Abstract

Accessory gallbladder in a donor liver allograft is an uncommon anatomical finding that can complicate liver transplantation if unrecognized. This case describes a patient who underwent liver transplantation with a donor graft containing an accessory gallbladder that was obscured during transplantation; as a result, the patient experienced a prolonged postoperative course complicated by multiple readmissions for suspected biloma and intra-abdominal infection. The diagnosis of accessory gallbladder was not made until operative exploration several months after the initial transplant. Removal of the accessory gallbladder has led to resolution of clinical problems.

Accessory gallbladder is an uncommon embryologic phenomenon with a historical incidence of 1 in 3800 based on Boyden's 1926 study of 19000 human cadavers and patients.1 Multiple anatomic configurations have been previously described with the Harlaftis classification in 19772 and more recently with a unified classification system proposed by Causey et al3 in 2010, which included triplicate gallbladders. Distinction is made between true gallbladder duplication (those which arise from a single gallbladder primordium) and accessory gallbladder (those which arise from a second, separate primordia).3,4 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of anatomical variation of duplicate and accessory gallbladder as described by Harlaftis in 1977.

Several case reports have detailed successful laparoscopic and open surgical management of accessory gallbladder.3-6 Given their rarity, however, the most challenging aspect lies not in surgical removal, but in perioperative diagnosis. When present, Kim et al7 have suggested roughly 50% are diagnosed on preoperative imaging. Although some will be identified incidentally during surgery, they can be easily missed—particularly if intrahepatic in location—resulting in delayed diagnosis and complication.4,7,8

Herein we present a unique case of undiagnosed accessory gallbladder in a transplanted liver, causing persistent postoperative infectious complications in the transplant recipient.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 60-year-old man with medical history of end-stage liver disease (model for end-stage liver disease, 22) secondary to hepatitis C virus cirrhosis presented for deceased donor liver transplantation. His preoperative comorbidities included hepatopulmonary syndrome, encephalopathy, congestive heart failure, chronic pain, and depression. Donor characteristics were remarkable for a donation after brain death, hepatitis C virus/hepatitis B virus core antibody positive graft with 10% to 20% macrosteatosis and 10% to 20% microsteatosis on biopsy. The donor cause of death was drug intoxication.

The donor graft was notable for a replaced left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery; in addition, the left gastric artery origin came directly from the aorta, adjacent to the celiac artery. The liver was implanted using a standard bicaval technique and end-to-end portal vein anastomosis. Arterial supply consisted of an anastomosis between recipient common hepatic artery/gastroduodenal artery confluence to the donor aortic Carrel patch encompassing both the celiac and replaced left hepatic artery. Before biliary reconstruction, a standard open cholecystectomy was performed on the donor liver, yielding a 7.8 × 4.2 cm specimen with a cystic duct margin, and was later noted to have signs of chronic cholecystitis with ulceration on pathology. Biliary reconstruction was subsequently performed, consisting of a duct-to-duct anastomosis (end-to-end) between donor and recipient common bile ducts, without use of a biliary stent.

The patient's early postoperative course was notable for a rising serum bilirubin. Investigation included a hepatobiliary iminodiacectic acid (HIDA) scan demonstrating radiotracer accumulation in the gallbladder fossa, initially suggestive of contained biliary leak (Figure 2). Endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) was subsequently performed with stent placement and an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed no evidence of fluid collection or biloma. The patient was discharged with a Jackson-Pratt drain in place due to continued high volume (1000 mL/d) output.

FIGURE 2.

HIDA scan obtained 1 week postoperatively demonstrating radiotracer accumulation in the gallbladder fossa, concerning for contained bile leak.

Two weeks posttransplant, drain output had downtrended, and the drain was removed during clinic follow-up. Within hours, the patient developed abdominal pain, nausea, and profuse vomiting requiring readmission. Computed tomography abdomen pelvis demonstrated a new fluid collection adjacent to the cystic duct stump concerning for bile leak, as well as small bowel dilation reflective of ileus (Figure 3). After a brief period of conservative management for ileus, he was discharged upon return of normal bowel function without a drain in place.

FIGURE 3.

CT abdomen coronal view at 2 weeks posttransplant. A 40-mm rim-enhancing fluid collection was observed adjacent to the cystic duct stump.

Over the next month, he continued to have intermittent epigastric pain radiating to the back and serous drainage from the right aspect of his incision. A repeat CT demonstrated interval increase in size of the rim-enhancing fluid collection within the gallbladder fossa (Figure 4). A CT-guided drain was placed which revealed bilious output and cultures which grew Citrobacter Freundii complex and Enterococcus Faecium. Repeat ERCP demonstrated apparent extravasation of contrast at the level of the cystic duct; a 10 mm by 8 cm covered metal stent was placed within the common bile duct with proximal extension into the common hepatic duct. After this, bilious drain output promptly dropped off, and he was discharged with oral linezolid and IV ertapenem via peripherally inserted central catheter line. Two weeks later, however, he required readmission for recurrent abdominal pain and return of bilious drain output. Computed tomography demonstrated no new evidence of fluid collection, though ERCP again demonstrated bile leak with apparent extravasation of contrast; this time 2 plastic stents were placed through the covered metal stent and into the right hepatic and common hepatic ducts, above the area of the leak. His drain output became clear again with improvement in symptoms.

FIGURE 4.

CT abdomen/pelvis obtained during readmission 6 weeks posttransplant. A rim-enhancing fluid collection within gallbladder fossa was thought to represent biloma.

Sixteen weeks posttransplant, he was again admitted with worsening pain radiating to the back (his drain had been removed 2 weeks previously in clinic). A new CT scan showed an increased subhepatic fluid collection with gas formation (Figure 5). A new drain was placed and cultures grew Candida albicans, Candida gabralta, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, and vancomycin-resistant enterococci; he was again started on broad spectrum IV antibiotics including ertapenem, daptomycin, and micafungin. He underwent ERCP, this time with removal of all 3 stents and placement of a new 10 mm × 10 cm covered metal stent in the common bile duct, covering the cystic duct take-off (It should be noted that the prior stent did not cover this area) (Figure 6). He was discharged with a planned 6-week course of IV antibiotics.

FIGURE 5.

CT abdomen/pelvis obtained on readmission approximately 16 weeks posttransplant. An interval increase in the fluid collection is observed, with gas formation.

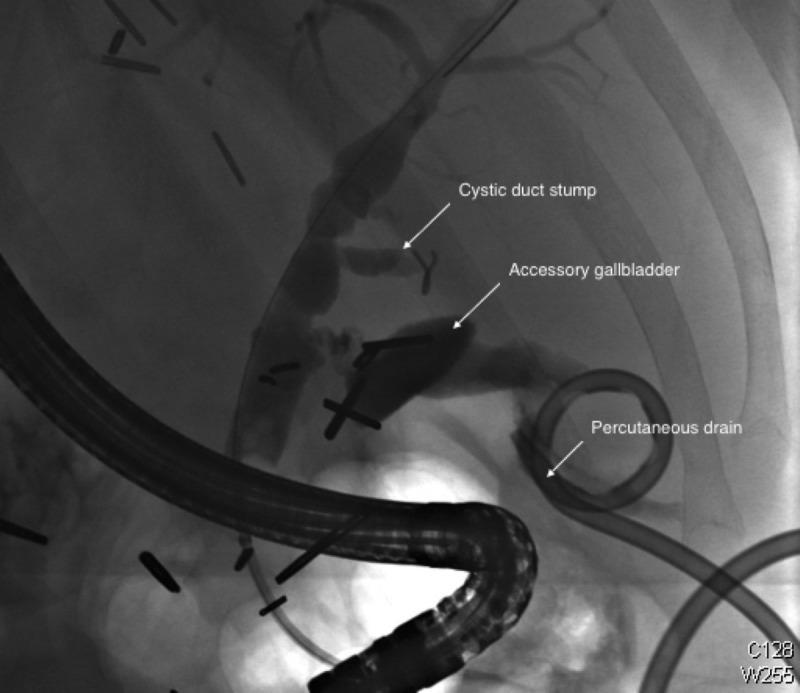

FIGURE 6.

ERCP obtained on readmission approximately 16 weeks posttransplant. Three stents were present and subsequently removed from the biliary tree. The study was thought to demonstrate bile leak; however, what was later identified as an accessory gallbladder can be seen distal to the original cystic duct stump. A percutaneous drain is present in the fluid collection.

Seven months after his index operation, and approximately 10 days following removal of the metal stent he again presented with recurrent bile leak on a surveillance CT scan. Given the patient's prolonged course and treatment failure with several trials of endoscopic management, the decision was made to take the patient for exploratory laparotomy and washout. Intraoperatively, a subhepatic cystic structure was encountered and dissected circumferentially off of the liver parenchyma to the hilum. A structure resembling a cystic duct was identified and was cannulated to perform intraoperative cholangiogram which demonstrated contrast filling into the biliary tree. The duct was doubly ligated, divided, and excised en-bloc with the cystic structure. Pathologic analysis revealed a 10.0 × 4.0 × 1.4 cm extensively disrupted specimen felt to represent an accessory gallbladder. Microscopic examination was performed demonstrating chronic cholecystitis.

Imaging at 2 weeks and 2 months after accessory gallbladder removal revealed postsurgical change without biliary dilatation or subhepatic fluid collections. At 1 year, the patient has not required hospital readmission for complications relating to bile leak.

DISCUSSION

This patient's course was complicated by what was presumed to be a persistent bile leak, requiring multiple readmissions and endoscopic procedures. Ultimately, however, at reoperation he was found to have an accessory gallbladder. Although many case reports have described accessory gallbladder in the context of cholecystitis, to our knowledge, this is the first report in which accessory gallbladder has complicated a liver transplant recipient's postoperative course.

In 1936, Gross9 reviewed 148 cases of congenital gallbladder anomaly, noting numerous variations in the position of accessory gallbladders; although many were found within the gallbladder fossa, others were observed within the gastrohepatic ligament, embedded within the hepatic parenchyma, or even found below the left lobe of the liver. Given that our patient's accessory gallbladder was neither identified during back-table preparation of the donor liver nor during donor cholecystectomy after graft implantation, we suspect our patient's accessory gallbladder was either partially intrahepatic in location or densely adherent to the gallbladder fossa, only becoming evident following removal of the primary gallbladder. Unfortunately there was no cross sectional imaging taken of the donor graft in situ to confirm this. In referencing the ERCP in Figure 6, it appears the accessory gallbladder was in the Ductular or “H-shaped” configuration as described within the Harlaftis classification.

In retrospect, what was thought to represent a bile leak on our patient's initial HIDA scan and ERCP, was in actuality filling of the accessory cystic duct and gallbladder. As such, although his symptoms initially improved with drain placement, multiple interval attempts at drainage in actuality perforated the accessory gallbladder and exacerbated the clinical problem.

CONCLUSIONS

Accessory gallbladder is a rare embryologic phenomenon which can cause considerable morbidity when unrecognized in the context of liver transplantation. It can be especially difficult to diagnose due to anatomic variation, but should be considered in cases with inexplicable or refractory bile leak. This case highlights the diagnostic difficulty in identifying an accessory gallbladder postliver transplantation.

Footnotes

Published online 19 April, 2018.

The authors declare no funding or conflicts of interest.

S.J.K. participated in the drafting of the article. A.S.B. is the editor of the article and participated in writing of the article. D.V. is also an editor of the article and is the primary surgeon involved in the case.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyden EA. The accessory gall‐bladder–an embryological and comparative study of aberrant biliary vesicles occurring in man and the domestic mammals. . 1926;38:177–231. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harlaftis N. Multiple gallbladders. . 1977;145:928–934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Causey MW, Miller S, Fernelius CA, et al. Gallbladder duplication: evaluation, treatment, and classification. . 2010;45:443–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maddox JM, Demers ML. Laparoscopic management of gallbladder duplication: a case report and review of literature. . 1999;3:137–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorecki PJ, Andrei VE, Musacchio T, et al. Double gallbladder originating from left hepatic duct: a case report and review of literature. . 1998;2:337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schroeder C, Draper KR. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for triple gallbladder. . 2003;17:1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim RD, Zendejas I, Velopulos C, et al. Duplicate gallbladder arising from the left hepatic duct: report of a case. . 2009;39:536–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silvis R, van Wieringen AJ, van der Werken CH. Reoperation for a symptomatic double gallbladder. . 1996;10:336–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross RE. Congenital anomalies of the gallbladder: a review of one hundred and forty-eight cases, with report of a double gallbladder. . 1936;32:131–162. [Google Scholar]