Abstract

Purpose

We evaluate if cigarette smoking and/or nicotine dependence predicts cannabis use disorder symptoms among adolescent and young adult cannabis users and whether the relationships differ based on frequency of cannabis use.

Methods

Data were drawn from seven annual surveys of the NSDUH to include adolescents and young adults (age 12 to 21) who reported using cannabis at least once in the past 30 days (n=21,928). Cannabis use frequency trends in the association between cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorder symptoms were assessed using Varying Coefficient Models (VCM’s).

Results

Over half of current cannabis users also smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days (54.7% SE 0.48). Cigarette smoking in the past 30 days was associated with earlier onset of cannabis use, more frequent cannabis use and a larger number of cannabis use disorder symptoms compared to those who did not smoke cigarettes. After statistical control for socio-demographic characteristics and other substance use behaviors, nicotine dependence but not cigarette smoking quantity or frequency was positively and significantly associated with each of the cannabis use disorder symptoms as well as the total number of cannabis symptoms endorsed. Higher nicotine dependence scores were consistently associated with the cannabis use disorder symptoms across all levels of cannabis use from 1 day used (past month) to daily cannabis use, though the relationship was strongest among infrequent cannabis users.

Conclusion

Prevention and treatment efforts should consider cigarette smoking comorbidity when addressing the increasing proportion of the US population that uses cannabis.

Keywords: Smoking, Nicotine Dependence, Cannabis, Cannabis use disorder symptoms

1. Introduction

Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit substance in the U.S. and adolescence and young adulthood represents the period of greatest risk for the development of cannabis use and cannabis use disorder symptoms (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015). Early use has been found to be associated with poor academic performance, higher dropout rates, greater unemployment, lower life satisfaction (Stiby et al., 2015; Mokrysz et al., 2014; Georgiades et al., 2007) and deficits in executive function (Gruber et al., 2012). The Monitoring the Future Study reports that 9.4% of 8th graders, 23.9% of 10th graders and 35.6% of 12th graders used cannabis in the past year (Johnston et al., 2016). Nearly 8% of 19- to 22-year-olds report using cannabis daily, double the rate of use among young adults in 1996 (Schulenberg et al., 2016). Though often viewed as less addictive than other licit and illicit substances (Nutt et al., 2007), cannabis dependence has been shown to develop in nearly one in ten (approximately 9%) individuals who have ever tried cannabis (Wagner and Anthony, 2002). Those initiating cannabis use during adolescence, compared to those who first use in young adulthood, have also been found to be at increased risk for experiencing cannabis use disorder symptoms soon after initiation and developing associated problems in adulthood (Degenhardt et al., 2001; Mewton et al., 2010). In a recent study examining adolescent cannabis users who initiated within the past two years, nearly one-third of those using cannabis no more than 5 days per month reported experiencing at least some cannabis use disorder symptoms (Dierker et al., 2017).

A strong association between tobacco cigarette smoking and cannabis use has been found in cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations in which both cigarette use and symptoms of nicotine dependence have been shown to be associated with cannabis use (Kapusta et al., 2007; Lai et al., 2000; Ramo et al., 2013), cannabis dependence (Ream et al., 2008), a decreased likelihood of successful quitting of cannabis use (Haney et al., 2013) and increased risk of relapse to illicit substance use among those with remitted substance use disorders (Weinberger et al., 2017). In fact, the prevalence of cannabis use has been increasing over the past decade (Compton et al., 2016) with estimates of cigarette smoking among current cannabis users ranging from 41–94% (Peters et al., 2012). Although support for the order of onset has been mixed, with evidence for cigarette smoking being a risk factor for later cannabis use (Beenstock and Rahav, 2002; Bentler et al., 2002), and cannabis use a risk factor for tobacco initiation and the development of nicotine dependence symptoms (Badiani et al., 2015; D'Amico and McCarthy, 2006; Patton et al., 2005), their co-occurrence has been consistently established.

The mechanisms underlying this association remain somewhat less clear. The link between cigarette smoking and cannabis use has been discussed with regard to the role each behavior plays in increasing risk for exposure to the other substance, either through a “gateway effect” in which the use of one substance may increase susceptibility to the other, or through regular pairing and/or co-administration of each substance. For example, in one study among college students who reported smoking both tobacco and cannabis, 65% had smoked tobacco and cannabis in the same hour (Tullis et al., 2003). Additionally, in cases of simultaneous use, the repeated pairing of cannabis and tobacco (e.g., blunts) is believed to lead to each substance serving as a behavioral cue for the other (Amos et al., 2004; Highet, 2004). Alternative explanations for the observed associations include genetic and individual factors thought to increase the risk of use for multiple substances (Huizink et al., 2010). Given that substance use disorder symptoms are known to play a central role in sustaining regular and chronic use, their role in the link between cigarette smoking and cannabis use may shed light on these alternate mechanisms of association.

While it is true that exposure to cannabis is a necessary requirement for developing cannabis use disorder symptoms, recent evidence suggests that frequency of cannabis use is a markedly imperfect index for determining an individual’s probability of developing DSM-5 cannabis use disorder symptoms among recent onset cannabis users drawn from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH; Dierker et al., 2017). Further, previous research has shown alcohol use disorders (Dierker et al., 2011; Dierker et al., 2016) to be a risk factor for DSM-IV nicotine dependence and DSM-IV nicotine dependence symptoms even when smoking cigarettes infrequently and/or at low levels of use. Moreover, cross-over between alcohol use disorder symptoms and nicotine dependence symptoms may promote chronic smoking independent of one’s level of smoking or drinking. For example, an investigation of young adult smokers from the National Epidemiologic Study of Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) demonstrated that daily smokers with DSM-IV alcohol dependence were at increased risk for DSM-IV nicotine dependence regardless of how much they smoked (Dierker and Donny, 2008). Similarly, based on a 4-year longitudinal follow-up of adolescents at risk for chronic smoking behavior, we have previously demonstrated that, among novice smokers at entry into the study, the association between alcohol-related problems at baseline and smoking frequency at the 4 year follow-up could be largely explained by experiences of nicotine dependence symptoms measured by the Nicotine Dependence Symptom Scale, rather than directly through measures of smoking or drinking behavior (Dierker et al., 2016).

This evidence independently linking alcohol use disorder symptoms to nicotine dependence rather than smoking or drinking per se provides evidence for a developmental mechanism that recognizes symptoms associated with one type of substance use disorder as a sign or signal for symptoms of another substance use disorder regardless of levels of exposure to either substance. If nicotine dependence is independently linked to cannabis use disorder symptoms over and above level of exposure to either substance, this would provide evidence that nicotine dependence may indicate sensitivity to cannabis use disorder symptoms across a potentially wide range of cannabis use behaviors. To our knowledge, there has been little research evaluating the link between nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorders symptoms controlling for level of exposure to both substances. Given this gap in the literature, the present study aims to (1) determine the prevalence of cannabis use disorder symptoms among adolescents and young adults who do or do not smoke cigarettes within a nationally representative sample of current cannabis users; (2) evaluate whether cigarette smoking or nicotine dependence better predicts cannabis use disorder symptoms among adolescents and young adults using both substances; (3) determine the strength of the association between nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorders symptoms according to the frequency with which cannabis is used and (4) investigate differences in these relationships across sociodemographic subgroups. Specifically, we were interested in whether the relationships between cigarette and cannabis use and their association with nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorder symptoms are consistent across gender, age (adolescents vs. young adults), and race/ethnicity subgroups.

We hypothesize that, while frequency of cannabis use will be a significant predictor of cannabis use disorders symptoms, nicotine dependence will also be independently associated with individual cannabis use disorder symptoms and with the total number of cannabis use disorder symptoms reported. With respect to the strength of the association between nicotine dependence scores and cannabis use disorder symptoms across the continuum of cannabis use frequency from 1 day per month to daily use, we hypothesize that nicotine dependence scores will be significantly associated with cannabis use disorder symptoms even among those reporting infrequent use, given the evidence that the development of cannabis use disorder symptoms in the context of nicotine dependence need not be driven by heavy use.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

The sample was drawn from seven annual NSDUH surveys (2009–2015), consisting of n=21,928 individuals age 12 to 21 who reported cannabis use at least once in the past 30 days. The 2009 survey was chosen as the earliest cohort due to changes to the mental health module between 2008 and 2009. The NSDUH utilized multistage area probability methods to select a representative sample of the noninstitutionalized U.S. civilian population aged 12 or older. Persons living in households, military personnel living off bases, and residents of non-institutional group quarters including college dormitories, group homes, civilian dwellings on military installations, as well as persons with no permanent residence are included. More than half of the sample was male (58.8% SE 0.44) and the mean age was 18.3 years (SE=0.02). Racial/ethnic representation was 60.0% Non-Hispanic White, 14.9% non-Hispanic Black, 18.3% Hispanic, and 6.8% Other.

All procedures performed in this study involved human participants and were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Wesleyan Institutional Review Board and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Cannabis use frequency

Cannabis use frequency was measured by asking participants: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use marijuana or hashish?”

2.2.2 Cannabis age of onset

Onset of cannabis use was measured by asking participants: “How old were you the first time you used marijuana or hashish?”

2.2.3 Cannabis use disorder symptoms

The NSDUH includes items used to assess 8 of the 11 cannabis use disorder symptoms from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These include use in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended (larger/longer), repeated failed efforts to discontinue or reduce the amount that is used (cut down), an inordinate amount of time is occupied acquiring, using, or recovering from the effects (time), continued use despite adverse consequences from its use, such as criminal charges, ultimatums of abandonment from spouse/partner/friends, and poor productivity (continued use), other important activities in life, such as work, school, hygiene, and responsibility to family and friends are superseded by the desire to use (important activities), use in contexts that are potentially dangerous (danger), use despite awareness of physical or psychological problems attributed to use (health) and need for progressively larger amounts to obtain the psychoactive effect experienced when use first commenced, or, noticeably reduced effect of use of the same amount (tolerance). The criteria were evaluated such that a positive response to the item(s) under a given criterion was coded positively as endorsing the symptom. Final variables included binary items for each symptom and a total symptom count. The survey did not include items for cannabis withdrawal, craving or significant impairment of functioning and distress (Appendix A1). Phi coefficients estimating the degree of association between the cannabis use disorder symptoms ranged from .06 to .41. The strongest associations were found between continued use and important activities (.34), health and important activities (.35) larger/longer and cut down (.35), and between tolerance and time (.41).

2.2.4 Cigarette frequency

Cigarette frequency was measured by asking participants: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke part or all of a cigarette?”

2.2.5 Cigarette quantity

Cigarette quantity was measured with the question: “On the days you smoked cigarettes during the past 30 days, how many cigarettes did you smoke per day, on average?”

2.2.6 Recency of cannabis initiation

Recency of cannabis initiation was calculated by subtracting the age at which participants first used marijuana from their current age, and dichotomizing into one year or less vs. two or more years.

2.2.7 Cigarette smoking age of onset

Onset of cigarette use was measured by asking participants: “How old were you the first time you smoked a cigarette?”

2.2.8 Use of other tobacco

Use of other tobacco was measured by asking participants: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use snuff,” “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use chewing tobacco,” and “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you smoke part or all of a cigar?” The variable was coded positively if they reported having used snuff, chewing tobacco, or cigars, at least once during the past 30 days.

2.2.9 Nicotine dependence

In the NSDUH, nicotine dependence was assessed using the 19 item nicotine dependence syndrome scale (NDSS; Shiffman et al., 2004). Participants were asked to rate how true each of the symptoms was of their smoking during the past 30 days. Items were rated using the following response options: (1) not at all true, (2) sometimes true, (3) moderately true, (4) very true, and (5) extremely true. The NDSS provides a single summary score for overall nicotine dependence that includes items measuring drive (i.e., craving and withdrawal symptoms), tolerance (i.e., reduced sensitivity to tobacco products), priority (i.e., preference for smoking over other reinforcers), continuity (i.e., regularity of smoking), and stereotypy (i.e., the “sameness” of smoking contexts). The NDSS has been shown to have good psychometric properties in both adolescent (Clark et al., 2005) and adult populations (Shiffman and Sayette, 2005; Shiffman et al., 2004) and has been found to predict future smoking (Sledjeski et al., 2007). Due to considerable missing data from an option allowing participants to skip two of the items measuring stereotypy and priority regarding nonsmoking friends (“Do you have any friends who do not smoke cigarettes?” and “There are times when you choose not to be around your friends who don’t smoke, because they won’t like it if you smoke”, respectively), these items were excluded from the analysis. The NDSS score was calculated as the sum score of the remaining 17 items.

2.2.10 Alcohol use

Alcohol use frequency was measured by asking participants: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage?”

2.2.11 Other illicit drug use

Other illicit drug use was measured by asking participants if they have had any past-year use of illicit substances other than cannabis (hallucinogens, heroin, cocaine, inhalants, and psychotherapeutics). The variable was coded positively if they replied yes to having used any of the other illicit substances.

2.2.12 Socio-demographic characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics included age, gender, and race/ethnicity (categorized into binary variables, White, Black, and Hispanic/Latino with other as the reference group).

2.3 Analyses

Logistic regression analyses were conducted on the full sample on those who reported using cannabis and smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days to evaluate the association between cigarette smoking, nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorder symptoms after controlling for current cannabis use frequency (number of days used in the past 30), socio-demographic characteristics, onset age of both cigarette smoking and cannabis use, other tobacco use, past month alcohol use, past year illicit substance use, and survey year. All analyses used appropriate sample weights to correct for the differences in the probability of selection, and adjusted for survey design effects to obtain accurate standard errors via SAS (Version 9.4) survey procedures.

Varying coefficient models (VCMs) were also estimated among those who used cannabis and smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days to examine the relationship between nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorder symptoms and how the relationship varies in strength across the full range of current cannabis use frequency. VCMs were run using a publicly available SAS macro (The Methodology Center, 2015), version 3.1.0, developed for analyzing time-varying effects of intensive longitudinal data. VCMs are regression-based models that examine moderation continuously across a variable without imposing strong parametric assumptions about the shape of the nature of the change (e.g., specifying that the coefficient varies in a linear or quadratic manner across the range of the moderating variable) (Tan et al., 2012). Instead, the curve is estimated empirically using spline methods, by fitting a lower-order polynomial curve within each interval based on the user-specified number of knots. This VCM macro produces coefficient estimates along the range of the moderating variable, along with corresponding 95% confidence bands.

Individual cannabis use disorder symptoms (binary) and number of cannabis use disorder symptoms (quantitative) are the main outcome variables and smoking quantity and frequency and nicotine dependence (NDSS score) are the main predictor variables. Using past month cannabis use frequency as the varying-effect, we examined the relationship between nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorder symptoms across the range of frequency of cannabis use, controlling for smoking quantity and frequency and all remaining covariates. This model allows us to examine whether the effects of nicotine dependence on the presence of cannabis use disorder symptoms exist above and beyond exposure to either substance (cigarette smoking and cannabis use) and whether the associations found are consistent based on how frequently cannabis is used.

Separate VCMs were run to examine moderation along the range of cannabis use frequency (i.e., the number of days used cannabis in past month rather than time). These “cannabis frequency varying effects” were interpreted with respect to whether the 95% confidence band is different from 0 (conservatively indicating a statistically significant coefficient), and whether the confidence bands overlap with the band for another point estimate (non-overlapping bands conservatively indicate a significant change in the coefficient), across different values of cannabis use frequency. Before combining the cohorts, we conducted VCM to examine potential study year effects (Appendix B2) and controlled for study year in each of the final regression and TVEM models. All VCMs were run with P-spline estimation and 10 knots. These analyses were followed by additional VCMs stratified by age, gender, ethnicity and recency of cannabis initiation.

3. Results

The average age of onset for cannabis use in this sample of current cannabis users age 12 to 21 is 14.7 years (SE=0.02). Participants consumed cannabis on average 13.0 days out of the past 30 days (SE=0.11, range 1–30), and 158.7 days out of the past 365 days (SE=1.26, range 1–365). The most common cannabis use disorder symptoms were tolerance (43.5% SE 0.51) and time (57.8% SE 0.52). The other cannabis use disorder symptoms were somewhat less prevalent: important activities (13.6% SE 0.33), health (9.0% SE 0.32), continued use (8.9% SE 0.24), larger/longer (8.6% SE 0.26), danger (8.2% SE 0.24), and cut down (7.1% SE 0.27). A total of 53.6% (SE 0.64) reported two or more cannabis use disorder symptoms, the number of symptoms required for a diagnosis of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder.

Over half of the sample also smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days (54.7% SE 0.48), with 20.2% (SE 0.45) reporting smoking cigarettes daily. Participants who also smoked cigarettes started using cannabis at a younger age (14.4 years, SE 0.03 vs. 15.1 years, SE 0.03), used cannabis more frequently (18.6 days in the past 30, SE 0.02 vs. 10.0 days in the past 30, SE 0.14), and reported a higher average number of cannabis use disorder symptoms (1.8 SE 0.02 vs. 1.2 SE 0.02) compared to those who did not smoke cigarettes. Other substance use was also prevalent in this sample including reports of alcohol use an average of 5.5 days out of the past 30 days (SE=0.08, range 0–30) and nearly half of sample (45.8% SE 0.69) reporting other illicit drug use, besides cannabis, during the last year.

Next, the sample was subset to those participants who used cannabis and smoked cigarettes in the past month in order to evaluate the additional contribution of nicotine dependence symptoms in predicting cannabis use disorder symptoms both individually and as total number of cannabis symptoms endorsed. Logistic regression results are presented in Table 1 and 2. In each model, the nicotine dependence symptom score was significantly and positively associated with the probability of endorsing individual cannabis use disorder symptoms and with the total number of cannabis symptoms endorsed, after controlling for frequency of cannabis use, cannabis age of onset, smoking quantity and frequency, cigarette smoking age of onset, other tobacco use, alcohol use, illicit drug use, socio-demographic characteristics and study year. For larger/longer, cut down, time, and health symptoms, cigarette smoking quantity and frequency were negatively associated with each above symptom, showing that more frequent cigarette smoking and larger numbers of cigarettes smoked predicted a lower likelihood of symptom endorsement. Cigarette smoking frequency but not smoking quantity, was negatively associated with continued use, important activities, danger, and tolerance symptoms. A multiple regression model predicting number of cannabis use symptoms confirmed these symptom level results. Nicotine dependence symptoms (Beta 0.03, p < .0001) were positively associated with number of cannabis symptoms over and above measures of both smoking and cannabis use behaviors. Cigarette smoking quantity (Beta −0.01, p < .0001) and frequency (Beta −0.02, p < .0001) were both negatively associated with the number of cannabis use symptoms. When examining covariates across each model, other illicit drug use was also found to consistently and significantly predict cannabis use symptoms.

Table 1.

Logistic regression for cannabis use disorder symptoms. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals

| Larger/Longer (9.5% SE 0.41) n=11,387 |

Cut down (7.8% SE 0.36) n=11,390 |

Time (67.2% SE 0.59) n=11,397 |

Continued use (10.6% SE 0.36) n=11,393 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day cannabis frequency | 1.04 (1.03–1.05)** | 1.05 (1.04–1.06)** | 1.11 (1.10–1.12)** | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)** |

|

| ||||

| Cannabis age of onset | 1.02 (0.97–1.08) | 1.06 (1.02–1.11)* | 0.91 (0.88–0.95)** | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) |

|

| ||||

| Nicotine dependence symptom score (NDSS) | 1.03 (1.02–1.03)** | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)** | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)** | 1.03 (1.02–.1.04)** |

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day cigarette frequency | 0.98 (0.97–0.99)* | 0.97 (0.96–0.98)** | 0.98 (0.97–0.99)** | 0.97 (0.96–0.98)** |

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day cigarette quantity | 0.98 (0.96–1.00) | 0.97 (0.96–0.99)* | 0.98 (0.97–0.99)* | 0.98 (0.97–1.03) |

|

| ||||

| Cigarette smoking age of onset | 1.02 (0.97–1.07) | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.98 (0.95–1.03) |

|

| ||||

| Other tobacco use | 1.09 (0.90–1.33) | 1.07 (0.87–1.31) | 1.12 (0.97–1.29) | 1.36 (1.11–1.67)* |

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day alcohol frequency | 0.97 (0.95–0.98)** | 0.98 (0.97–0.99)* | 0.98 (0.97–0.99)* | 0.98 (0.97–0.99)* |

|

| ||||

| Past year illicit substance use (other than cannabis) | 1.33 (1.11–1.60)* | 1.52 (1.23–1.87)** | 1.66 (1.46–1.89)** | 1.73 (1.40–2.14)** |

|

| ||||

| Age | 1.08 (1.02–1.14)* | 1.05 (0.99–1.12) | 0.95 (0.92–0.98)* | 0.80 (0.77–0.84)** |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male vs. Female | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 0.97 (0.77–1.24) | 0.84 (0.73–0.97)* | 0.84 (0.67–1.05) |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White vs. non-White | 0.65 (0.47–0.91)* | 0.90 (0.61–1.32) | 0.98 (0.76–1.23) | 0.85 (0.55–1.33) |

| Black vs. non-Black | 1.22 (0.79–1.91) | 1.79 (1.12–2.85)* | 0.90 (0.64–1.29) | 1.28 (0.73–2.24) |

| Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic | 0.92 (0.62–1.37) | 1.37 (0.89–2.11) | 1.19 (0.91–1.57) | 1.21 (0.75–1.97) |

|

| ||||

| Survey year | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 1.02 (0.98–1.07) | 1.0 (0.98–1.04) | 1.0 (0.95–1.05) |

p < .05,

p < .001

Table 2.

Logistic regression for cannabis use disorder symptoms. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals

| Important Activities (16.3% SE 0.53) n=11,400 |

Danger (10.2% SE 0.34) n=11,394 |

Health (10.2% SE 0.44) n=11,395 |

Tolerance (50.7% SE 0.64) n=11,396 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day cannabis frequency | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)** | 1.01 (1.001–1.02)* | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)** | 1.06 (1.05–1.07)** |

|

| ||||

| Cannabis age of onset | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) |

|

| ||||

| Nicotine dependence symptom score (NDSS) | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)** | 1.02 (1.01–1.03)** | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)** | 1.03 (1.02–1.04)** |

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day cigarette frequency | 0.97 (0.96–0.98)** | 0.97 (0.96–0.99)** | 0.97 (0.96–0.98)** | 0.976 (0.969–0.98)** |

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day cigarette quantity | 0.98 (0.97–1.01) | 1.0 (0.98–1.01) | 0.97 (0.96–0.99)* | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) |

|

| ||||

| Cigarette smoking age of onset | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) |

|

| ||||

| Other tobacco use | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | 1.26 (1.08–1.47)* | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) | 1.12 (1.01–1.24)* |

|

| ||||

| Past 30 day alcohol frequency | 1.0 (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 (1.002–1.03)* | 1.0 (0.98–1.01) | 0.99 (0.99–1.002) |

|

| ||||

| Past year illicit substance use (other than cannabis) | 1.63 (1.42–1.87)** | 1.44 (1.19–1.76)** | 1.3 (1.08–1.57)* | 1.48 (1.32–1.65)** |

|

| ||||

| Age | 0.92 (0.88–0.96)** | 0.82 (0.78–0.87)** | 0.95 (0.90–1.01) | 0.92 (0.89–0.95)** |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male vs. Female | 0.89 (0.77–1.02) | 0.83 (0.69–0.99)* | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | 0.83 (0.75–0.93)** |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White vs. non-White | 0.71 (0.52–0.96)* | 1.09 (0.79–1.48) | 0.77 (0.55–1.09) | 0.69 (0.55–0.88)* |

| Black vs. non-Black | 1.03 (0.68–1.54) | 1.1 (0.75–1.74) | 1.02 (0.67–1.57) | 0.71 (0.53–0.93)* |

| Hispanic vs. non-Hispanic | 1.07 (0.79–1.45) | 1.22 (0.83–1.79) | 0.89 (0.60–1.31) | 0.90 (0.69–1.19) |

|

| ||||

| Survey year | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 0.99 (0.95–1.05) | 0.99 (0.96–1.04) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) |

p < .05,

p < .001

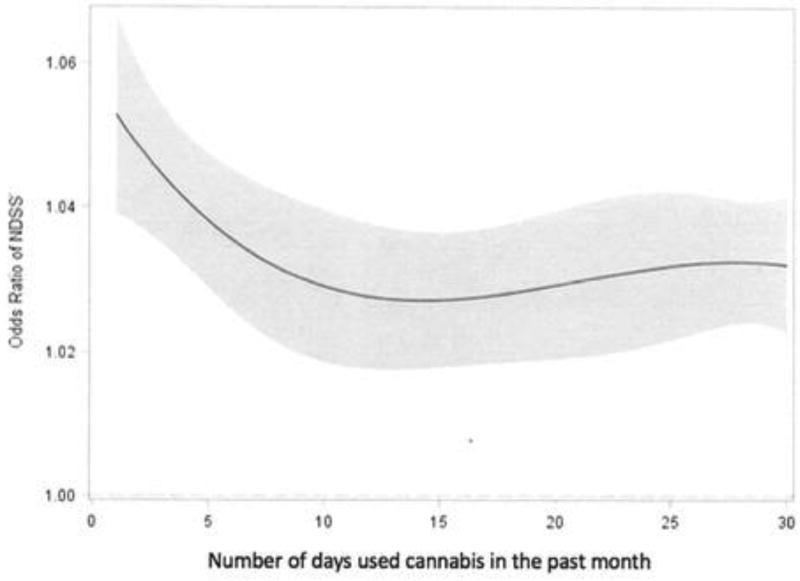

VCMs revealed that the strength of the relationship between nicotine dependence symptom scores and cannabis use disorder symptoms varied as a function of frequency of cannabis use from 1 day used in the past month to daily use of cannabis. In each model, the strength of the association between nicotine dependence scores and cannabis use symptoms was stronger with less frequent cannabis use and still significant, but weaker with more frequent use. Figure 1 illustrates this pattern of findings for total number of cannabis use symptoms endorsed by showing significant regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals across the range of cannabis user frequency. The relationship between nicotine dependence scores and the total number of cannabis symptoms endorsed is significantly stronger for those using cannabis 1 to 5 days compared to those using 25 to 30 days in the past month. This pattern was also seen when predicting the cannabis tolerance symptom.

Figure 1.

Coefficient curve and 95% confidence band for covariate: NDSS. Effect of nicotine dependence scores (NDSS) on total number of cannabis symptoms endorsed by cannabis use frequency in the past month (regression coefficient and 95% confidence band.

For the cut down (Figure 2) and continued use (Figure 3) symptoms, nicotine dependence scores were more strongly associated for those using cannabis between 1 and 25 days in the past month, while showing a significant but weaker relationship for those using cannabis daily or near daily. For the remaining cannabis use disorder symptoms, a trend toward stronger relationships between nicotine dependence scores and cannabis use disorder symptoms was seen for those using cannabis less frequently compared to more frequently, but the 95% confidence intervals overlapped, suggesting that these differences did not reach statistical significance. All VCMs were adjusted for cigarette smoking quantity and frequency, age of onset of cigarette smoking and cannabis use, other tobacco use, alcohol, other illicit drug use, socio-demographic characteristics and study year. No differences in the strength of the association between nicotine dependence symptoms and cannabis use symptoms across the range of cannabis use frequency were found when considering age, gender, ethnicity and recency of cannabis initiation (1 year or less vs. 2 or more years previous). That is, for each potential moderator, confidence intervals were found to be overlapping.

Figure 2.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence band for covariate: NDSS. Effect of nicotine dependence scores (NDSS) on repeated failed efforts to discontinue or reduce the amount of cannabis that is used - cut down (Odds ratio and 95% confidence band).

Figure 3.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence band for covariate: NDSS. Effect of nicotine dependence scores (NDSS) on continued use despite problems with family or friends by cannabis use frequency in the past month (Odds ratio and 95% confidence band).

4. Discussion

The present study examined whether cigarette smoking and/or nicotine dependence best predicts cannabis use disorder symptoms among adolescents and young adults and whether these relationships differ based on the frequency of cannabis use. Several major findings emerged. First, over half of the current cannabis users in the sample also reported smoking cigarettes. Participants started using cannabis at a younger age, used cannabis more frequently, and reported a higher average number of cannabis use disorder symptoms compared to those who did not smoke cigarettes. Second, nicotine dependence symptoms were positively and significantly associated with the probability of endorsing individual cannabis use disorder symptoms and with a greater number of cannabis symptoms endorsed, over and above exposure to either cannabis or tobacco. In contrast, among those reporting cannabis use and cigarettes smoking in the past 30 days, cigarette smoking quantity and/or frequency were negatively associated with cannabis use disorder symptoms. VCMs further revealed that the strength of the association between nicotine dependence symptom scores and cannabis use disorder symptoms was stronger with less frequent cannabis use and still significant but weaker among those reporting more frequent use.

These findings add to the extant literature suggesting that cigarette smokers are vulnerable to substance use disorder symptoms associated with cannabis use (Agrawal and Lynskey, 2009; Fairman, 2015; Ream et al., 2008). Though descriptive results in the present study showed that cannabis users reported a larger number of cannabis use symptoms in the context of cigarette smoking, when examining adolescents and young adults who reported use of both substances in the past 30 days, it was nicotine dependence symptoms and not smoking quantity or frequency that was positively and significantly associated with cannabis use disorder symptoms.

The link between cigarette smoking and cannabis use has often been discussed in terms of the role of each behavior in increasing risk of exposure to the other substance, particularly in the form of blunts (Peters et al., 2016) and/or opportunity and availability to use both substances (Wagner et al., 2005). The present findings suggest that nicotine dependence symptoms likely serve as a signal for enhanced sensitivity to cannabis use disorder symptoms, independent of level of substance use exposure that included not only cigarette smoking and cannabis use, but also other tobacco use, alcohol use and other illicit substance use. One explanation is that each substance may increase the rewarding effects of the other. For example, in mice, co-administration of sub-threshold doses of THC and nicotine induced rewarding effects (Valjent et al., 2002) and acute THC administration significantly decreased the incidence of several precipitated nicotine withdrawal signs and ameliorated the aversive motivational consequences of nicotine withdrawal (Balerio et al., 2006). Based on survey data, young adults reported using both tobacco and cannabis because cigarettes smoking helped reduce cannabis urges (Ramo et al., 2013). Alternately, a third variable may be related to risk for both cannabis use disorder symptoms and nicotine dependence. For example, a recent study examining common genetic variants on alcohol, tobacco, cannabis and illicit drug dependence found that common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) explained 25–36% of the variance across measures of dependence (Palmer et al., 2015). It is also possible that at low levels of cannabis use, both cannabis use disorder symptoms and nicotine dependence are being experienced only by individuals most sensitive to their development, compared to higher levels of use, when the development of these symptoms is more common. This interpretation would suggest that cross-over effects may be most pronounced not for lower levels of use per se, but for individuals most sensitive to substance use disorder symptoms. Future longitudinal, prospective work focused on whether these effects of transient or permanent within subject is needed to support or refute this hypothesis.

The counter-intuitive finding that infrequent cigarette smoking and/or lower smoking quantity significantly predicted cannabis use disorder symptoms might be explained in part by our VCM results showing that the association between nicotine and cannabis use symptoms is stronger for those who use cannabis less frequently. This finding confirms previous literature focused on tobacco and alcohol co-use. In one study, past year smokers were found to be at elevated risk for alcohol use disorders when compared to never smokers who drank equivalent quantities, with these effects being most pronounced at lower levels of drinking (Grucza and Bierut, 2006). Similarly, adults with alcohol dependence have been showed to have elevated risk of nicotine dependence at low to moderate levels of smoking, while no difference in risk for nicotine dependence was observed between alcohol-dependent and nondependent individuals smoking more than a pack a day (Dierker and Donny, 2008).

Taken together, these findings add to the growing body of evidence showing substantial individual variability in symptoms associated with one type of substance use based on symptoms of a second type of substance use, not accounted for by exposure to either substance (Dierker and Donny, 2008; Dierker et al., 2011; Dierker et al., 2013; Dierker et al., 2016). Notably, though past year use of other illicit substances did not confound these relationships, the fact that it was found to positively and independently predict endorsement of each cannabis use disorder symptom over and above cannabis use and nicotine dependence symptoms suggests that it is possible that substance use disorder symptoms associated with the emergence of cannabis use may also be influenced by symptoms associated with other types of substance use beyond tobacco. Given that the association between illicit substance use and cannabis use disorder symptoms was stronger than the association between nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorder symptoms, future research with adequate measures of substance use disorder symptoms for a range of illicit substances is needed to disentangle the exposure-symptom links that may help to elucidate developmental mechanisms.

Socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and ethnicity have previously been shown to be associated with different levels of susceptibility to cigarette smoking and cannabis use and their associated symptoms. For example, the risk for tobacco use and cannabis use disorders has been shown to be higher among males than females (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015; von Sydow et al., 2001). In addition, ethnic minority groups tend to have lower rates of cigarette smoking, but higher rates of cannabis use compared to Whites, and higher rates of past year cannabis dependence among those who use cannabis (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2015; Wu et al., 2016). Though the present sample of current cannabis users was nearly 60% male, no differences were found in the strength of the association between nicotine dependence symptoms and cannabis use disorder symptoms when considering age, gender, ethnicity or recency of cannabis initiation, regardless of the frequency of cannabis use.

A major strength of this study is that it involved a large, nationally representative sample that allowed for an examination of cigarette smoking, cannabis use and their associated symptoms in a way that generalizes to a broad population of adolescent and young adult cannabis users in the U.S. The sample size also allowed us to evaluate whether reported results were consistent across frequency of cannabis use and by age, gender, ethnicity and recency of cannabis initiation. We were also able to control for important covariates related to other substance use, and socio-demographic characteristics. Notably, these findings are among the first to characterize the relationship between nicotine dependence and cannabis use disorder symptoms across the continuum of cannabis use frequency and after controlling for cigarette smoking quantity and frequency. If causally associated, these findings would suggest that a reduction of nicotine dependence may prevent or reduce symptoms associated with cannabis use. If instead, nicotine dependence symptoms are a signal of sensitivity for symptoms associated with cannabis use, best accounted for by a third variable, then adolescents and young adults with measurable symptoms associated with either cigarette smoking or cannabis use, regardless of their level of use, represent an important subgroup that may benefit from intervention.

Despite these strengths, there are also several weaknesses that should be noted. First, though we examined cannabis use frequency in the past 30 days as the primary measure of cannabis exposure, an important limitation of the present study is our inability to also consider the quantity of cannabis use and mode of administration, or the amount of co-use in the form of blunts. Though frequency of use is a particularly salient measure in that increasing frequency, rather than infrequent high quantity use, is believed to play a larger role in the development of substance use symptoms in that greater abuse and dependence is manifested by increasingly shorter periods between exposures (Koob and Volkow, 2010), frequency remains a markedly incomplete measure of exposure. Further, NSDUH does not measure all cannabis use symptoms as defined by the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (Version 5), making prevalence of a diagnosable disorder difficult to estimate. Finally, it is important to note that the coefficient functions in VCMs cannot be interpreted as representing causal associations.

Similarly, these results are directly tied to the measurement of nicotine dependence according to the NDSS and cannabis use disorder symptoms more closely linked to DSM-V measurement; as such, we could not directly assess the cross-over effects of individual symptoms. With regard to DSM-5 cannabis use disorder symptoms, withdrawal, craving and significant impairment of functioning were not measured. Further, though we considered both cigarette smoking and other tobacco use in our models, data on the use of e-cigarettes, a form of nicotine administration that is becoming more prevalent among adolescents (Singh et al., 2016), was not available. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the data cannot inform the direction of the relationship between cannabis/tobacco exposure and associated symptoms. Future longitudinal research that asks newly incident substance users to give month-by-month reports of frequency of use and occurrence of clinical features might help to avoid these inherent limitations of cross-sectional data (Vsevolozhskaya and Anthony, 2017).

This study identified important differences in the likelihood of experiencing cannabis use disorder symptoms according to an individual’s level of nicotine dependence symptoms among adolescents and young adults who reported both smoking cigarettes and using cannabis in the past 30 days. This relationship was found to be significant across the continuum of cannabis use, ranging from infrequent use (1 day per month) to daily use. While there is some debate about the nature and prevalence of health risks of cannabis use, for adolescent and young adult cannabis users who also smoke cigarettes, what might appear to be benign experimentation with cannabis may put them at much greater risk for developing abuse and dependence symptoms. The present findings suggest that nicotine dependence may play a role in the experience of cannabis use disorder symptoms as either a cause and/or signal of sensitivity regardless of level of cannabis use. If causally associated, these findings would suggest that tobacco control may prevent or reduce the early emergence of cannabis use disorder symptoms among cannabis users. If instead, however, nicotine dependence is a signal for cannabis use disorder symptoms, best accounted for by a third variable, then adolescents and young adult cannabis users who also smoke represent an important subgroup that may benefit from intervention that directly targets this association

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examine cannabis use disorder symptoms and nicotine dependence.

Cigarette use was associated with cannabis use and cannabis use disorder symptoms.

Nicotine dependence was associated with each cannabis use disorder symptom.

This effect remained after controlling for smoking and cannabis use.

This was effect was significant across all levels of cannabis use.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Preparation of this paper was funded by Awards R01-DA039854 and P50 DA039838 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse awarded to the Methodology Center, Penn State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:…

Contributors

Lisa Dierker designed the analytic plan, contributed to drafting the initial manuscript, conducted the final analyses, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Jennifer Rose assisted with the analyses, contributed to drafting the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. Jessica Braymiller, Renee Goodwin and Arielle Selya reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Conflict of Interest

Each author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey M. Tobacco and cannabis co-occurence: Does route of administration matter? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amos A, Wiltshire S, Bostock Y, Haw S, McNeill A. You can't go without a fag… you need it for your hash'- a qualitative exploration of smoking, cannabis and young people. Addiction. 2004;99:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badiani A, Boden JM, De Pirro S, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Harold GT. Tobacco smoking and cannabis use in a longitudinal birth cohort: Evidence of reciprocal causal relationships. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;150:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balerio GN, Aso E, Maldonado R. Role of the cannabinoid system in the effects induced by nicotine on anxiety-like behaviour in mice. Psychopharmacol. 2006;184:504–513. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beenstock M, Rahav G. Testing Gateway Theory: Do cigarette prices affect illicit drug use? Health Econ. 2002;21:679–698. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Newcomb MD, Zimmerman MA. Cigarette use and drug use progression: Growth trajectory and lagged effect hypotheses. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of drug involvement. 2002. pp. 223–253. [Google Scholar]

- Clark D, Wood D, Martin C, Cornelius J, Lynch K, Shiffman S. Multidimensional assessment of nicotine dependence in adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton W, Han B, Jones C, Blanco C, Hughes A. Cannabis use and use disorders in adults in the USA, 2002-14: analysis of annual cross-sectional surveys. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;310:954–964. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico E, McCarthy D. Initiation and escalation of younger adolescents' substance use: The impact of perceived peer use. Adolesc. Health. 2006;394:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. The relationship between cannabis use and other substance use in the general population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;64:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Donny E. The role of psychiatric disorders in the relationship between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among young adults. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2008;103:439–446. doi: 10.1080/14622200801901898. doi: http://doi.org/10.1080/14622200801901898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Mendoza W, Goodwin RD, Selya A, Rose J. Cannabis use disorder symptoms among recent onset cannabis users. Addict. Behav. 2017;68:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Rose JS, Donny E, Tiffany S. Alcohol use as a signal for sensitivity to nicotine dependence among recent onset smoker. Addict. Behav. 2011;364:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.010. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Selya A, Piasecki T, Rose J, Mermelstein R. Alcohol problems as a signal for sensitivity to nicotine dependence and future smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;1326:688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierker L, Selya A, Rose J, Hedeker D, Mermelstein R. Nicotine dependence and alcohol problems from adolescence to young adulthood. Dual Diagnosis. 2016;12:9. doi: 10.21767/2472-5048.100009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairman BJ. Cannabis problem experiences among users of the tobacco-cannabis combination known as blunts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;150:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades K, Boyle MH. Adolescent tobacco and cannabis use: Young adult outcomes from the Ontario Child Health Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2007;48:724–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber SA, Sagar KA, Dahlgren MK, Racine M, Lukas SE. Age of onset of marijuana use and executive function. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2012;26:496–506. doi: 10.1037/a0026269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grucza R, Bierut L. Cigarette smoking and the risk for alcohol use disorders among adolescent drinkers. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2006;3012:2046–2054. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Bedi G, Cooper ZD, Glass A, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Foltin RW. Predictors of cannabis relapse in the human laboratory: Robust impact of tobacco cigarette smoking status. Biol. Psychiatry. 2013;733:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.028. doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highet G. The role of cannabis in supporting young people's cigarette smoking: A qualitative exploration. Health Educ. Res. 2004;196:635–643. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huizink AC, Levälahti E, Korhonen T, Dick DM, Pulkkinen L, Rose RJ, Kaprio J. Tobacco, cannabis, and other illicit drug use among Finnish adolescent twins: Causal relationship or correlated liabilities? J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2010;711:5–14. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L, O’Malley P, Miech R, Bachman J, Schulenberg J. Monitoring the Future National Survey results on drug use: Overview: key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2016. Retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org//pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2016.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kapusta N, Plener P, Schmid R, Thau K, Walter H, Lesch O. Multiple substance use among young males. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2007;86:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob G, Volkow N. Neurocirciutry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai S, Lai H, Page JB, McCoy CB. The association between cigarettes smoking and drug abuse in the United States. J. Addict. Diseases. 2000;194:11–24. doi: 10.1300/J069v19n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mewton L, Teesson M, Slade T. “Youthful epidemic” or diagnostic bias? Differential item functioning of DSM-IV cannabis use criteria in an Australian general population survey. Addict. Behav. 2010;35:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokrysz C, Gage S, Landy R, Munafo M, Roiser J, Curran H. Neuropsychological and educational outcomes related to adolescent cannabis use, a prospective cohort study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24:695–696. [Google Scholar]

- Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, Blakemore C. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007;369:1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer R, Brick L, Nugent N, Bidwell L, McGeary J, Knopik V, Keller M. Examining the role of common genetic variants on alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and illicit drug dependence. Addiction. 2015;1103:530–537. doi: 10.1111/add.12815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton G, Coffey C, Carlin J, Sawyer S, Lynskey M. Reverse gateways? Frequent cannabis use as a predictor of tobacco initiation and nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2005;100:1518–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: A systematic review. Addiction. 2012;1078:1404–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters EN, Schauer G, Rosenberry Z, Pickworth W. Does cannabis “blunt” smoking contribute to nicotine exposure?: Preliminary product testing of nicotine content in wrappers of cigars commonly used for blunt smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:11. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.007. doi: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo D, Liu H, Prochaska J. Validity and reliability of the nicotine and cannabis interaction expectancy NAMIE questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013:1311–2. 166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Delucchi KL, Hall SM, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Cannabis and tobacco co-use in young adults: Patterns and thoughts about use. J. Stud./ Alcohol Drugs. 2013;742:301–331. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ream G, Benoit E, Johnson B, Dunlap E. Smoking tobacco along with cannabis increases symptoms of cannabis dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;953:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Ayette MA. Validation of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale NDSS: A criterion-group design contrasting chippers and regular smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ, Hickcox M. The Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale: A multidimensional measure of nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2004;6:327–348. doi: 10.1080/1462220042000202481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Arrazola R, Corey C, Husten M, Neff L, Homa D, King B. Tobacco use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2016;65:361–367. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6514a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledjeski E, Dierker L, Costello D, Shiffman S, Donny E, Flay B. Predictive validity of four nicotine dependence measures in a college sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiby AI, Hickman M, Munafò MR, Heron J, Yip VL, Macleod J. Adolescent cannabis and tobacco use and educational outcomes at age 16: Birth cohort study. Addiction. 2015;110:658–668. doi: 10.1111/add.12827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.html. [PubMed]

- Tan X, Shiyko MP, Li R, Li Y, Dierker L. A time-varying effect model for intensive longitudinal data. Psych. Methods. 2012;171:61–77. doi: 10.1037/a0025814. doi: http://doi.org/10.1037/a0025814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Methodology Center. TVEM SAS Macro Suite Version 3.1.0 [Software] University Park: The Methodology Center, Penn State; 2015. Retrieved from http://methodology.psu.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Tullis L, Dupont R, Frost-Pineda K, Gold M. Cannabis and tobacco: A major connection? J. Addict. Diseases. 2003;22:51–62. doi: 10.1300/J069v22n03_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Mitchell JM, Besson MJ, Caboche J, Maldonado R. Behavioural and biochemical evidence for interactions between delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and nicotine. Pharmacol. 2002;135:564–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Sydow K, Lieb R, Pfister H, Höfler M, Sonntag H, Wittchen H-U. The natural course of cannabis use, abuse and dependence over four years: A longitudinal community study of adolescents and young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;643:347–361. doi: 10.1016/S0376-87160100137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vsevolozhskaya O, Anthony J. Estimated probability of becoming a case of drug dependence in relation to duration of drug-taking experience: A functional analysis approach. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2017;26 doi: 10.1002/mpr.1513. [Epub.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. From first drug use to drug dependence: Developmental periods of risk for dependence upon cannabis, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;26:479–488. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Velasco-Mondragón HE, Herrera-Vázquez M, Borges G, Lazcano-Ponce E. Early alcohol or tobacco onset and transition to other drug use among students in the State of Morelos, Mexico. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;771:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.009. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger A, Platt J, EsanGalea S, Erlich D, Goodwin R. Cigarette sying is associated with increased risk of substance use disorder relapse: A nationally representative, prospective longitudinal investigation. Clin. Psychiatry. 2017;782:152–160. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L-T, Zhu H, Swartz MS. Trends in cannabis use disorders among racial/ethnic population groups in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:181–190. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.002. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.