ABSTRACT

Arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are abnormal shunts between the arterial and venous vascular systems. These usually produce ocular pain, increased intraocular pressure (IOP), and diplopia. Less frequently, they may cause retinal changes with visual impairment. Our purpose is to illustrate different retinal manifestations of AVF. We report the multimodal imaging study of three cases with retinal changes due to AVF, showing neurosensory retinal detachment, macular oedema, and macular ischemia. In conclusion, AVF may appear with different ophthalmic alterations. While usually increased IOP and diplopia are our main concerns, retinal study is mandatory, since a myriad of morphologic abnormalities might be present.

KEYWORDS: Arteriovenous fistula, carotid-cavernous fistula, macula, OCT, optical coherence tomography

Introduction

Intracranial arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) represent abnormal shunts between the arterial and venous vascular systems, commonly between the carotid artery and the cavernous venous sinus. AVF usually presents with engorgement of episcleral and conjunctival vessels, headache, increased intraocular pressure (IOP), and visual alterations such as diplopia. Most of these patients have no fundus alterations or just some degree of vascular tortuosity.

Case reports

Herein, we present three cases of intracranial AVF with visual impairment due to significant retinal changes, showing the importance of retinal examination in these patients. These are three cases out of 16 visited in the last 5 years in our centre, so a prevalence of 18.75% is estimated regarding the presence of significant retinal changes in patients with AVF.

Case 1

A 61-year-old man presented with diplopia of 48 hours of evolution and bilateral eyelid oedema and eye redness. Visual acuity (VA) was 20/20 in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination revealed engorged episcleral vessels and diffuse chemosis of both eyes. Applanation IOP was 28 mm Hg in his right eye and 16 mm Hg in his left eye. Dilated fundus examination was unremarkable. Subtle palsy of the VI right cranial nerve could be observed. Right carotid-cavernous fistula was diagnosed through magnetic resonance imaging. Two months later, VA decreased to 20/40 in his right eye and 20/60 in his left eye. Increased vessel engorgement and VI right cranial nerve paralysis was evidenced. Multifocal neurosensory detachment of the retina was observed with vascular tortuosity in both eyes (Figure 1). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans revealed multiple neurosensory detachments, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) irregularity, and irregular and thickened choroid. This condition, both the macular alterations and the AVF, spontaneously regressed, leading to 20/20 VA in both eyes and normal macular OCT after 3 months (Figure 2). Complete follow-up was 1-year.

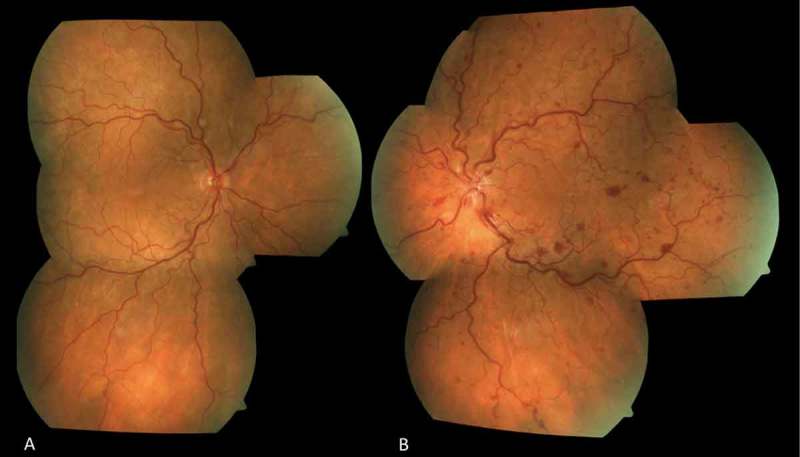

Figure 1.

Patient 1. Colour fundus photograph. (A) Right eye: Vascular tortuosity and multiple small serous retinal detachments can be observed. (B) Left eye: Vascular tortuosity, multiple retinal haemorrhages, multiple small serous retinal detachments, a big detachment with macular oedema, and disc oedema with splinter haemorrhages can be observed within the posterior pole.

Figure 2.

Patient 1. Optical coherence tomography scans of the macula. (A) Serous retinal detachment and intraretinal cysts. Irregular retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)–choriocapillaris surface. (B) Resolved serous detachment and retinal oedema, RPE–choriocapillaris irregularity still present (C) Complete resolution of serous detachment, retinal oedema, and RPE–choriocapillaris irregularity.

Case 2

A 58-year-old woman, angiographycally diagnosed with left dural AVF 1 week ago, complaints of loss of VA in her left eye (hand motion). Applanation IOP was 20 mm Hg in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination revealed engorged and tortuous episcleral vessels and conjunctival chemosis. Fundus examination revealed macular oedema, haemorrhages, and disc oedema. Macular OCT scans confirmed the macular oedema; increased choroidal thickness could also be observed. Due to the appearance of retinal vein occlusion (RVO) and presence of macular oedema, an intravitreal injection of ranibizumab was administered, achieving complete resolution after 1 month and no recurrence of the oedema in a 10-month follow-up (Figure 3). In this case, choroidal thickness could be measured, decreasing 134 μm in the first month. VA improved to 20/25 in her left eye. The AVF received no treatment and progressively improved.

Figure 3.

Patient 2. Optical coherence tomography scans of the macula. (A) Symmetric cystoid macular oedema. Small volume of subretinal fluid. Choroidal thickness measured 374 μm. (B) Complete resolution of the macular oedema and residual hyperreflective dots in different retinal layers. Choroidal thickness measured 240 μm.

Case 3

A 50-year-old man, angiographycally diagnosed with right carotid-cavernous fistula 1 month ago, complaints about pain and vision loss in his right eye. VA was 20/100 in his right eye and 20/60 in his left eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed engorged episcleral vessels. Applanation IOP was 18 mm Hg in both eyes. Dilated fundus examination revealed the presence of peripapillary cotton wool spots and isolated retinal haemorrhages (Figure 4A). Macular OCT scans showed mild changes in the inner retinal layers (Figure 4B). Eight weeks later, VA decreased to 20/200 in his right eye, exudates increased and diffuse retinal haemorrhages appeared. Macular OCT revealed oedema of the inner retinal layers with hyperreflective dots in these layers, demonstrating arterial retinal ischemia (Figure 4C). During the 8-month follow-up, VA and fundus features did not improve. No ocular or systemic treatment was performed due to refusal of the patient.

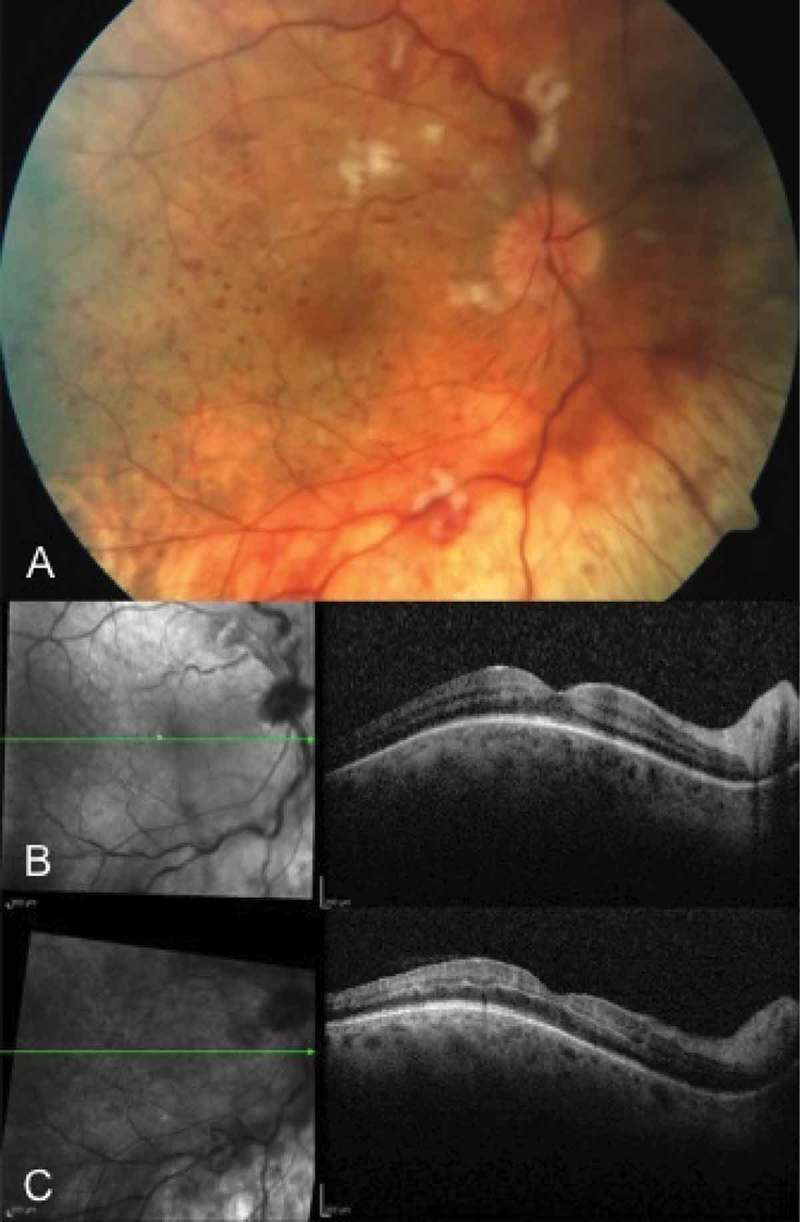

Figure 4.

Patient 3. (A) Colour fundus photograph. Right eye: Tessellation, vascular tortuosity, cotton wool spots, and intraretinal haemorrhages can be observed. (B) Optical coherence tomography scan of the macula. Mild changes in the inner retinal layers. (C) Optical coherence tomography scan of the macula. Oedema of the inner retinal layers secondary to arterial ischemia can be observed.

Discussion

The AVFs represent abnormal communications between the arterial and venous vascular networks. Intracranial AVFs manifest with periocular pain, episcleral and conjunctival vascular engorgement, chemosis, diplopia, and increased IOP, and they may eventually cause retinal signs due to venous stasis, including exudative retinal detachments, retinal venous occlusions, or optic neuropathies.1 We report three cases illustrating retinal alterations.

The presence of serous retinal detachments could be due to venous stasis, dysfunction of the choriocapillaris and the RPE, and subsequent appearance of subretinal fluid. This was previously described by Garg et al., who reported a case of macular detachment in a patient with a dural cavernous sinus fistula, which evolved to complete resolution of the detachment and improvement of VA.2 De Dompablo et al. also described a case with recurrent macular detachment with associated pigment epithelium detachments in the context of a carotid-cavernous fistula.3

RVO and secondary macular oedema are also part of the retinal features that may develop in AVF. This probably happens due to venous stasis and can lead to retinal ischemia. Komiyama et al. already described the association of carotid-cavernous sinus fistula and central RVO.4

Intravitreal antiangiogenic agents, such as ranibizumab, have been widely used in cases of macular oedema, particularly secondary to RVO. In our case, the clinical picture similar to RVO, leads us to recommend this treatment. In cases of AVF, the use of this treatment has only been described in the context of optic disc neovascularization secondary to traumatic, direct carotid-cavernous fistula, demonstrating complete regression.5 In the first case, a similar clinical picture to RVO could also be observed, but, since it appeared simultaneously to a general worsening of the other ophthalmic alterations associated to the AVF, observation was decided.

AVFs can also lead to retinal arterial ischemia. Pierre Filho et al. reported a case of central retinal artery occlusion in a patient with traumatic carotid cavernous fistula.6

Choroidal changes have also been studied. It has been published that choroidal thickness increases in cases of AVF, decreasing after its closure.7 In our report, choroidal thickness could only be measured in the second case, and we measured a decrease in 134 μm during our follow-up, as previously published.

Increased IOP and presence of diplopia are usually our main concerns, and fundus evaluation frequently takes place on a secondary level of importance. With these cases, we illustrate that retinal changes should also be part of the spectrum of complications we should think about, while evaluating patients with intracranial AVFs.

Conclusion

Intracranial AVFs may appear with a variety of ophthalmic alterations. While increased IOP and diplopia are the main potential concerns, the status of the retina should always be assessed, since we can find many other signs, such as serous retinal detachments, macular oedema, or ischemia. Macular OCT is a valuable tool to diagnose and monitor these changes.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- 1.Jorgensen JS, Guthoff R.. Ophthalmoscopic findings in spontaneous carotid cavernous fistula: an analysis of 20 patients. 1988;226:34–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02172714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg SJ, Regillo CD, Aggarwal S, Bilyk JR, Savino PJ.. Macular exudative retinal detachment in a patient with a dural cavernous sinus fistula. 2006;124(8):1201–1202. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.8.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Dompablo E, Díez-Álvarez L, Ruiz-Casas D, Sánchez-Gutiérrez V, Ciancas E, González-López JJ. Desprendimiento neurosensorial macular recurrente en fístula carótido-cavernosa. 2015;90(7):331–334. doi: 10.1016/j.oftal.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komiyama M, Yamanaka K, Nagata Y, Ishikawa H. Dural carotid-cavernous sinus fistula and central retinal vein occlusion: a case report and a review of the literature. 1990;34(4):255–259. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(90)90137-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saatci AO, Selver OB, Men S, Bajin MS. Single intravitreal ranibizumab injection for optic disc neovascularisation due to possibly traumatic, direct carotid cavernous fistula. 2014;97(1):90–93. doi: 10.1111/cxo.2014.97.issue-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierre Filho P, Medina FM, Rodrigues FK, Carrera CR. Central retinal artery occlusion associated with traumatic carotid cavernous fistula: case report. 2007;70(5):868–870. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492007000500026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinohara Y, Kashima T, Akiyama H, Kishi S. Alteration of choroidal thickness in a case of carotid cavernous fistula: a case report and review of the literature. 2013;13:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2415-13-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]