Abstract

Background

Physical inactivity is associated with excess weight and adverse health outcomes. We synthesize the evidence on physical inactivity and its social determinants in Arab countries, with special attention to gender and cultural context.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Popline, and SSCI for articles published between 2000 and 2016, assessing the prevalence of physical inactivity and its social determinants. We also included national survey reports on physical activity, and searched for analyses of the social context of physical activity.

Results

We found 172 articles meeting inclusion criteria. Standardized data are available from surveys by the World Health Organization for almost all countries, but journal articles show great variability in definitions, measurements and methodology. Prevalence of inactivity among adults and children/adolescents is high across countries, and is higher among women. Some determinants of physical inactivity in the region (age, gender, low education) are shared with other regions, but specific aspects of the cultural context of the region seem particularly discouraging of physical activity. We draw on social science studies to gain insights into why this is so.

Conclusions

Physical inactivity among Arab adults and children/adolescents is high. Studies using harmonized approaches, rigorous analytic techniques and a deeper examination of context are needed to design appropriate interventions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-018-5472-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Physical activity, Social determinants, Gender, Culture, Arab countries

Background

Global increases in body mass index, raised blood pressure and cardiovascular disease have been attributed in part to the reduction in physical activity resulting from changes in the organization of labor and transportation, and to increases in sedentary behavior. The evidence on the magnitude of these changes and their consequences for health is well recognized. The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks physical inactivity as the fourth leading cause of global mortality, estimating that it results in 3.2 million deaths globally, mainly due to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and some cancers [1–6]. Analyses of the Global Burden of Disease estimate that insufficient physical activity accounts for an estimated 13.4 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) related to ischemic heart disease, diabetes and stroke [7].

There are major variations in the prevalence of physical inactivity across regions and among countries. In the Arab region, alarming predictions have been made in light of very unfavorable combinations of risk factors related to body mass index, its determinants including physical activity, and its health consequences [8–10]. Some studies have compared indicators across countries [11–15], but there have not been comprehensive assessments of the prevalence and determinants of physical inactivity across the Arab region. Yet, such regionally specific assessments are key to identify patterns and formulate interventions, and would be especially timely, given mounting evidence on the health effects of sedentary behaviour and physical inactivity, the growing awareness of the need for population interventions, and the urgency of scaling up policies and programs to increase physical activity in low and middle income countries [16]. In addition, there is a need to go beyond simplistic explanations of observed patterns in terms of religion or education.

Hence, this study was designed to review research on the subject, assess levels and variability in physical inactivity across countries and social groups, and gain insights into the extent to which social determinants, in particular those related to gender, could explain such unfavorable indicators. The diversity of indicators and measures in the region, and the difficulty of obtaining original survey data precluded the possibility of conducting a systematic review or meta-analysis. But we thought it was important to take stock of what was known about physical inactivity in the region and to review the explanations that are offered for observed levels, in order to identify patterns and to inform policies designed to increase physical activity.

The review proceeds as follows. We first present a summary of the evidence from studies published in peer-reviewed journals, including the availability and comparability of studies and the instruments used. Secondly, we provide a synthesis of prevalence levels based on the reports of surveys that have used standardized definitions and measurements. We then bring together the results of studies that examined the social determinants of physical activity, with special attention to those related to gender and cultural factors. Lastly we draw the implications of these results for research and policies.

Methods

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We sought to retrieve research published in refereed journals and reports of surveys, and our approach was three-pronged. First, we searched for articles in refereed journals investigating physical inactivity in countries of the Arab region, published between January 2000 and January 2016, in MEDLINE, Popline and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) databases. Various combinations of MeSH terms and key words were used, related to physical activity/ inactivity, sedentary lifestyle, exercise, sports, its prevalence, incidence, epidemiology, the burden it represents, and social or cultural factors. Details are shown in Additional file 1. Studies published in any language were retrieved. Two researchers conducted title and abstract screening, followed by full-text screening, checking to harmonize results regarding inclusion or exclusion; disagreements were discussed by the team as a whole and resolved. This was done according to the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) appraisal tool for systematic reviews [17]. In addition to the electronic search, we searched reference lists of the articles identified.

Sources were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: assessed physical activity or inactivity as an outcome or a determinant; were conducted among residents of Arab countries (the 22 countries of the Arab League: Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Yemen); described the design and methods; reported on sample size; described how physical activity/inactivity was measured; reported on the prevalence of physical activity/inactivity. Multi-country studies were included if they presented data on at least one Arab country. Studies conducted exclusively on patients with a particular disease diagnosis, and studies conducted on Arabs residing outside the Arab region were excluded. To be included, articles needed to fulfill quality criteria informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [18], including clear eligibility criteria for study selection, description of information sources, data and variables; we excluded studies that did not report on sample size, age range of study population, and those that presented unclear or inconsistent numbers.

Secondly, we retrieved the reports of surveys on physical activity conducted by international organizations in collaboration with country partners; these surveys generally use standardized instruments and the two main sources are the World Health Organization (WHO) surveys on non-communicable disease risk factors (STEPS) which include modules on physical activity among adults; and the Global School-based Student Health Surveys (GSHS) which measure activity among adolescents. We present results separately for studies based on national surveys using standardized definitions and measures, and whose results represent comparable and higher-quality estimates.

A third part of the review was to retrieve data from sources that considered physical inactivity in relation to social factors such as age, marriage, education, employment, residence, and those that examined cultural and social barriers to physical activity. We sought to gain insights into the socio-cultural context of physical activity, and to explain the patterns that emerged from the analysis of the quantifiable data. We extracted notes and themes from those sources that included qualitative information, and provide a critical synthesis of main findings. Thus, this review draws both on rigorous quantitative analyses and a narrative synthesis of qualitative studies.

Data extraction and analysis

Citations from search results of databases were imported into the reference manager EndNote and duplicates removed. We used the open-source Open Data Kit (ODK) (https://ona.io/) to create the data entry protocol. The data extracted for each study included: (1) article identification (title, author/s, publication year, journal, country/ies of study); (2) research design, setting, sample size, study population, gender, and age; (3) definition of physical activity/inactivity, instrument used, reported prevalence; and, (4) demographic, economic, lifestyle and social correlates of physical inactivity. In addition, we retrieved themes from those studies that examined the social context of physical activity and provided information about gender and cultural differences.

We retrieved the most recent data from STEPS and GSHS surveys. For countries where no published reports were available, we retrieved any data available from the WHO website.

Regarding the outcome variable, because of the diversity of definitions and measures of physical activity, we found that the most consistent way to report the results was to use physical inactivity, which refers to not engaging in any physical activity and/or being in the lowest category of physical activity, however physical activity was defined in the study. This is consistent with other studies that have reviewed physical activity across the world [13].

We present results separately for adults and for children/adolescents. We defined as adults those respondents aged 18 or older, or those who were categorized as adults in the articles; younger respondents were categorized as children/adolescents. In the discussion, we build on the narrative synthesis of qualitative studies.

Results

The evidence on physical inactivity

Sources and quality of data

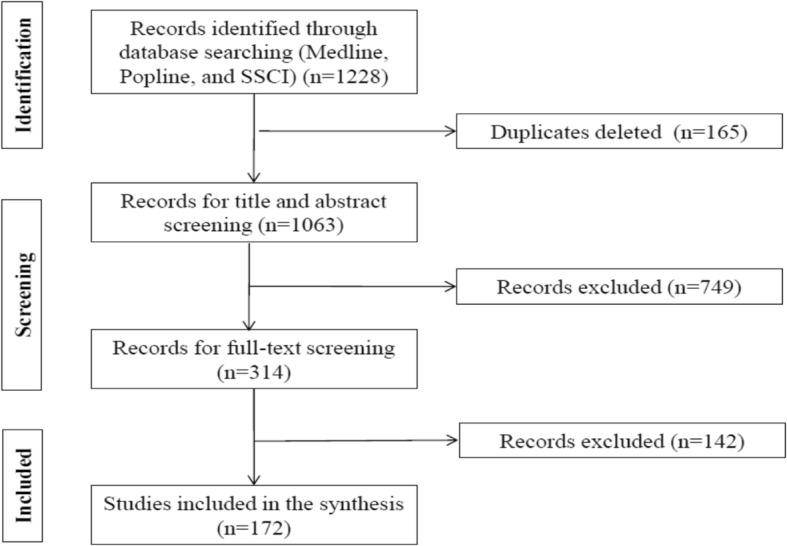

Our search retrieved 1,228 articles, of which 172 met the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 provides a flow chart of the review’s inclusion and exclusion process. The included articles referred to a total of 157 datasets: 149 from studies conducted in a single country and 8 conducted as part of multi-country studies; the results of multi-country studies are counted once for each individual country. Some articles were based on the same datasets, including six articles based on STEPS and GSHS surveys. Only 16/143 journal articles reported on surveys using nationally representative samples; qualitative data were retrieved from five qualitative studies and from four mixed methods studies.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the review’s inclusion and exclusion process

All STEPS and GSHS, and 125/157 journal articles include both men/boys and women/girls. GSHS surveys (usually on adolescents 13-15) have been conducted in all but four countries of the region (Bahrain, Comoros, KSA, and Somalia). STEPS surveys usually include adults aged 25-64. Age categories in journal articles are more diverse. 12 countries had both STEPS and GSHS surveys. Unlike GSHS, not all STEPS were based on nationally representative samples (exceptions were Algeria, Mauritania, Oman and Sudan). Additional results about the prevalence of physical inactivity and its determinants are available from journal articles that used the World Health Surveys (WHS) as data sources. STEPS are based on household surveys and GSHS on school populations, while the settings in journal articles included schools (28%), health facilities (27%), households (16%), and universities (15%).

Table 1 shows disparities in the available evidence: for some countries there are very few studies (Algeria, Comoros, Djibouti, Iraq, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen), while for others many more sources are available (for example 40 for Saudi Arabia). There is also a variability in sample size, with most studies in the range of 200-2000 and a few large studies including several thousand respondents.

Table 1.

The evidence on physical activity in Arab Countries: studies, sample sizes and instruments

| Country | Total number of studies | Data from Reports/Factsheetsa | Data from Journal Articles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (#) | Sample size/range | Single country studies (#) | Multi-country studies (#) | Sample size/range | Nationally representative studies (#) | Instruments usedb,c | ||

| Algeria | 4 | 2 [116, 117] | 4102 – 4532 | 1 [118] | 1 [15] | 293 – 4698d | - | Locally Validated Questionnaire [15] |

| Bahrain | 4 | 1 [119] | 1769 | 4 [82, 120–122] | 0 | 142 – 2013 | 1 [122] | WHO Heart and Health Questionnaire [120] |

| Comoros | 3 | 1 [123] | 5556 | 0 | 2 [12, 13] | 1492 – 212021d | - | IPAQ [12, 13] |

| Djibouti | 1e | 1 [124] | 1777 | 0 | 1 [11, 58] | 829 – 882 | 1 [58] | PACE+ [11, 58] |

| Egypt | 12e | 2 [125, 126] | 2568 – 5300 | 7 [34, 46, 74, 127–130] | 4 [11, 21, 58, 131, 132] | 188 – 3271 | 1 [58] | IPAQ [131] PACE+ [11, 58] |

| Iraq | 3 | 2 [133, 134] | 2038 – 4120 | 1 [135] | 0 | 200 | - | - |

| Jordan | 15e | 2 [136, 137] | 2197 – 3654 | 12 [61, 64, 70, 72, 80, 81, 138–143] | 2 [11, 15, 58] | 209 – 8791 | 3 [58, 138, 141] | PACE+ [11, 58] ATLS [140] Locally Validated Questionnaire [15] |

| KSA | 48 | 1 [144] | 3547 | 46 [19, 20, 24–27, 36, 38, 41, 42, 44, 48, 51–54, 65, 66, 68, 69, 73, 93, 96, 98, 99, 103, 107, 145–167] | 1 [12] | 30 – 197681 | 3 [38, 157, 167] | ATLS [24, 42, 66, 98, 99, 167] Barriers to Being Active Quiz: CDC website [44] CDC Adolescent Health Survey [27] Electronic Pedometer [19, 20] GPAQ [36, 54, 107, 150] IPAQ [12, 26, 69, 93, 157] KPAS [25] WHO stepwise questionnaire [166] YRBSS and GSHS Questionnaires [167] |

| Kuwait | 15 | 2 [94, 168] | 2280 – 3637 | 12 [37, 49, 79, 97, 169–177] | 1 [15] | 224 – 38611 | 3 [169–171] | The Exercise Pattern Questionnaire [172] Locally Validated Questionnaire [15] |

| Lebanon | 13e | 2 [178, 179] | 1982 – 2286 | 13 [22, 29, 30, 35, 57, 59, 63, 114, 180–186] | 0 | 83 – 2608 | 5 [35, 181, 182, 185, 186] | IPAQ: 2 used a shorter version [35, 181, 182] Self-reported Weekly Activity Checklist [59] |

| Libya | 5e | 2 [187, 188] | 2242 – 3590 | 2 [56, 189] | 2 [11, 15, 58] | 383 – 1300 | 1 [58] | Locally Validated Questionnaire [15] |

| Mauritania | 4 | 2 [190, 191] | 2063 – 2600 | 0 | 2 [12, 13] | 2726 – 212021f | - | IPAQ [12, 13] |

| Morocco | 6e | 1 [192] | 2924 | 5 [38, 61, 62, 75, 84, 85, 105, 193] | 1 [11, 58] | 239 – 2891 | 1 [58] | IPAQ [39] PACE+ [11, 58] |

| Oman | 7e | 2 [94, 194] | 1373 –3468 | 5 [33, 71, 195–197] | 2 [11, 58, 198] | 10 – 5409 | 2 [58, 195] | GPAQ [33] GSHS Questionnaire [197] IPAQ [196] LASA Physical Activity Questionnaire [197] PACE+ [11, 58] WHO Health Behavior in School Children [196] |

| Palestine | 11 | 2 [126, 199, 200] | 1908 – 6957 | 8 [55, 77, 86, 100, 201–204] | 1 [15] | 16 – 8885 | 1 [202] | MESA [204] Locally Validated Questionnaire [15] |

| Qatar | 10e | 2 [205, 206] | 2021 – 2496 | 9 [23, 40, 207–214] | 0 | 340 – 2467 | 1 [214] | GPAQ [214] |

| Somalia | 1 | 0 | - | 1 [215] | 0 | 173 | - | - |

| Sudan | 3 | 2 [216, 217] | 1573 – 2211 | 1 [218] | 0 | 1200 | - | - |

| Syria | 4 | 1 [219] | 3102 | 2 [92, 220, 221] | 1 [15] | 1168-2037 | - | Locally Validated Questionnaire [15] |

| Tunisia | 12e | 1 [222] | 2870 | 9 [31, 32, 43, 76, 223–228] | 4 [11–13, 58, 131] | 10 – 17789 | 2 [43, 223] | IPAQ [12, 13, 228], (including 1 short version) PACE+ [11] Locally Validated questionnaire [31, 43, 223, 224] |

| UAE | 15e | 1 [229] | 2581 | 11 [28, 45, 47, 67, 78, 83, 96, 230–233] | 4 [11–13, 15, 58] | 20 – 9918 | 1 [58] | Health Promoting Lifestyle Profile [47] IPAQ: 3 used shorter version [12, 13, 78, 83] PACE+ [11, 58] Locally Validated Questionnaire [15] |

| Yemen | 1e | 1 [234] | 1175 | 0 | 1 [11] | 568 | 1 [11] | PACE+ [11] |

aWHO-STEPS and GSHS used GPAQ and PACE+ respectively to assess physical inactivity

bThis column indicates whether some studies used internationally or locally standardized/validated instruments, with the reference number in brackets; where not indicated, the assessment of physical activity was either not specified or based on a single question

cATLS: Arab Teens Lifestyle Study – GSHS: Global School-based Student Health survey – IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire – KPAS: Kaiser Physical Activity Survey –LASA: Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam – MESA: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis questionnaire – PACE+: Patient-Centered Assessment and Counseling for Exercise Plus Nutrition – YRBSS: The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

dFor multi-country studies where the information on sample size was not available for each country, we included the pooled sample size.

eA number of journal articles are based on WHO surveys (STEPS and GSHS)

STEPS and GSHS use standardized instruments, namely the Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) and the Patient-Centered Assessment and Counseling for Exercise Plus Nutrition (PACE+) respectively, but only 38/143 journal articles referred to studies that used validated instruments. About half of these used internationally validated tools, such as the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), the GPAQ or the PACE+; others used regionally or nationally validated questionnaires. Two studies used electronic pedometers [19, 20]. The majority of studies (112/157) simply used respondents’ reports. Only five studies followed the WHO’s recommendations regarding the multi-dimensional categorization of physical activity into work, active transportation, household and family, and leisure-time activities; the questionnaires that follow this recommendation include the long version of IPAQ, the GPAQ, and the Kaiser Physical Activity Survey (KPAS).

Prevalence of physical inactivity

Tables 2 and 3 present the prevalence of physical inactivity among adults; Table 2 summarizes data from WHO-STEPS surveys and Table 3 presents results of journal articles. Among adults, the prevalence of physical inactivity defined as performing less than 600 MET-minute per week, exceeded 40% in all Arab countries except for Comoros (21%), Egypt (32%) Jordan (5%); it reached 68% in KSA (national) and 87% in Sudan (subnational).

Table 2.

Prevalence of physical inactivity among adults based on data from WHO-STEPS surveys

| Countrya | Year of study | Age range | Sample size | Prevalence of Physical inactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National samples | ||||

| Comoros | 2011 | 25-64 | 5556 | 20.1 |

| Egypt | 2011-2012 | 15-64 | 5300 | 32.1 |

| Jordan | 2007 | 18+ | 3654 | 5.2 |

| Iraq | 2015 | 18+ | 4120 | 47.0 |

| Kuwait | 2014 | 18-69 | 4391 | 62.6 |

| Libya | 2009 | 25-64 | 3590 | 43.9 |

| Lebanon | 2008 | 25-64 | 1982 | 45.8 |

| Palestine | 2010-2011 | 15-64 | 6957 | 46.5 |

| Qatar | 2012 | 18-64 | 2496 | 45.9 |

| Saudi Arabia | 2005 | 25-64 | 3547 | 67.6 |

| Subnational samples | ||||

| Algeria | 2003 | 25-64 | 4102 | 40.7 |

| Mauritania | 2006 | 25-64 | 1971b | 51.3 |

| Sudan | 2005-2006 | 25-64 | 1573 | 86.8 |

aFor Bahrain and Oman, surveys were available but no total physical inactivity prevalence could be retrieved; specific prevalence of work, transportation, and leisure time were 71.9%, 63.9%, and 57.1%., respectively for Bahrain and 6.4%, 30.1%, and 53.8% for Oman

bSample size was calculated for age group (25-64) from numbers provided in the report

Table 3.

Prevalence of physical inactivity among adults based on findings from published literature

| Country | First author, year (year of study) | Source | Definition | Instrument | Prevalence (%) | Age range | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National samples | |||||||

| Comoros | Guthold, 2008 (2002-2003) | World Health Survey | <600 MET-minutes/week | IPAQ | 2.7 | 18-69 | 1492 |

| Jordan | Zindah, 2008 (2004) | Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System | Not engaging in moderate activity (resulting in light sweating, small increases in breathing or heart rate. | NA | 51.8 | 18+ | 710 |

| Kuwait | Ahmed, 2013 (2002-2009) | National Nutrition Surveillance Data | No deliberate non-work related exercise outside the home such as walking, running or cycling | NA | 68.4 | 20+ | 32811 |

| Al-Zenki, 2012 (2008-2009) | NA | Neither moderately nor very activea | NA | 77.1 | 20+ | 765 | |

| Alarouj, 2013 (NA) | NA | Neither moderate nor vigorous physical activitya | NA | 63.0 | 20-65 | 1970 | |

| KSA | Al-Baghli, 2008 (2004-2005) | NA | No physical activity or mild physical activity (ordinary housework, walking) | NA | 79.2 | 30+ | 197681 |

| Al-Nozha, 2007 (1995-2000) | Coronary Artery Disease in Saudis Study (CADISS) | <600 MET-minutes/week | NA | 96.1 | 30-70 | 17395 | |

| Memish, 2014 (2013) | Saudi Health Information Survey | Neither moderate nor vigorous physical activitya | IPAQ | 69.1 | 15+ | 10735 | |

| Lebanon | Farah, 2015 (2013-2014) | NA | Neither moderate-intensity physical activity for at least 150 min per week or vigorous intensity physical activity for 75 min at least per week | NA | 76.0 | 40+ | 1515 |

| Tohme, 2005 (2003-2004) | NA | Less than 30 min of physical exercise | NA | 40.3 | 30+ | 954 | |

| Mauritania | Guthold, 2008 (2002-2003) | World Health Survey | <600 MET-minutes/week | IPAQ | 61.9 | 18-49 | 1492 |

| Morocco | El Rhazi, 2011 (2008) | NA | Less than 30 min per day | 38.7 | 18+ | 2620 | |

| Najdi, 2011 (2008) | NA | <3METs | IPAQ | 16.5 | 18-99 | 2613 | |

| Palestine | Baron-Epel, 2005 (2002-2003) | KAP and EUROCHIS& | Exercising less than once per week for at least 20 consecutive minutesb | NA | 62.8 | 21+ | 1826c |

| Tunisia | Guthold, 2008 (2002-2003) | World Health Survey | <600 MET-minutes/week | IPAQ | 14.6 | 18-69 | 4332 |

| UAE | Guthold, 2008 (2002-2003) | World Health Survey | <600 MET-minutes/week | IPAQ | 43.2 | 18-69 | 1104 |

| Subnational samplesd | |||||||

| Bahrain | Al-Mahroos, 2001 (NA) | NA | <1 km walking | WHO Heart and Health Questionnaire | 77.5 | 40-69 | 2013 |

| Hamadeh, 2000 (NA) | NA | No exercise | NA | 89.1 | 30-79 | 516 | |

| Egypt | Abolfotouh, 2007 (2002-2003) | NA | No non-vigorous physical activity for at least 20 minutes or 3 times per week | NA | 33.8 | 17-25 | 600 |

| Kamel, 2013 (2010-2011) | NA | NA | NA | 63.8 | 60+ | 340 | |

| Mahfouz, 2014 (2011) | NA | No exercise | NA | 78.3 | NA | 300 | |

| Jordan | Centers for Disease, Control, Prevention, 2003 (2002) | Jordan Behavioral Risk Factor Survey | Less than having moderate: activity that caused light sweating and small increases in heart rate or breathing for 30 minutes | NA | 47.4 | 18+ | 8791 |

| Mohannad, 2008 (2002) | NA | No activity that caused light sweating and small increases in heart rate or breathing | NA | 58.7 | 40+ | 3083 | |

| Kulwicki, 2001 (NA) | NA | No exercise | NA | 22.5 | 17-93 | 209 | |

| Madanat, 2006 (2003) | NA | <30 mins of physical activity/week | NA | 81.5 | Mean: 21.1 | 431 | |

| KSA | Almurshed, 2009 (2003-2004) | NA | No exercise | NA | 52.0 | 30+ | 50 |

| Al-Quaiz, 2009 (2007) | NA | Not practicing in any regular sport and leisure time physical activity | CDC web site questionnaire | 82.4 | 15-80 | 450 | |

| Al-Senany, 2015 (NA) | NA | Less than one hour weekly activity | NA | 69.0 | 60-90 | 55 | |

| Amin, 2011 (NA) | NA | <600 MET-minutes/week | GPAQ | 48.0 | 18-64 | 2176 | |

| Amin, 2014 (NA) | NA | <30 minutes /≥ 5 days/week | GPAQe | 80.0 | 18-78 | 2127 | |

| Awadalla, 2004 (2012-2013) | NA | Neither vigorous: >6 METs nor moderate: 3-6 METs | IPAQ (short form) | 58.0 | 17-25 | 1257 | |

| Garawi, 2015 (2004-2005) | NA | <600 MET-minutes/week | GPAQ | 67.0 | 15-64 | 4758 | |

| Kuwait | Naser Al-Isa, 2011 (NA)f | NA | Not engaging in regular physical activity | NA | 45.0 | NA | 787 |

| Lebanon | Al-Tannir, 2008 (2007) | NA | Less than 3 days/week | NA | 44.5 | 18+ | 346 |

| Musharrafieh, 2008 (2001) | NA | Physical exercise for <0.5 h/week | NA | 73.6 | Mean: 21.0 | 2013 | |

| Tamim, 2003 (2000-2001) | NA | <3 hours/week | NA | 64.3 | Mean: 21.0 | 1964 | |

| Mauritania | Guthold, 2008 (2002-2003) | World Health Survey | <600 MET-minutes/week | IPAQ | 61.9 | 18-49 | 2726 |

| Palestine | Abdul-Rahim, 2003 (NA) | NA | Occupation-related sedentary-light PA for men AND no exercise for women | NA | 56.2 | 30-65 | 936 |

| Abu-Mourad, 2008 (2005) | NA | No home exercise or sports | NA | 78.0 | 18+ | 956 | |

| Qatar | Al-Nakeeb, 2015 (NA) | NA | <840 MET-min/week | NA | 50. 8g | Mean= 21.2 | 732 |

| Bener, 2004 (2003) | NA | Not walking, cycling at least 30 minutes/day | NA | 55.3 | 25-65 | 1208 | |

| Somalia | Ali, 2015 (2013) | NA | <2 hours/week | NA | 33.5 | 18-29 | 173 |

| Syria | Al Ali, 2011 (2006) | 2nd Aleppo Household Survey | Less than 15 mins/ week of sport or brisk walking | NA | 82.3 | 25+ | 1168 |

| Tunisia | Maatoug, 2009 (2009) | NA | <150 mins/week of moderate level of physical activity | Oxford Health Alliance Community Intervention for Health Project | 44.4 | Mean: 37.9 | 1880 |

| UAE | Abdulle, 2006 (2001-2005) | NA | Less than one hour, <3 times per week | NA | 39.4 | 20-75 | 424h |

| McIlvenny, 2000 (NA) | NA | No regular exercise | NA | 54.0 | 18-94 | 254 | |

| Sabri, 2004 (2001-2002) | NA | < 1 hour/week) of sport | NA | 47.5 | 20-65 | 436 | |

aDefinition of physical activity not specified

bIt includes: walking, running, swimming playing ball games or any other sports activities (combined every day and nearly every day with once or twice a week)

cPrevalence rate for Arabs only

dOne study conducted in Libya by Salam (2012) was excluded from the prevalence table; it includes adolescents and youth (17-24 years) and the prevalence was 65.0%

eCombined Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) version 2.0 with a modified show card based on World Health Organization STEPs survey

fKuwaiti college students

gOnly Qatari students

hOnly normotensives

Among the 102 journal articles on adults, 48 reported on prevalence among both men and women. In most countries, inactivity exceeded 40%; a few studies found lower inactivity, including nationally representative studies in Comoros (3%), Morocco (17%), and Tunisia (15%), and subnational studies in Egypt and Somalia (34%) and Jordan (23%).

Physical inactivity among children/adolescents is presented in Tables 4 and 5, based on GSHS reports (Table 4) and journal articles (Table 5). Prevalence of physical inactivity, defined in GSHS as <60 minutes per day on 5 or more days during the past seven days, is very high, with a low of 65% in Lebanon and a high of 91% in Egypt. Journal articles report similarly high levels of inactivity (>60%) except in KSA (45%) and Tunisia (29%), with smaller studies showing a wide variation within and among countries.

Table 4.

Prevalence of physical inactivity among children/adolescents using data from Global School-based Student Health Surveys (GSHS)a

| Country | Year of study | Age range | Sample size | Total prevalence of physical inactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition: < 60 mins per day on five or more days during the past seven days | ||||

| Iraq | 2012 | 13-15 | 2038 | 80.0 |

| Lebanon | 2011 | 13-15 | 2286 | 65.4 |

| Mauritania | 2010 | 13-15 | 2063 | 83.7 |

| Morocco | 2010 | 13-15 | 2924 | 82.6 |

| Palestine (Gaza Strip) | 2010 | 13-15 | 2677 | 75.8 |

| Palestine (West Bank) | 2010 | 13-15 | 1908 | 81.7 |

| Qatar | 2011 | 13-15 | 2021 | 85.0 |

| Sudan | 2012 | 13-15 | 2211 | 89.0 |

| Syria | 2010 | 13-15 | 3102 | 84.9 |

| UAE | 2010 | 13-15 | 2581 | 72.5 |

| Definition: < 60 mins per day on all 7 days during the past 7 days | ||||

| Djibouti | 2007 | 13-15 | 1777 | 85.1 |

| Egypt | 2006 | 13-15 | 5249 | 90.6 |

| Jordan | 2007 | 13-15 | 2197 | 85.6 |

| Kuwait | 2015 | 13-17 | 3637 | 84.4 |

| Libya | 2007 | 13-15 | 2242 | 83.9 |

| Oman | 2015 | 13-17 | 3468 | 88.3 |

| Tunisia | 2008 | 13-15 | 2870 | 81.5 |

| Yemen | 2008 | 13-15 | 1175 | 84.8 |

aAll based on nationally representative samples

Table 5.

Prevalence of physical inactivity among children/adolescents using data from journal articles

| Country | First author, year | Source | Definition | Questionnaire used | Prevalence (%) | Age range | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National samples | |||||||

| Bahrain | Musaiger, 2014 (2006–2007) | NA | <5days/week of playing sport | NA | 72.1 | 15-18 | 735 |

| Egypt | Salazar-Martinez, 2006 (1997) | NA | Not engaged in sports | NA | 62.3 | 11-19 | 1502 |

| KSA | AlBuhairan, 2015 (NA) | NA | Complete absence of exercise | YRBSS and the GSHS Questionnairesa | 45.2 | Mean: 15.8 | 12575 |

| Oman | Afifi, 2006 (2004) | NA | Engaging in physical activities <once per week, apart from school physical education | 27-item Child Depression Inventory | 66.3 | 14-20 | 5409 |

| Palestine | Al Sabbah, 2007 (2003–2004) | Health Behavior in School-aged Children Survey | < 60 minutes/day, <5/7 days per week | WHO international HBSC questionnaire | 80.0 | 12-18 | 8885 |

| Tunisia | Nouira, 2014 (2009-2010) | NA | NA | Oxford Health Alliance for community intervention for health | 88.1 | 12-14 | 3987 |

| Aounallah-Skhiri, 2012 2005 | NA | < 3 Mets | Locally validated questionnaire | 29.4 | 15-19 | 2870 | |

| Subnational sampleb | |||||||

| Algeria | Abbes, 2016 (2010-2011) | NA | Not engaged in sports | NA | 92.8 | 6-11 | 293 |

| Egypt | Shady, 2015 (NS) | NA | < 4 hours/week | NA | 65.5 | 9-11 | 200 |

| Jordan | Haddad, 2009 (NA) | NA | Not very physically nor moderately active | modified Adolescent Wellness Appraisal (AWA) | 4.0 | 12-17 | 530 |

| KSA | Al-Hazzaa, 2011 (2009-2010) | Arab Teens Lifestyle Study | <1680 METs-min/week | ATLS | 61.9 | 15-19 | 2908 |

| Al-Muhaimeed, 2015 (2012) | NA | Not engaging in sports | NA | 27.3 | 6-10 | 601 | |

| Al-Mutairi, 2015 (2013) | NA | No regular exercise | NA | 31.9 | 15-22 | 426 | |

| Al-Othman, 2012 (2010) | NA | NAc | NA | 15.7 | 6-17 | 331 | |

| Mahfouz, 2011 (2008) | NA | Less than 30 mins of physical exercise during the previous week | CDC Adolescent Health Survey Questionnaire | 34.3 | 11-19 | 1869 | |

| Kuwait | Shehab, 2005 (NA) | NA | Only performing normal daily routine with some recreational activities or walking slowly and doing no structured exercise | NA | 71.3 | 10-18 | 400 |

| Lebanon | Nasreddine, 2014 (2009) | NA | Based on weekly frequency: Neverd | NA | 32.6 | Mean: 13.06 | 868 |

| Palestine | Jildeh, 2011 (2002-2003) | The Health Behavior for School-Aged Children Project (HBSC) | <5 days a week | First Palestinian National Health and Nutrition Survey Questionnaire (2000) | 77.6 | 11-16 | 314 |

| Arar, 2009 (NA) | NA | No extra-curricular (EC) physical activities | NA | 43.3 | 9-11 | 180 | |

| Sudan | Moukhyer, 2008 (2001) | NA | Not engaging in sports activities | NA | 33.4 | 10-19 | 1200 |

aGSHS: Global School-based Student Health survey – YRBSS: The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

bOne study conducted in Lebanon by Shediac-Riskallah (2001) was excluded from the prevalence table as it includes youth (16+ years)

cModerate intensity activities included: playground activities, brisk walking, dancing, and bicycle riding. Higher intensity activities included: ball games, jumping rope, active games involving running and chasing, and swimming

dFrequency and type of activities performed along with duration (number of minutes per week)

Gender differences in physical inactivity

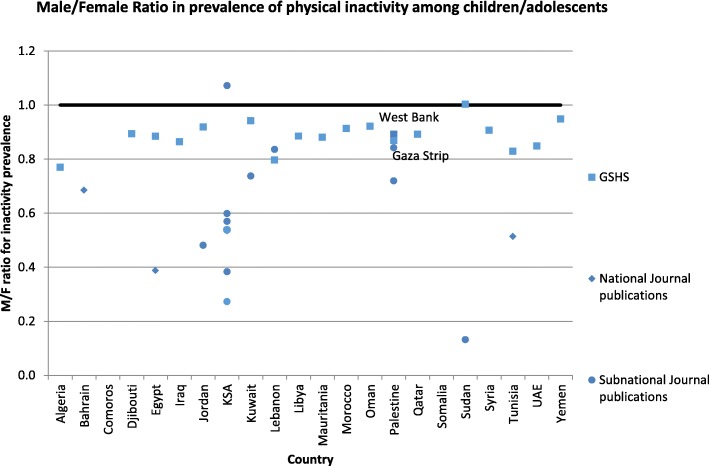

Where physical activity was reported among men/boys and women/girls, we calculated the M/F ratio of the prevalence of physical inactivity. Figures 2 and 3 show gender ratios among adults and children/adolescents respectively. Overall, the prevalence of inactivity was higher among women/girls in all but 9 studies (8 adults and 1 children/adolescents).

Fig. 2.

Gender differences in prevalence of physical inactivity among adults

Fig. 3.

Gender differences in prevalence of physical inactivity among children/adolescents

Socio-demographic and lifestyle determinants

Data from 41 articles about sociodemographic determinants of inactivity were analyzed and results are summarized in Table 6. Inactivity increased with age (18/24 studies), being married (7/10 studies), and urban residence (5/5 studies); it decreased with increased education (14/20 studies) and employment (6/8 studies); parity was positively associated with inactivity in one study. For other sociodemographic determinants, reported associations were inconsistent.

Table 6.

Factors associated with physical inactivity in Arab countries

| Statistical association with physical inactivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Other associations | |

| Agea | [13, 29, 35, 36, 38, 39, 69, 73, 83, 92, 100, 135, 143, 153, 176, 218, 221, 231] | [44, 71, 142] | U shape [63, 202] Curvilinear [41] |

| Marital status | [29, 37, 38, 41, 105, 181, 232] | [42, 79, 221] | |

| Educational levela,b | [35, 54] | [30, 33, 38, 41, 42, 46, 92, 100, 148, 150, 171, 218, 231, 232] | No effect [34, 69, 93] |

| Employmenta | [54, 150] | [30, 33, 36, 92, 183, 232] | |

| SESa,c | [12, 35, 46, 75, 105, 232] | [42, 44, 54, 92, 181] | U shape [83] |

| Urban residence | [35, 36, 43, 77, 150] | ||

| Consuming fruits/vegetables | [33] | ||

| Smokinga | [29–32] | [225] | |

| Alcohol | [30] | ||

| Screen timed | [21–28] | ||

| Overweight/ Obesitye | [22, 24, 29, 33, 35, 37–39] | [30, 40–42] | No effect [43] |

| Chronic medical conditionsa | [29, 34–36] | ||

| Parity | [107] | ||

aThe direction of the association between physical inactivity and some variables was not specified in other studies: age [15, 93, 140, 147, 161], educational level [39, 151], employment [29, 37], SES [26, 31, 34, 39, 140], smoking [30], overweight/obesity [15], and chronic medical conditions [28]

bEducation categorized as iliterate, primary, intermediate, secondary,and university

cSocio-economic status (SES): SES score, resources, income, housing type, wealth, Human Development Index, schooling type, domestic help, car ownership

dScreen time: Television viewing, computer using, video gaming

eThe association between underweight and physical inactivity was mentioned in one study and showed a positive association

Several studies found associations between physical inactivity and lifestyle factors. Predictably, screen time was positively associated with physical inactivity in all eight studies that examined this factor [21–28]. Smoking and alcohol were positively associated with physical inactivity [29–32], while consuming fruits and vegetables was negatively correlated [33]. Four studies found a positive association between physical inactivity and chronic medical conditions [29, 34–36].

The studies we reviewed did not report consistent associations between obesity and physical inactivity: 8/13 found a positive association [22, 24, 29, 33, 35, 37–39], four reported the reverse [30, 40–42] and one showed no effect [43].

Barriers to Physical activity

We examined the subset of studies that investigated barriers to exercise. Some reported reasons were shared with other parts of the world, while others were specific to the Arab region. It is clear that the hot climate of the Arabian Peninsula and Gulf countries limits outdoor physical activity to relatively short seasons and requires special indoor facilities [13, 38, 44–52]. In addition in most countries, the built environment, inadequate public transportation systems, and lack of spaces for walkers or joggers discourage exercise [15, 20, 26, 31, 38, 42, 46, 47, 53–68]. As in other studies, time constraints were mentioned as barriers [15, 26, 28, 30, 31, 40–42, 46, 52, 54, 67, 69–73], in addition to insufficient motivation or interest [25, 26, 34, 44, 46, 54, 71, 73], other priorities [26], and lack of skills [26, 44].

A particularity of the region is the lack of encouragement for physical activity by many parents, who appear to favor educational and spiritual activities over physical activities for their children. Lack of support for physical activity is also noted among friends, peers, and even teachers, in studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan [15, 20, 24–26, 30, 42, 46, 53–55, 64, 66, 68, 71, 74]. Another regionally specific factor relates to gender constraints: even where fitness facilities are available, as is the case in the more affluent countries of the region, accessibility is a problem, particularly for women.

Lower physical activity among women has been attributed to gender norms, including conservative dress that is not suitable for physical activity, the need for women to be chaperoned in public spaces, and the paucity of gender-segregated fitness facilities [15, 28, 62, 64, 67, 71, 75, 76]. In addition, cultural values put a premium on comfort for both genders, physical exertion is avoided, and public spaces such as streets are not considered appropriate for physical activity. Thus, both general norms and gender norms converge to discourage physical activity [15, 27, 31, 41, 45–47, 54, 60, 62–64, 67, 74, 75, 77–86].

Discussion

The diversity of definitions and methods among studies published in journals and the fact that only 43/157 studies used validated instruments hampers comparisons of the prevalence and correlates of physical activity, and it is possible that some of the differences we found are artifactual. Using inactivity instead of activity improves the comparability, but it is clear that harmonizing definitions and measurements and considering the multi-dimensional aspects of physical activity would improve the evidence for the region.

Despite these limitations, it is possible to discern some patterns. The results of this review indicate that throughout the region, levels of physical inactivity are very high. Inactivity among adults is 40% or higher in all but five of the fifteen countries with nationally representative surveys; studies with smaller samples suggest even higher levels of inactivity (>60%). Among children and adolescents, inactivity is alarmingly high, around 80% in all national surveys except Tunisia.

High inactivity among children and adolescents is documented in other regions [87, 88] and is a worldwide problem, but the levels of adult inactivity we found in this review compare very unfavorably with those of other regions. Inactivity levels in Europe, the western Pacific, Africa, and southeast Asia are considerably lower (25%, 34%, 28% and 17% respectively [88–90]); they are even lower in South-East Asia and Africa (15% and 21% respectively); the Americas have lower or similar inactivity levels [88–90]. These high levels of inactivity indicate that social circumstances in many countries of the region do not seem to encourage physical activity. Some comparative analyses across countries in the Arab region and outside it have reported that Muslim countries were more likely to be physically inactive, and seemed to suggest that religion constitutes an obstacle to physical activity [91]. This however is not consistent with the diverse interpretations of religious doctrine in the region, and the fact that there are no grounds for arguing that Islamic doctrine is antithetical to exercise. In addition, there is no evidence linking religious observance to lower activity. The one study that compared Muslims and non-Muslims, conducted in Syria, found no significant differences in physical activity between Muslim Syrians and Syrians belonging to other religious groups [92]. Such research highlights the complex interplay among the multiple factors that hinder physical activity.

Physical and social barriers to exercise have been amply documented in multiple Arab countries: the hot weather discourages walking and exertion outdoors; an unfriendly built environment hinders exercise and promotes a car culture; physical exertion is associated with lower status occupations; a premium is placed on comfort; all these contribute to devaluing and discouraging exercise. That parental preferences favor spiritual and educational, over physical activities, and social gatherings are the main leisure activity further contributes to reducing physical activity and encouraging sedentarity [93, 94].

The combination of physical obstacles and low valuations translates into insufficient interest and motivation to exercise, which are documented in multiple countries [20, 46, 52, 68, 90]. A number of studies [24, 40, 71, 74, 95–101] bring out the clustering of health risks within the studied populations, whereby physical activity is one among a set of lifestyle factors that may include energy dense foods, sweet drinks, sedentariness, and unsafe driving. This suggests that lack of knowledge about healthy behaviors in general contributes to inactivity, and emphasizes the role of social activities that are focused on sedentarity and unhealthy snacking. Interestingly, studies [72] that have probed into perceptions of health behaviors have found these to be limited to hygiene, rest and diet, but not physical activity. Thus a combination of material and cultural factors translates into barriers to physical activity at multiple levels and to a lack of awareness and motivation among the population.

A striking result of this analysis is the consistency of gender differences in physical inactivity: in nearly all (45/53) studies conducted among adults and (31/32) among children/adolescents, prevalence of inactivity was higher among women/girls. While traditional religious norms have been reported to potentially define acceptable behaviors for women and preclude exercising, careful qualitative research [76, 102] shows that these are not insurmountable obstacles. Studies show that some women athletes negotiate their involvement in sports even as they continue to wear Islamic clothing, and that decisions to exercise are influenced by new ideas about healthy lifestyles disseminated by professionals. In addition, some studies [103] suggest that ideas about physical activity can become more positive, and that cultural barriers can be overcome when adequate facilities are available.

Studies on ideas about the body report preferences for heavier shapes, especially for men [104] and ethnographic research indicates that there is a normalization of weight gain with increasing age and with maternal status among women [105, 106]. Such notions of the body likely translate into a lack of motivation to exercise and maintain optimal weight across the life cycle for both sexes, and women are vulnerable to weight gain with successive pregnancies. Women's marginalization in segregated societies [107] further pushes them towards a lifestyle centered on hospitality, excessive food consumption and sedentariness. But research also indicates that ideal body shapes can change as a result of exposure to media, as younger women in several countries of the region seem to have adopted thinner body shape preferences [108]. Ideas about exercise can also be transformed by initiatives that provide information about the link between health and exercise, activities that involve women in sports, and efforts to change societal valuations of exertion—and of women [109].

Some initiatives, inspired by those in other regions [110] are underway: policies have been formulated in Oman and Qatar; healthy lifestyles including exercise have been promoted in Morocco, Bahrain and Palestine [111]; some have reported success in improving physical activity in Dubai [89], and Oman [112], while others, such as school-based interventions [113, 114] in Lebanon and Tunisia did not report improvements in physical activity or reductions in screen time. A closer examination of these interventions’ successes and failures can provide useful lessons for future efforts.

Conclusions

The high levels of inactivity in the region call for considerable efforts to tackle the material and socio-cultural aspects of the cultural context that discourage physical activity. Multi-sectoral efforts are needed, including collaborations among ministries of health, sports, youth and education, as well as wider collaborations that involve sectors such as transport, environment and urban planning [16, 111, 115].

Additional file

Medline search strategy. (DOCX 13 kb)

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by a grant (106981–001) from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) in Canada. The funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

We would like to thank Dr. Regina Guthold of the World Health Organization, for her constructive comments on a previous draft of the manuscript, and Zeina Jamaluddine for assisting with the preparation of the data extraction protocol.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant (106981–001) from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) in Canada. The funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data were extracted from published sources. Data sharing not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ATLS

Arab Teens Lifestyle Study

- DALYs

Disability Adjusted Life Years

- GPAQ

Global Physical Activity Questionnaire

- GSHS

Global School-based Student Health Surveys

- IPAQ

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- KPAS

Kaiser Physical Activity Survey

- KSA

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

- LASA

Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam

- MESA

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis questionnaire

- ODK

Open Data Kit

- PACE+

Patient-Centered Assessment and Counseling for Exercise Plus Nutrition

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- SSCI

Social Sciences Citation Index

- UAE

United Arab Emirates

- WHO STEPS

World Health Organization STEPwise approach to Surveillance

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WHS

World Health Surveys

- YRBSS

The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System

Authors’ contributions

ES drafted the paper and conducted data screening, extraction, analysis and interpretation; CA conducted the search and data screening; CA and HG supervised the work and contributed to data analysis, interpretation and writing. CMO designed the analysis, supervised the work and critically reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12889-018-5472-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Eman Sharara, Email: ess05@mail.aub.edu.

Chaza Akik, Phone: 00961-1 350000, Email: ca36@aub.edu.lb.

Hala Ghattas, Email: hg15@aub.edu.lb.

Carla Makhlouf Obermeyer, Email: carla.makhlouf@univ-amu.fr.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. n.d. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_inactivity/en/. Accessed 16 Feb 2017.

- 2.World Health Organization. Physical activity. 2017. http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/. Accessed Feb 2017.

- 3.Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, Jolliffe J, Noorani H, Rees K, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2004;116(10):682–692. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair SN, Cheng Y, Holder JS. Is physical activity or physical fitness more important in defining health benefits? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6; SUPP):S379–SS99. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aune D, Sen A, Prasad M, Norat T, Janszky I, Tonstad S, et al. BMI and all cause mortality: systematic review and non-linear dose-response meta-analysis of 230 cohort studies with 3.74 million deaths among 30.3 million participants. BMJ. 2016;353:i2156. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fogelholm M. Physical activity, fitness and fatness: relations to mortality, morbidity and disease risk factors. A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2010;11(3):202–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD Compare. IHME, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. 2015. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare. Accessed July 2016.

- 8.Kilpi F, Webber L, Musaigner A, Aitsi-Selmi A, Marsh T, Rtveladze K, et al. Alarming predictions for obesity and non-communicable diseases in the Middle East. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(05):1078–1086. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mokdad AH, Jaber S, Aziz MIA, AlBuhairan F, AlGhaithi A, AlHamad NM, et al. The state of health in the Arab world, 1990–2010: an analysis of the burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. The Lancet. 2014;383(9914):309–320. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tailakh A, Evangelista LS, Mentes JC, Pike NA, Phillips LR, Morisky DE. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, and control in Arab countries: a systematic review. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16(1):126–130. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Subhi LK, Bose S, Al Ani MF. Prevalence of Physically Active and Sedentary Adolescents in 10 Eastern Mediterranean Countries and its Relation With Age, Sex, and Body Mass Index. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12(2):257–265. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumith SC, Hallal PC, Reis RS, Kohl HW., 3rd Worldwide prevalence of physical inactivity and its association with human development index in 76 countries. Prev Med. 2011;53(1-2):24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guthold R, Ono T, Strong KL, Chatterji S, Morabia A. Worldwide variability in physical inactivity a 51-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(6):486–494. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mabry R, Koohsari MJ, Bull F, Owen N. A systematic review of physical activity and sedentary behaviour research in the oil-producing countries of the Arabian Peninsula. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1003. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3642-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musaiger AO, Al-Mannai M, Tayyem R, Al-Lalla O, Ali EY, Kalam F, et al. Perceived barriers to healthy eating and physical activity among adolescents in seven Arab countries: a cross-cultural study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:232164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Reis RS, Salvo D, Ogilvie D, Lambert EV, Goenka S, Brownson RC et al. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1337–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, Boers M, Andersson N, Hamel C, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Hazzaa HM. Pedometer-determined physical activity among obese and non-obese 8- to 12-year-old Saudi schoolboys. J Physiol Anthropol. 2007;26(4):459–465. doi: 10.2114/jpa2.26.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Rasheedi AA. Adiposity and physical activity levels among preschool children in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal. 2007;28(5):766–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salazar-Martinez E, Allen B, Fernandez-Ortega C, Torres-Mejia G, Galal O, Lazcano-Ponce E. Overweight and obesity status among adolescents from Mexico and Egypt. Arch Med Res. 2006;37(4):535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chacar HR, Salameh P. Public schools adolescents' obesity and growth curves in Lebanon. J Med Liban. 2011;59(2):80–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bener A, Al-Mahdi HS, Vachhani PJ, Al-Nufal M, Ali AI. Do excessive internet use, television viewing and poor lifestyle habits affect low vision in school children? J Child Health Care. 2010;14(4):375–385. doi: 10.1177/1367493510380081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Nakeeb Y, Lyons M, Collins P, Al-Nuaim A, Al-Hazzaa H, Duncan MJ, et al. Obesity, physical activity and sedentary behavior amongst British and Saudi youth: a cross-cultural study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(4):1490–1506. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9041490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alquaiz AM, Kazi A, Qureshi R, Siddiqui AR, Jamal A, Shaik SA. Correlates of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Scores in Women in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Women Health. 2015;55(1):103–117. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.972020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awadalla NJ, Aboelyazed AE, Hassanein MA, Khalil SN, Aftab R, Gaballa II, et al. Assessment of physical inactivity and perceived barriers to physical activity among health college students, south-western Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20(10):596–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahfouz AA, Shatoor AS, Khan MY, Daffalla AA, Mostafa OA, Hassanein MA. Nutrition, physical activity, and gender risks for adolescent obesity in Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(5):318–322. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.84486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ali HI, Baynouna LM, Bernsen RM. Barriers and facilitators of weight management: perspectives of Arab women at risk for type 2 diabetes. Health Soc Care Community. 2010;18(2):219–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Tannir M, Kobrosly S, Itani T, El-Rajab M, Tannir S. Prevalence of physical activity among Lebanese adults: a cross-sectional study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(3):315–320. doi: 10.1123/jpah.6.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musharrafieh U, Tamim HM, Rahi AC, El-Hajj MA, Al-Sahab B, El-Asmar K, et al. Determinants of university students physical exercise: a study from Lebanon. Int J Public Health. 2008;53(4):208–213. doi: 10.1007/s00038-008-7037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aounallah-Skhiri H, Ben Romdhane H, Maire B, Elkhdim H, Eymard-Duvernay S, Delpeuch F, et al. Health and behaviours of Tunisian school youth in an era of rapid epidemiological transition. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(5):1201–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maatoug J, Harrabi I, Hmad S, Belkacem M, Al'absi M, Lando H, et al. Clustering of risk factors with smoking habits among adults, Sousse, Tunisia. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E211. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mabry R, Winkler E, Reeves M, Eakin E, Owen N. Correlates of Omani adults' physical inactivity and sitting time. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(1):65. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hallaj FA, El Geneidy MM, Mitwally HH, Ibrahim HS. Activity patterns of residents in homes for the elderly in Alexandria, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(11):1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sibai AM, Costanian C, Tohme R, Assaad S, Hwalla N. Physical activity in adults with and without diabetes: from the 'high-risk' approach to the 'population-based' approach of prevention. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1002. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amin TT, Al Khoudair AS, Al Harbi MA, Al Ali AR. Leisure time physical activity in Saudi Arabia: prevalence, pattern and determining factors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(1):351–360. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.1.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Isa AN, Campbell J, Desapriya E, Social WN. Health Factors Associated with Physical Activity among Kuwaiti College Students. J Obes. 2011;2011:512363–512366. doi: 10.1155/2011/512363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Nozha MM, Al-Hazzaa HM, Arafah MR, Al-Khadra A, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Maatouq MA, et al. Prevalence of physical activity and inactivity among Saudis aged 30-70 years. A population-based cross-sectional study. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(4):559–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Najdi A, El Achhab Y, Nejjari C, Norat T, Zidouh A, El Rhazi K. Correlates of physical activity in Morocco. Prev Med. 2011;52(5):355–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Nakeeb Y, Lyons M, Dodd LJ, Al-Nuaim A. An Investigation into the Lifestyle, Health Habits and Risk Factors of Young Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(4):4380–4394. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120404380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Refaee SA, Al-Hazzaa HM. Physical activity profile of adult males in Riyadh City. Saudi Med J. 2001;22(9):784–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khalaf A, Ekblom O, Kowalski J, Berggren V, Westergren A, Al-Hazzaa H. Female university students' physical activity levels and associated factors--a cross-sectional study in southwestern Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(8):3502–3517. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10083502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aounallah-Skhiri H, Romdhane HB, Traissac P, Eymard-Duvernay S, Delpeuch F, Achour N, et al. Nutritional status of Tunisian adolescents: associated gender, environmental and socio-economic factors. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(12):1306–1317. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.AlQuaiz AM, Tayel SA. Barriers to a healthy lifestyle among patients attending primary care clinics at a university hospital in Riyadh. Ann Saudi Med. 2009;29(1):30–35. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.51818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baglar R. "Oh God, save us from sugar": an ethnographic exploration of diabetes mellitus in the United Arab Emirates. Med Anthropol. 2013;32(2):109–125. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2012.671399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.El-Gilany AH, Badawi K, El-Khawaga G, Awadalla N. Physical activity profile of students in Mansoura University, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(8):694–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim HJ, Choi-Kwon S, Kim H, Park YH, Koh CK. Health-promoting lifestyle behaviors and psychological status among Arabs and Koreans in the United Arab Emirates. Res Nurs Health. 2015;38(2):133–141. doi: 10.1002/nur.21644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Memish ZA, Jaber S, Mokdad AH, AlMazroa MA, Murray CJL, Al Rabeeah AA, et al. Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 1990-2010. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014;11 10.5888/pcd11.140176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Musaiger AO, Al-Kandari FI, Al-Mannai M, Al-Faraj AM, Bouriki FA, Shehab FS, et al. Perceived barriers to weight maintenance among university students in Kuwait: the role of gender and obesity. Environ Health Prev Med. 2014;19(3):207–214. doi: 10.1007/s12199-013-0377-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahim HFA, Sibai A, Khader Y, Hwalla N, Fadhil I, Alsiyabi H, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the Arab world. Lancet. 2014;383(9914):356–367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Al-Baghli NA, Al-Ghamdi AJ, Al-Turki KA, El-Zubaier AG, Al-Ameer MM, Overweight A-BFA. obesity in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(9):1319–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Mutairi RL, Bawazir AA, Ahmed AE, Jradi H. Health Beliefs Related to Diabetes Mellitus Prevention among Adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2015;15(3):e398–e404. doi: 10.18295/squmj.2015.15.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Nakeeb Y, Duncan MJ, Al-Sobayel HI, Abahussain NA, Musaiger AO, et al. A cross-cultural comparison of health behaviors between Saudi and British adolescents living in urban areas: gender by country analyses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(12):6701–6720. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10126701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amin TT, Suleman W, Ali A, Gamal A, Al Wehedy A. Pattern, prevalence, and perceived personal barriers toward physical activity among adult Saudis in Al-Hassa, KSA. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(6):775–784. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Arar KH, Rigbi A. 'To participate or not to participate?'status and perception of physical education among Muslim Arab-Israeli secondary school pupils. Sport Educ Soc. 2009;14(2):183–202. [Google Scholar]

- 56.El Ansari W, Khalil K, Crone D, Stock C. Physical activity and gender differences: correlates of compliance with recommended levels of five forms of physical activity among students at nine universities in Libya. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2014;22(2):98–105. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fazah A, Jacob C, Moussa E, El-Hage R, Youssef H, Delamarche P. Activity, inactivity and quality of life among Lebanese adolescents. Pediatr Int. 2010;52(4):573–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guthold R. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Among Schoolchildren: A 34-Country Comparison. J Pediatr. 2010;157(1):43–9.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jabre P, Sikias P, Khater-Menassa B, Baddoura R, Awada H. Overweight children in Beirut: prevalence estimates and characteristics. Child: Care, Health & Development. 2005;31(2):159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nsour M, Mahfoud Z, Kanaan MN, Prevalence BA. predictors of nonfatal myocardial infarction in Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(4):818–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rguibi M, Belahsen R. Overweight and obesity among urban Sahraoui women of South Morocco. Ethn. Dis. 2004;14(4):542-547. [PubMed]

- 62.Rguibi M, Belahsen R. High blood pressure in urban Moroccan Sahraoui women. J Hypertens. 2007;25(7):1363–1368. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280f31b83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Soweid RA, Farhat TM, Yeretzian J. Adolescent health-related behaviors in postwar Lebanon: findings among students at the American University of Beirut. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2001;20(2):115–131. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Madanat H, Merrill RM. Motivational factors and stages of change for physical activity among college students in Amman, Jordan. Promot Educ. 2006;13(3):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alam AA. Obesity among female school children in North West Riyadh in relation to affluent lifestyle. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(8):1139–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Al-Hazzaa HM, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI, Qahwaji DM, Musaiger AO. Physical activity, sedentary behaviors and dietary habits among Saudi adolescents relative to age, gender and region. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:140. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berger G, Peerson A. Giving young Emirati women a voice: participatory action research on physical activity. Health Place. 2009;15(1):117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alsubaie AS, Omer EO. Physical Activity Behavior Predictors, Reasons and Barriers among Male Adolescents in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: Evidence for Obesogenic Environment. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2015;9(4):400–408. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Al-Hazzaa HM. Health-enhancing physical activity among Saudi adults using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(1):59–64. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007184299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ammouri AA, Neuberger G, Nashwan AJ, Al-Haj AM. Determinants of self-reported physical activity among Jordanian adults. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(4):342–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mabry RM, Al-Busaidi ZQ, Reeves MM, Owen N, Eakin EG. Addressing physical inactivity in Omani adults: perceptions of public health managers. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(3):674–681. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012005678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mahasneh SM. Health perceptions and health behaviours of poor urban Jordanian women. J Adv Nurs. 2001;36(1):58–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al-Gelban KS. Dietary habits and exercise practices among the students of a Saudi Teachers' Training College. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(5):754–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Abolfotouh MA, Bassiouni FA, Mounir GM, Fayyad R. Health-related lifestyles and risk behaviours among students living in Alexandria University Hostels. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13(2):376–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.El Rhazi K, Nejjari C, Zidouh A, Bakkali R, Berraho M, Barberger Gateau P. Prevalence of obesity and associated sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in Morocco. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(1):160–167. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010001825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lachheb M. Religion in practice. The veil in the sporting space in Tunisia. Social Compass. 2012;59(1):120–135. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abdul-Rahim HF, Holmboe-Ottesen G, Stene LC, Husseini A, Giacaman R, Jervell J, et al. Obesity in a rural and an urban Palestinian West Bank population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(1):140–146. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Al Junaibi A, Abdulle A, Sabri S, Hag-Ali M, Nagelkerke N. The prevalence and potential determinants of obesity among school children and adolescents in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37(1):68–74. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Al-Kandari F, Vidal VL. Correlation of the health-promoting lifestyle, enrollment level, and academic performance of College of Nursing students in Kuwait. Nurs Health Sci. 2007;9(2):112–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gharaibeh M, Al-Ma'aitah R, Al Jada N. Lifestyle practices of Jordanian pregnant women. Int Nurs Rev. 2005;52(2):92–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haddad LG, Owies A, Mansour A. Wellness appraisal among adolescents in Jordan: a model from a developing country: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Health Promot Int. 2009;24(2):130–139. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Musaiger AO, Al-Roomi K, Bader Z. Social, dietary and lifestyle factors associated with obesity among Bahraini adolescents. Appetite. 2014;73:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Ali H, Harrison G, Yeatts K, El Sadig M, et al. Nutrition transition in the United Arab Emirates. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(12):1328–1337. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rguibi M, Belahsen R. Fattening practices among Moroccan Saharawi women. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12(5):619–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rguibi M, Belahsen R. Metabolic syndrome among Moroccan Sahraoui adult Women. Am J Hum Biol. 2004;16(5):598–601. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sirdah MM, Al Laham NA, Abu Ghali AS. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated socioeconomic and demographic factors among Palestinian adults (20-65 years) at the Gaza Strip. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2011;5(2):93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Moraes ACF, Guerra PH, Menezes PR. The worldwide prevalence of insufficient physical activity in adolescents; a systematic review. Nutr Hosp. 2013;28(3):575–584. doi: 10.3305/nh.2013.28.3.6398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sallis JF, Bull F, Guthold R, Heath GW, Inoue S, Kelly P, et al. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. The Lancet. 2016; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.World Health Organization. Prevalence of insufficient physical activity. 2016. http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/physical_activity_text/en/.

- 90.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U, et al. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kahan D. Adult physical inactivity prevalence in the Muslim world: Analysis of 38 countries. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Al Ali R, Rastam S, Fouad FM, Mzayek F, Maziak W. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors among adults in Aleppo, Syria. Int J Public Health. 2011;56(6):653–662. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, Hagstromer M, Craig CL, Bull FC, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of sitting. A 20-country comparison using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.World Health Organization. Global School-based Student Health Survey Oman 2015 Fact Sheet 2015.

- 95.Abdulle AM, Nagelkerke NJ, Abouchacra S, Pathan JY, Adem A, Obineche EN. Under- treatment and under diagnosis of hypertension: a serious problem in the United Arab Emirates. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Abou-Zeid AH, Hifnawy TM, Abdel Fattah M. Health habits and behaviour of adolescent schoolchildren, Taif, Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15(6):1525–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Al-Haifi AR, Al-Fayez MA, Al-Athari BI, Al-Ajmi FA, Allafi AR, Al-Hazzaa HM, et al. Relative contribution of physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and dietary habits to the prevalence of obesity among Kuwaiti adolescents. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(1):6–13. doi: 10.1177/156482651303400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Al-Hazzaa HM, Abahussain NA, Al-Sobayel HI, Qahwaji DM, Musaiger AO. Lifestyle factors associated with overweight and obesity among Saudi adolescents. Bmc Public Health. 2012;12 10.1186/1471-2458-12-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Sobayel HI, Abahussain NA, Qahwaji DM, Alahmadi MA, Musaiger AO. Association of dietary habits with levels of physical activity and screen time among adolescents living in Saudi Arabia. J Human Nut Dietetics. 2014;27(Suppl 2):204–213. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Al Sabbah H, Vereecken C, Kolsteren P, Abdeen Z, Maes L. Food habits and physical activity patterns among Palestinian adolescents: findings from the national study of Palestinian schoolchildren (HBSC-WBG2004) Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(7):739–746. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007665501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hamrani A, Mehdad S, El Kari K, El Hamdouchi A, El Menchawy I, Belghiti H, et al. Physical activity and dietary habits among Moroccan adolescents. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(10):1793–1800. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Donnelly TT, Al Suwaidi J, Al Enazi NR, Idris Z, Albulushi AM, Yassin K, et al. Qatari Women Living With Cardiovascular Diseases—Challenges and Opportunities to Engage in Healthy Lifestyles. Health Care Women Int. 2012;33(12):1114–1134. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.712172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Samara A, Nistrup A, Al-Rammah TY, Aro AR. Lack of facilities rather than sociocultural factors as the primary barrier to physical activity among female Saudi university students. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:279–286. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S80680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pope JHG, Gruber AJ, Mangweth B, Bureau B, deCol C, Jouvent R, et al. Body image perception among men in three countries. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(8):1297–1301. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Batnitzky A. Obesity and household roles: gender and social class in Morocco. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30(3):445–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Batnitzky AK. Cultural constructions of “obesity”: Understanding body size, social class and gender in Morocco. Health Place. 2011;17(1):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Garawi F, Ploubidis GB, Devries K, Al-Hamdan N, Uauy R. Do routinely measured risk factors for obesity explain the sex gap in its prevalence? Observations from Saudi Arabia. Bmc Public Health. 2015;15. 10.1186/s12889-015-1608-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Trainer SS. Body image, health, and modernity: Women’s perspectives and experiences in the United Arab Emirates. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2010;22(3_suppl):60S–67S. doi: 10.1177/1010539510373127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Devi S. Jumping cultural hurdles to keep fit in the Middle East. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1267. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31709-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.ParticipACTION. It's time for Canada to sit less and move more. 2016. https://www.participaction.com/. Accessed Mar 2017.

- 111.World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Promoting physical activity in the Eastern Mediterranean Region through a life-course approach.2014.

- 112.World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. The Nizwa healthy lifestyles project, Oman. In: Physical activity - Case studies 2016. http://www.emro.who.int/health-education/physical-activity-case-studies/the-nizwa-healthy-lifestyles-project-oman.html. Accessed Aug 2016

- 113.Harrabi I, Maatoug J, Gaha M, Kebaili R, Gaha R, Ghannem H. School-based Intervention to Promote Healthy Lifestyles in Sousse, Tunisia. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35(1):94–99. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Habib-Mourad C, Ghandour LA, Moore HJ, Nabhani-Zeidan M, Adetayo K, Hwalla N, et al. Promoting healthy eating and physical activity among school children: findings from Health-E-PALS, the first pilot intervention from Lebanon. Bmc Public Health. 2014;14 10.1186/1471-2458-14-940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Gardner B, Smith L, Lorencatto F, Hamer M, Biddle SJ. How to reduce sitting time? A review of behaviour change strategies used in sedentary behaviour reduction interventions among adults. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10(1):89–112. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1082146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.World Health Organization. Algeria STEPS Survey 2003 Fact Sheet 2003.

- 117.World Health Organization. Global School-based Student Health Survey Algeria 2011 Fact Sheet 2011.

- 118.Abbes MA, Bereksi-Reguig K. Risk factors for obesity among school aged children in western Algeria: results of a study conducted on 293 subjects. Tunis Med. 2016;94(1):23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.World Health Organization. Report of the National Non-communicable Diseases Step-wise Survey 2007.

- 120.Al-Mahroos F, Al-Roomi K. Obesity among adult Bahraini population: Impact of physical activity and educational level. Ann Saudi Med. 2001;21(3-4):183–187. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2001.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hamadeh RR, Musaiger AO. Lifestyle patterns in smokers and non-smokers in the state of Bahrain. Nicotine Tob Res. 2000;2(1):65–69. doi: 10.1080/14622200050011312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Borgan SM, Jassim GA, Marhoon ZA, Ibrahim MH. The lifestyle habits and wellbeing of physicians in Bahrain: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:655. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1969-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.World Health Organization. STEPS 2011 Note de synthèse 2011.

- 124.World Health Organization. Global School-based Student Health Survey Djibouti 2007 Fact Sheet 2007.

- 125.World Health Organization. Egypt STEPS Survey 2011-12 2012.

- 126.World Health Organization. Global School-based Student Health Survey Egypt 2011 Fact Sheet 2011.