Abstract

Background

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are widely prescribed during psychiatric treatment. Unfortunately, their misuse has led to recent surges in overdose emergency visits and drug-related deaths.

Methods

Electronic health record data from a large healthcare system were used to describe racial/ethnic, sex, and age differences in BZD use and dependence. Among patients with a BZD prescription, we assessed differences in the likelihood of subsequently receiving a BZD dependence diagnosis, number of BZD prescriptions, receiving only one BZD prescription, and receiving 18 or more BZD prescriptions. We also estimated multivariate hazard models and generalized linear models, assessing racial/ethnic differences after adjustment for covariates.

Results

In both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, Whites were more likely than Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians to have a BZD dependence diagnosis and to receive a BZD prescription. Racial/ethnic minority groups received fewer BZD prescriptions, were more likely to have only one BZD prescription, and were less likely to have 18 or more BZD prescriptions. We identified greater BZD misuse among older patients but no sex differences.

Conclusions

Findings from this study add to the emerging evidence of high relative rates of prescription drug abuse among Whites. There is a concern, given their greater likelihood of having only one BZD prescription, that Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians may be discontinuing BZDs before their clinical need is resolved. Research is needed on provider readiness to offer racial/ethnic minorities BZDs when indicated, patient preferences for BZDs, and whether lower prescription rates among racial/ethnic minorities offer protection against the progression from prescription to addiction.

Keywords: Benzodiazepines, BZD, BZD dependence, mental health, mental illness, racial/ethnic disparity, drug, drug misuse, drug dependence, psychoactive, anxiety, alcohol withdrawal, insomnia, muscle relaxation, panic disorder, seizures, prescription, prescription, treatment

1. Introduction

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are a widely prescribed class of medications indicated for the treatment of insomnia, anxiety, for muscle relaxation, panic disorder, seizures, and alcohol withdrawal (Chen et al., 2011; Chouinard, 2004; Möhler et al., 2002). However, BZD misuse1 is a public health concern given its prevalence and significant association with increases in medication overdose, emergency department visits, and drug-related deaths (Jones et al., 2013; SAMHSA, 2010). BZDs are taken in excess of the maximal clinical dose by one to six percent of the population (Petitjean et al., 2007; Quaglio et al., 2012) and are often deliberately misused by patients to increase the effect of other drugs such as alcohol or opioids (Crane and Lemanski, 2004; Darke, 1994). Given the high rates of co-use of opioids and BZDs identified in the literature (greater than 50% of opioid users reported BZD co-use in multiple studies (Jones et al., 2012)), and the rapidly escalating rates of opioid use in the U.S., a better understanding of BZD prescription and misuse patterns is needed. On its own, misuse of BZDs can cause deficits in learning, attention, and memory, as well as depression, injurious falls, and traffic accidents (Barker et al., 2004; Pariente et al., 2008). The prescription of BZDs has been increasing at an annual rate of 12% (Kao et al., 2014), and this is largely driven by their increased usage for the treatment of anxiety by primary care physicians (Cascade and Kalali, 2008).

Despite risks of benzodiazepine misuse, benzodiazepines remain an important tool for clinicians for anxiety (especially panic disorder), muscle relaxation, seizures, and alcohol withdrawal treatment (Chen et al., 2011; Chouinard, 2004; Möhler et al., 2002). These conditions require clinicians to rapidly assess potential benefits and risks of misuse when deciding whether to prescribe or discontinue these medications. Factors influencing clinician decisions to prescribe benzodiazepines are not well understood, but there is evidence to support that clinicians prescribe differentially to racial/ethnic minority groups. In one recent study, for example, Whites were more likely than other racial groups to receive benzodiazepine prescriptions on discharge from a psychiatric inpatient unit after adjustment for patient diagnosis and severity (Peters et al., 2015). Similar patterns have been observed for other types of psychotropic medications, including opioids, where it has been found that Whites were more likely to receive an opioid than Black, Hispanic, or Asian patients even after adjustment for pain severity (Pletcher et al., 2008).

Gender has also been identified as a factor in prescribing, with women tending to be more likely than men to obtain BZD prescriptions (Olfson et al., 2015), though no prior study has assessed whether these gender differences vary by race/ethnicity. Analyses of long-term prescriptions of BZD should also account for the increasing number of BZD prescriptions for older patients while recognizing the association of long-term BZD use with the risks of falls and cognitive impairment among older patients (Olfson et al., 2015; Partiniti et al., 2002; Pollmann et al., 2015).

Clinicians’ expectations about risks of BZD abuse and the potential safety risk of prolonged use are likely to play a role in their decision to prescribe and/or discontinue these medications (Anthierens et al., 2007). Such expectations may be grounded in clinician perceptions of the sociodemographic profile of patients in their patient panel that have recently misused BZDs (Choudhry et al., 2006; Cioffi, 2001). These expectations could be an important mediator of racial/ethnic disparities in appropriate prescribing of this class of medications. Unfortunately, there is little rigorous evidence to rely on in determining whether or not a patient is at high risk of misusing BZDs, and even fewer studies exist in U.S. healthcare settings (Kroll et al., 2016). Within the time constraints of a typical primary care or psychiatric medication management visit, prescribers may rely on heuristics based on subjective experience that do not reflect the actual prevalence of misuse (Balsa and McGuire, 2001). For example, clinicians might rate an older White female as having a low likelihood of abuse behavior, while evidence supports that they have heightened risk. A patient’s physical appearance and frequency of emergency department visits are frequently factored into clinical decision-making. Studies identifying discordance between the epidemiology of addiction to prescription medications and prescription patterns imply that clinicians’ prior beliefs may at times be misinformed. For example, Pearson et al. (2006) found that, despite Whites being more likely to both use and misuse BZDs than racial/ethnic minorities, Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to have their benzodiazepine prescriptions discontinued even when no indications of misuse existed.

This paper uses a unique electronic health record dataset from an urban health care system that serves a predominantly low-SES, publicly insured, and racial/ethnic/linguistic minority population to assess the significance of sociodemographic and diagnostic predictors of BZD prescription patterns, providing exploratory empirical evidence to assist clinicians and administrators in identifying populations at higher and lower risk for BZD misuse. Building upon prior literature on racial/ethnic differences in prescription medication addiction, this paper also tests the hypothesis that, among those receiving a BZD prescription, Whites are more likely than racial/ethnic minorities to misuse BZD, to have a greater number of BZD prescriptions, and to be among the highest utilizers of BZD prescriptions. We also test the hypothesis that clinicians will be more likely to provide only one BZD prescription to Black, Hispanic, and Asian patients compared to White patients.

2. Methods

2.1 Description of the sample

Data were from electronic health records of patients in a medium sized urban healthcare system in the New England area that provides services to approximately 140,000 patients per year. The healthcare system has a network of three hospitals and fifteen community-based clinics that provide primary care, inpatient and outpatient specialty mental health care, and intensive outpatient substance use treatment. The data include medication events in the 32 months between January 1, 2013 and September 1, 2015 (the latest time point for which data were available). Diagnoses were identified from outpatient and inpatient primary care and specialty treatment during this same time period.

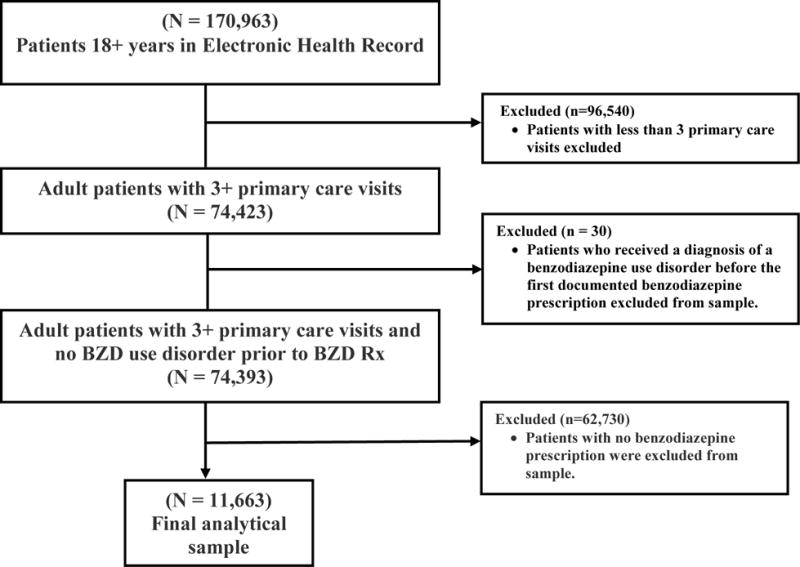

We start with a sample of 170,963 patients 18 years and older. In order to ensure that patients in the sample were regular patients at the health care system under study, patients were excluded if they had less than three primary care visits during the 32-month time period of the study. This was done to increase the likelihood that selected patients received all of their BZD treatment in the healthcare system under study. (Data are not available for other nearby healthcare systems.) Including only those with three or more primary care visits reduces the sample to 74,423. Of these, 11,693 had one or more benzodiazepine prescription. A small number (30) of these individuals received a diagnosis of a benzodiazepine use disorder diagnosis before the first documented benzodiazepine prescription and were dropped, leaving a sample of 11,663, and 6,474 patients with 2 or more benzodiazepine prescriptions. The final analytic sample of patients is more likely to be non-Hispanic White, female, and older than the overall adult patient population at this healthcare system. See Figure 1 for a schematic of the development of the final analytical sample.

Figure 1.

Development of Final Analytical Sample

Note: Hazard rates of a diagnosis of BZD dependence are measured over time subsequent to the date of the receipt of the first BZD prescription and right censored at September 1, 2015.

Data: Electronic health records between January 1, 2013 and September 1, 2015. Sample excludes patients who received diagnosis of dependence before their first benzodiazepine prescription observed and who had less than three primary care visits at the health care institution. n=11,663

2.2 Dependent variables

Our dependent variables characterize a full set of behaviors related to the intensity of use and misuse of BZDs (misuse of BZD is here defined as use in the 95th quantile of BZD prescriptions or higher or a diagnosis of BZD dependence in the clinical record subsequent to an initial BZD prescription). The first dependent variable characterizing BZD use is the number of BZD prescriptions over the data collection period. The second dependent variable of BZD use is the probability of having only one BZD prescription. The third dependent variable, representing BZD misuse, is the probability of receiving 18 or more BZD prescriptions (the 95th quantile of number of prescriptions). The 95th quantile of service use has been used in prior studies to characterize extreme use of overall and behavioral health care (Cook and Manning 2009; Cook et al., 2013). Other cut points at the high end of the distribution (e.g., 90th quantile, 97.5th quantile) were considered but not presented because disparity results were similar in magnitude and significance. The fourth dependent variable, representing BZD misuse, is the likelihood that a patient prescribed a BZD would subsequently receive a diagnosis for BZD dependence, defined as a diagnosis of dependence on a “sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic” (ICD-9=304.1X) in the treatment diagnosis field of the electronic health record (EHR).

2.3 Sociodemographic and clinical variables

Covariates in multivariate analyses representing sociodemographic differences are race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, Black or Other race, or Hispanic), sex (male and female), and age (18-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65+ years of age). In order to assess whether racial/ethnic differences were moderated by sex, race/ethnicity was interacted with sex in the model. Interactions between sex and age were also entered to improve model fit (Appendix Table 12). Models were further adjusted for diagnosis of substance use disorder (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, opioid, tobacco, pain medications), 0/1 indicators of having a substance use disorder diagnosis at a treatment event during the data analysis period. We included a variable indicating receiving treatment for two or more substance use disorders as a measure of severity given the association with severe social, medical, and psychiatric impairment (Agrawal et al., 2007; Schwartz et al., 2010). Models were further adjusted for diagnosis of mental health disorder (depression anxiety, bipolar, PTSD, and sleeping disturbance), 0/1 indicators of having one of these mental health disorder diagnoses for a treatment event during the data analysis period.

2.4 Statistical analysis

We first describe our sample by presenting unadjusted rates of benzodiazepine use and covariates (service use patterns and sociodemographic characteristics) by race/ethnicity. T-tests were used for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

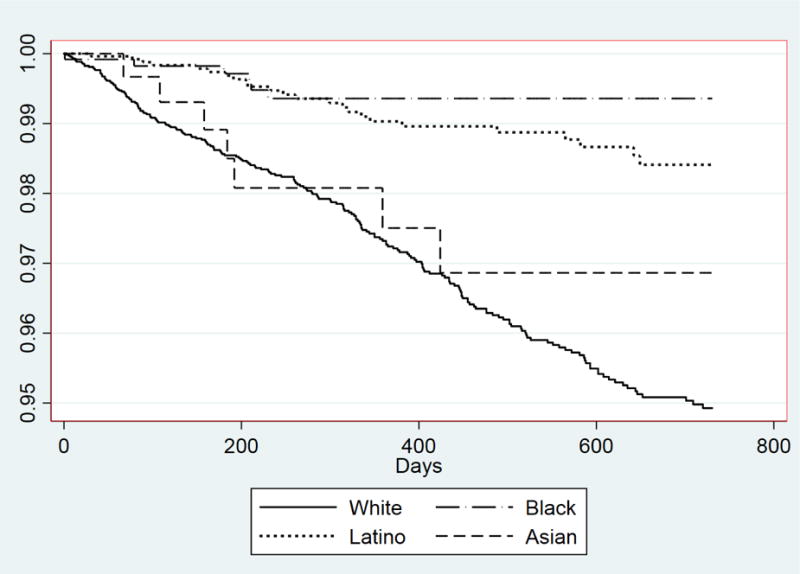

To measure racial/ethnic differences in receiving a diagnosis of BZD dependence in the clinical record subsequent to a BZD prescription, we estimated Kaplan-Meier survival function curves to account for racial/ethnic differences in the amount of exposure time in the data and the right-censoring of patients (to account for the probability that treatment for a SUD diagnosis could occur after September 1, 2015) (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2008). These curves demonstrate differences in the cumulative hazard of receiving a BZD dependence diagnosis graphically. Separate curves were created for non-Latino Whites, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians. The proportion of the number of cases with BZD dependence was plotted over the number of patients prescribed a BZD in each time period at daily intervals. The hazard rates associated with these curves were calculated and statistically compared using Cox proportional hazards models after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics and the existence of substance use disorder and mental health disorder diagnoses.

To assess race/ethnicity, sex, and age as predictors of only one BZD prescription and 18 or more prescriptions (the 95th quantile of prescriptions), we estimated logistic regression models and adjusted for substance use disorder and mental health disorder diagnoses. For the continuous number of BZD prescriptions variables, we estimated a generalized linear model (GLM) with quasi-likelihoods (McCullagh and Nelder, 1989), a form of nonlinear least squares modeling. Expected number of prescriptions E(y|x) were modeled directly as μ(x’β) where x are the predictors and μ is the link between the observed raw scale of prescriptions y and the linear predictor, x’β. The conditional variance of y is a power of expected number of prescriptions. Thus, E(y|x) = μ(x’β) and Var(y|x) = μ((x’β))λ, where μ is a log transformation, and λ is 2, making the distribution of the variance equivalent to a gamma distribution of the expected number of prescriptions. Stata 14 was used to estimate these models.

3. Results

Table 1 describes our sample of individuals who received a BZD prescription in the 32-month data collection period. Whites with at least one BZD prescription were older than their racial/ethnic minority counterparts, Asians were less likely to be female than other racial/ethnic groups, and Whites had more outpatient, ER, and IP visits than other racial/ethnic minorities. Rates were similar across racial/ethnic groups in treatment for marijuana and cocaine, and Whites were more likely to receive treatment for alcohol, tobacco, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.

Table 1.

Comparison of Demographics, Service Use, and Diagnoses Among Patients Who Had At Least One BZD Prescription During 2013–2015.

| White (n=7,179) |

Black (n=1,265) |

Latino (n=2,854) |

Asian (n=365) |

Total (n=11663) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Benzodiazepine Prescriptions Mean (SD) | 5.3 (7.8) |

3.6*** (5.6) |

3.5*** (5.7) |

2.9*** (4.6) |

4.6 (7.1) |

| Probability of having only 1 BZD prescription | 39% | 53%*** | 55%*** | 58%*** | 45% |

| Probability of being in the 95th quantile (18+ Rx) of BZD prescription | 7% | 4%*** | 3%*** | 1%*** | 6% |

| Percentage with BZD dependence diagnosis in the electronic health record | 3.0% | 0.5%** | 0.8%*** | 1.9%* | 2.2% |

| Age (Mean (SD)) | 51.5 (17.1) |

48.3*** (14.4) |

46.4*** (16.5) |

48.2*** (19.1) |

49.8 (16.6) |

| Sex (Female) | 63% | 65% | 69%*** | 56%** | 65% |

| Number of outpatient visits (BH) | 3.7 | 2.5*** | 2.5*** | 1.8*** | 3.2 |

| Number of ER visits (BH) | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3*** | 0.1** | 0.3 |

| Number of inpatient visits (BH) | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 4*** | 0.03 | 0.7 |

| Substance Use Disorder (SUD) Diagnoses | |||||

| Alcohol | 19% | 15%*** | 15%*** | 13%*** | 17% |

| Marijuana | 2% | 2% | 2% | 0.2%* | 2% |

| Cocaine | 11% | 11% | 11% | 9% | 11% |

| Opioid | 29% | 37%*** | 37%*** | 41%*** | 32% |

| Tobacco | 30% | 21%*** | 15%*** | 9%*** | 25% |

| Pain Meds | 44% | 42% | 45% | 34%*** | 44% |

| 2 or more SUD diagnoses | 24% | 24% | 24% | 22% | 24% |

| Mental Health Disorder Diagnoses | |||||

| Depression | 31% | 28%* | 34%** | 25%* | 31% |

| Anxiety | 49% | 32%*** | 44%*** | 30%*** | 45% |

| Bipolar | 10% | 7%*** | 4%*** | 5%*** | 8% |

| Psychosis | 2% | 6%*** | 2% | 3% | 3% |

| PTSD | 11% | 12% | 10% | 7%* | 11% |

| Sleeping disturbance | 12% | 11% | 12% | 10% | 12% |

Note: Sample excludes patients who received diagnosis of dependence before their first BZD prescription observed in the time period of 1/1/2013-9/1/2015 and who had less than three primary care visits at the health care institution.

BH: Behavioral Health (mental health and/or substance use treatment visits)

For patients with benzodiazepine dependence diagnosis, we only report their behavioral health services use, other diagnoses prior to being diagnosed with benzodiazepine dependence.

=P<0.001,

= P<0.01,

=P<0.05: level of significance for comparisons between racial/ethnic minorities and Whites

A large overall percentage (45%) of individuals had only one BZD prescription. Blacks, Latinos and Asians were significantly more likely than Whites to have only one BZD prescription (53%, 55%, 58%, and 39%, respectively; Table 1). These significant differences persisted after adjustment for demographic, SUD and mental health disorder diagnoses (Table 2, panel 2). Female sex was not a significant predictor of having only one BZD prescription; older age groups were significantly less likely to have only one BZD prescription compared to 18-24 year olds (Table 2, panel 2).

Table 2.

Comparison by Race/Ethnicity, Adjusting for Demographics, Substance Use, and Mental Health Diagnoses Among Patients Who Had At Least One Benzodiazepine Prescription Between 1/1/2013 and 9/1/2015 (N=11,663).

| # of BZD prescriptions | Probability of having only 1 BZD prescription | Probability of being in the 95th quantile (18+ Rx) of BZD prescription | Hazard rate of receiving a BZD dependence diagnosis in the electronic health record | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Coeff | SE | sig. | Coeff | SE | sig. | Coeff | SE | sig. | Coeff | SE | sig. | |

| Race (ref White) | ||||||||||||

| Black | −1.06 | 0.20 | *** | 0.08 | 0.01 | *** | −0.02 | 0.01 | * | 0.18 | 0.08 | *** |

| Latino | −1.31 | 0.15 | *** | 0.12 | 0.01 | *** | −0.03 | 0.005 | *** | 0.20 | 0.08 | *** |

| Asian | −1.20 | 0.36 | *** | 0.10 | 0.03 | *** | −0.03 | 0.01 | * | 0.43 | 0.28 | |

| Sex (Female) | −0.08 | 0.13 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.006 | 0.004 | 1.33 | 0.45 | ||||

| Age (ref 18–24) | ||||||||||||

| 25-34 | .29 | .34 | −0.07 | .02 | ** | 0.006 | .01 | 1.23 | .64 | |||

| 35-44 | .98 | .34 | * | −0.10 | .02 | *** | .02 | .01 | * | .66 | .35 | |

| 45-54 | 1.78 | .34 | *** | −0.15 | .02 | *** | .04 | .01 | *** | .87 | .44 | |

| 55-64 | 2.31 | .34 | *** | −0.21 | .02 | *** | .05 | .01 | *** | 1.08 | .54 | |

| 65+ | 2.08 | .35 | *** | −0.23 | .02 | *** | .04 | .01 | *** | 1.47 | .74 | |

| SUD Diagnoses | ||||||||||||

| Alcohol | 0.46 | 0.19 | * | −0.07 | 0.01 | *** | 0.008 | 0.006 | .77 | 0.13 | ||

| Marijuana | 0.95 | 0.48 | * | −0.07 | 0.03 | * | 0.03 | 0.016 | 0.28 | 0.16 | * | |

| Cocaine | 0.26 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.0003 | 0.007 | 1.13 | 0.18 | ||||

| Opioid | 0.50 | 0.16 | ** | 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.005 | * | 3.90 | 0.61 | *** | |

| Tobacco | 0.81 | 0.15 | *** | −0.04 | 0.01 | *** | 0.02 | 0.005 | *** | 2.08 | 0.29 | *** |

| pain meds | 0.76 | 0.14 | *** | −0.05 | 0.01 | *** | 0.02 | 0.005 | *** | 0.71 | 0.10 | * |

| 2+ SUD Diagnoses | 0.93 | .23 | *** | −0.03 | 0.02 | * | 0.02 | 0.008 | *** | 2.03 | 0.34 | *** |

| Mental Health Disorder Diagnoses | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 0.85 | 0.14 | *** | −0.08 | 0.01 | *** | 0.01 | 0.005 | ** | 1.43 | 0.19 | ** |

| Anxiety | 2.51 | 0.13 | *** | −0.20 | 0.01 | *** | 0.05 | 0.004 | *** | 1.60 | 0.23 | *** |

| Bipolar | 2.20 | 0.23 | *** | −0.17 | 0.02 | *** | 0.05 | 0.008 | *** | 1.02 | 0.20 | |

| PTSD | 3.34 | 0.21 | *** | −0.17 | 0.01 | *** | 0.09 | 0.007 | *** | 0.91 | 0.17 | |

| Sleeping disturbance | 1.25 | 0.19 | *** | −0.05 | 0.01 | *** | 0.04 | 0.006 | *** | 0.69 | 0.13 | * |

| Constant | 1.50 | 0.12 | *** | 0.65 | 0.01 | *** | −0.01 | 0.004 | ** | |||

Notes: Sample excludes patients who received diagnosis of BZD dependence before their first benzodiazepine prescription observed in the time period of 1/1/2013-9/1/2015.

Regression models identify the independent association of racial/ethnic group indicators with the four dependent variables, after adjustment for socio-demographics, SUD diagnoses and mental health diagnoses.

Regression models include interactions between race and sex, and interactions between age and sex (See Appendix Table 13 for full set of regression coefficients, including coefficients on variable interactions)

=P<0.001,

= P<0.01,

=P<0.05

Whites had a greater number of BZD prescription fills than their racial/ethnic minority counterparts in unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 2, panel 1) and were more likely to be in the group receiving an extreme number of prescriptions (18 or more over a three-year period) in unadjusted and adjusted analyses (Table 2, panel 3). Female sex was not a significant predictor of number of BZD prescription fills or being in the group with an extreme number of prescriptions. Nearly all older age groups were significantly more likely to have more BZD prescription fills and to be in the group with an extreme number of prescriptions compared to members of the 18-24 age group.

Figure 2 shows graphically that Whites and Asians with a BZD prescription had a greater cumulative hazard over time than their Black and Latino counterparts of subsequently receiving a BZD dependence diagnosis in the clinical record. In adjusted Cox proportional hazard models, Whites had a greater hazard than their racial/ethnic minority counterparts of developing BZD dependence subsequent to receiving a prescription (Table 2, panel 4). Sex and age were not significant predictors of developing BZD dependence. Significant predictors of developing BZD dependence were opioid abuse, receipt of pain medication, and treatment for diagnosis of anxiety, bipolar disorder, psychosis, PTSD, and a sleep disturbance.

Figure 2.

Cumulative hazard rates of BZD dependence diagnosis.

4. Discussion

This is the first known study to utilize longitudinal EHR data to identify sociodemographic differences in BZD prescription patterns and dependence after initial BZD prescription. We identify variation in BZD use with a primary focus on racial/ethnic differences, and a secondary focus on sex and age differences, in order to assist clinicians and administrators in identifying populations at higher and lower risk of BZD misuse. We found that Whites had more BZD prescription fills, were more likely to have extreme numbers of BZD prescriptions, and were more likely to subsequently receive a BZD dependence diagnosis than Blacks, Latinos, and Asians. Our findings of misuse of BZD (defined as an extremely large number of prescriptions or BZD dependence) provides further evidence that prescription medication abuse disproportionately impacts the White population in the United States (Case and Deaton, 2015). In all analyses, females were no more or less likely to misuse BZD, and older patients were more likely to be high users of BZD. The finding that patients age 55 years and older are at an increased risk of taking an extreme number of prescriptions is of particular concern given the association between long-term BZD use and the risks of falls and cognitive impairment among older patients (Olfson et al., 2015; Partiniti et al., 2002; Pollmann et al., 2015). This provides further evidence that BZDs continue to be prescribed to patients who are at high risk for benzodiazepine-related adverse events (Kroll et al., 2016).

Racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to only have one BZD prescription, raising concern that there may be a disparity in discontinuation. Prior studies have shown that race/ethnicity heavily influences physician perceptions, with Black patients more likely to be assessed as at risk for noncompliance, substance abuse, and as having inadequate social support to adhere to recommendations (Van Ryn and Burke, 2000). Clinician perceptions of risk of noncompliance may be influential in the decision of whether to prescribe BZDs, given their potential for misuse and the safety risks that come with prolonged use. Pletcher et al. (2008) concluded in their study of opioid use that it was unlikely that the greater prescription of opioids to White patients represented an appropriate pattern of care and that racial bias could not be ruled out as a possibility.

A second possible contributor to reduced BZD use among racial/ethnic minorities compared to Whites is a strong preference to avoid the use of BZD medications among these groups. While preference for BZD medications has not been well investigated, there is evidence that racial/ethnic minorities are less likely than Whites to prefer other psychotropic medications such as antidepressants (Cooper and Miranda, 2004).

Several limitations should be noted. While time was used to rule out reverse temporal relationships between treatment patterns and BZD dependence documented in the electronic health record, it is possible that the onset of BZD dependence occurred before the prescriptions were documented in the EHR. At minimum, these predictive models allow for the identification of patients within the healthcare system that are likely to benefit from prevention activities. Second, though we set the inclusion criteria to include only those that had at least three primary care visits during the time of study, it is still possible that patients received BZD prescriptions or diagnoses of BZD dependence at other healthcare systems in the area. This presents a problem in our racial/ethnic difference analysis if these missing medication and service use data vary by race/ethnicity, although we have no evidence or rationale that this is the case. Third, the identified sociodemographic differences may be explained by a select group of providers in the healthcare system with prescribing patterns that disproportionately impact certain subgroups. Assessing the role of patient socioeconomic status (SES) both as a control and a key explanatory variable would also be important, but these data were not available. Future studies with data that include SES variables and that link prescriptions and prescribers should be conducted to better understand the role of clinicians and the sociodemographic makeup of their panels on BZD prescription patterns. Fourth, it is difficult to assess the appropriateness of the BZD prescription patterns described in this study given the lack of information in the electronic health record regarding severity, function, BZD dependence, and response to the medication. The dependent variables of mean number of BZD prescriptions and only 1 BZD prescriptions provide only descriptive comparisons of use across racial/ethnic groups. It is probable, however, that >18 prescriptions of BZD medications is likely to represent inappropriate use of the medication given the increased risk of dependence and impaired cognitive functioning with unrestricted long-term use (Baldwin et al., 2013; Dell’osso and Lader, 2013; Lader, 2011), and multiple provider guidelines recommend that BZD prescription be limited to a short duration (Ashton, 1994; Dell’Osso et al., 2015).

Despite these limitations, we provide evidence from an urban health care system representative of safety net health care institutions in the US that Whites are more likely to misuse BZDs and to have high numbers of BZD prescriptions compared to racial/ethnic minorities, and racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to have only one BZD prescription. We have described potential mechanisms for these racial/ethnic differences that call for future studies on the patient preferences and physician perceptions of patient misuse and noncompliance of BZD prescriptions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Racial/ethnic differences in benzodiazepine (BZD) dependence and misuse were identified.

Whites with a BZD prescription had a higher risk of a BZD dependence diagnosis.

Minorities were more likely than whites to receive only one BZD prescription.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This work was funded by Research Grant 7R01DA034952 (The National Institute on Drug Abuse), which supported Dr. Cook’s time during the analysis and drafting stages of the study. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Misuse is defined in prior studies as the “medical or lay use of a drug for a disease state not considered to be appropriate by the majority” Marks, J. 2012. The benzodiazepines: Use, overuse, misuse, abuse: Springer Science and Business Media. For the purposes of this study, we have a more specific definition (see Methods section).

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Contributors

All authors contributed to the design of the work, the interpretation of data, and the drafting and revising of critically important intellectual content. Drs. Cook and Wang acquired and analyzed the data. Dr. Cook and Timothy Creedon made a major contribution to the design, interpretation of data, and drafting and revising of critically important intellectual content. All authors approved of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Benjamin Cook, Timothy Creedon, Ye Wang, Chunling Lu, Nicholas Carson, Piter Jules, Esther Lee, and Margarita Alegría have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT, Madden PA, Bucholz KK, Heath AC. A latent class analysis of illicit drug abuse/dependence: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Addiction. 2007;102:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthierens S, Habraken H, Petrovic M, Christiaens T. The lesser evil? Initiating a benzodiazepine prescription in general practice: A qualitative study on GPs’ perspectives. Scand. J Prim Health Care Suppl. 2007;25:214–9. doi: 10.1080/02813430701726335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton H. Guidelines for the rational use of benzodiazepines. When and what to use. Drugs. 1994;48:25–40. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DS, Aitchison K, Bateson A, Curran HV, Davies S, Leonard B, Nutt DJ, Stephens DN, Wilson S. Benzodiazepines: Risks and benefits: A reconsideration. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:967–71. doi: 10.1177/0269881113503509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsa AI, McGuire TG. Statistical discrimination in health care. Am J Health Econ. 2001;20:881–907. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M, Crowe SF. Cognitive effects of long-term benzodiazepine use: A meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2004;18:37–48. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200418010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascade E, Kalali AH. Use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of anxiety. Psychiatry. 2008;5:21–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect B Biol Sci. 2015;112:15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Berger CC, Forde DP, D’Adamo C, Weintraub E, Gandhi D. Benzodiazepine use and misuse among patients in a methadone program. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry NK, Anderson GM, Laupacis A, Ross-Degnan D, Normand SL, Soumerai SB. Impact of adverse events on prescribing warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: Matched pair analysis. BMJ. 2006;332:141–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38698.709572.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouinard G. Issues in the clinical use of benzodiazepines: Potency, withdrawal, and rebound. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;65:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi J. A study of the use of past experiences in clinical decision making in emergency situations. Int J Nurs Stud. 2001;38:591–9. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(00)00096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Manning WG. Measuring racial/ethnic disparities across the distribution of health care expenditures. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:1603–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Manning WG, Alegria M. Measuring racial/ethnic disparities across the distribution of mental health care expenditures. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2013;16:3–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Miranda J. Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:120–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane EH, Lamanski N. Benzodiazepines in drug abuse-related emergency department visits: 1995–2002. US Department of Health and Human Services Drug Abuse Warning Network Report. 2004;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. The use of benzodiazepines among injecting drug users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1994;13:63–69. doi: 10.1080/09595239400185741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso B, Albert U, Atti AR, Carmassi C, Carra G, Cosci F, Del Vecchio V, Di Nicola M, Ferrari S, Goracci A, Iasevoli F, Luciano M, Martinotti G, Nanni MG, Nivoli A, Pinna F, Poloni N, Pompili M, Sampogna G, Tarricone I, Tosato S, Volpe U, Fiorillo A. Bridging the gap between education and appropriate use of benzodiazepines in psychiatric clinical practice. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1885–909. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S83130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell’osso B, Lader M. Do benzodiazepines still deserve a major role in the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A critical reappraisal. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28:7–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher FP, Ross-Degnan D. Racial disparities in access after regulatory surveillance of benzodiazepines. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:572–79. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Survival Analysis: Regression modeling of time to event data. Second. Wiley; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Mogali S, Comer SD. Polydrug abuse: A review of opioid and benzodiazepine combination use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;125:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309:657–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao M, Zheng P, Mackey P. Trends in benzodiazepine prescription and co-prescription with opioids in the United States, (2002––2009) J Pain. 2014;15(Suppl. 41) [Google Scholar]

- Kroll DS, Nieva HR, Barsky AJ, Linder JA. Benzodiazepines are prescribed more frequently to patients already at risk for benzodiazepine-related adverse events in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:1027–34. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3740-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lader M. Benzodiazepines revisited--will we ever learn? Addiction. 2011;106:2086–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J. The benzodiazepines: Use, overuse, misuse, abuse. Springer Science and Business Media; Chicago: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized Linear Models. Chapman and Hall; London: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Möhler H, Fritschy JM, Rudolph U. A new benzodiazepine pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:2–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:136–142. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariente A, Dartiques JF, Benichou J, Letenneur L, Moore N, Fourrier-Reglat A. Benzodiazepines and injurious falls in community dwelling elders. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:61–70. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterniti S, Dufouil C, Alperovitch A. Long-term benzodiazepine use and cognitive decline in the elderly: The epidemiology of vascular aging study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22:285–293. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200206000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson SA, Soumerai S, Mah C, Zhang F, Simoni-Wastila L, Salzman C, Cosler LE, Fanning T, Gallagher P, Ross-Degnan D. Racial disparities in access after regulatory surveillance of benzodiazepines. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:572–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SM, Knauf KQ, Derbidge CM, Kimmel R, Vannoy S. Demographic and clinical factors associated with benzodiazepine prescription at discharge from psychiatric inpatient treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petitjean S, Ladewig D, Meier CR, Amrein R, Wiesbeck GA. Benzodiazepine prescribing to the Swiss adult population: Results from a national survey of community pharmacies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;22:292–8. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328105e0f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299:70–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollmann AS, Murphy AL, Bergman JC, Gardner DM. De-prescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults: A scoping review. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16:19. doi: 10.1186/s40360-015-0019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaglio G, Pattaro C, Gerra G, Mathewson S, Verbanck P, Des Jarlais DC, Lugoboni F. High dose benzodiazepine dependence: Description of 29 patients treated with flumazenil infusion and stabilised with clonazepam. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198:457–62. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz BS, Wetzler S, Swanson S, Sung SC. Subtyping of substance use disorders in a high-risk welfare-to-work sample: A latent class analysis. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:366–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2012. National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010. (HHS publication no. (SMA) 12-4733, DAWN series D-38). [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–28. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.