Abstract

Background

Dietary fibers are metabolized by gastrointestinal (GI) bacteria into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). We investigated the potential role of these SCFAs in β-amyloid (Aß) mediated pathological processes that play key roles in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis.

Research design and methods

Multiple complementary assays were used to investigate individual SCFAs for their dose-responsive effects in interfering with the assembly of Aß1-40 and Aß1-42 peptides into soluble neurotoxic Aß aggregates.

Results

We found that several select SCFAs are capable of potently inhibiting Aß aggregations, in vitro.

Conclusion

Our studies support the hypothesis that intestinal microbiota may help protect against AD, in part, by supporting the generation of select SCFAs, which interfere with the formation of toxic soluble Aß aggregates.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, beta-amyloid (Aβ), fibrils, protein misfolding, microbial, microbiome, microbiota, neurodegeneration

1. INTRODUCTION

The term intestinal microbiota refers to the tens of trillions of commensal, symbiotic, and pathogenic microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi and archaea, which live in our intestine. There is a growing interest in the potential contributions of intestinal microbiota, particularly among the intestinal bacterial population, in human health and/or disease [1]. There is tremendous diversity among individuals’ intestinal microbiota with respect to the composition of specific bacterial species and the density (number) of bacteria that are present for each of these bacterial species. Indeed, such interpersonal differences in intestinal bacteria composition have been associated with the presence or absence of an increasing number of health issues, including metabolic syndrome, obesity, immunological diseases, cardiovascular diseases, as well as neuro-degenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1–4].

Gastrointestinal (GI) bacteria may affect host functions by interfering with potential pathogens, improving barrier function, immunomodulation, and/or production of neurotransmitters [5]. GI bacteria may also affect host functions through diet-based microbial influences, by metabolizing dietary compounds into readily absorbable, biologically available, bioactive forms that are responsible for modulation of select biological processes [6]. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that such diet-based microbial influences may help promote resilience against diverse medical conditions, including neurological disorders such as AD, by modulation of metabolic and immunologic responses and/or other disease-specific pathological mechanisms [7–10]. An example of such diet-based microbial influence on neurodegenerative disorders is the critical role of gut microbiota in the bioactivity of dietary polyphenols. It has been estimated that about 90% of the dietary polyphenols are not absorbed by the small intestine and are accumulated in the colon where they are subjected to metabolism by GI microbial into phenolic acids, which are then readily absorbed [11,12]. Recent evidence revealed that some of these biologically available phenolic acids, such as caffeic acid and ferulic acid [13–16] are bioactive in inhibiting the generation of beta-amyloid (Aβ) peptides, a key pathogenic feature of AD [8], as well as in suppressing the elevated oxidative stress and inflammatory responses that are observed in AD as well as in other neurodegenerative disorders [9,10]. Moreover, our recent evidence revealed that other biologically available, GI microbiota-derived phenolic acids, such as 3-hydroxybenzoic acid and 3-(3´-hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid, are bioactive in interfering with the misfolding of Aβ peptides into neurotoxic Aβ aggregates that play key roles in AD pathogenesis [17]. Collectively, this evidence suggests that the GI microbiota may help attenuate the development and/or progression of AD through the generation of microbiota-derived phenolic compounds that mechanistically target diverse pathogenic mechanisms underlying AD.

Another example of diet-based microbial influence on AD is the involvement of GI microbials in the metabolism of dietary fibers. Dietary fibers are carbohydrate polymers, which cannot be hydrolyzed by the endogenous enzymes in the upper gut. Instead, dietary fibers are metabolized by the microbiota in the colon into short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) with 5 carbons or less, including valeric acid and isovaleric acid (C5), isobutyric acid and butyric acid (C4), propionic acid (C3), acetic acid (C2), and formic acid (C1) [18,19]. It has been hypothesized that SCFAs generated by GI bacterial metabolism of dietary fibers may attenuate AD by serving as substrates for energy metabolism [7], and providing an alternative energy source to rectify brain hypo-metabolism that contributes to neuronal dysfunctions in AD and other neurodegenerative conditions [20]. Recent evidence suggests that select SCFAs may also help modulate maturation and function of microglia in the brain [21], implicating the potential benefits of GI bacteria-derived SCFAs in modulating neuro-inflammatory processes that play important roles across diverse neurodegenerative disorders, including AD. More recently, it was shown that GI bacterial-mediated generation of butyric acid, an SCFA from dietary fibers, may provide therapeutic benefits for AD through epigenetic mechanisms of action by inhibiting histone deacetylase and normalizing aberrant histone acetylation in AD [22]. However, while neurotoxic Aβ aggregates play a central role in AD onset and progression, it is currently unknown whether GI bacteria-derived SCFAs may modulate protein misfolding. Therefore, we hereby investigate whether GI bacteria-derived SCFAs may help modulate the self-assembly of Aβ peptide, in vitro, using established assays. Outcomes from this study provide critical information for developing probiotics to help prevent and/or treat AD.

2. METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and Solvents

Chemicals were obtained from Sigma and, unless otherwise stated, were of the highest purity available. Solvents were HPLC grade and were obtained from Fisher. Water was double-distilled and deionized using a Milli-Q system (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA).

2.2. Peptides and Proteins

Monomeric Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 peptides were synthesized, purified, and characterized as described previously [23]. Purified peptides were stored as lyophilizates at −20 °C. A stock solution of glutathione S-transferase (GST; Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared by dissolving the lyophilizate to a concentration of 250 μM in 60 mM NaOH. Prior to use, aliquots were diluted 10-fold into 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4.

2.3. Preparation of Aβ Solutions

Aggregate-free Aβ1-40 or Aβ1-42 solutions were prepared as described previously [24]. To prepare Aβ, 200 μl of a 2 mg/ml peptide solution in dimethyl sulfoxide was sonicated for 1 min using a bath sonicator (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) and then centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000 × g. The resulting supernate was fractionated on a Superdex 75 HR column using 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The middle of the LMW peak was collected around 25 minutes and used immediately. A 10-μl aliquot was taken for amino acid analysis to determine quantitatively the peptide concentration in each preparation. Typically, the concentrations of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 were 30–40 and 10–20 μM, respectively.

2.4. Peptide Aggregation

Aggregation of Aβ1-40 (or Aβ1-42) peptide was conducted essentially as described previously [25]. In brief, Aβ solutions (0.5-ml aliquots) were placed in 1-ml microcentrifuge tubes. Test compounds (SCFAs) were dissolved in ethanol to a final stock concentration of 2.5 mM. Peptide aggregation was conducted in 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, with 5 μM Aβ1-40 (or Aβ1-42) peptide in the presence of either vehicle or individual SCFA a final 5 μM or 20 μM concentration, for a final SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 or 1:4. The tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 0 −10 days without agitation.

2.5. Photoinduced cross-linking of unmodified proteins (PICUP)

Aβ peptide oligomer frequency distributions were assessed using the photoinduced cross-linking of unmodified proteins protocol as described previously [25]. Briefly, 1 μl of 1 mM tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) (Ru(bpy)) and 1 μl of 20 mM ammonium persulfate were added to18 μl of freshly prepared protein solution. We noted that addition of SCFA did not lead to observable change in the pH of reaction mixture. The mixture was irradiated for 1 s with visible light, and then the reaction was quenched with 10 μl of Tricine sample buffer (Invitrogen) containing 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol. An aliquot (20 μl) of each cross-linked sample was electrophoresed on a 10–20% gradient Tricine gel and visualized by silver staining (SilverXpress, Invitrogen). Non-cross-linked samples were used as controls in each experiment. To produce intensity profiles and calculate the relative amounts of each oligomer type, Densitometry was performed, and One-Dscan software (v. 2.2.2; BD Biosciences Bioimaging) was used to determine peak areas of baseline corrected data.

2.6. Thioflavin T (ThT) spectroscopic assay

The ThT assay was conducted essentially as described previously [25]. Ten μl of sample was added to 190 μl of ThT dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and then the mixture was vortexed briefly. ThT fluorescence was determined three times at intervals of 10 s using an Hitachi F-4500 fluorometer. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 450 and 482 nm, respectively. Sample fluorescence was determined by averaging the three readings and subtracting the fluorescence of a ThT blank.

2.7. Electron Microscopy (EM)

To study protofibril formation and the effects of SCFAs on it, Aβ was incubated according to the aggregation protocol above. After incubation at 37 °C for 7 days in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, EM was used to determine the morphologies of Aβ1-40 or Aβ1-42 assemblies as described previously [25]. Briefly, a 10-μl aliquot of each sample was spotted onto a glow-discharged, carbon-coated Formvar grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and incubated for 20 min. The droplet then was displaced with an equal volume of 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in water and incubated for an additional 5 min. Finally, the peptide was stained with 8 μl of 1% (v/v) filtered (0.2 μM) uranyl acetate in water (Electron Microscopy Sciences). This solution was wicked off, and then the grid was air-dried. Samples were examined using a JEOL CX100 transmission electron microscopy.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effects of SCFAs on Aβ protein-protein interactions

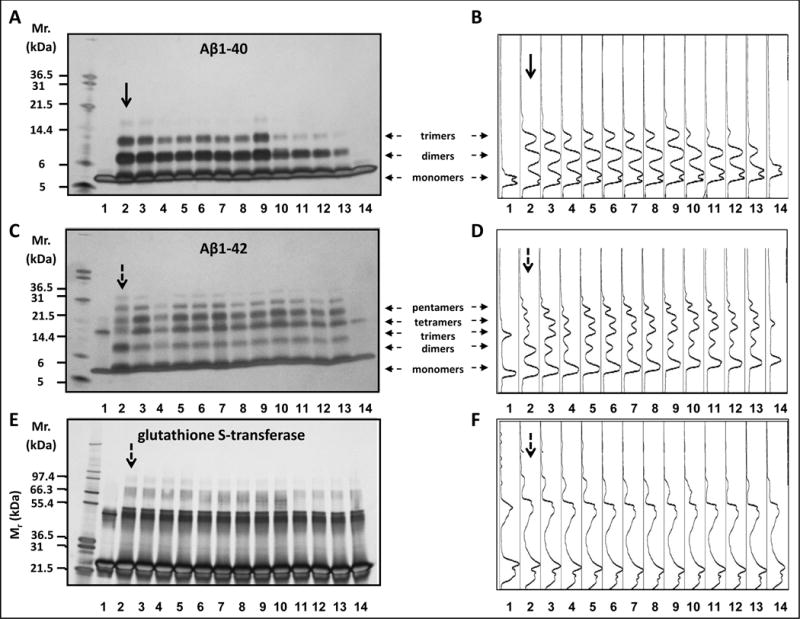

The self-assembly of Aβ peptides into neurotoxic soluble Aβ aggregates is one of the key neuropathological processes underlying AD. We used the PICUP assay to monitor the effect that individual SCFAs have in interfering with initial protein-protein interactions necessary for the assembly of Aβ1-40 or Aβ1-42 peptides into neurotoxic aggregates in the presence or absence of individual SCFAs at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 or 1:4. Six SCFAs were tested using the PICUP assay: valeric acid, isovaleric acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, propionic acid and acetic acid. Monomeric Aβ1-40 or Aβ1-42 peptides and cross-linked multimeric Aβ forms were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining.

In the absence of cross-linking, only Aβ1-40 monomers were observed (Fig. 1A-B, lane 1). As we have previously reported [27], cross-linking of Aβ1-40 in the absence of SCFAs leads to the formation of Aβ1-40 dimer and trimer forms (Fig. 1A-B, lane 2, indicated by black arrow). We observed that valeric acid potently interferes with initial Aβ1-40 protein-protein interactions. In particular, the addition of valeric acid at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 1A-B, lane 13) completely inhibited the formation of the trimeric Aβ1-40 form and partially inhibited the formation of the dimer Aβ1-40 form (compare lane 13 vs. lane 2). The addition of an increasing molar ratio of valeric acid with a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1 (Fig. 1A-B, lane 14) completely blocked the formation of into dimeric or trimeric Aβ1-40 forms (compare lane 14 vs. lane 2). Both butyric acid and propionic acid also interfered with Aβ1-40 oligomerization but to a lesser extent in comparison to valeric acid. In particular, butyric acid, at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 1A-B, lane 11) or 4:1 SCFA:Aβ (Fig. 1A-B, lane 12) almost completely inhibited the aggregation of Aβ1-40 monomers into Aβ1-40 trimers, but was not effective in modulating the formation of Aβ1-40 dimeric forms (compare lanes 11 and 12 vs. lane 2). Propionic acid, at a SCFA:Aβ ratio of 4:1 (Fig. 1A-B, lane 10) almost completely inhibited the generation of Aβ1-40 trimers) (compare lane 10 vs. lane 2). However, Aβ1-40 aggregation was not affected by the addition of a lower molar ratio of propionic acid, at a 1:1 SCFA:Aβ molar ratio (Fig. 1A-B, lane 9) (compare lane 9 vs. lane 2). The remaining three SCFAs monitored (isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid and acetic acid) had no observable impact on the conversion of monomeric Aβ1-40 peptide (Fig. 1A-B, lanes 3-8) into higher-ordered multimeric Aβ1-40 forms in our PICUP assay (compare lanes 3-8 vs. lane 2).

Figure 1.

Select SCFAs potently interfere with protein-protein interactions among Aβ peptides. (a, c, e) Monomeric, dimeric and higher-ordered cross-linked multimeric Aβ1-40 (a), Aβ 1-42 (c) or GST (e) aggregates were visualized by silver staining of the gel. Shown are representative assays from three independent studies. (b, d, f) Densitometry intensity profiles for Aβ1-40 (b), Aβ1–21 (d) and GST (f). In (a-f, lane 1) Aβ1-40 (a,b), Aβ1-42 (c,d) or GST (e,f) alone without cross-linking. In (a-f, lanes 2–14) Aβ1-40 (a,b), Aβ1-42 (c,d) or GST (e,f) with cross-linking in the presence of vehicle (lane 2) or in the presence of individual SCFSs as follow: isobutyric acid at a SCFA:Aβ (or GST) molar ratio of 1:1 (lane 3) or 4:1 (lane 4), isovaleric acid at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 (lane 5) or 4:1 (lane 6), acetic acid at a SCFA:Aβ (or GST) molar ratio of 1:1 (lane 7) or 4:1 (lane 8), propionic acid at a SCFA:Aβ (or GST) molar ratio of 1:1 (lane 9) or 4:1 (lane 10), butyric acid at a SCFA:Aβ (or GST) molar ratio of 1:1 (lane 11) or 4:1 (lane 12), valeric acid at a SCFA:Aβ (or GST) molar ratio of 1:1 (lane 13) or 4:1 (lane 14). In (a-d), horizontal arrows indicate monomers, dimers, trimers, tetramers and pentamers. In (a-f), vertical arrows indicate positive control studies in which Aβ1-40 (a-b), Aβ1-42 (c-d) or GST (e-f) were incubated in the absence of SCFA.

In the absence of cross-linking, monomeric Aβ1-42 shows up in a trimeric form under SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C-D, lane 1). The Aβ1-42 trimer band has been shown to be an SDS-induced artifact [26,27]. As we have previously reported [27], cross-linking of Aβ1-42 in the absence of SCFAs leads to the formation of Aβ1-42 oligomers of orders 2-6 (Fig. 1C-D, lane 2, indicated by black arrow). We observed that the addition of valeric acid, at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1 (Fig. 1C-D, lane 14), completely inhibited the formation of all Aβ1-42 oligomers (compare lane 14 vs. lane 2). However, Aβ1-42 aggregation was not affected by the addition of a lower molar ratio of valeric acid, at a 1:1 SCFA:Aβ molar ratio (Fig. 1C-D, compare lane 13 vs. 2). The conversion of Aβ1-42 monomers into higher-order multimeric forms was unaffected by the addition of butyric acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid, and acetic acid at either a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 or 4:1 (Fig. 1C-D, compare lanes 2-12 vs. lane 2).

In parallel, in the control PICUP study, which used glutathione S-transferase (GST) as a positive control for the cross-linking chemistry as we have used in the past [25], we observed that incubation of GST in the absence of SCFAs lead to the formation higher molecular weight GST aggregate forms (Fig. 1E-F, lane 2, indicated by a black arrow). We observed no alterations in GST cross-linking in the presence of SCFAs at a SCFA:GST molar ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 1E-F, compare lanes 3, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13 vs. lane 2) or 4:1 (Fig. 1E-F, compare lanes 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14 vs. lane 2). We therefore concluded that valeric acid, butyric acid and propionic acid inhibited Aβ1-40 and/or Aβ1-42 aggregation.

3.2. Effects of SCFAs on Aβ fibril formation

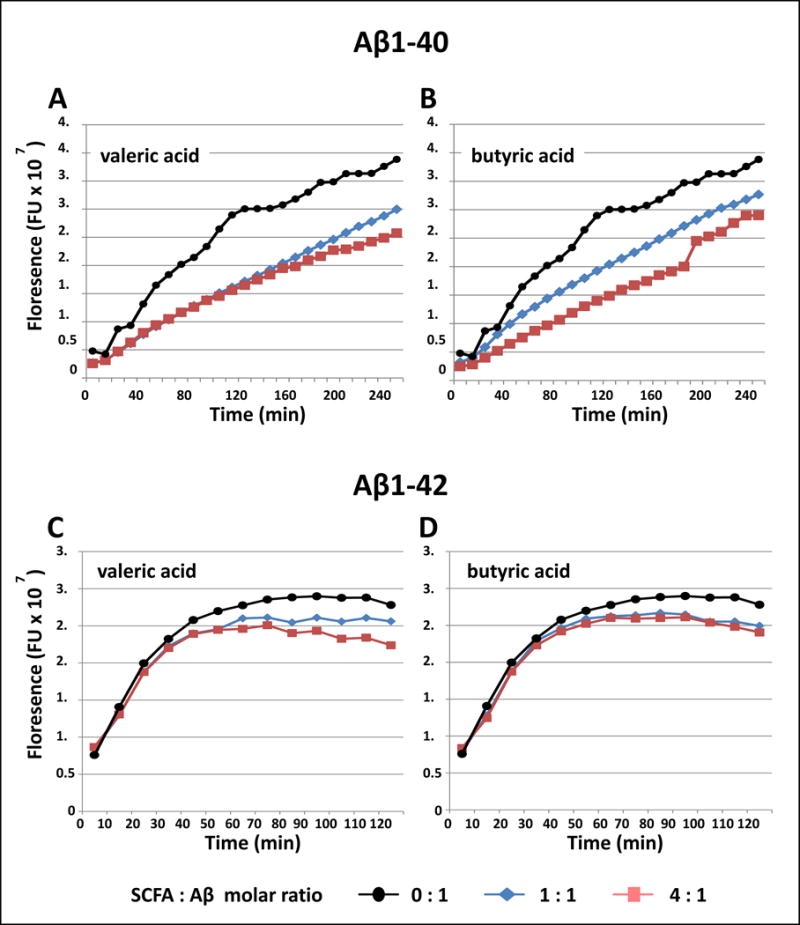

Based on the evidence from our PICUP assay, we continued by assessing valeric acid and butyric acid for their potential effects on the assembly of monomeric Aβ peptides into Aβ fibrils by using the ThT spectroscopic assay to monitor for temporal changes in β-sheet contents of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, which were incubated in the absence of SCFA (SCFS:Aβ molar ratio of 0:1) or in the presence of individual SCFAs at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 or 4:1. We note that ThT fluorescence is not a direct measure of fibril content. However, since β-sheet formation correlates with fibril formation, ThT fluorescence is a useful surrogate marker [28].

We observed that both valeric acid and butyric acid attenuated the conversion of Aβ1-40 monomers to Aβ1-40 fibrils with a dose-response efficacy; the higher dose of valeric acid or butyric acid (SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1) appeared more effective than the lower dose (SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1) (Fig. 2A,B). We found that valeric acid also attenuated the conversion of Aβ1-42 monomers to Aβ1-42 fibrils with a dose-response efficacy; the higher dose of valeric acid (SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1) appeared more effective than the lower dose (SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1) (Fig. 2C). Lastly, we observed that butyric acid treatment also displayed a tendency to reduce the formation of Aβ1-42 fibrils, but there are no observable differences between the lower and higher dose (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Select SCFAs potently interfere with Aβ fibril formation. Assembly of monomeric Aβ1-40 or Aβ 1-42 peptides into Aβ fibrils in the presence of valeric acid, butyric acid or vehicle were assessed using the ThT assay, which monitors ThT fluorescence as an indirect assessment of fibril contents. Periodically, aliquots were removed, and ThT binding levels were determined. Binding is expressed as mean fluorescence (in arbitrary fluorescence units (FU). (a-d) Aβ1-40 (a-b) or Aβ1-42 (c-d) were incubated for up to 240 min at 37°C in 10 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, in the presence of vehicle (), or in the presence of valeric acid (a,c) or butyric acid (b,d) at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1 () or 4:1 (). Shown are representative assays from three independent studies.

Collectively, our evidence demonstrates that valeric acid (and to a lesser extent, butyric acid) is capable of interfering with the conversion of monomeric Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 into Aβ fibrils.

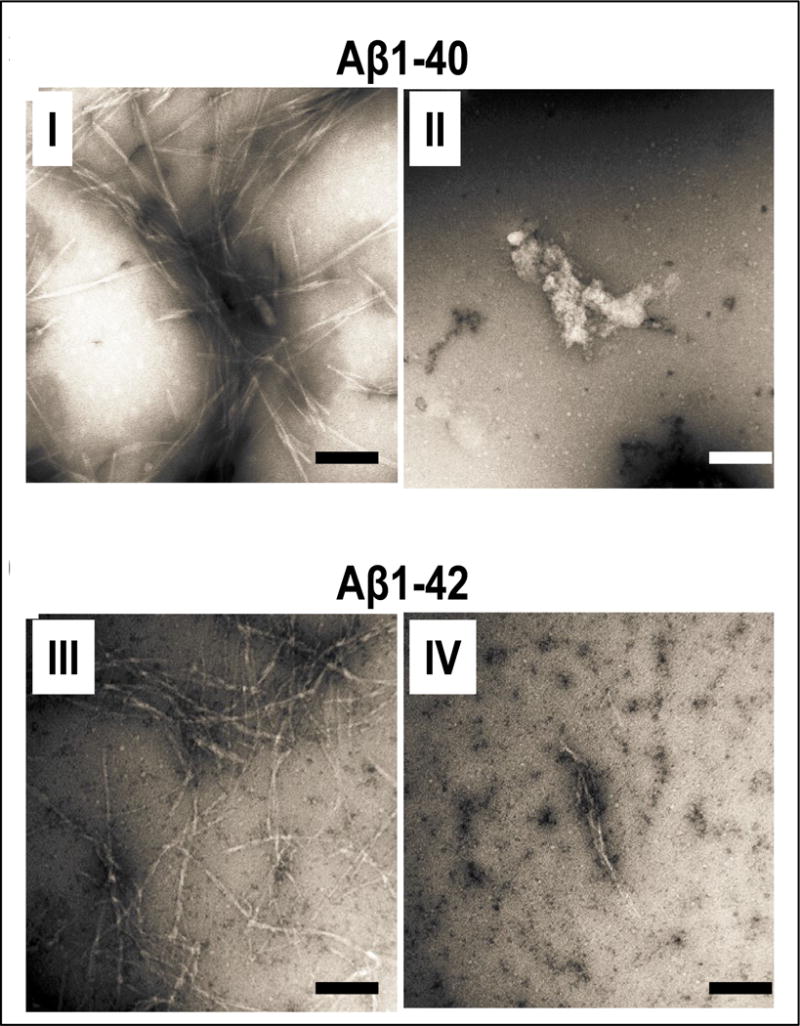

3.3. Effects of valeric acid on the morphologies of the Aβ assemblies

Our evidence from Figs. 1 and 2 demonstrating that, among the 6 SCFAs we tested, valeric acid most potently interferes with the aggregation of Aβ peptides into higher-ordered assemblies. Based on this, we continued and used EM to monitor for effects of valeric acid on the morphologies of the Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 assemblies. Consistent with our prior observations [25], the incubation of Aβ1-40 (Fig. 3, panel I) or Aβ1-42 (Fig. 3, panel III) in the presence of vehicle leads to the generation of classical non-branched fibrils with helicity features. Aβ incubation in the presence of valeric acid, at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1, almost completely inhibited fibril formation from Aβ1-40 (Fig. 3, panel II) or Aβ1-42 (Fig. 3, panel IV).

Figure 3.

Assessments of Aβ protofibril morphology. (Panels I, II, III, IV) EM was used to determine the morphologies of protofibrils obtained by the incubation of Aβ1-40 (panels I and II) or Aβ42 (panels III and IV), in the presence of vehicle (panels I and III) or valeric acid at a valeric acid:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1 (panels I and IV). Shown are representative assays from three independent studies. Scale bars indicate 100 nm.

4. DISCUSSION

The assembly of Aβ peptides into low-n oligomers requires initial protein-protein interactions among Aβ peptides. Our study is specifically designed to assess if a specific test compound is capable of interfering with such protein-protein interactions and therefore to disrupt the process Aβ assembly into low n neurotoxic oligomers. We used independent in vitro assays to investigate 6 SCFAs that are derived from GI-microbiota metabolism of dietary fibers for their potential effects in modulating the assembly of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 peptides to soluble, neurotoxic Aβ aggregates that play roles in AD pathogenesis. Results from our PICUP assays revealed that select SCFAs, particularly valeric acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid are capable of interfering with initial protein-protein interactions, which are necessary for Aβ assemblies (Fig. 1). In particular, valeric acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid demonstrated efficacy in interfering with protein-protein interactions that are necessary for the conversion of Aβ peptides to neurotoxic Aβ aggregates. The relative anti-Aβ aggregation efficacy of the three SCFAs are, in decreasing order, valeric acid >> butyric acid > propionic acid. In particular, valeric acid most potently inhibited protein-protein interaction of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42; the higher dose of valeric acid (at a SCFA:Aβ molar ratio of 4:1) interfering with the aggregation of both Aβ1-40 and 1-42 peptides. In comparison, the lower dose (at a valeric acid:Aβ molar ratio of 1:1) was effective in interfering with the aggregation Aβ1-40 into Aβ1-40 trimers, and to a lesser extent Aβ1-40 dimers, but was not effective in interfering with the aggregation of Aβ1-42. In contrast, butyric acid (at both the higher and lower dose) and propionic acid (at the higher dose) interfered with the formation of Aβ1-40 trimers, but not the formation of Aβ1-40 dimers. Moreover, neither butyric acid or propionic acid was effective in modulating the aggregation of Aβ1-40 peptides into higher-order aggregate forms. In contrast, three of the SCFAs tested (isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid, and acetic acid) had no observable effects on Aβ assemblies, as assessed by the PICUP assay. The efficacy of valeric acid and butyric acid in interfering with the assemblies of higher-ordered Aβ aggregate forms detectable by the PICUP assay is validated by observations from the independent ThT assay (Fig. 2). Consistent with results from our PICUP assays, we observed that valeric acid and butyric acid were effective in interfering with the assembly of Aβ1-40, and to a lesser extent, the assembly of Aβ1-42 into Aβ fibrils. The efficacy of valeric acid in interfering with the generation of Aβ fibrils was validated by the EM assay, which demonstrated that valeric acid inhibited the assembly of Aβ1-40 or Aβ1-42 into Aβ fibrils with classical non-branched fibrils with helicity features (Fig. 3). Collectively, results from our studies support the hypothesis that intestinal microbiota may have protective effects against AD, in part, by supporting the generation of select SCFAs that interfere with the formation of toxic soluble Aß aggregates. While the microbiota is known for generating SCFAs for dietary fibers, we also note that relatively minor amount of SCFA can be of dietary nature. Thus it is possible that dietary SCFA may also modulate Aβ aggregation independent of contribution from gastrointestinal microbiota.

The misfolding of disease-specific proteins into toxic aggregates is an important and common pathological mechanism underlying diverse neurological disorders. Aside from misfolding of Aβ peptides in AD, there are many other neurological disorders in which protein misfolding plays a crucial role is disease pathology, such as misfolding of α-synuclein in α-synucleinopathies such as PD, dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy, and misfolding of tau in tauopathies such as AD, dementia pugilistica, progressive supranuclear palsy, among others [29–32]. These aggregating proteins all share similar biophysical and biochemical properties that influence how they misfold, aggregate, and propagate in disease [33]. Thus, in addition to interfering with abnormal aggregation of amyloidogenic Aβ isoforms, valeric acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid may also similarly interfere with the assembly of α-synuclein and tau.

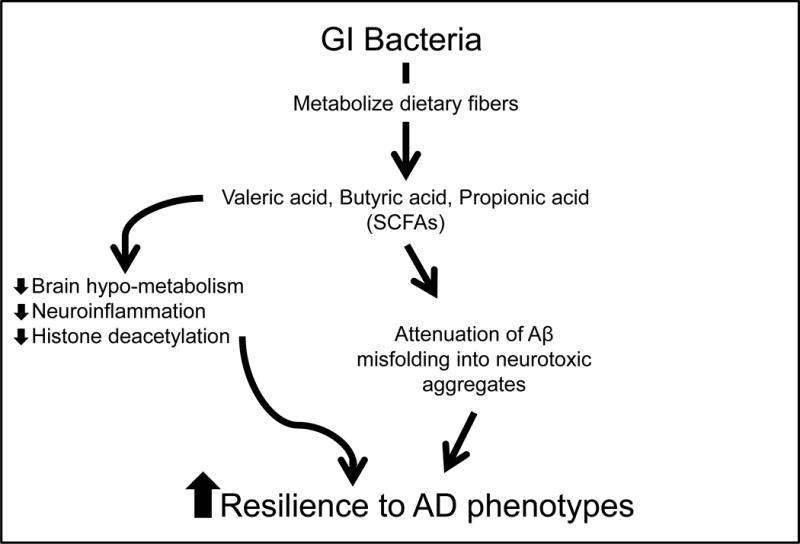

Accumulating published evidence suggests that GI bacteria may help promote resilience against AD through multiple mechanisms, the promotion of brain energy metabolism, modulation of neuro-inflammation, and modulation of epigenetic mechanisms (see Fig. 4). Our evidence revealed that GI bacteria may also improve AD by supporting the generation of select SCFAs that are capable of interfering with the assembly of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 peptides into neurotoxic Aβ aggregates (see Fig. 4). Future in vivo studies will be necessary to clarify whether certain SCFAs may attenuate AD β-amyloidosis through additional mechanisms.

Figure 4.

Schematics summarizing the mechanisms by which GI microbial-derived SCFAs may modulate AD. Intestinal bacteria help protect against AD by converting dietary fibers into biologically available SCFAs, which may promote resilience to AD through multiple cellular/molecular mechanisms. Previously published evidence suggests SCFAs may benefit AD by: (1) alleviating brain hypo-metabolism as SCFAs provide alternative substrates for brain energy metabolism [20], (2) attenuating neuro-inflammation by modulating the maturation and function of microglia in the brain [5], and (3) inhibiting histone deacetylases and normalize aberrant histone acetylation in the AD brain [7,14,34]. In addition, evidence from the present study suggests that certain SCFAs, particularly valeric acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid, may also benefit AD by attenuating Aβ-mediated pathologic processes by interfering with the assembly of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 peptides into neurotoxic Aβ aggregates.

5. CONCLUSION

Our observations provide the impetus for new investigations to identify and characterize select dietary fibers that support the generation of valeric acid, butyric acid, and propionic acid, as well as GI microbial that are capable of metabolizing dietary fibers to the these SCFAs. Information gathered will lead to the development of next-generation probiotics that might help promote resilience to diverse neurodegenerative disorders.

KEY ISSUES.

The studies suggest that select bacterial species that support conversion of dietary fibers to short-chain fatty acids, which are relevant to neurodegenerative conditions.

Our observation links gastrointestinal microbiota with mechanisms underlying AD-type Aβ neuropathological mechanisms.

Our observations suggest the feasibility of developing valeric acid for treating AD.

Misfolding of diverse proteins in multiple neurological disorders, such as Aβ in Alzheimer’s disease, tau in tauopathies, α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease, all share common mechanistic features. Our observation supports the potential development of valeric acid for treating these diverse neurological disorders.

Our observations support further investigations to identify and characterize gastrointestinal bacterial specie(s) that support the generation of valeric acid.

Our observations also support further investigations to characterize select dietary fiber preparations that supports the generation of valeric acids.

Information from the study will lead to the development of next-generation probiotics that might help promote resilience to diverse neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported in part by Grant Number P50 AT008661-01 from the NCCIH and the ODS. GM Pasinetti holds a VA Career Scientist Award. The authors acknowledge that the contents of this study do not represent the views of the NCCIH, the ODS, the NIH, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

References

- 1.Li D, Wang P, Wang P, et al. The gut microbiota: a treasure for human health. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34(7):1210–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PA, et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson’s disease and clinical phenotype. Mov Disord. 2015;30(3):350–358. doi: 10.1002/mds.26069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherwin E, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Recent developments in understanding the role of the gut microbiota in brain health and disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1111/nyas.13416. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu SC, Cao ZS, Chang KM, et al. Intestinal microbial dysbiosis aggravates the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in Drosophila. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):24. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00040-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez B, Delgado S, Blanco-Miguez A, et al. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(1):1600240. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, et al. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(6):1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(9):2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mori T, Koyama N, Guillot-Sestier MV, et al. Ferulic acid is a nutraceutical β-secretase modulator that improves behavioral impairment and Alzheimer-like pathology in transgenic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e5574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oboh G, Agunloye OM, Akinyemi AJ, et al. Comparative study on the inhibitory effect of caffeic and chlorogenic acids on key enzymes linked to Alzheimer’s disease and some pro-oxidant induced oxidative stress in rats’ brain-in vitro. Neurochem Res. 2013;38(2):413–419. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0935-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Wang Y, Li J, et al. Effects of caffeic acid on learning deficits in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Med. 2016;38(8):869–875. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifford MN. Diet-derived phenols in plasma and tissues and their implications for health. Planta Med. 2004;70(12):1103–1114. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-835835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monagas M, Uri-Sarda M, Sanchez-Patan F, et al. Insights into the metabolism and microbial biotransformation of dietary flavan-3-ols and the bioactivity of their metabolites. Food Funct. 2010;1(3):233–253. doi: 10.1039/c0fo00132e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vetrani C, Rivellese AA, Anuzzi G, et al. Metabolic transformations of dietary polyphenols: comparison between in vitro colonic and hepatic models and in vivo urinary metabolites. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;33:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menendez JA, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, et al. Analyzing effects of extra-virgin olive oil polyphenols on breast cancer-associated fatty acid synthase protein expression using reverse-phase protein microarrays. Int J Mol Med. 2008;22(4):433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie L, Lee SG, Vance TM, et al. Bioavailability of anthocyanins and colonic polyphenol metabolites following consumption of aronia berry extract. Food Chem. 2016;211:860–868. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadeghi ES, Sleno L, Sabally K, et al. Biotransformation of polyphenols in a dynamic multistage gastrointestinal model. Food Chem. 2016;204:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.02.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Ho L, Faith J, et al. Role of intestinal microbiota in the generation of polyphenol-derived phenolic acid mediated attenuation of Alzheimer’s disease β-amyloid oligomerization. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2015;59(6):1025–1040. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macfarlane GT, Macfarane S. Bacteria, colonic fermentation, and gastrointestinal health. J AOAC Int. 2012;95(1):50–60. doi: 10.5740/jaoacint.sge_macfarlane. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings JH, Pomare EW, Branch WJ, et al. Short chain fatty acids in human large intestine, portal, hepatic and venous blood. Gut. 1987;28(10):1221–1227. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.10.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zilberter Y, ZIlberter M. The vicious circle of hypometabolism in neurodegenerative diseases: ways and mechanisms of metabolic correction. J Neurosci Res. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jnr.24064. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erny D, Hrabe de Angelis AL, Jaitin D, et al. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:96–5977. doi: 10.1038/nn.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martins IJ, Binosha Fernando WMAD. High Fiber Diets and Alzheimer’s Disease. Food and Nutr Sci. 2014;5(4):410–424. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh DM, Lomakin A, Benedek GB, et al. Amyloid beta-protein fibrillogenesis. Detection of a protofibrillar intermediate. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(35):22364–22372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teplow DB. Preparation of amyloid beta-protein for structural and functional studies. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:20–33. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ono K, Condron MM, Ho L, et al. Effects of grape seed-derived polyphenols on amyloid beta-protein self-assembly and cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(47):32176–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806154200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bitan G, Fradinger EA, Spring SM, et al. Neurotoxic protein oligomers – what you see is not always what you get. Amyloid. 2015;12(2):88–95. doi: 10.1080/13506120500106958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bitan G, Tarus B, Vollers SS, et al. A molecular switch in amyloid assembly: Met35 and amyloid beta-protein oligomerization. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(50):15359–15365. doi: 10.1021/ja0349296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeVine H. Quantification of beta-sheet amyloid fibril structures with thioflavin T. Methods Enzymol. 1999;309:274–284. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)09020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar V, Sami N, Kashav T, et al. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative diseases: from theory to therapy. Eur J Med Chem. 2016;124:1105–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shamsi TN, Athar T, Parveen R, et al. A review on protein misfolding, aggregation and strategies to prevent related ailments. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.07.116. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forloni G, Artuso V, La Vitola P, et al. Oligomeropathies and pathogenesis of Alzheimer and Parkinson’s diseases. Mov Disord. 2016;31(6):771–781. doi: 10.1002/mds.26624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pula JH, Kim J, Nichols J. Visual aspects of neurologic protein misfolding disorders. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(6):482–489. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283319899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ugalde CL, Finkelstein DI, Lawson VA, et al. Pathogenic mechanisms of prion protein, amyloid-β and α-synuclein misfolding: the prion concept and neurotoxicity of protein oligomers. 2016;139(2):162–180. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plagg B, Ehrlich D, Kniewallner KM, et al. Increased acetylation of histone H4 at lysine 12 (H4K12) in monocytes of transgenic Alzheimer’s mice and in human patients. 2015;12(8):752–760. doi: 10.2174/1567205012666150710114256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]