Abstract

Background

Depression and/or anxiety during pregnancy have been associated with impaired fetal growth and neurodevelopmental. Because placental imprinted genes play a central role in fetal development and respond to environmental stressors, we hypothesized that imprinted gene expression would be affected by prenatal depression and anxiety.

Methods

Placental gene expression was compared between mothers with prenatal depression and/or anxiety/obsessive compulsive disorder/panic and control mothers without psychiatric history (n=458) in the Rhode Island Child Health Study.

Results

Twenty-nine genes were identified as being significantly differentially expressed between placentae from infants of mothers with both depression and anxiety (n=54), with depression (n=89), or who took perinatal psychiatric medications (n=29) and control mother/infant pairs, with most genes having decreased expression in the stressed group. Among placentae from infants of mothers with depression, we found no differences in expression by medication use, indicating that our results are related to the stressor rather than the treatments. We did not find any relationship between the stress-associated gene expression and neonatal neurodevelopment as measured using the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale.

Conclusions

This variation in expression may be part of an adaptive mechanism by which the placenta buffers the infant from the effects of maternal stress.

Introduction

Stressors during pregnancy, such as traumatic events, low socioeconomic status, and depression and anxiety, are associated with poorer obstetric and infant outcomes including increased risk of preterm birth (1), delayed early cognitive development (2), changes in brain structure and connectivity (3), behavioral and motor differences during early childhood and psychological disorders into adulthood (4). The mechanism by which stressors affect infant development, however, is not yet established but may involve changes in hormone regulation and gene expression in the placenta. The placenta regulates the fetal environment through a variety of functions, ranging from nutrient transport (5) and control of growth factors to hormone signaling (2,6). Alterations to these functions can potentially impact the course of pregnancy and have short- and long-term impacts on offspring health.

To date, studies of the placenta in mediating the effect of prenatal psychosocial stressors on infant health have focused on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis pathway and the genes involved in cortisol regulation and response (4,7). However, other non-neurological outcomes of prenatal stress, such as decreased growth, increased risk of obstetric complications, and differences in placental architecture (2,8) are likely impacted outside of this pathway. In particular, the lower birthweight and slower weight gain, and reduced fetal head circumference growth (3,9) seen among infants of mothers with depression and anxiety are of concern given both the prevalence of these disorders prenatally—up to 23% of women will experience depression during pregnancy (10), and between 15 and 35% will experience anxiety (3), with up to 75% of women experiencing some form of stress during pregnancy (4)—and the link between birthweight and long-term health outcomes. Infants with lower birthweight have been found to have increased risk of type II diabetes (11), cardiovascular disease (12), and mortality (12–14), as well as increased risk of psychiatric disorders (15). Identifying the mechanism by which maternal depression and anxiety affect infant growth outcomes, outside of neurodevelopment, is essential in developing treatments and potentially mediating the effects of prenatal stressors.

Birthweight is partially determined by the placenta, particularly through its regulation of growth and nutrient transport from the mother to the fetus. These functions are controlled in part by a group of epigenetically-regulated, monoallelically-expressed genes, imprinted genes (16), which have been found to be highly sensitive to stressors during pregnancy including exposure to maternal smoking, maternal diet, and other environmental exposures (17). These genes have also been found to be related to neurobehavioral outcomes (18), indicating a possible mechanism by which maternal stress may also be impacting neurodevelopment. A comprehensive look at the expression of all known or putative imprinted genes in the placenta has not yet been undertaken and would provide insight into how the placenta responds to and accommodates maternal stressors. Additionally, these genes may suggest new mechanisms for neurological and HPA axis development.

In this study, we examined the expression levels of 108 known or putatively imprinted genes in placenta samples from newborns born to mothers enrolled in the Rhode Island Children’s Health Study (RICHS) diagnosed with depression and/or anxiety during pregnancy in comparison with control mothers to identify genes that may be related to the placental response to stressors during pregnancy. We also used the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurodevelopmental Scales (NNNS) scores and infant birthweights and head circumference to evaluate the relationship between expression of these genes and infant neurodevelopment and fetal growth.

Patients and Methods

Study Population

Study participants consisted of mother/infant pairs enrolled in RICHS who were recruited from Sept. 1, 2009 to Aug. 7, 2013, at the Women and Infant’s Hospital of Rhode Island (Providence, RI). Mothers of term infants (≥37 weeks gestational age) born large or small for gestational age (≥90th percentile, LGA; ≤10th percentile, SGA) were recruited. Each mother/infant pair was then matched on infant sex, gestational age (±3 days), and maternal age (±2 years) to a pair with a term infant born appropriate for gestational age (AGA). Infants born with life-threatening conditions or congenital or chromosomal abnormalities and non-singleton births were excluded from the study. Women completed an interviewer-based questionnaire to provide demographic and medical history, and obstetric medical chart review provided obstetric and infant outcomes such as birthweight, gestational age, and depression and anxiety/obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)/panic history.

Neurodevelopmental status was evaluated as previously described (19) using the NNNS between 24 hours after birth and hospital discharge (20,21). All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Women and Infants Hospital and Emory University.

Placenta collection, RNA extraction and gene expression profiling

Placental collection, RNA extraction, and probe selection and design, normalization, and Nanostring detection methodology have previously been described (22). Median expression levels of Nanostring measures were compared with whole transcriptome RNAseq analysis for 80 genes for a subset of samples with this data available (23), with a high degree of correlation between the two measures (average Spearman rho = 0.76). After normalization, we removed genes with samples below the background threshold of detection—defined as two standard deviations above the mean of the negative controls, resulting in 676 samples with count data on 108 genes. Fifteen additional samples were removed due to having more than 10 genes with expression outside of three standard deviations of the mean, leaving 661 samples for cohort selection.

Cohort Selection

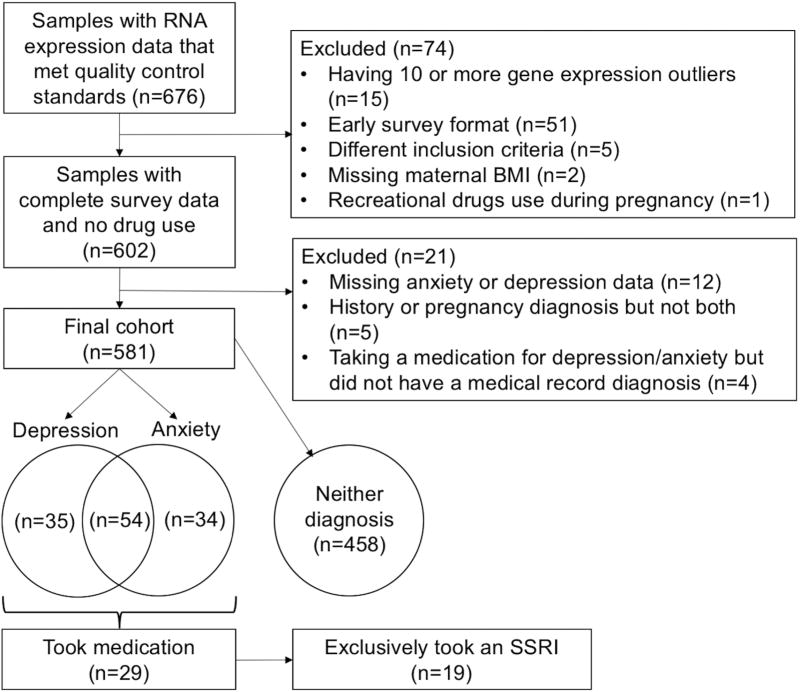

From the 661 samples with imprinting data that met quality control standards, 56 were removed due to early survey format, which was missing several required questions, or having been selected for biomarker analysis using different inclusion criteria from the majority of the samples (Figure 1). Two were removed due to missing BMI data and one for recreational drug use during pregnancy, leaving 602 samples. Data were complete on all variables to be included in the models except maternal smoking prior to pregnancy, for which missing values were recoded as missing. Maternal depression and anxiety status was evaluated using four components of the medical chart review: depression history, anxiety/OCD/panic history, depression during pregnancy, and anxiety/OCD/panic during pregnancy. Twelve participants were excluded due to missing data on these questions. Five participants were excluded due to a history of either depression or anxiety/OCD/panic but no symptoms during pregnancy. Women were considered to be taking a psychiatric medication if they self-reported taking any form of medication used to treat anxiety or depression on the interviewer-based questionnaire. Four women were excluded who reported taking a medication for anxiety but who did not have a diagnosis in their medical record, leaving a final cohort of 581.

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for case and control groups consisting of mother infant pairs from the Rhode Island Child Health Study.

Five case groups were created. The depression group consisted of all women who had both a history of depression and depression during pregnancy (n=89). Similarly, the anxiety group consisted of women with anxiety/OCD/panic prior to and during pregnancy (n=88). The depression/anxiety group (n=54) consisted of those in both the depression and anxiety groups: they had positive answers to having had both depression and anxiety/OCD/panic history and during pregnancy. Of those with either or both diagnoses (n=123), 29 reported taking a psychiatric medication during pregnancy, forming the medication subgroup. Within this subgroup, 19 women were exclusively taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), creating the SSRI subgroup. The control group consisted of 458 women with no depression or anxiety/OCD/panic during or prior to pregnancy.

Gene expression analysis

All analyses and normalizations were performed using R 3.4.0. Gene expression between each of the main three case groups—those with depression, those with anxiety, and those with depression and anxiety—and controls was evaluated separately using an empirical Bayes method via the limma package in R. Additionally, the subgroup of women who used psychiatric medications during pregnancy and controls was also performed, as well as a sensitivity analysis for effect of medication via two separate analyses comparing expression between those in the depression group and those in the anxiety group who were and were not taking psychiatric medications. The potential effect of SSRIs was also evaluated by comparing gene expression in placentae from infants of mothers taking exclusively an SSRI with gene expression in control placentae. All models included maternal age, infant sex, maternal education as a marker of socioeconomic status, maternal pre-pregnancy BMI, and smoking three months prior to pregnancy, as a measure of smoking during early pregnancy. Multiple testing was accounted for with both a Bonferroni adjustment and the Benjamini-Hochberg-based false discovery rate (FDR).

NNNS summary score selection and association of depression/anxiety and gene expression to birthweight and neurodevelopmental outcomes

Linear models were used to evaluate the relationships between NNNS summary scores and depression/anxiety diagnosis for the cohort with mothers with both diagnoses compared to controls. Results were corrected for multiple testing using a Bonferroni correction. For those scores significantly associated with diagnosis, the relationship between NNNS score and gene expression for the genes significant in any of the above comparisons were similarly evaluated with linear models. All linear models included variables previously found to be associated with NNNs scores: maternal education, maternal race/ethnicity, maternal BMI, infant gestational age, infant sex, and delivery method (caesarian section or vaginal).

The relationship between birthweight and depression/anxiety, medication use, and SSRI use was also evaluated using a linear model including maternal age, maternal BMI, and infant gestational age. The relationship between head circumference and depression/anxiety, medication use, and SSRI use was similarly evaluated using a linear model including maternal BMI, maternal education, infant gestational age, and mode of delivery.

Sensitivity analysis

In order to ensure that these results were not due to differences in the proportion of small and large for gestational age infants between case and control groups, analyses were repeated with size for gestational age (small (<10th percentile), large (>90th percentile) or appropriate (≥10th percentile and ≤90th percentile)) included in the model.

Results

Demographics

Mothers in the cohort were, on average, 30.0 years old (SD 5.5) with an average BMI of 26.8 (SD 6.9) (Table 1). The majority had a junior college degree or higher level of education (60.3%) and most were married (66.0%). Smoking prior to pregnancy was reported by 16.5% of mothers and all but one received prenatal care visits. Infants were born, on average, at 39.3 (SD=1.0) gestational weeks, with an average birthweight of 3543.2 grams (SD=660.8) and an average birthweight percentile of 57.7 (SD=33.4). There were fewer female infants than male (47.7%).

Table 1.

Demographic information for women with both depression and anxiety during pregnancy and controls, who had neither diagnosis during or prior to pregnancy.

| Study Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Both Diagnoses and Controls |

Both depression and anxiety |

Neither diagnosis |

|

|

|

|||

| n=512 | n=54 | n=458 | |

|

|

|||

| Maternal Demographics | |||

| Maternal age (years, mean (SD)) | 29.96 (5.50) | 30.33 (5.97) | 29.92 (5.44) |

| BMI (mean (SD))* | 26.82 (6.91) | 29.78 (9.01) | 26.47 (6.55) |

| Maternal Education* (N (%)) | |||

| Any post graduate schooling | 95 (18.6) | 5 (9.3) | 90 (19.7) |

| College graduate | 175 (34.2) | 10 (18.5) | 165 (36.0) |

| Junior college graduate or equivalent | 123 (24.0) | 20 (37.0) | 103 (22.5) |

| High school graduate | 86 (16.8) | 15 (27.8) | 71 (15.5) |

| Less than 11th grade | 33 (6.4) | 4 (7.4) | 29 (6.3) |

| Marital Status (N (%)) | |||

| Married | 338 (66.0) | 31 (57.4) | 307 (67.0) |

| Separated or divorced | 8 (1.6) | 2 (3.7) | 6 (1.3) |

| Single, never married | 166 (32.4) | 21 (38.9) | 145 (31.7) |

| Pregnancy exposures and complications | |||

| Smoked before pregnancy* (N (%)) | 65 (16.5) | 18 (41.9) | 47 (13.4) |

| Received prenatal care (N (%)) | 511 (99.8) | 54 (100.0) | 457 (99.8) |

| Number of prenatal care visits (mean (SD)) | 17.26 (7.41) | 18.89 (8.44) | 17.07 (7.27) |

| Vaginal delivery (vs cesarean section) (N (%)) | 243 (47.5) | 25 (46.3) | 218 (47.6) |

| Gestational diabetes (N (%)) | 46 (9.0) | 9 (16.7) | 37 (8.1) |

| Infant Outcomes | |||

| Infant sex male (N (%)) | 242 (47.3) | 26 (48.1) | 216 (47.2) |

| Infant gestational age* (weeks, mean (SD)) | 39.30 (0.97) | 38.91 (0.84) | 39.35 (0.97) |

| Birthweight (grams, mean (SD)) | 3543.21 (660.82) | 3375.50 (653.98) | 3562.98 (659.53) |

| Birthweight group (N (%)) | |||

| Small for gestational age (<10th percentile) | 82 (16.0) | 11 (20.4) | 71 (15.5) |

| Appropriate for gestational age (10th–90th percentile) | 281 (54.9) | 31 (57.4) | 250 (54.6) |

| Large for gestational age (>90th percentile) | 149 (29.1) | 12 (22.2) | 137 (29.9) |

Significant difference between those with anxiety and depression and those without

Rates of depression and anxiety in the cohort were similar to those reported in the larger US population. Within the final cohort, 15.3% had prenatal depression, 15.2% had prenatal anxiety/OCD/panic, with an overall 21.2% having some form of psychiatric disorder during pregnancy. Recent estimates indicate that up to 23% of women in the US may have minor or major prenatal depression (10). Data on the prevalence of anxiety are less available due to varying definitions of anxiety, but estimates range from 15% to as high as 78% with low to moderate anxiety during pregnancy (3,4).

Mothers in the depression/anxiety group had significantly higher BMIs than controls and were significantly more likely to have less than an 11th grade education level. Additionally, they were significantly more likely to have a higher gravida and to have smoked prior to pregnancy. Infants born to mothers with depression/anxiety had statistically significantly shorter gestational ages, though the difference was only that of several days. No other significant differences between the groups on demographic, obstetric, or other medical history were identified. Of note, there were no differences in prenatal care or number of prenatal visits between the depression/anxiety and control groups. There were no differences in any of the variables examined between mothers with a diagnosis who were taking medications and mothers not taking medications (data not shown).

Relationship between depression/anxiety status and imprinted gene expression

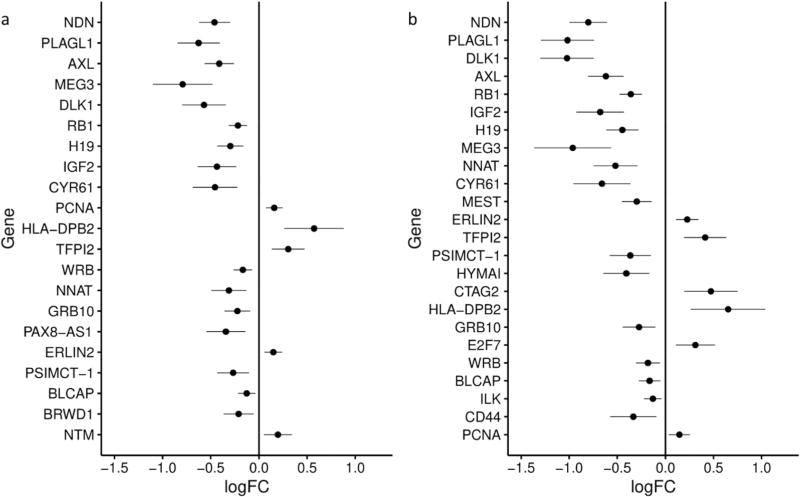

Out of 108 known or putative imprinted genes compared between mothers with depression/anxiety and controls, 11 were found to be differentially expressed at a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level (α=0.05/108=0.0046), with an additional 10 significant at a less-stringent 5% FDR correction (Supplemental Table S1 (online)). For 16 (76.2%) of these genes, expression was decreased in the depression/anxiety group (Figure 2a). To determine if the effect was related to just depression or just anxiety, we repeated the analysis using the depression group and using the anxiety group. For the depression group placentae, two genes were significantly differently expressed in comparison with control placentae at a Bonferroni correction, with three additional genes significantly differently expressed using an FDR cut-off (Supplemental Table S2 (online)). The three genes with decreased expression associated with depression—PLAGL1, DLK1, and NDN—were also among the top four genes with the largest change in expression identified in the analysis of the anxiety/depression group, although the magnitude of the expression change was smaller for the depression group. There were no statistically significant differences in gene expression between mothers with anxiety and controls (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Differences in placental imprinted gene expression between a) placentae from infants whose mothers had both depression and anxiety/obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)/panic during pregnancy (n=54) and infants whose mothers had no psychiatric history before or during pregnancy (n=458) and b) placentae from infants whose mothers took a psychiatric medication during pregnancy (n=29) compared with infants whose mothers had no psychiatric history before or during pregnancy (n=458). For each gene, the log fold change for each comparison is plotted (dot) with the lower and upper confidence interval (horizontal line). The model included maternal age (years), maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index, infant sex, maternal smoking in the three months prior to pregnancy, and maternal education.

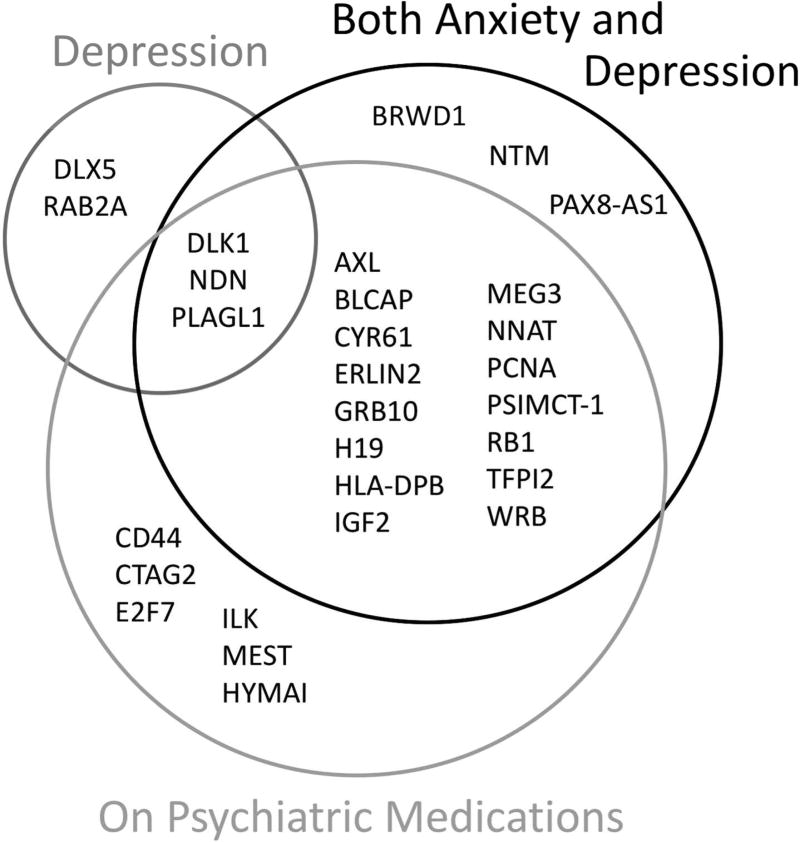

To strengthen our classification of mothers with depression and/or anxiety, we repeated the analysis with a narrowed case group that included only mothers who reported taking a psychiatric medication during pregnancy (Supplemental Table S3 (online)). Gene expression for significantly differentially expressed genes was still mostly decreased in case placentae (75.0% of genes with significant differences, Figure 2b). The majority of the genes that were significant in association with both depression and anxiety were still significant for the medication analysis (Figure 3) and the direction of expression change for genes that were significant for both comparisons remained consistent for all genes. The seven genes with the greatest decreases in expression—MEG3, PLAGL1, DLK1, NDN, CYR61, IGF2, and AXL—were the same in association with both diagnoses and with depression. The decrease in expression for each of these genes was greater in association with taking medication than in association with having both anxiety and depression (Supplemental Figure S1 (online)). The gene with the greatest increase in expression, HLA-DPB2, was also the same for both comparisons, with a larger increase in expression associated with medication than with having both anxiety and depression. Three genes—DLK1, NDN, and PLAGL1—were significantly differently expressed in all three comparisons: depression/anxiety vs control, medication vs control, and depression vs control. These were also among the top four genes with the greatest decrease in expression in the case groups (both depression/anxiety, depression, and medication) compared with controls in all three comparisons.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram showing all genes that were significantly differentially expressed in three comparisons between case placentae and placentae from infants whose mothers had no psychiatric history during or prior to pregnancy. Case groups included 1) infants whose mothers had both depression and anxiety during pregnancy (n=54, “Both Depression and Anxiety”), 2) infants whose mothers had either or both depression and anxiety during pregnancy and reported taking a psychiatric mediation during pregnancy (n=29, “On Psychiatric Medications”), and 3) infants whose mothers had depression during pregnancy (n=89, “Depression”).

To ensure that the observed results were not due to an effect of medication, we preformed two analyses comparing imprinted gene expression between mothers taking medication and mothers not taking medication among (1) those with depression and (2) those with anxiety. No statistically significant differences between the groups were observed (Supplemental Tables S4 and S5 (online)). To explore the potential effect of SSRIs specifically, we repeated the analysis comparing expression in placentae from mothers taking only an SSRI medication to control mothers. All of the genes significantly associated with medication usage were still significant when restricted to SSRIs except for WRB, with the addition of LIN28B, HMNG1, and ZNF331 (Supplemental Table S6 (online)). The 10 genes with the greatest decrease in expression for the medication group—DLK1, PLAGL1, MEG3, NDN, IGF2, CYR61, AXL, NNAT, H19, and HYMAI—were also the 10 genes with the greatest decrease in expression for the SSRI group, but all genes had a greater decrease in expression in the SSRI-only group than the medication group in comparison with controls. Similarly, the 6 genes with increased expression in the case groups—HLA-DPB2, CTAG2, TFPI2, E2F7, ERLIN2, and PCNA—were the same for both comparisons, though the SSRI-associated variations were consistently stronger than the medication-associated variations in imprinted gene expression.

Depression/anxiety and infant birthweight and neurodevelopmental outcomes

In this population, three of the NNNS summary scores were significantly associated with depression/anxiety status after Bonferroni correction: the number of stress/abstinence signs (p<0.0001, Estimate=0.06, Std. Error=0.01), asymmetric reflexes (p=0.005, Estimate=0.73, Std. Error=0.21), and non-optimal reflexes (p=0.01, Estimate=1.12, Std. Error=0.33) were all increased in mothers in the depression/anxiety group. There were no significant relationships between these three scores and any of the genes identified as having significantly differential expression between any of the groups. In this cohort, we found no differences in birthweight or head circumference between infants whose mothers had depression/anxiety and whose mothers did not, nor between mothers who took psychiatric medication during pregnancy, including the subset who took only SSRIs, and controls for either birthweight or head circumference.

Sensitivity analysis

For the comparison between those with both depression and anxiety and controls, IGR1R (p=0.04, logFC=−0.22) and SLC22A18 (p=0.05, logFC=−0.12) were significant after FDR adjustment in the sensitivity analysis for size for gestational age, but were not in the original models. E2F7 (p=0.05, logFC=0.32) was not significantly differentially expressed in women taking SSRIs during pregnancy in comparison with controls. All other genes that were identified in the analyses described above were still significantly differentially expressed between cases and controls when size for gestational age was included in the models. Effect sizes between the two models differed by less than 5% for all comparisions, as so growth status does not appear to be a confounder.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified 21 genes that are differentially expressed in the placenta based on maternal depression/anxiety status during pregnancy, indicating a role for imprinted genes in responding to maternal stressors during pregnancy. To our knowledge, this is the first study to look at expression of the complete set of known and putative imprinted genes, rather than epigenetic regulation of these genes via methylation, and establishes a link between the prior work that found changes in methylation in placenta from mothers exposed to stressors during pregnancy with changes in imprinted gene expression (4). Although the effect sizes appear small, imprinted genes are highly regulated and previous work in this cohort has identified similarly small changes in expression with significant effects on birthweight and neurodevelopment (18,22).

Three of the four genes with the strongest inverse associations with depression and anxiety—PLAGL1, NDN, and DLK1—were also significantly differently expressed in association with depression. These genes may therefore be specifically related to depression as a stressor. The smaller effect change may also indicate that the combination of anxiety and depression results in a larger stressor, generating a larger effect size due to stress. There was no significant effect of anxiety alone on imprinted gene expression, though this may be due to the wide range of levels of anxiety and the high frequency of anxiety within the pregnant population, given that as many as 75% of pregnant women may be exposed to stress during pregnancy (4). Based on this, our anxiety group may have been missing many women who did have anxiety and were instead included in the control group.

To further evaluate the robustness of our observed associations with depression and anxiety, we repeated the analysis using only those women who had taken a psychiatric medication during pregnancy. The majority of genes, including those that were most differentially expressed in the depression/anxiety group, were still significant, but with a greater difference in expression in the medicated group. However, among those with anxiety or depression, there was no statistically significant difference between those who did and did not take medication during pregnancy, and thus the variations in expression are unlikely to be driven by the medications themselves. The stronger inverse associations among those taking medication are instead likely due to these women having a higher level of the depression/anxiety stressor, as they required medication during pregnancy to manage their symptoms. Greater duration of prenatal depression, and therefore greater exposure, increases the risk of developmental disorder in offspring (3), indicating that there may be a dose-dependent relationship between gene expression and stressors.

The majority of women taking a psychiatric medication were taking an SSRI, which have been linked to poorer infant outcomes, including lower birthweight (24), changes in pain and stress regulation (25), and psychiatric disorders into childhood and adolescence (26), but also have been found to potentially mediate the effects of prenatal in mouse models (27,28). We therefore also compared expression in mothers taking only an SSRI to controls and found that all but one gene previously identified were still being significantly differentially expressed. If these changes were due to the medication, we would expect to see more drastic changes in the results when we narrowed the type of medication to only SSRI. To verify that the effects were due to stressors and not due to medications, we compared gene expression in mothers with depression who were taking a medication to those who were not; there were no differences, suggesting that the effects we observed are not due to the medications themselves.

There were several genes which were significantly differentially expressed only in mothers who took SSRIs— LIN28B, HMNG1, and ZNF331— which provide insight into the effects of prenatal SSRI exposure. Literature regarding the epigenetic effects of SSRI on pregnancy is scarce and still inconclusive, with three studies identified by a recent meta-review finding methylation differences in cord blood of infants exposed to SSRI during pregnancy and three studies finding no effect (29). Since it is well-established that SSRIs easily cross the placenta to the fetus (25), determining the effect of these medications could help determine safety during pregnancy.

Of the genes with the largest decreases in expression between groups—MEG3, PLAGL1, DLK1, NDN, CYR61, IGF2, and AXL—several have been identified as being involved in neurodevelopment and growth. MEG3/DLK1, which are controlled by a shared imprinting cluster, have been found to be downregulated in intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), while MEG3 and PLAGL1 have been found to be differentially expressed in IUGR placentae (30). IGF2 is a growth suppressor and expression in the chorionic villus has been to be associated with birthweight (16). NDN, which we previously found to be associated with birthweight (23), along with MEG3 and PLAGL1, were previously found to be upregulated in LGA infants compared with SGA infants, while DLK1 and IGF2 were upregulated in LGA infants compared with both SGA and AGA infants (22). MEG3 and IGF2 have also been studied in relation to depression and stress during pregnancy. Both have been found to be differentially methylated in cord blood from infants of women who experienced depression during pregnancy (31,32). MEG3 has also been associated with toddler behavior scores (33). Maternal prenatal anxiety has been associated with decreased methylation at IGF2 imprinting control regions in cord blood (31). Our work provides a group of genes that warrant further exploration in those with these stressors.

To evaluate whether these changes in placental imprinted gene expression were maladaptive for neurodevelopment and growth, we looked at NNNS scores, birthweight, and head circumference. Although we found differences in three NNNS summary scores, with a higher number of stress/abstinence signs, more asymmetric reflexes and more non-optimal reflexes in the infants whose mothers had depression/anxiety than those without, these scores were not associated with expression levels of any of the genes that were differentially expressed between the groups. The lack of association between neurodevelopmental outcomes and gene expression implies that these differentially expressed genes may represent a placental adaptation to protect the infant from the effects of maternal stress. This mechanism is supported by the greater differences we observed in mothers who experienced more extreme stressors, as indicated by our finding that mothers who required medication during pregnancy, a potentially more extreme phenotype, had greater decreases in expression for many of the significant genes than did mothers with depression and anxiety. These more extreme changes may represent a more extreme buffer established by the placenta to protect the infant from the effects of maternal stressors.

Additionally, although maternal stressors are known to have a negative impact on infant growth (34), we saw no differences in birthweight or head circumference in those infants born to mothers with prenatal stressors, indicating that, despite the maternal stress in this cohort, infant growth was not apparently affected. The RICHS cohort, however, consists of healthy, full-term infants from a population with higher socioeconomic status than many studies of prenatal stress focus on. Much of the prior work on NNNS scores and prenatal stress, outside of this cohort, has focused on women experiencing severe stressors such as drug use and treatment (35,36). Therefore, mothers in the RICHS population may not be exposed to sufficient stressors to see the changes identified in infant outcomes. Instead, imprinted genes may be allowing the placenta to adapt to allow for protected infant growth and development within a normative range of stress. Future work in a population with more severe stressors is needed to clarify the point at which these placental adaptations are no longer sufficient to protect the infants from maternal stress.

Since we did not screen each participant for depression and anxiety as part of this study, but rather relied on medical chart review for diagnosis, there is potential for misclassification. If this were the case, however, we would expect these misclassifications to weaken the difference between controls and cases and bias our results to the null, which would decrease our ability to identify any true differences in expression between cases and controls. Since we were able to identify significant differences, despite this risk of misclassification, these differences are either very strong associations or misclassification is not affecting our results. We also do not have a scale of depression and cannot compare various severities of this stressor. Despite this, we identified 21 genes with differential expression between those with psychiatric stressors during pregnancy and controls, indicating that the mechanism behind placental response to stress may be similar despite the psychiatric diagnosis or severity. Because our groups are highly similar for most demographic variables, we were able to focus on the stress that is just generated by maternal depression and anxiety.

Overall, we have identified differences in imprinted gene expression in placentae from mothers with prenatal depression and anxiety, which provide a potential mechanism for attenuating the effects of maternal stressors during pregnancy. Changes in these genes may be an adaptive response of the placenta to help protect the infant from maternal stressors and thus buffer the stressors’ effects on newborn phenotypic outcomes. These genes may also be future targets for pharmacological and behavioral interventions. Some psychiatric medications have been found to affect epigenetics and expression of the genes that regulate epigenetic imprints (37–39); better understanding of such genes could one day allow appropriate treatment to attenuate the effects of maternal depression and anxiety during pregnancy, improving long-term health of these infants and potentially interrupting transgenerational transmission of these diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (NIEHS R01ES022223; NIMH R01MH094609).

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest:

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Field T. Infant Behavior and Development Prenatal depression effects on early development: A review. Infant Behav Dev [Internet] 2011;34:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.09.008. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters CS, Hay DF, Simmonds JR, van Goozen SHM. Antenatal depression and children’s developmental outcomes: Potential mechanisms and treatment options. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet] 2014;23:957–71. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0582-3. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00787-014-0582-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheinost D, Sinha R, Cross SN, et al. Does prenatal stress alter the developing connectome? Pediatr Res [Internet] 2017;81:214–26. doi: 10.1038/pr.2016.197. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/pr.2016.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryan J, Mansell T, Fransquet P, Saffery R. Does maternal mental well-being in pregnancy impact the early human epigenome? Epigenomics [Internet] 2017;9:313–32. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0118. Available from: https://www.futuremedicine.com/doi/full/10.2217/epi-2016-0118?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz P, Powell TL, Jansson T. The Role of Placental Nutrient Sensing in Maternal-Fetal Resource Allocation. Biol Reprod [Internet] 2014;91:1–10. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.121798. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25122064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beijers R, Buitelaar JK, de Weerth C. Mechanisms underlying the effects of prenatal psychosocial stress on child outcomes: beyond the HPA axis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet] 2014;23:943–56. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0566-3. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00787-014-0566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Togher KL, Treacy E, O’Keeffe GW, Kenny LC. Maternal distress in late pregnancy alters obstetric outcomes and the expression of genes important for placental glucocorticoid signalling. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janssen AB, Kertes DA, McNamara GI, et al. A Role for the Placenta in Programming Maternal Mood and Childhood Behavioural Disorders. J Neuroendocrinol [Internet] 2016;28:1–6. doi: 10.1111/jne.12373. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4988512/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis AJ, Austin E, Knapp R, Vaiano T, Galbally M. Perinatal Maternal Mental Health, Fetal Programming and Child Development. Healthc (Basel, Switzerland) [Internet] 2015;3:1212–27. doi: 10.3390/healthcare3041212. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27417821%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4934640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashley JM, Harper BD, Arms-Chavez CJ, LoBello SG. Estimated prevalence of antenatal depression in the US population. Arch Womens Ment Health [Internet] 2016;19:395–400. doi: 10.1007/s00737-015-0593-1. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00737-015-0593-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker DJP. The Developmental Origins of Adult Disease. Eur J Epidemiol [Internet] 2003;18:733–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1025388901248. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3582917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risnes KR, Vatten LJ, Baker JL, et al. Birthweight and mortality in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol [Internet] 2011;40:647–61. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq267. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/40/3/647/744207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wennerström CE, Simonsen J, Melbye M. Long-Term Survival of Individuals Born Small and Large for Gestational Age. [cited 2017 May 9];PLoS One [Internet] 2015 10:e0138594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138594. Available from: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0138594&type=printable. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watkins WJ, Kotecha SJ, Kotecha S. All-Cause Mortality of Low Birthweight Infants in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence: Population Study of England and Wales. PLoS Med [Internet] 2016;13:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002018. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4862683/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Donnell KJ, Meaney MJ. Fetal origins of mental health: The developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis. Am J Psychiatry [Internet] 2017;174:319–28. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16020138. Available from: http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16020138?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore GE, Ishida M, Demetriou C, et al. The role and interaction of imprinted genes in human fetal growth. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci [Internet] 2015;370:1–12. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0074. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsit CJ. Influence of environmental exposure on human epigenetic regulation. J Exp Biol [Internet] 2015;218:71–9. doi: 10.1242/jeb.106971. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25568453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green BB, Kappil M, Lambertini L, et al. Expression of imprinted genes in placenta is associated with infant neurobehavioral development. Epigenetics [Internet] 2015;10:834–41. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1073880. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4623032/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appleton AA, Murphy MA, Koestler DC, et al. Prenatal Programming of Infant Neurobehaviour in a Healthy Population. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol [Internet] 2016;30:367–75. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12294. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5054721/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tronick EZ, Olson K, Rosenberg R, Bohne L, Lu J, Lester BM. Normative Neurobehavioral Performance of Healthy Infants on the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Network Neurobehavioral Scale. Pediatrics [Internet] 2004;113:641–67. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/113/Supplement_2/641.full.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lester BM, Tronick EZ, LaGasse L, et al. Summary statistics of neonatal intensive care unit network neurobehavioral scale scores from the maternal lifestyle study: a quasinormative sample. Pediatrics [Internet] 2004;113:668–75. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/113/Supplement_2/668.long. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kappil MA, Green BB, Armstrong DA, et al. Placental expression profile of imprinted genes impacts birth weight. Epigenetics [Internet] 2015;10:842–9. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2015.1073881. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4623427/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Litzky JF, Deyssenroth MA, Everson TM, et al. Placental imprinting variation associated with assisted reproductive technologies and subfertility. Epigenetics [Internet] 2017;0:1–9. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2017.1336589. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2017.1336589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glover ME, Clinton SM. Of rodents and humans: A comparative review of the neurobehavioral effects of early life SSRI exposure in preclinical and clinical research. Int J Dev Neurosci [Internet] 2016;51:50–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2016.04.008. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brummelte S, Glanaghy emc, Bonnin A, Oberlander TF. Developmental Changes in Serotonin Signaling: Implications for Early Brain Function, Behavior and Adaptation. Neuroscience [Internet] 2017;342:212–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.037. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5310545/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malm H, Brown AS, Gissler M, et al. Gestational Exposure to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Offspring Psychiatric Disorders: A National Register-Based Study. J Am Acad child Adolesc psychiatry [Internet] 2016;55:359–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.02.013. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4851729/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salari AA, Fatehi-Gharehlar L, Motayagheni N, Homberg JR. Fluoxetine normalizes the effects of prenatal maternal stress on depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in mouse dams and male offspring. Behav Brain Res [Internet] 2016;311:354–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.05.062. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2016.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiryanova V, Meunier SJ, Vecchiarelli HA, Hill MN, Dyck RH. Effects of maternal stress and perinatal fluoxetine exposure on behavioral outcomes of adult male offspring. Neuroscience [Internet] 2016;320:281–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.064. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anne-Cathrine F, Viuff, Pedersen LH, Kyng K, Staunstrup NH, Borglum A, Henriksen TB. Antidepressant medication during pregnancy and epigenetic changes in umbilical cord blood: a systematic review. Clin Epigenetics [Internet] 2016;8:94. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0262-x. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5015265/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piedrahita JA. The role of imprinted genes in fetal growth abnormalities. Birth Defects Res (Part A) Clin Mol Teratol [Internet] 2011;91:682–92. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20795. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3189628/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansell T, Novakovic B, Meyer B, et al. The effects of maternal anxiety during pregnancy on IGF2/H19 methylation in cord blood. Transl Psychiatry [Internet] 2016;6:e765. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.32. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27023171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Murphy SK, Murtha AP, et al. Depression in pregnancy, infant birth weight and DNA methylation of imprint regulatory elements. Epigenetics [Internet] 2012;7:735–46. doi: 10.4161/epi.20734. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4161/epi.20734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuemmeler BF, Lee CT, Soubry A, et al. DNA methylation of regulatory regions of imprinted genes at birth and its relation to infant temperament. Genet Epigenetics [Internet] 2016;8:59–67. doi: 10.4137/GEG.S40538. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5127604/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paz MS, Smith LM, LaGasse LL, et al. Maternal depression and neurobehavior in newborns prenatally exposed to methamphetamine. Neurotoxicol Teratol [Internet] 2009;31:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.11.004. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684459/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heller NA, Logan BA, Morrison DG, Paul JA, Brown MS, Hayes MJ. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Neurobehavior at 6 weeks of age in infants with or without pharmacological treatment for withdrawal. Dev Psychobiol [Internet] 2017;59:574–82. doi: 10.1002/dev.21532. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/dev.21532/abstract;jsessionid=E89CAECCB7649C68FABD32CD4510841D.f03t01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salisbury AL, Lester BM, Seifer R, et al. Prenatal cocaine use and maternal depression: Effects on infant neurobehavior. Neurotoxicol Teratol [Internet] 2007;29:331–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.12.001. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1955229/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karsli-Ceppioglu S. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Psychiatric Diseases and Epigenetic Therapy. Drug Dev Res [Internet] 2016;77:407–13. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21340. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ddr.21340/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malhi GS, Outhred T. Opportunities for translational research in the epigenetics of mood disorders: a comment to the review by Robert M. Post. Bipolar Disord [Internet] 2016;18:460–1. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12421. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bdi.12421/abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weaver ICG, Champagne FA, Brown SE, et al. Reversal of Maternal Programming of Stress Responses in Adult Offspring through Methyl Supplementation: Altering Epigenetic Marking Later in Life. J Neurosci [Internet] 2005;25:11045–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3652-05.2005. Available from: http://www.jneurosci.org/content/25/47/11045.long. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.