Abstract

Background and Aim

Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus), a widely distributed small mammal in the South Asian region, can carry helminths of zoonotic importance. The aim of the study was to know the prevalence and diversity of gastrointestinal (GI) helminths in free-ranging Asian house shrew (S. murinus) in Bangladesh.

Materials and Methods

A total of 86 Asian house shrews were captured from forest areas and other habitats of Bangladesh in 2015. Gross examination of the whole GI tract was performed for gross helminth detection, and coproscopy was done for identification of specific eggs or larvae.

Results

The overall prevalence of GI helminth was 77.9% (67/86), with six species including nematodes (3), cestodes (2), and trematodes (1). Of the detected helminths, the dominant parasitic group was from the genus Hymenolepis spp.(59%), followed by Strongyloides spp.(17%), Capillaria spp. (10%), Physaloptera spp. (3%), and Echinostoma spp.(3%).

Conclusion

The finding shows that the presence of potential zoonotic parasites (Hymenolepis spp. and Capillaria spp.) in Asian house shrew is ubiquitous in all types of habitat (forest land, cropland and dwelling) in Bangladesh. Therefore, further investigation is crucial to examine their role in the transmission of human helminthiasis.

Keywords: Asian house shrew, Bangladesh, gastrointestinal helminths, prevalence, Suncus murinus

Introduction

Shrews, belonging to the order Insectivora and under the family of Soricidae and the genus Suncus, are extensively distributed in Asia, Africa, and Europe [1]. Of the 18 currently recognized species of Suncus, only two species, namely Suncus murinus, the house shrew (Chika or Chucho), and S. etruscus, the pygmy shrew (Baman Chika), are native to Bangladesh. The first one is very common and found in the holes and drains of urban and rural areas and forests, whereas the latter one is very rare, and no recent sight has been recorded [2]. Shrews’ feed habit is restricted almost entirely to invertebrate prey. Shrew plays an important role as reservoirs and hosts of many pathogens of animals and humans [3]. They are commensal with humans and are primarily found near human habitation and other synanthropic habitats such as rice fields and grain warehouses [4]. Asian house shrew is the natural reservoir of Thottapalayam virus [5], Hantavirus [6], Plague [7], and Toxoplasma gondii [8].

The invertebrate diet of shrews predisposes them to infestation by helminth parasites. Helminth parasites in small mammals comprise four major taxonomic groups: The cestodes or tapeworms, the flukes, the nematodes or roundworms, and the acanthocephalans or spiny-headed worms. Almost all of the cestodes, flukes, and acanthocephalans, as well as many of the nematodes, require one or more invertebrate intermediate hosts for the development of their larval stages to complete their life cycles [9]. The vertebrate’s definitive host becomes infected either as a result of direct penetration of their tegument by larval stages or by ingestion of infective stages, the latter being the more usual route, especially in the case of helminths of terrestrial vertebrates [10,11]. Thus, the shrew will become infected with helminth parasites through its food and is likely to harbor a more diverse helminth fauna than the other sympatric small mammals. This has been confirmed by previous studies of British small mammals [11,12].

Parasites have a key role in ecosystem, affecting the ecology and evolution of specific interaction, final host population growth, and biodiversity of the community [13,14]. Ecology may have direct pathological effects on host survival and reproduction, whereas indirect effect may be the reduction of the hosts’ body condition [15]. Anthropogenic land use change is leading to novel interactions among ecological factors related to vectors, hosts, and disease [16]. Predicting the influence of land gradient on parasite incidence is important but challenging. Because, very little is known about many wildlife diseases, especially in context of Bangladesh where no baseline study was done on shrews.

In different studies, factors such as habitat selection, elevation distributions, diet, nest type, and participation in colonies or mixed-species were found to influence parasitic infestation rates [17] in host or vector community [18]. Many studies have been conducted on evaluating the prevalence of parasites among wild rats throughout the world [4,19]. Although there have been several reports of helminth infestations in shrews and rodents from other parts of the world [4,20], but studies from Bangladesh are very limited. So far known, no epidemiological and molecular data exist regarding the helminth infestations and diversity among shrews in Bangladesh.

There are several diagnostic techniques for parasite species identification such as qualitative, quantitative, and culture. Among different diagnostic methods, qualitative techniques are more convenient, easy to perform, and economic. Every technique has several limitations. It is difficult to differentiate different species of parasites using single diagnostic technique. To avoid such types of limitations, combined recovery of eggs from fecal samples using flotation and sedimentation is recommended [18] along with direct smear. Collection of gross parasites by necropsy and identification of parasites provide more accuracy of species identifications.

The close association between insectivores, humans and their livestock along with their exposure to blood-sucking arthropods, beetles, cockroaches, and other invertebrates, extends the scope for transmission of helminths. The parasitic infestations that shrew harbor and convey to human or animal populations have not been thoroughly investigated, especially in over-populated countries like Bangladesh. As the density of human population continues to increase exponentially, speeding the reduction and fragmentation of animal habitats, greater human-animal contact is inevitable, and even higher rates of pathogen transmission are likely. Thus, interest has grown in collecting baseline data on patterns of parasitic infestations in shrew’s populations as an index of their health and to assess and manage disease risks to human.

Therefore, the study was aimed at understanding the diversity and prevalence of helminths fauna of Asian house shrews and the role of environmental factors in facilitating helminth infestation in S. murinus in Bangladesh.

Materials and Methods

Ethical approval

The Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of Chittagong Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Bangladesh (CVASU-AEEC), approved the study protocol and the approval number for the project was CVASU/Dir (R and E) AEEC/2015/07.

Study period and area

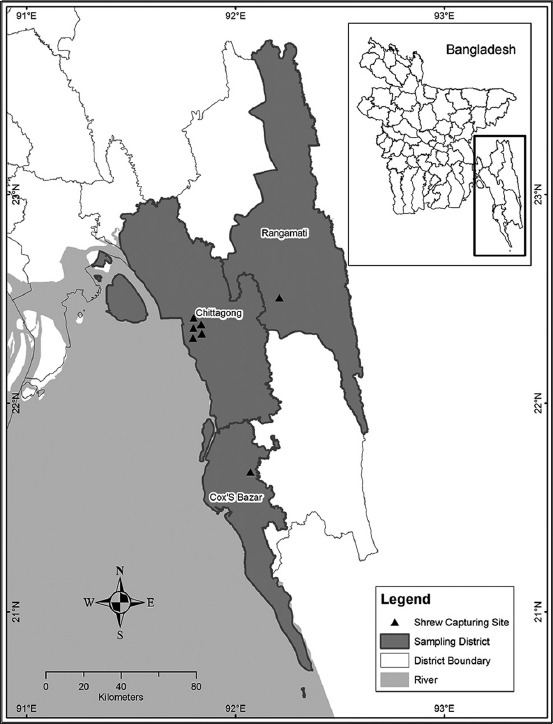

A 6-month-long cross-sectional study was conducted in Chittagong division, Bangladesh, between July and December 2015. Three major sites were selected, with each location representing unique geographical location, and the areas were naturally decorated with mountains, rivers, forests, valley, and sea in southeastern part of Bangladesh. The studied areas are Chittagong Metropolitan area, Kaptai area of Rangamati district and,Chakaria area of Cox’s bazar district of Bangladesh (Figure-1). All the sites were characterized by subtropical climate and high humidity throughout the year, with temperature ranging between 26°C and 32°C and heavy rainfall coincided with the monsoon season (June to October).

Figure-1.

Distribution of shrew sampling sites.

Trapping of shrews

A total of 86 individuals of S. murinus (52 males and 34 females) were trapped from the study areas using live traps. Locally made steel wire cage traps (measuring 27 cm × 13 cm × 13 cm) in each sampling location site have proven correct efficiency in a preliminary sampling of medium- and large-sized shrews. All the traps were baited with ghee smearing biscuit and dried fish [21-23]. Every day, 42 traps were set at dusk and checked at the next dawn. The exact locations (latitude and longitude) of the habitats and traps area were recorded using a Global Positioning System device.

Sample collection

Isoflurane was used for induction of anesthesia followed by the killing of shrews inside a ziplock bag. The shrews were only handled out of the zip bag after been deeply euthanized, as soon as breathing and heart beating has stopped [22,24]. The captured Asian house shrews were identified based on morphometric parameters described by Payne et al. [25].

The shrews were dissected to dismantle all the internal organs where the helminths may be found. All the harvested organs were carefully searched for the presence of helminths in the presence of physiological saline. The whole gastrointestinal (GI) tract was preserved in a plastic box, specimen container, or in a plastic bag, filled with 70% alcohol as a fixative agent. A certain amount of feces was collected and stored in formalin for coproscopy. After removal of GI tract from the shrews, the remaining parts were kept in biohazard bags and the bags were properly buried.

Identification of helminths

The gut sample was spread out in a Petri dish. Few drops of 70% alcohol were poured into the Petri dish to facilitate the dissection. The direct smear was taken from the inner side of the specimens and then the smear was examined under a stereomicroscope. The gross helminths were carefully collected and relaxed in 2% lidocaine, then fixed in 70% alcohol, and stained by Mayer’s Paracarmine [21]. The eggs were counted under the stereomicroscope.

Staining of nematodes and cestodes

Nematodes were examined using Amman’s lactophenol. For cestodes, parasites were relaxed by placing them in warm saline and then flattened by placing them in between two slides and compressing the slides together using an elastic band. The pair of slides was placed in slightly hot alcohol-formalin-acetic acid solution for 20 min to fix the parasites in a flattened state, allowing the internal structures to be seen more clearly. After flattening, the specimens were transferred through an alcohol series to 70% alcohol before staining in Mayer’s Paracarmine.

Measuring of parasites

The parasites were transferred from the xylene onto a microscope slide using a brush with three bristles. A couple of drops of Canada balsam, DPX, or XAM were placed on the top of the specimen and a coverslip was gently lowered on the top of it using a mounted needle. Measurements of the various structures of the parasites were made using a micrometry.

Coproscopy

All fecal samples were examined under a compound light microscope both in wet mounts and flotation technique. Slides were initially examined in low magnification (10x) to trace followed by high magnification (100x) for identification of eggs or parasites [26,27]. Eggs of particular species and gross parasites were identified based on morphological characteristics (shape and shell structure) and size as described by Foreyt [27] and Sloss and Kemp [28].

Statistical analysis

The raw data were recorded accordingly using MS Excel 2013. The descriptive analysis was performed using STATA 13 (StataCrop, 4905, Lakeway Drive, College station, Texas 77845, USA). Associations among variables such as host origin, sex, age, anthropization, and parasitization were calculated by Chi-square (λ2) test or Fisher’s exact test when necessary. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The mean worm load was calculated by formula described by Opara and Fagbemi [29]. The mean worm load for each taxa was calculated as number of worm of each taxa from shrews of each land gradient divided by the total number of shrew positive for that parasitic taxa in that land gradient. Relative abundance was calculated as the total number of worm of each taxa found divided by the total number of shrew examined in a specific land gradient. The overall relative abundance was calculated as the total number of worm found in that land gradient shrew divided by the total number of shrews tested of that land gradient.

The helminth diversity was calculated following Shannon index, H = ∑(P1) IlnP1I [30], where P1 is the proportion of the total number of individual in the population that are in species “l.” The map of the study area was made based on the latitude and longitude collected during sampling using ArcGIS software.

Results

Based on gross parasite samples’ morphometric characteristics and eggs’ morphology, six helminths taxa were detected. Helminth genera included Hymenolepsis spp., Taenia spp., Capillaria spp. (Capillariidae), Strongyloides spp. (Strongyloididae), Physaloptera spp. (Physalopteridae), and Echinostoma spp. In forest areas, Taenia spp. and Physaloptera spp. were prevalent, whereas in croplands, Echinostoma spp. was prevalent, but in human settlement areas (dwelling), all of the taxa were present.

Overall prevalence

The prevalence, mean worm load, relative abundance, and species diversity of GI parasites were examined in accordance with the land gradient-forests, croplands, and dwelling areas. Of the 86 shrew from different land gradients, 67 (77.91%) were infected with one or more species of GI parasites, where cestode was the most prevalent than others (63%). However, the nematodes and trematodes were found by 31% and 3%, respectively. The cestodes were most prevalent in dwelling area, whereas nematodes and trematodes were more prevalent in croplands and forest areas. The most prevalent parasite was Hymenolepis spp. (59%), followed by Strongyloides spp. (17%), Capillaria spp. (10%), and others (Table-1). Among all the parasites identified in different land gradients, only Capillaria spp. has significantly higher prevalence in cropland area.

Table-1.

Prevalence of gastrointestinal helminths in Suncus murinus from the southeast part of Bangladesh (n=86) (Chi-square test).

| Phylum | Genus | Prevalence % (n) | p value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall prevalence (n=86) | Forest (n=22) | Dwelling (n=39) | Cropland (n=25) | ||||

| Cestode | Hymenolepis sp. | 59 (51) | 59 (13) | 67 (26) | 48 (12) | 0.268 | |

| Taenia spp. | 3 (3) | 0 | 5 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.561 | ||

| Nematode | Capillaria spp. | 10 (9) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 28 (7) | 0.003 | |

| Strongyloides spp. | 17 (15) | 23 (5) | 15 (6) | 16 (4) | 0.768 | ||

| Physaloptera spp. | 3 (3) | 0 | 2 (1) | 8 (2) | 0.317 | ||

| Trematode | Echinostoma spp. | 3 (3) | 5 (1) | 5 (2) | 0 | 0.518 | |

p value significant at<0.05

The mean worm loads of parasitic species varied from four to six and cropland had higher worm load and showed no significant relationship with another gradient area. The relative abundance of worm in dwelling area and species diversity in cropland area was higher in comparison to other areas (Table-2).

Table-2.

Mean worm load, relative abundance, and species diversity of helminths in Asian house shrews.

| Parasites (n) | Forest (n=22) | Dwelling (n=39) | Cropland (n=25) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSI | NPF | MWL | RA | SD | NSI | NPF | MWL | RA | SD | NSI | NPF | MWL | RA | SD | |

| Hymenolepis spp. (51) | 13 | 45 | 3.46 | 0.5 | 0.32 | 26 | 47 | 2 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 12 | 38 | 2.7 | 0.44 | 0.19 |

| Taenia spp. (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 100 | 1 | 1.16 | 0.07 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 1.16 | 0.03 |

| Capillaria spp. (9) | 1 | 8 | 8 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 1 | 8 | 12 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 7 | 8 | 12.1 | 0.09 | 0.14 |

| Strongyloides spp. (15) | 5 | 23 | 4.6 | 0.3 | 0.19 | 6 | 19 | 5.3 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 4 | 11 | 9.25 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Physaloptera spp. (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 4 | 0.29 | 0.04 | 2 | 25 | 4 | 0.13 | 0.05 |

| Echinostoma spp. (3) | 1 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0.06 | 2 | 29 | 3.5 | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 20 | 77 | 3.85 | 0.9 | 0.63 | 36 | 228 | 4 | 2.65 | 0.72 | 26 | 182 | 6 | 2.11 | 0.51 |

NB: NSI= No. of shrew infected; NPF= No. of parasites found; MWL= Mean worm load; RA= Relative abundance; SD= Species diversity

Among the infected shrews, one or more species of parasites in a single individual were commonly found. Parasitic infestation by single species was predominant in positive shrews of all the areas. Although maximum double and multiple parasitic infestations were found in dwelling area, all areas showed double and/or multiple parasitic infestations (Table-3).

Table-3.

Parasitic loads in individuals at different sites of the study area.

| Location | Single infestation | Double infestation (%) | Multiple infestation (>2) (%) | Negative infestation (%) | Total positive (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest area (n=22) | 14 (63.64) | 3 (13.64) | 0 | 5 (22.73) | 17 (77.27) |

| Cropland (n=25) | 15 (60.00) | 4 (16.00) | 1 (4.00) | 5 (20.00) | 20 (80.00) |

| Dwelling (n=39) | 21 (53.85) | 7 (17.95) | 2 (5.13) | 9 (23.08) | 30 (76.92) |

Only trematode infestation was not found in any shrew. All the trematode infestation were found in combination with cestodes and/or nematodes. Among the co-infestations, cestodes and nematodes were most common followed by cestodes and trematodes; nematodes and trematodes. Cestodes mostly infect individually in all types of land gradient.

The shrews in dwelling area were around 2 times more likely to be positive for Hymenolepis spp. than that of cropland. The shrews of cropland area were harboring 13 and 3 times more Capillaria spp.and Physaloptera spp., respectively, compared to shrews of dwelling area. The forest land shrews were at 2 times more risk of having Capillaria spp.and Strongyloides spp. than that of dwelling area (Table-4).

Table-4.

Measures of strengths for different helminths corresponding to land gradients.

| Parasites (n) | OR | p value* |

|---|---|---|

| Hymenolepididae gen. spp. (51) | ||

| Cropland | 1 | |

| Dwelling | 1.9 | 0.254 |

| Forest | 1.6 | 0.498 |

| Taeniidae gen spp. (3) | ||

| Cropland | 1 | |

| Dwelling | 1.2 | 0.89 |

| Forest | 0.02 | 0.994 |

| Capillaria spp. (9) | ||

| Dwelling | 1 | |

| Cropland | 12.8 | 0.023 |

| Forest | 2.06 | 0.618 |

| Strongyloides spp. (15) | ||

| Dwelling | 1 | |

| Cropland | 1.1 | 0.89 |

| Forest | 2.13 | 0.29 |

| Physaloptera spp.(3) | ||

| Dwelling | 1 | |

| Cropland | 3.3 | 0.34 |

| Forest | 0.02 | 0.988 |

| Echinostoma spp. (3) | ||

| Forest | 1 | |

| Dwelling | 1.3 | 0.825 |

| Cropland | 0.04 | 0.994 |

p value significant at <0.05

Discussion

The current study explored gastro-intestinal helminthic infestation of Asian house shrews from different geographies such as dwelling, cropland, and forest areas of Bangladesh. These are the first data and the only study to consider the whole helminth spectrum of the Asian house shrews from Bangladesh. Shrews were highly infected with various GI parasites in the study. We recovered six genera of helminths which are known to have pathogenic species affecting human and animals [19,31,32]. The species diversity, and mean worm load in cropland and relative abundance in dwelling area were higher where domestic animals and human activity were predominant. The presence or abundance of parasites was somewhat modified by the geography of the study areas but only to a limited extent. Dussex et al. [33] have found that shrews continuously migrate from agricultural land to the nearest household resulting in the nearly similar prevalence of parasites in Crocidura shrews of different region. In another study, similar findings were reported in topographically identical countries such as Taiwan and Cambodia, where the prevalence of helminthic infestation in Asian house shrews was 100% [23] and 66.67% [4], respectively. The abundance of parasites in shrews might be mainly due to their scavenging nature. Other than the narrow home range, high population density and scavenging near the domestic animals and human population might also have potential contributions [34].

The findings of identified cestode and nematode species in the current study agree with previous reports on Asian house shrew and some species can infect humans also [19,23]. The prevalence and intensity values were somewhat higher in the previous studies [19,26] than that of the present study. The above discrepancies are difficult to explain, but the prevalence and intensity values were quite similar to those obtained by Veciana et al. [4].

Taenia spp. was found in shrews of forest and cropland areas, which is considered to be the important species to cause the most neglected tropical disease of human worldwide [35-37]. Open defecation, the intermediate host having free access to human feces, and uncontrolled slaughtering of the infected host might be linked to human–Taenia spp. association [38].

Strongyloides spp. (the pinworm or roundworm) and Capillaria spp.were foundto be prevalent in shrews of the cropland and dwelling areas, which was also reported in shrews in Taiwan [19]. The mean worm load, relative abundance, and species diversity of Strongyloides spp. and Capillaria spp.were higher in cropland area where human-animal activity is regular. Small mammals are being crowded near the cropland due to habitat loss, which increases the level of contamination of the environment. Thus, the worm load, relative abundance, and species diversity are increasing in the environment. Different species of Capillaria have been identified from S. murinus in Cambodia [4]. However, the present study found that 9.30% of house shrews were infected, indicating the environments might be highly contaminated with the eggs of Capillaria spp.Among different risk factors associated with different species of parasitic infestation, significantly greater numbers of Strongyloides spp.was found in adult S. murinus. It can be readily explained by the fact that adults have a longer period over which they accumulate the parasite. The low intensity of infestation in the juveniles makes it unlikely that Strongyloides spp.infestations could cause their mortality in the autumn. The other differences in nematode fauna are not so readily explained but might be a combination of the longer period over which the adults have been able to accumulate infective stages and differences in feeding habits between adult and juvenile shrews.

Hymenolepis spp. was the most common cestode detected in this study similar to Central Taiwan [19] and also in rodents from Southeast Asia [12,26,39,40]. Due to the conditions in which our samples were preserved (70% ethanol), we were unable to determine which species of Hymenolepis was recovered.

We found that shrew harbors more helminth species and has multiple species per host individual in three-land gradient. A remarkable number of researchers around the world also noticed that shrews can harbor a wide range of helminths [41]. High parasitism of the shrew may imply higher absolute food requirement that might increase the parasitic colonization rate [42], but another study suggests that high infestation levels are either due to its generalized diet or high abundance, rather than its large body size [41]. The mean worm load or intensity and prevalence are correlated with contamination ofenvironment specially soil where the parasites need to develop to become infective [32]. Presence of parasites in shrews that are also prevalent in human and domestic animals is a clear indication of invasive species. These parasites might break their species barrier and are transmitted from animals to humans or vice versa. Sometimes, the water sources are shared by human, domestic animals, and wildlife that might influence the exposure to infective stages of various parasites of human and domestic animal [43,44], and the intensity of infestation can change with accessibility to water resources [45]. The host health status and nutrition also play a major role in parasitic infestation load [31] by directly influencing immune responses and acquisition of immunity against the parasites [46]. Although our results demonstrated an effect of habitat on helminth species richness, it also indicated that the observed patterns may be confounded by several aspects of the biology of shrews, such as their density or ranging patterns as both of these traits have been stated as potential robust determinants of helminth diversity [47].

The genus Hymenolepis is most notorious, causing a pathologic effect on human health. Two genera of Platyhelminthes – Hymenolepis and Echinostoma – have been identified in shrews of Bangladesh, which was supported by a previous study as the possible origin of zoonotic helminthiasis [48]. Commensal rodents and shrews, that are associated with humans, can also play a role in continuing the life cycle of echinostomes in human settlements. Before our study, an echinostomatid in S. murinus was recorded in Cambodia [4]. Although Artyfechinostomum malayanum (a species of Echinostome) has been reported previously in the Asian house shrew, eggs similar with Echinostome paraensei from Bangladesh have also been found [49]. The higher levels of infestation of Echinostoma spp.in adults are likely to be due to the longer time of exposure to infective stages.

In the present study, three S. murinus (3.49%) were found to be infected with Physaloptera spp. This is the first recorded finding of stomach worm, i.e. Physaloptera spp. in shrews of Bangladesh. The intermediate host of Physaloptera spp. is cockroach, and S. murinus might be infected by feeding of a cockroach.

Conclusion

These are the first data on the helminths of S. murinus from Bangladesh. Shrews from southeastern parts of Bangladesh had high prevalence rate and susceptibility to parasitic infestation. Two cestodes, three nematodes, and one trematode were identified in these wild shrews. Two of these parasites are of zoonotic significance, indicating the necessary step is crucial in the prevention of the transmission of zoonotic parasites. This study may also contribute to generate knowledge on the understanding of range and helminthic parasitism in house shrew from diverse regions and climatic zones of the world. The important position occupied by these animals in biocoenosis, their distribution, population density, the fact that this species cohabitate with humans, and the limited knowledge of their GI parasites in Bangladesh imply the necessity of further investigation. Studies focused on determining the prevalence of helminths infestation, risk factors for the parasitism, and the geographic distribution of helminths in shrews are needed to understand the helminth burden and guide effective prevention and control measures. Therefore, polymerase chain reaction-based molecular diagnosis and advanced scientific investigations are imperative to understand the helminth diversity and discovery of new helminth species transmission cycles and zoonotic potentials.

Authors’ Contributions

AI and MAH designed and supervised the study; MR, SI, and MNI collected the data and conducted the study. MAH and MM assisted the laboratory experimentation and identification of parasites. MR, SI, JF, and AI were involved in data analysis and interpretation and prepared the draft of the manuscript; MA, MNUC, MMH, MAH, and AI were involved in critical revision of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, contributed, and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University Grants Commission (UGC), HEQEP (Grant No. CP-2180), and USAID Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT project (cooperative agreement number: GHN-A-OO-09-00010-00) for their financial support to conduct the study. We thank Belal Uddin and Abdullah Al Mamun for their contribution to this study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hutterer R. Order Soricomorpha. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2005. pp. 220–311. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aziz M.A. Notes on the status of mammalian fauna of the Lawachara National Park, Bangladesh. Ecoprint An Int. J. Ecol. 2013;18:45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katakweba A.A, Mulungu L.S, Eiseb S.J, Mahlaba T.A.A, Makundi R.H, Massawe A.W, Borremans B, Belmain S.R. Prevalence of hemoparasites, leptospires and coccobacilli with potential for human infection in the blood of rodents and shrews from selected localities in Tanzania, Namibia and Swaziland. Afr. Zool. 2012;47:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veciana M, Chaisiri K, Morand S, Ribas A. Helminths of the Asian house shrew Suncus murinus from Cambodia. Combodian. J. Nat. Hist. 2012;2:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yadav P.D, Vincent M.J, Nichol S.T. Thottapalayam virus is genetically distant to the rodent-borne hantaviruses, consistent with its isolation from the Asian house shrew (Suncus murinus) Virol. J. 2007;4:80. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arai S, Song J.W, Sumibcay L, Bennett S.N, Nerurkar V.R, Parmenter C, Cook J.A, Yates T.L, Yanagihara R. Hantavirus in northern short-tailed shrew, United States. Emer. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:1420. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.070484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh B, Gajadhar A. Role of India's wildlife in the emergence and re-emergence of zoonotic pathogens, risk factors and public health implications. Act. Trop. 2014;138:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kijlstra A, Meerburg B, Cornelissen J, De Craeye S, Vereijken P, Jongert E. The role of rodents and shrews in the transmission of Toxoplasma gondii to pigs. Vet. Parasitol. 2008;156:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gibson D.I, Bray R.A, Hunt D, Georgiev B.B, Scholz T, Harris P.D, Bakke T.A, Pojmanska T, Niewiadomska K, Kostadinova A. Fauna Europaea: Helminths (animal parasitic) Biodivers. Data. J. 2014;2:1060. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roots C.D. Morphological and Ecological Studies on Helminth Parasites of British Shrews. Morphological and Ecological Studies on Helminth Parasites of British Shrews. 1992. [Last accessed on 16-04-2018]. Available from: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19940802626 .

- 11.Zain S.N.M, Behnke J.M, Lewis J.W. Helminth communities from two urban rat populations in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Parasites. Vectors. 2012;5:47. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pakdeenarong N, Siribat P, Chaisiri K, Douangboupha B, Ribas A, Chaval Y, Herbreteau V, Morand S. Helminth communities in murid rodents from southern and northern localities in Lao PDR: The role of habitat and season. J. Helminthol. 2014;8:302–309. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X13000187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fryxell J.M, Sinclair A.R, Caughley G. Wildlife Ecology, Conservation, and Management. United States: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poulin R, Morand S. Parasite Biodiversity. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres-Acosta J, Sandoval-Castro C, Hoste H, Aguilar-Caballero A, Cámara-Sarmiento R, Alonso-Díaz M. Nutritional manipulation of sheep and goats for the control of gastrointestinal nematodes under hot humid and subhumid tropical conditions. Small Rumin. Res. 2012;103:28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patz J.A, Daszak P, Tabor G.M, Aguirre A.A, Pearl M, Epstein J, Wolfe N.D, Kilpatrick A.M, Foufopoulos J, Molyneux D. Unhealthy landscapes: Policy recommendations on land use change and infectious disease emergence. Environ. Health Persp. 2004;112:1092. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendes L, Piersma T, Lecoq M, Spaans B.E, Ricklefs R. Disease limited distributions? Contrasts in the prevalence of avian malaria in shorebird species using marine and freshwater habitats. Oikos. 2005;109:396–404. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillespie T.R. Noninvasive assessment of gastrointestinal parasite infections in free-ranging primates. Int. J. Primatol. 2006;27:1129. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tung K.C, Hsiao F.C, Yang C.H, Chou C.C, Lee W.M, Wang K.S, Lai C.H. Surveillance of endoparasitic infections and the first report of Physaloptera spp. and Sarcocystis spp. in farm rodents and shrews in central Taiwan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009;71:43–47. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singla N, Singla L, Gupta K, Sood N. Pathological alterations in natural cases of Capillaria hepatica infection alone and in concurrence with cysticercus fasciolaris in Bandicota bengalensis. J. Parasit. Dis. 2013;37:16–20. doi: 10.1007/s12639-012-0121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raj S, Ghazali S.M, Hock L.K. Endo-parasite fauna of rodents caught in five wet markets in Kuala Lumpur and its potential zoonotic implications. Trop. Biomed. 2009;26:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbreteau V, Jittapalapong S, Rerkamnuaychoke W, Chaval Y, Cosson J.F, Morand S. In: Protocols for Field and Laboratory Rodent Studies. Jittapalapong S, Rerkamnuaychoke W, Chaval Y, Cosson J.F, Morand S, editors. Bangkok, Thailand: Kasetsart University; 2011. pp. 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tung K.C, Hsiao F.C, Wang K.S, Yang C.H, Lai C.H. Study of the endoparasitic fauna of commensal rats and shrews caught in traditional wet markets in Taichung City, Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2013;46:85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Association A.V.M. AVMA Guidelines on Euthanasia. 2007. [Last accessed on 16-04-2018]. Available from: http://www.avma.org/issues/animal_welfare/euthanasia.pdf .

- 25.Payne J, Francis C.M, Phillipps K. Field Guide to the Mammals of Borneo. Kuala Lumpur: Sabah Society; World Wildlife Fund Malaysia; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shafiyyah C.S, Jamaiah I, Rohela M, Lau Y, Aminah F.S. Prevalence of intestinal and blood parasites among wild rats in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Trop. Biomed. 2012;29:544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foreyt W.J. Veterinary Parasitology Reference Manual. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sloss M.W, Kemp R.L. Veterinary Clinical Parasitology. USA: Iowa State University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Opara M.N, Fagbemi B.O. Occurrence and prevalence of gastrointestinal helminthes in the wild grasscutter (Thryonomys swinderianus, Temminck) from Southeast Nigeria. Life Sci. J. 2008;5:50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spellerberg I.F, Fedor P.J. A tribute to Claude Shannon (1916–2001) and a plea for more rigorous use of species richness, species diversity and the 'Shannon–Wiener'Index. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003;12:177–179. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mbora D.N, McPeek M.A. Host density and human activities mediate increased parasite prevalence and richness in primates threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation. J. Ani. Ecol. 2009;78:210–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hussain S, Ram M.S, Kumar A, Shivaji S, Umapathy G. Human presence increases parasitic load in endangered lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) in its fragmented rainforest habitats in southern India. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dussex N, Broquet T, Yearsley J.M. Contrasting dispersal inference methods for the greater white-toothed shrew. J. Wildl. Manage. 2016;80:812–823. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simões R, Luque J, Gentile R, Rosa M, Costa-Neto S, Maldonado A. Biotic and abiotic effects on the intestinal helminth community of the brown rat Rattus norvegicus from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J. Helminthol. 2016;90(1):21–27. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X14000704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diseases C.O.o.t.N.S.o.t.I.H.P. A national survey on current status of the important parasitic diseases in human population. Zhongguo ji sheng chong xue yu ji sheng chong bing za zhi. Chinese J. Parasitol. Parasitic Dis. 2005;23:332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watts N.S, Pajuelo M, Clark T, Loader M-CI, Verastegui M.R, Sterling C, Friedland J.S, Garcia H.H, Gilma R.H. Taenia solium infection in Peru: a collaboration between Peace Corps Volunteers and researchers in a community based study. PloS One. 2014;9(12):e113239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sah K, Poudel I, Subedi S, Singh D.K, Cocker J, Kushwaha P, Colston A, Donadeu M, Lightowlers M.W. A hyperendemic focus of Taenia solium transmission in the Banke District of Nepal. Acta Trop. 2017;176:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Devleesschauwer B, Aryal A, Joshi D.D, Rijal S, Sherchand J.B, Praet N, Speybroeck N, Duchateau L, Vercruysse J, Dorny P. Epidemiology of Taenia solium in Nepal: is it influenced by the social characteristics of the population and the presence of Taenia asiatica ? Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2012;17:1019–1022. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiwanitkit V. Overview of Hymenolepis diminuta infection among Thai patients. Medscape Gen. Med. 2004;6(2):7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaisiri K, Chaeychomsri W, Siruntawineti J, Ribas A, Herbreteau V, Morand S. Gastrointestinal helminth infections in Asian house rats (Rattus tanezumi) from northern and northeastern Thailand. J. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2010;33:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binkienė R. Helminth fauna of shrews (Sorex spp.) in Lithuania. Acta Zool. Lit. 2006;16:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spickett A, Junker K, Krasnov B.R, Haukisalmi V, Matthee S. Community structure of helminth parasites in two closely related South African rodents differing in sociality and spatial behaviour. Parasitol. Res. 2017;116:2299–2312. doi: 10.1007/s00436-017-5538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nunn C, Altizer S.M. Infectious Diseases in Primates: Behavior, Ecology and Evolution. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Traub R.J, Robertson I.D, Irwin P, Mencke N, Thompson R.A. The role of dogs in transmission of gastrointestinal parasites in a remote tea-growing community in northeastern India. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2002;67:539–545. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wood C.L, Johnson P.T. A world without parasites: exploring the hidden ecology of infection. Frontiers Ecol. Environm. 2015;13:425–434. doi: 10.1890/140368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coop R, Holmes P. Nutrition and parasite interaction. Int. J. Parasitol. 1996;26:951–962. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(96)80070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bordes F, Morand S. The impact of multiple infections on wild animal hosts: A review. Infect. Ecol. Epidemiol. 2011;1:7346. doi: 10.3402/iee.v1i0.7346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warwick C, Arena P, Steedman C, Jessop M. A review of captive exotic animal-linked zoonoses. J. Environ. Health Res. 2012;12:9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Souza J.G, Garcia J.S, Gomes A.P.N, Machado-Silva J.R, Maldonado J.A. Comparative pattern of growth and development of Echinostoma paraensei (Digenea : Echinostomatidae) in hamster and Wistar rat using light and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Experim. Parasitol. 2017;183:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]