Abstract

Introduction:

Colorectal cancer (CRC) has different forms of colon cancer or rectal cancer. CRCs are often considered together because they possess many similar features. A severe form of the disease with higher mortality rate increases with increase in age. The most common CRC risk factors include smoking, diabetes, and obesity. This study aims to evaluate the awareness of CRC in a random population of Asir region and to identify the subpopulation that can be recipients of awareness and screening programs.

Material and Methods:

Cross-sectional nonprobable random sampling study using a self-administered questionnaire survey which was employed to include healthy males and females from Asir region. The questionnaire included ten questions in Arabic language and data were categorized according to gender, marital status, age, and level of education to determine whether these demographic groups possess difference in knowledge about CRC.

Results:

Most of the respondents (51% and 71.6%) knew what is colon and rectum. About 33.8% know the correct function of the colon while 22.5% know the correct incidence and 22.1% know the correct time of screening for CRC. Very few respondents know the symptoms, risks, and screening modalities of CRC. Pearson's Chi-square test was employed to evaluate the differences in responses in four demographic categories of the study population. P <0.05 was considered as statistically significant

Conclusions:

Single less educated males lack knowledge of CRC. In addition, there is very low awareness of CRC symptoms, risk factors, and screening modalities among the entire surveyed population.

Keywords: Awareness, colorectal cancer, screening

Introduction

According to the American Cancer Society, colorectal cancer (CRC) represents any cancer that occurs in the rectum or colon (https://www.cancer.org). Depending on where they start, CRC has different forms of colon cancer or rectal cancer. CRCs are often considered together because they possess many similar features. They are usually adenocarcinomas that begin as precancerous polyps that grow on the inner lining of the rectal or colon wall. Some polyps become malignant over time but not all polyps become cancer. Both the polyps and early-stage CRCs usually present without symptoms leading to a delay in diagnosis.

A severe form of the disease with higher mortality rate increases with increase in age. The most common CRC risk factors include smoking, diabetes, and obesity. CRC is the second most common cause of cancer-related death in United States.[1] They are the third most common cancer in the world[2] and the second most common cancer in Saudi Arabia.[3] They exhibit gender predilection, being more common in Saudi males than Saudi females (http://www.chs.gov.sa). They are most prevalent in North America and Europe[4] and less prevalent in South America, Africa, and Asia.[5] This significant variation of prevalence is attributed to the risk factors that are commonly associated with “Western” Culture.[4] Hence, countries predisposed to risk factors in addition to huge young population are likely to possess higher incidence of CRC.

Saudi Arabia has a huge young population with risk factors of CRC which presents a major health risk. Moreover, the survival rate of Saudi CRC patients is considerably lower than the survival rate of patients from the United States. A sharp increase in incidence over the years has been reported in Saudi patients.[6] Like any other malignancy, the survival rate of CRC patients depends mainly on the clinical/pathological stage at the time of diagnosis. Awareness and preventive screening programs play a vital role in early diagnosis and improving the survival rate of such patients. It has been reported that the awareness of a disease among the public is directly related to the screening program participation. Zubaidi et al. reported a lack of correct knowledge and presence of misconceptions regarding the understanding of CRC in general public of Riyadh region.[6] In Lebanon, Hejase et al. reported lack of knowledge on CRC where the percentage of respondents that has never heard about it exceeds 59%;[7] Mhaidat et al.on his cross-sectional study among University Students in Jordan found that 14.3% of responders experienced poor knowledge, 52.9% have fair knowledge, and 32.8% have good knowledge.[8] In the Jamaican population, Lee MG et al. found that 14% of the population had no knowledge about CRC, 69% did not know enough, and 17% knew about it.[9] The aim of this study was to evaluate the awareness of general understanding of CRC in a population of Asir region. A secondary aim of the study was to identify the subpopulation in Asir region that can be specifically targeted for awareness and screening programs. This will help in planning for more effective and successful screening programs that are designed for the needs of Asir population.

Materials and Methods

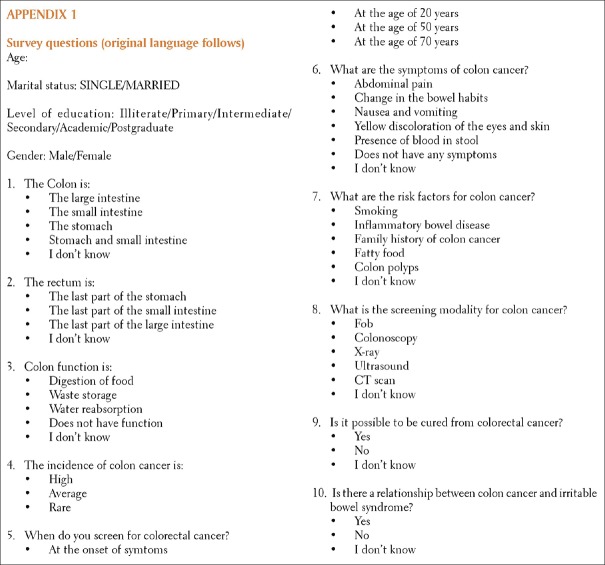

A cross-sectional study design with nonprobable convenient sampling was employed using self-administered questionnaire survey in the Arabic language [Figure 1] with minor modifications to Zubaidi et al. [Figure 2][6] questions. Ethics approval was obtained from King Khalid University, College of Medicine and an ethical review board of Research Ethics Committee. The survey was conducted between December 2016 and May 2017 electronically as well as in printed form. The questionnaire consisted of 10 multiple choice questions related to the risks factors, symptoms, screening, treatment, and prognosis of CRC. An information pamphlet in the Arabic language was also included to provide the participants a brief account of the main purpose of the study and instructions on how to answer the questions. The participants were instructed to select multiple answers wherever appropriate. Only residents from Asir region that were not related to the field of medicine were invited to participate in the survey. Only males and females older than 10 years without any history of CRC or inflammatory bowel disease (irritable bowel syndrome [IBS]) were included. Anonymous personal and demographic data including the age, gender, marital status, place of residence, and education level of the participants were recorded. Education level and age of the participants were categorized according to Zubaidi et al[6] criteria. Data obtained were statistically analyzed by Pearson's Chi-square test using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.005 was considered as statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Arabic translated self administered questionnaire

Figure 2.

The questionnaire that was used by Zubaidi et al

Results

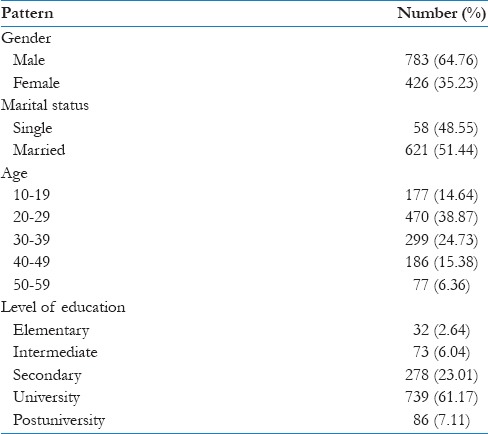

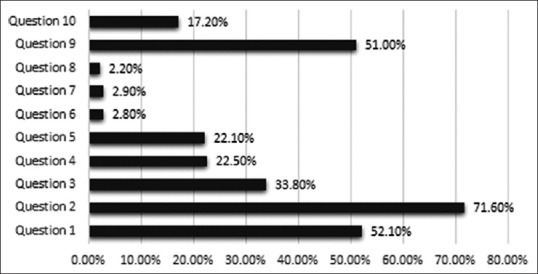

Table 1 presents the demographic distribution of the survey participants. One thousand two hundred and nine people responded to the survey, out of which 64.76% were males and 35.23% were females. Almost one-third (64.76%) of the respondents were married, 38.87% belonged to the age of a group of 20–29 years, and 61.17% had university level of education. Almost half of the respondents (51% and 52.1%) answered questions 1 and 9 correctly. They seemed to be most knowledgeable about question 2 since two-thirds (71.6%) of them answered it correctly. Only one-third of them (33.8%) seem to know the correct function of the colon (Question 3). The correct response percentage for questions 4 and 5 was very similar (22.5% and 22.1%, respectively) while the correct response percentage for question 10 was 17.2% only. A very low percentage of correct responses was received for questions 6, 7, and 8 [Figure 3].

Table 1.

Demographics of survey participants

Figure 3.

Percentage of correct response

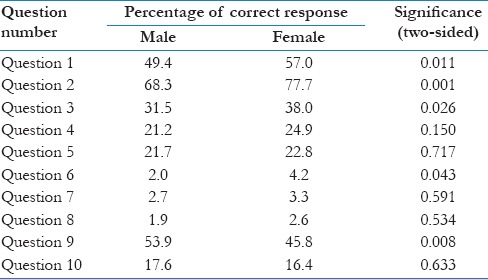

Gender

Overall, female respondents were more knowledgeable than male respondents regarding CRC [Table 2]. The percentage of correct answers selected by females were more for all the questions except question 9 (cure of CRC?) and 10 (relationship of CRC and IBS). A statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) in responses of males and female s was present for question 2(what is rectum?).

Table 2.

Pearson's Chi-square analysis of survey responses according to gender

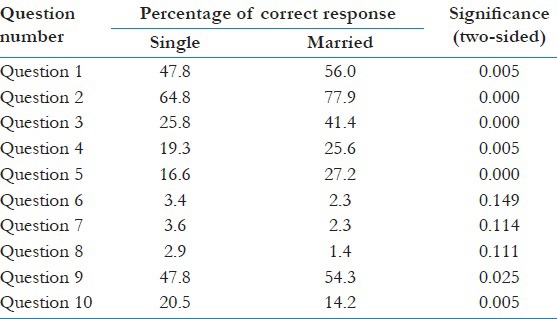

Marital status

Married respondents answered all survey questions more correctly, except questions 6, 7, 8, and 10, than single respondents did [Table 3]. A statistically significant difference between the responses of married and single participants is present for all questions except question 6, 7, 8, and 9. Correct response percentage for questions 6, 7, and 8 was very low.

Table 3.

Pearson's Chi-square analysis of survey responses according to marital status

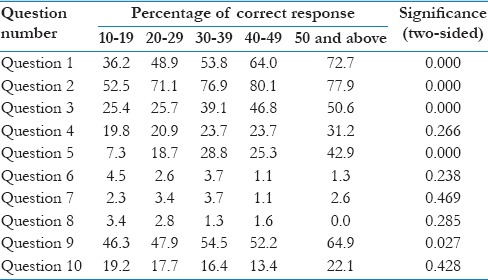

Age group

The participants were divided into five groups based on their age. All the five groups provided very low percentage of the correct answer for question 6, 7, and 8 [Table 4]. Respondents belonging to the age group of 50–59 years answered all survey question more correctly except question 8 (screening modality of CRC?) than the respondents of other age groups. Statistical significance was observed for questions 1, 2, 3, and 5.

Table 4.

Pearson's Chi-square analysis of survey responses according to age groups

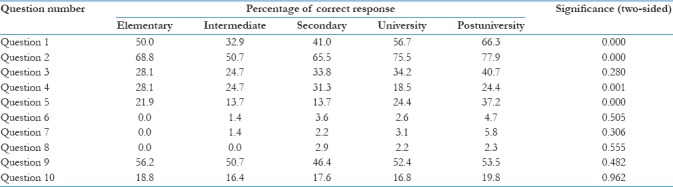

Level of education

In general, postuniversity respondents were more knowledgeable about CRC than the remaining groups based on the level of education [Table 5]. Statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed for questions 1, 2, and 4. Similarly, correct response percentage for questions 6, 7, and 8 was very low.

Table 5.

Pearson's Chi-square analysis of survey responses according to age in years

Discussion

The level of awareness among the public regarding CRC remains uncertain globally. To the best of our knowledge, no other study has evaluated similar subject in this region except for Zubaidi et al. who have explored a cross-sectional population in Riyadh region. They reported limited awareness of CRC among young single low educated men.[6] They also recommended carrying out similar awareness surveys in other regions of Saudi Arabia. This recommendation became the basis of our study, and hence, the awareness of CRC among people of different age groups, levels of education, and genders in Asir region of Saudi Arabia was evaluated. Like other similar studies,[10,11,12,13] our study too revealed very low knowledge of CRC among surveyed population. In general, females, married, respondents above 50 years of age, and postuniversity educated respondents were more knowledgeable than the other respondents of the survey were. This is in confirmation with the results of Zubaidi et al.[6] study. It is strange to note that women are more knowledgeable regarding CRC than men are, though CRC is more common in men.[14] This may be because women tend to be more concerned than men about their health. For instance, according to a report, women are more likely to seek medical consultation for simple health issues like a headache.[15] In addition, there is a well-known gender bias toward men in terms of the support received from their families, forcing women to equip themselves with knowledge of their well-being.[16] However, in our survey, the only question that men answered more correctly was regarding the relationship of CRC and IBS. Moreover, as pointed by Zubaidi et al.,[6] females may have imparted their knowledge to their spouses; hence, married respondents were more aware of CRC than single respondents. It was obvious to note that older and postuniversity respondents were generally more aware of CRC than less educated younger respondents.

The salient outcome of the survey was the extreme lack of knowledge of the respondents regarding CRC symptoms, risk factors, and screening modalities. In our opinion, these were the key aspects of the questionnaire that would decide its overall result. The remaining questions were rather general and can be answered with general knowledge of human body. Older married postuniversity females also fared poorly in these key areas. In addition to this, the general response to questions regarding incidence and screening time of CRC was also low. Although the present survey shows females, older individuals, and the higher educated to be more knowledgeable, educational programs should be aimed at every individual, male or female, and educated or not educated to increase the knowledge of those most at risk.

Many methods of improving CRC awareness among the general population have been reported in the literature.[17,18,19,20] Some have been more effective than others, and in our opinion, the best method depends on the nature and demographics of the population. A national screening program involving social media platforms, sports, and cultural events can be effective in spreading awareness. In the end, this study had few limitations that need to be reported. The percentage of elementary, intermediate, and postuniversity educated participants was very low. Likewise, male participants were considerably more than female participants that may have created a bias. Nevertheless, it seems imperative to conduct larger awareness programs including all the major regions of the country to generalize the results presented in this study.

Conclusions

The subgroups of the study population with less knowledge of CRC included unmarried, low educated males. In addition, there is an extreme lack of awareness regarding CRC symptoms, risk factors, and screening modalities among the entire surveyed population. Therefore, we recommend awareness and screening programs to be conducted for all the citizens irrespective of their demographics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Basic Information about Colorectal Cancer Atlanta. GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention CfDCa. 2014. [Last accessed on 2014 Jul 11]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/index.htm .

- 2.Colorectal cancer statistics | World Cancer Research Fund International. 2012. [Last cited on 2017 Oct 5]. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.wcrf.org/int/cancer-facts-figures/data-specific-cancers/colorectal-cancer-statistics .

- 3.Al-Ahwal MS, Shafik YH, Al-Ahwal HM. First national survival data for colorectal cancer among Saudis between 1994 and 2004: What's next? BMC Public Health. 2013;13:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: Incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:191–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center MM, Jemal A, Smith RA, Ward E. Worldwide variations in colorectal cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:366–78. doi: 10.3322/caac.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zubaidi AM, AlSubaie NM, AlHumaid AA, Shaik SA, AlKhayal KA, AlObeed OA, et al. Public awareness of colorectal cancer in Saudi Arabia: A survey of 1070 participants in Riyadh. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:78–83. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.153819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hejase AJ, Hejase HJ, Nemer HA, Othman M, Chawraba M, Trad MA. Colorectal cancer: Exploring awareness in Lebanon. J Middle East North Afr Sci. 2016;2:10–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mhaidat NM, Al-husein BA, Alzoubi KH, Hatamleh DI, Khader Y, Matalqah S, et al. Knowledge and Awareness of Colorectal Cancer Early Warning Signs and Risk Factors among University Students in Jordan. Journal of Cancer Education. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1142-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee MG, Brown EF, Mills MO, Walters CA. Colon Cancer Screening: Knowledge and Attitudes in a Jamaican Population and Physicians. World Journal of Research and Review. 2017;4(5):04–07. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McVeigh TP, Lowery AJ, Waldron RM, Mahmood A, Barry K. Assessing awareness of colorectal cancer symptoms and screening in a peripheral colorectal surgical unit: A survey based study. BMC Surg. 2013;13:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohd Suan MA, Mohammed NS, Abu Hassan MR. Colorectal cancer awareness and screening preference: A Survey during the Malaysian world digestive day campaign. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:8345–9. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.18.8345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harewood GC, Murray F, Patchett S, Garcia L, Leong WL, Lim YT, et al. Assessment of colorectal cancer knowledge and patient attitudes towards screening: Is Ireland ready to embrace colon cancer screening? Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178:7–12. doi: 10.1007/s11845-008-0163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibrahim EM, Zeeneldin AA, El-Khodary TR, Al-Gahmi AM, Bin Sadiq BM. Past, present and future of colorectal cancer in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:178–82. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.43275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy G, Devesa SS, Cross AJ, Inskip PD, McGlynn KA, Cook MB, et al. Sex disparities in colorectal cancer incidence by anatomic subsite, race and age. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:1668–75. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt K, Adamson J, Hewitt C, Nazareth I. Do women consult more than men. A review of gender and consultation for back pain and headache? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16:108–17. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vlassoff C. Gender differences in determinants and consequences of health and illness. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:47–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenwald B. Health fairs: An avenue for colon health promotion in the community. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26:191–4. doi: 10.1097/00001610-200309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bagai A, Parsons K, Malone B, Fantino J, Paszat L, Rabeneck L, et al. Workplace colorectal cancer-screening awareness programs: An adjunct to primary care practice? J Community Health. 2007;32:157–67. doi: 10.1007/s10900-006-9042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redwood D, Provost E, Asay E, Ferguson J, Muller J. Giant inflatable colon and community knowledge, intention, and social support for colorectal cancer screening. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E40. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanchez JI, Palacios R, Cole A, O'Connell MA. Evaluation of the walk-through inflatable colon as a colorectal cancer education tool: Results from a pre and post research design. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:626. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]