Abstract

Understanding culture as a means of preventing or treating health concerns is growing in popularity among social behavioral health scientists. Language is one component of culture and therefore may be a means to improve health among Indigenous populations. This study explores language as a unique aspect of culture through its relationship to other demographic and cultural variables. Participants (n = 218) were adults who self-identified as American Indian, had a type 2 diabetes diagnosis, and were drawn from two Ojibwe communities using health clinic records. We used chi-squared tests to compare language proficiency by demographic groups and ANOVA tests to examine relationships between language and culture. A higher proportion of those living on reservation lands could use the Ojibwe language, and fluent speakers were most notably sixty-five years of age and older. Regarding culture, those with greater participation and value belief in cultural activities reported greater language proficiency.

Keywords: Indigenous, American Indian, language, culture

Ojibwe people call themselves “Anishinaabe,” which has been given various meanings by historians and linguists. Contextually, “Anishinaabe” can mean American Indian or, more specifically, Ojibwe. Most importantly, the term “Anishinaabe” unites people and, for our purposes, unites Indigenous people in the struggle and persistence to revitalize Indigenous languages and Indigenous culture for the health of all human beings.

Indigenous people make up roughly 5 percent of the world’s population. They speak thousands of different languages in over seventy different countries (United Nations Secretariat 2009). Traditional activities within and across Indigenous nations vary significantly. It could be argued that many of these activities, although different, are embedded in similar cultural value systems. Health-based researchers have studied and are studying the connection between culture and improved health (Rowan et al. 2014), yet we have not fully explored how language fits into the broader umbrella of cultural values and activities—an important undertaking that can direct efforts to promote cultural and language revitalization efforts. This paper explores the connection between Indigenous language proficiency, participation in traditional and spiritual activities, and cultural values within two Anishinaabeg communities representing a shared cultural group in the United States.

Ojibwe People

Based on the 2010 U.S. census, there are over 5.2 million people who self-identify as American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) (U.S. Census Bureau 2012). Of these people, 170,742 self-identify as Ojibwe, which is the fifth largest AI tribal grouping in the United States. Ojibwe people reside in urban, rural, and reservations settings across the United States and Canada. In the United States, Ojibwe communities make up over a dozen smaller reservations owing to various treaty negotiations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that depleted land-bases and defined reservation boundaries (Treuer 2010). While Ojibwe reservations are small in comparison to other tribal territories, Ojibwe reservations span a large geographical region that includes North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and southern Canada.

Although the Ojibwe language is considered severely endangered, as are many Indigenous languages (Moseley 2010), it is also considered capable of revitalization based on the number of first- and second-language speakers (Norris and MacCon 2003). With more than eight thousand speakers, over half (61%) of whom live outside of AI/AN reservations, Ojibwe ranks ninth in the number of Indigenous speakers in the United States (Siebens and Julian 2011). While the census gives details on speakers by age and percentage of Indigenous language spoken in the home, information on Ojibwe speakers is limited because statistics are combined for all Indigenous languages in the United States, obscuring different historical and contemporary circumstances.

Indigenous Language Revitalization

Indigenous people across the globe are revitalizing their native languages. The Maori of New Zealand and Native Hawaiians have paved the way for language revitalization efforts, modeling abilities to improve endangered language when most first-language speakers have passed on. Communities in the Southwest United States have maintained a great deal of their first-language speakers but continue to support efforts to preserve language proficiency among the younger generations. Language revitalization efforts are receiving growing attention within Ojibwe communities, as well, as language immersion primary education programs, adult language nests, and local public policy declaring Ojibwe as the official language of tribes emerge (Gunderson 2010; Hermes, Bang, and Marin 2012; Fahrlander 2015). Community members and linguists alike share in the urgency and importance of revitalizing languages and preserving local dialects, especially because time with elders—overwhelmingly the first-language speakers—is uncertain.

The Importance of Indigenous Languages

Language is important to community operation and therefore to community well-being. Language transmits ideas, beliefs, and knowledge, thereby enhancing social support, interpersonal relationships, and shared identity (Chandler and Lalonde 1998). Speaking and understanding one’s Indigenous language has more significance than communication alone. Indigenous languages preserve important concepts and epistemologies that shape entire belief systems, and they define how people formulate ideas and make decisions (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996; Crawford 1995; Norris 2004). Some scholars stress that less variety in languages equates to less variety in ideas, stifling personal and political progress (Crawford 1995).

Songs, prayers, and ceremonial activities are often delivered strictly in the Indigenous language. Therefore, language preservation is critical to communication between generations, communication with the spirit world, and the transmission of teachings (concepts, symbolism, oral stories) within cultural, spiritual, and religious practices. Language use within these practices affects the identity, culture, and health of Indigenous populations (King, Smith, and Gracey 2009). Without language, the intergenerational transmission of values and belief systems would be obstructed (Indigenous Language Institute 2002), affecting the health of our future generations.

Indigenous Languages and Health

Researchers have looked increasingly to culture to improve health behaviors, compiling more evidence that culture may prevent and treat health outcomes such as depression and substance abuse (Walters, Simoni, and Evans-Campbell 2002; Stone et al. 2006; Rieckmann, Wadsworth, and Deyhle 2004). How we use and define culture in studies varies—from cultural activities to cultural values to cultural symbols. Language is sometimes but not always used, and rarely is it considered as a separate construct.

Despite community emphasis on language revitalization, there is limited research highlighting Indigenous languages as a separate and distinct concept from culture. Within the available literature, discrepancies exist that fail to explain the full effect of language on health. The 2008 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey reported that Aboriginal youth aged fifteen to twenty-four years who spoke an Indigenous language were less likely to consume alcohol at risky levels or to have used illicit substances in the previous twelve months (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2012). Hodge and Nandy (2011) reported that significantly greater percentages of individuals with the ability to speak their tribal language were in the “good wellness” group versus the “poor wellness” group, with “wellness” defined as feeling good and taking care of oneself physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually (17% vs. 29%). Two reports found positive relationships between language and health in Indigenous communities in Canada by measuring community-wide language preservation and community-wide measures of health behaviors. Hallett, Chandler, and Lalonde (2007) found that tribal groups with lower levels of language knowledge had six times more youth suicides than those with higher language knowledge. The study also measured other factors related to what Chandler and Lalonde (1998) consider cultural continuity factors, which determine whether a group of people maintains control over their communities. For the tribal groups that had all other cultural continuity factors, language still decreased youth suicide by almost 50 percent. Similarly, Oster and colleagues (2014) found that higher Indigenous language knowledge rates predicted lower prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes, even after adjusting for socioeconomic factors.

Whereas these statistics are promising, other studies have found negative relationships between Indigenous languages and health. A cross-sectional survey of Indigenous people of Australia found that speaking and understanding an Indigenous language and having an Indigenous language as the main language spoken in the home was associated with increased sadness (Biddle and Swee 2012). Similarly, in Canada, Indigenous language was negatively associated with community well-being. Community well-being was defined through community level education, labor force, income, and housing conditions (Capone, Spence, and White 2013). Indigenous-only language use in the home has also been associated with decreased access to health care (Bird et al. 2008; Hahm et. al. 2008; Schumacher et al. 2008).

If taken literally, these results might discourage revitalization attempts. However, there are numerous contextual factors to consider when interpreting results. Communities with high language preservation often are also isolated geographically, which is how they maintain Indigenous language use because they are less affected by assimilation. Geographical isolation is associated with poverty, poor housing, less educational opportunity, and less economic opportunity. These factors could also lead to sadness and diminished community well-being as defined by one study (Capone, Spence, and White 2013). Changing the way we define well-being impacts the interpretation of results. Having community members define well- being prior to using well-being as an outcome would be more meaningful. Geographic isolation combined with immersion in Indigenous languages may also hinder an individual’s ability to speak the dominant language, an inability that has been shown to decrease access to health care and increase racial discrimination in other minority populations (Gee and Ponce 2010). Decreased access to health care and increased racial discrimination, especially in health-care settings, would impact health and well-being as it pertains to receiving routine check ups and specialty services. Individuals that use and learn their Indigenous language may also immerse themselves in traditional culture and find less meaning in Western education and Western economy (Capone, Spence, and White 2013). Straying from these societal norms would affect education, employment, and income—all factors measured by the community well-being score.

Measuring Language and Culture

Few researchers focus on Indigenous language as a separate concept from culture with unique qualities that may not only affect health outcomes but may also enhance the effects of other cultural variables (identity, traditional activities, beliefs, etc.) on health. Several researchers have found a positive relationship between cultural factors and improved mental health. These cultural factors had some similarities but often vary in definition. Participation in cultural activities included traditional food customs, traditional forms of socialization, and traditional forms of art (Whitbeck et al. 2002; LaFromboise et al. 2006; Kading et al. 2015). Cultural identity varied considerably. While some followed Oetting and Beauvais’s (1990–1991) American Indian Cultural Identification Scale, which left the definition of identity open to the respondent (Whitbeck et al. 2002; LaFromboise et al. 2006), others modified or created their own scale based on community- specific definitions (Moran et al. 1999; Rieckmann, Wadsworth, and Deyhle 2004). Asking respondents whether they follow a specified way of life was also used to define enculturation or acculturation (Wolsko et al. 2007). Others (Moran et al. 1999; LaFromboise et al. 2006; Whitesell et al. 2014) incorporated language in their culture-based scales of cultural engagement, ethnic identity, and enculturation. Therefore, it is difficult from these studies to predict the relationship between language and health outcomes.

Often, researchers assume language is built into cultural frameworks of health, minimizing the focus on the direct benefits of language use on health outcomes. Language is considered simultaneously with other measures of culture, as demonstrated in the lack of language-specific health research. Certainly, culture and language interact in ways that make it hard to differentiate the unique health benefits. Participants of one qualitative study describe Indigenous language as a critical and inseparable aspect of culture without which Indigenous people would be incapable of surviving because it is the foundation by which people collectively live and practice culture (Oster et al. 2014).

Given contradictions in the literature, this study intends to more clearly delineate the relationship between language, demographic variables, and other cultural variables in a study of Ojibwe adults. For both community members and researchers, this study advances our theoretical understanding of these constructs to better utilize community assets to improve the health and well-being of the people.

Method

The data for this paper are from the larger community-based participatory research study Mino Giizhigad (Ojibwe for “A Good Day”) that examined how mental health factors relate to diabetes treatment and outcomes for American Indian adults with type 2 diabetes (Walls et al. 2014). The Mino Giizhigad study included participants from two Ojibwe communities— the Lac Courte Oreilles and Bois Forte Bands of Chippewa.1 The Mino Giizhigad study was approved by the Indian Health Service and the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Boards; tribal resolutions were also obtained prior to funding submission. Both tribes actively partnered with researchers from the University of Minnesota Medical School for this project, with regular meetings of the respective tribal Community Research Councils.

Study Participants

Potential participants were identified from health clinic records from each tribal clinic. Eligibility criteria included (a) being 18 years of age or older, (b) self-identifying as American Indian, and (c) having a type 2 diabetes diagnosis. Probability sampling was used to randomly select patients from each reservation clinic who met these inclusion criteria. Of the 289 identified and eligible individuals, 75 percent (n = 218) consented to participate in the study and completed the self-report and interview-administered measures described below. Participants were given $30 and a pound of local wild rice for their time and effort. Further procedural details are provided in Walls and colleagues (2014).

Measures

Demographics

We asked participants to provide their age as a continuous variable, gender (male = 0, female = 1), and educational attainment (“less than high school,” “high school or GED,” “some college, vocational or technical training,” “college graduate,” or “advanced degree”). We collapsed educational attainment into two groups (high school or less, and some college or more). Annual household income was reported in $10,000 ranges, and the midpoint of this range divided by the number of people living in the household was used to calculate the per capita income. Additionally, the federal poverty calculation was used to categorize participants as above or below the federal poverty level. We also asked if participants currently live on reservation land, or if they had lived on reservation land prior to age eighteen.

Language

We categorized Ojibwe language understanding and speaking proficiency based upon self-report from four questions. Understanding Ojibwe was determined by asking participants if they could understand any spoken Ojibwe, and if so, whether they could easily understand spoken Ojibwe. We categorized participants’ understanding based on responses, provided by the survey, as “None” (0), “Any” (1), and “Easily” (2). Speaking Ojibwe language was assessed by asking participants if they could speak some Ojibwe language, and for those that could, if they could speak fluently. We categorized individuals’ speaking proficiency as “None” (0), “Some” (1), and “Fluent (2).

Culture

We queried several elements of Ojibwe cultural participation and values. Participation in traditional activities was measured with a seventeen-item traditional activities index (Whitbeck et al. 2004). Participants were asked if they had participated in each activity within the past twelve months, with either a “Yes” (1) or “No” (0) response, resulting in a sum total with a range from zero to seventeen. Example scale items included “done any beading,” “gone ricing,” and “listened to elders tell stories.” The traditional activities index had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.811. Participation in traditional spiritual activities was measured with a nine-item spiritual activity index (Whitbeck et al. 2004) with similar prompt and response categories. The resultant scale had scores ranging from zero to nine, and included items such as “offered tobacco,” “gone to ceremonial feasts,” and “sought advice from a spiritual advisor.” The spiritual activities index had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.791.

We asked how much the participant’s family does special things together that are based on Ojibwe culture, how much his or her family lives by or follows Ojibwe ways, and how much he or she lives by or follows Ojibwe ways. Response options for these questions were “A lot,” “Some,” “Not much,” and “None.” We collapsed “A lot” and “Some” into one category, and “Not much” and “None” into another category. We also asked how important traditional spiritual values are to the way participants lead their lives, with response categories of “Very important,” “Somewhat important,” “Not too important,” and “Not at all important.” We collapsed responses into “Very important” and all others.

Analysis

We used SPSS (Version 20) for data analysis. Chi-square tests were used to examine differences between categories of language proficiency and several demographic characteristics. We used chi-square tests to compare language proficiency by nominal groups, and ANOVA tests, with Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons, to examine relationships between language and traditional and spiritual activities.

Results

Descriptive analyses revealed the mean age of participants in this study was 56.5 years (31.7% were aged 65 years or older), and the mean annual per capita income was $10,331, 44.4 percent falling below the federal poverty limit. Over half of the sample was female (56.4%) and had completed some college or higher (60.4%). Most had lived on reservation lands prior to age eighteen (80.7%), and 77.5 percent now lived on reservation lands.

Regarding understanding spoken Ojibwe, 76 (34.9%) of the participants in this study could easily understand, 93 (42.7%) could understand some, and 49 (22.5%) could not understand any. Concerning speaking Ojibwe, 14 (6.4%) reported being able to speak fluently, 138 (63.3%) could speak some, and 66 (30.3%) could not speak any.

Tables 1 and 2 show the percent of participants understanding and speaking Ojibwe by demographic group. The proportion of respondents that understand any or easily understand spoken Ojibwe was significantly higher among people currently living on reservation lands (p = 0.019) and those who lived on reservation land before age eighteen (p = 0.005). The proportion speaking Ojibwe fluently was higher among individuals sixty-five years or older (p = 0.003) compared to those younger than sixty-five, and significantly more of those speaking some or fluent Ojibwe currently lived on reservation lands (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Percent understanding proficiency by demographic categories

| Percent Understanding | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Any | Easy | ||

| Total | 23% | 43% | 35% | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 24% | 48% | 36% | 0.212 |

| Female | 21% | 39% | 40% | |

| Age | ||||

| Less than 65 years | 25% | 44% | 31% | 0.165 |

| 65 years or older | 17% | 29% | 43% | |

| Currently live on reservation lands | ||||

| No | 37% | 31% | 33% | 0.019 |

| Yes | 18% | 46% | 36% | |

| Lived on reservation lands before 18 | ||||

| No | 41% | 38% | 21% | 0.005 |

| Yes | 18% | 44% | 38% | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| High school or less | 22% | 35% | 43% | 0.095 |

| Some college or above | 22% | 48% | 30% | |

| Household income | ||||

| Below federal poverty limit | 22% | 39% | 40% | 0.466 |

| Above federal poverty limit | 23% | 45% | 32% | |

Table 2.

Percent speaking proficiency by demographic categories

| Percent Speaking | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Some | Fluent | ||

| Total | 30% | 63% | 6% | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 34% | 61% | 5% | 0.567 |

| Female | 28% | 65% | 7% | |

| Age | ||||

| Less than 65 years | 33% | 64% | 3% | 0.003 |

| 65 years or older | 25% | 61% | 15% | |

| Currently live on reservation lands | ||||

| No | 53% | 41% | 6% | 0.000 |

| Yes | 24% | 70% | 7% | |

| Lived on reservation lands before 18 | ||||

| No | 41% | 57% | 2% | 0.181 |

| Yes | 28% | 65% | 7% | |

| Educational attainment | ||||

| High school or less | 33% | 57% | 11% | 0.088 |

| Some college or above | 28% | 68% | 4% | |

| Household income | ||||

| Below federal poverty limit | 29% | 62% | 9% | 0.301 |

| Above federal poverty limit | 32% | 64% | 4% | |

ANOVA tests showed differences in mean number of traditional activities (p = 0.001; p = 0.006) and spiritual activities (p < 0.001; p < 0.001) across Ojibwe understanding and speaking categories, respectively. After applying the Bonferroni correction to p values, we saw significant differences between low and high Ojibwe proficiency, as shown in figures 1 and 2. Overall, higher proficiency in both understanding and speaking was related to higher reports of traditional and spiritual activities.

Figure 1. Mean traditional activities by Ojibwe proficiency category.

ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction; * Significantly different than “No” and “Any” understanding groups; ** Significantly different than “No” speaking group

Figure 2. Mean spiritual activities by Ojibwe proficiency category.

ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction; *Significantly different than “No” understanding group; **Significantly different than “No” and “Some” understanding groups; *** Significantly different than “No” speaking group

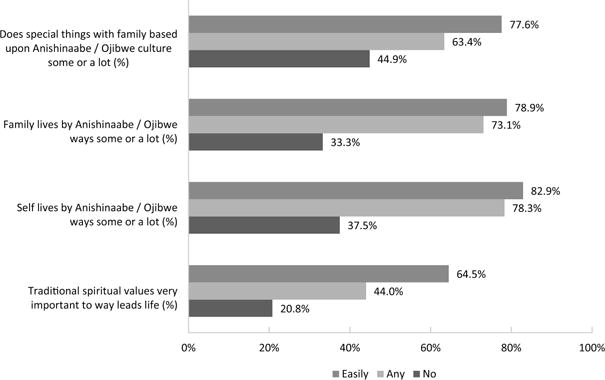

Of all participants in this study, 64.2 percent reported doing some or a lot of special things with their family based on Ojibwe culture. The majority of participants (66.4%) reported that their family lives by or follows Ojibwe ways some or a lot, and 70.8 percent felt that they lived by or followed Ojibwe ways some or a lot. Nearly half (46%) reported that traditional spiritual values are very important to the way they lead their lives. Comparisons of these variables by Ojibwe language proficiency groups are illustrated in figures 3 and 4. Significant differences were found between proficiency, both understanding and speaking, for all of these culturally salient variables. The clear trend here is that those understanding easily and speaking proficiently have the highest percent affirming these four culturally salient items.

Figure 3.

Percent within understanding proficiency category

Figure 4.

Percent within speaking proficiency category

Discussion

In this study, we examined Ojibwe language proficiency and its relationship to cultural variables in a sample of 218 Ojibwe adults with type 2 diabetes living in the northern Midwest United States. Thirty-five percent could easily understand the language, and six percent were fluent. Greater language proficiency was associated with living on the reservation (now as well as before age eighteen) and being older than sixty-five years of age. Language proficiency was associated with more participation in traditional and spiritual activities, as well as endorsing and living by traditional spiritual values. These findings highlight and further delineate the strong connection between Indigenous language and cultural values and participation, and they provide the basis for future investigations considering the relationship between language, cultural involvement, and health.

Results indicated individuals currently living on the reservation spoke and understood the language more than those who lived outside the reservation. This distinction is particularly of note given that individuals in this study were recruited based on their use of a tribal health clinic. In other words, even those that did not live on reservation lands lived close enough to access tribal health services on tribal lands. Living on the reservation connects community members with cultural opportunities not afforded to many off-reservation residents. The distance from reservation cultural and community assets (i.e., attendance at nontribal schools) may decrease the likelihood of language involvement enough to lead to a negative correlation between living off the reservation and language proficiency. Cultural activities, as we have also found in this study, were related to proficiency in the language.

We found that understanding the language was associated with living on the reservation before the age of eighteen; however, speaking the language was not associated. This result matches with how people develop language. People tend to understand a language before they are able to produce it, much like an infant. In that respect, if one grew up in the language, which might be linked to living on the reservation before the age of eighteen, and then moved away, it is likely that one would understand some but produce less.

Being a fluent speaker was associated with being aged sixty-five years or more. This fits with UNESCO’s Language Vitality and Endangerment framework, in which the most significant factor is intergenerational language transmission. Languages are termed more endangered as the younger generations stop using the language. It is most common in Indigenous communities that the first-language speakers and fluent speakers are elders. In a report from the 2006–2010 American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey, older people reported speaking their Indigenous language in the home at a much higher rate than the young people (11% of 15- to 17-year-olds vs. 22.3% of 65+ year-olds) (Siebens and Julian 2011).

We measured culture by asking about participation in the last year in specific traditional activities such as spearfishing, making blankets, and listening to elder stories, but we also asked more general questions that allowed the participants to self-identify what Ojibwe culture meant to them. We asked about following life standards and living by traditional life ways. In both specific and broad ways of wording the questions, we found that culture was associated with proficiency in the language. This finding strengthens anecdotal literature that maintains that culture cannot exist without language and vice versa (McIvor, Napoleon, and Dickey 2009).

Similar to the findings with traditional activities, participating in spiritual activities and considering spiritual values important were both associated with greater language proficiency. Language is a critical aspect of traditional spiritual activities. While many spiritual advisors and ceremonial leaders provide interpretation for those they are helping, much of the spiritual meaning is lost because concepts do not always translate into the dominant culture’s language. Because of this, greater language knowledge may facilitate participation in traditional spiritual activities. On the other hand, participation in spiritual activities conducted in the language may lead to greater language acquisition, or an increased interest in learning the language.

Both spiritual and cultural activities have important implications for health and healing, which makes understanding factors associated with participation in these activities especially valuable. For example, participation in traditional spiritual activities has been found to be associated with a lower likelihood of past-year alcohol abuse (Whitbeck et al. 2004), and low enculturation has been found to be a strong predictor of alcohol problems (Currie et al. 2011). Culture has been shown to be connected to positive mental health (Kading et al. 2015), positive psychological well-being (Moran et al. 1999), resiliency factors among adolescents such as positive attitude toward schools and reaching academic goals (LaFromboise et al. 2006), greater happiness, and the use of religion or spirituality (versus substances) to cope with stress (Wolsko et al. 2007). Health benefits of culture and spirituality have always been understood by tribal communities and often requested within treatment programs (Legha and Novins 2012). Recently, scientific studies have also recognized this important relationship.

Limitations

The generalizability of these findings is limited to adults living with diabetes sampled from clinic records. The fact that these adults had at some point sought services at tribal clinics potentially suggests some degree of community involvement or may be an indicator of tribal enrollment or eligibility for IHS services.

Self-report questions were used to measure language, and more thorough or extensive measures would help improve our understanding of language and its relationship to culture and health. Our survey instrument, along with other health-based research methods, underestimates the complexity of Indigenous languages. Using an oral interview would be more sufficient but has its drawbacks as well, especially for endangered languages. The interviewer, even if trained in oral interview methods, must be consistent to make the test reliable across all subjects. The interviewer must also be well versed in the language in order to converse with each subject on contexts relevant to the subject’s life.

Survey questionnaires cannot capture the many contexts in which language is used. Because many individuals do not have the ability to use the Indigenous language to its fullest extent, individuals might not be aware of the complexities of using language within all aspects of life, from everyday conversations with family and peers to classroom use when studying complex mathematical or scientific concepts to sending prayers through spiritual realms.

One strength of this study is that it provided participants with a broad range of questions to dig into spirituality and culture. Participants were asked about their involvement in very specific and locally relevant traditional and spiritual activities. In addition, they were asked questions that allowed them to include their own interpretation of culture and spirituality. We used both types of measurement items within analyses.

There may also be deficits in the way we, as researchers, perceive and measure health. Ideas of community well-being and health can be much different than the dominant culture, and researchers should consider finding new ways to measure positive health variables. For example, while American Indians have disproportionately higher rates of depression when compared to national averages, over half (51.5%) of one study population also experienced flourishing positive mental health (Kading et al. 2015).

Summary and Future Directions

Our findings from Ojibwe community members highlight the strong connection between culture and language proficiency and provide a point estimate of language proficiency among community members. Language and cultural participation are closely connected, and both are seen as key mechanisms for improving health and wellness in Indigenous communities. Because the data were cross-sectional, we do not know if language use facilitates participation in the cultural and spiritual activities, or if these activities encourage the development of the language. Both are likely occurring. Before relying heavily on quantitative research methods to understand language’s role in health, it would be beneficial to first seek qualitative knowledge that deciphers the role language plays in healthy behaviors. In addition, future research should investigate how language knowledge or acquisition may lead to improved health. Our findings suggest that language and cultural involvement complement each other. Language programs that include cultural teachings and cultural involvement may be more successful in language revitalization and language preservation. Because elders were most likely to be fluent, and because a minority of participants could easily speak the language, this study underscores the critical need for language revitalization efforts across Ojibwe communities to tap into the vital resources of our elders.

Biographies

MIIGIS B. GONZALEZ, MPH, Ph.D., is a recent graduate in the Social and Administrative Pharmacy Ph.D. Program and a research assistant in the School of Medicine at the University of Minnesota, Duluth campus. She is an enrolled member of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe. Her research interests include culture, language, and community-based approaches to Indigenous health and wellness with an emphasis on mental health, substance abuse prevention, and adolescent development.

BENJAMIN D. ARONSON, PharmD, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of social and administrative pharmacy at the Ohio Northern University Raabe College of Pharmacy. His research interests include health professional student development, advancing health service access and quality, and improving health care services in underserved communities by understanding health behav-iors and other social and structural determinants of health. Dr. Aronson’s teaching interests include the principles of pharmaceutical care, health care systems, quality in health care, and professional and leadership development of student pharmacists.

SIDNEE KELLAR, community research council member for the Mino Giizhigad study, was born in Washington the day after her dad discharged from the army. After moving to Wisconsin, she lived by her mom’s family’s cranberry marsh and her dad’s reservation. An Ojibwe elder would come over for coffee. He’d ask, “Sid’nee, how do you say horse?” Years later she started working at the tribal college and that same elder was there, teaching Ojibwe. Now his question was, “Sid’nee, when are you going to take my class?” She did, eventually graduating with an interdisciplinary studies degree. She currently teaches high school Ojibwe.

MELISSA L. WALLS, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the Department of Biobehavioral Health and Population Sciences at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus. Dr. Walls is affiliated with the Bois Forte and Couchiching First Nation Anishinaabe. She is a social scientist committed to collaborative research with tribal communities in the United States and Canada. Her involvement in community-based participatory research (CBPR) projects to date includes mental health epidemiology; culturally relevant, family-based substance use prevention and mental health promotion programming and evaluation; and examining the impact of stress and mental health on diabetes.

BRENNA L. GREENFIELD, Ph.D., is a psychologist and assistant professor in the Department of Biobehavioral Health and Population Sciences at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth campus. Her research is strengths-based and focuses on identifying and intervening on determinants of substance use and misuse among Native Americans.

Footnotes

NOTE “Chippewa” has been the legal term used by the federal government in major legal and treaty negotiations and is included in the names of multiple tribes (Satz 1991; Treuer 2010), but many members of this group prefer the terms “Anishinaabe” or “Ojibwe.”

WORKS CITED

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Culture, Heritage and Leisure: Speaking Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages. 2012 Latest issue released 23 July 2012. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4725.0Chapter220Apr 2011.

- Biddle N, Swee H. The Relationship between Wellbeing and Indigenous Land, Language and Culture in Australia. Australian Geographer. 2012;43(3):215–32. doi: 10.1080/00049182.2012.706201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bird SM, Wiles JL, Okalik L, Kilabuk J, Egeland GM. Living with Diabetes on Baffin Island: Inuit Storytellers Share their Experiences. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2008;99:17–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03403734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone K, Spence N, White J. Examining the Association between Aboriginal Language Skills and Well-being in First Nations Communities. Aboriginal Policy Research. 2013;9:57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler MJ, Lalonde C. Cultural Continuity as a Hedge Against Suicide in Canada’s First Nations. Transcultural Psychiatry. 1998;35(2):191–219. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. Endangered Native American Languages: What Is to Be Done, and Why? The Bilingual Research Journal. 1995;19(1):17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Currie CL, Wild TC, Schopflocher DP, Laing L, Veugelers PJ, Parlee B, McKennitt DW. Enculturation and Alcohol Use Problems Among Aboriginal University Students. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 2011;56(12):735–42. doi: 10.1177/070674371105601205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrlander S. Lac Courte Oreilles Tribe Proclaims Ojibwemowin as the Official Language of the Tribe and Reservation. Lac Courte Oreilles News. 2015 http://www.lco-nsn.gov/lac-courte-oreilles-news.php.

- Gee GC, Ponce N. Associations between Racial Discrimination, Limited English Proficiency, and Health-related Quality of Life among 6 Asian Ethnic Groups in California. American Journal of Public Health: Research and Practice. 2010;100(5):888–95. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson D. White Earth Nation Makes Ojibwe its Official Language. Statewide (blog) 2010 Post 10 August 2010 https://blogs.mprnews.org/statewide/2010/08/white_earth_makes_ojibwe_official_language/

- Hahm HC, Lahiff M, Barreto R, Shin S, Chen W. Health Care Disparities and Language Use at Home among Latino, Asian American, and American Indian Adolescents: Findings from the California Health Interview Survey. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett D, Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE. Aboriginal Language Knowledge and Youth Suicide. Cognitive Development. 2007;22:392–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hermes M, Bang M, Marin A. Designing Indigenous Language Revitalization. Harvard Educational Review. 2012;82(3):381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge FS, Nandy K. Predictors of Wellness and American Indians. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(3):791–803. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous Language Institute. Community Voices Coming Together; Notes compiled at the National Indigenous Language Symposium; Albuquerque, NM. 7–10 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kading ML, Hautala DS, Palombi LC, Aronson BD, Smith RC, Walls ML. Flourishing: American Indian Positive Mental Health. Society and Mental Health. 2015;5(3):203–17. doi: 10.1177/2156869315570480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous Health Part 2: The Underlying Causes of the Health Gap. The Lancet. 2009;374:76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise TD, Hoyt DR, Oliver L, Whitbeck LB. Family, Community, School Influences on Resilience among American Indian Adolescents in the Upper Midwest. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;38(8):975–91. [Google Scholar]

- Legha RK, Novins D. The Role of Culture in Substance Abuse Treatment Programs for American Indian and Alaska Native Communities. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(9):686–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIvor O, Napoleon A, Dickie KM. Language and Culture as Protective Factors for At-risk Communities. Journal of Aboriginal Health. 2009;5(1):6–25. [Google Scholar]

- Moran JR, Fleming CM, Somervell P, Manson SM. Measuring Bicultural Ethnic Identity among American Indian Adolescents: A Factor Analytic Study. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14(4):405–26. [Google Scholar]

- Moseley C, editor. UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. 3rd. Paris: UNESCO; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/index.php. [Google Scholar]

- Norris M. From Generation to Generation: Survival and Maintenance of Canada’s Aboriginal Languages within Families, Communities and Cities. TESL Canada Journal. 2004;21(2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Norris M, MacCon K. Aboriginal Language Transmission and Maintenance in Families: Results of an Intergenerational and Gender-based Analysis for Canada, 1996. In: White JP, Maxim PS, Beavon D, editors. Aboriginal conditions: Research as a Foundation for Public Policy. Toronto: UBC Press; 2003. pp. 164–96. [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Orthogonal Cultural Identification Theory: The Cultural Identification of Minority Adolescents. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1990–1991;25(5A & 6A):655–85. doi: 10.3109/10826089109077265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster RT, Grier A, Lightning R, Mayan MJ, Toth EL. Cultural Continuity, Traditional Indigenous Language, and Diabetes in Alberta First Nations: A Mixed Methods Study. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2014;13:92–103. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0092-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieckmann TR, Wadsworth ME, Deyhle D. Cultural Identity, Explanatory Style, and Depression in Navajo Adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10(4):365–82. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan M, Poole N, Shea B, Gone JP, Mykota D, Farag M, Hopkins C, Hall L, Mushquash C, Dell C. Cultural Interventions to Treat Addictions in Indigenous Populations: Findings from a Scoping Study. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2014;9(34):1–26. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. People to People, Nation to Nation: Highlights from the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Minister of Supply and Services; Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Satz RN. Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective. Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters. 1991;79(1):1–251. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Slattery M, Lanier A, Ma K, Edwards S, Ferucci E. Prevalence and Predictors of Cancer Screening among American Indian and Alaska Native People: The EARTH Study. Cancer Causes and Control. 2008;19:725–37. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siebens J, Julian T. Native North American Languages Spoken at Home in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2006–2010. American Community Survey Brief produced for the United States Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stone RA, Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Johnson K, Olson DM. Traditional Practices, Traditional Spirituality, and Alcohol Cessation among American Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(2):236–44. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treuer A. Ojibwe in Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Profile American Facts for Features. Washington, DC: 2012. American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month: November 2012. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb12-ff22.html. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Secretariat. Introduction to State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. New York: United Nations; 2009. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Walls ML, Aronson BD, Soper GV, Johnson-Jennings MD. The Prevalence and Correlates of Mental and Emotional Health among American Indian Adults with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Education. 2014;40(3):319–28. doi: 10.1177/0145721714524282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters KL, Simoni JM, Evans-Campbell T. Substance Use among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Incorporating Culture in an ‘Indigenist’ Stress-Coping Paradigm. Public Health Reports. 2002;117(1):S104–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, McMorris BJ, Hoyt DR, Stubben JD, LaFromboise T. Perceived Discrimination, Traditional Practices, and Depressive Symptoms among American Indians in the Upper Midwest. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43(4):400–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Adams GW. Discrimination, Historical Loss and Enculturation: Culturally Specific Risk and Resiliency Factors for Alcohol Abuse among American Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(4):409–18. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.409. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15376814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell NR, Asdigian NL, Kaufman CE, Crow CBig, Shangreau C, Keane EM, Mousseau AC, Mitchell CM. Trajectories of Substance Use among Young American Indian Adolescents: Patterns and Predictors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:437–53. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolsko C, Lardon C, Mohatt GV, Orr E. Stress, Coping, and Well-being among the Yup’ik of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: The Role of Enculturation and Acculturation. International Journal of Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(1):51–61. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]