevention-oriented society in which all sectors recognize the value of health for individuals, families, and society and work together to achieve better health for Americans. In 2016, the National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council published a report, Healthy Aging in Action: Advancing the National Prevention Strategy, that resulted from the once-a-decade White House Conference on Aging in 2015.6 This report built on the 2011 National Prevention Strategy by highlighting programs that are putting the strategy into action and advancing its goal of increasing the number of Americans who are healthy at every stage of life. The report is intended for a range of partners, including decision makers in federal, state, and local government; providers of services to the aging population; public health officials; and health care providers. It specifies actions that can improve health and well-being later in life, including (1) prevention efforts to enable older adults to remain active, independent, and involved in their communities; (2) innovative, evidence-based programs conducted by federal departments and agencies and local communities that address the challenges to physical, mental, emotional, and social well-being that are often encountered later in life; and (3) future multisector efforts to promote and facilitate healthy aging at the community level.

Other federal public health initiatives focus specifically on Alzheimer’s disease and brain health. The National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease, which was introduced in 2012 and is updated annually and most recently in 2017, outlines a strategy that targets Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.7 Its primary goals are to guide research into the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and to address the clinical care and service challenges faced by those who have these conditions and their caregivers. Overseen by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, in consultation with the Secretary’s Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services, the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease illustrates the importance that the federal government places on Alzheimer’s disease prevention, risk reduction, treatment, care, and services. Although the plan includes public messaging about Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias among its goals, like the National Prevention Strategy, it is meant to be a high-level strategy document, not specific actionable guidance for frontline public health professionals in their efforts to attempt to help prevent Alzheimer’s disease and maintain brain health.

However, other federal agencies provide evidence-based guidance for frontline public health professionals and others in the areas of Alzheimer’s disease and brain health. In 2013, the McKnight Brain Research Foundation, the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Retirement Research Foundation, AARP, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) commissioned the Institute of Medicine report, Cognitive Aging: Progress in Understanding and Opportunities for Action.8 Released in 2015, the report characterizes cognitive aging and provides evidence-based recommendations that individuals, families, communities, health care providers and systems, financial organizations, community groups, and public health agencies can take to help promote brain health (Box 1). Along similar lines, multiple federal agencies developed and introduced the Brain Health Resource toolkit in 2014.9 Based on the best available evidence at that time and currently being updated, the toolkit can be used by health educators in community settings to help explain how brain function changes with age and what can be done to attempt to help maintain brain health.

Box 1. Recommendation 3 from Cognitive Aging: Progress in Understanding and Opportunities for Action 8: Take Actions to Reduce Risks of Cognitive Decline With Aging

Individuals of all ages and their families should take actions to maintain and sustain their cognitive health, realizing that there is wide variability in cognitive health among individuals. Specifically, individuals should:

• Be physically active.

• Reduce and manage cardiovascular disease risk factors (including hypertension, diabetes, smoking).

• Regularly discuss and review health conditions and medications that might influence cognitive health with a health care professional.

• Take additional actions that may promote cognitive health, including:

• Be socially and intellectually engaged, and engage in lifelong learning;

• Get adequate sleep and receive treatment for sleep disorders if needed;

• Take steps to avoid the risk of cognitive changes due to delirium if hospitalized; and

• Carefully evaluate products advertised to consumers to improve cognitive health, such as medications, nutritionals, and cognitive training.

Other evidence-based guidance for the public health community has been developed. In 2010, the National Institutes of Health commissioned a literature review for a State-of-the-Science Conference on Alzheimer’s disease risk factors and interventions. Based on this review, the final conference statement concluded that evidence was insufficient to support the use of pharmaceutical agents or dietary supplements to prevent cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s disease.10 However, in 2015, the National Institute on Aging recognized that the body of literature about these topics had grown substantially since the 2010 review, and it funded a new project to explore the scientific evidence for the effectiveness of various dementia prevention strategies. The institute used a 2-step process for the project. The first step involved the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Evidence-based Practice Centers Program, which comprises several institutions that develop evidence reports and technology assessments on topics relevant to clinical, social science/behavioral, economic, and other health care organization and delivery issues. The second step involved an expert committee convened by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The committee provided a second opinion based on the standardized and rigorous literature review findings provided by the Evidence-based Practice Centers Program. The resulting report, published in 2017, indicates that among the topics explored, certain forms of cognitive training had the highest level of evidence, and physical activity emerged as an area of promise; however, caveats exist for the strength of evidence for both with respect to prevention.11 In evaluating this report, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine expert committee concluded that cognitive training, blood pressure management for those with hypertension, and increased physical activity—all practices known to be beneficial for other aspects of healthy aging—are supported by “encouraging although inconclusive evidence,” and the committee recommended pursuing additional research in these and related areas (Box 2).12

Box 2. Recommendation 1 from Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Way Forward 12: Communicating With the Public

When communicating with the public about what is currently known, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and other interested organizations should make clear that positive effects of the following classes of interventions are supported by encouraging although inconclusive evidence:

• Cognitive training—a broad set of interventions, such as those aimed at enhancing reasoning, memory, and speed of processing—to delay or slow age-related cognitive decline

• Blood pressure management for people with hypertension to prevent, delay, or slow clinical Alzheimer’s-type dementia

• Increased physical activity to delay or slow age-related cognitive decline

There is insufficient high-strength experimental evidence to justify a public health information campaign, per se, that would encourage the adoption of specific interventions to prevent these conditions. Nonetheless, it is appropriate for the National Institutes of Health and others to provide accurate information about the potential impact of these 3 intervention classes on cognitive outcomes in a place where people can access it (eg, websites). It also is appropriate for public health practitioners and health care providers to include mention of the potential cognitive benefits of these interventions when promoting their adoption for the prevention or control of other diseases and conditions.

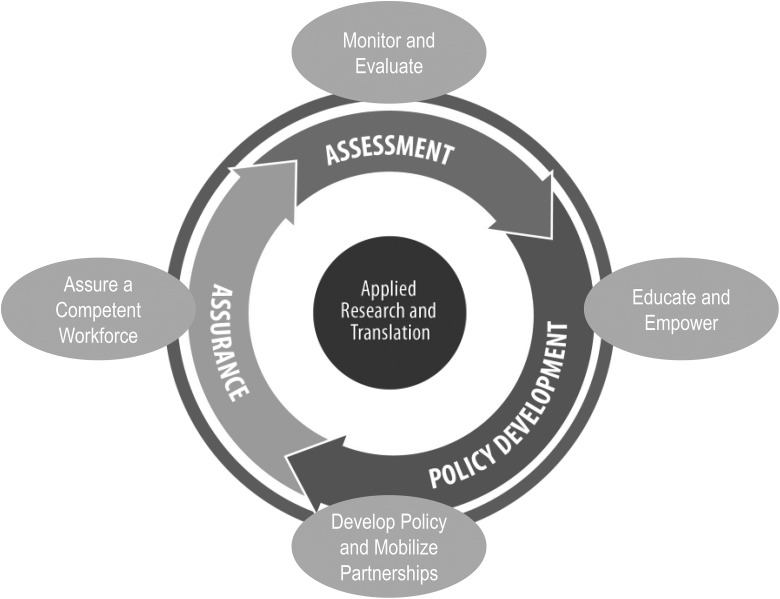

Federal agencies have also developed programs to deliver public health messages on brain health to public health professionals. In 2005, the Alzheimer’s Association and CDC partnered to create the Healthy Brain Initiative to address cognitive health from a public health perspective and catalyze action by state and local public health professionals. The most recent publication resulting from this initiative, Healthy Brain Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013-2018, was released in 2013 and was designed to complement the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease.13 This report identified 35 actions that state and local public health agencies and their partners can take to promote cognitive health and the needs of caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. The publication categorizes these actions into the 4 traditional domains of public health: monitor and evaluate, educate and empower the nation, develop policy and mobilize partnerships, and assure a competent workforce (Figure). To accomplish some of these actions, CDC has funded partners, including the Alzheimer’s Association, The Balm In Gilead (developer of educational and training programs designed to meet the needs of African American church congregations striving to become community centers for health education and disease prevention), and the Healthy Brain Research Network (6 members of the consortium of 24 CDC Prevention Research Centers, which study how people and their communities can avoid or counter the risks for chronic illnesses). A Healthy Brain Initiative progress report15 and dissemination guide,16 both released in 2015, highlight selected Road Map action accomplishments and suggest future directions for communities. The Road Map is now under revision again and new action items will be released in 2018, with an emphasis on Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, diagnosis disclosure, risk reduction, and caregiving.

Figure.

Conceptual framework for cognitive health actions, with linking to core functions of public health. The conceptual framework integrates the 3 public health core functions14 with applied research and translation, and it was used to identify 35 actions within the 4 traditional domains of public health that state and local public health agencies and their partners can take to promote cognitive health and the needs of caregivers. Data source: reprinted from The Healthy Brain Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013-2018.13

Furthermore, CDC, together with other partners, is working to implement additional action items from the Road Map, with particular emphasis on the goal to “educate and empower the nation.” For example, CDC is partnering with the Healthy Brain Research Center at the University of Pennsylvania, initiating a project that involves sending out a series of research-tested messages (currently being tested in various audiences) targeted to adult children, encouraging them to accompany parents to health care appointments if they have concerns about parental memory.17 CDC is also partnering with The Balm In Gilead to inform African American nurses and physicians about the importance of brain health and caregiving and to raise awareness of Alzheimer’s disease and brain health in African American faith-based communities through Memory Sunday.18 This event, which occurs on the second Sunday in June, provides education on Alzheimer’s disease prevention, treatment, research studies, and caregiving. In addition, CDC is partnering with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors to undertake action items from the Road Map that affect their constituencies in selected US states.

Finally, CDC is also making data available to public health professionals and policy and program decision makers at the national, regional, and state levels. Through its Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System,19 CDC is providing annual data on both cognitive decline and caregiving surveillance. In addition, CDC launched the Healthy Aging Data Portal,20 which provides public health professionals with access to a range of national, regional, and state health-related data on older adults. Users can access data on key indicators of health and well-being of older Americans, such as tobacco and alcohol use, screenings and vaccinations, mental and cognitive health, and caregiving. The portal enables public health professionals and policy makers to examine snapshots of the health of older adults in their regions or states to prioritize and evaluate public health interventions.

Public health professionals are uniquely positioned to use evidence-based information and surveillance data at the federal, state, and local levels to help Americans optimize brain health. They have an opportunity to use and disseminate materials and tools provided by federal agencies and their partners to foster better understanding of the risks of cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease and of the strategies that may help reduce those risks, while they wait for more definitive answers from the research community.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Vicky Cahan for her helpful review of this article. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010-2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. AARP. Findings from AARP’s 2012 Member Opinion Survey (MOS). http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/general/2013/Findings-from-AARP-2012-Member-Opinion-Survey-AARP.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed September 27, 2017.

- 3. Dementia more feared than cancer new Saga survey reveals [news release]. Kent, UK: Saga; May 17, 2016 https://www.saga.co.uk/newsroom/press-releases/2016/may/older-people-fear-dementia-more-than-cancer-new-saga-survey-reveals.aspx. Accessed September 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alzheimer’s most feared disease [news release]. Poughkeepsie, NY: Marist Institute for Public Opinion; November 15, 2012 http://maristpoll.marist.edu/1114-alzheimers-most-feared-disease. Accessed September 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. US Department of Health and Human Services. National prevention strategy. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/index.html . Published 2011. Accessed September 27, 2017.

- 6. National Prevention Council. Healthy Aging in Action: Advancing the National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2016. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/about/healthy-aging-in-action-final.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease: 2017 Update. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Institute of Medicine. Cognitive Aging: Progress in Understanding and Opportunities for Action. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Institute on Aging. Brain health resource. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/brain-health-resource . Published 2014. Accessed October 5, 2017.

- 10. Daviglus ML, Bell CC, Berrettini W, et al. NIH state-of-the-science conference statement: preventing Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2010;27(4):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kane RL, Butler M, Fink HA, et al. Interventions to Prevent Age-Related Cognitive Decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Clinical Alzheimer’s-Type Dementia. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 188 Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Way Forward. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alzheimer’s Association and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Healthy Brain Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013-2018. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Healthy Brain Initiative: The Public Health Road Map for State and National Partnerships, 2013-2018: Interim Progress Report. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dissemination Guide: The Healthy Brain Initiative—Interim Progress Report (2013-2018). Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karlawish J. Developing culturally-relevant media messages for adult children with concerns about an aging parent. Gerontologist. 2016;56(suppl 3):226. [Google Scholar]

- 18. The Balm In Gilead. National Brain Health Center for African Americans. http://brainhealthcenterforafricanamericans.org/memory-sunday . Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html . Published 2017. Accessed January 24, 2018.

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy aging data. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/agingdata/index.html . Published 2017. Accessed October 2, 2017.