Abstract

Lung cancer is the most frequently diagnosed neoplasia and represents the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Due to this fact, efforts to improve patient survival through the introduction of novel therapies, as well as preventive actions, are urgently required. Considering this scenario, the antitumoral action of the composite formulation Ocoxin® oral solution (OOS), that contains several antitumoral compounds including antioxidants, was tested in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) in vitro and in vivo preclinical models. OOS exhibited anti-SCLC action that was both time and dose dependent. In vivo OOS decreased the growth of tumors implanted in mice without showing signs of toxicity. The antitumoral effect was due to inhibition of cell proliferation and increased cell death. Genomic and biochemical analyses indicated that OOS augmented p27 and decreased the functioning of several routes involved in cell proliferation. In addition, OOS caused cell death by activation of caspases. Importantly, OOS favored the action of several standard of care drugs used in the SCLC clinic. Our results suggest that OOS has antitumoral action on SCLC, and could be used to supplement the action of drugs commonly used to treat this type of tumor.

Keywords: small cell lung cancer, antioxidants, cell cycle, p27, apoptosis

Introduction

Worldwide, the number of diagnosed lung cancer cases amounts to 1.8 million every year. In fact, globally, this is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths (1). Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for ~15–17% of such lung cancers and is clearly related to cigarette smoking since nearly all SCLC patients were or are active smokers (2). This lung cancer subtype is an aggressive malignancy associated with a poor patient prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate at diagnosis rarely exceeding 15% (3,4). Between 75 and 80% of patients suffer from metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis. For this reason, few patients may benefit from curative surgery (4). On the other hand, in the advanced setting, conventional treatment includes combinations of different chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin, carboplatin, etoposide, irinotecan, topotecan, doxorubicin, adriamycin or cyclophosphamide (4). Nonetheless, a significant clinical challenge is the extremely frequent development of multi-drug resistance, which makes the chemotherapy ineffective after some time.

During the last few years, evidence has accumulated in regards to the increased antitumoral effect of administering conventional chemotherapy in combination with several antioxidants (5,6). Moreover, natural products may be useful anticancer agents. For example, the green tea polyphenol epigallocathechin-3-gallate (EGCG) has been shown in different studies to prevent cancer (7), including lung cancer (8–11). Specifically in regards to SCLC, EGCG has been demonstrated to induce cytotoxicity by the reduction of telomerase activity (12). In addition, DNA fragmentation and apoptosis as well as cell cycle arrest in the S phase were observed. These preclinical in vitro data point to the potential use of EGCG in the treatment of SCLC patients.

Ocoxin® oral solution (OOS) is a nutritional supplement whose formulation includes several compounds with anticancer activity, including EGCG (13), vitamin B6, vitamin C, or cinnamic acid (6,14,15). In addition, OOS contains glycyrrhizinic acid, which exhibits anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects (16). Given such composition, OOS is currently being investigated in clinical trials as part of the treatment of several types of cancer, demonstrating, to date, an improvement in the quality of life of such patients (17,18). Moreover, several recent studies have investigated the potential antitumor effect of OOS on different tumor models, including HER2-positive breast cancer (13), acute myeloid leukemia (19) and hepatocellular carcinoma (20). In all these models, OOS exhibited clear antitumor properties both in vitro and in vivo in xenograft mouse models. At the mechanistic level, OOS seemed to induce a general delay of cell cycle progression. In fact, in breast cancer as well as in AML models, cell cycle blockage seems to be mediated by the increase in the cell cycle inhibitor p27 (13,19).

Based on these precedents, the effects of OOS on preclinical models of SCLC were explored. The potential antiproliferative action of this formulation was initially assessed in vitro using two different SCLC cell lines alone and in combination with other conventional antitumoral drugs. Its in vivo action was analyzed using a xenograft model that showed a reduction in tumor growth in animals that received OOS. Finally, the mechanisms responsible for such decrease were examined both in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Cell culture media, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics were from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Immobilon P (PVDF) membranes from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA). OOS was provided by Catalysis, S.L. (Madrid, Spain). Its formulation included per 50 ml of solution: L-glycine 1,000 mg, glucosamine sulfate 1,000 mg, L-arginine 320 mg, L-cysteine 102 mg, licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) 100 mg, vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid) 60 mg, water, zinc sulfate 40 mg, green tea extract (Camellia sinensis L. Kuntze) 12.5 mg, vitamin B5 (D-calcium pantothenate) 6 mg, vitamin B6 (pyridoxine hydrochloride) 2 mg, manganese sulfate 2 mg, cinnamon extract (Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume) 1.5 mg, folic acid (pteroylmonoglutamic acid) 200 μg, vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin) 1 μg, acidulant (malic acid) and preservative (sodium methylparaben). Other generic chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Roche Biochemicals (Basel, Switzerland) or Merck (Darmstadt, Germany).

The origins of the different antibodies used in the western blot analyses were as follows: the anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (sc-166574, mouse monoclonal, used at 1:10,000) and the anti-PARP (sc-8007, mouse monoclonal, 1:5,000) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA); the anti-Rb (#554136, mouse monoclonal, 1:1,000) and anti-caspase-3 (#610323, rabbit polyclonal, 1:5,000) from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and the anti-p27 (#3686, rabbit polyclonal, 1:5,000), anti-caspase-8 (#9746, mouse monoclonal, 1:1,000), anti-caspase-9 (#9502, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000), anti-caspase-7 (#9492, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (#9664, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000) and anti-bid (#2002, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1,000) from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit, 170-6515, 1:20,000 and goat anti-mouse 170-6516, 1:10,000) were from Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. (Hercules, CA, USA).

Cell culture, protein extraction and western blotting (WB)

SCLC cell lines were grown in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere in the presence of 5% CO2-95% air. The two SCLC cell lines used in this study have already been described (21–23) and were generously provided by Dr Clementi (CNR Center of Cytopharmacology, Milan, Italy). Furthermore, GLC-8 cells were initially isolated from a tumor biopsy of an SCLC (22), while DMS 92 cells came from a bone marrow metastasis of an SCLC (21).

To prepare for protein purification, cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (24). Protein quantification, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and WB analysis were performed as previously described (24).

Cell cycle and BrDU incorporation assay

For cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry, ethanol-fixed cells were stained with 5 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) and 250 μg DNase-free RNAse. A total of 50,000 cells were acquired in the PI gate by using a BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer and the C6 (version 1.0.264.21) software (BD Biosciences).

To measure bromodeoxyuridine (BrDU) incorporation, the Cell Proliferation ELISA, BrdU (colorimetric) kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was used following the manufacturer's instructions. Data were acquired using a BioTek Synergy 4 reader with Gen5 1.05 software (both from BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Assessment of cell death and cell proliferation

For analysis of apoptotic cell death, GLC-8 cells were treated for 48 h with OOS diluted 1:25 in culture media or left untreated (control), resuspended in binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 nM CaCl2, pH 7.4) containing 5 μl Annexin V-FITC (BD Biosciences) and 5 μl 50 μg/ml PI, and stained at room temperature for 15 min. A total of 50,000 cells were acquired using the BD Accuri™ C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) as previously described.

Cell proliferation of SCLC cells was examined using a modified MTT metabolization assay (19). At least three wells were analyzed for each condition, and the results are presented as the mean ± SD of a representative experiment repeated at least twice.

In vivo experiments

For the animal studies, 12 7-week-old female athymic mice (CB17-SCID) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) and maintained in pathogen-free housing at our Institutional Animal Care Facility. Animal experiments were performed according to the institutional guidelines and protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of CSIC-Universidad de Salamanca (Salamanca, Spain). One week later, 6×106 GLC-8 cells resuspended in 50 μl of RPMI-1640 and 50 μl of Matrigel were subcutaneously injected into the right caudal flank of each animal. When tumors became palpable, mice were randomized into two groups (n=6 per group), that were administered vehicle alone (control group) or 100 μl OOS per mouse (20 g). Treatments were administered for 31 days with a daily schedule (Monday to Friday) by oral gavage. Mice were weighed and tumors measured twice a week with a digital caliper (Proinsa, Vitoria, Spain). Tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula: V = (L/2) × (W/2)2 × 4/3 × π, where V, volume (cubic mm); L, length (mm); and W, width (mm). At the time of sacrifice, tumor tissue was resected and part of the tumor was immediately frozen at −80°C. Another part was fixed in formalin for further analyses.

Histological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses

Representative tumor areas were fixed in formalin, paraffin-embedded, cut in 2- to 3-μm sections, and either stained with H&E or prepared for IHC, that was performed as previously described (19). Thus, two cell conditioning periods of 8 min at 95°C and 4 min at 100°C on a hot plate using Tris-EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer were performed on previously dewaxed formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections. Sections were then incubated with the a 1:50 dilution of an anti-Ki-67 antibody (clon SP6; Master Diagnóstica, Granada, Spain) and the staining was performed with the IHC 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA). For TUNEL staining, the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was used, and counterstained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole. Results were evaluated in a manner blinded to the clinicopathological and molecular data. The number and intensity of immunoreactive cells were evaluated in at least 10 randomly selected fields. These procedures were conducted by independent personnel of the pathology unit of our center. Conflict measurements were solved by consensus.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and microarray hybridization and analysis

After thawing, tumors were excised and lysed in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, tumors were homogenized (Dispomix; L&M Biotech, Holly Springs, NC, USA) and incubated in TRIzol solution for 2 min at room temperature, before the addition of chloroform. Tubes were vigorously shaken and the different phases were separated by centrifugation at 18,000 × g and 4°C for 15 min. The upper, aqueous phase was recovered and the RNA present was precipitated with isopropyl alcohol. Once washed in 70% ethanol, the resultant RNA was column-purified (RNeasy Mini kit; Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA) and its integrity was assessed (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Biotinylated complementary RNA was then synthesized (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA) and hybridized to human Clarion™ S GeneChip oligonucleotide arrays (Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Quantitation of fluorescence intensities of probesets was conducted using the GenArray Scanner (Hewlett Packard). Unprocessed files were normalized using the RMA algorithm implemented in the Affymetrix Expression Console (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Differentially expressed genes were identified using significant analysis of microarrays, selecting all genes with a value of Q≤0.05.

Statistical analysis

Each condition was analyzed in triplicate or quadruplicate and data are presented as the mean ± SD of an experiment that was repeated at least three times. Comparisons of continuous variables between two groups were performed using two-sided Student's t-test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant when P-values were <0.05.

Results

Effect of OOS on the proliferation of SCLC cell lines

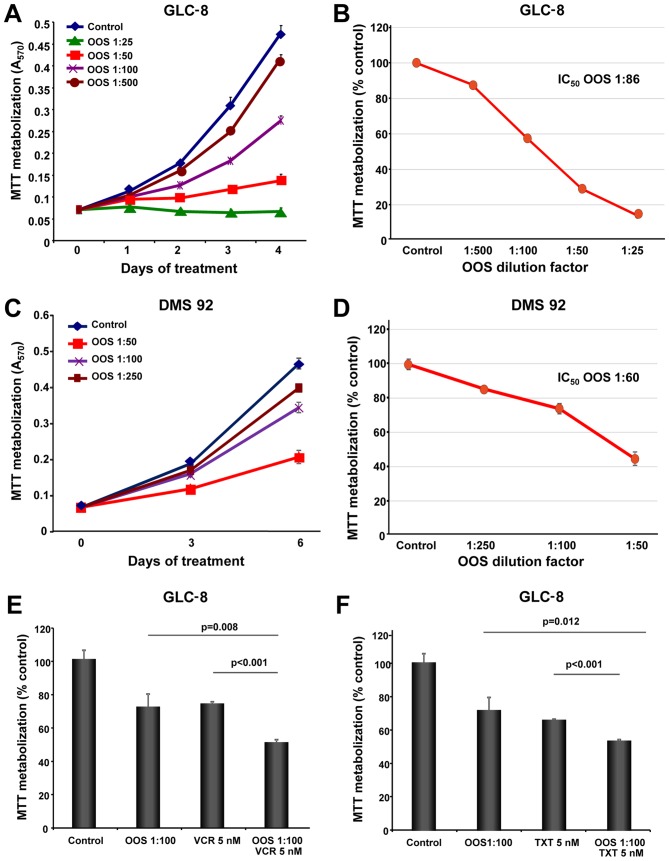

The in vitro action of OOS was evaluated in the SCLC cell lines GLC-8 and DMS 92. With this purpose, cells were grown in the presence of increasing doses of OOS diluted in the culture medium and their proliferation was evaluated using MTT metabolization assays performed at different days of treatment. OOS decreased MTT metabolization in these cells in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A and C). The IC50 values determined for GLC-8 cells after 4 days and DMS 92 cells after 6 days of treatment were a 1:86 dilution and a 1:60 dilution, respectively (Fig. 1B and D).

Figure 1.

Efficacy of OOS on SCLC cells in vitro. (A) Dose-dependent effect of OOS on the proliferation of GLC-8 cells was assessed in vitro. Cells were incubated with OOS at the indicated dilution factors and MTT metabolization was measured as indicated. (B) Calculation of the IC50 of OOS. Mean absorbance values of the untreated samples were considered as 100% and the mean values were referred to the control value. (C and D) Similarly, dose-dependent effect of OOS on DMS 92 cells was determined (C) and the IC50 value was calculated (D). (E and F) The effect of OOS alone (1:100) or in combination with vincristine [VCR 5 nM (E)] or docetaxel [TXT 5 nM (F)] were determined by MTT assays. The mean absorbance values of the untreated samples were considered as 100%. Data are represented as mean ± SD of quadruplicates of an experiment that was repeated at least twice. OOS, Ocoxin® oral solution; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration.

Effect of OOS in combination with standard of care SCLC treatments

In most of the cases, the success of antitumor therapies is based on the combination of different agents. For this reason, we aimed to ascertain whether the combination of OOS with drugs commonly used in the SCLC clinic could improve their antitumor effect. Thus, GLC-8 cells were treated for 2 days with OOS alone (diluted 1:100 in regular media), or in combination with vincristine (VCR, 5 nM), docetaxel (TXT, 5 nM) or cisplatin (2 or 20 μM). The combination of OOS with this latter compound did not exhibit a superior antiproliferative effect to the one observed for each of the individual treatments (data not shown). In the case of VCR or TXT, the combinations were more effective for inhibiting MTT metabolization than the independent treatment with any of the agents (Fig. 1E and F). In fact, when the combination index (CI) of OOS and VCR was calculated using Calcusyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) an additive effect of both drugs was demonstrated (CI between 0.9 and 0.96, data not shown).

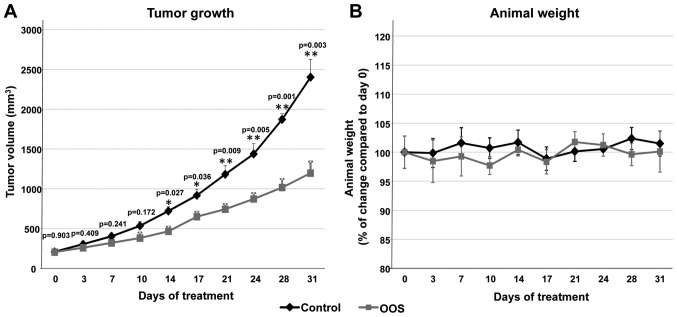

In vivo efficacy of OOS in SCLC murine models

Given the antitumoral action of OOS in vitro, we explored whether this effect could also be observed in vivo. With this aim, we used a xenograft murine model to determine the effect of OOS treatment once the tumors were already established. CB17-SCID athymic mice were injected with GLC-8 cells and when tumors were palpable and had correctly been engrafted and started to grow, the animals were randomized into two different groups that were orally treated with water (control) or 100 μl OOS per 20 g of animal weight (OOS). Initially, tumors included in the two groups had a similar volume (209.3±17.2 vs. 206.1±16 mm3, mean ± SEM, respectively). Tumoral sizes were measured twice a week for a total time period of 31 days. After 14 days of oral treatment with OOS, a significant decrease in the growth of the tumors was observed (p=0.027) (Fig. 2A). Nonetheless, such differences increased along the time of treatment. Thus, at the end of the experiment, the mean tumor volume of the control mice was 2,402.6±223.6 mm3, as compared with 1,197±144.4 mm3 for the group treated with OOS (p=0.003) (Fig. 2A). The mean body weight of the control or treated mice did not substantially change throughout the duration of the experiment (Fig. 2B), indicative of good tolerability to OOS in our experimental conditions.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of OOS on SCLC models in vivo. (A) OOS interferes with tumor growth. Female CB17-SCID athymic mice were injected with 6×106 GLC-8 cells. When tumors became palpable and maintained growth, they were randomized to different groups and were orally treated 5 days per week (Monday to Friday) with 100 μl OOS/animal or vehicle alone (water), and tumor volumes were measured twice a week. Data are represented as mean tumor volume ± SEM of the animals in each group. (B) Effect of OOS on animal weight. Statistical significant differences are shown (*p<0.05). OOS, Ocoxin® oral solution; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

Mechanism of action of OOS on SCLC cells

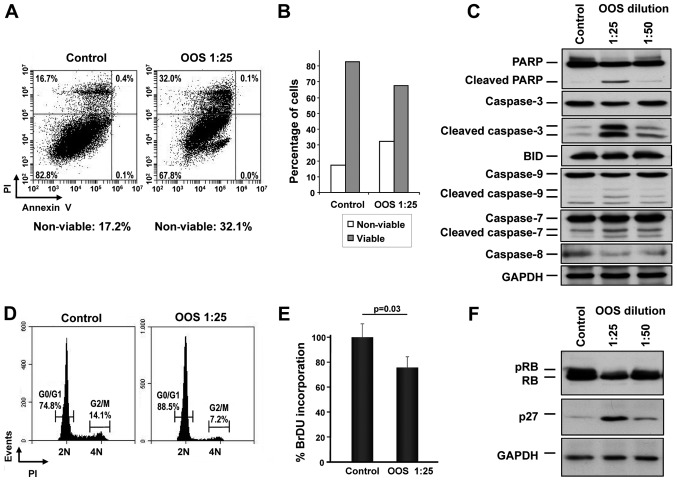

The mechanisms leading to the in vitro reduction of MTT metabolization were next analyzed. We proposed that such a reduction could be due to an increase in cell death, reduced cell cycle progression or a combination of both. Thus, the capability of OOS to induce apoptotic cell death was assessed. GLC-8 cells were treated for 24 h with OOS diluted at 1:25 in culture medium and apoptotic cell death was determined by double staining with Annexin V and PI. A slight increase in the percentage of cells stained by both Annexin V and PI was observed after OOS treatment (control, 16.7% vs. OOS-treated, 32.0%) (Fig. 3A). Analysis of the total viable vs. non-viable population confirmed the induction of cell death by OOS (Fig. 3B). Moreover, when the levels of the cleavage of several proteins involved in apoptosis such as PARP or different caspases were determined by western blotting, a clear induction of their proteolytic processing indicative of activation was detected, especially at dilutions of OOS of 1:25 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

OOS induces cell death as well as cell cycle retardation in vitro. (A) GLC-8 cells were treated for 24 h with OOS (1:25), harvested and stained with Annexin V and PI to determine apoptotic cell death. (B) Representation of the viable and non-viable populations of the experiment shown in (A). (C) Quantification of the levels of apoptosis-related proteins after OOS treatment. GLC-8 cells were treated with OOS as in (A) and the levels of the indicated proteins were analyzed by conventional WB. (D) Cell cycle profile of the OOS-treated cells. GLC-8 cells were treated as in (A), harvested, fixed and the DNA content of the living cells was determined by PI staining. (E) OOS treatment caused a decrease in the percentage of cells in the S phase. To measure that population, GLC-8 cells were treated for 24 h with OOS at 1:25 and then incubated in the presence of BrDU for another 3 h. BrDU incorporation was measured using a colorimetric assay as described and normalized to that of the untreated controls. (F) Action of OOS on p27 and retinoblastoma protein (RB) protein levels. GLC-8 cells were treated for 24 h with OOS (1:25 and 1:50 dilution) and cell extracts were prepared to analyze p27 and RB by WB. GAPDH was used as a loading control. OOS, Ocoxin® oral solution; WB, western blotting; PI, propidium iodide.

We next investigated whether OOS could induce changes in cell cycle progression. Cells were treated with OOS and cytometrically analyzed after PI staining of the DNA. In those conditions, treatment with OOS resulted in an increase in the G0/G1 population, increasing from 74.8 to 88.5%. Consequently, there was a concomitant decrease in the percentage of cells in the G2/M (from 14.1 to 7.2%) or S phases (from 11.1 to 4.3%) following treatment with OOS (Fig. 3D). The capability of OOS to interfere with DNA synthesis was evaluated using an alternative technique that allows the quantification of cells progressing through S phase by the measure of its BrDU incorporation. With this assay, a reduction in the S phase population was demonstrated (Fig. 3E), pointing to a slowdown in cell cycle progression as part of the mechanism of action of OOS.

The cell cycle effects of OOS in other cellular models seems to be mediated by an increase in the cell cycle inhibitory protein p27 (13,19). To explore whether such a mechanism of action could as well participate in the effect of OOS on SCLC cells, p27 protein levels were determined by western blotting both in control untreated cells or after 24 h of treatment with 1:25 or 1:50 dilutions of OOS. When a dilution factor of 1:25 was used, a clear increase in the p27 level was observed (Fig. 3F). Moreover, this increase was correlated with a decrease in the phosphorylation and total levels of the retinoblastoma protein (pRB and RB, respectively) (Fig. 3F).

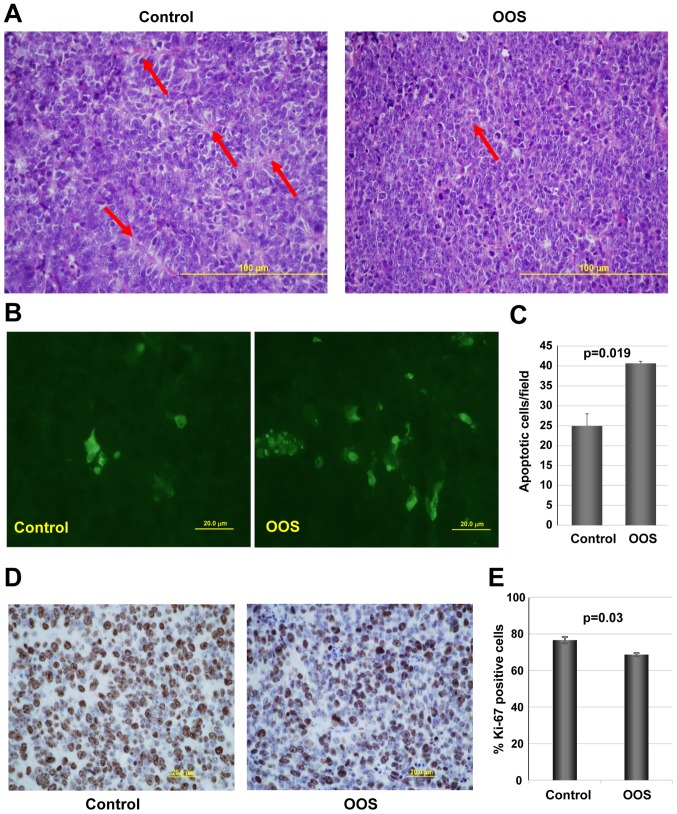

Effect of OOS on cell proliferation and apoptosis in vivo

We next investigated the potential mechanisms leading to the decrease in tumor growth observed in OOS-treated animals, when compared to the untreated controls. We first evaluated the general tumor aspects after H&E staining. Independently of whether the animal received treatment of not, the tumoral masses dissected from the animals presented a large central apoptotic/necrotic area that extended to up to 60% of the tumor (data not shown). Tumor cells were in general poorly differentiated, with a high mitotic index. Additionally, control tumors seemed to be better vascularized than OOS-treated ones. In fact, control tumors seemed to be more pseudo-glandular than the treated ones (arrows in Fig. 4A). In line with this, tumors from animals which received OOS exhibited a more compact aspect (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

OOS induces an increase in cell death and a decrease in proliferation in vivo. At the time of sacrifice, part of the tumors from animals shown in Fig. 2 were fixed and included in paraffin for further analysis. (A) H&E staining of control (left panel) or OOS-treated (right panel) tumors. (B) OOS treatment causes an increase in intratumoral apoptotic cell death. For each experimental condition, two tumors were randomly processed for IHC analysis and apoptotic cells were detected by TUNEL staining. Images of representative fields stained for this marker are shown. (C) The number of apoptotic cells per field was quantified for each condition and its mean number ± SD is shown in the graph. (D) To establish the proliferative status of the tumors, Ki-67 marker was used and images of representative fields stained for Ki-67 are presented. (E) Quantification of the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells from (D). Statistical significant differences are shown (p<0.05). OOS, Ocoxin® oral solution.

We next evaluated the level of apoptotic cells in the control and OOS-treated animals. While, as mentioned above, when observed under a microscope the central apoptotic/necrotic area observed was similar in both experimental conditions, in OOS-treated tumors more apoptotic regions within non-necrotic tissue could be observed. Analysis of apoptotic cell death after TUNEL staining technique showed that tumors from the OOS-treated animals contained a larger number of apoptotic cells than tumors from untreated animals (Fig. 4B). Moreover, quantitative analyses of the TUNEL-stained tumors corroborated that the number of apoptotic cells detected per field was significantly lower in the control condition than that in the treated tumors (p=0.019) (Fig. 4C). Together, these data demonstrate that OOS triggers the apoptotic cell death of SCLC cells in the in vivo setting.

The expression of human Ki-67, a protein associated with cell proliferation, was also evaluated. Treatment with OOS induced a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of Ki-67-positive cells (Fig. 4D and E). The decrease in Ki-67 levels was indicative of a reduced proliferation of OOS-treated tumors.

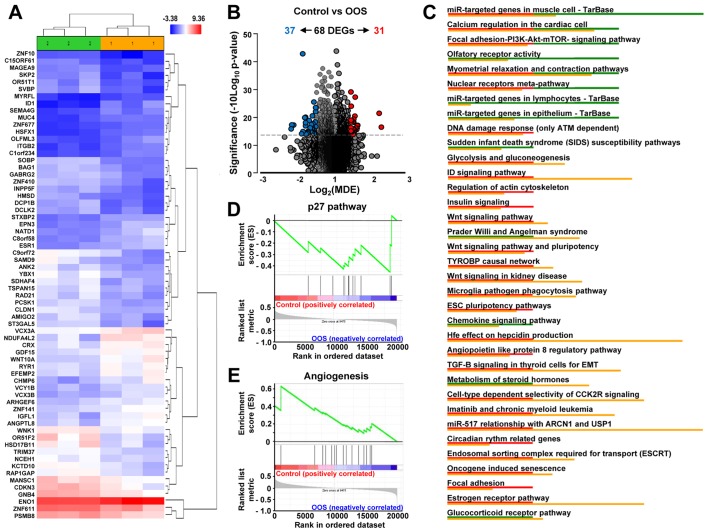

Transcriptional effect of OOS in vivo

To gain further insight into the molecular mechanism leading to the in vivo reduction in tumor growth, we investigated the changes in gene expression profiles induced by OOS treatment. Unsupervised clustering of the gene expression data clearly associated samples into two groups, control and OOS-treated, indicating that treatment with OOS was able to change the transcriptome to make treated samples to diverge from the untreated control tumors (Fig. 5A). Quantitative comparison of both conditions defined 68 deregulated genes (fold change of at least ±1.5) (Table I). Volcano plots indicated that among them, 31 genes were upregulated in the control condition whereas 37 were increased after OOS treatment (Fig. 5B). Among the deregulated genes, NADH dehydrogenase NDUFA4L2 (2.26-fold higher expression), the ID1 inhibitor of DNA binding (2.2-fold) or ITGB2 (1.7-fold) had a higher expression in the control samples than in those from animals treated with OOS. In contrast, the opposite situation was the olfactory receptor OR51F2 (2.17-fold higher expression in OOS-treated samples) or YBX1 acceptor (2.12-fold), among others (Table I). Additionally, several intracellular pathways were deregulated, including the DNA damage response pathways, cell cycle regulation, or the PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Wnt or insulin signaling, all of them involved in cell proliferation/apoptosis (Fig. 5C). Moreover, when the GSEA software was used to analyze these gene-expression data, the p27 pathway (Fig. 5D) and certain pro-apoptotic pathways (data not shown) were found to be upregulated in the OOS-treated tumors. In addition, several angiogenesis-related datasets were downregulated in tumors derived from OOS-treated animals, as shown in Fig. 5E.

Figure 5.

In vivo effect of OOS on gene expression profiles. (A) Hierarchical clustering of the 6 tumors and the 68 genes deregulated after OOS treatment. Each row represents a gene and each column represents a tumor (1, control; 2, OOS-treated). The expression level of each gene in each tumor is relative to its medium abundance across all the tumors and is depicted according to the color scale shown. Red and blue indicate high or low expression levels, respectively. (B) Volcano plot representation of the deregulated genes found in the gene expression profiles. Blue plots represent the 37 genes upregulated in the control condition while red plots represent the 31 ones upregulated in the treated tumors. (C) Pathways in vivo deregulated after OOS treatment. Genes found to be deregulated at least 1.5-fold in the Affymetrix Expression Console were analyzed with the same software to evaluate the pathways in which gene expression is altered, and those pathways with a higher number of deregulated genes are shown in the figure. Below each altered pathway, genes upregulated in the control condition (red) or after OOS treatment (green) are shown. Upregulation of the p27 pathway (D) and downregulation of angiogenesis-related genes (E) upon GSEA analysis. OOS, Ocoxin® oral solution.

Table I.

In vivo effect of OOS on gene expression profiles.

| Transcript cluster ID | Control Avg signal | OOS Avg signal | Fold change (C vs. OOS) | ANOVA p-value (C vs. OOS) | FDR p-value (C vs. OOS) | Gene symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC1200010961.hg.1 | 6.89 | 5.71 | 2.26 | 0.026035 | 0.698253 | NDUFA4L2 | NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 α subcomplex, 4-like 2 |

| TC2000007083.hg.1 | 4.89 | 3.75 | 2.2 | 0.00829 | 0.698253 | ID1 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 1, dominant negative helix-loop-helix protein |

| TC2100007394.hg.1 | 4.84 | 4.07 | 1.7 | 0.022428 | 0.698253 | ITGB2 | Memczak2013 ANTISENSE, CDS, coding, INTERNAL best transcript NM_001127491 |

| TC1000008663.hg.1 | 4.99 | 4.24 | 1.69 | 0.023254 | 0.698253 | SEMA4G | Sema domain (Dom), Ig Dom, transmembrane Dom and short cytoplasmic Dom; semaphorin 4G |

| TC1700012281.hg.1 | 5.62 | 4.88 | 1.68 | 0.028637 | 0.698253 | EPN3 | Epsin 3 |

| TC0200011898.hg.1 | 7.56 | 6.82 | 1.67 | 0.032135 | 0.698253 | SDC1 | Syndecan 1 |

| TC0100013266.hg.1 | 4.94 | 4.22 | 1.64 | 0.02815 | 0.698253 | C1orf234 | Chromosome 1 open reading frame 234 |

| TC0X00008694.hg.1 | 4.67 | 3.97 | 1.63 | 0.002167 | 0.698253 | HSFX1 | Heat shock transcription factor family, X-linked 1 |

| TC0300013665.hg.1 | 4.72 | 4.03 | 1.62 | 0.010431 | 0.698253 | MUC4 | Mucin 4, cell surface associated |

| TC0X00006567.hg.1 | 6 | 5.3 | 1.62 | 0.03384 | 0.698253 | VCX3B; VCX | Variable charge, X-linked 3B; variable charge, X-linked |

| TC0400006449.hg.1 | 6.39 | 5.7 | 1.61 | 0.033002 | 0.698253 | ZNF141 | Transcript Identified by AceView, Entrez Gene ID(s) 100288237; 7700 |

| TC0Y00007078.hg.1 | 5.99 | 5.31 | 1.6 | 0.038427 | 0.698253 | VCY; VCY1B | Variable charge, Y-linked; variable charge, Y-linked 1B |

| TC1700010088.hg.1 | 5.62 | 4.94 | 1.6 | 0.0348 | 0.698253 | NATD1 | N-acetyltransferase domain containing 1 |

| TC0100006755.hg.1 | 9.2 | 8.54 | 1.59 | 0.013559 | 0.698253 | ENO1 | Memczak2013 ANTISENSE, coding, INTERNAL, UTR3 best transcript NM_001428 |

| TC0100018271.hg.1 | 4.91 | 4.24 | 1.59 | 0.045745 | 0.698253 | OLFML3 | Olfactomedin like 3 |

| TC0X00006558.hg.1 | 6.93 | 6.26 | 1.59 | 0.017512 | 0.698253 | VCX; VCX3A | Variable charge, X-linked; variable charge, X-linked 3A |

| TC1100011257.hg.1 | 6.5 | 5.83 | 1.59 | 0.030276 | 0.698253 | EFEMP2 | EGF containing fibulin-like extracellular matrix protein 2 |

| TC1700009144.hg.1 | 6.03 | 5.37 | 1.58 | 0.043374 | 0.698253 | CHMP6 | Charged multivesicular body protein 6 |

| TC1200012664.hg.1 | 4.37 | 3.72 | 1.57 | 0.047618 | 0.698253 | MYRFL | Myelin regulatory factor-like |

| TC1900011334.hg.1 | 4.7 | 4.04 | 1.57 | 0.016798 | 0.698253 | ZNF677 | Zinc finger protein 677 |

| TC0600009871.hg.1 | 5.52 | 4.88 | 1.56 | 0.029687 | 0.698253 | ESR1 | Estrogen receptor 1 |

| TC1900008366.hg.1 | 6.17 | 5.55 | 1.54 | 0.038319 | 0.698253 | IGFL1 | IGF like family member 1 |

| TC1900011772.hg.1 | 6.53 | 5.91 | 1.54 | 0.015269 | 0.698253 | CRX | Cone-rod homeobox |

| TC0200010818.hg.1 | 6.34 | 5.73 | 1.53 | 0.016051 | 0.698253 | WNT10A | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 10A |

| TC0800012281.hg.1 | 5.44 | 4.84 | 1.52 | 0.004602 | 0.698253 | C8orf58 | Chromosome 8 open reading frame 58 |

| TC1900008017.hg.1 | 6.5 | 5.89 | 1.52 | 0.03701 | 0.698253 | RYR1 | Ryanodine receptor 1 (skeletal) |

| TC0100012921.hg.1 | 7.49 | 6.9 | 1.51 | 0.027124 | 0.698253 | DHRS3; MIR6730 | Dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR family) member 3; microRNA 6730 |

| TC0X00010933.hg.1 | 6.1 | 5.51 | 1.51 | 0.017036 | 0.698253 | ARHGEF6 | Rac/Cdc42 guanine nucleotide exchange factor 6 |

| TC1900007020.hg.1 | 6.28 | 5.68 | 1.51 | 0.03582 | 0.698253 | ANGPTL8 | Angiopoietin like 8 |

| TC1900007384.hg.1 | 6.52 | 5.93 | 1.51 | 0.014667 | 0.698253 | GDF15 | Growth differentiation factor 15 |

| TC1900011656.hg.1 | 5.27 | 4.67 | 1.51 | 0.001409 | 0.698253 | STXBP2 | Syntaxin binding protein 2 |

| TC0300013151.hg.1 | 5.75 | 6.34 | −1.51 | 0.024943 | 0.698253 | NCEH1 | Neutral cholesterol ester hydrolase 1 |

| TC0300013264.hg.1 | 6.75 | 7.34 | −1.51 | 0.007192 | 0.698253 | GNB4 | Guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), β polypeptide 4 |

| TC1000007895.hg.1 | 5.36 | 5.96 | −1.51 | 0.047298 | 0.698253 | TSPAN15 | Tetraspanin 15 |

| TC1700011277.hg.1 | 5.68 | 6.27 | −1.51 | 0.005171 | 0.698253 | TRIM37 | Transcript Identified by AceView, Entrez Gene ID(s) 4591 |

| TC1200006454.hg.1 | 6.08 | 6.69 | −1.52 | 0.017021 | 0.698253 | WNK1 | Transcript Identified by AceView, Entrez Gene ID(s) 378465; 65125 |

| TC0600011507.hg.1 | 6.91 | 7.54 | −1.55 | 0.034697 | 0.698253 | PSMB8 | Proteasome subunit β8 |

| TSUnmapped00000243.hg.1 | 6.34 | 6.97 | −1.55 | 0.041704 | 0.698253 | MANSC1 | MANSC domain containing 1 |

| TC0100013902.hg.1 | 4.58 | 5.22 | −1.56 | 0.039592 | 0.698253 | SVBP | Small vasohibin binding protein |

| TC0500011513.hg.1 | 5.24 | 5.88 | −1.56 | 0.003247 | 0.698253 | PCSK1 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 1 |

| TC1900011312.hg.1 | 7.48 | 8.12 | −1.56 | 0.044255 | 0.698253 | ZNF611 | Zinc finger protein 611 |

| TC0300013520.hg.1 | 5.41 | 6.08 | −1.59 | 0.019529 | 0.698253 | CLDN1 | Claudin 1 |

| TC0100013223.hg.1 | 5.83 | 6.51 | −1.6 | 0.027675 | 0.698253 | RAP1GAP | RAP1 GTPase activating protein |

| TC0X00011080.hg.1 | 4.29 | 4.97 | −1.6 | 0.010211 | 0.698253 | MAGEA9; MAGEA9B | MAGE family member A9; MAGE family member A9B |

| TC0800011566.hg.1 | 5.2 | 5.89 | −1.61 | 0.041099 | 0.698253 | RAD21 | Transcript Identified by AceView, Entrez Gene ID(s) 5885 |

| TC1200011870.hg.1 | 5.78 | 6.47 | −1.61 | 0.030776 | 0.698253 | KCTD10 | Potassium channel tetramerization domain containing 10 |

| TC0500007145.hg.1 | 4.22 | 4.92 | −1.62 | 0.049614 | 0.698253 | SKP2 | Transcript Identified by AceView, Entrez Gene ID(s) 6502 |

| TC1200012736.hg.1 | 3.76 | 4.46 | −1.63 | 0.020998 | 0.698253 | ZNF10 | Zinc finger protein 10 |

| TC0400008450.hg.1 | 5.23 | 5.94 | −1.64 | 0.035161 | 0.698253 | ANK2 | Ankyrin 2, neuronal |

| TC1100006674.hg.1 | 4.4 | 5.13 | −1.65 | 0.037934 | 0.698253 | OR51T1 | Olfactory receptor, family 51, subfamily T, member 1 |

| TC1000009092.hg.1 | 4.64 | 5.38 | −1.66 | 0.028207 | 0.698253 | INPP5F | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase F |

| TC1800009244.hg.1 | 4.68 | 5.41 | −1.66 | 0.027752 | 0.698253 | HMSD | Histocompatibility (minor) serpin domain containing |

| TC0900009855.hg.1 | 4.81 | 5.56 | −1.69 | 0.015155 | 0.698253 | BAG1 | Bcl-2-associated athanogene |

| TC0500009304.hg.1 | 4.84 | 5.62 | −1.71 | 0.04978 | 0.698253 | GABRG2 | γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) A receptor, γ 2 |

| TC1200010538.hg.1 | 5.22 | 6 | −1.72 | 0.037044 | 0.698253 | AMIGO2 | Adhesion molecule with Ig-like domain 2 |

| TC1400010625.hg.1 | 4.83 | 5.61 | −1.72 | 0.040343 | 0.698253 | ZNF410 | Zinc finger protein 410 |

| TC0400008972.hg.1 | 4.53 | 5.33 | −1.74 | 0.04379 | 0.698253 | DCLK2 | Doublecortin-like kinase 2 |

| TC0200013298.hg.1 | 5.03 | 5.86 | −1.78 | 0.045777 | 0.698253 | ST3GAL5 | ST3 β-galactoside α-2.3-sialyltransferase 5 |

| TC1200009590.hg.1 | 4.5 | 5.34 | −1.79 | 0.011405 | 0.698253 | DCP1B | Decapping mRNA 1B |

| TC1400007201.hg.1 | 6.39 | 7.23 | −1.79 | 0.02332 | 0.698253 | CDKN3 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 3 |

| TC1500007644.hg.1 | 4.13 | 4.98 | −1.79 | 0.018087 | 0.698253 | C15orf61 | Chromosome 15 open reading frame 61 |

| TC0600008471.hg.1 | 5.3 | 6.16 | −1.81 | 0.011906 | 0.698253 | SDHAF4 | Succinate dehydrogenase complex assembly factor 4 |

| TC0700011796.hg.1 | 5.17 | 6.06 | −1.86 | 0.037538 | 0.698253 | SAMD9 | Sterile α motif domain containing 9 |

| TC0600009019.hg.1 | 4.77 | 5.68 | −1.87 | 0.00006 | 0.429919 | SOBP | Sine oculis binding protein homolog |

| TC0400012945.hg.1 | 5.78 | 6.7 | −1.9 | 0.045226 | 0.698253 | HSD17B11 | Hydroxysteroid (17-β) dehydrogenase 11 |

| TC0100008026.hg.1 | 5.32 | 6.4 | −2.12 | 0.021804 | 0.698253 | YBX1 | Zhang2013 ALT_ACCEPTOR, ALT_DONOR, coding, INTERNAL, intronic best transcript |

| TC1100006671.hg.1 | 5.76 | 6.88 | −2.17 | 0.021524 | 0.698253 | OR51F2 | Olfactory receptor, family 51, subfamily F, member 2 |

| TC0900009779.hg.1 | 5.16 | 6.3 | −2.19 | 0.030103 | 0.698253 | C9orf72 | Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 |

Comparison of the gene expression profiles of three control tumors to that of three OOS treated ones. Table shows those genes whose expression changed >1.5 times in that analysis (fold change C vs. OOS). OOS, Ocoxin® oral solution.

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the antitumoral effect of OOS in SCLC using both in vitro and in vivo models. OOS induced a clear decrease in MTT metabolization, indicative of an antiproliferative/pro-apoptotic effect in the different SCLC-derived cell lines tested. Such a reduction was both time and dose dependent. Moreover, OOS reduced in vivo progression of tumors generated by injection of GLC-8 cells in mice. OOS treatment slowed down tumor growth without signs of major toxicity, since the weights of the control and treated mice were analogous, and no detectable changes in the behavior of the mice were observed.

To explore the mechanisms leading to such tumor growth reduction in vivo, several approaches were carried out. First, a general evaluation of tumor characteristics indicated that tumors from control or treated mice exhibited large necrotic/apoptotic areas in the central region of the tumor that is clearly related to the tumor nature, independently of the treatment. Moreover, microscopic inspection of the tumors showed that control tumors seemed to be more vascularized. In fact, treated tumors appeared to be more compact. The presence of blood vessels is extremely important for tumor growth, since those tumor masses larger than a few millimeters in size need these structures for correct nutrient/oxygen supply (25). To evaluate whether such a decrease in blood vessels affected critical oncogenic properties such as survival or proliferation, sections of the tumors were stained with markers of these biological processes. When tumors were stained with the proliferation marker Ki-67, a reduction in proliferating cells after OOS treatment was observed. In addition, a clear increase in cell death was detected under those same conditions after staining for apoptotic cell death by TUNEL. These results point to a combined pro-apoptotic as well as anti-proliferative action of OOS in the SCLC in vivo models.

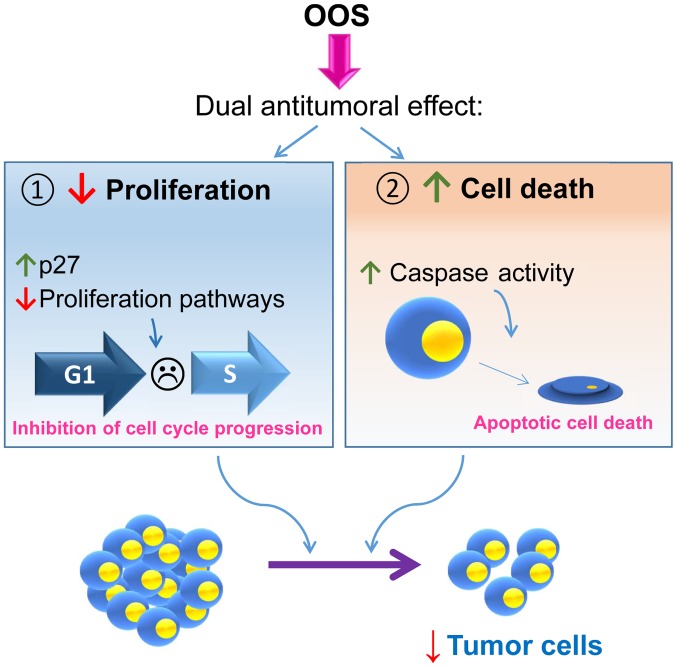

These in vivo mechanisms of action were confirmed in vitro, where OOS induced both cell death and cell cycle delay. This last action may result from a complex network that regulates cell proliferation, as suggested by the deregulation of several pathways that have been linked to the control of cell proliferation identified in the transcriptomic analyses (Fig. 6). Within such a network, one of the actual major players responsible for such anti-proliferative action appears to be the cell cycle inhibitory protein p27. These data corroborate previous studies in which p27 seems to be a key intermediate in OOS anti-proliferative action in other cellular systems such as breast cancer (13), hepatocarcinoma or acute myeloid leukemia (19,20).

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism of action of OOS in SCLC. OOS exhibits a dual mechanism of action on SCLC both in vitro and in vivo. OOS induces, on the one hand, an inhibition of cell proliferation due to an increase in the cell cycle inhibitory protein p27 and the deceleration of the cell cycle. Moreover, an increase in caspase-dependent cell death is also stimulated upon OOS treatment. The combination of both actions provokes a decrease in tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. OOS, Ocoxin® oral solution; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

The success of most antitumor therapies is based on the combination of different agents to increase the antitumor action of the individual agents. With this aim, OOS was used in combination with treatments commonly used in the clinic for SCLC, such as cisplatin, docetaxel or vincristine. When OOS was used together with these last two compounds, a clear potentiation of the antitumor properties was observed, opening the possibility of exploring such effect in patients. This is especially important since most of the patients suffer from metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis and, in those cases, only palliative chemotherapy is offered. For these patients, improvements in the standard of care treatment by the addition of other agents such as OOS could be beneficial as well as a very interesting therapeutic option.

Lung cancer represents the most lethal of all cancers worldwide. The lack of effective treatments, despite recent advances, calls for efforts to improve its management. OOS, which includes several vitamins and antioxidants, could have beneficial effects, always in adequate combination with standard of care therapies. To date, in this study a clear antitumoral effect of OOS on SCLC tumorigenesis has been demonstrated. Moreover, the dual action of the drug that inhibited cell cycle progression and also stimulated cell death may offer therapeutic benefit to the classical drugs used in lung cancer therapy. It would also be valuable to determine whether OOS exerts preventive action on SCLC using, if possible, genetic models for this disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain (BFU2015-71371-R) and Catalysis S.L. (Madrid, Spain). Our Cancer Research Institute and the work carried out at our laboratory receive support from the European Community through the Regional Development Funding Program (FEDER) and from the CRIS Cancer Foundation.

Competing interests

E.S. is an employee of Catalysis S.L. The research expenses for this study were partially supported by Catalysis S.L. (Madrid, Spain).

References

- 1.Riaz SP, Lüchtenborg M, Coupland VH, Spicer J, Peake MD, Møller H. Trends in incidence of small cell lung cancer and all lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:280–284. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, Read W, Tierney R, Vlahiotis A, Spitznagel EL, Piccirillo J. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: Analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4539–4544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahnert K, Kauffmann-Guerrero D, Huber RM. SCLC-state of the art and what does the future have in store? Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamson DW, Brignall MS. Antioxidants in cancer therapy; their actions and interactions with oncologic therapies. Altern Med Rev. 1999;4:304–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang CS, Chung JY, Yang G, Chhabra SK, Lee MJ. Tea and tea polyphenols in cancer prevention. J Nutr. 2000;130(Suppl 2):472S–478S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.472S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujiki H. Green tea: Health benefits as cancer preventive for humans. Chem Rec. 2005;5:119–132. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark J, You M. Chemoprevention of lung cancer by tea. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2006;50:144–151. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan N, Mukhtar H. Dietary agents for prevention and treatment of lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2015;359:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang W, Binns CW, Jian L, Lee AH. Does the consumption of green tea reduce the risk of lung cancer among smokers? Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4:17–22. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y, Yao R, Yan Y, Wang Y, Hara Y, Lubet RA, You M. A gene expression signature that can predict green tea exposure and chemopreventive efficacy of lung cancer in mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1956–1963. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadava D, Whitlock E, Kane SE. The green tea polyphenol, epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibits telomerase and induces apoptosis in drug-resistant lung cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:233–237. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández-García S, González V, Sanz E, Pandiella A. Effect of oncoxin oral solution in HER2-overexpressing breast cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2015;67:1159–1169. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2015.1068819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollman PC, Feskens EJ, Katan MB. Tea flavonols in cardiovascular disease and cancer epidemiology. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;220:198–202. doi: 10.3181/00379727-220-44365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L, Hudgins WR, Shack S, Yin MQ, Samid D. Cinnamic acid: A natural product with potential use in cancer intervention. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:345–350. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910620319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez EV, Perez YM, Sanchez HV, Forment GR, Soler EA, Bertot LC, García AY, del Rosario Abreu Vazquez M, Fabian LG. Antioxidant and immunomodulatory effects of Viusid in patients with chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2638–2647. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i21.2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Mahtab M, Akbar SM, Khan MS, Rahman S. Increased survival of patients with end-stage hepatocellular carcinoma due to intake of ONCOXIN®, a dietary supplement. Indian J Cancer. 2015;52:443–446. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.176699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dayem Uddin MAI, Mahmood I, Ghosha AK, Khatuns RA. Findings of the 3-month supportive treatment with ocoxin solution beside the standard modalities of patients with different neoplastic diseases. TAJ. 2009;22:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Díaz-Rodríguez E, Hernández-García S, Sanz E, Pandiella A. Antitumoral effect of ocoxin on acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:6231–6242. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Díaz-Rodríguez E, El-Mallah AM, Sanz E, Pandiella A. Antitumoral effect of Ocoxin in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:1950–1958. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huqun EY, Endo Y, Xin H, Takahashi M, Nukiwa T, Hagiwara K. A naturally occurring p73 mutation in a p73-p53 double-mutant lung cancer cell line encodes p73 alpha protein with a dominant-negative function. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:718–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postmus PE, de Ley L, van der Veen AY, Mesander G, Buys CH, Elema JD. Two small cell lung cancer cell lines established from rigid bronchoscope biopsies. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1988;24:753–763. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(88)90311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sher E, Pandiella A, Clementi F. Voltage-operated calcium channels in small cell lung carcinoma cell lines: Pharmacological, functional, and immunological properties. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3892–3896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cabrera N, Díaz-Rodríguez E, Becker E, Martín-Zanca D, Pandiella A. TrkA receptor ectodomain cleavage generates a tyrosine-phosphorylated cell-associated fragment. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:427–436. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med. 1995;1:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]