Abstracts

Background

The magnitude effects of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatching on post-transplant outcomes of kidney transplantation remain controversial. We aim to quantitatively assess the associations of HLA mismatching with graft survival and mortality in adult kidney transplantation.

Methods

We searched PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library from their inception to December, 2016. Priori clinical outcomes were overall graft failure, death-censored graft failure and all-cause mortality.

Results

A total of 23 cohort studies covering 486,608 recipients were selected. HLA per mismatch was significant associated with increased risks of overall graft failure (hazard ratio (HR), 1.06; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.05–1.07), death-censored graft failure (HR: 1.09; 95% CI 1.06–1.12) and all-cause mortality (HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07). Besides, HLA-DR mismatches were significant associated with worse overall graft survival (HR: 1.12, 95% CI: 1.05–1.21). For HLA-A locus, the association was insignificant (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.98–1.14). We observed no significant association between HLA-B locus and overall graft failure (HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.90–1.15). In subgroup analyses, we found recipient sample size and ethnicity maybe the potential sources of heterogeneity.

Conclusions

HLA mismatching was still a critical prognostic factor that affects graft and recipient survival. HLA-DR mismatching has a substantial impact on recipient’s graft survival. HLA-A mismatching has minor but insignificant impact on graft survival outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12882-018-0908-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Human leukocyte antigen, Kidney transplantation, Graft survival, Mortality, Meta-analysis

Background

Compared with dialysis, renal transplantation is a more preferred option for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [1]. In recent report of global database on donation and transplantation (http://www.transplant-observatory.org), about 80,000 renal transplants were performed annually [2]. However, in 2016 United States Renal Data System (USRDS) Annual Data Report, the long-term survival benefit remained unsatisfactory, with ten-year graft survival probabilities of 46.9% for deceased donor transplant [3].

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) was important biological barrier to a successful transplantation and has substantial impact on the prolongation of graft survival [4]. However, the emergency of modern immunosuppressive agents minimized the effect of HLA compatibility. The US kidney allocation system was extensively modified to eliminated HLA-A similarity in 1995 [5] and HLA-B similarity in 2003 [6]. In the revised United Kingdom kidney allocation scheme, HLA-A matching is no longer considered [7]. But the latest European Renal Best Practice Transplantation Guidelines still recommended that matching of HLA-A, -B, and -DR whenever possible, while gave more weight to HLA-DR locus [8]. So far, the current kidney allocation guideline recommendations were inconsistent in term of HLA compatibility. Besides, for the primary aim to make the kidney last as long as possible, all the current kidney allocation systems were not perfect. Here, we sought to conduct a meta-analysis to assess the magnitude effect of HLA mismatching in adult kidney transplantation, with a particular focus on graft survival and recipient mortality.

Methods

The study was registered in the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42017071894). Details of protocol are described in Additional file 1: Supplemental Methods. The meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) protocol [9] (Additional file 2: Table S1) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline [10] (Additional file 3: Table S2).

Literature search strategy

We searched PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library from their inception to December, 2016, without language restriction. We used the following combinations of Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and corresponding text words: “kidney transplantation”, “renal transplantation”, “human leukocyte antigen”, “HLA” and all possible spellings of “survival”. Further details are described in Additional file 1. Reference lists of articles were manually screened to identify further relevant studies. The literature search was performed independently by two investigators (XMS and XHZ). Differences were resolved by consensus.

Study selection

We included studies that (1) included a study cohort comprising adult post-kidney transplant recipients; (2) were cohort studies/trials reporting associations between HLA mismatching and post-transplant survival outcomes; and (3) provided effect estimates of hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence interval (CIs). Studies reporting data on children or animals or in vitro research were excluded. Besides, reviews, meta-analyses, case reports, case series and technical descriptions with insufficient data or unrelated topics were also excluded. For studies covered overlapping data, we included the most recent and informative one. XMS and XHZ independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Outcome measures

Our primary clinical endpoint was overall graft failure; secondary clinical endpoints were death-censored graft failure and all-cause mortality. The European Renal Best Practice Transplantation Guidelines and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Guidelines was used to evaluate the incidence of measured outcomes [11, 12].

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted from predefined protocol, then recorded in a standardized Excel form, including the first author’s name, publication date, study location, study design, cohort size, recipient age, sex distribution, duration, donor source, data source (multi-centered or single-centered), follow-up, unadjusted and adjusted HRs of overall graft failure, death-censored graft failure and all-cause mortality per HLA-mismatch increased, and adjusted covariates in reported multivariable analysis. We contacted libraries abroad or corresponding author of relevant articles by email when detailed data for pooling analysis was unavailable. The methodological quality of included studies was described using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. High-quality studies were defined by a score of > 5 points [13]. Disagreements in the scores were resolved by consensus between XMS, XHZ and JD.

Statistical analysis

Hazard ratios (HRs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were directly retrieved from each study. We chose HRs as the statistic estimates because they correctly reflect the nature of data and account for censoring. Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistic were applied to assess heterogeneity between studies. The following criteria were used: I2 < 50%, low heterogeneity; 50–75%, moderate heterogeneity and > 75%, high heterogeneity [14, 15]. When significant heterogeneity was found between studies (P < 0.10 or I2 > 50%), the effect estimates were calculated using a random-effects model and the DerSimonian-Laird method [16]; otherwise, a fixed-effects model with the Mantel-Haenszel method was used [17]. Subgroup analyses included recipient sample size (≥10,000 vs < 10,000), the nature of data (univariable-unadjusted vs multivariable-adjusted effect estimates), donor source (deceased vs living and deceased), data source (multi-centered vs single-centered) and geographical locations (Europe, North America, Asia and Oceania). A sensitivity analyses was performed by omitting one study at a time and then reanalyzing the data to assess the change in effect estimates. To further explore heterogeneity, a random-effects univariate meta-regression was conducted when at least 10 studies were available. For outcomes of at least 10 studies included, publication bias was assessed by funnel plot and Egger test [18]. Egger test with two-sided P < 0.10 was considered to be statistically significant. Analyses were performed using STATA software, version 13.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

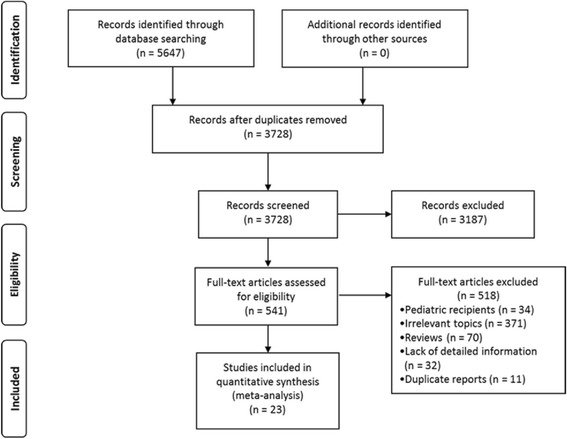

Of 5647 articles identified, we reviewed the full text of 541 reports, and 23 studies [19–41] with 486,608 adult post-transplant recipients were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Detailed characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1. Among these studies, 18 studies provided multivariable-adjusted effect estimates [19, 21–24, 27–39], 3 studies provided both multivariable-adjusted and univariable-unadjusted data [20, 25, 26], and 2 studies provided univariable-unadjusted data [40, 41]. Besides, 8 studies were multi-centered [19, 23, 27, 32, 33, 35, 37, 38]; another 15 studies were single-centered [20–22, 24–26, 28–31, 34, 36, 39–41]. When considering HLA locus as categories, 11 studies reported survival outcomes of all HLA locus (HLA-A, -B and -DR) [20, 23–28, 32, 35, 36, 40], 8 [19, 20, 22, 29–31, 33, 41] reported HLA-DR locus, 4 with HLA-B locus [19, 30, 31, 33], and 3 with HLA-A locus [30, 31, 33]. The methodological quality score was high, ranging from 6 to 8 points (details of quality assessment are provided in Additional file 4: Table S3).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author, year | No. of recipients | Mean age, years | Male, % | Year data collection | Country of origin | Data Source | Type of risk (Adjustments) | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Fijter, 2001 [20] | 496 | 47.4 | 62.1 | 1983–1997 | Netherlands | Single-center | Recipient and donor age and gender, CIT, PRA, initial immunosuppression, DGF, ARE, type of AR | 8 |

| Roodnat, 2003 [21] | 1124 | 44.8 | 58.5 | 1981–2000 | Netherlands | Single-center | Recipient and donor age, donor gender, CIT, donor Cr, transplantation year, donor type, number of previous transplants | 8 |

| Tekin, 2015 [22] | 2633 | 47.7 | 40.4 | 2008–2013 | Turkey | Single-center | Recipient and donor age and gender, donor follow-up Cr levels, time on dialysis, original disease, CIT, DGF, ARE, recipient serum Cr-levels, warm ischemia times | 7 |

| Mandal, 2003 [23] | 31,909 | NR | 59.0 | 1995–1998 | USA | Registry (USRDS) | Recipient and donor age, recipient gender and race, donor type, CIT, diabetic nephropathy | 8 |

| Arias, 2007 [24] | 214 | 47.7 | 64.0 | NR | Spain | Single-center | Recipient and donor age and gender, donor type, ARE, CMV, CIT, PRA, glomerulosclerosis, interstitial fibrosis, tubular atrophy, arteriosclerosis, arteriolar hyalinosis | 8 |

| Cho, 2016 [25] | 229 | 63.2 | 63.6 | 1995–2014 | Korea | Single-center | Recipient and donor age, donor type, recipient gender, ABO-incompatible, DGF, CMV, HBV, HCV, time on dialysis prior to transplantation | 8 |

| Gomez, 2013 [26] | 487 | 38.0 | 63.2 | 1979–1997 | Spain | Single-center | Recipient and donor age, donor gender, donor type, DGF, CIT, PRA, AR, time on dialysis, immunosuppression | 8 |

| Laging, 2012 [28] | 1821 | 47.8 | 62.0 | 1990–2009 | Netherlands | Single-center | Recipient and donor age, maximum PRA, current PRA, transplant year, donor gender, donor type, DGF, immunosuppression | 8 |

| Laging, 2014 [35] | 1998 | 48.2 | 62.5 | 1990–2010 | Netherlands | Single-center | Recipient and donor age, donor gender, donor type, PRA, transplant year, immunosuppression | 8 |

| Schnuelle, 1999 [30] | 152 | 46.4 | 56.7 | 1989–1998 | Germany | Single-center | Recipient and donor age, recipient gender, time on dialysis, original disease, PRA, dopamine, noradrenaline, head trauma, previous transplant, immunosuppression, Induction (ATG/OKT3) | 8 |

| Hariharan, 2002 [32] | 105,742 | NR | NR | 1988–1998 | USA | Registry (OPTN/UNOS) | Recipient and donor age and race, gender, DM, hypertensive nephropathy, pre-TX dialysis and transfusions, previous transplant, most recent PRA, DGF, donor type, 1-year AR, induction therapy, immunosuppression regiment | 7 |

| Massie, 2016 [19] | 106,019 | 50.0 | 62.4 | 2005–2013 | USA | Registry (SRTR) | Recipient and donor age, gender and race, PRA, transplant year, private insurance, HCV, eGFR, BMI, cigarette use, SBP, ABO-incompatible, unrelated to recipient, min(donor/recipient weight ratio,0.9) | 8 |

| Cho, 2012 [33] | 39,332 | 52.0 | 51.2 | 2000–2008 | USA | Registry (OPTN/UNOS) | Recipient and donor age, gender, race, CAD, CVD, DM, PVD, pulmonary, malignancy, CMV, DGF, rejection treatment | 8 |

| Croke, 2010 [27] | 12,662 | NR | NR | 1985–2007 | Australia/ New Zealand | Registry (ANZDATA) | Donor and recipient variables,transplant year,type of initial CNI | 8 |

| Connolly, 1996 [31] | 516 | NR | 67.4 | 1989–1993 | UK | Single-center | Recipient and donor age and gender, donor type, DGF, CIT, PRA, ARE, warm ischemia time, | 8 |

| Asderakis, 2001 [29] | 788 | 42.1 | 67.8 | 1990–1995 | UK | Single-center | Recipient and donor gender, donor age, DGF, CIT, ARE, immunosuppression | 8 |

| Opelz, 2007 [35] | 135,970 | NR | 61.6 | 1985–2004 | Germany | Registry (CTS) | Recipient and donor age, gender, and race, PRA, CIT, transplant year, time on dialysis, original disease, previous transplant, pre-transplant dialysis, recipient geographical origin, immunosuppression | 8 |

| Amatya, 2010 [36] | 229 | 40.5 | 59.4 | 1997–2007 | USA | Single-center | Recipient age, gender, and race, BMI, PRA, previous transplant, CIT, WIT | 8 |

| Zukowski, 2014 [40] | 232 | 37.7 | 63.8 | 1997–1998 | Poland | Multi-center | Univariate | 6 |

| Fellstrom, 2005 [41] | 2102 | 51 | 65.2 | 1996–1997 | Europe | Multi-center | Univariate | 6 |

| Summers 2010 [37] | 9134 | 47 | 61.4 | 2000–2007 | UK | Registry (UK transpalnt registry) | Recipient age, donor age, CIT | 6 |

| Van 1996 [39] | 1289 | 32.8 | 60.9 | 1966–1994 | Netherlands | Single-center | Recipient and donor age and gender, type of immnnosuppression, presensitisation, DM, and living or post-mortem donor | 8 |

| Lynch 2013 [38] | 31,534 | N/A | N/A | 2000–2010 | USA | Registry (SRTR) | Not reported | 8 |

ANZDATA Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, AR acute rejection, ARE acute rejection episode, ATG antithymocyte globulin, BMI body mass index, CAD coronary artery disease, CIT cold ischemic time, CMV cytomegalovirus, CNI calcineurin inhibitor, Cr creatinine, CTS Collaborative Transplant Study, CVD cardiovascular disease, DGF delayed graft function, DM diabetes mellitus, GFR glomerular filtration rate, HBV hepatitis B virus, HCV hepatitis C virus, NR not reported, OPTN the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, PRA panel reactive antibodies, pre-TX pre-transplant, PVD peripheral vascular disease, SBP systolic blood pressure, SRTR Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipient, UNOS United Network for Organ Sharing, USRDS United States Renal Data System, WIT warm ischemic time

Primary outcomes

HLA per mismatch and overall graft failure

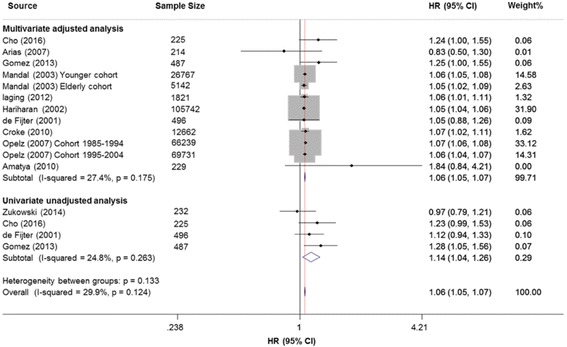

Eleven studies (289,987 adult recipients) reported data on HLA mismatching and overall graft failure. The pooled analysis revealed that each incremental increase of HLA-mismatches was significant associated with a higher risk of overall graft failure, both in univariable-unadjusted summary estimates (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.04–1.26; P = 0.008; Fig. 2) and multivariable-adjusted summary estimates (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 1.05–1.07; P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The heterogeneity was low (I2 = 24.8 and 27.4%, respectively). Detailed predefined subgroup analyses were listed in Table 2. The effect estimates did not changed significantly after stratification for sample size (≥10,000 vs < 10,000), data source (multi-centered vs single-centered), donor source (cadaveric vs living and cadaveric), geographic locations (European, North America, Asia and Oceania) and year period (prior to 1995 vs not prior to 1995). In sensitivity analysis, the summary estimates were not modified after excluding one study at a time. Subsequent univariate meta-regression indicated that these factors did not significantly change the overall effect (Additional file 5: Fig. S1). Publication bias was not significant (Additional file 6: Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of the association between HLA per mismatch and overall graft failure, using both of univariable-unadjusted and multivariable-adjusted effect estimates

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses of overall graft failure associated with HLA per mismatch and HLA-DR mismatches

| HLA per mismatch | HLA-DR mismatches | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | No. of recipients (cohorts) | HR (95% CI) | I 2 | P a | No. of recipients (cohorts) | HR (95% CI) | I 2 | P a |

| Sample size | 0.835 | 0.011 | ||||||

| ≥10,000 | 281,141 (5) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | 49.1 | 145,351 (2) | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | 0 | ||

| < 10,000 | 8614 (7) | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 17.3 | 4652 (5) | 1.27 (1.12–1.43) | 48.4 | ||

| Nature of data | 0.133 | 0.076 | ||||||

| Univariable-unadjusted | 1440 (4) | 1.14 (1.04–1.26) | 24.8 | 2598 (2) | 1.39 (1.05–1.83) | 70.0 | ||

| Multivariable-adjusted | 286,755 (12) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | 27.4 | 150,003 (7) | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | 58.3 | ||

| Data source | 0.683 | 0.011 | ||||||

| Registry/Multi-center | 286,283 (6) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | 38.9 | 145,351 (2) | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | 0 | ||

| Single-center | 3472 (6) | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 26.6 | 4652 (5) | 1.27 (1.12–1.43) | 48.4 | ||

| Donor source | 0.027 | 0.616 | ||||||

| Cadaveric | 138,516 (5) | 1.07 (1.06–1.07) | 0.00 | 41,284 (5) | 1.08 (1.04–1.11) | 66.4 | ||

| Living and Cadaveric | 151,239 (7) | 1.05 (1.05–1.06) | 16.4 | 108,719 (2) | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) | 55.4 | ||

| Geographical locations | 0.053 | 0.033 | ||||||

| Europe | 138,988 (6) | 1.07 (1.06–1.08) | 0.00 | 1952 (4) | 1.32 (1.09–1.60) | 59.7 | ||

| North America | 137,880 (4) | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | 2.1 | 145,351 (2) | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | 0 | ||

| Asia | 225 (1) | 1.24 (1.00–1.55) | – | 2700 (1) | 1.23 (1.05–1.45) | – | ||

| Oceania | 12,662 (1) | 1.07 (1.03–1.12) | – | 0 | – | – | ||

| Year period | 0.175 | 0.026 | ||||||

| Prior to 1995 | 103,915 (6) | 1.06 (1.05–1.07) | 0.00 | 148,051 (3) | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) | 26.8 | ||

| Not prior to 1995 | 185,626(5) | 1.06 (1.05–1.08) | 60.1 | 4054 (4) | 1.36 (0.98–1.88) | 59.7 | ||

| NR | 214 (1) | 0.83 (0.51–1.34) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

The effect estimates were stratified for sample size (≥10,000 vs < 10,000), data source (multi-centered vs single-centered), donor source (cadaveric vs living and cadaveric), geographic locations (European, North America, Asia and Oceania) and year period (prior to 1995 vs not prior to 1995)

aP value for heterogeneity

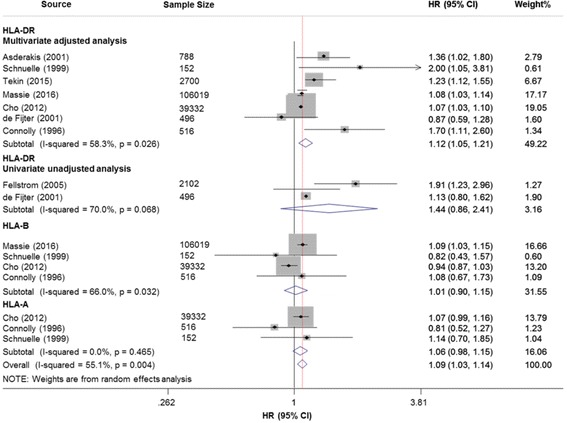

HLA-DR mismatches and overall graft failure

Eight studies with 152,105 adult recipients were analyzed to investigate the association between HLA-DR mismatching and overall graft failure. The pooled results revealed an unadjusted HR of 1.44 (95% CI: 0.86–2.41; P = 0.160) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 70.0%). After adjustment, each incremental increase of HLA-DR mismatches was significant associated with 12% higher risk of overall graft failure (HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 1.05–1.21; P = 0.002; Fig. 3), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 58.3%). Sensitivity analysis with a fixed-effects model obtained similar results (HR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.05–1.11; P < 0.001). Subsequent subgroup analysis demonstrated that the effect was not modified after stratification for sample size, data source, donor source and geographical locations (Table 2). The effect estimates remained stable after excluding one study at a time. Considering only 8 studies included in meta-analysis, we did not perform a meta-regression.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of the association between HLA-A, -B, -DR mismatches and overall graft failure

In addition, three studies with 41,957 recipients evaluated 1 or 2 DR-mismatches versus 0 DR-mismatches. Compared with 0 mismatches in HLA-DR antigen, 1 mismatches and 2 mismatches were all associated with higher risk of overall graft failure, with pooled HRs of 1.12 (95% CI: 1.04–1.21; P = 0.002) and 1.15 (95% CI: 1.05–1.25; P = 0.002), respectively (Additional file 7: Fig. S3). In both pooled analysis, there was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

HLA-B mismatches and overall graft failure

Associations of HLA-B epitope and overall graft failure were reported in 4 studies with 146,019 recipients. The pooled analysis demonstrated that each incremental increase of HLA-B mismatches was not associated with higher risk of overall graft failure (HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.90–1.15; P = 0.834; Fig. 3), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 66.0%). Sensitivity analysis with a fixed-effects model obtained similar effect estimates (HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.89–1.14; P = 0.079). In addition, the effect estimates did not changed significantly after stratification for sample size (≥10,000 vs < 10,000) of cohorts.

HLA-A mismatches and overall graft failure

Only 3 studies (40,000 recipients) reported data on the association of HLA-A epitope and overall graft failure. The results revealed an insignificant association (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.98–1.14; P = 0.121; Fig. 3), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Sensitivity analysis with a random-effects model showed similar results (HR: 1.06; 95% CI: 0.98–1.15; P = 0.121). The results should be cautiously interpreted because of only three studies included.

Secondary outcomes

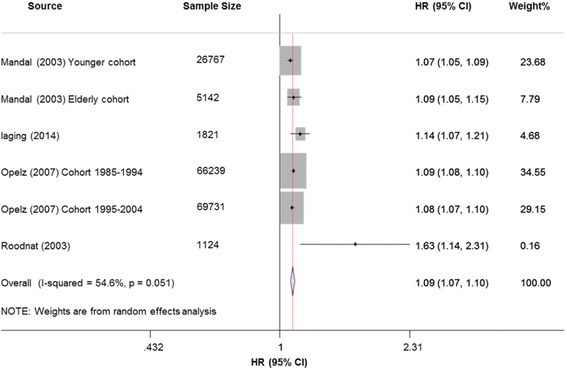

Death-censored graft failure

We included 101,093 recipients from 4 cohorts. Each incremental increase of HLA mismatches was associated with a higher risk of death-censored graft failure, with summary HR of 1.09 (95% CI: 1.06–1.12; P < 0.001; Fig. 4), and moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 70.9%). Sensitivity analysis with a fixed-effects model showed similar results (HR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.08–1.10; P < 0.001). The summary estimates were not modified after including only large sample size of cohorts (> 10,000 recipients) (Additional file 8: Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of the association between HLA per mismatch and death-censored graft failure

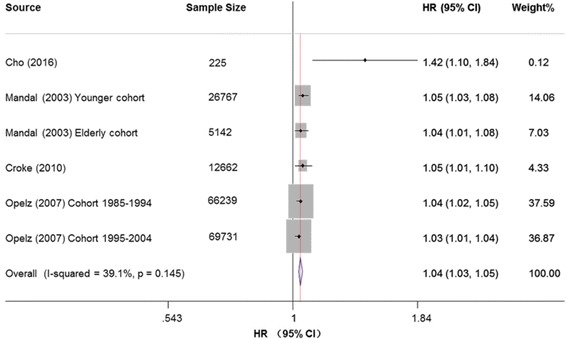

All-cause mortality

We included 180,766 recipients from 4 cohorts. Each incremental increase of HLA mismatches was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality rates (HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07; P = 0.001; Fig. 5). The heterogeneity was moderate (I2 = 65.3%). Summary estimates did not changed significantly after analyzing with a fixed-effects model (HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02–1.07; P = 0.001). After stratification for sample size of cohorts (≥10,000 vs < 10,000), the effect estimates were not modified (HR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.02–1.05; P < 0.001; I2 = 27.8%, Additional file 8: Fig. S4). However, the results should be cautiously interpreted due to small number of included studies (n = 4).

Fig. 5.

Forest plots of the association between HLA per mismatch and all-cause mortality

Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the magnitude effect of HLA mismatching on post-transplant survival outcomes of adult kidney transplantation. The analysis included 23 studies with a large sample of subjects (totally 486,608 recipients). The results indicated that each incremental increase of HLA mismatches was significantly associated with higher risks of overall graft failure, death-censored graft failure and all-cause mortality. The pooled results also indicated that HLA-DR mismatches were significantly associated with a 12% higher risk of overall graft failure. We also observed that HLA-A per mismatch was associated with a 6% higher risk of overall graft failure, but the association was insignificant. There was no significant association between HLA-B mismatching and graft survival. All included studies were in high methodological quality and the heterogeneity between studies was acceptable in each pooling analysis. In addition, we found that sample size or recipient ethnicity may be potential sources of heterogeneity.

Human HLA genes are located on chromosome 6 and code for 3 major class I alleles (HLA-A, -B, -C) and 3 major class II alleles (HLA-DR, -DQ, -DP). Polymorphisms in HLA, especially HLA-A, -B, and -DR loci, are important biological barriers to a successful transplantation [42, 43]. As closely HLA-matched graft is less likely to be recognized and rejected, HLA mismatching has a substantial impact on prolongation of graft survival. With the emergence of potent immunosuppressive agents that steadily improved the graft survival rates, the impact of HLA compatibility seems to be minimized [42, 44]. But the recent Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDTR) survey with 12,662 recipients still demonstrated that each incremental increase of HLA mismatches was significantly associated with higher risk of graft failure and rejection [27]. Another recent survey from Massie et al. [19] with 106,019 recipients from the Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients (SRTR) database revealed that HLA-B and -DR mismatches were all significant associated with worse graft survival outcomes. Using multivariable-adjusted data (adjusting for other determinant confounders such as donor and recipient age, gender, combined disease, serum creatinine levels, ischemic times, etc.), the present analysis indicated that HLA per mismatch was associated with an increased risk of overall graft failure (9%), death-censored graft failure (6%) and all-cause mortality (4%). The pooled results were in favor of recommendations of the latest European Renal Best Practice Transplantation Guidelines, which recommended that matching of HLA-A, -B, and -DR whenever possible [8].

The meta-analysis suggested that HLA-DR per mismatch was significant associated with a 12% higher risk of overall graft failure. Besides, a subsequent analysis suggested that compared with 0 DR-mismatches, 1 and 2 mismatches were significant associated with 12 and 15% higher risk of overall graft failure, respectively. The pooled results were in favor of the kidney allocation guideline recommendations in almost all countries, such as the current US kidney allocation system, the revised United Kingdom kidney allocation scheme, and the latest European Renal Best Practice Transplantation Guidelines, which all highlighted the importance of HLA-DR testing [5–8].

Notably, the present analysis revealed a tendency that HLA-A mismatching had an impact on overall graft survival as there were only 3 studies included with a pooled HR of 1.06 (95% CI: 0.98–1.14). However, we did not observe a significant association between HLA-B mismatching and overall graft survival (HR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.90–1.15). Our pooled results were inconsistent with the recommendations of the revised United Kingdom kidney allocation scheme, which eliminated the impact of HLA-A similarity instead of HLA-B similarity [7]. Moreover, miscellaneous factors can result in inferior outcomes [45]. For instance, inferior graft outcomes could be related to high risk for rejection particularly antibody-mediated rejection [45–47]. Inferior patient survival could partly be associated with consequences of enhanced immunosuppression [45]. Consequently, the pooled results should be cautiously interpreted and further studies should be conducted to investigate the impact of HLA-A mismatching on graft and recipient survival outcomes.

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression was conducted to explore heterogeneity between studies. In subgroup analysis of the association between HLA per mismatch and overall graft failure, we found that after stratification for donor source (cadaveric vs living and cadaveric), the heterogeneity decreased to insignificant (I 2 = 0 and 16.4, respectively). But subsequent meta-regression analysis revealed that donor source did not change the overall effect significantly. In subgroup analysis of the association between HLA-DR mismatching and overall graft failure, we found that ethnicity and recipient sample size were potential source of heterogeneity. Large sample size of cohorts usually demonstrated more stable results. Besides, ethnic diversity was a potential source of heterogeneity probably because of varying HLA polymorphisms in the genetic makeup of the geographically distinct cohorts.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of our meta-analysis are large sample of subjects (totally 486,608 recipients) and strict study design. Besides, we used multivariable-adjusted data for pooling analysis, which adjusted for some primary determinant confounders. However, the present meta-analysis had some limitations. Firstly, the absence of randomized controlled trials was the biggest limitation of this meta-analysis. Secondly, several studies have suggested that other HLA loci, such as HLA-C and -DQ locus, may contribute to poorer graft outcomes [48–50], but this meta-analysis only included the HLA-A, -B and -DR loci. Thirdly, heterogeneity is inevitable in some outcomes. We conducted several subgroup and meta-regression analyses to explore the potential source of heterogeneity, and used random-effects models to incorporate heterogeneity between studies. Fourthly, few studies included could provide data about induction agent, maintenance agent or PRA, so that it cannot be achieved to do the stratified analysis.

Conclusions

HLA mismatching was still a critical prognostic factor that affects graft and recipient survival. HLA-DR mismatching has a substantial impact on recipient’s graft survival. HLA-A mismatching has minor but not significant impact on graft survival outcomes. Further studies should be conducted to confirm the impact of HLA-A similarity.

Additional files

Supplemental Methods. (DOCX 45 kb)

Table S1. The MOOSE checklist. (DOCX 103 kb)

Table S2. The PRISMA checklist. (DOCX 90 kb)

Table S3. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) score for evaluation of study quality. (DOCX 73 kb)

Figure S1. Meta-regression of HLA mismatches on graft failure for primary determinant confounders (A: Sample size; B: Data source; C: Donor source; D: Geographical locations). (DOCX 608 kb)

Figure S2. Funnel plot and Egger test for publication bias among studies that evaluated association HLA per mismatch and overall graft failure. (A: Funnel plot; B: Egger test). (DOCX 81 kb)

Figure S3. Forest plot that evaluated the impact of 1 or 2 HLA-DR mismatches versus 0 mismatches on overall graft failure. (DOCX 587 kb)

Figure S4. Forest plot after stratification for sample size (≥10,000 vs < 10,000) of cohorts, to evaluate association between (A) HLA per mismatch and death-censored graft failure; (B) HLA per mismatch and all-cause mortality. (DOCX 1230 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

The design of the study was supported by Beijing key laboratory of molecular diagnosis and study on pediatric genetic diseases (No. BZ0317). The collection, analysis, and interpretation of data were supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, the registry of rare diseases in children (No. 2016YFC0901505).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its additional files.

Authors’contributions

All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis. Study concept and design: JD. Extraction, analysis and interpretation of data: XS and XZ. Drafting of the manuscript: XS. Critical revision of the manuscript: JD, JL, XZ and WH. Statistical analysis: XS, JL, XX and BS. Technical support: JL and WH. All authors have read and agreed to the submission to this journal of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANZDATA

Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry

- AR

Acute rejection

- ARE

Acute rejection episode

- ATG

Antithymocyte globulin

- BMI

Body mass index

- CAD

Coronary artery disease

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIT

Cold ischemic time

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- CNI

Calcineurin inhibitor

- Cr

Creatinine

- CTS

Collaborative Transplant Study

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DGF

Delayed graft function

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HLA

Human leukocyte antigen

- HR

Hazard ratio

- NR

Not reported

- OPTN

The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- PRA

Panel reactive antibodies

- pre-TX

Pre-transplant

- PVD

Peripheral vascular disease

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SRTR

The Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipient

- UNOS

The United Network for Organ Sharing

- USRDS

The United States Renal Data System

- WIT

Warm ischemic time

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12882-018-0908-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Xinmiao Shi, Email: shixinmiaozhenhao@163.com.

Jicheng Lv, Email: jichenglv75@gmail.com.

Wenke Han, Email: hanwenke@medmail.com.cn.

Xuhui Zhong, Email: xuhui7876@126.com.

Xinfang Xie, Email: 15652931826@126.com.

Baige Su, Email: subaige520@163.com.

Jie Ding, Email: djnc_5855@126.com.

References

- 1.Ferrari P, Weimar W, Johnson RJ, Lim WH, Tinckam KJ. Kidney paired donation: principles, protocols and programs. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(8):1276–1285. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, World Health Organization. Organ Donation and Transplantation Activities 2014. http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-reports-2014/ Assessed Apr 2016.

- 3.Ai Dhaybi O, Bakris GL. Renal targeted therapies of antihypertensive and cardiovascular drugs for patients with stages 3 through 5d kidney disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(3):450–8. doi: 10.1002/cpt.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Otaibi T, Gheith O, Mosaad A, Nampoory MR, Halim M, Said T, et al. Human leukocyte antigen-DR mismatched pediatric renal transplant: patient and graft outcome with different kidney donor sources. Exp Clin Transplant. 2015;13(Suppl 1):117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Wynn JJ, Williams WW, Roberts JP. Transplanting kidneys without points for HLA-B matching: consequences of the policy change. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(8):1712–1718. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leffell MS, Zachary AA. The national impact of the 1995 changes to the UNOS renal allocation system. United network for organ sharing. Clin Transpl. 1999;13(4):287–295. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.130402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson RJ, Fuggle SV, O'Neill J, Start S, Bradley JA, Forsythe JL, et al. Factors influencing outcome after deceased heart beating donor kidney transplantation in the United Kingdom: an evidence base for a new national kidney allocation policy. Transplantation. 2010;89(4):379–386. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181c90287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramowicz D, Cochat P, Claas FH, Heemann U, Pascual J, Dudley C, et al. European renal best practice guideline on kidney donor and recipient evaluation and perioperative care. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(11):1790–1797. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Altman DG. PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Renal Best Practice Transplantation Guideline Development Group ERBP guideline on the management and evaluation of the kidney donor and recipient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(Suppl 2):i1–i71. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(Suppl 3):s1–s155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson G, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa, Ontario: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2013. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Assessed 15 Dec 2015.

- 14.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cohrane handbook for sustematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0, The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. http://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed Mar 2011.

- 15.Cheng YJ, Nie XY, Chen XM, Lin XX, Tang K, Zeng WT, et al. The role of macrolide antibiotics in increasing cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(20):2173–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massie AB, Leanza J, Fahmy LM, Chow EK, Desai NM, Luo X, et al. A risk index for living donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(7):2077–2084. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Fijter JW, Mallat MJ, Doxiadis II, Ringers J, Rosendaal FR, Claas FH, et al. Increased immunogenicity and cause of graft loss of old donor kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(7):1538–46. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1271538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roodnat JI, van Riemsdijk IC, Mulder PG, Doxiadis I, Claas FH, IJzermans JN, et al. The superior results of living-donor renal transplantation are not completely caused by selection or short cold ischemia time: a single-center, multivariate analysis. Transplantation. 2003;75(12):2014–2018. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000065176.06275.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tekin S, Yavuz HA, Yuksel Y, Yucetin L, Ateş I, Tuncer M, et al. Et al. kidney transplantation from elderly donor. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(5):1309–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandal AK, Snyder JJ, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ, Silkensen JR. Does cadaveric donor renal transplantation ever provide better outcomes than live-donor renal transplantation? Transplantation. 2003;75(4):494–500. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000048381.48473.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arias LF, Blanco J, Sanchez-Fructuoso A, Prats D, Duque E, Sáiz-Pardo M, et al. Histologic assessment of donor kidneys and graft outcome: multivariate analyses. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(5):1368–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.01.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho H, Yu H, Shin E, Kim YH, Park SK, Jo MW. Risk factors for graft failure and death following geriatric renal transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gómez EG, Hernández JP, López FJ, Garcia JR, Montemayor VG, Curado FA, et al. Long-term allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(10):3599–3602. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croke R, Lim W, Chang S, Campbell S, Chadban S, Russ G, et al. HLA-mismatches increase risk of graft failure in renal transplant recipients initiated on cyclosporine but not tacrolimus. Nephrology. 2010;15:38. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laging M, Kal-van Gestel JA, van de Wetering J, Ijzermans JN, Weimar W, Roodnat JI. The relative importance of donor age in deceased and living donor kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2012;25(11):1150–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2012.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asderakis A, Dyer P, Augustine T, Worthington J, Campbell B, Johnson RW. Effect of cold ischemic time and HLA matching in kidneys coming from "young" and "old" donors: do not leave for tomorrow what you can do tonight. Transplantation. 2001;72(4):674–678. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108270-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnuelle P, Lorenz D, Mueller A, Trede M, Van Der Woude FJ. Donor catecholamine use reduces acute allograft rejection and improves graft survival after cadaveric renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 1999;56(2):738–746. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connolly JK, Dyer PA, Martin S, Parrott NR, Pearson RC, Johnson RW. Importance of minimizing HLA-DR mismatch and cold preservation time in cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61(5):709–714. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199603150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hariharan S, McBride MA, Cherikh WS, Tolleris CB, Bresnahan BA, Johnson CP. Post-transplant renal function in the first year predicts long-term kidney transplant survival. Kidney Int. 2002;62(1):311–318. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho YW, Lemp N, Shah T, Sampaio MS, Hutchinson IV, Kasahara A, et al. Long-term risk factors of kidney graft survival in the modern immunosuppression era. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:490. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laging M, Kal-van Gestel JA, Haasnoot GW, Claas FH, van de Wetering J, Ijzermans JN, et al. Transplantation results of completely HLA-mismatched living and completely HLA-matched deceased-donor kidneys are comparable. Transplantation. 2014;97(3):330–336. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000435703.61642.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opelz G, Döhler B. Effect of human leukocyte antigen compatibility on kidney graft survival: comparative analysis of two decades. Transplantation. 2007;84(2):137–143. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000269725.74189.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amatya A, Florman S, Paramesh A, Amatya A, Mcgee J, Killackey M, et al. HLA-matched kidney transplantation in the era of modern immunosuppressive therapy. Dial Transplant. 2010;39(5):193–198. doi: 10.1002/dat.20439. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Summers DM, Johnson RJ, Allen J, Fuggle SV, Collett D, Watson CJ, et al. Analysis of factors that affect outcome after transplantation of kidneys donated after cardiac death in the UK: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9749):1303–1311. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60827-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lynch S, Tinckam K, Kim J. Increasing HLA DR mismatches is associated with inferior kidney allograft outcome in low immune risk living donor kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:420. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Saase JL, Mallat MJ, van der Woude FJ, van Bockel JH, van Es LA. Results of renal transplantation in Leiden, 1966-1994, and prognostic factors. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1996;140(15):827–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zukowski M, Kotfis K, Kaczmarczyk M, Biernawska J, Szydłowski L, Zukowska A, et al. Influence of selected factors on long-term kidney graft survival-a multivariable analysis. Transplant Proc. 2014;46(8):2696–2698. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fellström B, Holdaas H, Jardine AG, Nyberg G, Grönhagen-Riska C, Madsen S, et al. Risk factors for reaching renal endpoints in the assessment of Lescol in renal transplantation (ALERT) trial. Transplantation. 2005;79(2):205–212. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000147338.34323.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Broeders N, Racapé J, Hamade A, Massart A, Hoang AD, Mikhalski D, et al. A new HLA allocation procedure of kidneys from deceased donors in the current era of immunosuppression. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(2):267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laperrousaz S, Tiercy S, Villard J, Ferrari-Lacraz S. HLA and non-HLA polymorphisms in renal transplantation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13668. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Süsal C, Opelz G. Current role of human leukocyte antigen matching in kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2013;18(4):438–444. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283636ddf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Legendre C, Canaud G, Martinez F. Factors influencing long-term outcome after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2014;27(1):19–27. doi: 10.1111/tri.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu K, Budde K, Schmidt D, Neumayer HH, Lehner L, Bamoulid J, et al. The inferior impact of antibody-mediated rejection on the clinical outcome of kidney allografts that develop de novo thrombotic microangiopathy. Clin Transpl. 2016;30(2):105–117. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nin M, Coitiño R, Kurdian M, Orihuela L, Astesiano R, Garau M, et al. Acute antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplant based on the 2013 Banff criteria: single-center experience in Uruguay. Transplant Proc. 2016;48(2):612–615. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiebe C, Pochinco D, Blydt-Hansen TD, Ho J, Birk PE, Karpinski M, et al. Class II HLA epitope matching-a strategy to minimize de novo donor-specific antibody development and improve outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(12):3114–3122. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kosmoliaptsis V, Gjorgjimajkoska O, Sharples LD, Chaudhry AN, Chatzizacharias N, Peacock S, et al. Impact of donor mismatches at individual HLA-A, -B, -C, -DR, and -DQ loci on the development of HLA-specific antibodies in patients listed for repeat renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2014;86(5):1039–48. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeVos JM, Gaber AO, Knight RJ, Land GA, Suki WN, Gaber LW, et al. Donor-specific HLA-DQ antibodies may contribute to poor graft outcome after renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2012;82(5):598–604. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Methods. (DOCX 45 kb)

Table S1. The MOOSE checklist. (DOCX 103 kb)

Table S2. The PRISMA checklist. (DOCX 90 kb)

Table S3. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) score for evaluation of study quality. (DOCX 73 kb)

Figure S1. Meta-regression of HLA mismatches on graft failure for primary determinant confounders (A: Sample size; B: Data source; C: Donor source; D: Geographical locations). (DOCX 608 kb)

Figure S2. Funnel plot and Egger test for publication bias among studies that evaluated association HLA per mismatch and overall graft failure. (A: Funnel plot; B: Egger test). (DOCX 81 kb)

Figure S3. Forest plot that evaluated the impact of 1 or 2 HLA-DR mismatches versus 0 mismatches on overall graft failure. (DOCX 587 kb)

Figure S4. Forest plot after stratification for sample size (≥10,000 vs < 10,000) of cohorts, to evaluate association between (A) HLA per mismatch and death-censored graft failure; (B) HLA per mismatch and all-cause mortality. (DOCX 1230 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its additional files.