Abstract

Purpose

In this multicenter study, we evaluated the cumulative burden of morbidity (CBM) among > 1,200 testicular cancer survivors and applied factor analysis to determine the co-occurrence of adverse health outcomes (AHOs).

Patients and Methods

Participants were ≤ 55 years of age at diagnosis, finished first-line chemotherapy ≥ 1 year previously, completed a comprehensive questionnaire, and underwent physical examination. Treatment data were abstracted from medical records. A CBM score encompassed the number and severity of AHOs, with ordinal logistic regression used to assess associations with exposures. Nonlinear factor analysis and the nonparametric dimensionality evaluation to enumerate contributing traits procedure determined which AHOs co-occurred.

Results

Among 1,214 participants, approximately 20% had a high (15%) or very high/severe (4.1%) CBM score, whereas approximately 80% scored medium (30%) or low/very low (47%). Increased risks of higher scores were associated with four cycles of either ifosfamide, etoposide, and cisplatin (odds ratio [OR], 1.96; 95% CI, 1.04 to 3.71) or bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.98), older attained age (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.26), current disability leave (OR, 3.53; 95% CI, 1.57 to 7.95), less than a college education (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.87), and current or former smoking (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.63). CBM score did not differ after either chemotherapy regimen (P = .36). Asian race (OR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.72) and vigorous exercise (OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.89) were protective. Variable clustering analyses identified six significant AHO clusters (χ2 P < .001): hearing loss/damage, tinnitus (OR, 16.3); hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes (OR, 9.8); neuropathy, pain, Raynaud phenomenon (OR, 5.5); cardiovascular and related conditions (OR, 5.0); thyroid disease, erectile dysfunction (OR, 4.2); and depression/anxiety, hypogonadism (OR, 2.8).

Conclusion

Factors associated with higher CBM may identify testicular cancer survivors in need of closer monitoring. If confirmed, identified AHO clusters could guide the development of survivorship care strategies.

INTRODUCTION

The number of cancer survivors has increased markedly in recent decades, with an estimated 18 million in the United States by 2022.1 Given these increasing numbers, having an understanding and quantifying the late effects of cancer and its treatment to inform survivorship care strategies are important. An important population in which to assess adverse health outcomes (AHOs) are survivors of testicular cancer, the most common cancer in men ages 18 to 39 years.2 Since effective cisplatin-based chemotherapy was introduced in the 1970s,3 the overall age-adjusted 5-year relative survival rate is > 95%,4 and survivors remain at risk for decades for the late effects of cancer and its treatment. Characterization of AHOs is facilitated by the homogeneity of treatment regimens. For four decades, therapy for advanced testicular cancer typically has consisted of platinum-based chemotherapy. For good-risk disease, standard treatment comprises either three cycles of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP × 3) or four cycles of etoposide plus cisplatin (EP × 4), whereas for intermediate- or poor-risk testicular cancer, four cycles of BEP (BEP × 4) or four cycles of etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin (VIP × 4) are administered.5,6 Although treatment of good-risk testicular cancer with BEP × 3 versus EP × 4 results in lower cisplatin exposure, it is accompanied by potential bleomycin adverse effects.7 To our knowledge, no study has evaluated the cumulative burden of morbidity (CBM) after BEP × 4 versus VIP × 4 or after BEP × 3 versus EP × 4 and has taken into account both the number and the severity of AHOs. Such characterization is important to develop risk-stratified, evidence-based follow-up recommendations. Moreover, as noted previously,8 a better understanding of AHOs may help to guide testicular cancer management, especially in the controversial area of whether good-risk patients should receive EP × 4 or BEP × 3.

To provide new information about CBM after contemporary cisplatin-based chemotherapy for testicular cancer, we examined both the number and the severity of AHOs among 1,214 testicular cancer survivors enrolled in the Platinum Study, a large, multicenter clinical investigation.9 We evaluated the co-aggregation of AHOs to identify co-occurring clusters and identified clinical, sociodemographic, and behavioral factors associated with an elevated CBM.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

The Platinum Study was approved by each participating institution’s institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent. The cohort was described in detail previously.2,10 Briefly, eligible testicular cancer survivors had a histologic/serologic diagnosis of germ cell tumor, were age ≤ 55 years at diagnosis, completed first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy ≥ 1 year previously, and were undergoing routine follow-up at the participating site. All participants are referred to as testicular cancer survivors. At study enrollment, participants reported current prescription medication use with indication, underwent a brief physical examination, and completed comprehensive health questionnaires. Cancer diagnosis and treatment data were abstracted from medical records (Appendix, online only). Testicular cancer survivors indicated the average time per week of participating in various physical activities during the past year.11,12 These activities were grouped into vigorous (≥ 6 metabolic equivalent tasks) and nonvigorous (< 6 metabolic equivalent tasks) activities (Appendix).13

Measurement of AHOs

Participant responses were mapped to individual AHOs and graded according to severity on a 0 to 4-point scale using a modified version of the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.03)14 as in prior studies.15,16 A multidisciplinary panel of experts agreed on all grades (C.F., H.D.S., D.M.S., S.D.F., L.H.E., and L.B.T.). Appendix Table A1 (online only) lists individual AHOs and grading criteria.15,16 If no response was provided (< 1%), the AHO was conservatively treated as no symptom/diagnosis. CBM score was calculated on the basis of the number and severity of AHOs by following methods adapted from Geenen et al15 (Appendix Table A2, online only). A secondary CBM score, CBMPt, was calculated using AHOs previously related to cisplatin exposure (ie, peripheral sensory neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, hearing damage, tinnitus, kidney disease).17,18

Statistical Analysis

Discrete and continuous data were described using numbers (percentages) and medians (ranges), respectively. Sociodemographic, health behavior, and treatment variables were individually tested for association with CBM score using t (continuous variables) or Pearson’s χ2 (categorical variables) test. Variables then were combined in a multivariable ordinal logistic regression model, with CBM score as the dependent variable. Unless otherwise noted, variables with Wald χ2 P value ≥ .1 in the full model were removed from the final model. In the latter, the very high and severe CBM categories were collapsed given sparse data. Multivariable models that investigated the effect of cumulative cisplatin dose on CBMPt score included the same covariates as the main model, except that chemotherapy regimen was omitted given its strong correlation with cumulative cisplatin dose.

Ordinal logistic regression examined the relationship between CBM score and self-reported health (the dependent variable). For all ordinal logistic regression models, the assumption of proportionality of odds across response categories was confirmed by comparing the Bayesian information criterion for the proportional odds model to that from a partial proportional odds model. Stata 14.1 software (StataCorp; College Station, TX) was used for all descriptive statistics and regression analyses.

Cluster analysis of variables was performed with nonlinear factor analysis and the nonparametric conditional item-pair covariance method of the cross-validated dimensionality evaluation to enumerate contributing traits procedure (Appendix). Each AHO was dichotomized: grades 0 and 1 were combined, and grades 2, 3, and 4 were combined. Because of sparse numbers, transient ischemic attack and stroke were collapsed into a single AHO; hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia were combined into hyperlipidemia. Average item-pair odds ratios (ORs) were calculated by averaging the log OR across AHO pairs and then by exponentiating the average value.

RESULTS

Median age at evaluation for 1,214 testicular cancer survivors was 37 years (range, 18 to 74 years), and median time since chemotherapy completion was 4.2 years (range, 1 to 30 years; Table 1). Of all participants, 1,157 (95.3%) were seen in the clinic during routine follow-up care, and approximately 90% completed chemotherapy within 15 years of enrollment. Most participants (1,035 [85.3%]) received BEP × 3 (460 [37.9%]), BEP × 4 (222 [18.3%]), or EP × 4 (353 [29.1%]); 44 received VIP, typically four cycles (n = 32). Median cumulative cisplatin dose was 400 mg/m2, with approximately one third receiving 300 mg/m2 (447 [36.8%]). Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was performed in 46.3% of participants. Most survivors were white (85.3%), married/living as married (61.0%), employed (88.7%), and educated beyond high school (88.3%).

Table 1.

Clinical, Sociodemographic, and Health Behavior Characteristics of 1,214 Survivors of Cisplatin-Treated Germ Cell Tumors

The most prevalent AHOs of any severity were obesity (41.7% grade 2, 26.0% grade 3, 3.9% grade 4), sensory neuropathy (28.3% grade 1, 14.5% grade 2, 13.4% grade 3), tinnitus (25.0% grade 1, 7.1% grade 2, 7.5% grade 3), and hearing damage (24.5% grade 1, 13.5% grade 2, 1.2% grade 3; Table 2). Raynaud phenomenon occurred in approximately 33% of participants (15.6% grade 1, 8.7% grade 2, 9.1% grade 3) and pain in approximately 25% (13.6% grade 1, 9.8% grade 2, 1.5% grade 3). Hypogonadism (10.2% grade 2) and erectile dysfunction (15.9% grade 1, 12.5% grade 2) also were observed.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Adverse Health Outcomes By Severity Grade

Figure 1 shows the CBM scores. Approximately 20% of participants had a high (180 [14.8%]), very high (46 [3.8%]), or severe (one [0.1%]) score, whereas 76% had a very low (104 [8.6%]), low (458 [37.7%]), or medium (360 [29.7%]) score. Only 5.4% of participants had no AHOs. All 47 with a very high or severe CBM score had grade 4 obesity.

Fig 1.

Distribution of cumulative burden of morbidity (CBM) score among 1,214 participants in the Platinum Study.

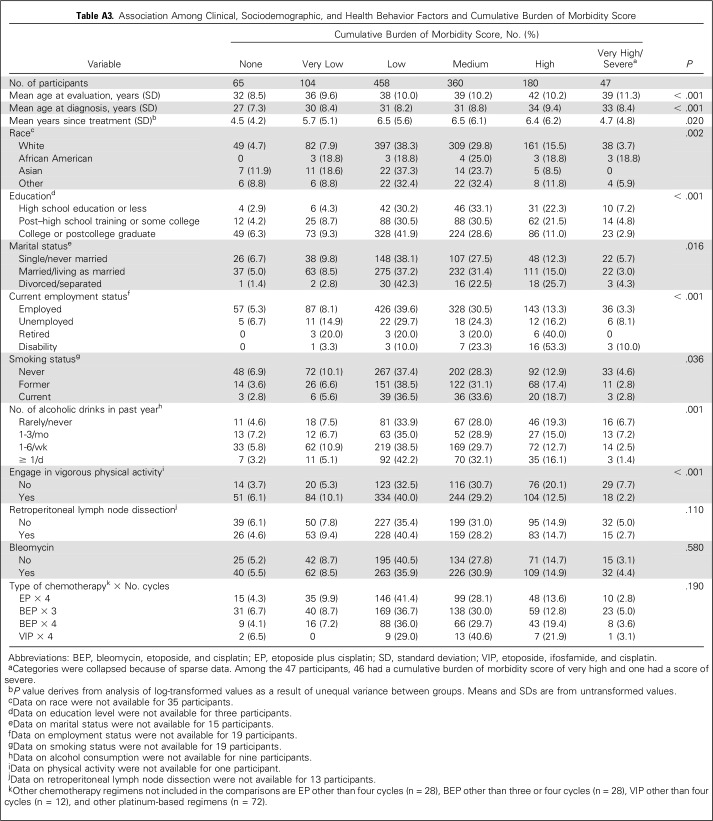

Bivariable associations of clinical, sociodemographic, and health behavior factors with CBM score are shown in Appendix Table A3 (online only). In a multivariable model (Table 3) that controlled for time since chemotherapy and enrollment center, the following were significantly associated with higher CBM score: older attained age (OR, 1.18 per 5 years), BEP × 4 (OR, 1.44 v BEP × 3), VIP × 4 (OR, 1.96 v BEP × 3), less than a college-level education (OR, 1.44), current disability leave (OR, 3.53), and former or current smoking status (OR, 1.28). Although the OR for VIP × 4 was slightly higher than that for BEP × 4, the difference was not significant (P = .36). Disease stage was not associated with CBM score (P = .48), which suggests that increased scores after BEP × 4 or VIP × 4 were not explained by more-advanced tumor status. CBM scores after EP × 4 and BEP × 3 were similar (P = .65). No significant differences were observed for individual AHOs except Raynaud phenomenon (P < .001), for which prevalence and severity after BEP × 3 (183 [39.8%]: 18.5% grade 1, 10.4% grade 2, 10.9% grade 3) exceeded EP × 4 (84 [23.8%]: 12.2% grade 1, 16.8% grade 2, 4.8% grade 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Ordinal Logistic Regression of Factors Associated With Cumulative Burden of Morbidity Score

Asian race (OR, 0.41) and vigorous exercise (OR, 0.68) were inversely associated with higher CBM score. Lower risk in Asian testicular cancer survivors reflects that fewer participants had higher severity grades for 15 of 22 AHOs versus white survivors (eg, peripheral sensory neuropathy: 8.5% v 13.5% grade 3; hearing loss: 8.5% v 14.1% grade 2, 0% v 1.2% grade 3). Similar trends were observed for autonomic neuropathy, tinnitus, Raynaud phenomenon, pain, kidney disease, hypertension, coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease, obesity, thyroid disease, depression/anxiety, erectile dysfunction, and hypogonadism.

The relationship between cumulative cisplatin dose and overall CBM score was of borderline significance (OR per 100 mg/m2, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.37; P = .064) in the multivariable model. However, when limited to conditions previously attributed to cisplatin,14,15 each 100 mg/m2 increase in cumulative dose was associated with significantly worse CBMPt (OR per 100 mg/m2, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.58; P < .001).

Increasing CBM score was significantly associated with worse self-reported health. Compared with testicular cancer survivors with a score of 0, the risk of worse self-reported health among those scored as very low, low, medium, high, or very high/severe was 1.94 (95% CI, 1.08 to 3.48), 2.82 (95% CI, 1.72 to 4.62), 5.91 (95% CI, 3.56 to 9.81), 10.90 (95% CI, 6.28 to 18.93), and 34.17 (95% CI, 16.54 to 70.62), respectively.

Results from both variable clustering methods converged in the analysis of AHOs to yield six major groups of signs/symptoms (χ2 for model fit, P < .001), with pairwise ORs for given clusters as follows: hearing loss/damage, tinnitus (OR, 16.3); metabolic disorders (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia; OR, 9.8); neuropathy and related conditions (sensory neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy, pain, Raynaud phenomenon; OR, 5.5); cardiovascular disease (CVD) and related conditions (coronary artery disease, stroke, kidney disease, peripheral artery disease, thromboembolism, obesity; OR, 5.0); erectile dysfunction, thyroid disease (OR, 4.2); and hypogonadism, depression/anxiety (OR, 2.8). Clusters hearing loss/damage, tinnitus and neuropathy and related conditions, although distinct, were strongly correlated (r = 0.658; P < .001), as were clusters erectile dysfunction, thyroid disease and hypogonadism, depression/anxiety (r = 0.914; P < .001).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the results are based on the largest study to date in testicular cancer survivors administered contemporary cisplatin-based chemotherapy. We characterize the CBM by showing that even at a young age, approximately one in five patients has a score of high to severe, with only 5% reporting no AHOs. Although CBM was higher in participants treated with BEP × 4 or VIP × 4 (v BEP × 3), scores did not differ significantly between the two regimens (P = .36). CBM score also did not differ between BEP × 3 and EP × 4, the standard approaches for good-risk disease. The higher prevalence and severity of Raynaud phenomenon after BEP × 3 is consistent with the known relationship with bleomycin,7 although Raynaud phenomenon also may be related to cisplatin.19 Increasing cumulative cisplatin dose significantly increased risk for a higher CBM score for AHOs related to neuropathy, ototoxicity, and kidney disease. The strong association between higher CBM score and worse self-reported health indicates that the score reflects a health status perceptible to patients. These and other new findings are discussed next.

Previous US investigations of testicular cancer survivors2,20-24 have been limited in scope, generally by either not addressing AHOs21,23,24 or evaluating fewer than five conditions22 (Appendix Table A4, online only). Although three studies obtained treatment information from medical records, only Oh et al22 (143 patients) examined AHOs (n = 4) by therapy. Hashibe et al20 evaluated AHOs through linkage with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, codes, but results were not presented by treatment, and only 168 patients received chemotherapy (type unspecified). In contrast, we evaluated a wide spectrum of AHOs by type and severity among > 1,200 testicular cancer survivors with detailed treatment information. The resultant CBM score comprises a range of AHOs likely related to testicular cancer and its treatment and to long-term platinum retention. After chemotherapy completion, circulating serum platinum remains measurable at levels up to 1,000 times above normal for 20 years.25 Ongoing endothelial cell and vascular damage26 occur for many years, and long-term serum platinum levels have been significantly related to neuropathy,27 hypertension,28 and hypercholesterolemia.28

Because testicular cancer occurs largely in white males,29 data on Asian patients are sparse. Decreased risks of a higher CBM score in Asian versus white testicular cancer survivors largely reflect the lower occurrence of high-severity grades in Asians for most AHOs. These include known treatment-related toxicities, which possibly reflects differences in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion, among others. Although we adjusted for sociodemographic and health behavior factors, other unmeasured influences may have accounted for this finding, which remain to be confirmed.

Although the CBM score was slightly higher after VIP × 4 than after BEP × 4, the difference was not significant (P = .36). Both are standard chemotherapy regimens for intermediate- and poor-risk disease5,6 and show equivalent survival. Although an early, randomized trial showed that VIP × 4 is associated with greater acute toxicity than BEP × 4,30 no study has subsequently addressed long-term AHOs as we have done. Additional follow-up, as planned for this cohort, is required to quantify further the CBM associated with each regimen. CBM also was similar for BEP × 3 versus EP × 4, the two commonly applied regimens for good-risk disease. In a curable disease such as testicular cancer with a long life expectancy and equivalent therapy options, the availability of AHO data becomes increasingly important to inform treatment decisions.8

The striking association between CBM score and self-reported health indicates that the score captures outcomes that affect patients’ self-perception of health. The risk of worse self-reported health among patients with very high/severe CBM scores rose to > 30-fold compared with those with a score of 0. These results also underscore the need to assess outcomes that affect self-perceived health because these can guide the development of survivorship care strategies that patients value.

To our knowledge, we have performed the first variable-based factor analysis of AHOs in long-term cancer survivors. Prior analyses have largely been conducted in patients either during cancer treatment,31,32 shortly after therapy completion,33,34 or during palliative/hospice care.35 Only Kim et al36 evaluated patients who were either 2 to 5 years (n = 66) or > 5 years (n = 56) postcancer diagnosis, although some were still undergoing treatment. Factor analysis provides insights into groups of conditions that may co-occur and perhaps share etiology. For example, hearing loss and tinnitus reflect known cisplatin-associated damage to the auditory system.10,37 Associations between neuropathy and Raynaud phenomenon have been reported in individuals with no chemotherapy exposure,38,39 although the biologic basis is incompletely understood, and co-occurrence could reflect symptom cross-reporting. Pain is frequently associated with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, with no agents currently available for prevention or treatment.40

The cluster of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes present at the time of clinical evaluation represents components of the metabolic syndrome,41 consistent with studies that report increased metabolic syndrome risk among European testicular cancer survivors.42-45 The co-occurrence of AHOs related to CVD supports European investigations who showed a 1.4-fold to seven-fold higher CVD risk among cisplatin-treated testicular cancer survivors versus either the general population or patients managed with surgery alone.26,46-49 Presentation with one or more of these AHOs suggests closer screening for other cluster-related conditions that could signal an elevated risk for CVD morbidity and mortality.7 Hypogonadism and depression, respectively, represent a biologic consequence of testicular cancer treatment50,51 and possibly associated psychological outcomes. A potential relationship between hypogonadism and depression in the general population has been recognized, with other symptoms including muscle weakness and loss of energy.52-56

An association of erectile dysfunction and thyroid disease has not been previously shown in testicular cancer survivors as it has in noncancer populations.57-63 Of 39 testicular cancer survivors with thyroid disease, 33 and six reported hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism, respectively. Although associations of hypothyroidism57,62,63 and hyperthyroidism57,61-63 with erectile dysfunction were observed in several studies in noncancer populations, a relationship with hypothyroidism was not confirmed in the largest investigation to date,61 possibly because of the low prevalence, and requires additional investigation.

The strong association between vigorous physical activity and lower CBM score as well as with a reduced absolute number of AHOs in prior analyses2 can inform future intervention strategies. Studies of childhood cancer survivors have shown that exercise reduces the risk of late effects, such as CVD,64 and the same likely applies to testicular cancer survivors. The apparent inverse relation between increased risk of a high CBM score and follow-up time is due to the disproportionate contribution of early-onset toxicities (eg, neuropathy, tinnitus), which are more prevalent than later-onset toxicities (eg, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension), which reflects the relatively short median follow-up time and young cohort age.

A major strength of this study is the estimation of both the number and the severity of AHOs in a large testicular cancer survivorship cohort treated primarily with EP × 4, BEP × 3, BEP × 4, or VIP × 4 chemotherapy regimens. Other strengths include the high participation rate (93%), detailed medical chart abstraction, and estimation of risk without the confounding effect of radiotherapy. An inherent limitation to all cross-sectional studies is the inability to assess causality between clinical, sociodemographic, and health behavior characteristics and CBM score. AHOs largely were self-reported without baseline data, similar to previous testicular cancer survivorship studies.21,23,65 As in Geenen et al,15 a limitation is that we could not compare the CBM score with that of a normative population given the unavailability of data. Equivalent weight was assigned to all AHOs, whereas testicular cancer survivorship may weigh these differently; some AHOs capture symptoms that can markedly affect survivors (eg, neuropathy), whereas others encompass conditions treated by medications that may be less bothersome (eg, hypertension). Additional studies are needed to investigate the effect of specific AHOs on health-related quality of life in this understudied population.

In conclusion, at a median follow-up of only 4.2 years, approximately one in five testicular cancer survivors have a CBM score of high, very high, or severe. Of note, no difference in CBM score was observed among survivors who received BEP × 4 versus VIP × 4 chemotherapy or among those given EP × 4 versus BEP × 3, although the long-term monitoring of patients is important. The value of variable clustering analysis in revealing the co-occurrence of AHOs is underscored by our findings and should be considered for other groups of long-term cancer survivors to highlight potential areas of research into the mechanistic bases of toxicities. Ongoing genetic research in the current cohort has already begun to characterize biologic pathways that underlie cisplatin-related toxicities66,67 and that can identify new research opportunities aimed at developing agents to prevent, mitigate, and treat adverse sequelae not only among testicular cancer survivors but also among other survivors after cisplatin-based chemotherapy. In the interim, if confirmed, the current results could inform survivorship care strategies and assist health care providers in identifying conditions, or groups of conditions, for which to screen, counsel, and treat testicular cancer survivors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Members of the Platinum Study Group are Howard D. Sesso (Brigham and Women’s Hospital); Clair Beard and Stephanie Curreri (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute); Lois B. Travis, Lawrence H. Einhorn, Mary Jacqueline Brames, and Kelli Norton (Indiana University); Darren R. Feldman, Erin Jacobsen, and Deborah Silber (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center); Robert J. Hamilton and Lynn Anson-Cartwright (Princess Margaret Hospital); Nancy J. Cox and M. Eileen Dolan (University of Chicago); Robert A. Huddart (The Royal Marsden Hospital); David J. Vaughn, Linda Jacobs, Sarah Lena Panzer, and Donna Pucci (University of Pennsylvania); Debbie Baker, Cindy Casaceli, Chunkit Fung, Eileen Johnson, and Deepak M. Sahasrabudhe (University of Rochester); and Robert D. Frisina (University of South Florida). Members of the Platinum Study Group Advisory Committee are George Bosl (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center), Sophie D. Fossa (Norwegian Radium Hospital), Mary Gospodarowicz (Princess Margaret Hospital), Leslie L. Robison (St Jude Children’s Research Hospital), and Steven E. Lipshultz (Wayne State University).

Appendix

Methods

Study Population

All participants received first-line cisplatin-based chemotherapy for either initial germ cell tumor or recurrence after active surveillance. Participants could not have received subsequent salvage chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or antecedent chemotherapy for another primary cancer. All participants were disease free at the time of clinical assessment.

Data Collection From Medical Records and Clinical Evaluation

Study personnel were trained in person to abstract data using a standard protocol and forms modified from previous investigations11 (Travis LB, et al: J Natl Cancer Inst 86:1450-1457, 1994; Travis LB, et al: J Natl Cancer Inst 87:524-530, 1995; Travis LB, et al: N Engl J Med 340:351-357, 1999; Travis LB, et al: J Natl Cancer Inst 94:182-192, 2002). Detailed data on cancer diagnosis and treatment, including names and doses of all cytotoxic drugs were abstracted directly from medical records.

Sociodemographic Characteristics, Patient-Reported Health Outcomes, and Lifestyle Behaviors

Patient-reported outcomes and lifestyle behaviors were assessed through self-reporting using validated questionnaires.11,12,68-71 To minimize recall bias, we applied strict definitions to assessment times. Validated questionnaires that queried symptoms over the past 4 weeks were selected, and for those adverse health outcomes (AHOs) for which Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 4.03) grading took into account prescription medication use (ie, peripheral sensory neuropathy, pain, kidney disease, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, thromboembolic event, thyroid disease, anxiety/depression, erectile dysfunction, hypogonadism), we only took into account current prescription medication use (with usage for > 1 month), with data provided by the patient at the time of clinical assessment. For sociodemographic characteristics, we assessed current marital and employment status. Self-reported race and education level were determined at the time of enrollment. For health behaviors, we used standardized questions drawn from validated survey tools to assess current or former smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity over the past year.

For health behaviors, we used validated questionnaires to assess current or former smoking status, alcohol consumption, and physical activity over the past year. Exercise was assessed with a validated questionnaire11,12 that asked participants to report their average time per week (over the past year) spent in each of nine recreational activities: walking or hiking (including walking to work); jogging (> 10 min/mile); running (≤ 10 min/mile); bicycling (including stationary bike); aerobic exercise/dance or exercise machines; lower-intensity exercise, yoga, stretching, or toning; tennis, squash, or racquetball; lap swimming; and weight lifting or strength training. Each physical activity was assigned a metabolic equivalent task (MET) value, which is a commonly used metric for describing the relative energy expenditure of a specific type of physical activity (1 MET = 1 kcal/kg/h or the energy cost of sitting quietly).11 The MET values for each activity were then used to calculate MET-hours per week for each participant, and these were grouped into categories of vigorous or nonvigorous physical activity according to standard definitions (Ainsworth, et al: Med Sci Sports Exerc 43:1575-1581, 2011).

Measurement of AHOs

Symptoms related to a single underlying condition were grouped to avoid overcounting (eg, coronary artery disease was defined as a single AHO by combining coronary artery disease, angina, heart attack or myocardial infarction, and related procedures). For 12 AHOs in which current prescription medication use determined grade, medications were only considered if participants started use during or after cancer treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Nonlinear factor analysis used the probit link and WLSMV (weighted least squares means and variance) estimation with Mplus software (Muthén, et al: 2017) and the nonparametric conditional item-pair covariance method of the cross-validated dimensionality evaluation to enumerate contributing traits procedure (Monahan, et al: Appl Psychol Meas 31:483-503, 2007; Zhang, et al: Psychometrika 64:213-249, 1999) using the expl.detect function from the sirt (supplementary item response theory) R package (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sirt) and its default N.est option of a 50-50 split in training and validation data sets for replications.

Table A1.

AHOs That Comprise the Cumulative Burden of Morbidity Score

Table A2.

Definition of the Cumulative Burden of Morbidity Score on the Basis of Number and Severity of Individual Adverse Health Outcomes

Table A3.

Association Among Clinical, Sociodemographic, and Health Behavior Factors and Cumulative Burden of Morbidity Score

Table A4.

Summary of US Studies of Testicular Cancer Survivors

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (1R01 CA157823 to L.B.T. and K07 CA187546 to S.L.K.).

Presented at the 2016 and 2017 ASCO Annual Meetings, Chicago, IL, June 3-7, 2016, and June 2-6, 2017, and the 2016 ASCO Cancer Survivorship Symposium, San Francisco, CA, January 15-16, 2016.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sarah L. Kerns, Chunkit Fung, Deepak M. Sahasrabudhe, Sophie D. Fossa, Lawrence H. Einhorn, Lois B. Travis

Financial support: Lois B. Travis

Administrative support: Lois B. Travis

Provision of study materials or patients: Chunkit Fung, Darren R. Feldman, Robert J. Hamilton, David J. Vaughn, Clair Beard, Robert A. Huddart, Jeri Kim, Christian Kollmannsberger, Deepak M. Sahasrabudhe, Lawrence H. Einhorn, Lois B. Travis

Collection and assembly of data: Chunkit Fung, Darren R. Feldman, Ryan Cook, Lois B. Travis

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Cumulative Burden of Morbidity Among Testicular Cancer Survivors After Standard Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy: A Multi-Institutional Study

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Sarah L. Kerns

No relationship to disclose

Chunkit Fung

Stock or Other Ownership: GlaxoSmithKline

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Exelixis

Research Funding: Astellas Pharma (Inst)

Patrick O. Monahan

Stock or Other Ownership: RestUp

Shirin Ardeshir-Rouhani-Fard

Employment: Eli Lilly (I)

Mohammad I. Abu Zaid

No relationship to disclose

AnnaLynn M. Williams

No relationship to disclose

Timothy E. Stump

No relationship to disclose

Howard D. Sesso

No relationship to disclose

Darren R. Feldman

Research Funding: Novartis, Seattle Genetics

Robert J. Hamilton

Honoraria: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Astellas Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Astellas Pharma, AbbVie

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen Pharmaceuticals

David J. Vaughn

Research Funding: Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Genentech

Clair Beard

No relationship to disclose

Robert A. Huddart

Leadership: Cancer Clinic London

Honoraria: Janssen Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck Sharp & Dohme

Speakers’ Bureau: Pierre Fabre, AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Ipsen, Active Biotech, Merck Sharp & Dohme (Inst), Roche (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Roche, Genentech, MSD

Jeri Kim

Employment: Merck

Stock or Other Ownership: Merck

Christian Kollmannsberger

Honoraria: Pfizer, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Novartis, Seattle Genetics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, Ipsen, Eisai

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer, Novartis

Deepak M. Sahasrabudhe

Consulting or Advisory Role: AXON Communications

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AXON Communications

Ryan Cook

No relationship to disclose

Sophie D. Fossa

No relationship to disclose

Lawrence H. Einhorn

No relationship to disclose

Lois B. Travis

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. : Cancer survivors in the United States: Prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22:561-570, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fung C, Sesso HD, Williams AM, et al. : Multi-institutional assessment of adverse health outcomes among north American testicular cancer survivors after modern cisplatin-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 35:1211-1222, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einhorn LH, Donohue J: Cis-diamminedichloroplatinum, vinblastine, and bleomycin combination chemotherapy in disseminated testicular cancer. Ann Intern Med 87:293-298, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. : Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66:271-289, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanna N, Einhorn LH: Testicular cancer: A reflection on 50 years of discovery. J Clin Oncol 32:3085-3092, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna NH, Einhorn LH: Testicular cancer—discoveries and updates. N Engl J Med 371:2005-2016, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glendenning JL, Barbachano Y, Norman AR, et al. : Long-term neurologic and peripheral vascular toxicity after chemotherapy treatment of testicular cancer. Cancer 116:2322-2331, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oldenburg J, Gietema JA: The sound of silence: A proxy for platinum toxicity. J Clin Oncol 34:2687-2689, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis LB, Fossa SD, Sesso HD, et al. : Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity and ototoxicity: New paradigms for translational genomics. J Natl Cancer Inst 106:dju044, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frisina RD, Wheeler HE, Fossa SD, et al. : Comprehensive audiometric analysis of hearing impairment and tinnitus after cisplatin-based chemotherapy in survivors of adult-onset cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:2712-2720, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chasan-Taber S, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. : Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire for male health professionals. Epidemiology 7:81-86, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Jr, Schucker B, et al. : A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 31:741-755, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, et al. : 2011 Compendium of physical activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc 43:1575-1581, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Cancer Institute: Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, NIH publication 09-7473, 2009.

- 15.Geenen MM, Cardous-Ubbink MC, Kremer LC, et al. : Medical assessment of adverse health outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA 297:2705-2715, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. : Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 355:1572-1582, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haugnes HS, Bosl GJ, Boer H, et al. : Long-term and late effects of germ cell testicular cancer treatment and implications for follow-up. J Clin Oncol 30:3752-3763, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Travis LB, Beard C, Allan JM, et al. : Testicular cancer survivorship: Research strategies and recommendations. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:1114-1130, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brydøy M, Oldenburg J, Klepp O, et al. : Observational study of prevalence of long-term Raynaud-like phenomena and neurological side effects in testicular cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:1682-1695, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashibe M, Abdelaziz S, Al-Temimi M, et al. : Long-term health effects among testicular cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 10:1051-1057, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim C, McGlynn KA, McCorkle R, et al. : Quality of life among testicular cancer survivors: A case-control study in the United States. Qual Life Res 20:1629-1637, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh JH, Baum DD, Pham S, et al. : Long-term complications of platinum-based chemotherapy in testicular cancer survivors. Med Oncol 24:175-181, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reilley MJ, Jacobs LA, Vaughn DJ, et al. : Health behaviors among testicular cancer survivors. J Community Support Oncol 12:121-128, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shinn EH, Basen-Engquist K, Thornton B, et al. : Health behaviors and depressive symptoms in testicular cancer survivors. Urology 69:748-753, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerl RS: Urinary excretion of platinum in chemotherapy-treated long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Acta Oncol 39:519-522, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman DR, Schaffer WL, Steingart RM: Late cardiovascular toxicity following chemotherapy for germ cell tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 10:537-544, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sprauten M, Darrah TH, Peterson DR, et al. : Impact of long-term serum platinum concentrations on neuro- and ototoxicity in cisplatin-treated survivors of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:300-307, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boer H, Proost JH, Nuver J, et al. : Long-term exposure to circulating platinum is associated with late effects of treatment in testicular cancer survivors. Ann Oncol 26:2305-2310, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghazarian AA, Trabert B, Devesa SS, et al. : Recent trends in the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in the United States. Andrology 3:13-18, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nichols CR, Catalano PJ, Crawford ED, et al. : Randomized comparison of cisplatin and etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in treatment of advanced disseminated germ cell tumors: An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Southwest Oncology Group, and Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. J Clin Oncol 16:1287-1293, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baggott C, Cooper BA, Marina N, et al. : Symptom cluster analyses based on symptom occurrence and severity ratings among pediatric oncology patients during myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 35:19-28, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang J, Gu L, Zhang L, et al. : Symptom clusters in ovarian cancer patients with chemotherapy after surgery: A longitudinal survey. Cancer Nurs 39:106-116, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenne Sarenmalm E, Browall M, Gaston-Johansson F: Symptom burden clusters: A challenge for targeted symptom management. A longitudinal study examining symptom burden clusters in breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 47:731-741, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skerman HM, Yates PM, Battistutta D: Cancer-related symptom clusters for symptom management in outpatients after commencing adjuvant chemotherapy, at 6 months, and 12 months. Support Care Cancer 20:95-105, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stapleton SJ, Holden J, Epstein J, et al. : Symptom clusters in patients with cancer in the hospice/palliative care setting. Support Care Cancer 24:3863-3871, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. doi: 10.1177/0193945917701688. Kim M, Kim K, Lim C, et al: Symptom clusters and quality of life according to the survivorship stage in ovarian cancer survivors. West J Nurs Res 10.1177/0193945917701688 [epub ahead of print on April 1, 2017] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauer CA, Brozoski TJ: Cochlear structure and function after round window application of ototoxins. Hear Res 201:121-131, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koszewicz M, Gosk-Bierska I, Jerzy G, et al. : Peripheral nerve changes assessed by conduction velocity distribution in patients with primary Raynaud’s phenomenon and dysautonomia. Int Angiol 30:375-379, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manek NJ, Holmgren AR, Sandroni P, et al. : Primary Raynaud phenomenon and small-fiber neuropathy: Is there a connection? A pilot neurophysiologic study. Rheumatol Int 31:577-585, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. : Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 32:1941-1967, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. : Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 120:1640-1645, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haugnes HS, Aass N, Fosså SD, et al. : Components of the metabolic syndrome in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Ann Oncol 18:241-248, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Haas EC, Altena R, Boezen HM, et al. : Early development of the metabolic syndrome after chemotherapy for testicular cancer. Ann Oncol 24:749-755, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wethal T, Kjekshus J, Røislien J, et al. : Treatment-related differences in cardiovascular risk factors in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. J Cancer Surviv 1:8-16, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.226. Willemse PM, Burggraaf J, Hamdy NA, et al: Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk in chemotherapy-treated testicular germ cell tumour survivors. Br J Cancer 109:60-67, 2013 [Erratum: Br J Cancer 109:295-296, 2013] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haugnes HS, Wethal T, Aass N, et al. : Cardiovascular risk factors and morbidity in long-term survivors of testicular cancer: A 20-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 28:4649-4657, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huddart RA, Norman A, Shahidi M, et al. : Cardiovascular disease as a long-term complication of treatment for testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 21:1513-1523, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meinardi MT, Gietema JA, van der Graaf WT, et al. : Cardiovascular morbidity in long-term survivors of metastatic testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 18:1725-1732, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Nuver J, de Wit R, et al. : Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease in 5-year survivors of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:467-475, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bandak M, Jørgensen N, Juul A, et al. : Testosterone deficiency in testicular cancer survivors –a systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology 4:382-388, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sprauten M, Brydøy M, Haugnes HS, et al. : Longitudinal serum testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone levels in a population-based sample of long-term testicular cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 32:571-578, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amiaz R, Seidman SN: Testosterone and depression in men. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 15:278-283, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eberhard J, Ståhl O, Cohn-Cedermark G, et al. : Emotional disorders in testicular cancer survivors in relation to hypogonadism, androgen receptor polymorphism and treatment modality. J Affect Disord 122:260-266, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gunn ME, Lähteenmäki PM, Puukko-Viertomies LR, et al. : Potential gonadotoxicity of treatment in relation to quality of life and mental well-being of male survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Cancer Surviv 7:404-412, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hintikka J, Niskanen L, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, et al. : Hypogonadism, decreased sexual desire, and long-term depression in middle-aged men. J Sex Med 6:2049-2057, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson JM, Nachtigall LB, Stern TA: The effect of testosterone levels on mood in men: A review. Psychosomatics 54:509-514, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carani C, Isidori AM, Granata A, et al. : Multicenter study on the prevalence of sexual symptoms in male hypo- and hyperthyroid patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:6472-6479, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keller J, Chen YK, Lin HC: Hyperthyroidism and erectile dysfunction: A population-based case-control study. Int J Impot Res 24:242-246, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corona G, Isidori AM, Aversa A, et al. : Endocrinologic control of men’s sexual desire and arousal/erection. J Sex Med 13:317-337, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maggi M, Buvat J, Corona G, et al. : Hormonal causes of male sexual dysfunctions and their management (hyperprolactinemia, thyroid disorders, GH disorders, and DHEA). J Sex Med 10:661-677, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Corona G, Wu FC, Forti G, et al. : Thyroid hormones and male sexual function. Int J Androl 35:668-679, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veronelli A, Masu A, Ranieri R, et al. : Prevalence of erectile dysfunction in thyroid disorders: Comparison with control subjects and with obese and diabetic patients. Int J Impot Res 18:111-114, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krassas GE, Tziomalos K, Papadopoulou F, et al. : Erectile dysfunction in patients with hyper- and hypothyroidism: How common and should we treat? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:1815-1819, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jones LW, Liu Q, Armstrong GT, et al. : Exercise and risk of major cardiovascular events in adult survivors of childhood Hodgkin lymphoma: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 32:3643-3650, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dahl CF, Haugnes HS, Bremnes R, et al. : A controlled study of risk factors for disease and current problems in long-term testicular cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 4:256-265, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dolan ME, El Charif O, Wheeler HE, et al. : Clinical and genome-wide analysis of cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult-onset cancer. Clin Cancer Res 23:5757-5768, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wheeler HE, Gamazon ER, Frisina RD, et al. : Variants in WFS1 and other Mendelian deafness genes are associated with cisplatin-associated ototoxicity. Clin Cancer Res 23:3325-3333, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Postma TJ, Aaronson NK, Heimans JJ, et al. : The development of an EORTC quality of life questionnaire to assess chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: The QLQ-CIPN20. Eur J Cancer 41:1135-1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oldenburg J, Fosså SD, Dahl AA: Scale for chemotherapy-induced long-term neurotoxicity (SCIN): Psychometrics, validation, and findings in a large sample of testicular cancer survivors. Qual Life Res 15:791-800, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ventry IM, Weinstein BE: The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: A new tool. Ear Hear 3:128-134, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD: The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30:473-483, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]