Abstract

Objective(s):

Methamphetamine (METH) is a powerful stimulant drug that directly affects the brain and induces neurological deficits. B12 is a water-soluble vitamin (vit) that is reported to attenuate neuronal degeneration. The goal of the present study is to investigate the effect of vitamin B12 on METH’s neurodegenerative changes.

Materials and Methods:

Two groups of 6 animals received METH (10 mg/kg, interaperitoneally (IP)) four times with a 2 hr interval. Thirty mins before METH administration, vit B12 (1 mg/kg) or normal saline were injected IP. Animals were sacrificed 3 days after the last administration. Caspase proteins levels were measured by Western blotting. Also, samples were examined by TUNEL assay to detect the presence of DNA fragmentation. Reduced glutathione (GSH) was also determined by the Ellman method.

Results:

The pathological findings showed that vit B12 attenuates the gliosis induced by METH. Vit B12 administration also significantly decreased the apoptotic index in the striatum and the cerebral cortex (P<0.001). It also reduced caspase markers compared to the control (P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively). Interestingly, co-administration of METH and Vit B12 elevates the levels of GSH in both regions of the brain and returned it to normal levels compared to the METH group.

Conclusion:

The current study suggests that parenteral vit B12 at safe doses may be a promising treatment for METH-induced brain damage via inhibition of neuron apoptosis and increasing the reduced GSH level. Research focusing on the mechanisms involved in the protective responses of vit B12 can be helpful in providing a novel therapeutic agent against METH-induced neurotoxicity.

Keywords: Cerebral cortex Methamphetamine Neurotoxicity, Striatum, Vitamin B12

Introduction

Methamphetamine (METH) (also called meth, speed, chalk, crystal, and ice among other common slang terms) is a powerful stimulant drug with chemical structure similar to amphetamine. Relative ease of access and low cost of synthesis are among the reasons that METH abuse is on the rise (1, 2). METH can be snorted, smoked, injected or taken orally for therapeutic and recreational purposes. METH use in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and also in short term use in obesity has been approved by the FDA (3). METH rapidly crosses the blood brain barrier and penetrates into the brain and CSF. METH abuse can adversely affect health and cause long-term complications (4, 5). Even in small amounts, METH can lead to loss of appetite, increase in physical activity, confusion and produce wakefulness and euphoria (6). METH also affects the cardiovascular system and increases blood pressure, heart rate and risk for stroke and heart attack (7). Pharmacological and psychological effects of amphetamine derivatives are due to enhanced neurotransmitters (serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine) release from nerve endings (8). Direct effects of METH on the brain can induce neurological deficits via chemical and molecular changes that may lead to serious health hazard (9). It seems that different mechanisms are involved in METH- induced neurotoxicity like generation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species, glutathione depletion and cell death (10). No standard therapy is currently available to reverse METH’s neurotoxic effects (11).

Vitamin B12 (Vit B12) is a water-soluble vitamin that possesses anti-inflammatory and analgesic pro-perties (12). Vit B12 is reported to attenuate neuronal degeneration. It is the source of a coenzyme that participates in folate metabolism and thus plays a vital role in nucleotide synthesis (13). Therefore, vit B12 deficiency can lead to serious anemia, neuropathy and impaired brain function. Peripheral neuropathy in vit B12 deficiency is well established in animal and human studies (14). Therefore, vit B12 may interfere with some important mechanisms that are involved in METH neurotoxicity. The goal of the present study is to investigate the effect of vitamin B12 on METH’s neurodegenerative changes.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Vit B12 1000 µg/ml injection vial was obtained from Raha Pharmaceutical Company, Iran. METH was donated by the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, School of Pharmacy, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (Mashhad, Iran).

Animal treatment

Male BALB/c mice, weighing 30–35 g were provided from the Animals Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. Animals were maintained on a controlled temperature (22±3 °C), 12:12 hr light cycle and allowed free access to food and water. All experimental procedures were conducted according to the ethical standard and protocols approved by the Animal Experiments Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran. Animals were divided into 4 groups, with 6 mice in each group. Treated animals received METH at a dose of 10 mg/kg IP four times with a 2 hr interval (15). Thirty mins before METH administration, vit B12 (1 mg/kg) or normal saline in the same volume was injected IP. Control and sham groups received normal saline and vit B12 (1 mg/kg) respectively in the same route and at the same time. During the experiments, all groups were observed for mortality and general appearance. Animals were sacrificed 3 days after the last administration. In the next step, the brain tissues were removed and divided into two hemispheres. In order to measure the expression level of caspase proteins as well as glutathione content, the cortex and striatum from one-half of the brain were punched out and stored at -80 °C and the other half was fixed in 10% formalin for pathological investigation.

Histological analysis

Formalin fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and cut into sections with 5 µm thickness. Two slides per animal were prepared (twelve slides in each group) and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

TUNEL assay

In situ cell death was detected in brain tissue using the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated duTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) commercial kit (Roche/Germany). According to the kit instruction, tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and covered with proteinase K solution for protein digestion. H2O2 solution used to quench the endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were then exposed to TUNEL reaction mixture for 1 hr at 37 °C. After blocking the slide with a 3% BSA, one drop of peroxidase-labeled digoxigenin sheep Fab antibody was placed onto the slide in the presence of DAB (diaminobenzidine) substrate and counterstained with hematoxylin. Apoptotic index was calculated by counting the number of TUNEL-positive cell nuclei/total number of cell nuclei per field. Ten randomly microscopic fields per slide and two slides per animal were studied.

Western blot analysis

Western blot was carried out to detect caspase - 3 and 9 activities. The tissue samples were added to homogenization buffer in ice and mechanically homogenized. After centrifugation, the total protein content was estimated using the Bradford method. The specific volume of proteins extraction was loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE and separated by electrophoresis. At the next step, proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane and blocked with 5% skim milk. The blots were then incubated with primary antibodies (caspase-3, abcam, ab4051; caspase-9, abcam, ab47537). HRP secondary antibody (Cell Signaling, #7074) was used for chemiluminescent detection. The band size was analyzed using UVtec software (UK) and normalized against beta actin intensity (16).

Estimation of reduced glutathione level

In order to measure glutathione (GSH) content, tissue homogenates were mixed with equal amount of 10% trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation, the Ellman’s regent in PBS (phosphate buffer) was added to supernatant. Within 10 min, the change of absorbance was measured at 412 nm in a spectrophotometer. The amount of GSH is determined using standard curve.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean±SE and analyzed using ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test. The alpha level was set at 0.05. Data analysis was performed using SPSS Version 21.

Results

All animals were alive until the end of the experiments.

Histological analysis

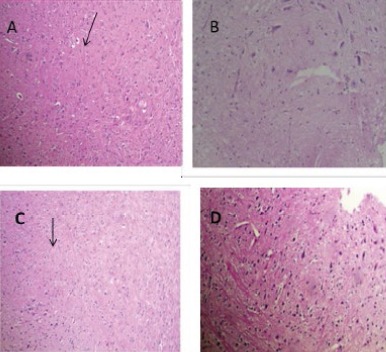

The pathological findings showed that METH exposure causes marked gliosis in striatum and cortex regions. Vit B12 at a dose of 1 mg/kg attenuates the gliotic response. No pathological finding was observed in the control and sham groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Histolpathogical analysis of brain tissue in mice. METH exposure at a dose of 10 mg/kg IP injection induced gliosis in cortex and striatum (A and C, respectively). Arrows indicate Rosenthal fibers. Vit B12, control or sham groups did not show any pathological effects in both regions (B and D). (H&E × 100)

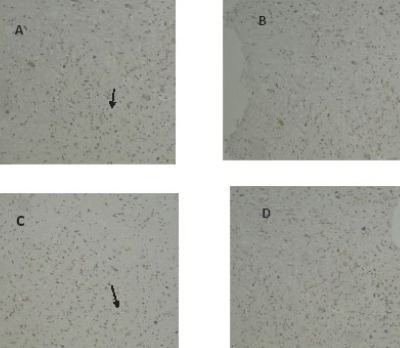

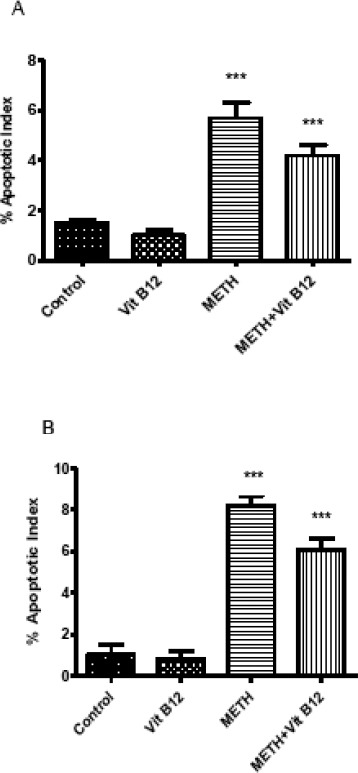

Tunel assay

The TUNEL technique revealed the potential of METH-induced DNA fragmentation in brain tissues (Figure 2). The percentage of TUNEL positive cells in striatum and cerebral cortex were significantly increased in groups that received METH in comparison with control (P<0.001). Treatment with vit B12 reduced the damage in cerebral cortex and striatum significantly compared to the group that received METH (P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Apoptotic profile of METH in the striatum and cerebral cortex of rat (A and C, respectively). Treatment with vit B12 reduced the METH-induced cell death in both regions (B and D)

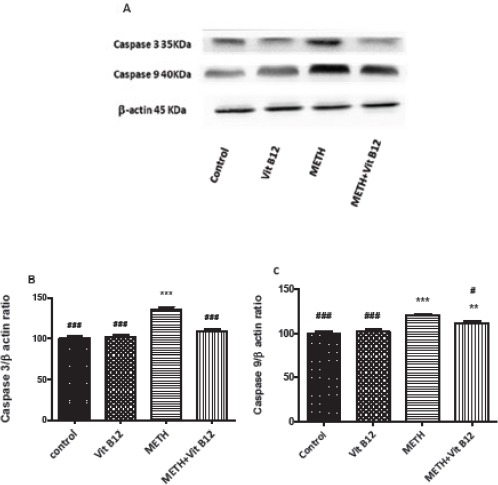

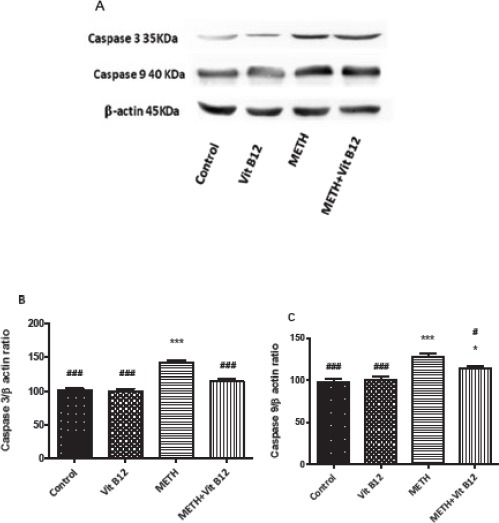

Western blot analysis

The effect of METH on caspase-3 and 9 expression was investigated using Western blot analysis. Figure 4 and 5 show that METH exposure at dose of at dose of 10 mg/kg IP for four times upregulates the expression of caspase-3 and 9 in both regions compared to the control group (P<0.001). Co-administration of vit B12 and METH significantly decreased the level of caspase-3 and 9 proteins in the cerebral cortex and striatum compared to the group that received METH alone (P<0.001 and P<0.05, respectively).

Figure 4.

Effect of normal saline, vit B12, METH or METH+vit B12 on the protein level of caspase 3 and 9 in the rat brain cortex. (A) Representative photograph of the Western blot analysis. Densitometric analysis of caspase-3 (B) and caspase-9 level (C). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001compared to the control group. #P<0.05 and ###P<0.001compared to the METH group

Figure 5.

Effect of normal saline, vit B12, METH or METH + vit B12 on the protein level of caspase-3 in rat brain striatum. (A) Representative photograph of the Western blot analysis. Densitometric analysis of caspase-3 (B) and caspase-9 level (C). Data are expressed as mean±SEM. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001compared to the control group. #P<0.05 and ###P<0.001compared to the METH group

Figure 3.

Effect of normal saline, vit B12, METH or METH + vit B12 on cerebral cortex (A) and striatum (B) apoptosis as revealed by TUNEL assay. Values are presented as mean±SEM. ***P<0.001 compared to control group

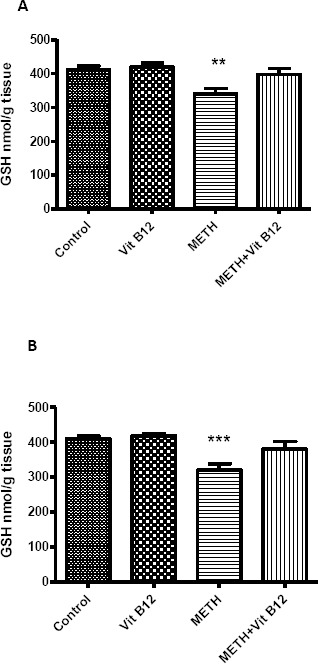

Glutathione levels in striatum and cortex

METH treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the GSH level in the rat brain cortex and striatum as compared with a control group (P<0.01 and P<0.001, respectively). Co-administration of METH and vit B12 increased GSH levels in both regions of the brain and returned it to normal levels. Vit B12 alone did not change the GSH level in comparison with the control group (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effect of normal saline, vit B12, METH or METH + vit B12 on reduced glutathione (GSH) level in rat brain cortex (left Chart) and striatum (right chart). Data analyzed by ANOVA followed by Tukey-kramerpost test and are presented as mean±SEM. **P<0.01, *** P<0.001 and *** P<0.001 as compared to control group

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that vit B12 can decrease the METH-induced nerve damage. METH is a neurotoxic drug and induces degeneration on different parts of the brain (17, 18). The pathological findings revealed that METH exposure causes marked gliosis in striatum and cortex regions. Gliosis refers to the proliferation of glia cells in response to CNS insult and is characterized by increased expression of glial-specific markers and morphological changes (19). According to our results, vit B12 at a dose of 1 mg/kg was able to abolish the gliotic response. In an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model in rat, treatment with vit B12 and honey bee venom decreased the inflammation and gliosis level (20). B-group vitamins including B1, B6 and B12 are considered for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Vit B12 plays an important role in nervous system structure and function (21-23).

The acute and chronic IP injection of METH is also associated with oxidative DNA damage and programmed cell death in the brain, especially in the nucleus accumben, a part of ventral striatum (24). It was demonstrated that METH even at single IP injection (30 mg/kg) can induce striatal apoptosis (15). Studies have shown that METH causes damage to striatal dopaminergic and non-monoaminergic cortical neurons (25, 26). Current study results from the TUNEL assay showed that the METH administration increases the apoptosis index in cortical and specially striatal neurons. In elucidating the molecular events related to METH-induced apoptotic changes observed in the TUNEL assay, two caspase levels were measured by Western blotting technique. Activation of caspase-3 and 9 especially in the striatum indicated a role for intrinsic pathway in METH neurotoxicity. Other investigations also confirmed the mitochondrial pathway activation by METH toxicity. The injections of a single dose of 40 mg/kg METH resulted in an increase of pro-apoptotic/ anti- apoptotic (BAX (BAD)/Bcl-2) ratio in neocortex of mouse (27). METH exposure to immortalized rat striatal cell line also increased the caspase-9, cytochrome c level and BAX/Bcl-2 gene expression (17). The result of one study showed that the administration of vit B12 in separate or combined with diclofenac and celecoxib can exert neuroprotective effect in tibial nerve-crushed model in rats. Vit B12 recovered the motor function and reduced the axonal degeneration and glial cell proliferation (Wallerian degeneration response)(28). It is reported that vit B12 increases the number of regenerating neurons and attenuates neuronal damage after sciatic nerve injury (29).

METH can damage neurons by causing dopamine-dependent oxidative stress. Recent studies indicated that METH decreases striatal ATP, induces oxidative damage and produces free radicals. Additionally, antioxidants and spin trapping agents can protect against METH-induced toxicity (30-32). The reduced GSH content in the current study was decreased by METH administration in the striatum and cortex and was restored to normal levels by vit B12 pretreatment. Vit B12 exerts its antioxidant activity in different ways. It is able to inhibit nitric oxide production, intracellular oxidative stress and cellular apoptosis (33). Interestingly, it has been reported that vit B12 can preserve GSH status and the thiol groups of enzymes in the reduced state (34). Our findings confirmed that oxidative stress plays an important role in METH neurotoxicity and antioxidant agent like vit B12 can prevent the neurotoxic effect of METH and increase the GSH level.

Conclusion

The current study suggests that parenteral vit B12 at safe doses may be a promising treatment for METH-induced brain damage via inhibition neuron apoptosis and increasing the reduced GSH level. Research focusing on the mechanisms involved in protective responses of vit B12 can be helpful in providing a novel therapeutic agent against the METH-induced neurotoxicity.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to the Vice Chancellor for Research, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran and Iran National Science Foundation for financial support.

References

- 1.Cadet JL, Krasnova IN, Jayanthi S, Lyles J. Neurotoxicity of substituted amphetamines: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Neurotox Res. 2007;11:183–202. doi: 10.1007/BF03033567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chulathidaa C, Summon C. Global patterns of methamphetamine use. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:269–274. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kishi T, Ikeda M, Kitajima T, Yamanouchi Y, Kinoshita Y, Kawashima K, et al. Prostate apoptosis response 4 gene is not associated with methamphetamine-use disorder in the Japanese population. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1139:83–88. doi: 10.1196/annals.1432.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiyatkin EA, Sharma HS. Acute methamphetamine intoxication: brain hyperthermia, blood-brain barrier, brain edema, and morphological cell abnormalities. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2009;88:65–100. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)88004-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rusyniak DE. Neurologic manifestations of chronic methamphetamine abuse. Neurol Clin. 2011;29:641–655. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karch SB. Karchs Pathology of Drug Abuse. 3rd ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin WR, Sloan JW, Sapira JD, Jasinski DR. Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1971;12:245–258. doi: 10.1002/cpt1971122part1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothman RB, Baumann MH. Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:23–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ladenheim B, Krasnova IN, Deng X, Oyler JM, Polettini A, Moran TH, et al. Methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity is attenuated in transgenic mice with a null mutation for interleukin-6. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:1247–1256. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.6.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barayuga SM, Pang X, Andres MA, Panee J, Bellinger FP. Methamphetamine decreases levels of glutathione peroxidases 1 and 4 in SH-SY5Y neuronal cells: protective effects of selenium. Neurotoxicology. 2013;37:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghadiri A, Etemad L, Moshiri M, Moallem SA, Jafarian AH, Hadizadeh F, and M, et al. Exploring the effect of intravenous lipid emulsion in acute methamphetamine toxicity. IJBMS. 2017;20:138–144. doi: 10.22038/ijbms.2017.8236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseinzadeh H, Taiari S, Nassiri-Asl M. Effect of thymoquinone, a constituent of Nigella sativa L on ischemia-reperfusion in rat skeletal muscle. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2012;385:503–508. doi: 10.1007/s00210-012-0726-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carr DF, Whiteley G, Alfirevic A, Pirmohamed M, Fol A st. Investigation of inter-individual variability of the one-carbon folate pathway: a bioinformatic and genetic review. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009;9:291–305. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scalabrino G, Corsi MM, Veber D, Buccellato FR, Pravettoni G, Manfridi A, et al. Cobalamin (vitamin B(12)) positively regulates interleukin-6 levels in rat cerebrospinal fluid. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;127:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu JP, Xu W, Angulo N, Angulo JA. Methamphetamine-induced striatal apoptosis in the mouse brain: comparison of a binge to an acute bolus drug administration. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etemad L, Jafarian AH, Moallem SA. Pathogenesis of pregabalin-induced limb defects in mouse embryos. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;18:882–889. doi: 10.18433/j3pp5z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bigdeli L, Asia MN, Miladi-Gorji H, Fadaei A. The spatial learning and memory performance in methamphetamine-sensitized and withdrawn rats. IJBMS. 2015;18:234–239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng X, Cai NS, McCoy MT, Chen W, Trush MA, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine induces apoptosis in an immortalized rat striatal cell line by activating the mitochondrial cell death pathway. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:837–845. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tong J, Fitzmaurice P, Furukawa Y, Schmunk GA, Wickham DJ, Ang lC, et al. Is brain gliosis a characteristic of chronic methamphetamine use in the human? Neurobiology of Disease. 2014;67:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karimi A, Parivar K, Nabiuni M, Haghighi S, Imani S. Effect of honey bee venom and vitamin B12on gliosis of brain stem in rats with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis-animal model for multiple sclerosis. Journal of cell & tissue. 2011;1:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosseinzadeh H, Moallem SA, Moshiri M, Sarnavazi M S, Etemad L. Anti-nociceptive and Anti-infl ammatory Effects of cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) against acute and chronic pain and inflammation in mice. Arzneimittelforschung. 2012;62:324–329. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lalonde R, Barraud H, Ravey J, Gueant JL, Bronowicki JP, Strazielle C. Effects of a B-vitamin-deficient diet on exploratory activity, motor coordination, and spatial learning in young adult BALB/c mice. Brain Res. 2008;1188:122–131. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganguly P, Alam SF. Role of homocysteine in the development of cardiovascular disease. Nutr J. 2015;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tokunaga I, Ishigami A, Kubo S, Gotohda T, Kitamura O. The peroxidative DNA damage and apoptosis in methamphetamine-treated rat brain. J Med Invest. 2008;55:241–245. doi: 10.2152/jmi.55.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisch AJ, Marshall JF. Methamphetamine neurotoxicity: dissociation of striatal dopamine terminal damage from parietal cortical cell body injury. Synapse. 1998;30:433–445. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199812)30:4<433::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halpin LE, Collins SA, Yamamoto BK. Neurotoxicity of methamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. Life Sci. 2014;97:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayanthi S, Deng X, Bordelon M, McCoy MT, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes differential regulation of pro-death and anti-death Bcl-2 genes in the mouse neocortex. FASEB J. 2001;15:1745–52. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0025com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamaddonfard E, Farshid AA, Samadi F, Eghdami K. Effect of vitamin B12on functional recovery and histopathologic changes of tibial nerve-crushed rats. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2014;64:470–475. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hobbenaghi R, Javanbakht J, Hosseini E, Mohammadi S, Rajabian M, Moayeri P, et al. Neuropathological and neuroprotective features of vitamin B12on the dorsal spinal ganglion of rats after the experimental crush of sciatic nerve: an experimental study. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:123. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-8-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 30.Harold C, Wallace T, Friedman R, Gudelsky G, Yamamoto B. Methamphetamine selectively alters brain glutathione. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;400:99–102. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirecki A, Fitzmaurice P, Ang L, Kalasinsky KS, Peretti FJ, Aiken SS, et al. Brain antioxidant systems in human methamphetamine users. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1396–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kousik SM, Graves SM, Napier TC, Zhao C, Carvey PM. Methamphetamine-induced vascular changes lead to striatal hypoxia and dopamine reduction. Neuroreport. 2011;22:923–928. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32834d0bc8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manzanares W, Hardy G. Vitamin B12: the forgotten micronutrient for critical care. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:662–668. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833dfaec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wheatley C. A scarlet pimpernel for the resolution of inflammation? The role of supra-therapeutic doses of cobalamin, in the treatment of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic or traumatic shock. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:124–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]