Abstract

Introduction

Non-vital bleaching is a non-invasive technique to treat the intrinsic discoloration of teeth of several etiologies. Hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate are commonly used bleaching agents.

Aim

The aim of this case report is to demonstrate the non-vital bleaching technique in maxillary anterior teeth.

Method

Maxillary central incisors were isolated with rubber dam and root canal treatment was performed. Barrier space preparation was done using a heated instrument. Glass ionomer cement was used a barrier material. Mixture of hydrogen peroxide and sodium perborate was placed in the canal and sealed with intermediate restorative material. After 1 week, the procedure was repeated to achieve the desired results.

Conclusion

Non-vital bleaching is a minimally invasive procedure to restore the esthetics of a discolored non-vital tooth. However, care should be taken to prevent any post-operative complications.

Keywords: bleaching, nonvital teeth, walking bleach technique

Introduction

Several intrinsic and extrinsic factors can cause changes in tooth color [1]. Intrinsic discoloration of the tooth can be caused following trauma, loss of vitality, endodontic treatment, and restorative procedures apart from known local and systemic factors [2]. Extrinsic staining, also called external staining, is mainly due to environmental factors including smoking, beverages and foods, antibiotics, and metals such as iron or copper [3]. Tooth bleaching, veneering or placement of a full coverage crown are treatment options for discolored tooth.

Non-vital teeth that are extensively discolored are highly receptive for bleaching techniques. A proper cervical barrier placement and an apical seal is necessary to prevent the percolation of bleaching agents into the periradicular tissues to avoid undesirable post-operative complications. If apical seal is improper a retreatment should be considered before proceeding ahead with the non-vital bleaching technique.

There are very few case reports demonstrating non-vital bleaching techniques mainly due to the fear of invasive cervical resorption that may occur due to improper barrier placement. Our case report is aimed to fill the existing void.

Case Report

A 25-year-old female patient reported to the department of conservative dentistry and endodontics with the chief complaint of unaesthetic appearance in upper anterior tooth region. Patient had a history of trauma 5 years back. On intraoral examination, tooth #11 and #21had pink discoloration (Figure 1). Tenderness to percussion was negative. Cold testing was done with cold spray (Endo-Frost, Coltene, Germany) on all the maxillary anterior teeth which confirmed that both #11 and #21 were non-vital. Radiographic examination was done which revealed no periradicular changes with the concerned teeth (Figure 2)

Figure 1.

Preoperative intraoral photograph showing discoloration with #11 #21.

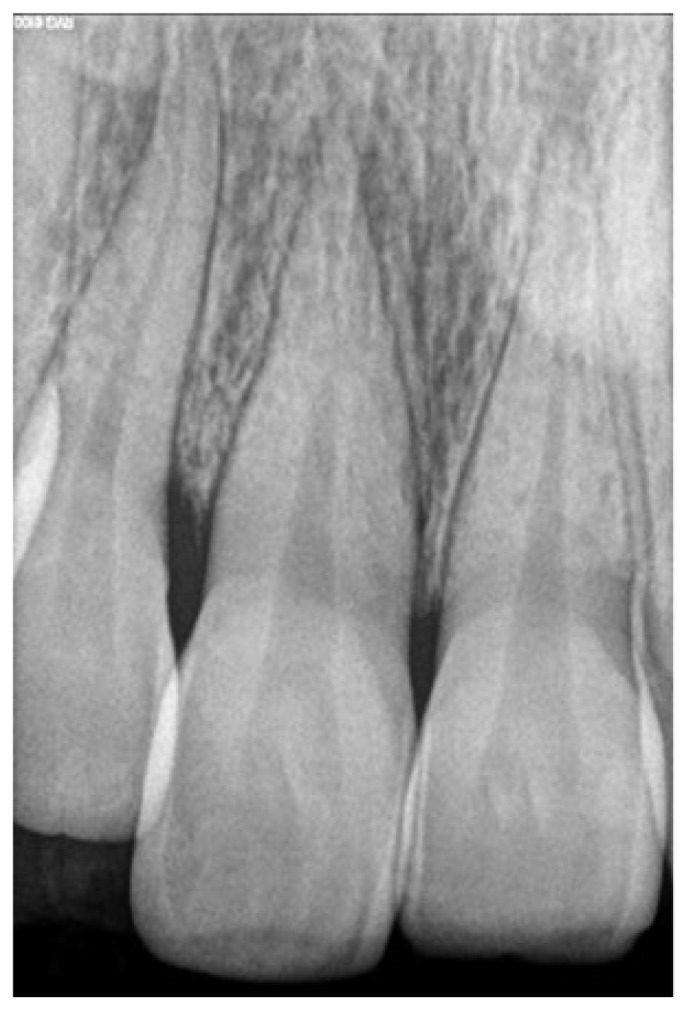

Figure 2.

Preoperative intraoral radiovisiograph showing no periradicular lesion.

Patient was informed about all the restorative options after endodontic therapy like bleaching, laminates or crown placement. Treatment plan was decided to do a non-surgical root canal treatment followed by non-vital bleaching of the involved teeth. In the first sitting, local anesthesia was administered and access cavity was made on #11 and #21 on the palatal side with a no. 4 round bur. Working length was established with a #25K file (Mani Inc, Japan) and confirmed with an apex locator (Root ZX mini, J Morita, USA). Biomechanical preparation with hand protaper size F2 (Dentsply Maillefer, USA). Abundant amount of normal saline and sodium hypochlorite were used as irrigants during the cleaning and shaping procedure. Canals were dried with paper points. Root canal filing was done with cold lateral compaction technique. Following root canal filing, 2 mm of gutta-percha was removed beyond the cemento-enamel junction (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Intraoperative radiovisiograph showing barrier placement under rubber dam isolation.

Post removal of gutta-percha, a 2 mm thick layer of glass ionomer cement (3M ESPE, USA) was placed over the gutta-percha as a barrier material. The chamber was etched with 37% phosphoric acid (Total Etch, Ivoclar Vivadent, Liechtenstein) for 30 seconds and it was washed and dried. Sodium perborate tetrahydrate and 30% hydrogen peroxide mixture was formed (1gm powder with 0.5ml liquid) and it was placed in the pulp chamber and condensed with a wet cotton pellet. Dry cotton was tightly placed over this the access cavity was sealed with cavit. The patient was recalled after 1 week for assessment. At a week visit, both #11 and #21 showed definite improvement in appearance except near the middle third of the tooth which still showed discoloration (Figure 4). Hence, the bleaching procedure was repeated and the patient was recalled again after 1 week to assess the bleaching results (Figure 5). Discoloration was completely removed and shade of the patient was enhanced. The sodium perborate – hydrogen peroxide mixture was removed from the pulp chamber using abundant saline and the access cavity was sealed with resin modified glass ionomer cement (Cention N, Ivoclar Vivadent) (Figure 6). A 1.5year intraoral follow up image shows no signs of pathology. (Figure 7)

Figure 4.

Photograph showing one week follow up. Discoloration present in middle third of teeth #11 #21.

Figure 5.

Photograph showing two weeks follow up showing complete bleaching of intrinsic stains.

Figure 6.

Radiovisiograph showing post endodontic restoration.

Figure 7.

Photograph showing 18 months follow up.

Discussion

Trauma-induced internal pulp bleeding may cause dissemination of blood components into the dentinal tubules, which may cause discoloration of tooth [4]. Then blood degradation products such as haemosiderin, haemin, haematin and haematoidin release iron during hemolysis [5]. The iron can be converted to black ferric sulfide with hydrogen sulfide produced by bacteria, which causes staining of the tooth.

Non-vital bleaching is the minimally invasive procedure for esthetic rehabilitation of discolored non vital teeth. The most common bleaching agents generally fall into two groups: chlorine and its related compounds like sodium hypochlorite and the per-oxygen bleaching agents like hydrogen peroxide or sodium perborate[6]. Anitua et al reported a 100% success rate using the combination of sodium perborate with hydrogen peroxide. [7]. Hence we have used a mixture of 30% hydrogen peroxide in conjunction with sodium perborate.

Spasser first described the bleaching technique in which he inserted a paste of sodium perborate and water into the access cavity [8]. This technique was modified by Nutting and Poe when they replaced water with hydrogen peroxide in 1963 [9]. The effect of different concentration of carbamide peroxide was studied by Yui in 2008 [10]. He concluded that sodium perborate associated with both 10% and 35% carbamide peroxide was more effective than when associated with distilled water.

Glass ionomer cement was used as the barrier material. The shape of the barrier was kept as ‘bobsled tunnel’ when viewed from facial aspect. The significance of this shape is that it blocks all the dentinal tubules which run from pulp chamber to external tooth surface apical to the level of epithelial attachment so that the bleaching agent stays within the cavity and hence prevents external root resorption [11].

External cervical resorption is a serious complication that can occur after internal bleaching [12]. It is usually asymptomatic and detected through routine radiographic examination [13]. Heithersay et al analyzed 257 teeth with cervical resorptions and found that in 3.9% of teeth, it was due to intracoronal bleaching [14]. Attin et al in their review article summed up all the clinical studies and case reports showing cervical resorption after internal bleaching procedure as given in underlying table I which reveals that patients who had bleaching therapy at a young age often have external resorption. A possible explanation is that hydrogen peroxide can more easily penetrate into the periodontium because of wide dentinal tubules in young teeth. [15].

Table I.

Occurrence of cervical resorption after internal bleaching procedures.

| References | Number of bleached teeth | Whitening treatment | Cases of cervical resorption | Age of patients (years) | Cervical seal | Trauma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical studies | |||||||

| Abou-Rass (1998) | 112 | wbt: sp.+30%H2O2 | None | - | - | - | - |

| Anitua et al. (1990) | 258 | wbt: sp.+110 vol H2O2 | None | - | - | - | - |

| Aldecoa & Mayordomo (1992) | |||||||

| Friedman et al. (1988) | 58 | (a) thermocatalytic: 30%H2O2 | 1 | 24 | No | No | Yes |

| (b) wbt 30%H2O2 | 1 | 18 | No | No | No | ||

| (c) thermocat. + wbt 30%H2O2 | 2 | 14 | No | No | Yes | ||

| Heithersay et al. (1994) | 204 | Thermocatalytic: 30%H2O2 | 4 | 1: 10–15 | No | Yes | Yes |

| Following wbt 30%H2O2 | 3: 16–20 | No | Yes | Yes | |||

| Holmstrup et al. (1998) | 69 | wbt: sp. + water | None | ? | Yes | Predominantly | No |

| Case Reports | |||||||

| Al-Nazhan (1991) | 1 | Thermocatalytic: 30%H2O2 | 1 | 27 | No | No | Yes |

| Following wbt: sp. + 30%H2O2 | |||||||

| Cvek & Lindvall (1985) | 11 | Thermocatalytic: 30%H2O2 | 11 | <21 | No | Yes: 10 | Yes |

| Following wbt 30%H2O2 | No: 1 | ||||||

| Friedman (1989) | 3 | No exact description | 3 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Gimlin & Schindler (1990) | 1 | wbt: sp.+30%H2O2 | 1 | 13 | No | Yes | No |

| Goon et al. (1986) | 1 | wbt: sp.+30%H2O2 | 1 | 15 | No | Yes | No |

| Harrington & Natkin (1979) | 7 | Thermocatalytic: 30%H2O2 | |||||

| Following wbt: sp. + 30%H2O2 | 7 | 14–29 | No | Yes | Yes | ||

| Lado et al. (1983) | 1 | Thermocatalytic: 30%H2O2 | 1 | 44 | No | No | Yes |

| Following wbt: sp. + 30%H2O2 | |||||||

| Latcham (1986) | 1 | wbt: Endoperox | 1 | 8 | No | Yes | No |

| Latcham (1991) | 1 | wbt: Endoperox | 1 | 14 | No | Yes | No |

| Montgomery (1984) | 1 | No exact description | 1 | 19 | ? | Yes | ? |

The age of patients means the age at the time of the whitening treatment. The columns cervical seal, occurrence of trauma and application of heat refer to teeth witch showed cervical resorption.

?: No statement; sp. sodium perborate; wbt: walking bleach technique.

The reason for resorption of bleached teeth have not yet been successfully understood. It has been established that 30% hydrogen peroxide alone or in combination with sodium perborate are more cytotoxic for periodontal cells than perborate-water mixture [16]. Lado et al presumed that internal bleaching procedure leads to denaturation of dentin in the cervical region. This denatured dentin induces a foreign body reaction [17].

It is established that hydrogen peroxide has an effect on both organic as well as inorganic part of dentin. Destruction of organic component is mainly due to the oxidizing nature of hydrogen peroxide, whereas the inorganic portion is damaged due to acidity [18]. Heat application causes widening of dentinal tubules which may facilitate easier diffusion of HYDROGEN PEROXIDE to the periodontium [19]. Application of heat also results in formation of extremely reactive hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide which can degrade the connective tissue. Hence, we have refrained from heat activation of sodium perborate- hydrogen peroxide mixture in the presented case to avoid any possible complications. Montgomery showed that intra-coronal dressing can prevent progression of external cervical resorption [20]. Cervical resorption can be treated by direct restoration after gaining access via orthodontic extrusion or surgical way. Hence a barrier using glass ionomer cement was placed in a bobsled tunnel design to prevent resorption.

Conclusion

Non-vital bleaching is economical, predictable and rather quick with good esthetic result. However, it depends on the endodontist’s expertise to proceed ahead with a good case selection and to prevent any post procedural problems that may occur.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge Dr. Vinod Bhandari, Chairman and Dr. Manjushree Bhandari, Chairperson, SAIMS, for their guidance in preparation of manuscript.

References

- 1.Watts A, Addy M. Tooth discolouration and staining: a review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2001;190(6):309–316. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wray A, Welbury R Faculty of Dental Surgery, Royal College of Surgeons. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: Treatment of intrinsic discoloration in permanent anterior teeth in children and adolescents. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2001;11(4):309–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2001.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey CM. Tooth whitening: what we now know. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14( Suppl):70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arens D. The role of bleaching in esthetics. Dent Clin North Am. 1989;33(2):319–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guldener PHA, Langeland K. Endodontologie. 3rd ed. Stuttgard: Thieme; 1993. pp. 39–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farr JP, Smith WL, Steichen DS. Bleaching Agents. Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. 20032000:1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anitua E, Zabalegui B, Gil J, Gascon F. Internal bleaching of severe tetracycline discolorations: four-year clinical evaluation. Quintessence Int. 1990;21(10):783–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spasser HF. A simple bleaching technique using sodium perborate. NYS Dent J. 1961;27(8–9):332–334. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nutting EB, Poe GS. A new combination for bleaching teeth. J So Calif Dent Assoc. 1963;31(9):289–291. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yui KC, Rodrigues JR, Mancini MN, Balducci I, Gonçalves SE. Ex vivo evaluation of the effectiveness of bleaching agents on the shade alteration of blood-stained teeth. Int Endod J. 2008;41:485–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner DR, West JD. A method to determine the location and shape of an intracoronal bleach barrier. J Endod. 1994;20(6):304–306. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)80822-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacIsaac AM, Hoen CM. Intracoronal bleaching: concerns and considerations. J Can Dent Assoc. 1994;60(1):57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trope M. Cervical root resorption. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128( Suppl):56S–59S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1997.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heithersays GS, Dahlstrom SW, Marin PD. Incidence of invasive cervical resorption in bleached root-filled teeth. Aust Dent J. 1994;39(2):82–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1994.tb01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attin T, Paqué F, Ajam F, Lennon AM. Review of the current status of tooth whitening with the walking bleach technique. Int Endod J. 2003;36(5):313–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinomoto Y, Carnes DL, Ebisu S. Cytotoxicity of intracanal bleaching agents on periodontal ligament cells in vitro. J Endod. 2001;27(9):574–577. doi: 10.1097/00004770-200109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lado EA, Stanley HR, Weisman MI. Cervical resorption in bleached teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55(1):78–80. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(83)90310-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang T, Ma X, Wang Y, Zhu Z, Tong H, Hu J. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on human dentin structure. J Dent Res. 2007;86(11):1040–1045. doi: 10.1177/154405910708601104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotstein I, Torek Y, Lewinstein I. Effect of bleaching time and temperature on the radicular penetration of hydrogen peroxide. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1991;7(5):196–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1991.tb00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery S. External cervical resorption after bleaching a pulpless tooth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;57(2):203–206. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]