Abstract

Currently, classification of alcohol use disorder (AUD) is made on clinical grounds; however, robust evidence shows that chronic alcohol use leads to neurochemical and neurocircuitry adaptations. Identifications of the neuronal networks that are affected by alcohol would provide a more systematic way of diagnosis and provide novel insights into the pathophysiology of AUD. In this study, we identified network-level brain features of AUD, and further quantified resting-state within-network, and between-network connectivity features in a multivariate fashion that are classifying AUD, thus providing additional information about how each network contributes to alcoholism.

Resting-state fMRI were collected from 92 individuals (46 controls and 46 AUDs). Probabilistic Independent Component Analysis (PICA) was used to extract brain functional networks and their corresponding time-course for AUD and controls. Both within-network connectivity for each network and between-network connectivity for each pair of networks were used as features. Random forest was applied for pattern classification.

The results showed that within-networks features were able to identify AUD and control with 87.0% accuracy and 90.5% precision, respectively. Networks that were most informative included two; Executive Control Networks (ECN), and Reward Network (RN). The between-network features achieved 67.4% accuracy and 70.0% precision. The between-network connectivity between RN-Default Mode Network (DMN) and RN-ECN contribute the most to the prediction.

In conclusion, within-network functional connectivity offered maximal information for AUD classification, when compared with between-network connectivity. Further, our results suggest that connectivity within the ECN and RN are informative in classifying AUD. Our findings suggest that machine-learning algorithms provide an alternative technique to quantify large-scale network differences and offer new insights into the identification of potential biomarkers for the clinical diagnosis of AUD.

Keywords: fMRI, Functional Connectivity, Resting state, Alcohol dependence, ICA

Introduction

Alcohol dependence is a chronic relapsing disorder with an impulsive drive toward alcohol consumption and an inability to inhibit its consumption despite negative consequences. Currently, AUD is a diagnosis that is based on clinical history, not based on underlying neurobiology or neuronal network abnormalities. It is important to identify the brain biomarkers that can be used to improve diagnostic identification of alcoholism at various stages and predicting treatment outcomes.

There is growing interest in studying functional connectivity among brain networks in alcoholism and drug addiction. Resting state functional connectivity (rs-FC), which is measured by temporal coherence in low-frequency fluctuations of distinct brain regions, has been shown to be an effective method in studying functional organization of the brain. Researchers have shown disrupted functional integration is associated with chronic alcohol use by using traditional group-level analysis [1,2]. However, the group-level analysis cannot quantify the complex interactions of both within- and between-network connectivity and identify the subtle difference of each individual. Machine-learning algorithms provide alternative tools to look into multivariate patterns in the data, and help us move from group-level analysis to case-by-case individual-level analysis [3,4].

Machine-learning approach has been used on resting state fMRI data in classifying schizophrenia [4], autism [5–7], Alzheimer’s disease [8], attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [9], Parkinson disease [10], major depressive disorder [11], and epilepsy [12] etc. To date, only a few studies have explored the addiction field using machine learning approaches, for example, in heavy cannabis users [13], Smokers [3], and heroin-dependent individuals [14]. However, no study to date has explored rs-FC using machine learning in classifying AUD.

In this study, we sought to identify both within-network and between-network connectivity features in a multivariate fashion that are predictive of alcohol dependence. We hypothesized that the machine-learning algorithms can identify the biomarkers which are involved in AUD. Furthermore, we also hypothesized that subtle differences in the within-network connectivity and between-network connectivity between AUD and controls during the resting state could be revealed and provide quantitative information about how each network contributes to AUD. More specifically, we are interested in answering the following questions: 1) whether rs-FC features are able to distinguish between AUD and controls; 2) Which brain-based features are able to diagnose and are potentially predictive of alcohol dependence? and 3) Can we quantify how well they identify AUD and what are the best neuronal predictors of AUD?

Methods and Materials

2.1 Participants

Forty-six controls and 46 short-term abstinent patients were recruited by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism part of the National Institutes of Health, USA (Table 1). Healthy controls were recruited through newspaper advertisements and information notices distributed in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. Patients were recruited from the 1-SE inpatient alcohol withdrawal treatment unit at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Alcohol detoxification procedure generally took 3 to 10 days after admission in the inpatient unit. The fMRI session was conducted following hospitalization for at least 1 week (7 to 43 days, Table 1). Written informed consent to the study was obtained from all of subjects, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical profile of the participants in this study

| AUD | Control | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants | 46 | 46 | |

| Age, years | 40.4 (±9.7) | 32.0 (±8.9) | p<0.01 |

| Smokers (N/%) | 30 (65.2%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Gender (N/%) | p=0.13 | ||

| Male | 33 (71.7%) | 26 (56.5%) | |

| Female | 13 (28.3%) | 20 (43.5%) | |

| Race (N/%) | |||

| Caucasian | 25 (54.3%) | 29 (63.0%) | |

| Africa-American | 19 (41.2%) | 13 (28.3%) | |

| Asian | 2 (4.3%) | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Days of withdrawal before MRI | 26.9 (±8.7) | N/A |

2.2 Assessments

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID) was administered to all participants to determine diagnoses of alcohol dependence as well as other substance use and psychiatric disorders. A 90 day Timeline Followback (TLFB) calendar was used to measure the frequency and amount of drinking for all subjects. The amount of lifetime alcohol intake for controls was measured by using the lifetime drinking history. A smoking questionnaire was used to determine the amount and frequency of a participant’s cigarette use.

2.3 Exclusionary criteria

Exclusionary criteria included pregnancy, claustrophobia, significant neurological, or medical diagnoses. Subjects were also excluded if they had ferromagnetic objects in the body, a positive HIV test, active suicidal or homicidal ideations, or were currently taking psychotropic medication. A failed neuromotor examination was exclusionary as well. Participants were instructed not to consume any alcohol for 24 hours and no more than half a cup of caffeinated beverages 12 hours prior to each scanning visit. Participants could not participate if they had a positive alcohol breathalyzer or urine drug screen on the day of the scan. Controls were excluded if they met criteria for any current or past AUD. All subjects were required to be right handed and deemed physically healthy by a clinician. Participants with AUD could not have severe symptoms of alcohol withdrawal defined by a Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol Scale (CIWA) score of greater than 8.

2.4 MRI Data acquisition

Five minutes of closed-eyes rs-fMRI (150 volumes) were collected using a 3T SIEMENS Skyra MRI scanner. Resting state fMRI datasets were collected using a single-shot gradient echo planar imaging pulse sequence with thirty-six axial slices acquired parallel to the anterior/posterior commissural line (TR = 2000ms, TE = 30ms, flip angle=90°, 3.75 mm × 3.75 mm × 3.8 mm voxels). High-resolution T1-weighted 3-D structural scans were acquired for each subject using an MPRAGE sequence (TR = 1200ms TE =30ms, 256 × 256 matrix, 128 axial slices).

2.5 rs-fMRI data pre-processing

Using Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB)’s Software Library (FSL) package (www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) we applied; 1) slice timing correction for interleaved acquisitions using interpolation with a Hanning windowing kernel; 2) motion correction using Motion Correction using FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (MCFLIRT); 3) non-brain removal using Brain Extraction Tool (BET); 4) spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of full width at half maximum 5mm; 5) grand-mean intensity normalization of the entire 4D dataset by a single multiplicative factor, the size of the voxels is 4×4×4 mm3; 6) high-pass temporal filtering (Gaussian-weighted least-squares straight line fitting, with sigma=50s); 7) removing trends and regressing out a set of nuisance variables such as motion parameters and it’s derivatives, signals from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and white matter using fsl_glm; and 8) registration to high resolution structural MNI standard space images using the FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool (FLIRT). We used a stringent threshold for head motion in the pre-processing step. Subjects with head motion greater than 0.3 mm for translation and 0.3° for rotation between consecutive TRs were removed from the study. The head motion was not different between the two groups.

2.6 rs-fMRI connectivity analysis

1. Feature extraction

Extracting brain functional networks and their corresponding time-course is the first step to extract both types of proposed features. We applied Probabilistic Independent Component Analysis (PICA) by using the Multivariate Exploratory Linear Decomposition into Independent Components (MELODIC) toolbox of the FSL for this purpose. ICA, a multivariate data-driven method which is a blind source separation method where individual regions in a given network show tight functional connectivity which enables isolation of a set of signals from their linear mixtures, and has yielded fruitful results with fMRI data [15]. ICA estimates maximally independent components using independence measures based on higher order statistics. Compared to general linear model approaches, ICA requires no specific temporal model (task-based design matrix), making it ideal for analyzing resting state data. Spatial components resulting from spatial ICA are maximally spatially independent but their corresponding time-courses can show a considerable amount of temporal dependency.

In order to create an unbiased template of resting-state networks, a group ICA was performed on all 92 AUD and controls. A temporal concatenation tool in MELODIC was used to derive group level components across all subjects. Pre-processed data were whitened and projected into a 37-dimensional subspace using PICA where the number of dimensions was estimated using an objective estimation of the amount of Gaussian noise through Bayesian analysis of the true dimensionality of the data (the number of activation and non-Gaussian noise sources) [16]. The whitened observations were decomposed into sets of vectors which describe signal variation across the temporal domain (time-courses) and across the spatial domain (maps) by optimizing for non-Gaussian spatial source distributions using a fixed-point iteration technique. These FC components maps were standardized into z statistic images via a normalized mixture model fit, thresholded at z > 7, cluster size > 30 voxels.

Two criteria were used to remove biologically irrelevant components: (1) those representing known artifacts such as motion, and high-frequency noise; and (2) those with connectivity patterns not located mainly in gray matter. Networks of interest were identified as anatomically and functionally classical RSNs upon visual inspection. This procedure ended up with 32 component maps (Figure 1). The between-subject analysis was carried out using dual regression, a regression technique which back-reconstructs each group level component map at the individual subject level [16]. This technique allows for voxel-wise comparisons of rs-FC by carrying out the following steps: regresses the group level spatial maps into each individual’s 4D dataset to obtain a set of timeseries and then regresses those individual level timeseries into the same 4D dataset to obtain a subject-specific set of spatial maps. The Harvard-Oxford cortical and subcortical atlases incorporated in FSL were used to identify the anatomical regions of the resulting PICA maps. The FSL Cluster tools were used to report information about clusters in the selected maps. The connectivity maps were overlaid onto the mean standardized structural T1 1-mm MNI template and visualized using Mricogl.

Figure 1.

Spatial maps of 32 independent components grouped into 5 categories (Different colors represent different network sub-components in each category for A to D): A: default-model networks (3 components). B: Visual networks (7 components) C: Sensorimotor networks (6 components) D: executive control networks (12 components) E: all other networks (4 components) including salience network (Green), subcortical network (Blue), auditory network (Violet), cerebellar (Yellow)

2. Feature selection

Within-network connectivity

The group level components maps thresholded at z > 7, cluster size > 30 voxels were used as masks on the subject-specific maps. The averaged z value within each mask was calculated as within-network connectivity features, thus in total 32 within-network connectivity features were extracted for each subject.

Between-network connectivity

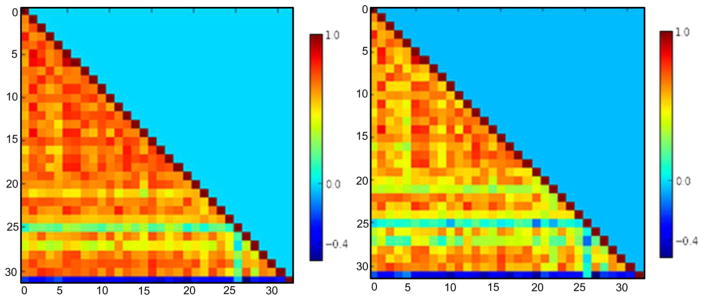

Even though all component maps are spatially independent, time series of the components may still have significant temporal correlations. Network interaction comparisons (Correlation coefficients, Pearson’s r) between each pair of networks were computed for each subject time series that were obtained by the first stage of the dual regression procedure. These correlation coefficients were Fisher z-transformed and used as between-network connectivity features (496 features, figure 2).

Figure 2.

Between-network functional connectivity features: correlation coefficients matrices between each pair of networks in AUD (left) and controls (right)

The differences in age and gender between AUD and controls do not make for ideal comparisons. To minimize the potential confounding influence of age and gender in these results, we performed a covariate analysis of age and gender for each network of interest [17].

2.7 Classification

Random forest was applied to both within-network and between-network functional connectivity from the 46 AUD and 46 controls.

1. Random Forest

Random forest, an ensemble machine-learning algorithm, builds a group of weak learners of decision trees to form a “strong learner”, thereby improving the generalization ability of the classifier (Breiman 2001). In constructing the ensemble of trees, random forest uses two levels of randomness: first each tree uses a bootstrapped version of the training data (bagging). Specifically, about 66% of the training data was used for each tree with replacement; the remaining training data was used to estimate error and variable importance. A second level of randomness is added at each node when growing a decision tree by randomly selecting a subset of variables to split. At each internal node, a best feature among a random subset of features is selected so as to maximize the reduction of label impurity, typically measured with the class entropy. The process is recursively repeated until the tree has either reached a predefined depth or the number of samples in a node falls below a threshold, or all the samples belong to the same class. The number of trees in the ensemble and the number of variables selected at each node are the two main parameters of the random forest algorithm. The random forest has been proven to achieve good performance with a different variety of datasets and has important advantages over other techniques in terms of its ability to handle highly non-linear biological data, robustness to noise, tuning simplicity (compared to other ensemble learning algorithms), and opportunity for efficient parallel processing [18]. Classification of a new instance can be made by taking the majority vote from all the decision trees. It’s often helpful to calculate relative importance or contribution of each feature in predicting the label. Random forest has several ways of constructing variable importance: 1) mean decrease impurity, i.e. average of the accumulated decrease in node impurity over all trees for each feature or 2) mean decrease accuracy, i.e. the decrease in accuracy on out-of-bag (OOB) samples by randomly permuting values for each feature. In this work we will use the first method to measure feature importance. We used the python package scikit random forest [19] with the parameters for the number of trees (ntree = 600) and the number of features analyzed at each node to find the best split (for a dataset with p features, square root of p are used in each split).

2. Feature elimination

When the total number of variables is large, but the fraction of relevant variables is small, then random forests are likely to perform poorly due to the small chances that the relevant variables being selected. Moreover, when the dimensionality of feature space increases, the available observations become sparse which causes the problem of “curse of dimensionality” which refers to the phenomenon that as dimensionality of data increases, the available data becomes sparse, thus it is difficult to extract a meaningful conclusion from the data set. Additional steps such as feature selection and reduction are needed to avoid curse of dimensionality. Random forest can be considered as an effective feature selection algorithm by using the feature importance scores. In the current study, random forest was first performed on all features, and the ranking of average feature importance was used for feature elimination.

3. Classification performance

The performance of the classifier was then evaluated based on accuracy, and precision. The prediction data included true positive (TP), false negative (FN), true negative (TN), and false positive (FP) classifications. The accuracy and precision were computed using the following formulas:

To explore an optimal set of feature variables, datasets were entered individually, and the prediction accuracy was computed by using leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). In LOOCV, one subject’s data are left out of the dataset, and the random forest creates an optimal classifier using the remaining data. The classifier predicts the label (AUD or control) of the one subject who was left out, and the accuracy of this prediction is assessed. This procedure was repeated as many times as the number of subjects, with a different subject being left out each time; finally, total accuracy was computed for each category (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The procedure of feature extraction and pattern classification

To test whether classification performance was significantly above chance, we randomly assign each subject as AUD or control and used this dataset to train and test each classifier. This procedure was carried out 1000 time and obtained the distribution of accuracy (mean= 0.486; std= 0.071) and precision (mean=0.51; std=0.048). Z-tests were used to test the statistical significance between the actual accuracy and precision values and the randomly generated values. Whether the actual accuracy and precision values were 2 standard deviations above the generated values were also tested.

Results

We trained and tested the classifier to distinguish the patterns of resting state functional connectivity between AUD and controls. Table 2 summarized the performance of the random forest with no feature elimination, 50% feature elimination and 90% feature elimination.

Table 2.

Performance of the random forest with no feature elimination, 50% feature elimination and 90% feature elimination (*two standard deviation above chance)

| Within-RSN | Between-RSN | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No feature elimination | Accuracy | 72.80%* | 54.30% |

| Precision | 76.90%* | 54.50% | |

| 50% feature elimination | Accuracy | 76.10%* | 64.10%* |

| Precision | 80.00%* | 64.40%* | |

| 90% feature elimination | Accuracy | 87.00%* | 67.40%* |

| Precision | 90.50%* | 70.00%* |

As can be seen from the Table 2, classification performance significantly improved with feature elimination. To identify the features maximally contributing to the classifier, we extracted the features that were utilized in the classifier following 90% feature elimination.

The within-network features that have the strongest predicting power were found in: executive control network (ECN1) including orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), middle frontal gyrus (MFG), frontal pole (FP) and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG); ECN2 including MFG, FP, IFG anterior cingulate gyrus (ACC); and reward network (RN) including thalamus, nucleus accumbens, putamen, and caudate (Figure 4). The stability of within-network features was tested using leave-one-out cross-validation and the results were presented in Figure 5. The three most important features were consistent across different feature elimination scenarios; thus, they can be used as stable features predictive of AUD and controls. The between-network features that have shown the strongest predicting power were found between Default Mode Network (DMN1) and RN, and between ECN and RN. The stability of between-network features was presented in Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Within-network features maximally contributing to classification performance including ECN1 (Violet), ECN2 (Blue), RN (Cyan)

Figure 5.

The stability of within-network features that have the strongest predicting power (ECN1, RN and ECN2). The mean and standard error of feature importance of 92 random forests by using leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) were calculated and presented in the figure.

Figure 6.

The stability of between-network features that have the strongest predicting power. The prediction accuracy was computed 92 times by using leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). The mean and standard error of feature importance of 92 random forests by using leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) were presented in the figure.

Discussion

Alcohol use disorder is a complex disease with multifaceted components, severity, and will likely lead to chronic adaptation of neurotransmission and neuronal circuits. Recently, more focus has been devoted to the alterations of resting state and functional connectivity in AUD [1,20]. To our knowledge, no study has applied machine-learning algorithms to determine the utility of the functional connectivity alterations in diagnosing the severity of the AUD progress or ultimately predicting those at risk. This is the first attempt to evaluate the application of a machine-learning approach to analyze the resting state functional connectivity of short-term abstinent AUD and controls. First, we showed that the rs-FC features are able to automatically discriminate AUD from controls. Second, we quantitatively compared the performance of within-network and between-network features that contribute most to the classifier and identified the features best detecting alcohol dependence. With the help of the feature elimination method, our results showed that the within-network features distinguish AUD from controls with 87% accuracy and 90.5% precision, higher than the performance using between-network features (67.4% accuracy and 70.0% precision). The within-networks contributed the most including two Executive Control Networks (ECN), and Reward Network (RN). The between-network connectivity between RN and Default Mode Network (DMN), RN and ECN contributes the most to the prediction.

Researchers have shown disrupted functional integration is associated with AUD. For example, several studies found decreased functional connectivity in AUD when compared with controls, such as DMN, ECN, SN and RN [2,21–23]. On the other hand, several studies found increased functional connectivity in AUD, compared with controls. For example, patients with AUD also showed significant increased regional homogeneity in the posterior cingulate cortex, insula and reduction in the ACC, when compared with controls [24]. Significant increased functional connectivity was found in DMN, ECN, SN, and attention network in AUD [21]. Long-term abstinent alcoholic subjects showed increased functional connectivity in ECN [1]. In our previous study, we found significant increased within-network FC in SN, DMN, orbitofrontal cortex (OFCN), left- ECN and amygdala-striatum (ASN) networks in AUD when compared with controls [20]. These studies converge to support that the dysfunctional connectivity was associated with sustained alcohol use. However, even though group-level functional connectivity differences were found between AUD and controls, they may not be used as biomarkers to classify severity of the disease progress or ultimately predicting relevant future events, such as relapse. In the current study, adding to our previous findings, we found that two ECNs, and the RN have the strongest classification power in distinguishing AUD from controls (one ECN overlapped with the previous OFCN, the other ECN overlapped with the previous LECN, and the RN overlapped with the previous ASN). We observed that within-network FC measures offered maximal information for identifying alcoholism, suggesting that connectivity measures within the ECN and RN are particularly informative in detecting alcoholism. The classification performance improved with feature elimination suggesting that these few networks performed outstandingly among all other networks (87% accuracy and 90.5% precision). Also, the rank of the networks did not change when doing the LOOCV tests under different feature elimination cases suggesting that the contribution of the features was very stable and robust. Therefore, dysfunction of the ECN1 including OFC, MFG, the RN including the thalamus, accumbens, putamen, caudate, and the ECN2 involving MFG, FP, IFG and ACC may be part of the underlying neurobiology of addiction. On the other hand, the classification performance using between-network features only achieved 67.4% accuracy and 70.0% precision. This lack of robustness was also reflected in the fact that the rank of the network coupling also changed when doing the LOOCV tests under different feature elimination cases. These results suggested that the between-network coupling might only be a modest indicator to distinguish AUD from controls given the sample size we have. This may be due to the fact that we only used correlation to measure the weak dependency among network time courses. Therefore, we might miss such weak dependency if two time courses have time-lagged correlation. As such, alternative methods such as Granger causality [25], Autoregressive of model order one (AR1) [26], or dynamic causal modeling [27] may be applied to address this issue.

It is important to understand whether the disrupted functional connectivity was specific to AUD or addiction in general. We, therefore, first tested the influence of cigarette smoking on AUD since 65% of the AUD were smokers in our samples. Additional group analysis on AUD with smoking and AUD without smoking was conducted. Functional connectivity strength did not differ between these two groups in any of the networks. Thus, no influence was found by this confounding factor in the case group. In addition, our results are consistent with another machine-learning study predicting smoking status [3], in which they also found within-network connectivity including ECN, FP and higher order networks is most informative in predicting nicotine dependence. These results may indicate a shared neuro-pathway for both AUD and nicotine dependence. Further investigation is need in comorbidity of AUD and other addiction disorders.

Koob et al., 2010 have proposed that addiction is composed of three stages including binge/intoxication stage, withdrawal/negative affect stage and preoccupation/anticipation stage [28]. Each stage involves discrete circuits: ventral stratum and ventral tegmental regions for binge/intoxication stage, amygdala in the withdrawal stage, and a wide range of distributed network including the OFC-striatum, PFC, amygdala, hippocampus, and insula involved in craving and the IFG, ACC, DLPFC for inhibitory control. In the current study, we investigated the functional connectivity in short-term abstinent AUD participants who were in the third stage of addiction, and our results provided evidence that the machine-learning methods may offer a diagnostic tool for identifying the brain biomarkers to distinguish AUD from controls. In the future, this could be used for predicting and estimating the trajectory of AUD, such as identifying those at the first stage of addiction and are at risk of developing AUD, or ultimately predicting relapse and the treatment outcomes based on rs-FC phenotypes. In the future, these individual-level brain features can be integrated with task-based brain features, behavior measures, clinical measures, genetic and environmental factors using the multivariate approach to get a better understanding of cause and effect of AUD. For example, in a longitudinal study that identifies predictors of adolescent substance misuse, Whelan et al. 2014 not only showed the potential of neuroimaging as a tool to generate intermediate endophenotypes, but also highlighted the importance of combining neuroimaging with a wide range of potential causal factors including higher cognitive factors, personality, environmental factors, life experiences, genetics etc. to understand the mechanism underlying addiction [29]. In this study, our results showed that with the help of machine-learning techniques we could deepen our understanding and better quantify the contribution of each brain networks to alcoholism.

Limitation

There are several potential limitations in our study that should be taken into account carefully. First, clinical heterogeneity could have confounded results. Alcoholism is a highly comorbid disease, as in most cases it is coupled with current or past use of other drugs (such as cocaine, cannabis, or opioid etc.) and psychiatric comorbidities. However, since the subjects in the current study had different types of drug use or psychiatric disorders, it is unlikely that any particular one of the comorbidities might have contributed significantly to our results. Therefore, alcohol use disorder is still the dominant factor contributing to the functional connectivity difference between case and control. Second, the AUD and control groups were not age and gender matched. Consequently, we statistically controlled for age, in addition to gender, in our analysis. To ensure that the classification performance was not affected by these factors, another analysis was carried out in which we used age, gender, and brain-based features in an analysis, and found age and gender features did not change the performance of classification. Future research with case and control groups matched for age and gender would increase the reliability of the current results. Finally, for those participants with AUD having severe withdrawal symptoms during the first few days after stopping alcohol, benzodiazepines were given as needed as guided by the CIWA-Ar and vital signs monitoring. Although the fMRI session was conducted following hospitalization for at least 1 week (7 to 43 days), the benzodiazepines may still have had effects on the functional connectivity of the brain. Further tests are needed in this regard. Other limitations include using relatively short resting-state scan time (5 mins). Our data warrant replication in larger samples with longer scan time.

In conclusion, within-network functional connectivity offered maximal information for predicting AUD status. Further, our results suggest that connectivity within the ECN and RN might be informative in predicting AUD. Further development of this approach might also provide useful information for therapeutic interventions or treatment effectiveness. More attention should be given to the patterns of information transmission and processing between these networks in AUD and perhaps other addictions. These findings may shed light on the mechanism underlying addiction. Our findings suggest that machine-learning-based approaches to classifying rs-FC offer an additional and valuable technique for understanding large-scale differences in addiction-related neurobiology.

Highlights.

Diagnosis of alcohol use disorder using resting state functional connectivity

Quantify resting-state within-network and between-network connectivity features in a multivariate fashion

Offer new insights into the identification of potential biomarkers for the clinical diagnosis of AUD

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism intramural funding.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors acknowledge that there is no conflict of biomedical financial interests in performing this study or in preparing this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Camchong J, Stenger VA, Fein G. Resting-state synchrony in short-term versus long-term abstinent alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:794–803. doi: 10.1111/acer.12037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chanraud S, Pitel AL, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Disruption of functional connectivity of the default-mode network in alcoholism. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:2272–2281. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pariyadath V, Stein EA, Ross TJ. Machine learning classification of resting state functional connectivity predicts smoking status. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:425. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arbabshirani MR, Kiehl KA, Pearlson GD, Calhoun VD. Classification of schizophrenia patients based on resting-state functional network connectivity. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:133. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plitt M, Barnes KA, Martin A. Functional connectivity classification of autism identifies highly predictive brain features but falls short of biomarker standards. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;7:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iidaka T. Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging and neural network classified autism and control. Cortex. 2015;63:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Lynch CJ, Khouzam A, Phillips J, et al. Salience network-based classification and prediction of symptom severity in children with autism. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:869–879. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen G, Ward BD, Xie C, Li W, Wu Z, et al. Classification of Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal cognitive status with large-scale network analysis based on resting-state functional MR imaging. Radiology. 2011;259:213–221. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.dos Santos Siqueira A, Biazoli CE, Junior, Comfort WE, Rohde LA, Sato JR. Abnormal functional resting-state networks in ADHD: graph theory and pattern recognition analysis of fMRI data. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:380531. doi: 10.1155/2014/380531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long D, Wang J, Xuan M, Gu Q, Xu X, et al. Automatic classification of early Parkinson’s disease with multi-modal MR imaging. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundermann B, Olde Lutke Beverborg M, Pfleiderer B. Toward literature-based feature selection for diagnostic classification: a meta-analysis of resting-state fMRI in depression. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:692. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Cheng W, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Lu W, et al. Pattern classification of large-scale functional brain networks: identification of informative neuroimaging markers for epilepsy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng H, Skosnik PD, Pruce BJ, Brumbaugh MS, Vollmer JM, et al. Resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals distinct brain activity in heavy cannabis users - a multi-voxel pattern analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:1030–1040. doi: 10.1177/0269881114550354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Tian J, Yuan K, Liu P, Zhuo L, et al. Distinct resting-state brain activities in heroin-dependent individuals. Brain Res. 2011;1402:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calhoun VD, Liu J, Adali T. A review of group ICA for fMRI data and ICA for joint inference of imaging, genetic, and ERP data. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, Smith SM. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:1001–1013. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck A, Wustenberg T, Genauck A, Wrase J, Schlagenhauf F, et al. Effect of brain structure, brain function, and brain connectivity on relapse in alcohol-dependent patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:842–852. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menze BH, Kelm BM, Masuch R, Himmelreich U, Bachert P, et al. A comparison of random forest and its Gini importance with standard chemometric methods for the feature selection and classification of spectral data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham A, Pedregosa F, Eickenberg M, Gervais P, Mueller A, et al. Machine learning for neuroimaging with scikit-learn. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:14. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2014.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu X, Cortes CR, Mathur K, Tomasi D, Momenan R. Model-free functional connectivity and impulsivity correlates of alcohol dependence: a resting-state study. Addict Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/adb.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller-Oehring EM, Jung YC, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Schulte T. The Resting Brain of Alcoholics. Cereb Cortex. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiland BJ, Sabbineni A, Calhoun VD, Welsh RC, Bryan AD, et al. Reduced left executive control network functional connectivity is associated with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:2445–2453. doi: 10.1111/acer.12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camchong J, Stenger A, Fein G. Resting-state synchrony in long-term abstinent alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim H, Kim YK, Gwak AR, Lim JA, Lee JY, et al. Resting-state regional homogeneity as a biological marker for patients with Internet gaming disorder: A comparison with patients with alcohol use disorder and healthy controls. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deshpande G, LaConte S, James GA, Peltier S, Hu X. Multivariate Granger causality analysis of fMRI data. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:1361–1373. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison L, Penny WD, Friston K. Multivariate autoregressive modeling of fMRI time series. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1477–1491. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stevens MC, Kiehl KA, Pearlson GD, Calhoun VD. Functional neural networks underlying response inhibition in adolescents and adults. Behav Brain Res. 2007;181:12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whelan R, Watts R, Orr CA, Althoff RR, Artiges E, et al. Neuropsychosocial profiles of current and future adolescent alcohol misusers. Nature. 2014;512:185. doi: 10.1038/nature13402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]