Abstract

In patients with endometrial cancer, the expression and prognostic significance of calreticulin (CRT) remains to be fully elucidated. To investigate the role of CRT in endometrial cancer, the present study compared its expression status with clinicopathological characteristics and evaluated its prognostic significance. The expression of CRT, PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (p-eIF2α), and Ki67 were assessed by immunohistochemistry and/or western blotting in endometrial cancer patients. The association of the expression of CRT, p-eIF2α and Ki67 with patient survival rate was assessed by Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses. Low levels of CRT and an overexpression of Ki67 were significantly associated with the stage, histology, and differentiation of the primary surgery without doxorubicin (DOX) neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) patient group and were significantly correlated with a short progression-free survival and the overall survival. A multivariate analysis revealed that CRT and Ki67 expression were independent prognostic indicators for endometrioid endometrial cancer. Low CRT expression and an overexpression of Ki67 were significantly associated with DOX-NAC and the histology (P<0.05) pre-NAC and post-NAC in the DOX-NAC patient group. Upon treatment of DOX-NAC, CRT, PERK and p-eIF2α protein content were overexpressed in DOX-sensitive endometrial cancer (P<0.05), whereas there was no significant difference in the DOX-resistant group. Low CRT expression in endometrial cancer is significantly associated with aggressive progression and poor prognosis. CRT may therefore serve as a molecular marker for predicting the progression and prognosis in DOX-resistant endometrial cancer patients.

Keywords: calreticulin/phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α/doxorubicin-resisitant/endometrial cancer/prognostic biomarker

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most commonly diagnosed gynecologic malignancy in the United States. In 2015, approximately 55,000 new cases (7% of total cancer cases) and approximately 10,000 deaths (4% of total cancer deaths) were reported (1), and this same trend was also observed in China (2). The epidemiology of endometrial cancer is multifactorial. The most common risk factors associated with the development of endometrial cancer are unopposed estrogen exposure and obesity (endometrioid endometrial cancer). A smaller subset of sporadic cancers is associated with aging and unique genetic/molecular changes, producing a more aggressive variant, serous/clear cell type (non-endometrioid endometrial cancer) (3). For patients with advanced endometrial cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) is recommended. The standard first-line therapy consists of cisplatin (CDDP) and a doxorubicin (DOX) ± paclitaxel combination and/or carboplatin plus paclitaxel (4). Understanding the process of tumor resistance is critical, and defining which patients are more likely to respond to the established or novel therapies is our greatest challenge.

Calreticulin (CRT) is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident protein that is critical for maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis and glycoprotein folding in the ER. CRT was identified on the cell surface of apoptotic and necrotic cells and plays a role in immunogenic cell death (ICD) and other extracellular functions (5). The ER responds to stress by activating an adaptive mechanism called the unfolded protein response (UPR). Three distinct sensors activate the UPR: i) Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) (an ER kinase and endoribonuclease); ii) activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6); and iii) PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). The activation of PERK leads to the attenuation of global protein translation via the phosphorylation and inhibition of the α subunit of eIF2α. However, the inhibition of IRE1 and ATF6 does not affect the expression of ecto-CRT on the plasma membrane (6), suggesting that the PERK pathway is the key UPR sensor involved in chemotherapy-induced ICD. Activated PERK is considered a classical precursor for ICD-associated ecto-CRT expression in vitro and ICD in vivo, but the activation of PERK alone does not always result in increased ecto-CRT (7). This suggests that ER stress is required to induce the ICD-associated translocation of CRT to the cell surface. The ecto-CRT serves as a potent ‘eat me’ signal for local patrolling dendritic cells (DCs).

CRT is recognized as a protein that alters tumor growth. High CRT expression, which is likely driven by an ER stress response, constitutes a positive prognostic biomarker in NSCLC patients. The local presence of CRT in a constitutively expressed manner at the surface of transformed epithelial cells might enable DC-dependent anticancer immunosurveillance (8). On the contrary, a high expression of CRT and 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) was correlated with a poor prognosis by a Kaplan-Meier analysis and a log rank analysis in Chinese esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (9). A higher cellular CRT protein expression in effusions is associated with a better response to chemotherapy at diagnosis in high-grade ovarian serous carcinoma (10). Recent studies demonstrate that the therapeutic outcome following specific chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., anthracyclines) correlates strongly with the ability of the drugs to induce a process of ICD in cancer cells. Extensive studies reveal that chemotherapy-induced ICD occurs via the exposure/release of CRT, ATP, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10), and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) (11). Chemotherapy resistance and tumor escape from the host immunosurveillance system are the main reasons that anthracycline-based regimens in breast cancer fail, and an effective chemo-immunosensitizing strategy is lacking.

To date, no studies have demonstrated an association between CRT overexpression and the overall survival of patients with endometrial cancer. The expression of CRT in endometrial cancer with DOX-NAC is still unknown. In the present study, we performed a retrospective investigation of the association between CRT, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (p-eIF2α), and Ki67 overexpression, clinicopathological parameters, and progression-free and overall survival in patients with endometrial cancer. In addition, the relationship between the expression of CRT, PERK, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 and clinicopathological parameters were investigated in a cohort of patients with endometrial cancer receiving DOX-NAC.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue collection

Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fujian Cancer Hospital, which is affiliated with the Fujian Medical University in China. Informed consent was obtained from each patient in groups A and B for the use of tissues for the study. In group A, the samples from the 105 patients with endometrial cancer who have not received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy were collected between 2009 and 2010 for IHC analysis. All patients were followed up until December 2014 or death. The Group A is retrospective study. No prior radiation therapy or chemotherapy before surgery was allowed in group A.

In group B, 66 patients with advanced endometrial cancer were collected between 2012 and 2015 for IHC analysis. Group B is prospective study. In group B, the NAC was DOX 50–60 mg/m2 D1 every 3 weeks for 2 cycles. Patients were classified as having DOX sensitive or resistant tumors to the chemotherapy they received in the first cycle if they achieved ≥25 or <25% reduction in tumor dimensions by MRI, respectively (12). All the patients after DOX-NAC were operated in our hospital.

All the patients in Group A and B were screened for eligibility after surgery consisting of hysterectomy (total or modified radical or radical), bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy and/or para-aortic lymphadenectomy, and adequate surgical staging no more than eight weeks prior to the start of radiation therapy in both groups. All patients were required to have normal hematological, liver, and renal function with laboratory parameters being within the normal range (including a creatinine clearance ≥40 ml/min, leucocytes ≥4.0×109/l, platelets ≥100×109/l and hemoglobin ≥10 g/dl). Patients suffering from a secondary malignancy, serious concomitant systemic disorders or psychiatric disease were excluded from the study.

In group A, we focused on the relationship between the expression of CRT, p-eIF2a, Ki67 and the clinicopathological features and survival of endometrial cancer patients. In group B, we focused on the relationship of the expression of CRT, p-eIF2a, Ki67 and the sensitivity of endometrial cancer to DOX.

Fresh endometrial cancer tissue samples of twenty-four patients from pre- and post-treatment of DOX-NAC were collected for the western blot analysis. Twelve of the samples were DOX-resistant tissues and another 12 were DOX-sensitive.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of the protocol was progression-free survival (PFS). PFS was defined as the time from the date of enrollment to the date of disease progression or death from any cause. The secondary endpoints included local-regional failure, distant failure, and overall survival (OS).

Reagents

Primary antibodies against CRT (MAB3898), p-eIF2a (AF705) and PERK (AF3999) were purchased from R&D systems. Primary antibodies against Ki67 (ab15580), and β-Actin (ab8226) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

IHC assays were performed on formalin-fixed and paraffinembedded sections. Sections (thickness=5 µm) were cut and deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated a graded series of alcohols. The avidin-biotin complex method was used throughout the whole IHC procedure. Antigen retrieval was performed using a steamer for 20 min in a 1xethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 20 min. A 5% solution of nonfat milk was used to block the reaction (1 h). The slides were then incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against human CRT (1:50 dilution), p-eIF2α (1:50 dilution), or Ki67 (1:100 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the slides were reacted with the MaxVision™ HRP-polymer anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody and was counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin following staining with diaminobenzidine. The mean value of the densitometric units of five visual fields was used to rate the intensity of the expression of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67. The tumor cells with membranous or cytoplasmic staining were considered positive for expression of CRT and p-eIF2α. The tumor cells with nuclear staining was considered positive for expression of Ki67 (Fig. 1). As the negative control of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67, distilled water were used instead of primary antibody. The digital images of five representative visual fields from each slide that were positive for CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Bethesda, MD, USA). As positive controls, colon cancer for CRT and breast cancer for p-eIF2a were used, respectively. The IHC-stained tissue sections were reviewed and scored separately by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical parameters. The staining intensity was scored on a four-point scale that ranged from (−) to (+++) and was read as negative (−), <10%; weak (+), 10–25%; medium (++), 26–50%; or strong (+++), ≥50%. The percentage of positive cells was calculated by counting the number of positively stained cells showing immunoreactivity on the cell membranes and/or cytoplasm in 10 representative microscopic fields.

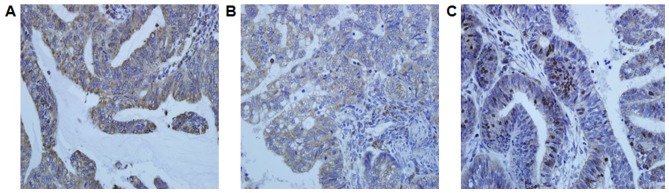

Figure 1.

Representative photomicrographs of immunohistochemical staining of endometrial cancer specimens with anti-CRT, p-eIF2a, and Ki67 antibody. Immunostaining for (A) CRT, (B) p-eIF2a, and (C) Ki67 in endometrial cancer cells. CRT, calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α.

Western blot analysis

The samples were lysed with a radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 100-M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and the protein concentrations were determined using a bicinchoninic acid kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Equal amounts of total protein were separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and were then transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were immunoblotted with the appropriate primary antibody that was diluted in tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 5% nonfat dry milk at room temperature for 2 h. After extensive washing, the membranes were incubated with an HRP-labeled antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were revealed by ECL detection. CT26 cells was used as positive control of CRT and p-eIF2a (6).

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Correlations between the expression levels were studied using the spearman coefficient. The chi-square test was used to compare between the groups. Survival curves were calculated according to the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log-rank test was used to analyze the differences between the curves. The relative influence of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 on PFS and OS was examined using a multivariate analysis according to the nonparametric hazards model of Cox. Significance was set at P<0.05. The data from the Western blot analysis was expressed as the mean ± standard deviations from at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using a Student's t-test and a one-way analysis of variance. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Immunoreactivity of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 in endometrial cancer

Group A: Tissue specimens from 105 endometrial cancer patients were examined for the expression of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 using IHC. CRT and p-eIF2α were noted in the cytoplasm and cell membrane of the tumor cells, and Ki67 was mainly observed in the nucleus (Fig. 1). CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 were highly expressed in 78 (74.3%), 62 (59.0%), and 36 of the 105 cases (34.3%), respectively (Table I). There was no significant relationship between the expression of CRT and p-eIF2α.

Table I.

Relationship between CRT, p-eIF2a, Ki67 expression and clinicopathological features of endometrial cancer.

| Clinical features | n | CRT (−/+) | CRT (++-+++) | P-value | p-eIF2a (−/+) | p-eIF2a (++-+++) | P | Ki67 (−/+) | Ki67 (++-+++) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 105 | 27 | 78 | 43 | 62 | 69 | 36 | ||||

| Age | 0.368 | 0.836 | 0.462 | |||||||

| ≤45 | 28 | 8 | 20 | 11 | 17 | 20 | 8 | |||

| >45 | 77 | 19 | 58 | 32 | 45 | 49 | 28 | |||

| Clinical stage (FIGO) | 0.001a | 0.877 | 0.010a | |||||||

| I | 29 | 4 | 25 | 11 | 18 | 22 | 7 | |||

| II | 35 | 6 | 29 | 15 | 20 | 26 | 9 | |||

| III | 25 | 7 | 18 | 11 | 14 | 15 | 10 | |||

| IV | 16 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 10 | |||

| Histology | <0.001a | 0.699 | 0.019a | |||||||

| Non-endometrioid | 31 | 13 | 18 | 12 | 19 | 16 | 15 | |||

| Endometrioid | 74 | 14 | 60 | 31 | 43 | 53 | 21 | |||

| Lymphnode metastasis | 0.056 | 0.496 | 0.269 | |||||||

| Positive | 28 | 11 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 16 | 12 | |||

| Negative | 77 | 16 | 61 | 30 | 47 | 53 | 24 | |||

| Differentiation | 0.001a | 0.689 | 0.018a | |||||||

| G1 | 28 | 3 | 25 | 13 | 15 | 22 | 6 | |||

| G2 | 40 | 7 | 33 | 15 | 25 | 28 | 12 | |||

| G3 | 37 | 17 | 20 | 15 | 22 | 19 | 18 | |||

| Muscle invasion | 0.404 | 0.728 | 0.306 | |||||||

| >1/2 | 54 | 12 | 42 | 23 | 31 | 38 | 16 | |||

| ≤1/2 | 51 | 15 | 36 | 20 | 31 | 31 | 20 | |||

| CRT | 0.201 | |||||||||

| (−/+) | 27 | / | / | / | / | 15 | 12 | |||

| (++/+++) | 78 | / | / | / | / | 54 | 24 | |||

| p-eIF-2a | 0.672 | / | 0.759 | |||||||

| (−/+) | 43 | 12 | 31 | / | / | 29 | 14 | |||

| (++/+++) | 62 | 15 | 47 | / | / | 40 | 22 |

Bold values arestatistically significant with P<0.05. CRT; calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α.

Group B: Tissue specimens from 66 advanced endometrial cancer patients receiving DOX-NAC were examined by IHC for the expression of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67. CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 were highly expressed in 36 (54.5%), 66 (48.5%), and in 29 of the 66 cases (39.4%), respectively (Table II), before NAC. There was a significant difference in the CRT (P=0.001), p-eIF2α (P=0.029), Ki67 (P=0.005) expressions between the pre-NAC and post-NAC. CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 were highly expressed in 48 (72.7%), 43 (65.1%), and in 24 of the 66 cases (36.4%), respectively (Table III), after NAC.

Table II.

Relationship between CRT, eIF-2a, Ki67 expression and clinicopathological features of endometrial carcinoma patients with NAC.

| Clinical features | n | pre-NAC CRT (−/+) | pre-NAC CRT (++-+++) | P-value | pre-NAC p-eIF2a (−/+) | pre-NAC p-eIF2a (++-+++) | P-value | pre-NAC Ki67 (−/+) | pre-NAC ki67 (++-+++) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66 | 30 | 36 | 34 | 32 | 37 | 29 | ||||

| NAC | <0.001a | 0.058 | 0.019a | |||||||

| Sensitivity | 40 | 11 | 29 | 17 | 23 | 27 | 13 | |||

| Resistance | 26 | 19 | 7 | 17 | 9 | 10 | 16 | |||

| Histology | 0.001a | 0.163 | 0.043a | |||||||

| Non-endometrioid | 17 | 14 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 11 | |||

| Endometrioid | 49 | 16 | 33 | 23 | 26 | 31 | 18 | |||

| Lymphnode metastasis | 0.418 | 0.281 | 0.492 | |||||||

| Positive | 24 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 10 | |||

| Negative | 42 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 19 | |||

| Differentiation | 0.171 | 0.424 | 0.101 | |||||||

| G1 | 25 | 9 | 16 | 12 | 13 | 17 | 8 | |||

| G2, G3 | 41 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 21 | |||

| Muscle invasion | 0.187 | 0.23 | 0.161 | |||||||

| >1/2 | 33 | 12 | 21 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 12 | |||

| ≤1/2 | 33 | 18 | 15 | 19 | 14 | 16 | 17 | |||

| pre-NAC p-eIF2a | 0.491 | / | 0.238 | |||||||

| (−/+) | 34 | 16 | 18 | / | / | 21 | 13 | |||

| (++/+++) | 32 | 14 | 18 | / | / | 16 | 16 | |||

| post-NAC CRT | 0.001a | / | / | |||||||

| (−/+) | 20 | 16 | 4 | / | / | / | / | |||

| (++/+++) | 46 | 14 | 32 | / | / | / | / | |||

| post-NAC p-eIF2a | / | 0.029a | / | |||||||

| (−/+) | 23 | / | / | 16 | 7 | / | / | |||

| (++/+++) | 43 | / | / | 18 | 25 | / | / | |||

| post-NAC Ki67 | / | / | 0.005a | |||||||

| (−/+) | 42 | / | / | / | / | 29 | 13 | |||

| (++/+++) | 24 | / | / | / | / | 8 | 16 |

P<0.05. NAC, neoadjuvant chemothereapy; pre-NAC, prior to the neoadjuvant chemotherapy; post-NAC, following the neoadjuvant chemotherapy; CRT, calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α.

Table III.

Association between CRT, eIF-2a, Ki67 expression and clinicopathological features of advanced endometrial cancer patients after NAC.

| Clinical features | n | post-NAC CRT (−/+) | post-NAC CRT (++-+++) | P-value | post-NAC p-eIF2a (−/+) | post-NAC p-eIF2a (++-+++) | P-value | post-NAC Ki67 (−/+) | post-NAC ki67 (++-+++) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66 | 18 | 48 | 23 | 43 | 42 | 24 | ||||

| NAC | 0.007a | <0.001a | <0.001a | |||||||

| Sense | 40 | 6 | 34 | 7 | 33 | 34 | 6 | |||

| Resistance | 26 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 10 | 8 | 18 | |||

| Histology | 0.287 | 0.362 | 0.027a | |||||||

| Non-endometrioid | 17 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 10 | |||

| Endometrioid | 49 | 12 | 37 | 16 | 33 | 35 | 14 | |||

| Lymphnode metastasis | 0.119 | 0.532 | 0.117 | |||||||

| Positive | 24 | 4 | 20 | 8 | 16 | 18 | 6 | |||

| Negative | 42 | 14 | 28 | 15 | 27 | 24 | 18 | |||

| Differentiation | 0.432 | 0.261 | 0.38 | |||||||

| G1 | 25 | 6 | 19 | 7 | 18 | 17 | 8 | |||

| G2, G3 | 41 | 12 | 29 | 16 | 25 | 25 | 16 | |||

| Muscle invasion | 0.391 | 0.5 | 0.222 | |||||||

| >1/2 | 33 | 8 | 25 | 12 | 21 | 23 | 10 | |||

| ≤1/2 | 33 | 10 | 23 | 11 | 22 | 19 | 14 |

P<0.05. NAC, neoadjuvant chemothereapy; pre-NAC, prior to the neoadjuvant chemotherapy; post-NAC, following the neoadjuvant chemotherapy; CRT, calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α.

Correlation to age, FIGO stage, histology, lymph node metastasis, differentiation, and muscle invasion

Group A: The correlations between CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 protein content and various clinical factors are listed in Table I. There was a significant association between CRT and Ki67 and FIGO stage (PCRT=0.001; Pki67=0.010), histology (PCRT=0.000; Pki67=0.019), and differentiation (PCRT=0.001; Pki67=0.018). No associations were noted between the intense immunostaining for CRT and Ki67 and age, lymph node metastasis, and muscle invasion.

Group B: The correlations between CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 protein content and various clinical factors before NAC are listed in Table II. There was a significant association between CRT and Ki67 and NAC (PCRT=0.000; Pki67=0.019) and histology (PCRT=0.001; Pki67=0.043) pre-NAC. No associations were noted between the intense immunostaining for CRT and Ki67 and differentiation, lymph node metastasis, and muscle invasion. There was no significant association between p-eIF2α and histology, differentiation, NAC, lymph node metastasis, and muscle invasion in the pre-NAC group.

The correlations between CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 protein content and various clinical factors after NAC are listed in Table III. There was a significant association between CRT, p-eIF2α, Ki67 and NAC (PCRT=0.007; Pp-eIF2a=0.000, Pki67=0.000) and histology (Pki67=0.027) post-NAC. No associations were noted between the intense immunostaining for CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 and differentiation, lymph node metastasis, muscle invasion, and histology post-NAC.

Analysis of the correlation between the expressions of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 and therapy outcome in group A

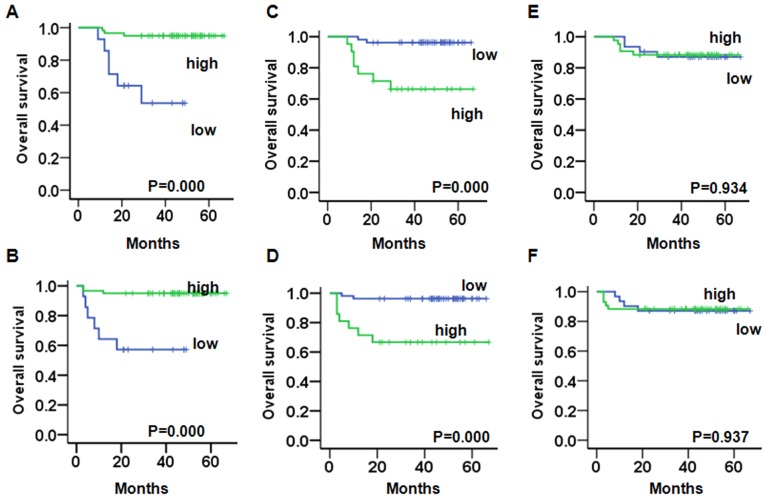

We evaluated the prognostic value of CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 on PFS and OS in endometrioid endometrial cancer and non-endometrioid endometrial cancer patients. A Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that in endometrioid endometrial cancer patients with a weak expression of CRT had a significantly worse OS (PCRT=0.000) (Fig. 2A) and PFS (PCRT=0.000) (Fig. 2B) compared to patients with a strong expression. Patients with a strong expression of Ki67 had a significantly worse OS (Pki67=0.000) (Fig. 2C) and PFS compared to patients with a weak expression (Pki67=0.000) (Fig. 2D). There was no significant change between the weak or strong expression of p-eIF2α and the OS (Fig. 2E) and PFS (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the PFS time and OS time in endometrioid endometrial cancer patients stratified according to CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 expression. (A and B) Kaplan-Meier curves show that patients with a low expression of CRT have a poor OS and PFS. (C and D) Kaplan-Meier curves show that patients with a strong Ki67 expression have a poor OS and PFS. (E and F) Kaplan-Meier curves show that p-eIF2α expression is not significantly associated with OS and PFS. CRT, calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

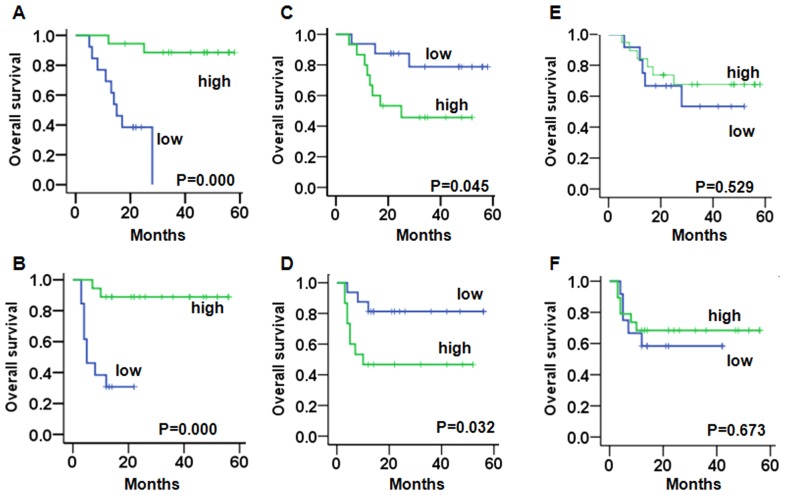

A Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that in non-endometrioid endometrial cancer patients with a weak expression of CRT had a significantly worse OS (PCRT=0.000) (Fig. 3A) and PFS (PCRT=0.000) (Fig. 3B) compared to patients with a strong expression. Patients with a strong expression of Ki67 had a significantly worse OS (Pki67=0.045) (Fig. 3C) and PFS (Pki67=0.032) compared to patients with a weak expression (Fig. 3D). There was no significant change between the weak or strong expression of p-eIF2α and the OS (Fig. 3E) and PFS (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the PFS time and OS time in non-endometrioid endometrial cancer patients stratified according to CRT, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 expression. (A and B) Kaplan-Meier curves show that patients with a low expression of CRT have a poor OS and PFS. (C and D) Kaplan-Meier curves show that patients with a strong Ki67 expression have a poor OS and PFS. (E and F) Kaplan-Meier curves show that p-eIF2α expression is not significantly associated with OS and PFS. CRT, calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Multivariate analysis of prognosis variables in patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer in group A

In the multivariate OS analysis, CRT, p-eIF2α, Ki67, stage, muscle invasion, and lymph node metastases were entered into the Cox regression analysis. CRT expression (hazard ratio (HR), 0.147; P=0.012; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.033–0.661) was an independently significant prognostic factor. Ki67 expression (hazard ratio (HR), 7.559; P=0.020; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.370–41.709) was an independently significant prognostic factor (Table IV). In the multivariate PFS analysis, CRT expression (hazard ratio (HR), 0.164; P=0.018; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.037–0.732) was an independent significant prognostic factor. Ki67 expression (hazard ratio (HR), 7.077; P=0.024; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.293–38.725) was an independently significant prognostic factor (Table IV).

Table IV.

Prognostic factors by multivariate analysis for endometrioid endometrial cancer patients.

| A, PFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Hazard ratio | P-value | 95% CI |

| Lymph node metastases | 0.562 | 0.628 | 0.055–5.785 |

| Positive | |||

| Negative | |||

| Stage | 1.036 | 0.957 | 0.286–3.750 |

| I/II | |||

| III/IV | |||

| Muscle invasion | 0.161 | 0.128 | 0.015–1.695 |

| >1/2 | |||

| ≤1/2 | |||

| CRT | 0.164 | 0.018a | 0.037–0.732 |

| p-eIF-2a | 1.219 | 0.779 | 0.305–4.865 |

| Ki67 | 7.077 | 0.024a | 1.293–38.725 |

| B, OS | |||

| Parameters | Hazard ratio | P-value | 95% CI |

| Lymph node metastases | 0.600 | 0.666 | 0.059–6.118 |

| Positive | |||

| Negative | |||

| Stage | 1.003 | 0.997 | 0.274–3.672 |

| I/II | |||

| III/IV | |||

| Muscle invasion | 0.146 | 0.118 | 0.013–1.634 |

| >1/2 | |||

| ≤1/2 | |||

| CRT | 0.147 | 0.012a | 0.033–0.661 |

| p-eIF-2a | 1.365 | 0.662 | 0.338–5.519 |

| Ki67 | 7.559 | 0.020a | 1.370–41.709 |

P<0.05. CRT, calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Multivariate analysis of prognosis variables in patients with non-endometrioid endometrial cancer in group A

In the multivariate OS analysis, CRT, p-eIF2α, Ki67, stage, muscle invasion, and lymph node metastases were entered into the Cox regression analysis. Stage (hazard ratio (HR), 8.930; P=0.027; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.284–62.111) was an independently significant prognostic factor. Ki67 expression (hazard ratio (HR), 10.011; P=0.013; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.633–61.357) was an independently significant prognostic factor (Table V). In the multivariate PFS analysis, CRT expression (hazard ratio (HR), 0.068; P=0.038; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.005–0.858) was an independent significant prognostic factor. Ki67 expression (hazard ratio (HR), 21.326; P=0.009; 95% confidence interval (CI), 2.120–214.573) was an independently significant prognostic factor (Table V).

Table V.

Prognostic factors by multivariate analysis for non-endometrioid endometrial cancer patients.

| A, PFS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Hazard ratio | P-value | 95% CI |

| Lymph node metastases | 2.624 | 0.302 | 0.420–16.408 |

| Positive | |||

| Negative | |||

| Stage | 3.006 | 0.158 | 0.652–13.868 |

| I/II | |||

| III/IV | |||

| Muscle invasion | 1.002 | 0.998 | 0.264–3.807 |

| >1/2 | |||

| ≤1/2 | |||

| CRT | 0.068 | 0.038a | 0.005–0.858 |

| p-eIF-2a | 1.712 | 0.483 | 0.381–7.703 |

| Ki67 | 21.326 | 0.009a | 2.120–214.573 |

| B, OS | |||

| Parameters | Hazard ratio | P-value | 95% CI |

| Lymph node metastases | 1.640 | 0.602 | 0.256–10.488 |

| Positive | |||

| Negative | |||

| Stage | 8.930 | 0.027a | 1.284–62.111 |

| I/II | |||

| III/IV | |||

| Muscle invasion | 1.043 | 0.953 | 0.251–4.346 |

| >1/2 | |||

| ≤1/2 | |||

| CRT | 0.080 | 0.050 | 0.006–1.005 |

| p-eIF-2a | 1.241 | 0.782 | 0.270–5.697 |

| Ki67 | 10.011 | 0.013a | 1.633–61.357 |

P<0.05. CRT, calreticulin; p-eIF2α, phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

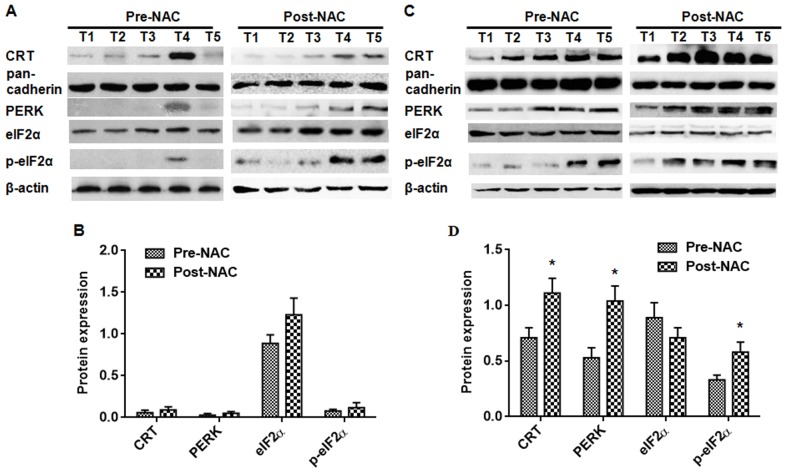

The expression of CRT, PERK, eIF2α, and p-eIF2α in advanced endometrial cancer tissues by western blot

To investigate the potential role of CRT in the tumorigenesis of endometrial cancer, a Western blot was performed on tissue from endometrial cancer patients receiving DOX-NAC. The CRT, PERK, and p-eIF2α protein content was not significantly correlated with pre-NAC and post-NAC in DOX-resistant endometrial cancer (Fig. 4A and B). In the DOX-sensitive endometrial cancer patient tissues, the CRT, PERK, and p-eIF2α protein content was lowly expressed in the pre-NAC group compared with the post-NAC group (Fig. 4C and D) (P<0.05). There was no significant difference on the expression of eIF2α in both the DOX-sensitive group and the DOX-resistant group (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Assessment of CRT, PERK, eIF2α, and p-eIF2α protein content by Western blot analysis. The protein content of CRT, PERK, eIF2α, and p-eIF2α in 12 pairs of DOX-resistant endometrial cancer patients and DOX-sensitive endometrial cancer patients was assessed. In the DOX-resistant endometrial cancer samples, the CRT, PERK, eIF2α, and p-eIF2α protein content was not significantly different between the pre-NAC and post-NAC. (A) In the DOX-sensitive endometrial cancer samples, the CRT, PERK, and p-eIF2α protein content was significantly increased in the post-NAC group compared with the pre-NAC group. (C) There was not a significant change in the eIF2α protein content in the DOX-sensitive endometrial cancer samples. The expression levels were normalized to the actin/pan-cadherin expression values. (B and D) The data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations, which were calculated from three parallel experiments. *P<0.05. CRT; calreticulin; PERK, PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase.

Discussion

CRT has been evaluated as a potential biomarker in several types of cancer, including neuroblastoma (13), bladder (14), gastric (15), breast cancer (16), and acute myeloid leukemia (17). To our knowledge, the expression of CRT is not reported in endometrial cancer, and the prognostic impact of CRT levels has not been studied. Here, we assessed the prognostic value of CRT expression in two independent retrospective cohorts of patients with endometrial cancer. One cohort was treated by primary surgery without DOX-NAC (n=105), and the second cohort was treated with DOX-NAC followed by surgery (n=66). In this retrospective study, we evaluated the expression of CRT, PERK, eIF2α, p-eIF2α, and Ki67 in endometrial cancer and examined the prognostic implications. The overexpression of CRT was associated with the survival of patients with endometrial cancer, and a low expression of CRT was associated with DOX-resistance in endometrial cancer.

In the primary surgery, CRT expression correlated with the FIGO stage, the histology, and the differentiation of endometrial cancer. The Cox multivariate regression analyses confirmed that CRT and Ki67 expression were independent prognostic factors in endometrioid endometrial cancer. High CRT levels were associated with a longer survival both in the endometrioid endometrial cancer group examined. Neuroblastoma is the most common malignancy in infants, and a positive CRT staining was correlated with a better prognosis and a higher patient survival (13). In addition, a stronger CRT expression and a higher infiltration of CD3+ and CD45RO+ cells in colon cancer were associated with a higher 5-year survival rate (18). Kageyama et al observed higher amounts of CRT in the urine samples of patients with bladder cancer and proposed CRT as a biomarker in bladder cancer (14). CRT protein expression is correlated with tumor size and metastatic potential in breast cancer (19), suggesting that CRT levels might only predict patient survival in certain cancer types.

Previous studies demonstrate that the cell surface expression of CRT serves as an ‘eat me’ signal (20) and induces immunogenic tumor cell death (21–23). Activated PERK is a classical precursor for ICD-associated CRT expression. We have demonstrated that in vitro DOX induced the death of tumor cells by ER stress (p-eIF2a, PERK)-mediated CRT expression in EC cells. Induction of ER stress by p-eIF2a in drug-resistant EC cells up-regulated the membrane expression of CRT (in press). The increased expression of ATF6, GRP78, and CHOP/GADD153 in estrogen-related endometrioid carcinomas tissues indicates that ER stress is activated in endometrial cancer (24). PFS and OS are not associated with the expression of PERK, EGFR, the estrogen receptor, and the progesterone receptor in primary and recurrent endometrial cancer (25).

To date, the expression of p-eIF2α in endometrial cancer tissues or cell lines has not been reported. The relationship between the expression of p-eIF2α and OS/PFS in endometrial cancer patients is still unknown. Our data revealed that the expression of p-eIF2α was not associated with the clinicopathological features of endometrial carcinoma patients treated by primary surgery. ER stress induced by realgar quantum dots was confirmed by the increased expression of GADD153 and GRP78 at both the mRNA and protein levels and led to endometrial carcinoma cell apoptosis and necrosis (26). However, whether the ER stress stimulates and processes the ICD-associated CRT expression in endometrial cancer remains to be investigated.

Historically, chemotherapy is thought to induce cancer cell death in an immunogenically silent manner. However, recent studies demonstrate that the therapeutic outcomes with specific chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., anthracyclines) correlate strongly with their ability to induce ICD in cancer cells. After chemotherapy with doxorubin, CRT is translocated from the ER to the cytosol and then, subsequently to the cell surface. Interestingly, when immunocopetent mice were injected with cancer cells and treated ex vivo with anthracyclines recombinant CRT was successfully used as an anti-tumor vaccination (27). Moreover, DOX failed to promote the translocation of CRT and the phagocytosis of the drug-resistant HT29-dx and HT29 iNOS-cells, which resulted in both a chemoresistant and an immunoresistant phenotype (28). In our study, among the patients in group B, there was a significant increase in the expression of CRT in the DOX-sensitive endometrial cancer patients both in pre-NAC and post-NAC by IHC. In addition, the protein expressions of CRT, PERK, and p-eIF2α were significantly increased after DOX-NAC in the DOX-sensitive patient samples. There were no significant difference in the protein expression of CRT, PERK, and p-eIF2α after DOX-NAC in the DOX-resistant patient samples. This suggests that DOX-NAC in advanced endometrial cancer might be associated with a strong constitutive ER stress response that culminates in CRT expression and exposure, facilitating anticancer immunosurveillance.

In conclusion, a high CRT expression, which is likely driven by an ER stress response, constitutes a positive prognostic biomarker in endometrial cancer. CRT expression is associated with the sensitivity of DOX chemotherapy. Low CRT expression in endometrial cancer might represent a new mechanism of immune escape, and monitoring the increasing expression level of CRT on the membrane might indicate new therapeutic strategies for DOX-resistant endometrial cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (81302280) from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (from December 2013 to December 2016).

References

- 1.American Cancer Society, corp-author. Cancer Facts & Figures 2015. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei KR, Chen WQ, Zhang SW, Zheng RS, Wang YN, Liang ZH. Epidemiology of uterine corpus cancer in some cancer registering areas of China from 2003–2007. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2012;47:445–451. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA. Anthropometry, physical activity, and endometrial cancer risk: Results from the Netherlands cohort study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16(Suppl 2):S492. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thigpen JT, Brady MF, Homesley HD, Malfetano J, DuBeshter B, Burger RA, Liao S. Phase III trial of doxorubicin with or without cisplatin in advanced endometrial carcinoma: A gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3902–3908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eggleton P, Bremer E, Dudek E, Michalak M. Calreticulin, a therapeutic target? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2016;20:1137–1147. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2016.1164695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panaretakis T, Kepp O, Brockmeier U, Tesniere A, Bjorklund AC, Chapman DC, Durchschlag M, Joza N, Pierron G, van Endert P, et al. Mechanisms of pre-apoptotic calreticulin exposure in immunogenic cell death. EMBO J. 2009;28:578–590. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garg AD, Krysko DV, Verfaillie T, Kaczmarek A, Ferreira GB, Marysael T, Rubio N, Firczuk M, Mathieu C, Roebroek AJ, et al. A novel pathway combining calreticulin exposure and ATP secretion in immunogenic cancer cell death. EMBO J. 2012;31:1062–1079. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fucikova J, Becht E, Iribarren K, Goc J, Remark R, Damotte D, Alifano M, Devi P, Biton J, Germain C, et al. Calreticulin expression in human non-small cell lung cancers correlates with increased accumulation of antitumor immune cells and favorable prognosis. Cancer Res. 2016;76:1746–1756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du XL, Hu H, Lin DC, Xia SH, Shen XM, Zhang Y, Luo ML, Feng YB, Cai Y, Xu X, et al. Proteomic profiling of proteins dysregulated in Chinese esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007;85:863–875. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaksman O, Davidson B, Tropé C, Reich R. Calreticulin expression is reduced in high-grade ovarian serous carcinoma effusions compared with primary tumors and solid metastases. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2677–2683. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gebremeskel S, Johnston B. Concepts and mechanisms underlying chemotherapy induced immunogenic cell death: Impact on clinical studies and considerations for combined therapies. Oncotarget. 2015;6:41600–41619. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang T, Srivastava S, Hartman M, Buhari SA, Chan CW, Iau P, Khin LW, Wong A, Tan SH, Goh BC, Lee SC. High expression of intratumoral stromal proteins is associated with chemotherapy resistance in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:55155–55168. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu WM, Hsieh FJ, Jeng YM, Kuo ML, Chen CN, Lai DM, Hsieh LJ, Wang BT, Tsao PN, Lee H, et al. Calreticulin expression in neuroblastoma-a novel independent prognostic factor. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:314–321. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kageyama S, Isono T, Matsuda S, Ushio Y, Satomura S, Terai A, Arai Y, Kawakita M, Okada Y, Yoshiki T. Urinary calreticulin in the diagnosis of bladder urothelial carcinoma. Int J Urol. 2009;16:481–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2009.02287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CN, Chang CC, Su TE, Hsu WM, Jeng YM, Ho MC, Hsieh FJ, Lee PH, Kuo ML, Lee H, Chang KJ. Identification of calreticulin as a prognosis marker and angiogenic regulator in human gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:524–533. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0243-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erić A, Juranić Z, Milovanović Z, Marković I, Inić M, Stanojević-Bakić N, Vojinović-Golubović V. Effects of humoral immunity and calreticulin overexpression on postoperative course in breast cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:89–90. doi: 10.1007/s12253-008-9112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wemeau M, Kepp O, Tesnière A, Panaretakis T, Flament C, De Botton S, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G, Chaput N. Calreticulin exposure on malignant blasts predicts a cellular anticancer immune response in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e104. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peng RQ, Chen YB, Ding Y, Zhang R, Zhang X, Yu XJ, Zhou ZW, Zeng YX, Zhang XS. Expression of calreticulin is associated with infiltration of T-cells in stage IIIB colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2428–2434. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i19.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lwin ZM, Guo C, Salim A, Yip GW, Chew FT, Nan J, Thike AA, Tan PH, Bay BH. Clinicopathological significance of calreticulin in breast invasive ductal carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1559–1566. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardai SJ, McPhillips KA, Frasch SC, Janssen WJ, Starefeldt A, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Bratton DL, Oldenborg PA, Michalak M, Henson PM. Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell. 2005;123:321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tongu M, Harashima N, Yamada T, Harada T, Harada M. Immunogenic chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin against established murine carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:769–777. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0797-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez CA, Fu A, Onishko H, Hallahan DE, Geng L. Radiation induces an antitumour immune response to mouse melanoma. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85:1126–1136. doi: 10.3109/09553000903242099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obeid M, Panaretakis T, Joza N, Tufi R, Tesniere A, van Endert P, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Calreticulin exposure is required for the immunogenicity of gamma-irradiation and UVC light-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1848–1850. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bifulco G, Miele C, Di Jeso B, Beguinot F, Nappi C, Di Carlo C, Capuozzo S, Terrazzano G, Insabato L, Ulianich L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is activated in endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leslie KK, Sill MW, Fischer E, Darcy KM, Mannel RS, Tewari KS, Hanjani P, Wilken JA, Baron AT, Godwin AK, et al. A phase II evaluation of gefitinib in the treatment of persistent or recurrent endometrial cancer: A gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:486–494. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Liu Z, Gou Y, Qin Y, Xu Y, Liu J, Wu JZ. Apoptosis and necrosis induced by novel realgar quantum dots in human endometrial cancer cells via endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling pathway. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015;10:5505–5512. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S83838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obeid M, Tesniere A, Ghiringhelli F, Fimia GM, Apetoh L, Perfettini JL, Castedo M, Mignot G, Panaretakis T, Casares N, et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat Med. 2007;13:54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Boo S, Kopecka J, Brusa D, Gazzano E, Matera L, Ghigo D, Bosia A, Riganti C. iNOS activity is necessary for the cytotoxic and immunogenic effects of doxorubicin in human colon cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:108. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]