Abstract

The prevalence of depression rises steeply during adolescence. Family processes have been identified as one of the important factors that contribute to affect (dys)regulation during adolescence. In this study, we explored the affect expressed by mothers, fathers, and adolescents during a problem solving interaction and investigated whether the patterns of the affective interactions differed between families with depressed adolescents and families with non-depressed adolescents. A network approach was used to depict the frequencies of different affects, concurrent expressions of affect, and the temporal sequencing of affective behaviors among family members. The findings show that families of depressed adolescents express more anger than families of non-depressed adolescents during the interaction. These expressions of anger co – occur and interact across time more often in families with a depressed adolescent than in other families, creating a more self-sustaining network of angry negative affect in depressed families. Moreover, parents’ angry and adolescents’ dysphoric affect follow each other more often in depressed families. Taken together, these patterns reveal a particular family dynamic that may contribute to vulnerability to, or maintenance of, adolescent depressive disorders. Our findings underline the importance of studying affective family interactions to understand adolescent depression.

Keywords: family interaction, adolescence, depression, dynamic network, affect

The prevalence of depression rises steeply during adolescence (Birmaher et al., 1996; Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 2006; Seeley & Lewinsohn, 2008). Also, adolescents that have suffered one or more depressive episodes are at risk of subsequent episodes (33% within the next 4 years; Lewinsohn, Clarke, Seeley, & Rohde, 1994) and of developing comorbid conditions, even into adulthood (Lewinsohn, Rohde, Klein, & Seeley, 1999). Adolescent depression has severe consequences for current and future psychosocial functioning. It impairs academic performance, increases social difficulties, and is associated with poor self-reported social well-being (Verboom, Sijtsema, Verhulst, Penninx, & Ormel, 2014). These serious negative life-time consequences underline the urgency to discover the mechanisms that precipitate or maintain depressive disorders during adolescence, a life period in which these disorders typically emerge for the first time (Lewinsohn et al., 1994).

Multiple authors have pointed out that within-person neurological, cognitive and socioemotional changes may explain why some adolescents develop depression and why adolescence is such a crucial period (e.g., Allen & Sheeber, 2008a). However, several theories and recent research also emphasize the role of contextual factors, especially interpersonal relationships, in the emergence of depression. Notably, the occurrence of depression in children and adolescents has been linked to numerous family factors. The importance of the family environment for the development of psychopathology in general and depression in particular is evident for several reasons.

First, as emphasized in theories on developmental psychopathology, the context in which development takes place needs to be taken into account (e.g., Cicchetti & Toth, 1998; Cummings, Davies, & Campbell, 2000). Family is the primary psychological environment a child grows up in, and characteristics of this environment and the mutual interactions that take place in it, determine whether a child grows up in a loving and caring or in a rather stressful and threatening environment. Indeed, a host of research shows that parental characteristics, such as quality of the attachment relation (e.g., Brenning, Soenens, Braet, & Bosmans, 2012; Brumariu & Kerns, 2010; Dujardin et al., 2016), parental psychopathology (e.g., Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Loon, Ven, Doesum, Witteman, & Hosman, 2014), quality of the relationship of the parents (e.g., Davies & Cummings, 1994), parenting styles and practices (e.g., Lipps et al., 2012; Milevsky, Schlechter, Netter, & Keehn, 2007), determine risk for depression, and that this risk is largely passed on through how parents and children mutually interact (Sheeber, Davis, Leve, Hops, & Tildesley, 2007).

Second, as argued by family systems theory, a family forms an emotional unit, a dynamic system in which the individual family members continuously influence each other, while shaping and being shaped by the structure of the family (Haefner, 2014; Minuchin, 1974). Emotional skills, for example, are to a large extent acquired during affective interactions in the family context: children learn to interpret the emotional expressions of significant others, to express their emotions in an appropriate manner, and to regulate their emotions adaptively depending on context (Hunter, Hessler, & Fainsilber Katz, 2008; Schwartz, Sheeber, Dudgeon, & Allen, 2012). Although emotional skills initially develop in infancy and early childhood, youth continue to learn and develop skills through adolescence. In this period, pubertal and neural developments trigger changes in cognitive and affective processes (Blakemore, 2012; DeRose & Brooks-Gunn, 2008; Steinberg, 2005) and in the adolescent’s social systems, which become more layered and complex (Allen & Sheeber, 2008b). The affect regulation strategies acquired during infancy and childhood might prove insufficient to face these new developmental challenges: “When the advent of novel emotional states precedes the development of the capacity to regulate them, adolescents may resemble unskilled drivers trying to maneuver a car that has just been turbo-charged by puberty” (Kesek, Zelazo, & Lewis, 2008, p. 135 referring to Dahl, 2004). Not surprisingly, this developmental phase goes hand in hand with an observable increase in the variability and instability of the affective behavior that is displayed in family interactions (Granic, Hollenstein, Dishion, & Patterson, 2003; Hollenstein, 2007; Lichtwarck-Aschoff, Kunnen, & van Geert, 2009). The adolescents need to reorganize their affect regulation strategies and skills or adopt new ones that are more appropriate for adult life. How adolescents navigate this is an important pathway linking family interactions to depression (Brenning et al., 2012; Schwartz et al., 2017).

To summarize, how parents and adolescents interact with one another is thought to provide a crucial environment that may create risk for depression, and offers a playground to learn how to deal with emotions. Obtaining a comprehensive picture of the nature and quality of parent-adolescent interaction is therefore of crucial importance to understand the role of family processes in depression. In this paper we aim to obtain a detailed view on how affective expressions are exchanged and potentially regulated during family interactions and how this may differ between families with a depressed adolescent and families with a non-depressed adolescent 1. To this end, we will use a novel dynamical network approach.

Affective Family Interactions

Affective family interactions are characterized by a number of features that need to be taken into account when studying their role in depression. First, affective family interactions evolve and unfold across time. Individuals’ affects change from one moment to the next, and dynamically impact each other’s affective behavior. To chart these fluctuations over time and the dynamics between them, one needs detailed information about affective behaviors by measuring them at many time points with only small time intervals between them (Walls & Schafer, 2005), resulting in so called “intensive longitudinal data” or “time series data” (Hamaker, Ceulemans, Grasman, & Tuerlinckx, 2015).

Second, although many studies focus on the mother-child relationship, for a more complete understanding, interactions with both parents should be taken into consideration. Indeed, adolescents may behave differently towards their fathers than towards their mothers (Allen, Kuppens, & Sheeber, 2012; Davis, Hops, Alpert, & Sheeber, 1998; Davis, Sheeber, Hops, & Tildesley, 2000) and the relationship between the adolescent and the parent depends on whether the other parent is present (Gjerde, 1986). Such triadic interactions, which constitute the smallest stable unit in family systems theory, are fundamentally different from dyadic interactions, for instance, because the third person forces the actors to split their attention and introduces new roles, such as “peacekeeper” or “withdrawn witness”(Hollenstein, Allen, & Sheeber, 2016).

Third, affective interactions, of course, may involve a host of different emotions, which may each elicit one another. As a consequence, to capture the richness of the affective exchange, preferably multiple affective states are considered when studying family interactions, going beyond mere valence-driven distinctions (i.e., positive vs. negative affect). Angry and dysphoric behavior, for example both indicate negative affect, but serve different functions in social interactions: Angry behavior is an aggressive, self-protecting affect likely to elicit reciprocity of anger from other family members, while dysphoric behavior is more likely to elicit sympathetic response and to suppress aggression (Parkinson, 1996; Van Kleef, De Dreu, & Manstead, 2010). Positive affect also needs to be taken into account, as it orients towards social bonds and enhances forming of positive relationships (Ramsey & Gentzler, 2015), while maladaptive regulation of positive affect is associated with depression (Werner-Seidler, Banks, Dunn, & Moulds, 2013; Yap, Allen, & Ladouceur, 2008).

Finally, the affective behavior of families themselves may differ in several respects. The overall emotionality (i.e., which affects are expressed and how frequently) might vary across families. Previous studies, for instance, reported that parent-adolescent relationships in depressed families are characterized by more negative and conflictual interaction and less positive feedback and support (Sheeber, et al., 2007; Thompson, McKowen, & Rosenbaum Asarnow, 2008). High expressivity of positive emotions seems to foster resistance against depression. Regarding the expression of negative affect, a moderate amount might be optimal, as too much might indicate low problem solving and coping skills, while too little does not offer the opportunity to learn how others regulate their affect (for a review Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007).

Next to overall emotionality, the extent to which different emotions co-occur between family members, sometimes labeled synchronicity, is a feature of interest. Main, Paxton & Dale (2016) found that high synchronicity of negative affect in a mother – daughter interaction is related to lower discussion satisfaction. Similarly, Hollenstein et al. (2016) investigated simultaneous emotion displays of mothers, fathers, and adolescents in triadic interactions and identified triadic states that are shown more often in depressed families compared to non-depressed families. Such difference in the co-occurrence of affective states between mother, father and adolescent should therefore be taken into account when examining differences between depressed and non-depressed families.

Families may also differ in how family members respond to each other’s affective behavior. Several studies found important differences in how parents react to the children’s display of affect (Schwartz et al., 2012; Sheeber, Hops, Andrews, Alpert, & Davis, 1998), as well as how children react to parental behavior (Davis et al., 1998, 2000). Sadness has been shown to be reinforced if parents react in a facilitative way or diminish their anger display (Schwartz et al., 2012; Sheeber et al., 1998). Likewise, positive feelings of the child are dampened by dysphoric reactions of the parents (Katz et al., 2014; Schwartz et al., 2012). Such patterns are particularly interesting as they resonate with principles of learning theory and could explain why depressed adolescents have problems in maintaining positive emotions (due to the negative reaction) or in downregulating sadness (as it is rewarded by support and anger avoidance).

A dynamic network approach for studying affective family interactions

Numerous studies have investigated affective family interactions using time series data. Typically, most of the studies zoom in on a single aspect of the interaction: frequency and duration of affective behavior (Chaplin, 2006; Sheeber et al., 2009), reactions of children to a specific parental behavior (Davis et al., 1998, 2000), parental reactions to a specific child behavior (Sheeber, Allen, Davis, & Sorensen, 2000; Sheeber et al., 1998), or synchronicity of positive or negative affect between mother and child (Main et al., 2016). The literature has been advanced significantly through the use of these approaches. Recently, however, researchers are also starting to capture the total sum of interactions and processes that take place, by attempting to take into account all affective behaviors at once, and studying how the affective states of the mother-father-adolescent triads change across time. Hollenstein et al. (2016) adapted the state space grid approach (Hollenstein, 2013; Lewis, Lamey, & Douglas, 1999) to identify attractor states (i.e., frequently occurring affective triadic states) that maximally discriminate between depressed and non-depressed families. Additionally, the amount of variability in the affective states is quantified by means of different measures (e.g., dispersion, transitions, predictability; in Hollenstein et al., 2016). While this approach gives an excellent overall summary of the central tendencies and spread of the affective states during interactions, it does not zoom in onto concurrent and sequential linkages between particular behaviors.

In the present study we aim to combine the investigation of overall dynamics with the detailed view on pairwise interactions, by charting (and depicting visually) the frequencies, co-occurrences, and temporal linkages of all the affective behaviors of the three persons involved, in the form of networks. The network approach is increasingly popular in computer sciences, systems biology, and social sciences, but only recently has started gaining ground in the study of psychopathology. In a seminal paper, Borsboom & Cramer (2013) argued that psychopathological syndromes should be conceptualized as a dynamic system of interacting symptoms. The vicious interplay of these symptoms define the psychopathology itself, offering a new perspective on therapy in that clinicians may target influential or central symptoms (i.e., symptoms that activate others once elicited, which allows negativity to spread rapidly through the network). Network analysis is then the perfect tool to shed light on the behavior and characteristics of such dynamic systems, as Barabási said: “Reductionism deconstructed complex systems, bringing us theory of individual nodes and links. Network theory is painstakingly reassembling them, helping us to see the whole again.” (Barabási, 2011, p. 15).

So far, network analysis has been used to study affective dynamics within a single individual (Bringmann et al., 2013, 2016; Pe et al., 2015); in this approach, several emotions are depicted as nodes of the intra-individual affect network, while the temporal sequencing is visualized as links between these nodes (also called edges). This visualization of the network 2 allows one to obtain a complete picture of the interaction between different affective states of an individual. In many cases this visualization generates new questions, as for example, which behaviors play a central role in the interaction (centrality of nodes; Bringmann et al., 2013), which behaviors are related to each other (the density of links; Pe et al., 2015) or what is the overall structure of the network (van Borkulo et al., 2014).

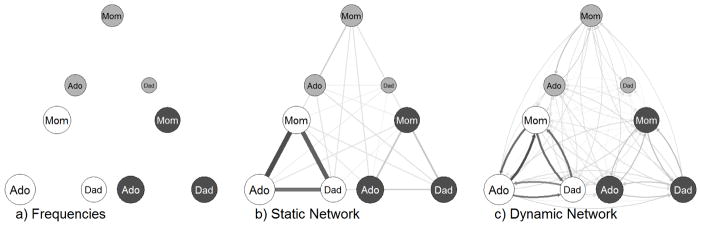

The present paper extends this intra-individual approach to multiple individuals, in this case parents and adolescents. By charting the networks of emotional interaction between different individuals, we can obtain insights in the affective interplay between family members, and how this may differ between depressed and non-depressed families. As we will illustrate by means of Figure 1, showing the average network of the non-depressed families, our network approach also goes beyond existing ones in that it is built to directly represent the three central features of affective family interactions mentioned above. First, we will inspect how frequently different affects are expressed by family members in general. This feature is reflected by the node size in Figure 1. For example, from Figure 1a, we can derive that the fathers of the non-depressed families behave angrily less often than the mothers and adolescents. Second, we will visualize the co-occurrence of affective expressions in static networks and investigate whether they differ between depressed and non-depressed families. For example, in Figure 1b, the thick edges between the happiness nodes of the different actors indicate that happiness co-occurs more frequently between actors than sadness or anger. Finally, we will infer dynamic networks that depict temporally sequenced affective behaviors within and between actors. For instance, the dynamic network (Figure 1c) reveals that adolescent’s happiness is more often followed by mother’s happiness, than the other way around.

Figure 1. Visualization of the expressed affect between family members.

a) frequencies, b) static and c) dynamic network; shading of the nodes: grey= anger; black= dysphoric affect, white= happiness; size of the node represents the relative frequency of a certain affect; thickness and saturation of the links indicate the strength of the tie.

The present study

In the present study, we will reanalyze data from a previous study on affective interactions within families with a depressed adolescent and families with a non-depressed one (Allen et al., 2012; Sheeber et al., 2012). In this study, three family members - mother, father and adolescent – were invited for a lab session. During the session they engaged in three types of family discussions, which were videotaped and coded in one second intervals for the presence and absence of the expressions of angry, dysphoric, and happy affect. Here, we will focus on the problem solving family interactions, which were intended to elicit conflict, as such interactions have been shown to discriminate between families with depressed and those with non-depressed adolescents (Hollenstein et al., 2016; results for the two other types of interaction – event planning and family consensus - can be consulted in the supplementary material). Specifically, we will investigate the frequency of angry, dysphoric, and happy affect, their co-occurrence, and how they affect one another across time. Moreover, as each of the adolescents was either healthy or diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), the data allow the exploration of the extent to which these three interaction features differ between the two subgroups. To this end, we will compare the average network of families with an adolescent that has been diagnosed with MDD with the average network of families with a non-depressed adolescent in order to detect depresso-typic structures.

We expect to find differences between depressed and non-depressed families in overall frequencies of affective expressions (i.e., more anger and dysphoric affect, but less happiness in the depressed families), and this for all family members. For the depressed adolescent, these expectations match the DSM criteria of depressive disorder. We expect similar frequency differences for the parents, because it has been argued that parental behavior plays an important role in learning how to express and regulate emotions (Morris et al., 2007), implying that adolescent’s affective behavior may therefore simply reflect parental behavior. Another theoretical rationale for this hypothesis is the parental meta-emotion philosophy theory (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1996; Katz, Maliken, & Stettler, 2012), which states that parents transfer their ideas about which emotional behavior is appropriate in which situations to their children.

Based on a review of recent findings on the co-occurrence of emotional behaviors in families, Main et al. (2016) conjectured that co-occurrence of positive affect is related to positive developmental outcomes (e.g., secure attachment) while co-occurrence of negative affect points towards negative outcomes (e.g., maladaptive emotion regulation). As these variable relate to depression (Brenning et al., 2012; Joormann & Vanderlind, 2014), we expect to find a strong co-occurrence of happiness in the non-depressed families and a strong co-occurrence of negative affect in the depressed families.

As concerns the temporal dependencies between the emotional expressions of the family members, theories about emotion socialization indicate how parental responses to child’s emotional expression may relate to adolescent depression (Schwartz et al., 2012) through reinforcement and punishment processes. On the basis of this, we hypothesize that dysphoric behavior of the adolescent might be reinforced by increased displays of parental happy behavior in the depressed families or that happy behavior of the adolescent might be dampened by dysphoric or angry parental reactions.

Method

Participants

The Emotion study (Allen et al., 2012; Sheeber et al., 2012) involved 141 adolescents (47 boys, 94 girls), aged 14.5–18.5, and their parents. Adolescents were included, if they met the criteria for either the depressed or the non-depressed group and lived together with at least one parent or permanent guardian. Consistent with the demands of the larger study, adolescents were excluded, if they evidenced comorbid psychotic, externalizing, or substance dependence disorders or if they were taking medication with known cardiac effects, or reported regular nicotine use (Allen et al., 2012).

In this paper, we focused on affective interaction patterns between adolescents and both their parents. Therefore, 46 of the 141 families were excluded because only one parent participated. Another two families were excluded due to technical problems with the video recordings. Hence, the analyses reported here are based on a sample of 93 families, of which the adolescents (aged between 14.5 and 18.5; 57 girls, 36 boys) in 43 families were diagnosed with MDD and in 50 families were healthy controls. Depressed and non-depressed adolescents did not differ significantly with respect to sex, age, or pubertal development.

Recruitment and Assessment Procedure

We briefly describe the recruitment and assessment procedure. More details can be found in Sheeber et al. (2009).

Recruitment Procedure

Adolescents were selected and enrolled using a two-gate recruitment process consisting of a depression screening and a diagnostic interview for the selected adolescents. Adolescents were categorized depressed, if they had elevated scores (>31 for boys and >38 for girls) on the CES-D (depression screener based on self-report; Radloff, 1977) and met the criteria for current MDD during the K-SADS interview (instrument to obtain current and lifetime diagnoses for the adolescent; Orvaschel & Puig-Antich, 1994). Non-depressed adolescents scored below an adolescent appropriate cut off on the CES-D (<21 for boys and <24 for girls) and did not meet the criteria for current or lifetime depressive or other disorders in the subsequent interview.

Lab assessment

Adolescents that met the criteria for inclusion were invited for a lab assessment together with their parents. During this assessment, the adolescents and their parents engaged in six family interactions – two event planning, two family consensus and two problem solving interactions. Each interaction consisted of a 9-min discussion and was video recorded. The affective behavior of both parents and the adolescents during the discussion was coded using the Living in Family Environments coding system (LIFE; Hops, Biglan, Tolman, Arthur, & Longoria, 1995). LIFE is an event-based, micro-analytic coding system, that codes the presence of anger, happiness and dysphoric affect, based on facial expression, voice tone, and body language: Anger is indicated by hostile, harsh, furious, annoyed or irritated behavior (e.g., staccato rhythm, short, clipped speech, tight jaw or clenched teeth, involuntary twitches or jerks or, of course, by direct statement of anger, complaints about the other person, and sharp exhalations). Happiness is coded if the person displays happiness through his/her facial expression, tone of voice or body language. Happiness includes clues like laughter, giggling, bright and beaming positive facial expressions, excited looks that reflect a positive experience or positive energy, speech that is louder than usual, but not angry, exaggerated or animated expressions or gestures, jumping up and down, or clapping hands. Dysphoria represents all sad, blue, unhappy, distressed, withdrawn, depressed, discouraged, downhearted, tearful behavior. Clues for dysphoria are for instance low voice tone, with a slow pace of speech, sighing and yawning, crying, or facial features of dysphoric affect.

For each individual each affective expression was first coded on an event basis (i.e., a coder indicated when a certain affective expression starts and when it is replaced by a different expression; in the coding scheme different affective expressions exclude each other). Next, the codes of all individuals were restructured into second-by-second time series: for each second a code indicated whether a certain behavior was shown or not. The coding procedure results in multivariate binary time series data (i.e., nine variables that indicate the presence/absence of the three affective expressions for the adolescent, mother and father) for each of the six discussions, each consisting of approximately 540 time points. Time points, for which the observation of one or more persons were missing, were deleted. As this happened exclusively in the beginning of the video recording, when the conversation just lifted off, and never exceeded beyond 10 seconds, the impact on the data analysis is negligible. The experienced, extensively trained observers were blind to diagnostic status. About 25% of the videos were coded by two observers, yielding Kappa values between .60 and .64 (Allen et al., 2012), reflecting good reliability.

Results

Affect frequency

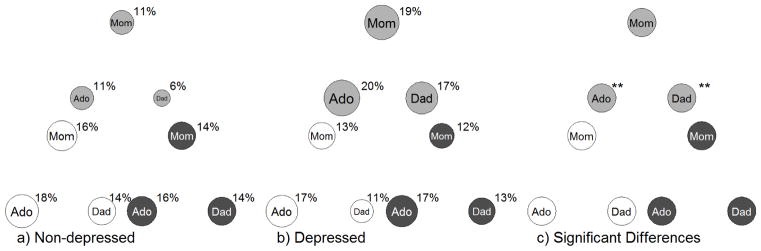

For each family member and each affect, we calculated the relative affect frequency by computing the proportion of time the affect is shown, across the two problem solving interactions. Note that we use relative rather than absolute frequencies to account for the minor differences in the number of coded time points per family. Figure 2 visualizes the average relative affect frequencies for a) the non-depressed and b) the depressed families, by adapting the size of the node to the corresponding average relative affect frequency: the larger the node, the higher the average relative frequency. T-tests (Table 1) confirm the visual impression that anger occurs more frequently for adolescent and father in depressed families than in not-depressed ones, with moderate effect sizes (i.e., Cohen’s d of −.63 and −.68). The relative frequency of the other affects did not differ.

Figure 2. Relative affect frequency.

a) mean relative frequency of non-depressed families b) mean relative frequency of depressed families c) significant differences (**: p<.01, ***p<.001); shading of the nodes: grey= anger; black= dysphoric affect, white= happiness; in a) and b) the size of each node represents the average relative frequency of the corresponding affect.

Table 1.

Differences in relative affect frequency

| Mean (SD) non-depressed |

Mean (SD) depressed |

t | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mom-angry | .113 (.14) | .193 (.17) | −2.51 | .0139* | − .53 |

| Dad-angry | .060 (.10) | .175 (.22) | −3.11 | .0029** | − .68 |

| Ado-angry | .109 (.13) | .203 (.17) | −2.97 | .004** | − .63 |

| Mom-dysphoric | .141 (.15) | .120 (.12) | 0.74 | .4607 | .15 |

| Dad-dysphoric | .145 (.16) | .134 (.12) | 0.38 | .7045 | .08 |

| Ado-dysphoric | .156 (.15) | .170 (.15) | −0.44 | .6627 | − .09 |

| Mom-happy | .159 (.11) | .134 (.09) | 1.23 | .2236 | .25 |

| Dad-happy | .141 (.13) | .107 (.10) | 1.49 | .1400 | .30 |

| Ado-happy | .183 (.12) | .173 (.13) | 0.36 | .7190 | .08 |

Note.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 calculated with t-test assuming unequal variances.

Static network

With the static network we focus on the co-occurrence of affect. To quantify the co-occurrence of two affective responses (referred to as first and second behavior), we computed a static Jaccard similarity (Jaccard, 1912):

where denotes the number of time points that both affective responses are shown at the same moment, the number of time points that only the first affective behavior is shown, and the number of time points that only the second affective behavior is shown. A static Jaccard similarity of ‘1’ is achieved when both affects always co-occur; a score of ‘0’ indicates that they never co-occur.

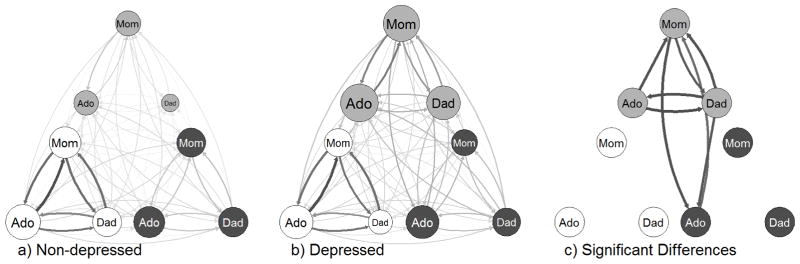

Figure 3 visualizes the static Jaccard similarities by drawing edges between the nodes of Figure 2. Panel a shows the average static Jaccard similarities for the non-depressed families and panel b those for the depressed families. The width of the edges reflects the size of the average similarity indices. Conducting t-tests (assuming unequal variances) on the corresponding edges of both groups of families, revealed four significant differences (p<.01, see Table 2). These differences are plotted in panel c of Figure 3. In this plot, the width of the edges are based on the value of Cohen’s d.

Figure 3. Co-occurrence of affects.

a) mean static Jaccard similarity of non-depressed families b) mean static Jaccard similarity of depressed families c) significant links (p<.01). In c) the linewidth indicates Cohen’s d; shading of the nodes: grey= anger; black= dysphoric affect, white= happiness. In a) and b) the size of the node represents the relative frequency of the corresponding affect.

Table 2.

Differences in co-occurrence of two affective behaviors

| Mean (SD) non-depressed |

Mean (SD) depressed |

t | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ado-angry_Mom-angry | .068(.09) | .131(.13) | −2.69 | .0089** | −.57 |

| Ado-angry_Dad-angry | .030(.05) | .086(.10) | −3.18 | .0023** | −.69 |

| Mom-angry_Dad-angry | .040(.08) | .110(.12) | −3.27 | .0016** | −.70 |

| Ado_dysphoric_Mom_angry | .044(.05) | .081(.08) | −2.61 | .0112* | −.57 |

| Ado_dysphoric_Dad_angry | .024(.04) | .065(.08) | −3.10 | .003** | −.67 |

| Mom_dysphoric_Ado_angry | .033(.04) | .059(.05) | −2.59 | .0112* | −.55 |

Note.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 calculated with t-test assuming unequal variance.

Only links for which p<.05 are listed.

Figure 3 demonstrates that in both groups, happy responses co-occur most frequently. However, the strength of these edges does not differ between depressed and non-depressed families. In contrast, anger is on average displayed more often together in depressed families, for each pair of actors. In addition, dysphoric affect of the adolescent co-occurs more often with angry affect from the father, in depressed families.

Dynamic Network

The dynamic network charts the temporal dependencies between family members’ affective responses. The goal is to investigate how a certain behavior (indicated as first behavior) dynamically impacts another behavior (indicated as second behavior) across a time lag of five seconds, where the two behaviors may stem from the same or from different individuals. The lag of 5 seconds is based on the assumption that the reaction of one partner to the behavior of the other partner takes some time (Allen et al., 2012; Gottman, 2002). However, to be sure that this lag also applies to our data we checked on lags between 1 second and 10 seconds, but did not find differences in significance between the two groups. Taking a smaller interval might cause confusion with the simultaneously occurring emotions, while taking too big an interval increases the risk that behavior is included that does not directly result from the behaviors in question, but is a response to other events. To quantify these temporal relations, we computed a dynamic Jaccard similarity on the lagged data, which indicates how frequently the second behavior is preceded by the first:

where denotes the number of times the first affective behavior is followed five seconds later by the second affective behavior, the number of times the first affect is expressed, but not followed by the second affective behavior five seconds later, and the number of times the second affect is expressed, without being preceded by the first affective behavior five seconds earlier.

Figure 4 visualizes the dynamic Jaccard similarities for all pairs of affect by drawing directed arrows between the nodes. Panel a shows the average values for the non-depressed families and panel b those for the depressed families. We omitted the auto-loops, which chart the carry-over effect of an affective state on itself, as these within-person inertia effects are not the focus of this study and have already been investigated in this sample (Kuppens, Allen, & Sheeber, 2010). Comparing the dynamic Jaccard similarities between the two groups using t-tests assuming unequal variances, revealed 8 edges that are significantly different (p<.01, see Table 3). These differences are plotted in panel c of Figure 4, in which the width of the edges reflects the corresponding value of Cohen’s d.

Figure 4. Affective dynamics (Jaccard similarity index computed on 5s lagged data).

a) mean of non-depressed families b) mean of depressed families c) significant links (p<.01). In c) linewidth indicates Cohen’s d; shading of the nodes: grey= anger; black= dysphoric affect, white= happiness. In a) and b) the size of the node represents the relative frequency of the corresponding affect. Thickness and saturation of the links indicate the strength of the tie. Auto-loops are omitted.

Table 3.

Differences in temporal sequencing of affect (lag 5s)

| Mean (SD) non-depressed |

Mean (SD) depressed |

t | p | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ado-angry_Mom-angry | .064(.09) | .137(.13) | −3.17 | .0022** | −.68 |

| Ado-angry_Dad-angry | .029(.05) | .084(.1) | −3.23 | .0020** | −.70 |

| Mom-angry_Dad-angry | .040(.08) | .106(.12) | −3.06 | .0031** | −.65 |

| Mom-angry_Ado-angry | .069(.09) | .128(.13) | −2.50 | .0148* | −.53 |

| Dad-angry_Ado-angry | .028(.05) | .083(.1) | −3.15 | .0026** | −.69 |

| Dad-angry_Mom-angry | .037(.08) | .104(.12) | −3.17 | .0022** | −.68 |

| Ado-dysphoric_Mom-angry | .044(.05) | .085(.09) | −2.70 | .0090** | −.58 |

| Mom-angry_Ado-dysphoric | .041(.05) | .087(.09) | −3.12 | .0027** | −.68 |

| Ado-dysphoric_Dad-angry | .027(.04) | .062(.08) | −2.64 | .0104* | −.57 |

| Dad-angry_Ado-dysphoric | .025(.04) | .065(.08) | −3.03 | .0036** | −.66 |

| Mom-dysphoric_Ado-angry | .034(.04) | .058(.05) | −2.51 | .0141* | −.53 |

| Ado-angry_Mom-dysphoric | .034(.04) | .056(.05) | −2.37 | .0200* | −.50 |

| Dad-angry_Mom-dysphoric | .026(.05) | .059(.09) | −2.20 | .0317* | −.48 |

| Mom-happy_Ado-angry | .037(.05) | .062(.05) | −2.33 | .0219* | −.49 |

|

|

|||||

| Mom-angry_Mom-angry | .264(.21) | .390(.20) | −2.95 | .0041** | −0.62 |

| Dad-angry_Dad-angry | .212(.18) | .339(.24) | −2.74 | .0076** | −0.60 |

| Ado-angry_Ado-angry | .208(.19) | .343(.20) | −3.30 | .0014** | −0.70 |

Note.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001 calculated with t- test assuming unequal variances.

Only links with differences for which p<.05 are listed. Significant auto-loops are included at the bottom.

In both depressed and non-depressed families, happiness is the most contagious state, in the sense that happiness in one individual is frequently followed by happiness in another individual. Both groups do thus not differ in this respect. However, for anger, the links are significantly stronger in the network of the depressed families. In other words, in depressed families angry behavior by one member is more frequently followed by angry behavior of another family member. Particularly relevant for understanding depressive mood in adolescents, adolescents’ dysphoric behavior and angry behavior of their parents follow upon each other more often in depressed than in non-depressed families.

Discussion

In this paper, we used a novel network approach to explore how affective interactions differ between families with and without a depressed adolescent. Charting and visualizing the average static and dynamic networks for both types of families revealed that in depressed families, anger was expressed more often, co-occurred more frequently between the family members and predicted angry behavior in others more strongly than in non-depressed families. Importantly, dysphoric affect of the adolescent and angry behavior of the parents followed upon each other more often in depressed compared to non-depressed families. Contradictory to what could be expected, no differences in happiness were found.

Happiness

No evidence was found that depressed families show less happiness or interact less happily than non-depressed families during problem solving interactions as neither the relative frequency, nor the co-occurrence measures nor the temporal dependencies differed significantly between the depressed and non-depressed families. These results are not consistent with loss of pleasure or interest being one of the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder (DSM5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This finding may be explained, however, by a discrepancy between experienced and observed happiness. For instance, Chaplin (2006) found that individuals with higher depressive symptoms report less happiness, but do not seem less happy during a stressful interaction. Regarding affect regulation, our results do not support the notion of lower levels of reinforcement of happiness in depressed families (Cole & Rehm, 1986), as parents do not interact less happily with each other or with their depressed child. Likewise, the results yield no evidence of increased parental dampening (Yap et al., 2008) or punishment of happiness, as neither mothers nor fathers displayed more dysphoric or angry responses to adolescent’s happy behavior. A possible explanation is that such mechanisms supporting or undermining happiness have been observed in studies with younger children (Cole & Rehm: 8–12y; Yap et al.: 11–13y), but are not always found in those with older ones (e.g., Chaplin, 2006). Main et al. (2016) also pointed out that the problem solving task might not elicit differences in happiness between families, due to its focus on conflict resolution. However, although happiness is more often shown in the event planning tasks (see supplementary material), even in these tasks, neither frequency nor links between happiness nodes differed significantly between the two types of families.

Dysphoria

The frequency of dysphoric affect does not differ significantly between the depressed and non-depressed families. The same holds for the co-occurrence of dysphoric affect and the temporal dependencies involving only dysphoria. These results are remarkable, as they are not in line with commonly used diagnostic procedures that consider dysphoric affect as a key diagnostic symptom of depression (indeed, the adolescents designated as depressed in this study would have had to endorse this symptom to be included in the depressed group). Note that Sheeber et al. (2012) also reported that the depressed group examined in the current study did demonstrate higher baseline levels of dysphoric affect. As the latter used micro-coded data from a mix of different tasks (i.e., a problem solving and a family consensus task, compared to just examining the problem solving tasks as we did here), contextual aspects of these different tasks might explain at least part of the difference in findings. More precisely, the problem solving interaction task seems to elicit conflict and therefore angry behavior, but not dysphoric behavior (Sheeber et al., 2012). Indeed, during the family consensus tasks (see supplementary material), all three family members show more dysphoric behavior than during the problem solving task, nevertheless, the differences between the two types of families (non-depressed vs. depressed) are not significant for any of the three features in these family consensus tasks.

Anger

Anger was expressed more frequently in the families with depressed adolescents than in the non-depressed families, and these expressions of anger were also shown more often contemporaneously or following expression of anger of another person. However, a leader-follower pattern - in the sense that anger of one family member did more often follow or lead the anger of another family member- did not emerge.

These findings are in line with results of previous research. Depressed adolescents showed more anger and irritability than do non-depressed adolescents (Ingram, Trenary, Odom, Berry, & Nelson, 2007; Sheeber et al., 2009; Wenze, Gunthert, & Forand, 2007). With regard to the co-occurrence of anger, higher simultaneous expression of negative affect was found by Main et al. (2016) for low satisfied mother-adolescent dyads. Finally, with respect to the temporal dependencies, Schwartz et al. (2012) found that reciprocation of adolescent’s anger was related to depression. Overall, our findings are consistent with previous evidence that depressed adolescents experience harsher and more conflictual interactions with both of their parents than do non-depressed adolescents (Sheeber, et al., 2007).

Combining the findings of higher frequency, co-occurrence, and temporal sequencing of anger between family members in depressed relative to control families, these findings paint a picture of the depressed family becoming stuck in a cycle of angry affectivity. As such, our findings seem to extend earlier results on intra-individual affect dynamics that showed that depressed individuals tend to perseverate longer in specific negative affective states (inertia; Kuppens et al., 2010), and are more predictable and less flexible in moving from one negative affect to another (higher density of negative emotions in affect network; Pe et al., 2015). In this problem solving family interaction, anger regulation strategies seem to fall short for all three family members (on average, at least), as the elevated irritability found is not only shown by the depressed person (i.e., the adolescent), but characterizes also the behavior of the parents. It is not unlikely that intergenerational transmission of maladaptive affect regulation could explain part of this findings (Buckholdt, Parra, & Jobe-Shields, 2014). For this reason, interventions that address only child factors of adolescent depression, while not addressing the problematic functioning of the parents at the same time, might fall short (Kazdin & Weisz, 1998). Thus, our findings point into the same direction as Restifo & Bögels (2009), who indicate that “communication”, “problem solving” and “parent-youth conflict” are among the most important elements that family-based therapy should target.

Inter-affect dynamics

Several links between anger and dysphoric affect are stronger in the depressed families when compared with the non-depressed families: next to a concurrent link between paternal anger and adolescent’s dysphoric behavior, maternal anger and adolescent’s dysphoric affect reciprocate each other and paternal anger is followed by adolescents’ dysphoric affect but not vice versa. Normally, adolescence is a period of highly flexible behavior as adolescents abandon familiar child behavior patterns and experiment with new behaviors (Granic et al., 2003). The temporal dependencies between anger and dysphoria, reinforces the impression that the interaction between mother, father and adolescent gets stuck in negativity (see above), rather than engaging in a healthy exploration of other ways of dealing with negative affect.

Implications for clinical practice

The novel network approach used in the present study reveals how affective interaction patterns differ between depressed and non-depressed families. The results inform clinical practice by suggesting that family-based intervention may be helpful when treating adolescent depression, as this allows one to address parental factors as well as child factors and to strengthen or build adaptive affective interaction patterns between parents and adolescents.

Though this study concentrated on the differences between the two subgroups - depressed vs. non-depressed, the pattern of behavior observed in each triad varied considerably. On the one hand, this may call for further refinement to be accomplished by looking at heterogeneity of family interactions within subgroups, especially, given the symptomatic heterogeneity in the presentation of depression (Fried & Nesse, 2015). Therefore, it may be advisable to cluster families within diagnostic groups (Bulteel, Tuerlinckx, Brose, & Ceulemans, 2016a), or take into account covariates (e.g., family characteristics). On the other hand, in clinical practice, it may point towards studying family-specific networks. The three panels in Figure 5, for example, depict the interaction of three different depressed families in our sample. Each family shows a somewhat different picture: While in the first family (Figure 5a), the adolescent and mother strongly follow each other in anger and dysphoric affect; in the second family (Figure 5b), father’s anger seems to play a central role. For the third family (Figure 5c), mother’s anger is connected with both adolescent’s anger and dysphoria, while neither mother’s nor father’s happiness is adopted by the adolescent. Such individual networks are promising for differential diagnostics (Wigman et al., 2015) or for tailored personalized intervention approaches (Fried et al., 2017; van Roekel et al., 2016).

Figure 5. Affective dynamics (Jaccard similarity index computed on 5s lagged data) in different families with a depressed adolescent.

a) Family 1 b) Family 2 c) Family 3; shading of the nodes: grey= anger; black= dysphoric affect, white= happiness. The size of the node represents the relative frequency of the corresponding affect. Thickness and saturation of the links indicate the strength of the tie. Auto-loops are omitted.

Theoretical implications

In this paper, we addressed onset and maintenance of adolescent depression theoretically and methodologically from two different viewpoints. On the one hand, family systems theory conceptualizes the depressive symptoms of the individual as a problem of the whole family, which is clearly visible in the interplay of the whole family unit (e.g., communication patterns in real time), and therefore aims to understand the complex family dynamics. On the other hand, developmental psychopathology focuses on the individual’s development over time, taking into account how context and previous experiences shaped the individual. These two approaches do not necessarily exclude each other: Davies and Cicchetti (2004), for example, argued that much could be gained by combining the two frameworks. Family systems theory could improve the understanding of the family dynamics by examining how they impact the individual, while developmental psychopathology would get a deeper understanding of the individual’s development by considering the related family processes. The method we used in this study is able to bridge the gap between the two approaches as it allows to quantify and depict the complexity of the family system in a rigorous way and relate it to developmental outcomes. We showed that the average affective interaction patterns in families differ considerably depending on whether the adolescent is depressed or not. This method provides empirical researchers with a new tool in hand to operationalize and translate theoretical concepts (such as emotional learning, meta-emotional philosophy, …) into quantifiable network features.

Future directions for the network approach

Future research could extended this approach in several ways. First, in this study, we investigated all pairwise interactions between mother, father, and adolescent. An important next step is to consider the combined influence of two persons on the third one at the next time point. Is it, for example, necessary that both parents are angry, for the adolescent to become angry, or is it sufficient that one parent is angry? Or can anger of the mother be counteracted by simultaneous happiness from the father? Such questions can be addressed by constructing networks based on Boolean (e.g., Aldana, Coppersmith, & Kadanoff, 2003; Kauffman, 1969) or logistic (e.g., Lumino, Ragozini, Duijn, & Vitale, 2016; Schumacher, Roßner, & Vach, 1996; van Borkulo et al., 2014) regression models, although one should be cautious when interpreting regression weights as they only reveal unique direct effects ignoring shared dynamics (Bulteel, Tuerlinckx, Brose, & Ceulemans, 2016b).

Second, we have focused on sequential dependencies between two behaviors, so far. However, influential parenting theories have elaborated more complex patterns and behavioral cycles, for example, coercive processes by Patterson (1982; for a review, Scaramella & Leve, 2004). Adapting the network approach to unravel such multi-step behavioral sequences, might bring important new insights in maladaptive interaction processes between parents and adolescents and how they relate to depression.

Third, we calculated all networks over the entire course of the interaction. However, it is very likely, that an interaction consists of meaningful phases, e.g., getting angry and start to quarrel, but also of transition phases where not much is going on. Calculating a network for the entire interaction, might obscure the characteristics of the maladaptive phases. A possible way out is to isolate these meaningful phases with change point detection methods (e.g., Cabrieto, Tuerlinckx, Kuppens, Grassmann, & Ceulemans, 2017) and to draw networks for different episodes during the conversation.

Conclusion

In this study a network approach was used to depict: 1) the frequencies of different affects; 2) concurrent expressions of affect; and 3) the temporal relationship between affective behaviors among family members of depressed or non-depressed adolescents during problem solving interactions. Results show that families of depressed adolescents express more anger than families with a non-depressed adolescent. These expressions of anger co – occur and interact more often in families with a depressed adolescent than in the other families, potentially creating a more self-sustaining network of angry negative affect in depressed families. Moreover, parental angry behavior and adolescents’ dysphoric affect follow upon each other more often in the depressed families. Taken together, these patterns reveal a particular family dynamic that may contribute to the adolescents’ depressed mood. Using a network approach to visualize affective interaction patterns might help us, in the long run, to understand adolescent depression and illuminate the road towards effective strategies of treatment or prevention of adolescent depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research leading to the results reported in this paper was sponsored in part by a research grant from the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO, Project No. G066316N awarded to Eva Ceulemans and Francis Tuerlinckx), by the Belgian Federal Science Policy within the framework of the Interuniversity Attraction Poles program (IAP/P7/06), and by the Research Council of KU Leuven (GOA/15/003). Data collection was funded by the US National Institute of Mental Health (grant number MH065340).

Footnotes

For reasons of parsimony, we will call the families with a depressed adolescent simply depressed families. Correspondingly, families in which the adolescents are free of MDD will be called non-depressed families.

All network figures in this paper are plotted with the R package qgraph (Epskamp, Cramer, Waldorp, Schmittmann, & Borsboom, 2012).

Contributor Information

Nadja Bodner, KU Leuven (University of Leuven), Belgium.

Peter Kuppens, KU Leuven (University of Leuven), Belgium.

Nicholas B. Allen, University of Oregon, United States

Lisa B. Sheeber, Oregon Research Institute, United States

Eva Ceulemans, KU Leuven (University of Leuven), Belgium.

References

- Aldana M, Coppersmith S, Kadanoff LP. Boolean Dynamics with Random Couplings. In: Kaplan E, Marsden JE, Sreenivasan KR, editors. Perspectives and Problems in Nolinear Science. Springer; New York: 2003. pp. 23–89. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NB, Kuppens P, Sheeber LB. Heart rate responses to parental behavior in depressed adolescents. Biological Psychology. 2012;90(1):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NB, Sheeber LB, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- Allen NB, Sheeber LB. The importance of affective development for the emergence of depressive disorders during adolescence. In: Allen NB, Sheeber LB, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008b. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barabási AL. The network takeover. Nature Physics. 2011;8(1):14–16. doi: 10.1038/nphys2188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TR. Children of affectively ill parents: a review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(11):1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Williamson DE, Brent DA, Kaufman J, Dahl RE, … Nelson BR. Childhood and Adolescent Depression: A Review of the Past 10 Years. Part I. Journal of the American Academy of Child. 1996;35(11):1427–1439. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore S-J. Imaging brain development: The adolescent brain. NeuroImage. 2012;61(2):397–406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network Analysis: An Integrative Approach to the Structure of Psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9(1):91–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenning K, Soenens B, Braet C, Bosmans G. Attachment and depressive symptoms in middle childhood and early adolescence: Testing the validity of the emotion regulation model of attachment. Personal Relationships. 2012;19(3):445–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01372.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann LF, Pe ML, Vissers N, Ceulemans E, Borsboom D, Vanpaemel W, … Kuppens P. Assessing Temporal Emotion Dynamics Using Networks. Assessment. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1073191116645909. 1073191116645909. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bringmann LF, Vissers N, Wichers M, Geschwind N, Kuppens P, Peeters F, … Tuerlinckx F. A Network Approach to Psychopathology: New Insights into Clinical Longitudinal Data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(4):e60188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumariu LE, Kerns KA. Parent–child attachment and internalizing symptoms in childhood and adolescence: A review of empirical findings and future directions. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22(1):177–203. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckholdt KE, Parra GR, Jobe-Shields L. Intergenerational Transmission of Emotion Dysregulation Through Parental Invalidation of Emotions: Implications for Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23(2):324–332. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9768-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulteel K, Tuerlinckx F, Brose A, Ceulemans E. Clustering Vector Autoregressive Models: Capturing Qualitative Differences in Within-Person Dynamics. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016a:7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bulteel K, Tuerlinckx F, Brose A, Ceulemans E. Using Raw VAR Regression Coefficients to Build Networks can be Misleading. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2016b;51(2–3):330–344. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2016.1150151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrieto J, Tuerlinckx F, Kuppens P, Grassmann M, Ceulemans E. Detecting correlation changes in multivariate time series: A comparison of four non-parametric change point detection methods. Behavior Research Methods. 2017;49(3):988–1005. doi: 10.3758/s13428-016-0754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM. Anger, Happiness, and Sadness: Associations with Depressive Symptoms in Late Adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(6):977–986. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9033-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth S. The Development of Depression in Children and Adolescents. American Psychologist. 1998;53(2):221–241. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Rehm LP. Family Interaction Patterns and Childhood Depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14(2):297–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00915448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies P, Campbell SB. Developmental psychopathology and family process: theory, research, and clinical implications. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. Adolescent Brain Development: A Period of Vulnerabilities and Opportunities. Keynote Address. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021(1):1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cicchetti D. Toward an integration of family systems and developmental psychopathology approaches. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16(3):477–481. doi: 10.1017/S0954579404004626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116(3):387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Hops H, Alpert A, Sheeber LB. Child responses to parental conflict and their effect on adjustment: a study of triadic relations. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12(2):163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Sheeber L, Hops H, Tildesley E. Adolescent Responses to Depressive Parental Behaviors in Problem-Solving Interactions: Implications for Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(5):451–465. doi: 10.1023/A:1005183622729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRose L, Brooks-Gunn J. Pubertal development in early adolescence: implications for affective processes. In: Allen NB, Sheeber LB, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin A, Santens T, Braet C, De Raedt R, Vos P, Maes B, Bosmans G. Middle Childhood Support-Seeking Behavior During Stress: Links With Self-Reported Attachment and Future Depressive Symptoms. Child Development. 2016;87(1):326–340. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012;48(4):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fried EI, van Borkulo CD, Cramer AOJ, Boschloo L, Schoevers RA, Borsboom D. Mental disorders as networks of problems: a review of recent insights. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2017;52(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1319-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried EI, Nesse RM. Depression is not a consistent syndrome: An investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR*D study. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;172:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde PF. The interpersonal structure of family interaction settings: Parent–adolescent relations in dyads and triads. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(3):297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, editor. The mathematics of marriage: dynamic nonlinear models. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Parental Meta-Emotion Philosophy and the Emotional Life of Families: Theoretical Models and Preliminary Data. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10(3):243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Hollenstein T, Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. Longitudinal analysis of flexibility and reorganization in early adolescence: A dynamic systems study of family interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(3):606–617. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haefner J. An Application of Bowen Family Systems Theory. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2014;35(11):835–841. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2014.921257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaker EL, Ceulemans E, Grasman RPPP, Tuerlinckx F. Modeling Affect Dynamics: State of the Art and Future Challenges. Emotion Review. 2015;7(4):316–322. doi: 10.1177/1754073915590619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T. State space grids: Analyzing dynamics across development. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31(4):384–396. doi: 10.1177/0165025407077765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T. State space grids: depicting dynamics across development. New York: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenstein T, Allen NB, Sheeber L. Affective patterns in triadic family interactions: Associations with adolescent depression. Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28(01):85–96. doi: 10.1017/S0954579415000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Biglan A, Tolman A, Arthur J, Longoria N. Living in Family Environments (LIFE) coding system: (Reference manual for coders) Eugene, OR: Oregon Research Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter EC, Hessler DM, Fainsilber Katz L. Familial processes related to affective development. In: Allen NB, Sheeber L, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 262–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Trenary L, Odom M, Berry L, Nelson T. Cognitive, affective and social mechanisms in depression risk: Cognition, hostility, and coping style. Cognition and Emotion. 2007;21(1):78–94. doi: 10.1080/02699930600950778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard P. The Distribution of the Flora in the Alpine Zone. New Phytologist. 1912;11(2):37–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1912.tb05611.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Vanderlind WM. Emotion Regulation in Depression The Role of Biased Cognition and Reduced Cognitive Control. Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2(4):402–421. doi: 10.1177/2167702614536163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Maliken AC, Stettler NM. Parental Meta-Emotion Philosophy: A Review of Research and Theoretical Framework. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(4):417–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00244.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz LF, Shortt JW, Allen NB, Davis B, Hunter E, Leve C, Sheeber L. Parental Emotion Socialization in Clinically Depressed Adolescents: Enhancing and Dampening Positive Affect. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2014;42(2):205–215. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9784-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman SA. Metabolic stability and epigenesis in randomly constructed genetic nets. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1969;22(3):437–467. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(69)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Weisz JR. Identifying and developing empirically supported child and adolescent treatments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(1):19–36. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesek A, Zelazo PD, Lewis MD. The development of executive cognitvie function and emotion regulation in adolescence. In: Allen NB, Sheeber LB, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kuppens P, Allen NB, Sheeber LB. Emotional Inertia and Psychological Maladjustment. Psychological Science. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0956797610372634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Seeley JR, Rohde P. Major Depression in Community Adolescents: Age at Onset, Episode Duration, and Time to Recurrence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33(6):809–818. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Natural Course of Adolescent Major Depressive Disorder: I. Continuity Into Young Adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38(1):56–63. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Lamey AV, Douglas L. A new dynamic systems method for the analysis of early socioemotional development. Developmental Science. 1999;2(4):457–475. doi: 10.1111/1467-7687.00090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, Kunnen SE, van Geert PLC. Here we go again: A dynamic systems perspective on emotional rigidity across parent–adolescent conflicts. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1364–1375. doi: 10.1037/a0016713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipps G, Lowe GA, Gibson RC, Halliday S, Morris A, Clarke N, Wilson RN. Parenting and depressive symptoms among adolescents in four Caribbean societies. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2012;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loon LMAV, de Ven MOMV, Doesum KTMV, Witteman CLM, Hosman CMH. The Relation Between Parental Mental Illness and Adolescent Mental Health: The Role of Family Factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2014;23(7):1201–1214. doi: 10.1007/s10826-013-9781-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lumino R, Ragozini G, van Duijn M, Vitale MP. A mixed-methods approach for analysing social support and social anchorage of single mothers’ personal networks. Quality & Quantity. 2016:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s11135-016-0439-6. [DOI]

- Main A, Paxton A, Dale R. An Exploratory Analysis of Emotion Dynamics Between Mothers and Adolescents During Conflict Discussions. Emotion. 2016;16(6):913–928. doi: 10.1037/emo0000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky A, Schlechter M, Netter S, Keehn D. Maternal and Paternal Parenting Styles in Adolescents: Associations with Self-Esteem, Depression and Life-Satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(1):39–47. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9066-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S. Families & family therapy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, Robinson LR. The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Social Development (Oxford, England) 2007;16(2):361–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-epidemiologic version-5 (KSADS- E-5) Ft. Lauderdale, FL: Nova Southeastern University; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson B. Emotions are social. British Journal of Psychology. 1996;87(4):663–683. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1996.tb02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. Coercive family process. Vol. 3. Eugene, Oregon: Castalia Publishing Company; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pe ML, Kircanski K, Thompson RJ, Bringmann LF, Tuerlinckx F, Mestdagh M, … Gotlib IH. Emotion-Network Density in Major Depressive Disorder. Clinical Psychological Science. 2015;3(2):292–300. doi: 10.1177/2167702614540645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey MA, Gentzler AL. An upward spiral: Bidirectional associations between positive affect and positive aspects of close relationships across the life span. Developmental Review. 2015;36:58–104. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2015.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Restifo K, Bögels S. Family processes in the development of youth depression: Translating the evidence to treatment. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(4):294–316. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Leve LD. Clarifying Parent–Child Reciprocities During Early Childhood: The Early Childhood Coercion Model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7(2):89–107. doi: 10.1023/B:CCFP.0000030287.13160.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M, Roßner R, Vach W. Neural networks and logistic regression: Part I. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 1996;21(6):661–682. doi: 10.1016/0167-9473(95)00032-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz OS, Sheeber LB, Dudgeon P, Allen NB. Emotion socialization within the family environment and adolescent depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2012;32(6):447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz OS, Simmons JG, Whittle S, Byrne ML, Yap MBH, Sheeber LB, Allen NB. Affective Parenting Behaviors, Adolescent Depression, and Brain Development: A Review of Findings From the Orygen Adolescent Development Study. Child Development Perspectives. 2017;11(2):90–96. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Epidemiology of mood disorders during adolescence: implications for lifetime risk. In: Allen NB, Sheeber LB, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Allen NB, Leve C, Davis B, Shortt JW, Katz LF. Dynamics of affective experience and behavior in depressed adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(11):1419–1427. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Allen N, Davis B, Sorensen E. Regulation of Negative Affect During Mother–Child Problem-Solving Interactions: Adolescent Depressive Status and Family Processes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28(5):467–479. doi: 10.1023/A:1005135706799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Davis B, Leve C, Hops H, Tildesley E. Adolescents’ Relationships with Their Mothers and Fathers: Associations with Depressive Disorder and Subdiagnostic Symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(1):144–154. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Hops H, Andrews J, Alpert T, Davis B. Interactional processes in families with depressed and non-depressed adolescents: Reinforcement of depressive behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36(4):417–427. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Kuppens P, Shortt JW, Katz LF, Davis B, Allen NB. Depression is associated with the escalation of adolescents’ dysphoric behavior during interactions with parents. Emotion. 2012;12(5):913–918. doi: 10.1037/a0025784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9(2):69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MC, McKowen JW, Rosenbaum Asarnow J. Adolescent mood disorders and familial processes. In: Allen NB, Sheeber LB, editors. Adolescent emotional development and the emergence of depressive disorders. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. pp. 280–297. [Google Scholar]

- van Borkulo CD, Borsboom D, Epskamp S, Blanken TF, Boschloo L, Schoevers RA, Waldorp LJ. A new method for constructing networks from binary data. Scientific Reports. 2014:4. doi: 10.1038/srep05918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Van Kleef GA, De Dreu CKW, Manstead ASR. An Interpersonal Approach to Emotion in Social Decision Making. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2010;42:45–96. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(10)42002-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Roekel E, Masselink M, Vrijen C, Heininga VE, Bak T, Nederhof E, Oldehinkel AJ. Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial to explore the effects of personalized lifestyle advices and tandem skydives on pleasure in anhedonic young adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0880-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verboom CE, Sijtsema JJ, Verhulst FC, Penninx BWJH, Ormel J. Longitudinal associations between depressive problems, academic performance, and social functioning in adolescent boys and girls. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(1):247–257. doi: 10.1037/a0032547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls TA, Schafer JL. Models for Intensive Longitudinal Data. Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wenze SJ, Gunthert KC, Forand NR. Influence of dysphoria on positive and negative cognitive reactivity to daily mood fluctuations. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(5):915–927. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner-Seidler A, Banks R, Dunn BD, Moulds ML. An investigation of the relationship between positive affect regulation and depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2013;51(1):46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigman JTW, van Os J, Borsboom D, Wardenaar KJ, Epskamp S, Klippel A, Wichers Exploring the underlying structure of mental disorders: cross-diagnostic differences and similarities from a network perspective using both a top-down and a bottom-up approach. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(11):2375–2387. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap MBH, Allen NB, Ladouceur CD. Maternal Socialization of Positive Affect: The Impact of Invalidation on Adolescent Emotion Regulation and Depressive Symptomatology. Child Development. 2008;79(5):1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.