Significance

Pairs of spins in molecular materials have attracted significant interest as intermediates in photovoltaic devices and light-emitting diodes. However, isolating the local spin and electronic environments of such intermediates has proved challenging due to the complex structures in which they reside. Here we show how exchange coupling can be used to select and characterize multiple coexisting pairs, enabling joint measurement of their exchange interactions and optical profiles. We apply this to spin-1 pairs formed by photon absorption whose coupling gives rise to total-spin and 2-pair configurations with drastically different properties. This presents a way of identifying the molecular conformations involved in spin-pair processes and generating design rules for more effective use of interacting spins.

Keywords: organic semiconductors, exchange coupling, triplet excitons, singlet fission, organic spintronics

Abstract

From organic electronics to biological systems, understanding the role of intermolecular interactions between spin pairs is a key challenge. Here we show how such pairs can be selectively addressed with combined spin and optical sensitivity. We demonstrate this for bound pairs of spin-triplet excitations formed by singlet fission, with direct applicability across a wide range of synthetic and biological systems. We show that the site sensitivity of exchange coupling allows distinct triplet pairs to be resonantly addressed at different magnetic fields, tuning them between optically bright singlet () and dark triplet quintet () configurations: This induces narrow holes in a broad optical emission spectrum, uncovering exchange-specific luminescence. Using fields up to 60 T, we identify three distinct triplet-pair sites, with exchange couplings varying over an order of magnitude (0.3–5 meV), each with its own luminescence spectrum, coexisting in a single material. Our results reveal how site selectivity can be achieved for organic spin pairs in a broad range of systems.

Spin pairs control the behavior of systems ranging from quantum circuits to photosynthetic reaction centers (1, 2). In molecular materials, such pairs mediate a diverse range of processes such as light emission, charge separation, and energy harvesting (3–5). The relevant spin pair may consist of two spin-1/2 particles, in the form of either a bound exciton or a weakly coupled electron–hole pair, or spin-1 pairs, which have recently emerged as alternatives for efficient light emission and harvesting (6–9). A key challenge in understanding and using such pairs is accessing the local molecular environments which support their generation and evolution within more complex structures, information which could ultimately lead to active control of their properties.

Here we demonstrate that the joint dependence of spin and electronic interactions on pair conformation provides a handle to separate such states and extract their discrete environments from a broader energetic landscape. We apply this technique to measure distinct triplet pairs formed by singlet fission (Fig. 1A), a process which generates two spin excitons from a photogenerated singlet exciton and is of great current interest for solar energy conversion (10–12). We simultaneously extract the exchange energies and optical spectra of three different triplet-pair sites within the same material. Using a magnetic field, we tune different triplet pairs into excited-state avoided crossings, which we detect as spectral holes in an inhomogeneously broadened photoluminescence (PL) spectrum. This enables combined spin and optical characterization of these states: The fields required to induce level crossings directly measure the set of pair exchange-coupling strengths, while the spectral holes provide narrow, spin-specific optical profiles of the states. We extract multiple triplet-pair states with exchange couplings varying by an order of magnitude and decouple their distinct luminescence spectra from an otherwise inhomogeneously broadened background, reaching subnanometer spectral linewidths. Our results reveal more means of determining structure–function relations of coupled spins and identify unambiguous pair signatures. This approach is directly applicable to a range of organic systems: from electron–hole pairs in next-generation light-emitting diodes to coupled excitons in artificial and naturally occurring light harvesters.

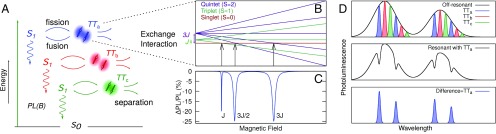

Fig. 1.

Selective addressing of exchange-coupled triplet–exciton pairs. (A) Schematic of spin-pair generation by singlet fission for an ensemble of pair sites with different exchange interactions. Photon absorption generates a spin-singlet exciton (), which can radiatively decay, producing PL, or undergo fission into a pair of triplet excitons . Fusion of this triplet pair reforms the singlet exciton, while dissociation destroys it. (B and C) Triplet-pair level anticrossings for a single exchange energy. A magnetic field tunes optically dark triplet or quintet spin sublevels into near degeneracy with the bright singlet state, resulting in selective reductions in the PL at fields proportional to the exchange interaction . . (D) The magnetic-field–induced anticrossings create spectral holes linked to a specific triplet pair. This enables the narrow associated emission profiles of triplet pairs with different exchange interactions to be extracted.

Results and Discussion

Method for Selectively Addressing Exchange-Coupled Triplets.

Despite their key role in light emitters and harvesters, triplet pairs have only recently been discovered to form exchange-coupled states (13–17)—we start by outlining how such states can be selectively addressed to provide a site-specific measurement of their exchange interactions and associated optical spectra. Here we describe the specific case of singlet fission, but emphasize that the approach can be directly translated to many other molecular systems since spin-conserving transitions are a general feature of such materials.

Fig. 1A outlines the process of triplet-pair generation by singlet fission, where both fission and the subsequent fusion process are spin conserving. This makes the spectral regions associated with triplet pairs sensitive to their spin states, which can be resonantly tuned with an external magnetic field (Fig. 1B). For strongly exchange-coupled triplets, the eigenstates at zero magnetic field consist of the pure singlet (), triplet ( = 1), and quintet () pairings of the two particles. Due to its singlet precursor, fission selectively populates the triplet-pair configuration, which is energetically separated from the optically inactive triplet or quintet states due to the exchange interaction. Application of a magnetic field enables these triplet or quintet states to be tuned into resonance with the optically active singlet-pair state when the Zeeman energy matches the singlet–triplet or singlet–quintet exchange splitting. At these field positions, bright singlet-pair states become hybridized with a dark triplet or quintet-pair state, manifesting as a resonant reduction in the relevant PL spectral window (Fig. 1C) (16–18).

Crucially, the crossings directly address pairs with a specific exchange coupling. For an exchange interaction , where are the spin operators for the two triplets, the resonances occur at (singlet-triplet crossing) and , (singlet–quintet crossings), giving a direct measurement of the exchange. (Here we take ; SI Appendix, VI. Spin Hamiltonian and Sign of J.) Furthermore, only the emission linked to the resonant triplet pair will be diminished at each level crossing. The magnetic-field resonances will therefore selectively burn spectral holes linked to pairs with a given exchange coupling (Fig. 1D). From these resonant spectral changes, both the spin and optical properties of pair sites are therefore reconstructed. Importantly, since triplet pairs with different exchange interactions will have separated resonant fields, their associated spectra can be individually measured. Specific spin pairs with distinct spectral and spin properties can therefore be disentangled in an ensemble measurement and their local environment and microscopic properties probed. This is the key principle of our approach to provide a spin- and site-selective measurement of organic spin pairs.

TIPS-Tetracene.

Of the expanding class of singlet fission materials for photovoltaic application, solution-processable systems with a triplet energy close to the bandgap of silicon are particularly important since they could be integrated directly with established high-efficiency silicon technologies. One such material is TIPS-tetracene [5,12-Bis((triisopropylsilyl)ethynyl)-tetracene] (Fig. 2 A and B), a solution-processable derivative of the archetypal fission material tetracene (19, 20), which has been shown to undergo effective fission and generate exchange-coupled triplet pairs (13, 21, 22). Furthermore, singlet- and triplet-pair states are nearly iso-energetic in TIPS-tetracene, and so PL can be used to interrogate the fission products (21–23). Here we use TIPS-tetracene to study the spin and electronic structure of coupled triplet excitons. To achieve both high spectral and high field resolution, we perform measurements using both pulsed () and continuous wave (cw) () magnetic fields on three identically prepared samples (Materials and Methods): sample 1 under pulsed field at 1.4 K and samples 2 and 3 under cw fields at 2 K and 1.1 K, respectively. Samples are crystallites of approximately millimeter linear dimensions, containing multiple domains, prepared by evaporation from saturated solution, and were not specifically oriented with respect to the magnetic field. We first identify triplet-pair level crossings in TIPS-tetracene and then use these to spectrally characterize multiple distinct triplet pairs.

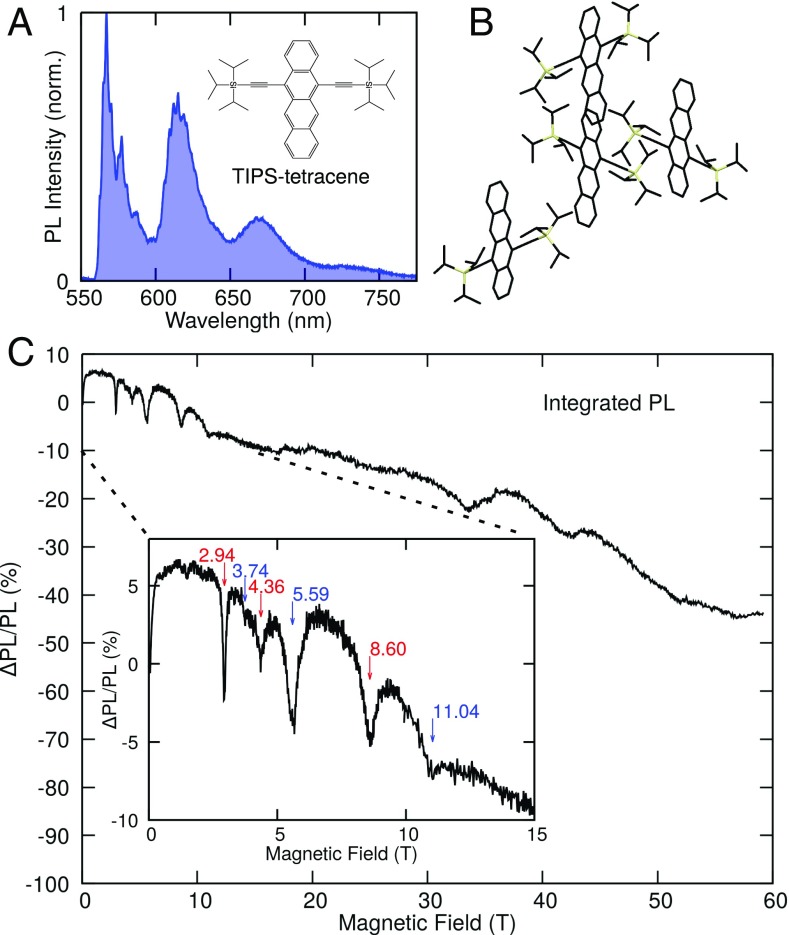

Fig. 2.

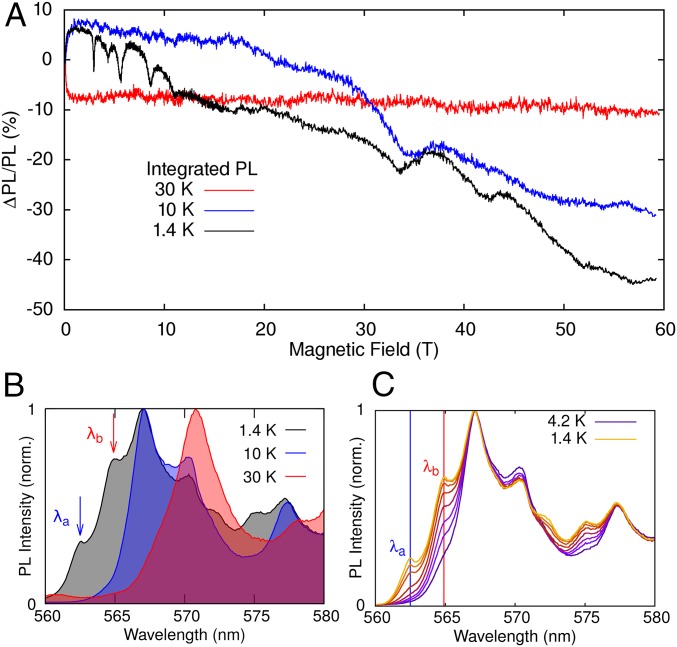

Level anticrossings of spin-1 pairs. (A) Chemical schematic and PL spectrum of TIPS-tetracene at 1.4 K (sample 1). (B) TIPS-tetracene unit cell displaying four inequivalent molecules. (C) Magneto-PL at 1.4 K integrated across all wavelengths showing a series of resonances (sample 1, pulsed fields).

Triplet-Pair Level Crossings.

Fig. 2C shows the changes in integrated PL up to 60 T for a TIPS-tetracene crystallite at (sample 1, pulsed fields; Materials and Methods), where PL/PL = [PL(B) PL(0)]/PL(0). Below , the conventional singlet fission magnetic-field effect is observed, indicative of weakly coupled triplet pairs (19), while at a very different behavior arises. On top of the monotonic PL reduction with field, which we discuss later, multiple PL resonances are apparent: a series below 15 T and additional resonances above 30 T, indicating triplet-pair level anticrossings. As shown in Fig. 1C, for a given triplet pair there are three possible resonances with the fission-generated singlet state, occurring with field ratios 1:3/2:3. The number of resonances in Fig. 2C therefore indicates multiple triplet pairs with different exchange interactions. While the resonances at can be separated into two progressions with 1:3/2:3 field ratios (red/blue labels, Fig. 2C) this does not clearly assign them or associate them with particular optical properties: We now show how the identified triplet-pair level crossings can be used to unambiguously decouple and spectrally characterize multiple interacting triplets in the same material.

Spectrally Resolving Interacting Triplets.

Fig. 3 B–D shows magneto-PL traces at three different wavelengths which correspond to high-energy regions of the TIPS-tetracene PL spectrum (Fig. 3A). In contrast to the integrated measurements, the magneto-PL at and shows a clear progression of three resonances following the 1:3/2:3 field ratios expected for level anticrossings with the singlet state (Fig. 3C, Inset), giving exchange interactions of 0.44 meV and 0.34 meV, respectively; i.e., , where is the exciton factor (13, 23) and the Bohr magneton. (Note that due to their spectral proximity, the 56-T resonance is also present in the trace.) In contrast to the spectral positions, at , resonances are present only at much higher fields of 33.4 T and . Since these do not occur at the expected 1:3/2 field ratios, we assign them to the lowest–field—i.e., singlet–triplet—anticrossings of distinct triplet pairs with exchange interactions of meV and , respectively (). This is further supported by their distinct temperature dependences which we describe later.

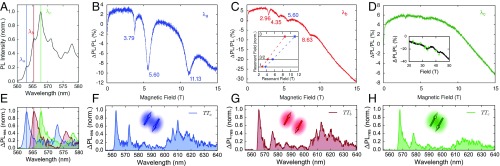

Fig. 3.

Magneto-optical spectroscopy of triplet pairs formed by singlet fission. (A) A 1.4 K PL spectrum with features at , , highlighted (sample 1). (B–D) Magneto-PL traces for the three spectral positions (sample 2). (B and C) Magnetic-field resonances at and corresponding to triplet pairs with exchange interactions of meV and (). (C, Inset) Resonant fields appear with ratios 1:3/2:3, as expected for the possible level crossings with the singlet state. Error bars are taken as 10% of the resonant linewidths. Dashed lines are guides to the eye. (D, Inset) Spectrally resolved PL measurements (marked field points) and integrated PL for reference (solid line) at . (E–H) Extracted spectra for the triplet pairs associated with the resonances (sample 1): overlaid (E) and shown individually (F–H).

As outlined in Fig. 1D, since the PL resonances for triplet pairs with different exchange interactions are readily separable in field, we can determine their emission characteristics from the spectral components that are diminished at each resonant field position, i.e., the difference in PL () when off resonance vs. on resonance: . [We note that for an accurate off-resonance subtraction in the presence of more slowly changing nonresonant field effects, we take as the average of the spectra either side of the resonance.] The spectra associated with each set of resonances (i.e., triplet pairs) are shown in Fig. 3 E–H and we label the associated triplet pairs . The resulting PL spectra show similar vibronic progressions, yet shifted peak emission energies with peaks centered at (Fig. 3E). The fact that the three spectra exhibit near-identical vibrational progressions but with an overall shift relative to each other shows that the states differ predominantly in their electronic rather than vibrational coupling. The relative shift indicates a difference in the local environment between the triplet pairs which results in distinct electronic interactions with the surrounding molecules. The question arises as to why a single material supports multiple triplet-pair sites with distinguishable electronic and spin energy levels. A natural explanation is the different molecular configurations accessible in TIPS-tetracene in which there are four rotationally inequivalent molecules in the crystal unit cell (Fig. 2B) (24). Multiple triplet pairs may therefore be supported and due to their differing interaction strengths and electronic environments be associated with different exchange couplings and optical emission spectra. (We note that as an alternative approach to species extraction, we find that independent spectral decomposition algorithms show good agreement with the spectra/lineshapes in Fig. 3; SI Appendix, IV. Numerical Spectral Decomposition.)

Vibrational Structure in Spectra.

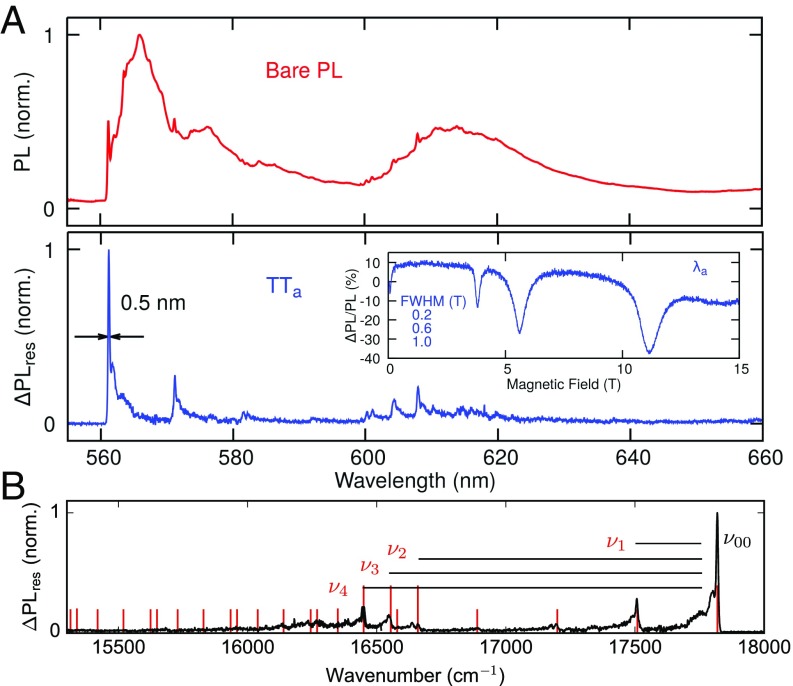

In keeping with previous assignments, the first spectral peaks at are attributed to 0–0, i.e., zero-phonon, transitions (22). This is also consistent with the greater overlap of low-energy modes on the higher-order vibrational transitions described in detail below (Fig. 4B). Sample 3 (measured at the lowest temperature) exhibited pronounced signatures (Fig. 4A), with linewidths of the extracted spectra reaching as low as 0.5 nm (), significantly narrower than the -nm linewidth of the 0–0 peak in the steady-state PL spectrum. This allows us to identify the vibronic transitions shown in Fig. 3 with greater accuracy (Fig. 4B). (Note that sample 2 spectra—Fig. 3 F–H—were measured using a spectrometer with lower spectral resolution, limiting the minimum linewidths.) We use this spectrum to extract four ground-state vibrational modes involved in the emission process. Fig. 4B shows a stick spectrum of the progression of one lower-energy mode with wavenumber and three higher-energy modes ( , , and ), showing good agreement with the measured spectra. These frequencies are in agreement with modes found in the ground-state Raman of TIPS-Tetracene films (22) with similar to typical C-C-C out-of-plane bending modes and similar to typical C-C stretching/C-C-H bending modes (25).

Fig. 4.

Vibrational structure in subnanometer resonant PL. (A) Zero-field PL spectrum, spectrum extracted from the 5.6-T resonance, and PL resonances for sample 3. (B) Resonant PL spectrum of with idealized vibrational progression (red lines) consisting of the 0–0 transition (); a dominant low-energy mode with wavenumber ; and three higher-energy modes = 1,160 cm1, cm1, and .

To our knowledge these are unique measurements of narrow optical spectra which can be associated with triplet pairs. The subnanometer optical linewidths obtained here are comparable to those obtained in fluorescence line-narrowing experiments of tetracene (26), highlighting the sensitivity of this approach. In contrast to all-optical measurements, the spin sensitivity afforded here allows clear assignment to triplet pairs. In addition, we note that spectral extraction of triplet-pair signatures does not require clearly visible peaks in the bare PL spectrum. For example, the longer-wavelength peaks associated with are unclear in the bare PL, and spectral decomposition of signatures is possible even in a sample with barely visible peaks (SI Appendix, IV. Numerical Spectral Decomposition).

Temperature-Dependent Signatures.

The identified triplet-pair species are further distinguishable through their temperature dependences. Fig. 5A shows the temperature dependence of the resonances in the integrated PL and the corresponding evolution of the emission spectrum. By 10 K, the resonances below 15 T are lost, concurrent with the loss of the and spectral features (Fig. 5B). The fact that the resonances at 33 T and 42 T have distinct temperature dependences supports their assignment to the first crossing of different triplet pairs [rather than a single species with a more structured exchange interaction (27)]. By 30 K, no PL resonances are observed, with no magnetic-field effect beyond T. Measurement of PL spectra between 4.2 K and 1.4 K (Fig. 5C) shows that the spectral features evolve significantly over this temperature range, indicating that escape from the associated emission sites has an activation temperature on the order of a few kelvins (). Interestingly, this is approximately the exchange coupling for . However, we note that this energy scale may alternatively be (i) a reorganization energy due to molecular reconfiguration or (ii) an electronic barrier between different excited states.

Fig. 5.

Temperature dependence of triplet-pair signatures. (A and B) Temperature-dependent integrated PL traces and spectra (sample 1). (C) Low-temperature behavior of the and spectral features which correspond to the triplet pairs with T and 2.96 T, respectively (sample 1).

High-Field Spin Mixing.

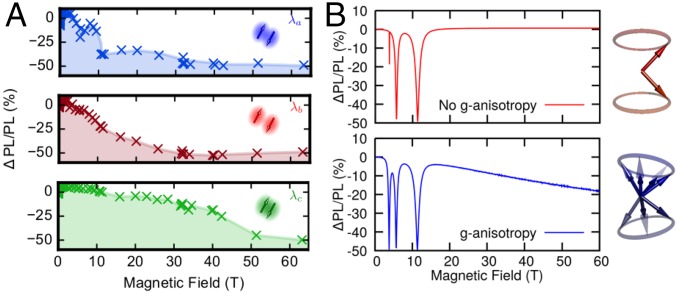

While resonant spectral analysis provides a window into the electronic structure associated with triplet pairs, the magnetic lineshapes provide insight into spin-mixing mechanisms and the emissive species. The magneto-PL shows a monotonic decrease with field, up to nearly 50% at 60 T (Fig. 2C), a drastically higher field than the -T scale usually seen in organic systems. This unanticipated high-field effect can be explained due to -factor anisotropy which can nonresonantly mix the singlet and triplet state , when triplets are orientationally inequivalent, analogous to effects observed in spin-1/2 pairs due to differences in isotropic values (4, 28, 29). The competition between spin-mixing Hamiltonian terms and total-spin–conserving exchange terms sets a characteristic saturation field for the effect , where is the relevant effective -factor difference (SI Appendix, VII. Spin Mixings). Triplet pairs with a larger exchange interaction should therefore have a larger characteristic field scale for this effect and hence also be distinguishable through their nonresonant spin mixing. Fig. 6C shows PL/PL for the three different spectral regions up to . The traces, which correspond to triplet pairs with similar exchange interactions (0.44 meV and ), show a similar nonresonant lineshape which saturates around 30 T, while the trace, associated with an order of magnitude larger exchange interaction, shows a much higher characteristic field scale for PL reduction, consistent with this mechanism. We note that high-field effects have rarely been observed in organic materials in general, and our observations show the relevance of spin-orbit coupling (responsible for anisotropy), which is usually assumed to be negligible.

Fig. 6.

Triplet-pair spin mixing. (A) Spectrally resolved high-field effect (sample 1) showing at spectral positions . (B) Simulation of the role of anisotropy. Inclusion of an anisotropic factor enhances the singlet-triplet level crossing (at field ) and produces a monotonic reduction in PL with field.

Singlet–Triplet Level Crossings.

A difference in matrices also provides a mixing mechanism for the singlet–triplet crossings. Since the pure triplet-pair states are antisymmetric with respect to particle exchange, while the states are symmetric (19), different mixing mechanisms are required for singlet–triplet vs. singlet–quintet hybridization. Singlet–quintet mixing can be mediated by the intratriplet zero-field splitting interaction (18) which characterizes the dipolar interaction between electron and hole and has strength in TIPS-tetracene (13, 23, 24, 30). However, to first order this coupling leaves the singlet–triplet crossing forbidden (SI Appendix, VII. Spin Mixings). Clear singlet–triplet crossings seen for therefore indicate an additional mixing mechanism. As with the high-field effect, this can be provided by a Hamiltonian term which mixes singlet and triplets to first order (Fig. 6B and SI Appendix, VII. Spin Mixings) with strength for an expected (31). Additionally, this crossing can be mediated by hyperfine interactions, with typical strengths of approximately milliteslas in organic semiconductors (32, 33).

The Role of Kinetics in Magnetic-Field Effect.

Interestingly, the magnetic linewidths of the PL resonances (Fig. 4A) are larger than expected based purely on the mixing matrix elements for the crossings, which would give linewidths of . We obtained similar linewidths in a single crystal sample (SI Appendix, V. Magneto-PL of TIPS-Tetracene Single Crystal), and therefore a distribution in can be ruled out as the dominant line-broadening mechanism. Instead, as detailed in SI Appendix, VIII. Kinetic Modelling, this indicates the broadening is predominantly due to the kinetics of the fission/fusion process.

For both resonant and nonresonant PL reductions, mixing is predominantly between the singlet and one other (triplet or quintet) pair state, and this sets a maximum PL/PL of (neglecting annihilation to a single triplet). This maximum is based on the distribution of the character across one state at zero field vs. two states at resonant positions/high field (18). The fact that the PL can be reduced by nearly 50% by a magnetic field (Figs. 2C and 4A) therefore indicates that strongly coupled triplet pairs can dominate the steady-state emission properties of singlet-fission systems. For identifying singlet fission, the observation that exchange-coupled triplets can dominate steady-state magnetic field effects is highly significant. Often, a low-field effect () characteristic of weakly coupled triplets (19) is taken to be a signature of the fission process (6). In contrast, our results show that singlet-fission magnetic-field effects can be drastically different between strongly and weakly coupled triplets and that high-field effects () can instead dominate.

We note that for fission-generated triplet pairs the emissive species may be either a distinct singlet exciton or, as proposed recently (22, 34), the triplet pairs themselves. While typically challenging to distinguish these scenarios, the combination of kinetically broadened linewidths and near 50% resonant PL reductions naturally arises only when triplet pairs emit via a separate singlet state, rather than directly themselves, showing the additional utility of these measurements in distinguishing these kinetic scenarios (SI Appendix, VIII. Kinetic Modelling).

Outlook.

The magneto-optic resolution of organic triplet pairs opens up the possibility to correlate their exchange and electronic structure with their chemical environment and physical conformation. Since the mixing matrix elements relevant for the PL resonances depend on the relative orientation between the external field and the triplet pair (18), measuring orientationally dependent PL resonances should allow triplet pairs to be assigned to specific molecular configurations. Identification of unambiguous spectral signatures of triplet pairs further means that these states can now be studied through purely optical means. For example, triplet-pair microscopy could be used to obtain information on the spatial distribution of pair sites across microcrystalline domains and map their diffusion (35–37), and resonant excitation could be used to address specific triplet pairs through site-specific fluorescence (38, 39).

While here we spectrally resolve triplet pairs in a singlet-fission material, these results are applicable to a range of other organic spin-pair systems. For example, triplet–triplet encounters are pivotal in photovoltaic upconversion systems (40) and organic light-emitting diodes (9, 41), and triplet-pair level anticrossings should also be observable in photovoltaic device architectures, where resonances could be measured through solar-cell photocurrent or quantum-dot emission (11). In spin-1/2 pairs, analogous spectrally resolved level crossings should help to clarify the spin and electronic structure of the emissive species central to thermally activated delayed fluorescence in next-generation organic light-emitting diode materials, and extracting optical signatures from level crossings observed in synthetic and biological radical pairs should provide further insights into these key intermediates (4, 33, 42, 43). Finally, the nanoscale sensitivity of exchange-coupled spins opens up the possibility to deliberately engineer them as joint spin-optical probes of complex molecular systems.

Materials and Methods

Samples were excited by 532-nm, 514-nm, or 485-nm laser illumination (similar results were obtained across this wavelength range). A long-pass filter was used to remove the laser line, and the collected PL was sent either to an avalanche photodiode for the integrated measurements or through a monochromator to a nitrogen-cooled CCD for the spectrally resolved measurements. Three different TIPS-tetracene crystallites prepared by evaporation from saturated solution were used, which we refer to as samples 1–3. X-ray diffraction confirmed that all samples indexed to the same unit cell previously determined for TIPS-tetracene (CCDC database, dx.doi.org/10.5517/cc119qsv), demonstrating that they had the same underlying solid-state structure. Integrated and spectrally resolved experiments to 68 T were performed using sample 1 under pulsed magnetic field at Laboratoire national des champs magnétiques intenses Toulouse. Spectrally resolved measurements up to 33 T were performed using samples 2 and 3 under steady-state fields at the High Field Magnet Laboratory, Nijmegen. For low-temperature measurements samples were either immersed in liquid helium (samples 1 and 3) or cooled via exchange gas with a surrounding helium bath (sample 2), giving base temperatures of K, and K for samples 1–3, respectively. PL spectra in Fig. 5C were taken with sample 1 in helium under continuous pumping. Further details and comparison of the samples are contained in SI Appendix, I. Samples, II. PL and Spectra in Samples 1–3, and III. Extraction of . The data underlying this paper are available at https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.22102.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by HFML-RU/FOM and LNCMI-CNRS, members of the European Magnetic Field Laboratory (EMFL), and by EPSRC (United Kingdom) via its membership in the EMFL (Grants EP/N01085X/1 and NS/A000060/1) and through Grant EP/M005143/1. L.R.W. acknowledges support from the Gates-Cambridge and Winton Scholarships. We acknowledge support from Labex ANR-10-LABX-0039-PALM, ANR SPINEX, and DFG SPP-1601 (Bi-464/10-2).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The numerical data underlying each figure in this paper have been deposited with the University of Cambridge Apollo depository, www.repository.cam.ac.uk, and may be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.22102.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1718868115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Petta JR, et al. Coherent manipulation of coupled electron spins in semiconductor quantum dots. Science. 2005;309:2180–2184. doi: 10.1126/science.1116955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lubitz W, Lendzian F, Bittl R. Radicals, radical pairs and triplet states in photosynthesis. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:313–320. doi: 10.1021/ar000084g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke TM, Durrant JR. Charge photogeneration in organic solar cells. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6736–6767. doi: 10.1021/cr900271s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steiner U, Ulrich T. Magnetic field effects in chemical kinetics and related phenomena. Chem Rev. 1989;89:51–147. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCamey D, et al. Spin rabi flopping in the photocurrent of a polymer light-emitting diode. Nat Mat. 2008;7:723–728. doi: 10.1038/nmat2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Congreve DN, et al. External quantum efficiency above 100% in a singlet-exciton-fission-based organic photovoltaic cell. Science. 2013;340:334–337. doi: 10.1126/science.1232994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mezyk J, Tubino R, Monguzzi A, Mech A, Meinardi F. Effect of an external magnetic field on the up-conversion photoluminescence of organic films: The role of disorder in triplet-triplet annihilation. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102:087404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.087404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu R, Zhang Y, Lei Y, Chen P, Xiong Z. Magnetic field dependent triplet-triplet annihilation in Alq3-based organic light emitting diodes at different temperatures. J Appl Phys. 2009;105:093719. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Eersel H, Bobbert P, Coehoorn R. Kinetic Monte Carlo study of triplet-triplet annihilation in organic phosphorescent emitters. J Appl Phys. 2015;117:115502. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith MB, Michl J. Singlet fission. Chem Rev. 2010;110:6891–6936. doi: 10.1021/cr1002613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson NJ, et al. Energy harvesting of non-emissive triplet excitons in tetracene by emissive PbS nanocrystals. Nat Mater. 2014;13:1039–1043. doi: 10.1038/nmat4097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabachnyk M, et al. Resonant energy transfer of triplet excitons from pentacene to PbSe nanocrystals. Nat Mater. 2014;13:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nmat4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss LR, et al. Strongly exchange-coupled triplet pairs in an organic semiconductor. Nat Phys. 2017;13:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tayebjee MJ, et al. Quintet multiexciton dynamics in singlet fission. Nat Phys. 2017;13:182–188. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Basel BS, et al. Unified model for singlet fission within a non-conjugated covalent pentacene dimer. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15171. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakasa M, et al. What can be learned from magnetic field effects on singlet fission: Role of exchange interaction in excited triplet pairs. J Phys Chem C. 2015;119:25840–25844. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yago T, Ishikawa K, Katoh R, Wakasa M. Magnetic field effects on triplet pair generated by singlet fission in an organic crystal: Application of radical pair model to triplet pair. J Phys Chem C. 2016;120:27858–27870. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayliss SL, et al. Spin signatures of exchange-coupled triplet pairs formed by singlet fission. Phys Rev B. 2016;94:045204. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merrifield RE. Magnetic effects on triplet exciton interactions. Pure Appl Chem. 1971;27:481–498. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burdett JJ, Piland GB, Bardeen CJ. Magnetic field effects and the role of spin states in singlet fission. Chem Phys Lett. 2013;585:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern HL, et al. Identification of a triplet pair intermediate in singlet exciton fission in solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:7656–7661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503471112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stern HL, et al. Ultrafast triplet pair formation and subsequent thermally activated dissociation control efficient endothermic singlet exciton fission. Nat Chem. 2017;9:1205–1212. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayliss SL, et al. Geminate and nongeminate recombination of triplet excitons formed by singlet fission. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;112:238701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.238701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayliss SL, et al. Localization length scales of triplet excitons in singlet fission materials. Phys Rev B. 2015;92:115432. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alajtal A, Edwards H, Elbagerma M, Scowen I. The effect of laser wavelength on the Raman spectra of phenanthrene, chrysene, and tetracene: Implications for extra-terrestrial detection of polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2010;76:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofstraat J, Schenkeveld A, Engelsma M, Gooijer C, Velthorst N. Temperature effects on fluorescence line narrowing spectra of tetracene in amorphous solid solutions. Analytical implications. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc A. 1989;45:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kollmar C, Sixl H, Benk H, Denner V, Mahler G. Theory of two coupled triplet states-electrostatic energy splittings. Chem Phys Lett. 1982;87:266–270. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devir-Wolfman AH, et al. Short-lived charge-transfer excitons in organic photovoltaic cells studied by high-field magneto-photocurrent. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4529. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Sahin-Tiras K, Harmon NJ, Wohlgenannt M, Flatté ME. Immense magnetic response of exciplex light emission due to correlated spin-charge dynamics. Phys Rev X. 2016;6:011011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weil JA, Bolton JR. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Wiley; New York: 2007. pp. 162–187. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schott S, et al. Tuning the effective spin-orbit coupling in molecular semiconductors. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15200. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCamey D, et al. Hyperfine-field-mediated spin beating in electrostatically bound charge carrier pairs. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104:017601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.017601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zarea M, Carmieli R, Ratner MA, Wasielewski MR. Spin dynamics of radical pairs with restricted geometries and strong exchange coupling: The role of hyperfine coupling. J Phys Chem A. 2014;118:4249–4255. doi: 10.1021/jp5039283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yong CK, et al. The entangled triplet pair state in acene and heteroacene materials. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15953. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irkhin P, Biaggio I. Direct imaging of anisotropic exciton diffusion and triplet diffusion length in rubrene single crystals. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107:017402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.017402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akselrod GM, et al. Visualization of exciton transport in ordered and disordered molecular solids. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3646. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan Y, et al. Cooperative singlet and triplet exciton transport in tetracene crystals visualized by ultrafast microscopy. Nat Chem. 2015;7:785–792. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bässler H, Schweitzer B. Site-selective fluorescence spectroscopy of conjugated polymers and oligomers. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:173–182. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orrit M, Bernard J, Personov R. High-resolution spectroscopy of organic molecules in solids: From fluorescence line narrowing and hole burning to single molecule spectroscopy. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:10256–10268. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh-Rachford TN, Castellano FN. Photon upconversion based on sensitized triplet-triplet annihilation. Coord Chem Rev. 2010;254:2560–2573. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldo MA, Adachi C, Forrest SR. Transient analysis of organic electrophosphorescence. II. Transient analysis of triplet-triplet annihilation. Phys Rev B. 2000;62:10967–10977. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss EA, Ratner MA, Wasielewski MR. Direct measurement of singlet- triplet splitting within rodlike photogenerated radical ion pairs using magnetic field effects: Estimation of the electronic coupling for charge recombination. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:3639–3647. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hiscock HG, et al. The quantum needle of the avian magnetic compass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4634–4639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600341113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.