Abstract

Intussusception is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction in adults and represents a diagnostic challenge for the surgeon. In the majority of cases, presenting symptoms are not specific, making preoperative diagnosis difficult. Several medical conditions may cause intestinal intussusception. We present the case of a 16-year-old female patient with intussusception due to a hamartomatous Peutz–Jeghers type polyp. This is an extremely rare case in which the first manifestation of the intestinal polyp was jejunojejunal intussusception very close to the duodenojejunal junction, with a necrotic intussusceptum about 50 cm long. The patient was treated successfully with enterectomy and end-to-end anastomosis. Postoperative course was uneventful and the patient is currently under gastroenterological and genetic investigation to exclude the diagnosis of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.

Keywords: Intussusception, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Intestinal obstruction, Polyp

Introduction

Intussusception is defined as the condition in which part of the intestine slides with its mesenteric fold in the lumen of the adjacent distal bowel. This process impairs peristalsis, obstructs the free passage of the intestinal contents, compromises the mesenteric vascular flow of this part of the bowel and finally results in intestinal obstruction and inflammation of the bowel wall. Intussusception represents an uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction in adults, with a reported incidence of 1–5%. The ratio of adults to children is 1 : 20.1 Unlike in children, in adults only 10% of intestinal intussusceptions are idiopathic, whereas in the remaining 90% a demonstrable cause is revealed.2 In such cases, intussusception is associated with a lead point lesion, which may be a benign (adhesions, adenomatous polyp, Meckel’s diverticulum, hamartomatous polyp, lipoma, endometriosis, gastrointestinal stromal tumour, haemangioma, neurofibroma, tuberculosis) or a malignant mass (adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumor, leiomyosarcoma, lymphoma, metastatic carcinoma).1 Malignant lesions are responsible for up to 30% of cases of intussusception in the small bowel, whereas in the colon malignant aetiology is found in up to 66% of cases.2 We report the case of a 16-year-old female patient who presented with acute jejunojejunal intussusception and intestinal obstruction due to a Peutz–Jeghers type polyp.

Case history

A 16-year-old female patient with a clear medical history was admitted to our department complaining of diffuse abdominal pain, which had progressively aggravated during the previous three days. In addition, she mentioned anorexia, multiple episodes of bilious vomiting and diarrhoea. Upon presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: temperature 38.3 degrees C, arterial pressure 105/69 mmHg, heart rate 92 beats/minute, respiration 16 breaths/minute, SO2 98%. On physical examination the patient was pale. Palpation revealed epigastric and periumbilical tenderness no palpable abdominal mass, while on auscultation bowel sounds were diminished.

Laboratory tests revealed normal white blood cell count (6.9 × 103/mm3), iron deficiency anaemia and elevated C-reactive protein level. All other studies including electrolytes, liver function tests, glucose, serum creatinine, albumin and urinalysis were within normal limits. An erect abdominal x-ray showed dilated intestinal loops with multiple air fluid levels. Abdominal ultrasound revealed significantly distended small bowel loops with local cystic dilation.

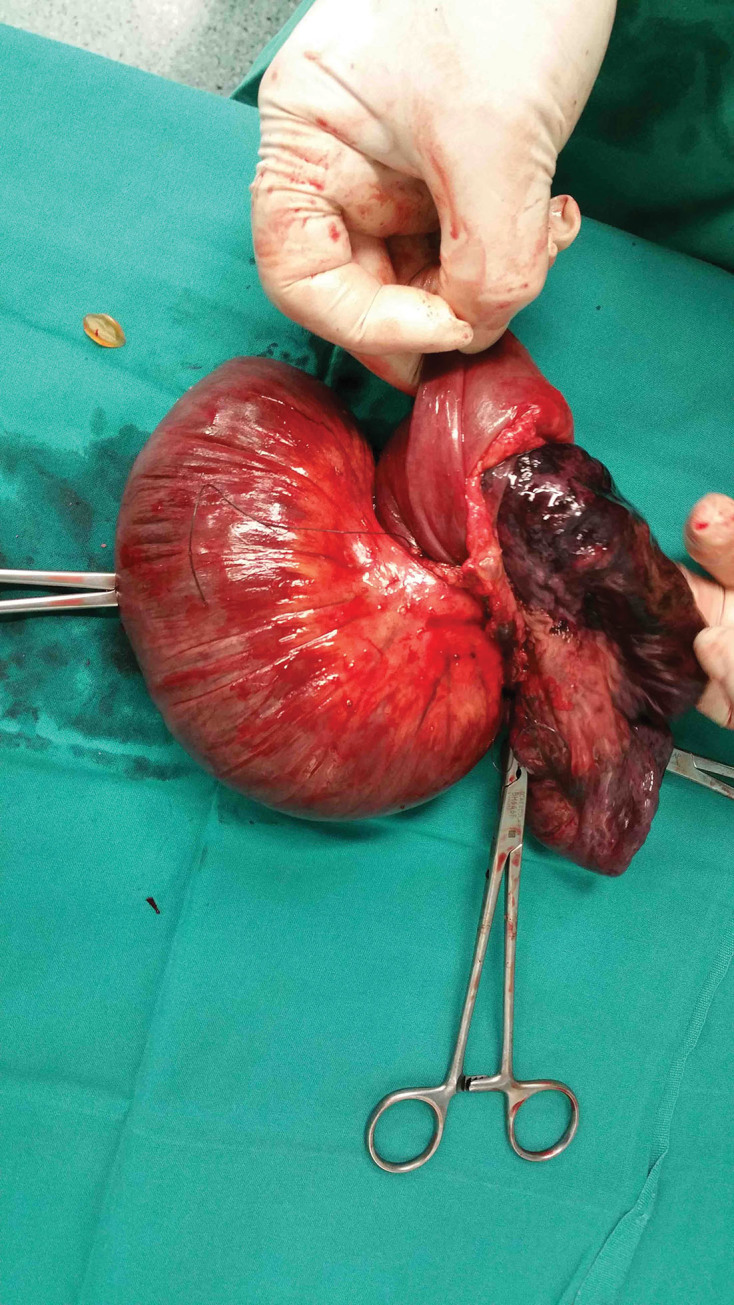

The patient underwent urgent exploratory laparotomy for a diagnosis of acute abdomen. An upper midline incision was used to gain access into the abdominal cavity. After entering the peritoneal cavity, a distended and ischemic part of jejunum was found approximately 10 cm away from the ligament of Treitz, resembling a small intestinal volvulus. After resection of the non-viable small bowel, intestinal continuity was restored with a hand-sewn end-to-end jejunojejunal anastomosis. After the excision of the ischemic intestine, jejunojejunal intussusception was finally identified with an intussusceptum measuring 50 cm in length (Figs 1 and 2). The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful and the she was discharged on the seventh postoperative day.

Figure 1.

Careful inspection of the surgical specimen after resection indicated intussusception as the true cause of intestinal obstruction in our patient

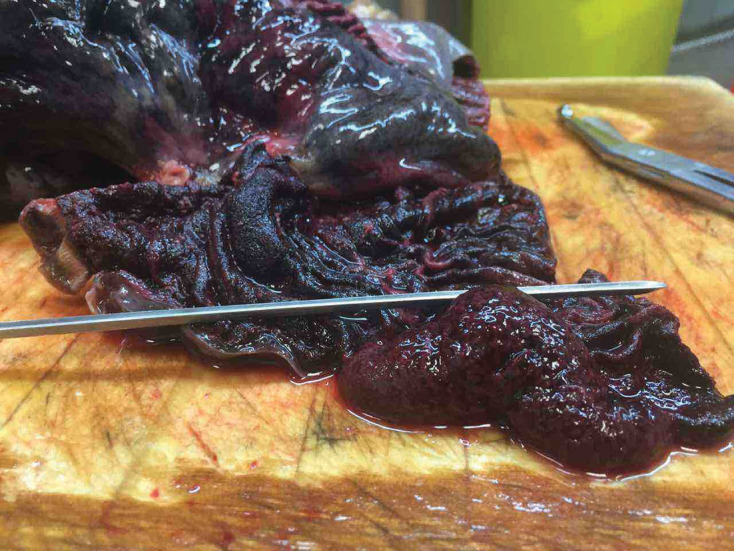

Figure 2.

The full length of the surgical specimen after manual reduction of the intussusception. Part of the affected bowel presents irreversible ischemic changes

Histopathological examination of the surgical specimen revealed a small polyp inside the necrotic intussusceptum, which was microscopically characterised as a benign hamartomatous Peutz–Jeghers like polyp (Fig 3). Given these findings, a detailed medical history was obtained and a comprehensive clinical examination undertaken, which failed to reveal either melanotic macules of the skin and oral mucosa or relevant family history. The absence of both family history and the typical clinical stigmata were not sufficient to rule out the diagnosis of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome. Consequently, the patient is currently under gastrointestinal and genetic investigation to rule out or confirm the diagnosis.

Figure 3.

Macroscopic view of the surgical specimen showing a small polyp inside the intussusceptum which acted as the lead point for intestinal intussusception

Discussion

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder characterised by gastrointestinal hamartomatous polyps in association with mucocutaneous hyperpigmentation. The incidence has been estimated to be 1 in 150.000 births.3 The cause has been proven to be a germline mutation on the serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11/LKB1) tumour suppressor gene on chromosome 19p13.3 in most cases (70-80%). The World Health Organization has laid down the following diagnostic criteria for Peutz–Jeghers syndrome:

three or more histologically confirmed Peutz–Jeghers polyps

any number of Peutz–Jeghers polyps with family history of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation with a family history of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

any number of Peutz–Jeghers polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.3

Our patient presented with neither mucocutaneous pigmentation nor positive family history and was therefore characterised as a case of solitary Peutz–Jeghers type hamartomatous polyp.

Peutz–Jeghers polyp is an unusual type of hamartomatous polyp, which is microscopically characterised by tree-like branching of smooth muscle fibres, with a core of smooth muscle arising from the muscularis mucosa and extending into the polyp, covered by mucosal tissue with near-normal appearance. It is unclear whether the presence of a solitary Peutz–Jeghers polyp in the intestine is considered to be an incomplete form of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome or a separate entity, because of the absence of clinical features and positive family history.4

Ultrasonography and computed tomography of the abdomen are very helpful imaging modalities for the diagnosis of intussusception.1 In our patient, abdominal ultrasonography was suggestive of intestinal intussusception but the diagnosis could not be established as the presence of air due to bowel distention limited the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound. Although computed tomography of the abdomen is the gold standard in diagnosing intussusception, with an accuracy of 85–100%, we decided to proceed with exploratory laparotomy, given the patient’s general condition.

The length of bowel involved in intussusception varies.5 In our case, the length of the intussusceptum was about 50 cm and it was necrotic. To the best of our knowledge this is the first case reported in literature with such a long intussusceptum.

In pediatric cases, reduction of the intussusception by barium enema, ultrasound-guided hydrostatic reduction or intraoperative reduction by manipulation is justified. It must be emphasised that reduction of jejunojejunal intussceceptions or indeed any small bowel event in adults is not generally performed as the lead point cannot usually be reached and attempts at pneumatic reduction in such cases are invariably unsuccessful. In our patient, reduction was not attempted as the bowel was friable and oedematous, thus posing a great risk for perforation with subsequent spillage of intestinal contents and perhaps tumour cells into the peritoneal cavity.1

In conclusion, surgeons treating patients with acute abdomen should always bear in mind that the presenting symptoms of intussusception are non-specific, thus making preoperative diagnosis difficult (< 50%) and in most cases delayed, leading to ischaemia and necrosis. In adult cases, the presence of underlying pathology usually necessitates resection rather than reduction.

References

- 1.Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD. Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. 2017; (1): 30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zubaidi A, Al-Saif F, Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. 2006; (10): 1,546–1,551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thakker HH, Joshi A, Deshpande A. Peutz-Jegher’s syndrome presenting as jejunoileal intussusception in an adult male: a case report. 2009; : 8,865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakayama H, Fujii M, Kimura A, Kajihara H. A solitary Peutz–Jeghers-type hamartomatous polyp of the rectum: report of a case and review of the literature. 1996; (4): 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozer A, Sarkut P, Ozturk E, Yilmazlar T. Jejunoduodenal intussusception caused by a solitary polyp in a woman with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a case report. 2014; : 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]