Significance

Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots of great ecological, economic, and aesthetic importance. Their global decline due to climate change and other anthropogenic stressors has increased the urgency to understand the molecular bases of various aspects of coral biology, including the interactions with algal symbionts and responses to stress. Recent genomic and transcriptomic studies have yielded many hypotheses about genes that may be important in such processes, but rigorous testing of these hypotheses will require the generation of mutations affecting these genes. Here, we demonstrate the efficient production of mutations in three target genes using the recently developed CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technique. By clarifying aspects of basic coral biology, such genetic approaches should also provide a more solid foundation for coral-conservation efforts.

Keywords: Acropora millepora, coral, CRISPR/Cas9, genome editing

Abstract

Reef-building corals are critically important species that are threatened by anthropogenic stresses including climate change. In attempts to understand corals’ responses to stress and other aspects of their biology, numerous genomic and transcriptomic studies have been performed, generating a variety of hypotheses about the roles of particular genes and molecular pathways. However, it has not generally been possible to test these hypotheses rigorously because of the lack of genetic tools for corals. Here, we demonstrate efficient genome editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in the coral Acropora millepora. We targeted the genes encoding fibroblast growth factor 1a (FGF1a), green fluorescent protein (GFP), and red fluorescent protein (RFP). After microinjecting CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes into fertilized eggs, we detected induced mutations in the targeted genes using changes in restriction-fragment length, Sanger sequencing, and high-throughput Illumina sequencing. We observed mutations in ∼50% of individuals screened, and the proportions of wild-type and various mutant gene copies in these individuals indicated that mutation induction continued for at least several cell cycles after injection. Although multiple paralogous genes encoding green fluorescent proteins are present in A. millepora, appropriate design of the guide RNA allowed us to induce mutations simultaneously in more than one paralog. Because A. millepora larvae can be induced to settle and begin colony formation in the laboratory, CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing should allow rigorous tests of gene function in both larval and adult corals.

Reef-building corals are ecologically, economically, and aesthetically important species that provide critical habitat, primary production, and biodiversity in the oceans (1, 2). The ability of corals to grow in nutrient-poor waters and to deposit calcium carbonate-based reef materials depends on their symbiosis with photosynthetic dinoflagellate algae in the genus Symbiodinium, which supply most of the necessary energy (3–5). Corals are currently under threat worldwide due to anthropogenic environmental stresses including those related to climate change (2, 6), many of which lead to a breakdown in the critical symbiosis (called “coral bleaching” because of the loss of the algal pigments). These global declines have heightened the need for a deeper understanding of coral biology, leading to a recent surge in research that has included numerous genomic and transcriptomic studies (e.g., refs. 7–16). In particular, studies of gene expression in corals and other cnidarians have suggested many plausible hypotheses about the genes and molecular pathways controlling fundamental processes such as partner selection during symbiosis establishment, metabolic exchange between the symbiotic partners, biomineralization, local adaptation and physiological plasticity, and the response to stress. However, the evidence in support of such hypotheses has remained largely correlational because of a lack of genetic tools that would allow more rigorous testing.

Reverse-genetic methods producing knockout or knockdown of genes of interest have successfully elucidated gene function in many model and nonmodel organisms. Recently, the range and power of such methods has been dramatically expanded by the emergence of the CRISPR/Cas9 genome-editing technology, which can be applied to diverse organisms and has facilitated not only the generation of loss-of-function mutations but also the introduction of more subtly modified genes, the tagging of proteins, and large-scale genomic restructuring (17–19). In cnidarians, this tool has been used in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis and the hydrozoan Hydractinia echinata by microinjecting single-guide RNA (sgRNA)/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes into one-cell zygotes (20–22), a powerful method for producing genetic changes at an early developmental stage (19, 23, 24). An obstacle to applying this technique to corals is the limited availability of gametes to generate zygotes. Most reef-building corals reproduce seasonally through broadcast spawning, releasing gametes once or a few times a year in response to temperature and lunar cues (25–27). Nonetheless, for many coral species, there are well-established methods for obtaining gametes, achieving fertilization, culturing larvae in the laboratory, and inducing larval settlement and metamorphosis (26, 28). These methods make it feasible both to microinject one-cell zygotes with genome-modification reagents and to analyze the resulting phenotypes despite the undoubted logistical challenges.

In an initial attempt to generate loss-of-function mutations using CRISPR/Cas9 in corals, we targeted the Acropora millepora genes encoding fibroblast growth factor 1a (FGF1a), green fluorescent protein (GFP), and red fluorescent protein (RFP). FGF1a appears to be single copy in the genome and encodes an extracellular FGF-signaling ligand; it was chosen because experiments in both Nematostella and A. millepora have suggested that FGF signaling plays a role in sensing the environment and/or in modulating gene expression during larval settlement and metamorphosis (29–31). Both GFP and RFP genes are multicopy in this species; they are highly expressed in larvae and responsive to environmental perturbations (32–37). The visual conspicuousness of GFP and RFP proteins in larvae and their putative ecological importance made these genes promising candidates for such tests despite their multiple copies, particularly as the high nucleotide-sequence similarity of these copies appeared likely to allow the targeting of multiple paralogs with one sgRNA.

To our knowledge, the only report to date of successful gene-knockout or gene-knockdown experiments in corals is one in which a morpholino was used to perform transient loss-of-function experiments in larvae of Acropora digitifera (38). We report here the efficient induction of mutations in each of the three targeted A. millepora genes after microinjection of appropriate sgRNA/Cas9 complexes, showing the potential of CRISPR/Cas9 to allow reverse-genetic approaches in corals.

Results

Design and in Vitro Testing of sgRNAs.

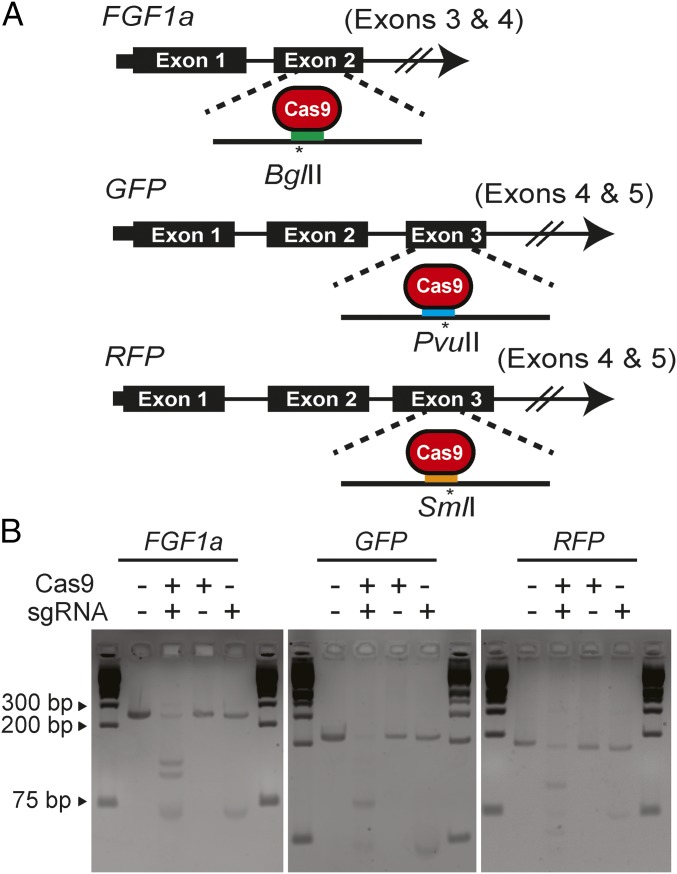

To explore the use of CRISPR/Cas9 to generate mutations in corals, we designed sgRNAs targeting the A. millepora FGF1a, GFP, and RFP genes (Introduction). The sgRNAs were designed to minimize the chances of off-target effects and to encompass endogenous restriction sites that would facilitate the detection of mutations (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). We also targeted positions that should be far enough upstream within the genes’ coding sequences that mutations altering the reading frame would knock out gene function but also far enough downstream that it seemed unlikely that functional gene products could be generated by the use of an alternative transcription start site downstream of the induced mutation (Fig. 1A). In vitro tests showed that some of the sgRNAs could effectively guide cutting by Cas9 of PCR-amplified fragments of genomic DNA, whereas no cleavage was observed when the DNA fragments were incubated with either Cas9 or the sgRNA alone (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Design and activity in vitro of sgRNAs targeting A. millepora genes. (A) sgRNAs targeting exon 2 (of at least four) of FGF1a, exon 3 (of five) of GFP genes, and exon 3 (of five) of RFP genes were designed to induce double-strand breaks near endogenous restriction-enzyme sites that could be used to detect induced mutations. Colored bars, approximate locations of the sgRNA-binding sites; asterisks, predicted Cas9 cleavage sites and the nearby restriction sites. (B) Digestion in vitro of FGF1a, GFP, or RFP target DNA (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods) incubated with Cas9 protein, the appropriate sgRNA (as transcribed in vitro from the pDR274-based construct), or both. Fragments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis; outside lanes of each gel show molecular-size markers.

Induction of Mutations After Microinjection of Larvae.

To avoid the possible toxicity and/or temporal delay in mutation induction that can be seen when vector-driven expression of sgRNA and Cas9 is used (39), we injected in vitro transcribed sgRNAs that had been precomplexed with Cas9 protein (20, 21, 40–42). On each of two nights of spawning, >400 freshly fertilized zygotes (Materials and Methods) were injected either with a set of two or three sgRNA/Cas9 complexes (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods) or with Cas9 protein alone as a negative control (Table 1). Survival and continued development of the embryos into larvae was seen in ∼50–75% of the injected individuals (Table 1).

Table 1.

Numbers of injected and surviving A. millepora zygotes

| Night 1 | Night 2 | ||||

| Target gene(s)* | FGF1a | GFP | RFP | FGF1a | None (Cas9-only) |

| No. of individuals injected successfully† | 146 | 123 | 147 | 246 | 227 |

| No. of individuals surviving until 12 h postfertilization‡ | 74 | 88 | 79 | 116 | 176 |

| Percent of individuals surviving until 12 h postfertilization, %‡ | 51 | 72 | 54 | 47 | 78 |

For each gene, a mixture of sgRNA/Cas9 complexes was injected (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods); there were two such complexes for FGF1a, three for GFP, and two for RFP.

As judged by the phenol-red injection marker (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

As judged by the numbers of larvae that were seemingly intact at the time of observation.

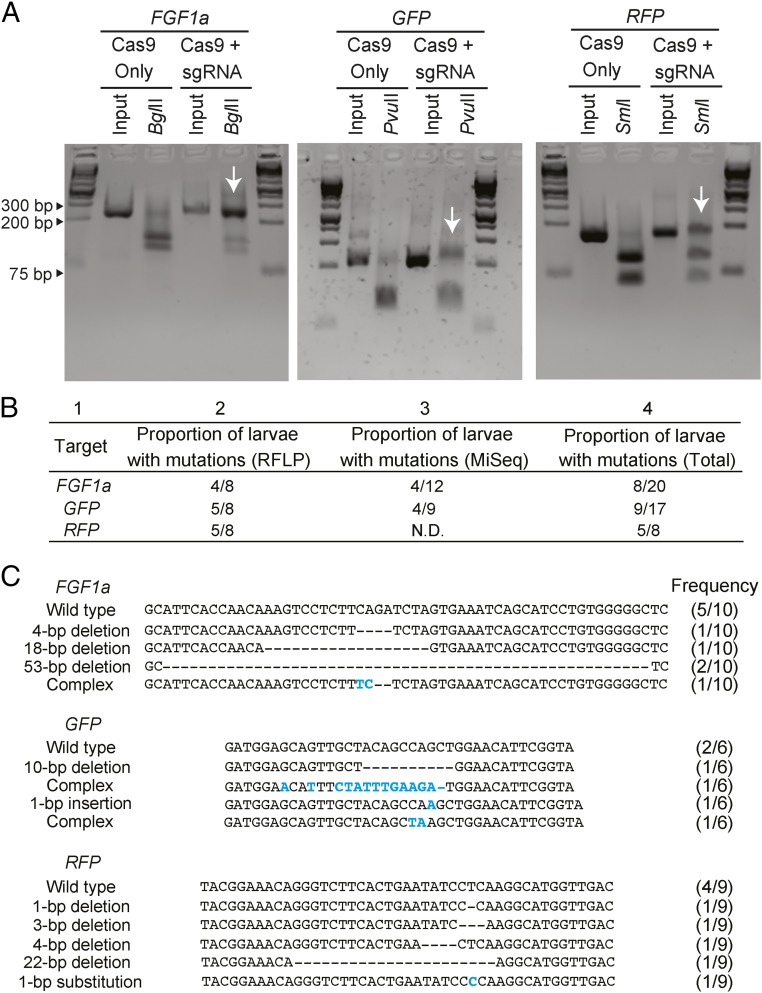

We used several methods to assess mutation induction in the surviving larvae. First, we used the restriction-fragment-length-polymorphism (RFLP) assays allowed by the restriction sites in the sgRNA-binding sites to estimate the fractions of larvae carrying mutations. For each gene, some injected larvae displayed incomplete digestion with the relevant restriction enzyme (Fig. 2A, arrows), indicating that at least some copies of the gene in those larvae had lost the restriction site because of induced mutations. These assays suggested that mutations had been induced in roughly half the larvae that appeared to have been successfully injected (Fig. 2B, column 2). Second, to determine the types of mutations induced, we cloned and sequenced PCR-amplified fragments from one larva for each target gene that had been found to harbor mutations by the RFLP assay. In each case, we found both wild-type sequences and multiple, distinct mutant alleles in the larvae examined (Fig. 2C); the mutations were of the types expected from studies of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in other systems (40, 42–47). The variety of mutations observed indicates that mutagenesis could occur during at least the first few cell cycles after injection of the embryos.

Fig. 2.

Efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in injected A. millepora embryos. (A) Genomic DNA from individual larvae that had been injected with Cas9 protein alone or with the sgRNA/Cas9 protein complexes for one of the target genes was amplified by PCR, digested with the appropriate restriction enzyme, and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Each pair of interior lanes represents one larva; the outside lanes show molecular-size markers. Arrows indicate the incompletely digested DNA. (B) Proportions of injected larvae with mutations as determined by restriction digestion (RFLP, as in A) or MiSeq amplicon sequencing (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). The total numbers of larvae tested by each method and the numbers found to be carrying mutations are indicated. N.D., not determined. Columns are numbered for ease of reference in the text. (C) Varieties of specific mutations in individual larvae. For each gene, genomic DNA was PCR-amplified and cloned from one injected larva that appeared from RFLP analysis (A and B) to harbor mutations, the indicated numbers of clones were Sanger-sequenced, and the sequences were aligned. Base-pair changes are shown in blue and deletions by dashes; the numbers of wild-type and variant sequences observed are indicated. Note that for GFP and RFP, the sequences shown could be from more than one paralog in each case (see text).

Third, to get an independent assessment of the fractions of larvae with induced mutations, we used high-throughput MiSeq amplicon sequencing of individual larvae that had been injected with either the FGF1a or the GFP sgRNA/Cas9 complex (see SI Appendix, Table S1 for sequencing statistics). Of the larvae sequenced, 4 of 12 FGF1a-injected individuals and 4 of 9 GFP-injected individuals contained mutations at the predicted target site (Fig. 2B, column 3), consistent with the results from the RFLP assays. The presence of mutations in roughly half of the successfully injected larvae (Fig. 2B, column 4) indicates a high efficiency of genomic editing, consistent with observations made in other organisms (18, 39, 42, 48–50).

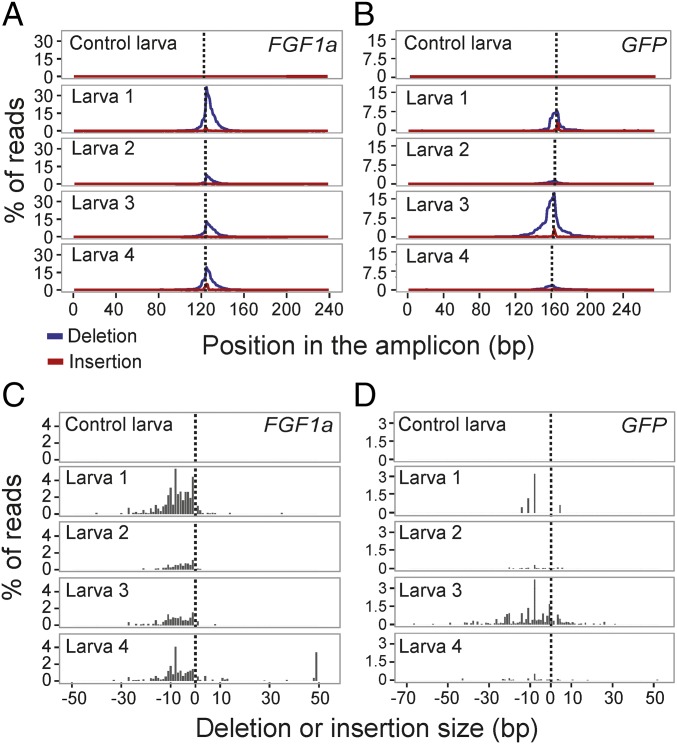

The MiSeq sequencing also allowed us to get additional quantitative assessments of the mutational spectra within individual larvae. Of the four FGF1a-injected larvae and four GFP-injected larvae that had been found to have mutations (Fig. 2B, column 3), averages of ∼22% (FGF1a) and ∼9% (GFP) of total reads showed at least one deleted and/or inserted base (Fig. 3 A and B). As expected, the mutations were concentrated around the predicted sites of the Cas9-induced double-strand breaks, and the majority were deletions of 1–10 bp (Fig. 3 C and D), typical of double-strand break repair by nonhomologous end joining (51). The spectra of deletion and insertion sizes varied among individuals (Fig. 3 C and D) and were similar to the patterns of CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations in other systems (43, 44).

Fig. 3.

Mutational spectra in CRISPR/Cas9-injected animals as determined by MiSeq amplicon sequencing. For each gene, one control larva (only Cas9 protein injected) and the four sgRNA/Cas9-injected larvae determined by MiSeq sequencing to contain mutations (Fig. 2B, column 3) were analyzed further. (A and B) The percentages of reads with a deleted (blue lines) or inserted (red lines) base at each nucleotide position. Dotted lines, expected Cas9 cut sites. Note that for GFP, the method of analysis used here does not resolve the paralogous copies of the gene (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). (C and D) The percentages of reads with deletions (Left of dotted line) or insertions (Right of dotted line) of various sizes in the same larvae as shown in A and B.

Genomic Modification of Two or More GFP Paralogs with One sgRNA.

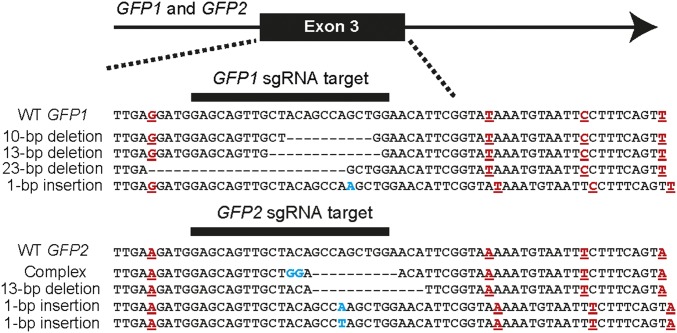

GFP and RFP are encoded by gene families with unknown numbers of copies in the A. millepora genome and sequences that are incompletely resolved in the available genome sequence (Introduction). Thus, it seemed possible that the CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutations described in Figs. 2 and 3 for these genes do not represent mutations at a single genetic locus but rather at two or more closely related paralogs. For GFP, the MiSeq amplicon sequencing allowed partial resolution of this issue. Single-nucleotide differences among the sequence reads from control individuals (injected with Cas9 alone) allowed most of the reads to be clustered into eight groups that presumably represent different paralogous and/or allelic sequences (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods, and Fig. S1). Comparison with the genome sequence showed that some of these sequences aligned best with contig c1015068 and some with contig c849821, and we named the genes on these contigs GFP1 and GFP2, respectively. An 83-bp intronic region at the 3′ end of the amplicon had sufficient sequence diversity to discriminate among the eight sequence groups (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), so we used this 83-bp region to sort the sequences obtained from the sgRNA/Cas9-injected individuals. This analysis indicated that mutations had been obtained in both GFP1 and GFP2 using the same sgRNA (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Editing of two GFP paralogs in a single larva with a single sgRNA. The sequences from larva 4 (Fig. 3B) were clustered into eight groups using the single-nucleotide differences within an 83-bp intronic region (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Shown are representative mutant alleles that fell into groups 1 and 6 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), which can be assigned with confidence to GFP1 and GFP2, respectively (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). Dashes, deleted nucleotides; blue lettering, inserted or altered nucleotides; red lettering, positions at which the GFP1 and GFP2 alleles in this larva differed within this 64-bp segment. (Note that only two of these positions are among those diagnostic for GFP1 vs. GFP2: cf. SI Appendix, Fig. S1.)

Attempts to Detect Phenotypes Associated with the CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Mutations.

FGF signaling is required for apical-tuft development and metamorphosis in Nematostella (29, 30). Although A. millepora larvae do not appear to have apical tufts (52), it remains likely that FGF signaling plays a role in controlling metamorphosis in this species (31). Thus, we exposed larvae to chips of crustose coralline algae (an inducer of settlement and metamorphosis) and examined them ∼20 h later (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods). In scoring 94 control larvae (injected with Cas9 alone) and 53 larvae that had been injected with the FGF1a sgRNA/Cas9 complexes, we detected no decrease in the percentage of larvae undergoing metamorphosis in the latter group relative to the former. If anything, the frequency of metamorphosis was slightly higher in the sgRNA/Cas9-injected animals, but it is not clear that this difference was biologically significant, and there was no practicable route to asking if the possible difference could be ascribed to induced mutations (Discussion).

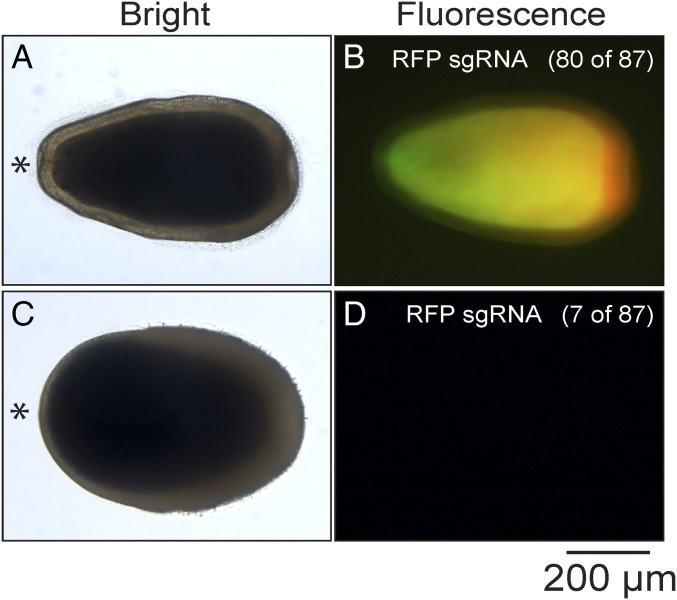

By 5 d of development, wild-type A. millepora larvae display GFP fluorescence throughout most of their gastroderm and RFP fluorescence in epidermal cells primarily at their aboral ends (53, 54). In 54 of 55 control animals (injected with Cas9 alone) and 50 of 50 animals injected with the GFP sgRNA/Cas9 complexes, we saw no obvious change in this fluorescence pattern. Similarly, 80 of 87 animals injected with the RFP sgRNA/Cas9 complexes also showed no obvious change in fluorescence pattern (Fig. 5 A and B). However, in seven animals, we observed neither GFP nor RFP fluorescence (Fig. 5 C and D and Discussion).

Fig. 5.

GFP (green) and RFP (red) fluorescence in larvae that had been injected with RFP sgRNA/Cas9 complexes. Larvae were observed at 5 d postfertilization; bright-field and merged GFP- and RFP-fluorescence images are shown for each larva. (A and B) Most injected larvae showed fluorescence patterns indistinguishable from those of wild type. (C and D) Some injected larvae showed neither GFP nor RFP fluorescence. Asterisk (*), oral end of larva. (Scale bar, 200 µm.)

Discussion

There is an urgent need to develop the genetic methods that will allow rigorous testing of hypotheses about gene and pathway function in various aspects of coral biology. The powerful CRISPR/Cas9 approach should greatly facilitate such efforts, and we report here encouraging results in this direction. In this study, we used A. millepora because of its ecological importance in the Indo-Pacific region, its ready availability at the Australian study site, the ability to obtain spawning in the laboratory at predictable times (25–27), the ability to get its aposymbiotic larvae to settle and undergo metamorphosis [thus allowing a wide range of phenotypes to be investigated (26, 28)], and the rapidly accumulating genomic and transcriptomic resources for it and its congeners (7, 8, 12, 15, 16, 55). However, the same approach should be broadly applicable to other broadcast-spawning corals for which it is possible to collect eggs and sperm for controlled fertilization. In this regard, recent advances in achieving spawning of several Acropora species after long-term aquarium culture (56) should considerably broaden access to larvae for such experiments. It is also critical that the available genomic sequences are sufficiently accurate and well annotated to allow effective identification of target genes and reliable sgRNA design, and such data are accumulating steadily for a variety of coral species (14, 15).

In this study, we used RFLP analysis, conventional Sanger sequencing, and high-throughput Illumina sequencing to demonstrate the generation of a variety of mutations after injection of A. millepora zygotes with preassembled sgRNA/Cas9 complexes. The mutations were of the types expected from studies of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in other organisms (18, 39, 42, 48–50), and most should disrupt gene function. Our results suggest several points to consider in designing future studies.

First, the strategy used here for sgRNA design facilitates initial evaluation of mutagenic efficiency and may be particularly useful if obtaining access to zygotes of the coral species of interest necessitates work at sites with limited laboratory facilities. Because we chose sgRNA-binding sites that overlap (or lie very close to) endogenous restriction-enzyme sites, preliminary assessment of the success of the desired genome modifications could be made rapidly by gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2A) in advance of more definitive analysis of mutations using DNA sequencing.

Second, all 11 mutant larvae that we sequenced harbored both wild-type and multiple different mutant alleles of the target genes (Figs. 2C and 3 A and B). These results indicate that the sgRNA/Cas9 complexes remained active for several cell cycles after initial injection but also that none of the animals analyzed had sustained biallelic mutations (mutations in the target gene on both copies of the chromosome) before first cleavage. (Because generation of a mutation destroys the sgRNA-binding site and thus the potential for further mutations, any animals that had sustained biallelic mutations before first cleavage would contain no wild-type copies of the gene and at most two distinct mutant alleles.) As there is little immediate prospect of raising mutagenized animals to adulthood and generating homozygous individuals by genetic crosses, obtaining animals that have sustained early biallelic mutations will be critical to the analysis of phenotypes of interest. Such animals have been recovered in CRISPR/Cas9 studies of other species (e.g., refs. 40, 47, and 48), and this should also be feasible in corals. Note that in the present study, due to an error in sgRNA design (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods), we injected only one-half or one-third of the intended amounts of active sgRNA/Cas9 complexes, yet we still observed high rates of induced mutations, and we sequenced only small numbers of larvae, so that we could easily have missed ones with early biallelic mutations. Indeed, some larvae that were examined using the RFLP assay, but not sequenced, appeared to show a complete (or nearly so) replacement of wild-type by mutant alleles (Fig. 2A, FGF1a, arrow). In addition, further technical developments (e.g., in the optimization of sgRNA design: chopchop.cbu.uib.no) should also improve the prospects for obtaining biallelic mutants. Finally, effective phenotypic analysis has also been achieved in other organisms in which the F0 animals (the injected generation) are mosaic (only some cells carry biallelic mutations) but the phenotypes of interest are cell-autonomous and easily observed (45, 48, 57), and this may also be possible in corals. Thus, as hundreds of coral zygotes can be injected in a single session, it should be possible to recover larvae with the genotypes needed for effective phenotypic analysis.

Third, in future studies, it will be important to choose the target genes judiciously to avoid the kinds of issues that hampered us in this study and maximize the chances of obtaining informative phenotypes. In the case of FGF1a, the role of the FGF pathway in signaling during embryogenesis and metamorphosis is likely to be complicated. For example, in Nematostella, there are at least two ligands, FGFa1 and FGFa2, with opposite effects on metamorphosis (29, 30), making it difficult to predict the phenotype that would result from mutations inactivating the A. millepora FGF gene that we targeted. Moreover, if the mutant phenotype is actually to increase the fraction of larvae undergoing metamorphosis to more than the ∼70% observed in wild type, it would be difficult to ascribe the metamorphosis of any individual larva to the influence of a mutation that it had sustained.

In the cases of GFP and RFP, the presence in A. millepora of multiple paralogs clearly militated against our chances of seeing phenotypes for these genes. Although we showed convincingly that the sgRNA used did produce mutations in at least two GFP paralogs, it remains unclear how many paralogs there are or whether all of their sequences are similar enough to be targeted by the same sgRNA. Even if so, it would have required a very high efficiency of mutation induction to have achieved biallelic mutations in all paralogs expressed in larvae. Moreover, the widespread expression of GFP in the larvae (Fig. 5 A and B) means that the biallelic mutations would have needed to be present early enough to affect all of the cells of this lineage (or lineages). The situation is similar for RFP, although the seemingly more restricted localization of RFP expression in the larvae (Fig. 5 A and B) might allow biallelic mutations affecting the relevant paralogs(s) to give a detectable phenotype even if they arose somewhat later in development. Indeed, it remains possible that the nonfluorescent larvae observed (Fig. 5 C and D) actually were expressing a mutant phenotype, although it remains unclear why they would have lacked GFP as well as RFP fluorescence. Unfortunately, no further analysis was possible because of the loss during shipment of the samples needed for molecular analysis of the possible mutations.

In summary, the methods and results reported here should provide a solid basis for future CRISPR/Cas9 studies of gene function in corals and other cnidarians. At least for the immediate future, such studies should probably focus on target genes that are single copy and likely to give phenotypes that are detectable even if not all cells in the larvae are biallelic mutants. The availability of effective reverse-genetic methods should allow genomic studies of corals and other cnidarians to move beyond hypotheses based on correlations to a rigorous analysis of the functions of specific genes and pathways.

Materials and Methods

Collection and Spawning of A. millepora.

In November 2016, gravid adult colonies of A. millepora were collected from Trunk Reef in the Central Great Barrier Reef (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority Permit G11/34671.1), transported to the National Sea Simulator at the Australian Institute for Marine Science, and placed in outdoor tanks under ambient temperature and light conditions to allow spawning. On November 18, six colonies spawned at ∼9:30 PM, and egg–sperm bundles from each individual were collected and broken up using gentle washing in 100 µm-mesh sieves, which retain the eggs while the sperm pass through. Sperm from the six individuals were pooled and diluted to a concentration of ∼106/mL, and the eggs were also pooled. Aliquots of sperm and eggs were mixed to allow fertilization at ∼10:00 PM and at intervals of ∼30 min thereafter; in each cycle, eggs and sperm were first incubated together at an ambient temperature of 27 °C for 15 min and then moved to a 24 °C room for microinjection. This staggered fertilization allowed time for microinjection of each batch of zygotes before first cleavage, which occurred 30–60 min after fertilization. On November 19, four other individuals spawned, and their eggs and sperm were collected and processed as on the preceding day.

Other Methods.

SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods, describes the generation and testing of sgRNAs, the method for microinjection, and the methods used for molecular analysis of mutations and assessment of possible phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Sanders, B. Mason, and B. Fu for helpful suggestions on the design of the sgRNAs; H. Elder and I. Bjørnsbo for valuable assistance during coral spawning; and Eppendorf South Pacific for loan of the microinjection system. MiSeq sequencing was performed by the Genomic Sequencing and Analysis Facility at the University of Texas at Austin. Some bioinformatic analyses were carried out using the computational resources of the Texas Advanced Computing Center. Funding for this study was provided by NSF Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant DEB-1501463 (to M.E.S. and M.V.M.); the Simons Foundation Grant LIFE 336932 (to J.R.P.); and internal Australian Institute for Marine Science funding (to L.K.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1722151115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Moberg F, Folke C. Ecological goods and services of coral reef ecosystems. Ecol Econ. 1999;29:215–233. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes TP, et al. Coral reefs in the Anthropocene. Nature. 2017;546:82–90. doi: 10.1038/nature22901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muscatine L, Cernichiari E. Assimilation of photosynthetic products of zooxanthellae by a reef coral. Biol Bull. 1969;137:506–523. doi: 10.2307/1540172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muscatine L, Falkowski PG, Porter JW, Dubinsky Z. Fate of photosynthetic fixed carbon in light- and shade-adapted colonies of the symbiotic coral Stylophora pistillata. Proc R Soc B. 1984;222:181–202. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davy SK, Allemand D, Weis VM. Cell biology of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:229–261. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05014-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes TP, et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature. 2017;543:373–377. doi: 10.1038/nature21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shinzato C, et al. Using the Acropora digitifera genome to understand coral responses to environmental change. Nature. 2011;476:320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moya A, et al. Whole transcriptome analysis of the coral Acropora millepora reveals complex responses to CO2-driven acidification during the initiation of calcification. Mol Ecol. 2012;21:2440–2454. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lehnert EM, et al. Extensive differences in gene expression between symbiotic and aposymbiotic cnidarians. G3 (Bethesda) 2014;4:277–295. doi: 10.1534/g3.113.009084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgarten S, et al. The genome of Aiptasia, a sea anemone model for coral symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:11893–11898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513318112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon GB, et al. Genomic determinants of coral heat tolerance across latitudes. Science. 2015;348:1460–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1261224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barshis DJ. Genomic potential for coral survival of climate change. In: Birkeland C, editor. Coral Reefs in the Anthropocene. Springer; Heidelberg, Germany: 2015. pp. 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenkel C, Matz MV. Enhanced gene expression plasticity as a mechanism of adaptation to a variable environment in a reef-building coral. Nat Ecol Evol. 2016;1:59667. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharya D, et al. Comparative genomics explains the evolutionary success of reef-forming corals. eLife. 2016;5:e13288. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liew YJ, Aranda M, Voolstra CR. Reefgenomics.Org: A repository for marine genomics data. Database (Oxford) 2016;2016:baw152. doi: 10.1093/database/baw152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traylor-Knowles N, Rose NH, Sheets EA, Palumbi SR. Early transcriptional responses during heat stress in the coral Acropora hyacinthus. Biol Bull. 2017;232:91–100. doi: 10.1086/692717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096. doi: 10.1126/science.1258096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Momose T, Concordet JP. Diving into marine genomics with CRISPR/Cas9 systems. Mar Genomics. 2016;30:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.margen.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikmi A, McKinney SA, Delventhal KM, Gibson MC. TALEN and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in the early-branching metazoan Nematostella vectensis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5486. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Servetnick MD, et al. Cas9-mediated excision of Nematostella brachyury disrupts endoderm development, pharynx formation and oral-aboral patterning. Development. 2017;144:2951–2960. doi: 10.1242/dev.145839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gahan JM, et al. Functional studies on the role of Notch signaling in Hydractinia development. Dev Biol. 2017;428:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Yu LC. Single-cell microinjection technology in cell biology. BioEssays. 2008;30:606–610. doi: 10.1002/bies.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilles AF, Averof M. Functional genetics for all: Engineered nucleases, CRISPR and the gene editing revolution. Evodevo. 2014;5:43. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-5-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrison PL, et al. Mass spawning in tropical reef corals. Science. 1984;223:1186–1189. doi: 10.1126/science.223.4641.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baird AH, Guest JR, Willis BL. Systematic and biogeographical patterns in the reproductive biology of scleractinian corals. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2009;40:551–571. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keith SA, et al. Coral mass spawning predicted by rapid seasonal rise in ocean temperature. Proc Biol Sci. 2016;283:20160011. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollock FJ, et al. Coral larvae for restoration and research: A large-scale method for rearing Acropora millepora larvae, inducing settlement, and establishing symbiosis. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3732. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rentzsch F, Fritzenwanker JH, Scholz CB, Technau U. FGF signalling controls formation of the apical sensory organ in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. Development. 2008;135:1761–1769. doi: 10.1242/dev.020784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinigaglia C, Busengdal H, Lerner A, Oliveri P, Rentzsch F. Molecular characterization of the apical organ of the anthozoan Nematostella vectensis. Dev Biol. 2015;398:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strader ME, Aglyamova GV, Matz MV. Molecular characterization of larval development from fertilization to metamorphosis in a reef-building coral. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:17. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4392-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelmanson IV, Matz MV. Molecular basis and evolutionary origins of color diversity in great star coral Montastraea cavernosa (Scleractinia: Faviida) Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:1125–1133. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alieva NO, et al. Diversity and evolution of coral fluorescent proteins. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Angelo C, et al. Blue light regulation of host pigment in reef-building corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2008;364:97–106. [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Angelo C, et al. Locally accelerated growth is part of the innate immune response and repair mechanisms in reef-building corals as detected by green fluorescent protein (GFP)-like pigments. Coral Reefs. 2012;31:1045–1056. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shinzato C, Shoguchi E, Tanaka M, Satoh N. Fluorescent protein candidate genes in the coral Acropora digitifera genome. Zool Sci. 2012;29:260–264. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gittins JR, D’Angelo C, Oswald F, Edwards RJ, Wiedenmann J. Fluorescent protein-mediated colour polymorphism in reef corals: Multicopy genes extend the adaptation/acclimatization potential to variable light environments. Mol Ecol. 2015;24:453–465. doi: 10.1111/mec.13041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasuoka Y, Shinzato C, Satoh N. The mesoderm-forming gene brachyury regulates ectoderm-endoderm demarcation in the coral Acropora digitifera. Curr Biol. 2016;26:2885–2892. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paix A, Folkmann A, Rasoloson D, Seydoux G. High efficiency, homology-directed genome editing in Caenorhabditis elegans using CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Genetics. 2015;201:47–54. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.179382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho SW, Lee J, Carroll D, Kim J-S, Lee J. Heritable gene knockout in Caenorhabditis elegans by direct injection of Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoproteins. Genetics. 2013;195:1177–1180. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.155853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S, Kim D, Cho SW, Kim J, Kim J-S. Highly efficient RNA-guided genome editing in human cells via delivery of purified Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Genome Res. 2014;24:1012–1019. doi: 10.1101/gr.171322.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung YH, et al. Highly efficient gene knockout in mice and zebrafish with RNA-guided endonucleases. Genome Res. 2014;24:125–131. doi: 10.1101/gr.163394.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang WY, et al. Efficient genome editing in zebrafish using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:227–229. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ansai S, Kinoshita M. Targeted mutagenesis using CRISPR/Cas system in medaka. Biol Open. 2014;3:362–371. doi: 10.1242/bio.20148177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo X, et al. Efficient RNA/Cas9-mediated genome editing in Xenopus tropicalis. Development. 2014;141:707–714. doi: 10.1242/dev.099853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang X, et al. Rapid and highly efficient mammalian cell engineering via Cas9 protein transfection. J Biotechnol. 2015;208:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zu Y, et al. Biallelic editing of a lamprey genome using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23496. doi: 10.1038/srep23496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jao L-E, Wente SR, Chen W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308335110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, et al. One-step generation of mice carrying mutations in multiple genes by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Cell. 2013;153:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kistler KE, Vosshall LB, Matthews BJ. Genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9 in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Cell Rep. 2015;11:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodgers K, McVey M. Error-prone repair of DNA double-strand breaks. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231:15–24. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayward DC, Grasso LC, Saint R, Miller DJ, Ball EE. The organizer in evolution-gastrulation and organizer gene expression highlight the importance of Brachyury during development of the coral, Acropora millepora. Dev Biol. 2015;399:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kenkel CD, et al. Development of gene expression markers of acute heat-light stress in reef-building corals of the genus Porites. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Strader ME, Davies SW, Matz MV. Differential responses of coral larvae to the colour of ambient light guide them to suitable settlement microhabitat. R Soc Open Sci. 2015;2:150358. doi: 10.1098/rsos.150358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meyer E, et al. Sequencing and de novo analysis of a coral larval transcriptome using 454 GSFlx. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:219. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Craggs J, et al. Inducing broadcast coral spawning ex situ: Closed system mesocosm design and husbandry protocol. Ecol Evol. 2017;7:11066–11078. doi: 10.1002/ece3.3538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mazo-Vargas A, et al. Macroevolutionary shifts of WntA function potentiate butterfly wing-pattern diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:10701–10706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708149114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.