Abstract

Objective(s):

Calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) receptors are widely distributed in the central nervous system. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of CGRP on pain behavioral responses and on levels of monoamines in the periaqueductal gray area (PAG) during the formalin test in rats.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty-four male rats were studied in four groups (n=6). CGRP was injected into the left cerebral ventricle (1.5 nmol, 5 µl). After 20 min, formalin (2.5%) was subcutaneously injected into the right hind paw. Behavior nociceptive score was recorded up to 60 min. During the formalin test, the PAG was subjected to microdialysis and levels of norepinephrine, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl-glycol (HMPG), dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC), serotonin and 5-hydroxyindole-acetic acid (HIAA) were measured by HPLC.

Results:

ICV injection of CGRP lead to a significant pain reduction in acute, middle and chronic phases of the formalin test. Dialysate concentrations of norepinephrine, HMPG, dopamine, DOPAC, serotonin and HIAA in the PGA area showed an increase in acute phase, middle phase and beginning of the chronic phase of the formalin test.

Conclusion:

CGRP significantly reduced pain by increased concentrations of monoamines and their metabolites in dialysates from PAG when injected ICV to rats.

Keywords: CGRP, Formalin test, HPLC, Monoamines, Microdialysis, Periaqueductal gray area

Introduction

The nucleus of periaqueductal grey (PAG) and nucleus of raphe magnus (NRM) have the most important role in pain modulation (1). Neurons located in NRM and nucleus reticularis gigantocellularis that are within the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) are projected to spinal dorsal horn and affect pain nociception (2). In descending pain control pathways many neurotransmitters and neuropeptides are involved (3).

Norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin are the most important neurotransmitters involved in analgesic system (4). Periaqueductal gray area receives monoaminergic innervation from different areas of the brain (5).

Calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) has many biological functions, including pain sensation (6, 7). CGRP and its receptors have been widely distributed in the brain (8). CGRP receptors have significant concentrations in periacueductal grey, nucleus raphe obscurus, nucleus raphe palidus, nucleus raphe magnus and subset of neurons in dorsal root ganglia (8-12). CGRP has a role in antinociception systems in PAG and trigeminocervical complex (13-15). ICV administration of low doses of CGRP has an analgesic effect in tail flick test, while high doses have shown antinociceptive effects in hot plate test (16, 17).

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of ICV injection of CGRP on behavioral responses and monoamines level changes in the periaqueductal gray in formalin test.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Veterinary Medicine of Shiraz University.

Twenty-four male Sprague Dawley rats (270±30 g) were used. Food and water were freely available and the animals were kept at 22 ± 2°C and 12 hr dark/light cycle.

Experimental groups

The rats were divided into four groups (n=6). In the first group artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) was ICV injected (5 µl) and normal saline was injected subcutaneously (SC) in the hind paw (50 µl). In the second group ACSF was ICV injected (5 µl) and formalin 2.5% was injected SC in the hind paw (50 µl). In the third group CGRP with a dose of 1.5 nmol was ICV injected (5 µl) and normal saline was injected SC in the hind paw (50 µl). In the fourth group CGRP with a dose of 1.5 nmol was ICV injected (5 µl) and formalin 2.5% was injected SC in the hind paw (50 µl).

Surgery and probe implantation

The rats were anesthetized by sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) intraperitoneally. The guide cannula was implanted in the brain ventricle with coordinates (AP: -0.8, L: +1.5, DV: -3.5). Microdialysis probes with an active dialysis length of 1 mm were constructed in our laboratory from cellulose dialysis tubing. The probes were tested in vitro to determine the relative recovery of monoamines and their metabolites. Microdialysis probe was implanted into the PAG with coordinates (AP: -7.6, L:0.6, DV: -5.8) (18).

Nociceptive score and microdialysis

Formalin test was done and nociceptive score was recorded: if the animal does not indicate any certain behavior, number zero, if the animal’s feet are on the ground and it does not put pressure on it, number one, if the animal hits the ground with its feet or accumulates its legs in the abdomen, number two, and finally if the animal licked/bit the injected paw, number three was given (19). Subcutaneous injection of formalin in the hind paw creates a biphasic response. The first 5 min after injection is the acute phase. Chronic phase is from the end of 15 min until the end of 60 min. Also, the middle phase is considered from the end of 5 min until the end of 15 min (20).

After 24 hr the animals were placed within a polycarbonate chamber and they were allowed to adapt for 15 min. The ICV injection was performed by the Hamilton syringe 5µl within one min (rat CGRP was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich). Formalin test was performed after the optimum time for the effect of the drugs (20 min). Microdialysis Probes were perfused with ACSF at a flow rate of 2.0 µl/min (WPI, SP 210, syringe pump) and 30 µl fractions were collected every 15 min. From the beginning until the end of the experiment, eight microdialysis samples were collected, respectively. [Base sample without medication effect (S1), Base sample with medication effect (S2), four samples related to different times of the formalin test (S3-S6) and two samples after completion of formalin test (S7, S8)]. The composition of ACSF was (in mM): NaCl 114, CaCl2 1, KCl 3, MgSO4 2, NaH2PO4 1.25, NaHCO3 26, NaOH 1, glucose 10, and pH=7.4.

Chemical assays

In order to measure norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and their metabolites in the dialysis samples (n=6), high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection (ECD) was used. After adding the internal standard (14.3 µl) samples were injected into the column (Revers-phase column Eurospher 100-5 C18, 250×4.6 mm), pump (Knauer) and electrochemical detector (Amperometric detector EC 3000). The oxidizing potential of the ECD cell was 750 mV. A. The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of sodium phosphate 8.4 g, 1-octane-sulfonic acid 360 mg, EDTA 30 mg and 16% methanol in 1000 ml HPLC grade water (pH=4.5). The flow rate of mobile phase was 1.0 ml/min.

Histological verification

At the end of formalin test, the animals were euthanized with an overdose of diethyl ether. Then, the animals’ brains were taken out and were placed in formalin 10%. After a few days the brains were cut and the place of guide cannula in ventricle and microdialysis probe in periaqueductal gray area in all animals were confirmed based on Paxinos (18).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by using SPSS software with statistical method of the one-way ANOVA for assessing the groups and Duncan’s tests as post-hoc were performed. The significance level was considered P<0.05.

Results

Formalin test

The results of pain-related behaviors at different phases of the formalin test are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Pain-related behaviors at different phases in formalin test. Dissimilar letters indicate significant difference between groups (a, b, c, d)

| Phases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Acute phase | Inter phase | Chronic phase |

| 1 | 0.13±0.05a | 0±0a | 0±0a |

| 2 | 2.4±0.05d | 1.92±0.03c | 2.05±0.01c |

| 3 | 0.1±0.05a | 0±0a | 0±0a |

| 4 | 1.46±0.08c | 0.35±0.06b | 1.87±0.03b |

ICV injection of CGRP in the fourth group significantly decreased nociceptor score in acute phase of the formalin test compared with the second group (P<0.05) (Figure 1). CGRP in the middle phase and the chronic phase of the formalin test of the fourth group significantly reduced nociceptive score compared with the second group (P<0.05) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The nociceptive score in different groups. (Group 1: ACSF was ICV injected and normal saline was injected subcutaneously (SC) in the hind paw. Group 2: ACSF was ICV injected and formalin 2.5% was injected SC. Group 3: CGRP with a dose of 1.5 nmol was ICV injected and normal saline was injected SC. Group 4: CGRP with a dose of 1.5 nmol was ICV injected and formalin 2.5% was injected SC)

* Significant differences between group 2 and group 4 (P<0.05)

Microdialysis

Third samples (S3) of microdialysis are related to acute and middle phases of the formalin test that contain aCSF collected from PAG in time points of 0-15 min in the formalin test. Fourth, fifth and sixth samples (S4- S6) are related to the chronic phase of the formalin test which have been collected within times of 15-30, 30-45 and 45-60 min in the formalin test.

Norepinephrine

In groups 1 and 3 no significant differences were seen in norepinephrine concentrations at any of the time points. Norepinephrine concentration within 0-15 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. Norepinephrine concentration within 15-30 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was higher than that of the second group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concentrations of norepinephrine in different groups. (Group 1: ACSF was ICV injected and normal saline was injected subcutaneously (SC) in the hind paw. Group 2: ACSF was ICV injected and formalin 2.5% was injected SC. Group 3: CGRP with a dose of 1.5 nmol was ICV injected and normal saline was injected SC. Group 4: CGRP with a dose of 1.5 nmol was ICV injected and formalin 2.5% was injected SC). [Base sample without medication effect (S1), Base sample with medication effect (S2), four samples related to different times of the formalin test (S3-S6) and two samples after completion of formalin test (S7, S8)].

* Significant differences between group 2 and group 4 (P<0.05)

HMPG

In groups 1 and 3 no significant differences were seen in HMPG concentrations at any time points. HMPG concentration within 0-15 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. HMPG concentration within 15-30 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was higher than that of the second group. HMPG concentration within 30-45 and 45-60 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was higher than that of the second group, but the difference was not significant (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of HMPG in different groups. [Base sample without medication effect (S1), Base sample with medication effect (S2), four samples related to different times of the formalin test (S3-S6) and two samples after completion of formalin test (S7, S8)]

* Significant differences between group 2 and group 4 (P<0.05)

Dopamine

In groups 1 and 3 no significant differences were seen in dopamine concentrations at any of the tested times.

Dopamine concentration within 0-15 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. Dopamine concentration within 15-30 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was higher than that of the second group. Dopamine concentration within 30-45 and 45-60 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was higher than that of the second group, but the difference was not significant (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

concentration of dopamine in test and control groups. [Base sample without medication effect (S1), Base sample with medication effect (S2), four samples related to different times of the formalin test (S3-S6) and two samples after completion of formalin test (S7, S8)]

* Significant differences between group 2 and group 4 (P<0.05)

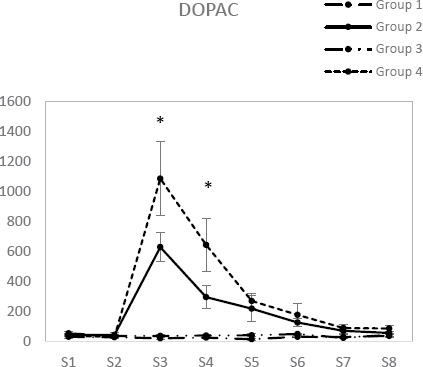

DOPAC

In groups 1 and 3 no significant differences were seen in DOPAC concentrations any of the time points. DOPAC concentration within 0-15 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. Dopamine concentration within 15-30 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was higher than that of the second group. DOPAC concentration within 30-45 and 45-60 min after formalin injection in the fourth group compared with second group showed no significant difference (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Concentration of DOPAC in test and control groups. [Base sample without medication effect (S1), Base sample with medication effect (S2), four samples related to different times of the formalin test (S3-S6) and two samples after completion of formalin test (S7, S8)]

* Significant differences between group 2 and group 4 (P<0.05)

Serotonin

In groups 1 and 3 no significant differences were seen in serotonin concentrations at any of the tested times. Serotonin concentration within 0-15 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. Serotonin concentration within 15-30 and 30-45 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. Serotonin concentration within 45-60 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was higher than that of the second group, but the difference was not significant (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Concentrations of serotonin in different groups. [Base sample without medication effect (S1), Base sample with medication effect (S2), four samples related to different times of the formalin test (S3-S6) and two samples after completion of formalin test (S7, S8)]

* Significant differences between group 2 and group 4 (P<0.05)

HIAA

In groups 1 and 3 no significant differences were seen in HIAA concentrations at any of the time points. HIAA concentration within 0-15 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. HIAA concentration within 15-30 min after formalin injection in the fourth group was significantly higher than that of the second group. HIAA concentration within 30-45 and 45-60 min after formalin injection in the fourth group compared with second group showed no significant difference (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Concentrations of HIAA in different groups. [Base sample without medication effect (S1), Base sample with medication effect (S2), four samples related to different times of the formalin test (S3-S6) and two samples after completion of formalin test (S7, S8)]

* Significant differences between group 2 and group 4 (P<0.05)

Discussion

The ICV injection of CGRP significantly decreased nociceptive scores in the acute, middle and chronic phases of the formalin test. CGRP has increased the concentrations of norepinephrine, HMPG, dopamine, DOPAC, serotonin and HIAA in the acute and middle phases of the formalin test. CGRP has increased the concentrations of norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and their metabolite in the beginning of the chronic phase of the formalin test.

PAG region is one of the most important centers in descending pain control pathway (21). Descending impulses from the brain stem structures to the spinal cord inhibit the transmission of pain signals in the spinal cord (22). Norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin which have an important role in the analgesic systems are closely related to each other (23).

It seems that CGRP is involved in modulating pain information in the spinal cord and thus has an analgesic effect in the brain (24). CGRP is widely expressed in neurons of the central and peripheral nervous systems and often interacts with other neurotransmitters (25-27). CGRP causes the release of neurotransmitters and neural response to harmful stimuli and leads to the central sensitization in response to chronic pain (28-30). Intra-NRM injection of CGRP has antinociceptive effect which increases hind paw withdrawal latency (24). Intrathecal administration of CGRP has reciprocal effects in rat (31). CGRP was shown to induce c- Fos expression in the spinal cord and to increase thermal and mechanical modalities of pain (32).

Our data showed that ICV injection of CGRP significantly reduced pain-related behaviors during the acute and middle phases of formalin test. The analgesic effect we observed in the acute phase of the formalin test is consistent with the results of other researchers. CGRP injection into PAG has been shown to inhibit information transmission in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord by activating CGRP1 receptors and by activating descending pain systems in the hind paw withdrawal latency model of pain (33). CGRP injection into the raphe magnus nucleus is also reported to reduce pain in the same model of pain. By connecting to its receptor (primarily in PAG), CGRP performs many of its functions (34). Microdialysis data of this study showed that concentrations of norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and their metabolites increase in dialysates of PAG in acute and middle phases (0-15 min) of formalin test. These results imply that analgesic effects seen in the acute phase and the middle phase of the formalin are mediated by the monoaminergic pathways in the brain.

ICV injections of CGRP significantly decreased pain-related behaviors in the chronic phase of the formalin test. CGRP has increased the concentrations of norepinephrine and HMPG at intervals of 15-30 min from the chronic phase of the formalin test. Dopamine and DOPAC concentrations increased at intervals of 15-30 min from the chronic phase of the formalin test. Serotonin concentrations increased at intervals of 15-30 and 30-45 min and HIAA increased at intervals of 15-30 min in the formalin test.

Conclusion

CGRP significantly reduces formalin induced pain when injected in the cerebroventricular of rats. These effects are accompanied by an increase in the concentrations of norepinephrine, HMPG, dopamine, DOPAC, serotonin, and HIAA in the PAG nucleus. The increase of monoamines in PAG may be due to the action of CGRP in PAG or its related nuclei. However, the mechanisms underlying the increasing effects of CGRP on the CSF levels of monoamines as well as the nature of CGRP receptors involved need further investigation.

Acknowledgment

The results described in this paper were part of PhD student thesis with research project number (95225) was supported by School of Veterinary Medicine, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

References

- 1.Vanegas H, Schaible H-G. Descending control of persistent pain: inhibitory or facilitatory? Brain Res Rev. 2004;46:295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fields HL BA, Heinricher MM. Central nervous system mechanisms of pain modulation. In: McMahon S, Koltzenburg M, editors. Textbook of Pain Burlington. 5th ed. Massachusetts, USA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005. pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourgeais L, Monconduit L, Villanueva L, Bernard JF. Parabrachial internal lateral neurons convey nociceptive messages from the deep laminas of the dorsal horn to the intralaminar thalamus. J Neurosci Res. 2001;21:2159–2165. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-02159.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannister K, Dickenson AH. What do monoamines do in pain modulation? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10:143–148. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwiat GC, Basbaum AI. Organization of tyrosine hydroxylase- and serotonin-immunoreactive brainstem neurons with axon collaterals to the periaqueductal gray and the spinal cord in the rat. Brain Res. 1990;528:83–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90198-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durham PL, Vause CV. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) receptor antagonists in the treatment of migraine. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:539–548. doi: 10.2165/11534920-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho TW, Edvinsson L, Goadsby PJ. CGRP and its receptors provide new insights into migraine pathophysiology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:573–582. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sexton PM, McKenzie JS, Mendelsohn FA. Evidence for a new subclass of calcitonin/ calcitonin gene-related peptide binding site in rat brain. Neurochem Int. 1988;12:323–335. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(88)90171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henke H, Tschopp FA, Fischer JA. Distinct binding sites for calcitonin gene-related peptide and salmon calcitonin in rat central nervous system. Brain Res. 1985;360:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sexton PM, McKenzie JS, Mason RT, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, Mendelsohn FA. Localization of binding sites for calcitonin gene-related peptide in rat brain by in vitro autoradiography. J Neurosci Res. 1986;19:1235–1245. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruger L, Mantyh PW, Sternini C, Brecha NC, Mantyh CR. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the rat central nervous system: patterns of immunoreactivity and receptor binding sites. Brain Res. 1988;463:223–244. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sexton PM. Central nervous system binding sites for calcitonin and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Mol Neurobiol. 1991;5:251–273. doi: 10.1007/BF02935550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker CS, Hay DL. CGRP in the trigeminovascular system: a role for CGRP, adrenomedullin and amylin receptors? Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1293–1307. doi: 10.1111/bph.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pozo-Rosich P, Storer RJ, Charbit AR, Goadsby PJ. Periaqueductal gray calcitonin gene-related peptide modulates trigeminovascular neurons. Cephalalgia: Cephalalgia. 2015;35:1298–1307. doi: 10.1177/0333102415576723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Storer RJ, Akerman S, Goadsby PJ. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) modulates nociceptive trigeminovascular transmission in the cat. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:1171–1181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pecile A, Guidobono F, Netti C, Sibilia V, Biella G, Braga PC. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: antinociceptive activity in rats, comparison with calcitonin. Regul Pept. 1987;18:189–199. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(87)90007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welch SP, Cooper CW, Dewey WL. An investigation of the antinociceptive activity of calcitonin gene-related peptide alone and in combination with morphine: correlation to 45Ca++uptake by synaptosomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;244:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GPaxinos CW. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 6th, editor. Sydney: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dubuisson D, Dennis SG. The formalin test: a quantitative study of the analgesic effects of morphine, meperidine, and brain stem stimulation in rats and cats. Pain. 1977;4:161–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coderre TJ, Fundytus ME, McKenna JE, Dalal S, Melzack R. The formalin test: a validation of the weighted-scores method of behavioural pain rating. Pain. 1993;54:43–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90098-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gebhart GF. Descending modulation of pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27:729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ossipov MH, Dussor GO, Porreca F. Central modulation of pain. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3779–3787. doi: 10.1172/JCI43766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Ramirez DL, Calvo JR, Hochman S, Quevedo JN. Serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline adjust actions of myelinated afferents via modulation of presynaptic inhibition in the mouse spinal cord. PloS One. 2014;9:189–199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Brodda-Jansen G, Lundeberg T, Yu LC. Anti-nociceptive effects of calcitonin gene-related peptide in nucleus raphe magnus of rats: an effect attenuated by naloxone. Brain Res. 2000;873:54–59. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su HC, Wharton J, Polak JM, Mulderry PK, Ghatei MA, Gibson SJ, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity in afferent neurons supplying the urinary tract: combined retrograde tracing and immunohistochemistry. J Neurosci Res. 1986;18:727–747. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(86)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harmann PA, Chung K, Briner RP, Westlund KN, Carlton SM. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) in the human spinal cord: a light and electron microscopic analysis. The J Comp Neurol. 1988;269:371–380. doi: 10.1002/cne.902690305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poyner DR. Calcitonin gene-related peptide: multiple actions, multiple receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;56:23–51. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90036-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dobolyi A, Irwin S, Makara G, Usdin TB, Palkovits M. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-containing pathways in the rat forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489:92–119. doi: 10.1002/cne.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seybold VS. The role of peptides in central sensitization. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009:451–491. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79090-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sprenger T, Goadsby PJ. Migraine pathogenesis and state of pharmacological treatment options. BMC Med. 2009;7:65–76. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khoshdel Z, Takhshid MA, Owji AA. Intrathecal amylin and salmon calcitonin affect formalin induced c-Fos expression in the spinal cord of rats. Iran J Med Sci. 2014;39:543–551. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cridland RA, Henry JL. Effects of intrathecal administration of neuropeptides on a spinal nociceptive reflex in the rat: VIP, galanin, CGRP, TRH, somatostatin and angiotensin II. Neuropeptides. 1988;11:23–32. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(88)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu L-C, Weng X-H, Wang J-W, Lundeberg T. Involvement of calcitonin gene-related peptide and its receptor in anti-nociception in the periaqueductal grey of rats. Neurosci Lett. 2003;349:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker CS, Conner AC, Poyner DR, Hay DL. Regulation of signal transduction by calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]