Abstract

In this article, we describe and evaluate body mapping as (a) an arts-based activity within Fostering Open eXpression Among Youth (FOXY), an educational intervention targeting Northwest Territories (NWT) youth, and (b) a research data collection tool. Data included individual interviews with 41 female participants (aged 13–17 years) who attended FOXY body mapping workshops in six communities in 2013, field notes taken by the researcher during the workshops and interviews, and written reflections from seven FOXY facilitators on the body mapping process (from 2013 to 2016). Thematic analysis explored the utility of body mapping using a developmental evaluation methodology. The results show body mapping is an intervention tool that supports and encourages participant self-reflection, introspection, personal connectedness, and processing difficult emotions. Body mapping is also a data collection catalyst that enables trust and youth voice in research, reduces verbal communication barriers, and facilitates the collection of rich data regarding personal experiences.

Keywords: arts-based research methods, sexual health, body mapping, Indigenous populations, intervention research, youth, qualitative methods, developmental evaluation, Northwest Territories

The sexual health of Northwest Territories (NWT) youth is a serious public health concern, as rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pregnancies among adolescents are extremely high (Lys et al., 2016; McKay, 2012; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015). Researchers must better understand the determinants underlying these statistics to ensure that interventions best meet the needs of NWT youth and other Northern populations. Previous research focused on the surveillance of STIs among youth in the NWT or the factors that influenced STI transmission (Brassard et al., 2012; Edwards, Mitchell, Gibson, Martin, & Zoe-Martin, 2008; Gibson, Martin, Zoe, Edwards, & Gibson, 2008; Logie, Lys, Okumu, & Leone, 2017; Lys, 2009; Lys & Reading, 2012; Steenbeek, 2004; Steenbeek, Tyndall, Rothenberg, & Sheps, 2006). However, few studies have evaluated the impact of interventions targeting the determinants of NWT youth sexual health (Edwards, Gibson, Martin, Mitchell, & Andersson, 2011; Fanian, Young, Mantla, Daniels, & Chatwood, 2015).

Intervention sexual health research among other Northern populations is similarly scarce. Only a handful of studies have focused on the evaluation of sexual health interventions among Northern youth outside of the NWT (Hohman-Billmeier, Nye, & Martin, 2016; Markham et al., 2016; Rink, Gesink Law, Montgomery-Andersen, Mulvad, & Koch, 2009; Rink, Montgomery-Andersen, & Anastario, 2015; Shegog et al., 2016). One challenge with interventions involving youth can be eliciting deeper meaningful conversation about sexual health issues that participants may regard as potentially stigmatizing or uncomfortable to discuss (Chenhall, Davison, Fitz, Pearse, & Senior, 2013). The arts-based method of body mapping is a promising modality for generating conversations with Northern youth about difficult subject matter as this approach has been successful for research involving adults living with HIV (Brett-MacLean, 2009; Devine, 2008; MacGregor, 2009; MacGregor & Mills, 2011; Nostlinger, Loos, & Verhoest, 2015; Orchard, Smith, Michelow, Salters, & Hogg, 2014; Solomon, 2002; Vasquez, 2004), young motherhood (Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, Jernigan, & Krause, 2016), diagnoses of subfertility (Hughes & Mann de Silva, 2011), and to explore sexual health and sexual decision-making among young adults in Australia (Chenhall et al., 2013; Senior, Helmer, Chenhall, & Burbank, 2014). Although studies provide insights on sexual health intervention research and the collection of rich research data from difficult-to-reach populations such as youth, the use and evaluation of body mapping as a sexual health intervention and data collection method has not yet been applied with youth in a remote northern Arctic setting. This study describes and evaluates body mapping as an approach for educational intervention and research data collection with this population of youth.

Background

Sexual health intervention research with children and youth often has significant challenges that can include difficulties engaging young people in research, real or perceived power differentials between youth participants and researchers (MacDonald et al., 2011; Mitchell, 2006), issues establishing trusting participant–researcher relationships that encourage young individuals to openly share their experiences, and the assumption that young people may not be reliable sources for self-reported data (Crivello, Camfield, & Woodhead, 2009). Youth may benefit from research methods that engage them, accommodate lower comprehension and literacy than adults, provide safety of expression, and support sharing of experiences even when discussing potentially uncomfortable topics like sexual health (Chenhall et al., 2013). Surveys often capture very specific sexual health information, and are typically not designed to provide an in-depth exploration of the social determinants that can influence decision-making about sexual health.

Arts-based research methods have been successful at collecting data from youth regarding general health issues (Chenhall et al., 2013), poverty (Crivello et al., 2009), community health (Wang, 2006), the effects of child labor (Gamlin, 2011), and sexual risk-taking (MacDonald et al., 2011). Arts-based research is defined by the presence of certain aesthetic qualities or design elements that permeate the research inquiry (Barone & Eisner, 2006) as well as the production, interpretation, or communication of knowledge (Vaughan, 2005). Arts-based research spans a broad spectrum of activities, from research that is generated as art is created to research for which the arts are a form of data representation (Vaughan, 2005). Common arts-based intervention approaches in the health literature include visual methods, literary methods, and performance methods (Fraser & al Sayah, 2011).

Visual arts-based methodologies are relatively new to health intervention research and their use by social scientists has increased over the last few decades (Gauntlett & Holzwarth, 2006; Weber, 2008). Visual methodologies can help participants pay attention to phenomena in new ways (Eisner, 2002), are likely to be memorable and accessible for most audiences (including those with low levels of literacy; Coad, 2007), can enhance understanding of experiences that are difficult to explain using words, and facilitate conversation about topics that are challenging to discuss, stigmatized, or taboo (Crivello et al., 2009; Devine, 2008; Mitchell, 2006; Morgan, McInerney, Rumbold, & Liamputtong, 2009). Visual methodologies can generate knowledge in research regarding experiences (Morgan et al., 2009), attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs about sexual health issues (Stuart, 2006).

Visual methodologies are also a potentially effective route for individual empowerment in research. Young people can make their knowledge and concerns visible to researchers (who are typically adults), even if they do not have the vocabulary or depth of understanding to convey their knowledge and experience in words. The exchange with the researcher/adult may help the youth participant process their experiences and put words to their thoughts and feelings. In addition, young people can utilize visual methodologies to help identify and solve issues in their communities (Mitchell, 2006). Visual methods commonly used with younger participants in sexual health research include photovoice (Flicker, Savan, Kolenda, & Mildenberger, 2008; Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, Lowe, DiFulvio, & Del Toro-Mejias, 2016; Wang, 2006; Woods-Jaeger et al., 2013), drawing (Morgan et al., 2009; Stuart, 2006), collage (Butler-Kisber, 2010), and digital storytelling (DeGennaro, 2008; Dreon, Kerper, & Landis, 2011).

Body mapping is a newer visual research method that has been used as a sexual health intervention (Brett-MacLean, 2009; Chenhall et al., 2013; Devine, 2008; Gastaldo, Magalhaes, Carrasco, & Davy, 2012; MacGregor, 2009; Solomon, 2002). Body mapping involves the process of creating body maps using drawing, painting, or other media to visually represent aspects of individual’s lives, their bodies, and the world they live in (Gastaldo et al., 2012). Body mapping originated as an alternative to standard counseling for South African women living with HIV and AIDS as part of The Memory Box Project (Vasquez, 2004), which was a method for these women to record their personal stories and experiences. Variations of body mapping have since been used as an art therapy technique in several psychotherapy interventions for treatment of illnesses, such as among women struggling with mental health issues caused by a diagnosis of subfertility (Hughes & Mann de Silva, 2011) and patients undergoing hemodialysis for renal disease (Ludlow, 2014). Although the popularity of body mapping appears to be growing and several studies attest to its use as an art therapy technique to treat illness, limited literature explores body mapping as a research tool with youth participants, and body mapping has not been used as a research method with youth in Northern Canada previously based on published literature.

Method

Study Setting

There are 41,462 people living in the NWT, with approximately half of these individuals living in the capital city of Yellowknife (Statistics Canada, 2012). Half of the NWT’s population (50%) are Indigenous, including Dene, Inuit, and Métis; 44% are Caucasian; and 5.5% are visible minorities. A lower proportion of Indigenous peoples live in Yellowknife (22%) compared with regional centers (50% on average) and smaller communities (approximately 80%–90%). The NWT has a young population; 33% of the total population is under 19 years of age (Statistics Canada, 2010). The NWT has a low population density concentrated mostly in geographically remote and isolated communities (33 communities in 1,171,918 square kilometers). Several communities are accessible only by ice road in the winter, or by boat or plane in the summer, as the permanent road system is limited.

An analysis of sexual health in the NWT indicates that sexual health is a serious public health concern for Northern youth (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015). Many STIs are highest among young people aged 15 to 24 years (Government of the Northwest Territories, 2011). Adolescent pregnancy rates in the NWT have steadily decreased since the early 1990s (Government of the Northwest Territories, 2011). However, the NWT continues to report a pregnancy rate (40.0 per 1,000 females aged 15–19 years) that is higher than both the Canadian rate (28.2 per 1,000 female youth) and the national low in Prince Edward Island (14.9 per 1,000 female youth; McKay, 2012).

The FOXY (Fostering Open eXpression Among Youth) Research Project

An arts-based sexual health intervention called FOXY was developed in 2012 by the lead researcher and other lifelong Northerners (including the meaningful involvement of Northern youth; Lys et al., 2016). FOXY is a nonprofit organization that utilizes a peer education model and employs adolescent peer leaders to cofacilitate workshops with adult facilitators. In its first 5 years, FOXY (which is ongoing) provided sexual health education to more than 1,700 young women through daylong workshops held in 22 schools across the NWT, and educated an additional 150 young women through 9-day Peer Leader Retreats held on the land. The FOXY school workshops focus on both visual arts (body mapping) and performance arts as a means to facilitate discussion and education about sexual health (see Call OUT BOX: “A Typical FOXY Workshop”).

A Typical FOXY Workshop

Activities in the standard schedule for a 1-day FOXY workshop include the following (Lys et al., 2016):

Birds and the Bees & Student-Led Sex Ed: Participants work together in groups to create visual word maps and lessons related to sexual health topics, and then co-teach these lessons to their peers with the help of FOXY staff peer leaders.

Question Box: Facilitated group discussion that provides key sexual health education messaging to participants.

Myth versus Truth: Participants are presented with statements regarding sexual health and a group discussion is facilitated regarding whether these statements are true or false.

Healthy Relationship Charades: Nonverbal role-playing is used to promote dialogue and facilitate understanding on topics related to sexual health and healthy relationships.

Role-Playing: Participants perform skits to determine realistic and healthy outcomes for common sexual health and relationship scenarios that adolescents encounter.

Body Mapping: Participants create a life-sized image of their body and personality, and tell stories about their experiences of the world, their lives, and their bodies through visual representation.

Researcher Reflexivity

The lead researcher is as an Indigenous woman and lifelong resident of the NWT, and was employed as a community-based researcher at an NWT-based research institute during data collection. The researcher holds an MA in Health Promotion and completed this research project as a requirement for her PhD in Public Health. Her extensive personal and professional involvement with her home territory enabled the development of strong partnerships that helped facilitate this research project. The lead researcher actively participated as a co-facilitator of all body mapping workshops, which is in line with principles of developmental evaluation and community-based participatory research (Castleden, Sloan Morgan, & Lamb, 2012; Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998; Lightfoot, Strasser, Maar, & Jacklin, 2008). The researcher discussed personal goals for the research (e.g., completion of her PhD work) and personal reasons for doing the research (e.g., a desire for culturally relevant and engaging sexual health education) with participants during the informed consent process.

Study Design

This developmental evaluation (Patton, 2011) study uses qualitative methods to describe and evaluate body mapping as an approach for educational intervention and research data collection with youth.

Methodological Framework

The evaluation of the utility of the body mapping component of FOXY uses a developmental evaluation methodology (Patton, 2011), which is particularly suited for dynamic pilot projects (like FOXY) that exist in complex environments. Developmental evaluation recognizes that not all problems are bounded, have optimal solutions, or occur within stable parameters, and instead appreciates that innovative programs often occur within dynamic, complex systems (Fagen et al., 2011; Patton, 2011). Developmental evaluation aims to produce context-specific understandings that inform ongoing innovation, supports changes in direction based on feedback and emerging data, positions the researcher as an integrated member of the collaborative project team, and allows the researcher to design the study to capture system dynamics, interdependence, and emerging interconnections through the data (Gamble, 2008). Developmental evaluation is best suited for projects, like FOXY, that focus on innovation and exploration of solutions to problems as core values; use an iterative loop of idea formation, focus testing, and program redevelopment based on results; and where there is a degree of uncertainty about the path to move forward for the program in the future (Patton, 2011). Summative developmental evaluation used in this study focused on the utility of body mapping to determine whether the activity has merit, meets the needs of participants, and achieves desired outcomes as an educational intervention and tool for data collection (Patton, 2011).

Participants

From October 1 to December 8, 2013, FOXY was delivered to 57 female students from schools in six NWT communities (Fort Providence, Fort Smith, Hay River, Inuvik, Norman Wells, and Yellowknife) and 41 of these attendees chose to participate in this study. These communities were selected due to existing professional relationships with the researcher and interest to participate from school administration. These communities represented all five regions of the NWT (Beaufort Delta, Dehcho, North Slave, Sahtu, South Slave) and ranged in population from approximately 700 to 20,000 people.

Purposive sampling (Creswell, 2007) was conducted by community contacts (e.g., teachers, counselors, administrators) who selected seed participants from community schools. Seed participants were invited due to their interest in the arts or because the community contact believed they would benefit from the workshop content. Seed participants then used word of mouth to invite their friends and develop a snowball sample (Tracy, 2013). This sampling strategy is both appropriate and necessary in small Northern communities where preexisting relationships have a major influence on decision-making, especially for participation in new pilot programs or research involving researchers who are not from the community. Unconventional recruitment and sampling strategies built on relationships among participants are common practice for community-based research in small Northern communities (Corosky & Blystad, 2016; Gesink et al., 2012; Rand, 2016).

A subset of 41 young women ranging in age from 13 to 18 years old (14 years on average), and who had attended one 8-hour FOXY workshop each, opted to participate in this study. Sixteen of the 57 FOXY workshop attendees chose not to participate due to disinterest in the research process, scheduling conflicts for interviews, or other unknown reasons. Participants were notified during the informed consent process that all data would remain anonymous and confidential unless there was a reportable disclosure (e.g., child abuse) and written consent was obtained from all study participants. Letters that provided detail on the research project and included a reverse consent form (that asked parents/guardians to return the signed form if they did not want their ward to participate in the study) were sent to parents/guardians.

The researcher also invited all adult and adolescent (peer leader) staff who had facilitated body mapping to reflect on their experiences leading the intervention, including what they learned about youth and their perceptions of how body mapping affected youth. Seven of the eight female peer leaders and facilitators shared their written reflections on body mapping with the lead researcher, which they documented between 2013 and 2016.

Data Collection

The researcher triangulated four sources of data to evaluate the effectiveness of body mapping as an intervention and data collection tool for research. Specifically, the lead researcher utilized the following: body maps and semistructured interviews regarding these body maps with 41 youth participants, written reflections that ranged from a paragraph to several pages in length from seven FOXY peer leaders/facilitators regarding their observations of the utility and effectiveness of body mapping, and descriptive and reflective field notes taken by the lead researcher during FOXY workshops. Descriptive field notes detailed what the lead researcher saw, heard, and experienced, and reflective field notes further clarified and built on the descriptive field notes to reflect on what they learned during their observations (Williams, 2016). Fieldwork also included active participation in workshop activities to build trust with participants, which led to informal conversations that provided the researcher with additional insights about the youth’s experiences with body mapping, such as their depth of engagement with the activity.

Body Map Visualization Prompts

The eight visualizations used in this body mapping study challenge the participants to focus on the following:

The resources that support you.

Where you come from.

Your future dreams and goals.

The life path that you intend to take from your beginnings to your future.

The content and quality of your sexual health education.

Body cues that tell you that you are in an uncomfortable situation.

Body cues that tell you that you are in a comfortable situation.

A power symbol that makes you feel strong and most like yourself.

Youth participants completed individual body maps during the FOXY workshop via a series of eight guided visualizations that were read to them by trained facilitators. These visualizations were modified from the body mapping facilitator manuals by Solomon (Solomon, 2002) and Gastaldo et al. (Gastaldo et al., 2012), and added to during the initial piloting of FOXY workshops (see CALL OUT BOX: “Body Map Visualization Prompts”).

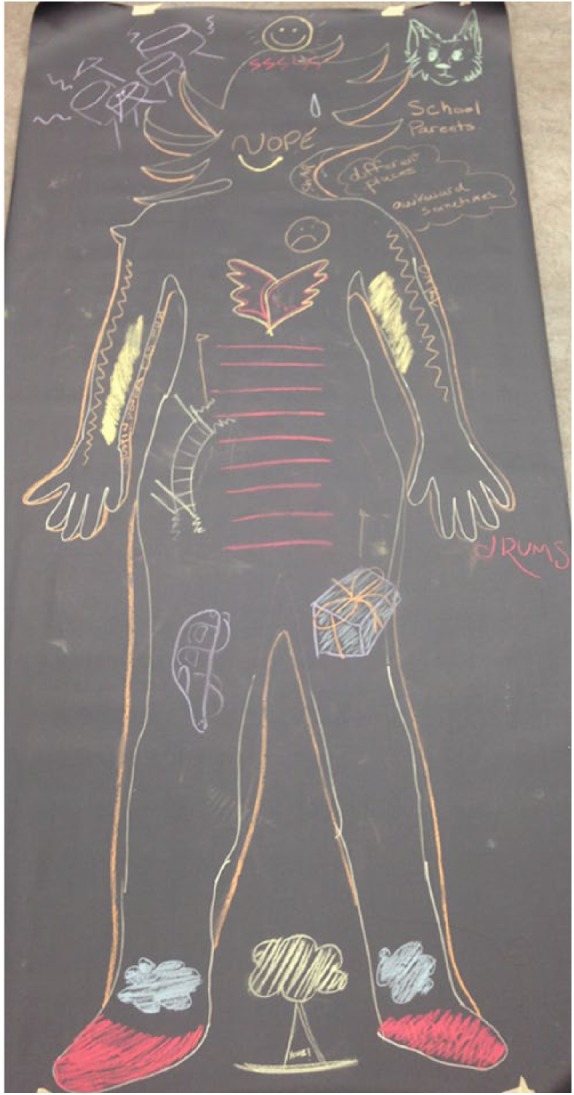

Each participant’s body map was displayed for their individual interview so the participant could explain their artwork and used as a catalyst for in-depth discussion with the researcher about the social–ecological factors that influence sexual and mental health such as culture, connection to the land, religious beliefs, artistic expression, and social supports (these results will be discussed in detail in a future article). Table 1 provides an abridged example of how data were extracted from the body map shown in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Example of Data Extracted From the Body Map Shown in Figure 1.

| Interview Prompt | Drawing (Location) | Participant Response | Data Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explain what you drew to represent your future | Smiley face inside sun (top middle—above head) | “That is just being happier than I was ever, because I’m getting happier, like I’m happy right now . . . Dad suggested that it had something to do with the change in weather when it turns from summer to winter, but I was depressed last year. I personally told the counselor here that I was . . . doing stuff. And so then she got me help at the health center that same day, and I met mom and she was really upset. Then I had to go to counseling.” | Social supports, mental health concerns, mental health supports, relationships with parents |

| Explain the drawing to represent when your body is telling you no | Tear drop and red wavy lines (top middle—on face) | “The red lines resemble stuff that’s already happened to me. I am a very emotional person because when I get frustrated or upset I tend to cry. I can’t seem to get my point across when I’m upset, and then I get so upset that I start to cry . . . I’m angry first and then sad. And that’s where those squigglies come from, because I’m like oh, I need to release some energy. Usually I go upstairs and blast music though . . . Usually me and my mom have the bad fights because we never really see eye to eye at all. We usually fight a lot.” | Coping strategies, relationships with parents |

Figure 1.

Sample body map.

At the start of each interview, the lead researcher instructed participants to reflect only on their experiences with body mapping and not on other components of the FOXY program. Participants were directed to reflect on the meaning, utility, strengths, and weaknesses of body mapping. Examples of questions included the following: “What was the most useful thing you learned today?”; “Will you use what you learned today from body mapping in your real life? How?”; “What was your least favorite part [of body mapping]?”; and “Did any part of today upset you and why?” Interviews lasted from 27 to 67 minutes, were digitally recorded, and occurred with the lead researcher in a private classroom in the schools within 3 days of completing the FOXY intervention. Participants had the option to take their body maps home after it was photographed. Participants were provided with a list of local, territorial, and national mental and sexual health resources at the conclusion of the interview. The lead researcher also notified all participants of the counselors available in each community after connecting with these counselors to ensure they were available if required.

Data Analysis

Data analysis began by transcribing recordings of participant interviews verbatim and then removing any identifying information. Interviews and facilitator/peer leader reflections were analyzed using a thematic analysis process (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to describe and evaluate body mapping’s effectiveness as a method of data collection and intervention with youth. Thematic analysis is often used for qualitative studies with a foundation in health, and is well suited for this summative developmental evaluation methodological framework that focuses on the utility of body mapping while recognizing the value of context-specific understandings of complex systems and aims to capture emerging interconnections in the data. ATLAS.ti Mac software (Version 1.6.0; ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development, 2016) was used to organize the data and assist with analysis.

Preliminary codes began to emerge and crystallize during data collection and were captured in the field notes. Codes continued to develop during rereading and immersion in the transcripts. Codes were collated into potential themes when rereading the transcripts. Extracts relevant to each theme were gathered, and a thematic map of the analysis was created to portray how themes existed in relation to the coded extracts. Finally, themes were defined and the overall structure of the analysis was refined to generate clear definitions and names for each of the themes. The researcher also coded and analyzed the descriptive and reflective field notes and written reflections from peer leaders/facilitators for themes using the same process, and found thick description within these data sources that supported the findings as they are presented.

The researchers ensured rigor in the data collection and analyses by pilot testing interview guides with youth participants, diversifying data collection to include multiple perspectives, triangulating results of the analyses, and member-checking interview transcripts with youth participants to confirm accuracy and clarification of meanings during the pilot testing of the semistructured interview guide (Birt, Scott, Cavers, Campbell, & Walter, 2016; Creswell, 2007). Six youth participants engaged in the member-checking process and provided comments on their individual transcripts to help refine the interview guide during pilot testing to ensure comprehension, and flow, order, and utility of prompts. Changes in interview protocols during a study often reflect a more in-depth understanding of the research topic and setting, and increasing validity of findings (Borkan, 1999). However, member checking with youth participants was not successful beyond the pilot testing phase. The lead researcher offered member checking as an option to all participants during data collection, though only a few youth participants indicated that they were interested and none responded to email requests from the researcher for member checking. However, all seven facilitators contributed to the member-checking process by reviewing preliminary drafts of analyses and discussing findings with the lead researcher.

Results are reported using the 32-item checklist of consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007).

Ethics Approval

This research project received ethical approval (Protocol No. 29038) from the University of Toronto HIV Community-Based Research Ethics Board and was licensed by NWT Research License No. 15292.

Results

All but four of the 41 youth participants lived in the NWT for most, if not all, of their lives. The remaining four participants lived in the NWT for a minimum of 2 years. About 90% (n = 37) self-identified as Aboriginal or Indigenous (First Nations, Métis, or Inuit), 44% (n = 18) lived with both of their parents, 26% (n = 11) lived with one parent, 17% (n = 7) lived with other extended family members, 12% (n = 5) lived with foster parents or in a group home at the time of data collection. Thirty participants had never taken a previous FOXY workshop, seven had taken one FOXY workshop previously, and four had taken two or more previous FOXY workshops. FOXY teams returned to communities on average once per school year, and many youth chose to retake workshops each year to refresh their understanding of the content. None of the youth who participated in this study had previously participated in a data collection interview regarding the evaluation of body mapping.

FOXY facilitators ranged in age from 15 to 62 years, and lived in one of two NWT communities, though most were originally from other communities in Northern Canada. Four of the seven facilitators self-identified as Aboriginal or Indigenous peoples. All facilitators had undergone the body mapping process at least once before to create their own personal body maps, which added depth to their knowledge and experience of body mapping.

The evaluation indicated that body mapping was valuable as an educational intervention tool because it facilitated introspection, personal connectedness, the realization of meaning, and processing of emotions for participants. Body mapping was also an effective tool for data collection in research with the youth when combined with individual in-depth interviews. Below we present participants’ body mapping experiences and then reflections of facilitators on the experiences that they have witnessed.

Body Mapping as an Educational Intervention-Facilitating Introspection, Identity Building, Meaning-Making, and Emotional Processing

Participant experiences

Participants described body mapping as a highly effective educational intervention that was well-liked and overwhelmingly perceived as beneficial for themselves and their peers. Many participants felt that body mapping allowed them to feel and express gratitude for who they are as individuals. One participant was excited about these realizations and stated that she felt empowered by the body mapping process: “I won’t take myself for granted and make myself feel lesser than the people around me. I am equal and I matter!” Another participant expressed that during body mapping, she felt a sense of pride in who she was and that she learned through the process: “to stand up for myself. I will stand up, and tell others that I’m me and they can’t change that.”

Participants were able to increase meaning and personal connectedness with themselves, and one participant spoke of how this reflection and introspection led to building positive awareness of herself:

I really like how we did body mapping in the FOXY workshop, because it does get you to understand yourself better and it makes you realize that it’s not all bad and there’s a lot of good in you too. It makes you think more about your personality and the good stuff about yourself, instead of your looks.

Another participant also remarked that body mapping helped participants develop their self-awareness when asked what her favorite part of the workshop was: “Doing the body map—because there’s things that I didn’t know about myself until I actually thought about it.” One participant reflected that body mapping assisted them with defining their background and cultural identity as an Indigenous person: “I figured out where I consider my roots to come from. I learned that I am a strong, independent young Native.”

Body mapping also facilitated the identification and labeling of emotions, and allowed participants to express their thoughts and feelings through art, as one participant stated, “From body mapping, I learned that I am actually a really energetic and happy person, alone or around others.” One component of the body mapping process led participants through a guided visualization to self-identify bodily cues about healthy or unhealthy situations. Many participants recognized the importance of being able to identify these body cues to have the awareness that enables them to make better choices in difficult situations. One participant stated, “Knowing the way my body reacts is helpful. I will pay more attention to the way my body reacts.”

Some participants were also motivated to enact change based on the introspection they underwent during body mapping. Several participants stated that they would make the choice to be more accepting of themselves because of the self-knowledge that they gained through body mapping, such as one participant who declared, “I will be more accepting of myself. I will just be myself, and if someone doesn’t like it then screw them. I won’t be afraid to show people the real me.” Another participant stated that she planned to make changes to be a better person. When asked how she will use what she learned during the body mapping workshop in her life, she said, “I was able to see the good parts about myself and I will be able to make changes to my bad negative parts because of body mapping.”

Participants were given the opportunity to identify an individual power symbol during the body mapping process as part of this emotional processing. Self-identifying these power symbols was an asset-based approach to self-empowerment that was intended to allow participants to concentrate on their individual strengths. One participant stated about her power symbol that “I liked focusing on the positive and learning my strengths.”

Participants confronted aspects of themselves that they may not have considered before, and made sense of difficult, complex issues with themselves and their relationships. For instance, one participant stated that through body mapping she realized: “Even when you feel alone, like all the time, there’s always someone that cares and is there for you.” Although this participant had discussed the complicated relationships that she had with some family members, during the body mapping exercise she explored and recognized the social supports she did have in her life.

Although the majority of participants indicated that they enjoyed the body mapping process, the most common negative reflection was that the process was difficult because of a self-perceived lack of creativity or due to emotional discomfort. For instance, when asked if any part of the FOXY workshop upset her, one participant stated, “Only the body mapping, but I also loved it.” Another participant noted discomfort with the activity and explained, “Introspective stuff is hard.”

Facilitator reflections

Facilitators witnessed the body mapping process and enriched the findings of participants with their own reflections. An adolescent FOXY peer leader who had previously been a workshop participant reflected that body mapping provided a method for self-reflection and introspection that encouraged positive identity building among participants:

Body mapping is such an incredible activity to help the girls connect with themselves and really open up using art. It’s one of the activities in FOXY where a lot of the time almost every participant ends up loving it in the end. By doing body mapping, I think a lot of the girls really do learn new things about themselves in the process.

Facilitators felt that body mapping created a safe and enabling environment for youth to reflect on and work through their own understandings of who they were. Sometimes this led participants to process experiences of trauma, and some participants indicated to facilitators that they were not previously able to verbalize these topics before creating a body map. One peer leader who had created her first body map at age 17 and then again at age 20 when she was then a survivor of sexual assault reflected,

I think it’s an invaluable facilitation tool to even out the playing field for participants who find naming the source of their pain, trauma, or violence difficult. When I body mapped five months after I had been sexually assaulted, I found that themes about myself had emerged that I hadn’t prepared myself for. As an adult, and as someone who was just following the [guided visualization] script that I had facilitated from multiple times, I didn’t expect that I would “discover” anything about my body. Instead, I realized that I had desperately been trying to ignore my body’s sensations.

One facilitator reflected that some participants were unaware of their personal body cues until prompted to focus on and recognize these cues during the guided visualizations:

My favourite moments from body mapping are when the girls are asked to illustrate their body cues that tell them “yes” and “no.” It’s like they know the answer is in there somewhere, but no one has ever really asked them these questions before. It takes a few minutes to percolate, but when their answers surface, the look of realization and resolution on their faces is undeniable. Some girls are unsure when first asked, but after being led through a hypothetical example it clicks like an “aha!” moment and they begin transposing that idea onto their map with a sort of self-assured satisfaction.

Facilitators and peer leaders were trained in both the body mapping process and how to support participants who may be experiencing distress. Adolescent peer leaders watched during the activity for participants who were less engaged or who struggled with the process to further mediate potential discomfort for participants and to foster engagement. Peer leaders sat with these participants to discuss the guided visualizations, help facilitate self-reflection, and provide encouragement for those who initially felt they were not creative. One facilitator emphasized the value of having adolescent peer leaders cofacilitate the body mapping process with adult facilitators:

Body mapping works because it is arts-based; it is personal; it is guided; it is reflective and goal oriented. However, the key to the whole exercise is the peer leaders who prompt body mapping participants with key questions and support them when the participants need it.

Facilitators reflected that body mapping was a flexible outlet for expression, allowing young people to choose the salient and relevant aspects of their lives to examine the often complex relationships they had with their own bodies and other people, and then to begin to process sometimes difficult emotions when debriefing with FOXY facilitators. One peer leader who identified as queer remarked,

For queer people, our bodies are often criminalized. When we did body mapping, often there was a lot of body shame reflected in the quotes or question marks on various body parts. A lot of queer participants that I have observed have used words to describe taking back their body in quote form—one participant used rap lyrics, another used inspirational quotes—and it was included in their power symbol.

FOXY workshop facilitators led participants through a group-debriefing discussion after participants completed their body maps, where participants were invited to share as much of their body maps with the group as they felt comfortable. These debriefs were an important process for participants as the discussions often helped participants find meaning in their experiences, provided validation, and created shared experience among participants and with the peer leaders and facilitators. One facilitator remarked that the process of body mapping validated participants’ individual life stories as worthwhile and important:

Body mapping allows participants to think about themselves and their lives, and express those feelings in any way they like. It’s empowering that they get to create an image of themselves that highlights only what they want to highlight—they get to take control over their own image and self. Body mapping allows girls to look at their own personal strengths and motivations, and gain a stronger understanding of their own unique capabilities.

Most participants chose to discuss their body map with the group. For participants who did not want to share in a group format, peer leaders approached these individuals to engage them in separate discussions about their body mapping experiences. In a few instances, participants chose not to talk about their body maps and journaled private notes instead as a debriefing exercise.

Body Mapping as a Powerful Catalyst for Data Collection With Youth

Participant experiences

Body mapping was a powerful catalyst for collecting rich data from youth by helping them express themselves both verbally and nonverbally. Participants often appreciated that body mapping helped them to open up and convey who they felt they really were, and this led to the collection of a rich dataset. One participant stated, “My favorite part of the workshop was the body mapping and the freedom of expression. I got to express my personality on paper. It tells how I really feel. I felt like me.”

Data were collected based on the content of body maps that enriched contextual understanding of the societal and community dynamics, interpersonal relationships, and intrapersonal factors that influenced individual health outcomes and resiliency and coping for participants. For instance, visualization during the body mapping activity encouraged participants to focus on the resources they have to help them through difficult situations. One participant found this visualization very helpful and stated, “I didn’t realize how much support I had until I had drawn my support shadow. Writing it all down made me realize that I had a lot of places to turn if I was feeling alone.”

Many participants indicated that they felt prepared for the interview because through body mapping the participant had time to process their thoughts beforehand. For instance, one participant spoke of this internal processing that occurred: “The body mapping was good because it taught us a lot about ourselves. I loved the body mapping, I found out a lot about myself. It brings out your feelings. I never really think about stuff like that and doing body mapping give me the chance to [think].” This internal processing during body mapping likely led to richer data during the interview than asking a question and requiring an immediate response that could have made a youth participant feel pressured and caused them to “shut down” or mentally and emotionally detach.

Facilitator reflections

Facilitators reflected that body mapping was an especially helpful method of data collection for youth who had on previous occasions struggled to use their voice. The lead researcher stated,

Often body mapping interviewees who found it difficult to answer specific questions about their own experiences with sexuality and gender were better able to respond to questions specific to their body maps. They would point to their power symbols and it was far easier to broach the subjects for the interview.

Body mapping also helped the lead researcher develop trust and rapport with youth because the researcher was witness to the creation of all the body maps used during the interviews.

Often, youth felt more comfortable discussing their art before focusing on themselves. One facilitator reflected on her experience with a participant:

One FOXY participant had little to say during the FOXY workshop, but really opened up when asked about her body map. She spoke of her body map at first as though she was describing someone else’s experiences, like she was detached from the art. As time went on, she opened up more and more about her struggles, each time pointing to different sections of her body map. She struggled with so much—sexual assault, the suicide of a close family member, living within the foster care system. She was hurting, yet so resilient. When she got to the part of her body map that discussed her future, she pointed to her body map where she had written “I will lead my community into greatness” and told me how her goal in life was to be the first female Chief of her First Nation. We cried together.

Body maps were the focal points of interviews and enriched the quality of data. The body map was a catalyst that led participants to discuss difficult topics, and helped many youth remember what they wanted to say. One facilitator reflected on her experiences discussing body maps with participants:

Body mapping allows the participants to express their feelings in a safer, more comfortable manner, allowing them to discuss difficult topics without feeling “on the spot,” or like they might say the wrong thing. Opening up the discussion in this way allows facilitators to hone in on details like past trauma and support networks that may get lost with more objective research methods.

Body mapping helped shift power dynamics in the research interviews because there was a focus on youth viewpoints and the concerns that were salient to them (including what they chose to put on their body maps). The interview was semistructured and the body mapping was guided, yet body mapping was a dynamic process as ultimately the participant decided what was important to them by what they drew on their body maps and then what they chose to share with the researcher during the interview. The creator of the body map was an expert in the content that went into the creation of their art and this was widely recognized by the researcher, further balancing power between the participant and researcher.

Discussion

This study explored the utility of body mapping and found that the method had merit, met the needs of the target population, and achieved its desired outcomes as an approach for educational intervention and data collection with youth. Body mapping was enjoyed by participants and led to self-reflection, introspection, identity building, and a greater sense of gratitude and self-empowerment of young women in the NWT. Body mapping helped participants identify and express emotions, which led to a stronger connectedness to the self and acceptance of who they were as individuals. Participants felt more bodily awareness of personal cues to identify risk, which many felt would help them to identify healthy choices in difficult situations in their lives. Participants were able to examine the often complex relationships with the self and others through body mapping. Body mapping focused on personal strengths, resiliency, and supports within individual environments. This asset-based approach helped young people recognize their abilities to cope and helped to ensure safety of participants during the research process.

Many participants felt that body mapping helped to give them a voice, leading to increased personal validation and reinforced self-worth, as their voices became a catalyst for data collection during research interviews. For participants who felt less comfortable immediately sharing their voice, the body mapping process allowed them to focus on the discussion of their art before conversations shifted as they became more relaxed talking about their experiences. Body mapping also allowed many participants to process complex thoughts before their interviews leading to rich data, and further strengthening body mapping’s utility as a method for data collection.

Several of our findings support existing literature for body mapping as an effective educational intervention (Brett-MacLean, 2009; Gubrium & Shafer, 2014; MacGregor, 2009; Maina, Sutankayo, Chorney, & Caine, 2014; Nostlinger et al., 2015) and research data collection tool (Chenhall et al., 2013; Gamlin, 2011; Gastaldo et al., 2012; Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, Jernigan, & Krause, 2016; Hartman, Mandich, Magalhaes, & Orchard, 2011; Hughes & Mann de Silva, 2011; Jaswal & Harpam, 1997; Keith & Brophy, 2004; Ludlow, 2014; Orchard et al., 2014; Senior et al., 2014; Silva-Segovia, 2016), while also contributing to a dearth in body mapping research involving youth from the Canadian Arctic. First, body mapping was a guided but flexible method that allowed participants to choose to focus on content of data that was most important to them (Gubrium & Shafer, 2014; Orchard et al., 2014). This flexibility encouraged participants to draw and then discuss topics during the interview that were most salient to them and led to a wide breadth of information.

Second, body mapping was an asset-based approach (Gastaldo et al., 2012; Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, Jernigan, & Krause, 2016) that encouraged participants to recognize the strengths and resources within themselves and their communities. The asset-based approach regards youth in a positive light and as valuable members of their communities, which can contribute to strengthened self-esteem and personal connectedness.

Third, body mapping was an innovative method that gave voice and validated the lived experiences of participants (Brett-MacLean, 2009; Gamlin, 2011; Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, Jernigan, & Krause, 2016; Jaswal & Harpam, 1997; Ludlow, 2014; Maina et al., 2014; Nostlinger et al., 2015), which is particularly important for young NWT women given the paucity of research among this population. Many youth participants reported feeling enjoyment and positivity about the body mapping research experience, which can lead to stronger engagement with research, trust in the research process, and ultimately strengthen the richness and utility of data (Crivello et al., 2009; Senior et al., 2014).

The researchers identified potential threats to methodological rigor during the design phase of this study and considered safeguards to mediate these concerns (Butler-Kisber, 2010; Creswell, 2007; Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Merriam, 2009). Dependability and confirmability in the data was maintained by using overlapping methods to crystallize multiple sources of data and by carefully documenting all research procedures, data collection methods, and coding processes to establish an audit trail. Credibility, or the accurate representation of participants’ experiences, was ensured through persistent observation and the taking of detailed field notes by the lead researcher; triangulation of multiple sources of data including participant interviews, written reflections by facilitators, and descriptive and reflective field notes; periodic peer debriefing between the researchers and other peers to discuss methodological concerns and interpretations of data; and member checks during pilot testing. As member checking of results was not successful, the researchers recommend engaging with youth to develop a youth-driven member-checking strategy during development of the research design for future studies.

Findings from this study provide insight into how educators and researchers can use body mapping to engage young women in both sexual health interventions and community-based participatory research. The researchers expect the benefits of body mapping, as both an effective intervention and data collection tool, to be directly transferable to other research settings. At the same time, the details of how body mapping is applied should be context-specific. Educators and researchers using body mapping must be mindful to ensure the safety and comfort of participants, especially if there is a reportable disclosure, as some youth can feel uncomfortable with the focus on the self (Chenhall et al., 2013) and others may be triggered if the introspective nature of body mapping brings up experiences of past trauma or painful events (Crawford, 2010; Gastaldo et al., 2012; Hartman et al., 2011). This is known as embodied trauma, which is how bodies experience, feel, and internalize trauma or violence at different levels (Gubrium, Fiddian-Green, Jernigan, & Krause, 2016). About 90% of the participants in this study self-identified as Indigenous peoples; thus, the researchers were mindful of the potential for intergenerational trauma resulting from the impacts of colonization that is common among Indigenous populations (Reading & Wien, 2009). Body mapping facilitators must ensure that youth are ready for the process, remind them that they are not obligated to complete their body map if they are not ready, and make sure that both immediate and longer term resources are in place and accessible. Facilitators should also be well-trained in the body mapping process and how to support participants (Gubrium & Shafer, 2014), and should lead body grounding or relaxation exercises with participants before and after body mapping to help ensure safety (Crawford, 2010).

Potential directions for future research may build on this important qualitative study to develop a comparative study that explores the effects on participants who have completed a qualitative interview only with those who have completed an interview after receiving a body mapping intervention. As one in four participants in this study had completed this body mapping intervention more than once, additional research may also explore repeat exposure to a body mapping intervention and its impact on evaluation. Furthermore, although the utility of body mapping is evident among young female participants in the Canadian North, the uptake and effectiveness of body mapping among young men is currently unknown. Forthcoming research should focus on the development, implementation, and evaluation of a sexual health education intervention for young men that uses body mapping as both a learning tool and a research method.

Acknowledgments

A heartfelt thank you to all the young women and facilitators who shared their experiences for this study. Many others supported the lead researcher and this project through various stages, including Carmen Logie, Gwen Healey, Julie and Kevin Lys, Nancy MacNeill, Kayley Mackay, Hiedi Yardley, Jenn Mason, Jessica Dutton, Shira Taylor, and Remi Gervais.

Author Biographies

Candice Lys, is a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto Dalla Lana School of Public Health and the Co-Founder/Executive Director of FOXY (Fostering Open eXpression among Youth) in Yellowknife.

Dionne Gesink, is an associate professor with the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto. Her research focuses on the social epidemiology of sexual health using mixed methods.

Carol Strike, is a professor at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, and an Affiliate Scientist at the Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital. Her research program aims to improve health services for people who use drugs and other marginalized populations.

June Larkin, is an associate professor, Teaching Stream, Women and Gender Studies University of Toronto. She is coordinator of the Gendering Adolescent AIDS Prevention (GAAP) project, New College, UofT.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The lead author received financial support in the form of bursaries from the Northern Scientific Training Program (Government of Canada), Indspire, and the Aurora Research Institute; a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Vanier Graduate Scholarship; and funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada.

References

- ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development. (2016). ATLAS.ti Mac 1.6.0. Available from http://www.atlasti.com

- Barone T., Eisner E. (2006). Arts-based education research. In Green J. L., Camilli G., Elmore P. B. (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 95–109). Washington, DC: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Birt L., Scott S., Cavers D., Campbell C., Walter F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26, 1802–1811. doi: 10.1177/1049732316654870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkan J. (1999). Immersion/crystallization. In Crabtree B., Miller W. (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (Vol. 2, pp. 179–194). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brassard P., Jiang Y., Severini A., Goleski V., Santos M., Chatwood S., . . . Mao Y. (2012). Factors associated with the human papillomavirus infection among women in the Northwest Territories. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 103(4), e282–e287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brett-MacLean P. (2009). Body mapping: Embodying the self living with HIV/AIDS. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 180, 740–741. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler-Kisber L. (2010). Qualitative inquiry: Thematic, narrative, and arts-informed perspectives. Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Castleden H., Sloan Morgan V., Lamb C. (2012). “I spent the first year drinking tea”: Exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. The Canadian Geographer, 56, 160–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2012.00432.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chenhall R., Davison B., Fitz J., Pearse T., Senior K. (2013). Engaging youth in sexual health research: Refining a “youth friendly” method in the Northern Territory, Australia. Visual Anthropology Review, 29, 123–132. doi: 10.1111/var.12009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coad J. (2007). Using arts-based techniques in engaging children and young people in health care consultations and/or research. Journal of Research in Nursing, 12, 487–497. doi: 10.1177/1744987107081250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corosky G., Blystad A. (2016). Staying healthy “under the sheets”: Inuit youth experiences of access to sexual and reproductive health and rights in Arviat, Nunavut, Canada. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 75, Article 31812. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v75.31812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A. (2010). If “the body keeps score”: Mapping the dissociated body in trauma narrative, intervention, and theory. University of Toronto Quarterly, 79, 702–719. doi: 10.3138/utq.79.2.702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Crivello G., Camfield L., Woodhead M. (2009). How can children tell us about their well-being? Exploring the potential of participatory research approaches within young lives. Social Indicators Research, 90, 51–72. doi: 10.1007/s11205-008-9312-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeGennaro D. (2008). The dialectics informing identity in a urban youth digital storytelling workshop. E-Learning and Digital Media, 5, 429–444. doi: 10.2304/elea.2008.5.4.429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devine C. (2008). The moon, the stars, and a scar: Body mapping stories of women living with HIV/AIDS. Border Crossings, 27, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dreon O., Kerper R. M., Landis J. (2011). Digital storytelling: A tool for teaching and learning in the YouTube generation. Middle School Journal, 42, 4–9. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2011.11461777 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K., Gibson N., Martin J., Mitchell S., Andersson N. (2011). Impact of community-based interventions on condom use in the Tlicho region of the Northwest Territories, Canada. BMC Health Services Research, 112(Suppl. 2), Article S9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-S2-S9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards K., Mitchell S., Gibson N. L., Martin J., Zoe-Martin C. (2008). Community-coordinated research as HIV/AIDS prevention strategy in northern Canadian communities. Pimatisiwin, 6, 111–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner E. W. (2002). Arts and the creation of the mind. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fagen M. C., Redman S. D., Stacks J., Barrett V., Thullen B., Altenor S., Nieger B. L. (2011). Developmental evaluation: Building innovations in complex environments. Health Promotion Practice, 12, 645–650. doi: 10.1177/1524839911412596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanian S., Young S. K., Mantla M., Daniels A., Chatwood S. (2015). Evaluation of the kots’iihtla (“We Light the Fire”) project: Building resiliency and connections through strengths-based creative arts programming for Indigenous youth. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 74, Article 27672. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v74.27672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flicker S., Savan B., Kolenda B., Mildenberger M. (2008). A snapshot of community-based research in Canada: Who? What? Why? How? Health Education Research, 23, 106–114. doi: 10.1093/her/cym007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser K. D., al Sayah F. (2011). Arts-based methods in health research: A systematic review of the literature. Arts & Health, 3, 110–145. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2011.561357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble J. A. (2008). A developmental evaluation primer. Retrieved from http://50.87.232.11/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/wrappingup_evaluateyourproject_resources_developmental_evaluation_primer.pdf

- Gamlin J. B. (2011). “My eyes are red from looking and looking”: Mexican working children’s perspectives of how tobacco labour affects their bodies. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 6, 339–345. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2011.635222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gastaldo D., Magalhaes L., Carrasco C., Davy C. (2012). Body-map storytelling as research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping. Toronto: Creative Commons. [Google Scholar]

- Gauntlett D., Holzwarth P. (2006). Creative and visual methods for exploring identities. Visual Studies, 21, 82–91. doi: 10.1080/14725860600613261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gesink D., Mulvad G., Montgomery-Andersen R., Poppel U., Montgomery-Andersen S., Binzer A., . . . Skov Jensen J. (2012). Mycoplasma genitalium presence, resistance, and epidemiology in Greenland. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 71, Article 18203. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G., Martin J., Zoe J. B., Edwards K., Gibson N. (2008). Setting our minds to it: Community-centered research for health policy development in Northern Canada. Pimatisiwin, 5, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Government of the Northwest Territories. (2011). Northwest Territories Health Status Report. Yellowknife, Canada: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A., Fiddian-Green A., Jernigan K., Krause E. L. (2016). Bodies as evidence: Mapping new terrain for teen pregnancy and parenting. Global Public Health, 11, 618–635. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1143522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A., Fiddian-Green A., Lowe S., DiFulvio G., Del Toro-Mejias L. (2016). Measuring down: Evaluating digital storytelling as a process for narrative health promotion. Qualitative Health Research, 26, 1787–1801. doi: 10.1177/1049732316649353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium A., Shafer M. (2014). Sensual sexuality education with young parenting women. Health Education Research, 29, 649–661. doi: 10.1093/her/cyu001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman L. R., Mandich A., Magalhaes L., Orchard T. (2011). How do we “see” occupations? An examination of visual research methodologies in the study of human occupation. Journal of Occupational Science, 18, 292–305. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2011.610776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman-Billmeier K., Nye M., Martin S. (2016). Conducting rigorous research with subgroups of at-risk youth: Lessons learned from a teen pregnancy prevention project in Alaska. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 75, Article 31776. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v75.31776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes E. G., Mann de Silva A. (2011). A pilot study assessing art therapy as a mental health intervention for subfertile women. Human Reproduction, 26, 611–615. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B. A., Schulz A. J., Parker E. A., Becker A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal S. K., Harpam T. (1997). Getting sensitive information on sensitive issues: Gynaecological morbidity. Health Policy and Planning, 12, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith M. M., Brophy J. T. (2004). Participatory mapping of occupational hazards and disease among asbestos-exposed workers from a foundry and insulation complex in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Health, 10, 144–153. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2004.10.2.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot N., Strasser R., Maar M., Jacklin K. (2008). Challenges and rewards of health research in Northern, rural, and remote communities. Annals of Epidemiology, 18, 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie C., Lys C., Okumu M., Leone C. (2017). Pathways between depression, substance use, and multiple sex partners among Northern and Indigenous young women in the Northwest Territories, Canada: Results from a cross-sectional survey. Sexually Transmitted Infections. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow B. A. (2014). Witnessing: Creating visual research memos about patient experiences of body mapping in a dialysis unit. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 64, A13–A14. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lys C. (2009). Coming of age: How young women in the Northwest Territories understand the barriers and facilitators to positive, empowered, and safer sexual health (Master’s thesis). Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lys C., Logie C., MacNeill N., Loppie C., Dias L., Masching R., Gesink D. (2016). Arts-based HIV and STI prevention intervention with Northern and Indigenous youth in the Northwest Territories: Study protocol for a non-randomised cohort pilot study. BMJ Open, 6(10), Article e012399. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lys C., Reading C. (2012). Coming of age: How young women in the Northwest Territories understand the barriers and facilitators to positive, empowered, and safer sexual health. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 71(1), Article 18957. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald J. A., Gagnon A. J., Mitchell C., Di Meglio G., Rennick J. E., Cox J. (2011). Include them and they will tell you: Learnings from a participatory process with youth. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 1127–1135. doi: 10.1177/1049732311405799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor H. N. (2009). Mapping the body: Tracing the personal and the political dimensions of HIV/AIDS in Khayelitsha, South Africa. Anthropology & Medicine, 16, 85–95. doi: 10.1080/13648470802426326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor H. N., Mills E. (2011). Framing rights and responsibilities: Accounts of women with a history of AIDS activism. BMC Health and Human Rights, 11(Suppl. 3), Article S7. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-11-S3-S7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina G., Sutankayo L., Chorney R., Caine V. A. (2014). Living with and teaching about HIV: Engaging nursing students through body mapping. Nurse Education Today, 34, 643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham C., Craig Rushing S., Jessen C., Gorman G., Torres J., Lambert W., . . . Shegog R. (2016). Internet-based delivery of evidence-based health promotion programs among American Indian and Alaska Native youth: A case study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, Research Protocols, 5(4), e225. doi: 10.2196/resprot.6017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall C., Rossman G. B. (2011). Designing qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McKay A. (2012). Trends in Canadian national and provincial/territorial teen pregnancy rates: 2001-2010. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 21, 161–175. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell L. M. (2006). Child-centered? Thinking critically about children’s drawings as a visual research method. Visual Anthropology Review, 22, 60–73. doi: 10.1525/var.2006.22.1.60 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M., McInerney F., Rumbold J., Liamputtong P. (2009). Drawing the experience of chronic vaginal thrush and complementary and alternative medicine. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 12, 127–146. doi: 10.1080/13645570902752316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nostlinger C., Loos J., Verhoest X. (2015). Coping with HIV in a culture of silence: Results of a body-mapping workshop. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 31, 47–48. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchard T., Smith T., Michelow W., Salters K., Hogg B. (2014). Imagining adherence: Body mapping research with HIV-positive men and women in Canada. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30, 337–338. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (2011). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2015). Report on sexually transmitted infections in Canada: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/sti-its-surv-epi/rep-rap-2012/index-eng.php

- Rand J. R. (2016). Inuit women’s stories of strength: Informing Inuit community-based HIV and STI prevention and sexual health promotion programming. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 75, Article 32135. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v75.32135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reading C. L., Wien F. (2009). Health inequalities and social determinants of aboriginal peoples’ health. Prince George, British Columbia, Canada: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. [Google Scholar]

- Rink E., Gesink Law D., Montgomery-Andersen R., Mulvad G., Koch A. (2009). The practical application of community-based participatory research in Greenland: Initial experiences of the Greenland Sexual Health Study. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 68, 405–413. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v68i4.17370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink E., Montgomery-Andersen R., Anastario M. (2015). The effectiveness of an education intervention to prevent chlamydia infection among Greenlandic youth. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 26, 98–106. doi: 10.1177/0956462414531240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior K., Helmer J., Chenhall R., Burbank V. (2014). “Young clean and safe?” Young people’s perceptions of risk from sexually transmitted infections in regional, rural, and remote Australia. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 16, 453–466. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.888096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shegog R., Craig Rushing S., Gorman G., Jessen C., Torres J., Lane T., . . . Markham C. (2016). NATIVE-It’s your game: Adapting a technology-based sexual health curriculum for American Indian and Alaska Native youth. Journal of Primary Prevention, 38, 27–48. doi: 10.1007/s10935-016-0440-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Segovia J. (2016). The face of a mother deprived of liberty: Imprisonment, guilt, and stigma in the Norte Grande, Chile. Journal of Women and Social Work, 31, 98–111. doi: 10.1177/0886109915608219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J. (2002). Living with X: A body mapping journey in the time of HIV and AIDS (Facilitator’s guide). Johannesburg, South Africa: Regional Psychosocial Support Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2010). 2006 community profiles—Northwest Territories. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2006/dp-pd/prof/92-591/details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=61&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=NorthwestTerritories&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&GeoLevel=PR&GeoCode=61

- Statistics Canada. (2012). Census Profile: 2011 Census (Northwest Territories [Code 61] and Canada [Code 01]). Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=61&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=northwestterritories&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&Custom=&TABID=1

- Steenbeek A. (2004). A holistic approach in preventing sexually transmitted infections among First Nations and Inuit adolescents in Canada. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 22, 254–256. doi: 10.1177/0898010104266714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenbeek A., Tyndall M., Rothenberg R., Sheps S. (2006). Determinants of sexually transmitted infections among Canadian Inuit adolescent populations. Public Health Nursing, 23, 531–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00592.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart J. (2006). “From our frames”: Exploring with teachers the pedagogic possibilities of a visual arts-based approach to HIV and AIDS. Journal of Education, 38, 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19, 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy S. J. (2013). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact. Sussex, England: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez G. (2004). Body perceptions of HIV and AIDS: The memory box project. Retrieved from http://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/19177/Vasquez_Body_perceptions_2004.pdf?sequence=1

- Vaughan K. (2005). Pieced together: Collage as an artist’s method for interdisciplinary research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 4, 27–52. doi: 10.1177/160940690500400103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. (2006). Youth participation in photovoice as a strategy for community change. Journal of Community Practice, 14, 147–161. doi: 10.1300/J125v14n01_09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S. (2008). Visual images in research. In Knowles J. G., Cole A. L. (Eds.), Handbook of the arts in qualitative research (pp. 41-53). Los Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. (2016). Qualitative inquiry in daily life: Exploring qualitative thought. Retrieved from https://qualitativeinquirydailylife.wordpress.com/

- Woods-Jaeger B. A., Sparks A., Turner K., Griffith T., Jackson M., Lightfoot A. (2013). Exploring the social and community context of African American adolescents’ HIV vulnerability. Qualitative Health Research, 23, 1541–1550. doi: 10.1177/1049732313507143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]