Abstract

Objective

To assess the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care natriuretic peptide tests in patients with chronic heart failure, with a focus on the ambulatory care setting.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Data sources

Ovid Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Embase, Health Technology Assessment Database, Science Citation Index, and Conference Proceedings Citation Index until 31 March 2017.

Study selection

Eligible studies evaluated point-of-care natriuretic peptide testing (B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP)) against any relevant reference standard, including echocardiography, clinical examination, or combinations of these, in humans. Studies were excluded if reported data were insufficient to construct 2×2 tables. No language restrictions were applied.

Results

42 publications of 39 individual studies met the inclusion criteria and 40 publications of 37 studies were included in the analysis. Of the 37 studies, 30 evaluated BNP point-of-care testing and seven evaluated NTproBNP testing. 15 studies were done in ambulatory care settings in populations with a low prevalence of chronic heart failure. Five studies were done in primary care. At thresholds >100 pg/mL, the sensitivity of BNP, measured with the point-of-care index device Triage, was generally high and was 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.90 to 0.98) at 100 pg/mL. At thresholds <100 pg/mL, sensitivity ranged from 0.46 to 0.97 and specificity from 0.31 to 0.98. Primary care studies that used NTproBNP testing reported a sensitivity of 0.99 (0.57 to 1.00) and specificity of 0.60 (0.44 to 0.74) at 135 pg/mL. No statistically significant difference in diagnostic accuracy was found between point-of-care BNP and NTproBNP tests.

Conclusions

Given the lack of studies in primary care, the paucity of NTproBNP data, and potential methodological limitations in these studies, large scale trials in primary care are needed to assess the role of point-of-care natriuretic peptide testing and clarify appropriate thresholds to improve care of patients with suspected or chronic heart failure.

Introduction

An estimated 800 000 people in the UK currently have heart failure, with more than 250 000 new cases every year. Incidence increases with age and is highest in adults aged more than 75 years. The aging population and improved survival of people with ischaemic heart disease are likely to lead to a continuing increase in the prevalence of heart failure. Overall, a general practitioner with a patient population of 2000 will care for about 40-50 patients with heart failure and see two or three new cases each year.1

Since heart failure may be reversible with appropriate treatment in the early stages of disease, early diagnosis is important. Considering the low prevalence of heart failure, however, general practitioners are unlikely to have enough experience to identify more subtle signs. Although heart failure is often diagnosed by general practitioners, on the basis of clinical signs, symptoms, and the results of 12 lead electrocardiography, the diagnosis is only confirmed by echocardiography in about one third of cases.2 Cardiologists generally perform better than general practitioners in using electrocardiography to rule out chronic heart failure (CHF); however, electrocardiography is not a reliable test to diagnose CHF because of its non-specific nature.3 4 Therefore, recent guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, and the European Society for Cardiology (ESC) on the initial diagnosis of CHF and referral for echocardiography recommend the use of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) tests in combination with clinical assessment.5 6

BNP is a protein produced by heart muscle cells as a prohormone (proBNP) and released into the cardiovascular system in response to ventricular dilation and pressure overload.7 The prohormone is split by a protease and secreted as the physiologically active C terminal fragment (BNP) and the inactive N terminal fragment (NTproBNP), which has a longer half life than BNP.

No clear consensus exists about the appropriate BNP threshold for diagnosing CHF. The 2016 ESC guidelines recommend an upper limit of normal of 35 pg/mL for BNP and 125 pg/mL for NTproBNP in the non-acute setting to exclude heart failure. In the acute setting, higher values should be used (BNP <100 pg/mL, NTproBNP <300 pg/mL).6 In contrast, NICE suggests a BNP threshold of 100 pg/mL and an NTproBNP threshold of 400 pg/mL for referral of patients with suspected heart failure.5

Traditionally, hospital laboratories have carried out BNP testing, typically taking up to a day to return results. Many laboratories offer slightly quicker turnaround times but point-of-care BNP tests give results within minutes. The use of point-of-care devices in primary care and other ambulatory care settings allows BNP results to be available when acute management decisions are needed. As well as reducing turnaround time, point-of-care testing by general practitioners could lead to a quicker investigation of dyspnoea, more timely referral, earlier initial treatment, and less uncertainty and anxiety for patients. The development of point-of-care natriuretic peptide testing services in community settings is part of a general effort to move care from hospital settings to the community and make more point-of-care tests available for a range of conditions.8 Several point-of-care devices that test for BNP or NTproBNP are available.

Systematic reviews have been done on the role and accuracy of BNP and NTproBNP testing in the diagnosis of CHF3 9 10 11 12 13 14; however, none has focused specifically on the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care testing. We reviewed the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care natriuretic peptide tests in patients with suspected or confirmed CHF, with a focus on ambulatory care settings.

Methods

Search strategy

Our search strategy (see appendix 1 for protocol) was based on a combination of subject headings and terms for heart failure, the two natriuretic peptides, point-of-care testing (including “point-of-care”, “rapid”, “same time”, “immediate”, “bed-side”), and the known point-of-care index devices (“Triage”, “Cardiac Reader”, “Abbott iSTAT”, “RAMP”, “Cobas h232”, “Alere Heart Check”). We searched several electronic databases from inception until 31 March 2017: Ovid Medline (see appendix 2), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Embase, Health Technology Assessment Database, Science Citation Index, and Conference Proceedings Citation Index. To maximise the sensitivity of the search strategy we did not use filters for diagnostic studies. For unpublished trials, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the trials registers on the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. We also used the “related articles” feature in PubMed and searched reference lists of included studies to identify more publications.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (KST, AP, CB; in pairs) screened titles and abstracts of the search results independently, and disagreements were resolved by referral to a third reviewer. Studies of point-of-care BNP and NTproBNP tests were included that reported diagnostic accuracy as an outcome and compared the index test result with that of any relevant reference standard, including echocardiography, clinical examination, or combinations of these. We excluded comparisons of laboratory based reference tests as they compared methods rather than diagnostic accuracy. Both prospective and retrospective case-control and cohort trial studies were included. Although the focus of the review was the ambulatory care setting, we included studies with participants with suspected or confirmed CHF in all settings because what is considered ambulatory care can vary between countries and we wanted to include all studies with relevant populations. We defined ambulatory care as primary, outpatient, or emergency care—all settings where ambulatory patients with heart failure would present—with the aim of investigating the potential use of point-of-care BNP tests in primary care. We imposed no restrictions on study population numbers or language—studies in languages other than English were translated—and study quality was not an exclusion criterion. Letters, narrative reviews, and other non-primary sources were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they did not provide sufficient data to construct a 2×2 table, were based on animals or non-human samples, or presented duplicate data. If two publications had overlapping populations, they were counted as a single study, and we only included both in our study if each provided diagnostic accuracy data at different thresholds. If both only provided data at the same thresholds, we excluded the publication with the smaller population and recorded this as a duplicate study.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers (KT, CB, JV, AP; in pairs) extracted data independently using a predefined data extraction sheet (see appendix 3), cross checked the data, and resolved disagreements by discussion or referral to a third reviewer. If more than one publication with overlapping populations reported diagnostic accuracy data at the same threshold, we only extracted data from the publication with the larger population.

Assessment of methodological quality

Two reviewers (KT, CB, AP, in pairs) independently assessed the quality of included studies and this was cross checked by a third reviewer (JV), using QUADAS-2.15

Data analysis and synthesis

We extracted binary diagnostic accuracy data from all studies and constructed 2×2 tables at all thresholds. To obtain an overview of test accuracy, we produced a receiver operating characteristic plot of sensitivity and specificity estimates for all thresholds for each natriuretic peptide test. In these plots, we split the data by index test and study design. Study design was defined as either case-control or cross sectional/cohort. Case-control studies were those described as such and also studies with selected healthy and unhealthy populations. As the results of case-control studies are susceptible to bias, we excluded these studies from further analysis that split the data by population (prevalence of CHF) and setting. A study population was categorised as having a high (>50%) or low (≤50%) prevalence of CHF. Study setting was grouped as ambulatory (primary, outpatient, or emergency care), mixed outpatient and inpatient, or inpatient only.

For each natriuretic peptide, we produced paired forest plots with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. We grouped data into categories based on the thresholds recommended by NICE5: <100 pg/mL and ≥100 pg/mL for BNP, and <400 pg/mL and ≥400 pg/mL for NTproBNP.

We then analysed ambulatory care settings only and populations with a low prevalence of heart failure to ensure generalisability to primary care patients. To establish adherence to the thresholds recommended in ESC and NICE guidelines, we summarised the thresholds used in the included studies and pooled data at the recommended thresholds, where possible. We also compared the diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NTproBNP tests.

Summary receiver operating characteristic curves and forest plots were plotted using R version 3.4.2 and RevMan version 5.3.

To generate pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity, we applied bivariate meta-analysis methods.16 We used hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic meta-analysis methods to produce summary receiver operating characteristic curves with corresponding 95% confidence regions and prediction regions for cross sectional/cohort studies collectively for BNP and NTproBNP. Where studies reported data at multiple thresholds, as these were overlapping data, we selected the lowest threshold only for each study because this was consistent with our focus on ambulatory rather than inpatient care. The xtmelogit command in STATA SE version 14.2 was used for these analyses, and parameters were entered directly into RevMan to produce Cochrane standardised output.17

We analysed data from studies with laboratory based reference tests separately from data from studies with reference tests based on clinical assessment. We also analysed data based on populations with suspected CHF separately from data based on populations with confirmed CHF.

To assess heterogeneity between studies, we visually inspected the summary receiver operating characteristic curves and forest plots. We also adjusted for possible sources of heterogeneity by adding covariates to the bivariate model and testing with likelihood ratio tests, and we did a subgroup analysis.17 18 Both approaches focused on concerns about patient selection and used QUADAS-2 assessments. A study was classified as having concerns if either the risk of bias or the applicability concerns was assessed as high, or if both were assessed as unclear. For the analysis adjusting for possible sources of heterogeneity we created a binary variable (with or without concerns about patient selection), and for the subgroup analysis we excluded studies with concerns about patient selection from the comparison of the diagnostic accuracy between BNP and NTproBNP.

To assess the robustness of our conclusions in our comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NTproBNP testing, we evaluated the effect of removing outliers for all studies in ambulatory care settings and using a different data pooling method. This was an extension of the bivariate method of Dukic and Gatsonis,19 which permits the inclusion of multiple threshold values for each study. This was done with R, and using simulation we calculated pointwise confidence intervals for sensitivity and specificity at given thresholds. The selected thresholds were those given in the ESC and NICE guidelines.

To test for publication bias, we applied the Deeks’ test,20 where data allowed, although in cases of high heterogeneity, this would result in low power.20 21 22 In reporting our results, the term “accuracy” is often used to refer to diagnostic accuracy.

Patient involvement

Members of a patient and public involvement group were part of the Stakeholder group and Steering Committee of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme grant that funded this study. The patient and public involvement group includes people with heart failure and other lay people. Updates and details about the study were presented to the steering committee while the study was ongoing, and the public members provided feedback. Two members of this group commented on our completed manuscript. No patients nor patient representatives were involved in setting the outcome measures, nor were they directly involved in developing plans for the design or implementation of the study. A one day dissemination event is planned to report the results of all the studies funded by the NIHR programme grant, including this study. Members of the patient and public involvement group will be invited to this event.

Results

Figure 1 summarises the search results and the inclusion and exclusion of studies. We identified 2604 references through database and registry searches, and an additional 17 publications were identified by checking reference lists of retrieved reviews and using the “related articles” function in PubMed. After removing duplicates, we screened 878 records by title and abstract. Of these and the references identified through reference list searches, the full text of 116 records was reviewed, resulting in 42 publications of 39 individual studies that met our inclusion criteria. The references of all 42 publications are given in appendix 4.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of study selection. Two studies were reported by more than one publication

Five of the studies were in a primary care setting (two assessed BNP and three assessed NTproBNP).23 24 25 26 27 Two studies gave data for confirmed CHF cases.28 29 Seven studies had a case-control design, and 32 were cross sectional/cohort studies, 15 of which had populations presenting mainly with dyspnoea, six had populations with several signs and symptoms of CHF, five had populations of echocardiography referrals, two had populations with cardiovascular risk factors, two had populations with stable CHF referred for cardiac rehabilitation, one had a population with acute coronary embolism, and one had a non-cardiac population receiving mechanical ventilation (see supplementary table S1). Most of the included studies were in secondary care settings, the majority in the emergency department (table 1). The prevalence of CHF in the studies in primary care ranged from 19% to 44%. Of the 14 studies in emergency care settings, 11 reported a prevalence of CHF at or below 50%. The reference test in most of the studies was clinical assessment with retrospective review by one doctor or more (usually cardiologists). Some studies used echocardiography alone as the reference test (table 2).

Table 1.

Included studies, study design and setting, and population characteristics

| Studies | Design | No of participants | Prevalence of heart failure (%)* | Setting | Age (years)† | Men (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies included in analysis | ||||||

| Ajuluchukwu 2009 | Case-control | 72 (42 inpatients+30 controls) | 58 - high | Inpatients and controls were staff and escorts, Nigeria | >14 | Not stated |

| Alibay 2005 | Cross sectional/cohort | 160 | 38 - low | Emergency department, France | 80.1 (13.5) | 48 |

| Blondé-Cynober 2011 | Cross sectional/cohort | 64 | 41 - low | Inpatients, France | 84.3 (7.4) | 31 |

| Breathing not properly study: | ||||||

| Maisel 2002 | Cross sectional/cohort | 1586 | 47 - low | Emergency department, International | 64 (17) | 56 |

| Maisel 2003 | Cross sectional/cohort | 1586 | 47 - low | Emergency department, International | 64 (17) | 56 |

| Pahle 2009‡ | Cross sectional/cohort | 1583 (740 elevated blood pressure+843 normal blood pressure) | 47 - low | Emergency department, International | Elevated: 67 (54-78); normal: 64 (49-76) | Elevated: 51.8; normal: 60 |

| Chenevier-Gobeaux 2010 | Cross sectional/cohort | 378 | 30 - low | Emergency department, France | 78 (12) | 50 |

| Dao 2001 | Cross sectional/cohort | 250 | 39 - low | Emergency and urgent care departments, USA | 63 (0.86) | 94 |

| De Vecchis 2016 | Cross sectional/cohort | 111§ | 44 - low | Outpatients, Italy | 58 (47-65) | 65 |

| Dokanish 2004 | Cross sectional/cohort | 122 | 57 - high | Inpatients, USA | 56 (13) | 51 |

| Fischer 2001 | Cross sectional/cohort but similar to case-control | 145 (95 cardiac+50 healthy) | 29 - low | Unclear, Germany | Cardiac: 61.9 (20-60)¶; healthy range: 19-86 | Cardiac: 67.4; healthy: 60 |

| Fuat 2006 | Cross sectional/cohort | 297 | 38 - low | One-stop diagnostic clinics in 2 hospitals and general practices, England | 73.8 (34-94)¶ | 37 |

| Gorissen 2007 | Cross sectional/cohort | 80 | 50 - low | Emergency department, Netherlands | 74 (10) | 55 |

| Gruson 2009 | Cross sectional/cohort | 97 | 20 - low | Emergency department, Belgium | 71 (30-95) | 57 |

| Jungbauer 2012 | Case-control | 222 (151 confirmed+71 healthy) | 16, 24, 22, or 38†† - low | Outpatients and controls were healthy hospital employees, Germany | Confirmed: 62.9 (12.1); healthy: 39.7 (15.1) | Confirmed: 71.5; healthy: 40.8 |

| Knudsen 2004 | Cross sectional/cohort | 155 | 48 - low | Emergency department, Norway | Men: 74 (66-79); women: 78 (71-84) | 44.5 |

| San Diego veterans’ study: | ||||||

| Krishnaswamy 2001 | Cross sectional/cohort | 400 | 63 - high | Outpatients and inpatients, USA | 65.7 (12.2) | 96 |

| Lubien 2002 | Cross sectional/cohort | 294 | 40 - low | Outpatients and inpatients, USA | 64.5 (5.5) | 90 |

| Lainchbury 2003 | Cross sectional/cohort | 205 | 34 - low | Emergency department, New Zealand | 70 (14) | 49 |

| Logeart 2002** | Cross sectional/cohort | 163 | 71 - high | Inpatients, France | 67.4 (14.8) | 67 |

| Maisel 2001 | Cross sectional/cohort | 200 | 48 - low | Inpatients and outpatients, USA | 65.3 (0.9) | 95 |

| Mak 2004 | Cross sectional/cohort | 100 | 16 - low | Inpatients and outpatients, USA | 64 (13) | 97 |

| Monfort 2015 | Cross sectional/cohort | 163§ | 69 - high (class II-IV) | Cardiac rehabilitation, France | Median 58 | 81 |

| Prontera 2005 | Cross sectional/cohort but similar to case-control | 284 (214 confirmed+91 healthy) | 57 - high (of 213) | Unclear, Italy | Confirmed 62 (13); healthy 43.2 (13.4) | Confirmed 77; healthy 44 |

| Prosen 2011 | Cross sectional/cohort | 218 | 59 - high | Prehospital emergency, Slovenia | 63.3 (16.1) | 71 |

| Ro 2011 | Cross sectional/cohort | 250 | 43 - low | Emergency department, USA | 70.7 (13.8) | 57.8 |

| Shao 2005 | Cross sectional/cohort | 103 | 61 - high | Unclear, China | Not stated | Not stated |

| Storti 2004 | Cross sectional/cohort but similar to case-control | 296 (202 cardiac+94 healthy) | 59 - high (of 227) | Cardiac inpatients, Italy | Cardiac: 59.3 (20.5); healthy: 43.5 (14) | Cardiac: 70.3; healthy: 39.4 |

| Su 2015 | Cross sectional/cohort | 268 | 56 - high (of 203) | Emergency department, China | All 74.1 (7.9) | All 56.3 |

| Tang 2005 | Case-control | 348 (241 confirmed+107 healthy) | 69 - high | Secondary care, USA | Confirmed: male 69.4, female 69.1; Normal: male 44.0, female 44.9 | Not stated |

| Taylor 2017 | Cross sectional/cohort | 304 | 34 - low | Primary care, England | 73.9 (8.8) | 40.8 |

| Tomonaga 2011 | Cluster randomised controlled trial | 369 (218 in POCT group) | 44 - low (of 70 from POCT group) | Primary care, Switzerland | POCT group 65 (16) | POCT group 57.9 |

| Verdu 2012 | Cross sectional/cohort | 220 | 24 - low | Primary care, Spain | 73.2 (19.2) | 34.5 |

| Villacorta 2002 | Cross sectional/cohort | 70 | 51 - high | Emergency department, Brazil | 72.4 (15.9) | 47 |

| Watson 2016 | Cross sectional/cohort | 1368 (966 diabetes, 402 no diabetes) | 19 - low | Primary care, Ireland | Diabetes: 65.7 (58.6-71.6); no diabetes: 67.9 (59.5-74.4) | Diabetes: 64.9; no diabetes: 47.0 |

| Weekes 2016 | Cross sectional/cohort | 116 | 22 - low | Emergency department, USA | 59 (26) | 51 |

| Wei 2005 | Cross sectional/cohort | 135 | 45 - low | Outpatients, China | 67.8 (11.9) | 63 |

| Wieczorek 2002 | Case-control | 1050 (409 cardiac+641 controls) | 39 - low | Inpatients and outpatients, USA | Not stated | Not stated |

| Zapata 2014 | Cross sectional/cohort | 86 | 58 - high | Inpatients, Spain | 63.8 (12.7) | 66.3 |

| Zhao 2008 | Cross sectional/cohort | 195 | 69 - high | Inpatients, China | 72.1 (8.3) | 51.8 |

| Eligible studies not included in analysis | ||||||

| Morrison 2002 | Cross sectional/cohort | 321 | 42 - low | Emergency department, USA | Not stated | Not stated |

| Vanderheyden 2006 | Cross sectional/cohort | 72 | 56 - high | Inpatients, Belgium | 65 (12) | 71 |

POCT=point-of-care testing.

As defined by reference standard, which, if based on clinical assessment, could use a single test or multiple tests.

Mean (SD), or median (interquartile range) unless stated otherwise.

Reported baseline characteristics in groups based on blood pressure and hypertension history—numbers refer to patients with blood pressure status recorded.

All with confirmed heart failure.

Mean (range).

Arrivals at emergency department, but 90% were later admitted to intensive care.

Evaluated diagnostic accuracy using four different definitions of heart failure: New York Heart Association classes III and IV, left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, fluid retention, and American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stages C and D, respectively.

Table 2.

Included studies, point-of-care tests and thresholds, and reference tests

| Studies | Point-of-care tests* | Thresholds (pg/mL) | Reference tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies included in analysis | |||

| Ajuluchukwu 2009 | Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP) | 95, 100, 105, 110, 113, 115, 200, 122, 124, 125, 126, 127, 130, 135, 140, 145 | Clinical evaluation and echocardiography. Evaluation of cases and controls by study assistant, senior registrar, or investigator |

| Alibay 2005 | Triage (BNP) | 50, 100, 150, 200 | Retrospective review by two senior cardiologists |

| Blondé-Cynober 2011 | Triage (BNP) | 18, 100, 129, 400, 635 | Retrospective review by cardiologist and geriatrician |

| Breathing not properly study: | |||

| Maisel 2002 | Triage (BNP) | 50, 80, 100, 125, 150 | Retrospective review by two cardiologists |

| Maisel 2003 | Triage (BNP) | Additional 200, 300, 400 | Retrospective review |

| Pahle 2009 | Triage (BNP) | Additional 120, 140, 160, 180 | Retrospective review |

| Chenevier-Gobeaux 2010 | Triage (BNP) | 100 | Retrospective review by two senior emergency physicians |

| Dao 2001 | Triage (BNP) | 80, 100, 115, 120, 150 | Retrospective review by two cardiologists |

| De Vecchis 2016 | Alere (BNP) | 412 | New York Heart Association classification |

| Dokanish 2004 | Triage (BNP) | 250 | Retrospective review by cardiologist |

| Fischer 2001 | Triage (BNP) | 130 | Echocardiography |

| Fuat 2006 | Triage (BNP). | 40, 100 | Echocardiography |

| Gorissen 2007 | Triage (BNP) | 78, 225, 260, 309 | Retrospective review by cardiologist and pulmonologist |

| Gruson 2009 | Biosite SOB panel (BNP) | 100 | Retrospective review |

| Jungbauer 2012 | Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP); Triage (BNP) | 410; 117 | Based on clinical signs, physical examination, and echocardiography |

| Knudsen 2004 | Triage (BNP) | 50, 100, 150, 200 | Retrospective review by two cardiologists |

| San Diego veterans’ study: | |||

| Krishnaswamy 2001 | Triage (BNP) | 49, 62, 75, 110, 160, 345 | Retrospective review of echocardiography, admission treatment for heart failure, and visits to the emergency department for heart failure |

| Lubien 2002 | Triage (BNP) | Additional 17.5, 62, 92, 130 | Echocardiography |

| Lainchbury 2003 | Triage (BNP) | 69, 104, 208, 277, 346 | Retrospective review by two cardiologists, with third cardiologist as adjudicator |

| Logeart 2002 | Triage (BNP)† | 80, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 400 | Retrospective review by two cardiologists and pneumologist |

| Maisel 2001 | Triage (BNP) | 38.5, 46, 55, 65, 75 | Echocardiography |

| Mak 2004 | Triage (BNP) | 90, 173, 279, 402 | Echocardiography |

| Monfort 2015 | Alere (BNP) | 159 | New York Heart Association classification |

| Prontera 2005 | Triage (BNP) | 5.1, 29 | Retrospective review |

| Prosen 2011 | Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP) | 1000 | Retrospective review by cardiologists or intensive care physicians, or both |

| Ro 2011 | Triage (BNP); Abbott i-STAT (BNP) | 100; 100 | Based on discharge diagnosis, echocardiography (when available), and assessment of a consulting cardiologist |

| Shao 2005 | Triage (BNP) | 100 | Echocardiography, and cardiac catheterization |

| Storti 2004 | Triage (BNP) | 40.7 | Based on clinical (presence of suggestive symptoms), and echocardiographic evidence |

| Su 2015 | RAMP (NTproBNP) | 600 | Retrospective review |

| Tang 2005 | Triage (BNP) | 52, 74, 100 | Retrospective review |

| Taylor 2017 | Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP) | 125, 400 | Retrospective review by expert panel |

| Tomonaga 2011 | Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP) | 125 | Retrospective review |

| Verdu 2012 | Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP) | 125, 280, 400 | Retrospective review by one cardiologist |

| Villacorta 2002 | Triage (BNP) | 200 | Retrospective review by one cardiologist |

| Watson 2016 | Triage (BNP) | 10, 15, 25, 30, 50 | Echocardiography |

| Weekes 2016 | Abbott i-STAT (BNP) | 90 | Echocardiography |

| Wei 2005 | Triage (BNP) | 40 | Retrospective review by two cardiologists |

| Wieczorek 2002 | Triage (BNP) | 100 | Retrospective review by one physician |

| Zapata 2014 | Triage (BNP) | 125, 100 | Echocardiography |

| Zhao 2008 | Triage (BNP) | 50, 80, 100, 130, 150 | Cardiac catheterisation |

| Eligible studies not included in analysis | |||

| Morrison 2002 | Triage (BNP) | 94, 105, 135, 195, 240 | Retrospective review by two cardiologists |

| Vanderheyden 2006 | Triage (BNP) | 29.3, 50, 100, 139 | Cardiac catheterisation |

NTproBNP=N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide; BNP=B-type natriuretic peptide; SOB=shortness of breath.

Point-of-care devices: Cardiac Reader/Cobas h 232 (Roche Diagnostics); Triage (Biosite Diagnostics); RAMP (Response Biomedical Corporation), Abbott i-STAT (Abbott Point of Care); AlereTM Heart Check (Alere).

Two point-of-care tests (Triage, to measure BNP, and Hewlett Packard Sonos 1500, to provide Doppler echocardiography) were compared with the same reference test to indirectly compare BNP with Doppler echocardiography. Only point-of-care test is listed in table.

Various thresholds were used for the index tests, ranging from 5.1 to 412 pg/mL for BNP and 117 to 1000 pg/mL for NTproBNP (table 2). Thirty three studies reported data for BNP and seven for NTproBNP. Of the studies that gave diagnostic accuracy statistics at unique threshold values, the most common threshold for BNP was 100 pg/mL (15 of 33 studies)—the BNP threshold recommended by NICE and ESC (acute setting).5 6 The most common threshold for NTproBNP was 125 pg/mL (4 of 7 studies)—the threshold recommended by ESC (non-acute setting). No studies reported BNP data at 35 pg/mL—the BNP threshold recommended by ESC (non-acute setting), and none reported NTproBNP data at 300 pg/mL—the threshold recommended by ESC (acute setting). Two studies reported NTproBNP data at 400 pg/mL—the threshold recommended by NICE.

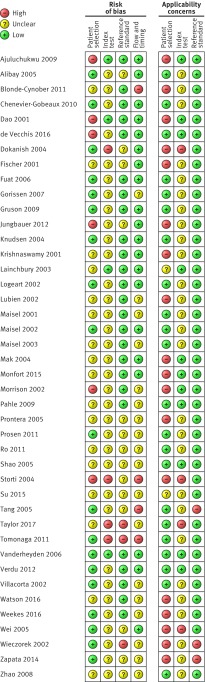

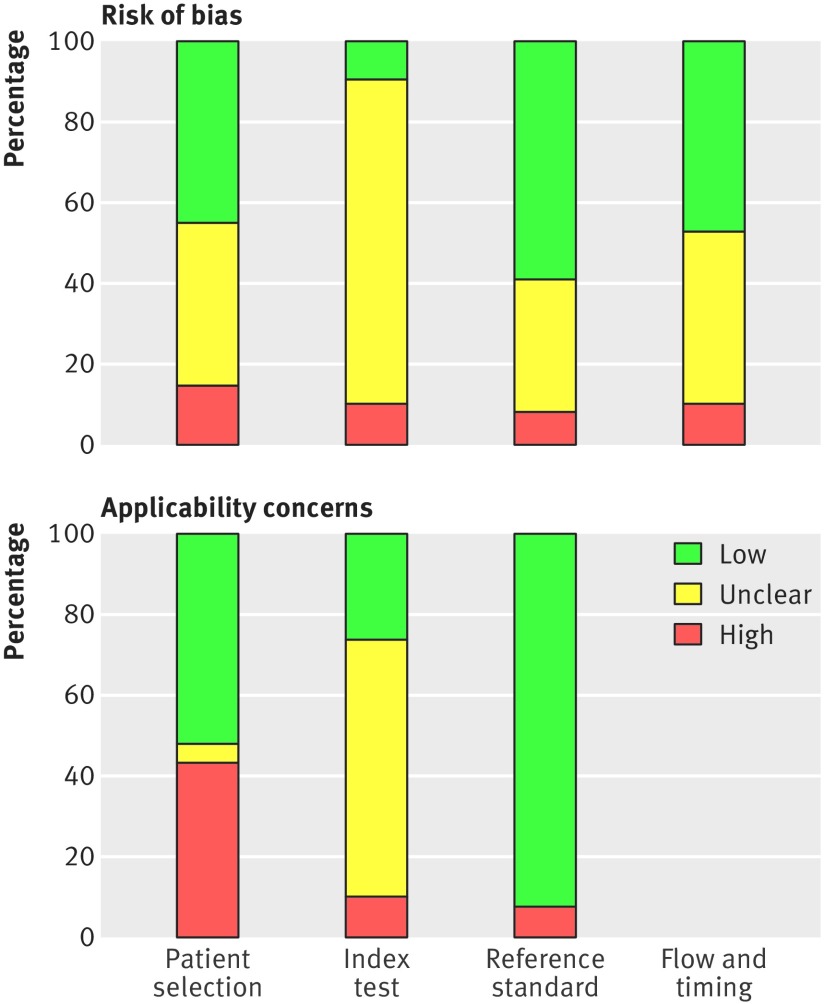

Methodological quality of included studies

All included studies were assessed using the QUADAS-2 framework. Figures 2 and 3 summarise the overall risk of bias and applicability concerns. For patient selection, the risk of bias overall was generally low as most studies included consecutive series of patients with suspected or confirmed CHF. However, applicability concerns were high with respect to the question of this systematic review, because the patients were often not representative of an ambulatory care population. The risk of bias for the index test was generally unclear because in most studies it was not obvious whether the thresholds used had been prespecified, with some using study derived thresholds, and whether the index test was performed blinded to the results of the reference test. Applicability concerns for the index test were also considered unclear because of blinding as it was not obvious how the point-of-care natriuretic tests would perform if interpreted without knowing the results of the reference tests, which would be the case if they were done in ambulatory and primary care settings as part of a diagnostic investigation. The risk of bias and applicability concerns for the reference standard were both assessed as low because most studies used an appropriate reference standard—clinical examination or echocardiography, or both. Flow and timing was rated as low risk of bias; however, several studies were rated as unclear risk of bias because the time interval between tests was often not explicitly reported.

Fig 2.

QUADAS-2 summary of risk of bias and applicability concerns showing review authors’ judgments about each domain for each included study. Based on 42 publications (39 studies)

Fig 3.

QUADAS-2 risk of bias and applicability concerns graph showing review authors’ judgments about each domain as percentages of included studies. Based on 42 publications (39 studies)

We found no evidence of publication bias (see supplementary fig S1). The number of studies included in the analysis was, however, small so the power to detect bias was low.

Our analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of the peptides was based on data from 40 publications of 37 individual studies that met our inclusion criteria and provided usable data (fig 1).

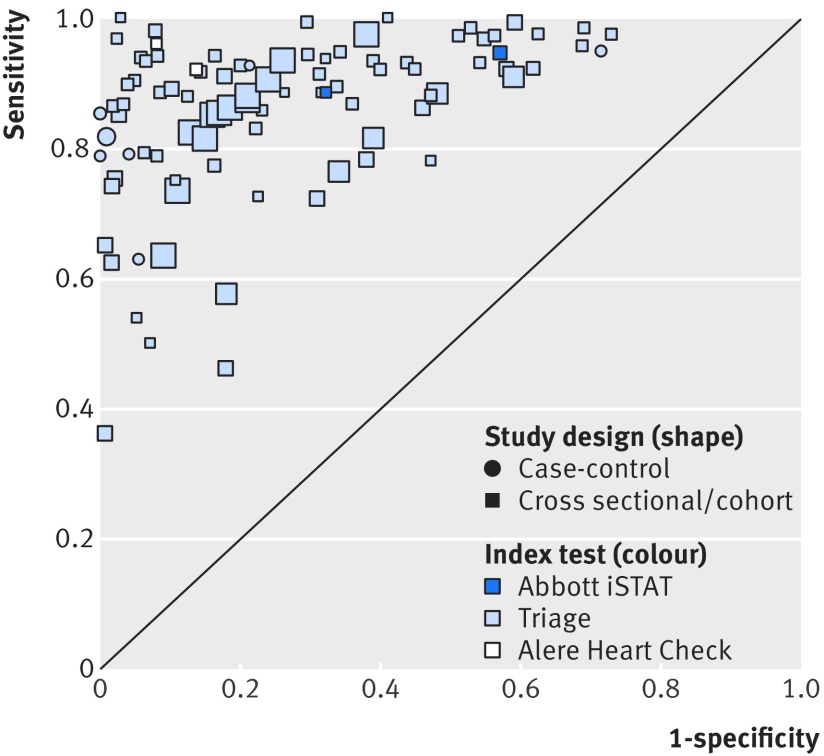

B-type natriuretic peptide

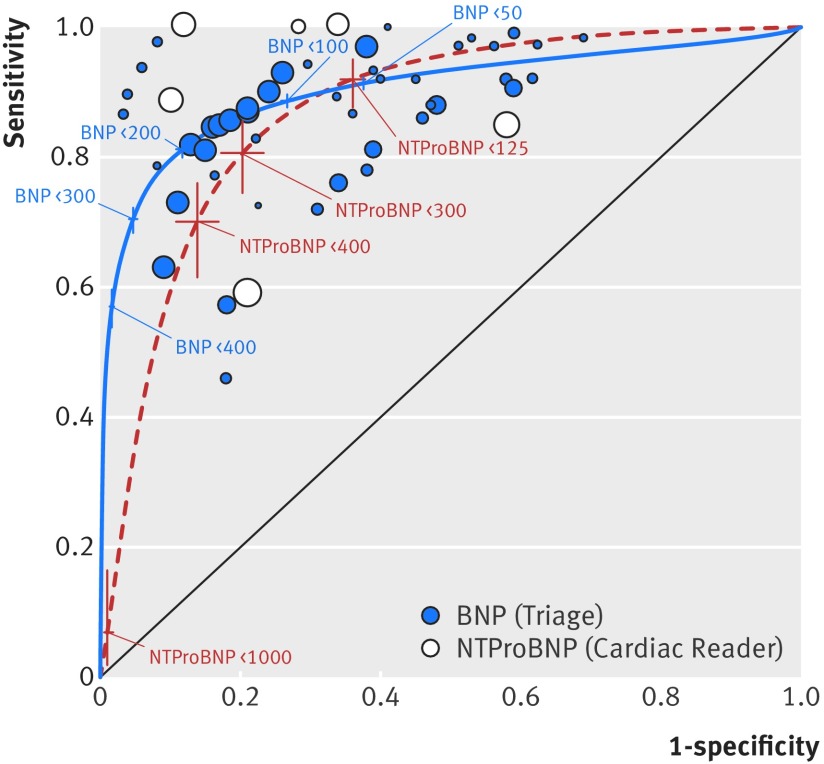

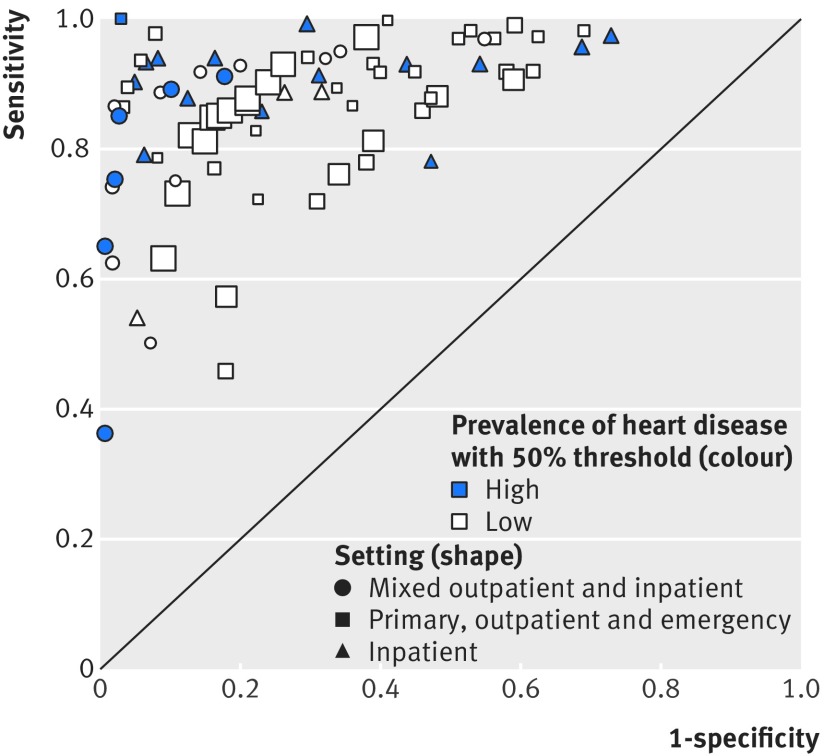

Figure 4 provides an overview of the results from 32 publications reporting data from 29 individual studies on the accuracy of point-of-care BNP tests compared with clinical assessment, grouped by study design and index test manufacturer for all thresholds. Most studies assessed the accuracy of the Triage test (light blue symbols) compared with clinical assessment using a cross sectional/cohort design (squares). Two studies reported the accuracy of the Abbott iSTAT test (dark blue symbols) and two reported the accuracy of the Alere Heart Check test in patients with confirmed CHF (white symbols). The reported sensitivity and specificity varied considerably between studies. The lowest sensitivity came from one study on a primary care population with very low prevalence of CHF (19%)27 and two studies on inpatient and outpatient populations that used BNP thresholds >345 pg/mL.30 31

Fig 4.

Receiver operating characteristic plot of B-type natriuretic peptide compared with clinical assessment, grouped by study design and index test for all thresholds. Based on data for 29 studies (32 publications). Size of symbol indicates study size

The accuracy of the point-of-care BNP test in populations with a high (dark blue symbols) compared with a low (white symbols) prevalence of CHF in ambulatory care settings (squares) varied considerably between studies and at different thresholds (fig 5).

Fig 5.

Receiver operating characteristic plot of B-type natriuretic peptide compared with clinical assessment, grouped by setting and prevalence of heart failure, for cross sectional/cohort studies and all thresholds. Based on data for 22 studies (25 publications). All index tests were Triage. Size of symbol indicates study size. Excludes one study (Shao 2005) because setting was not clear

For the cross sectional/cohort studies in ambulatory care settings that had populations with a low prevalence of CHF, the two primary care studies had a CHF prevalence of 19% and 38%, the outpatient study a prevalence of 45%, and the 12 emergency care studies a prevalence ranging from 20% to 50%.

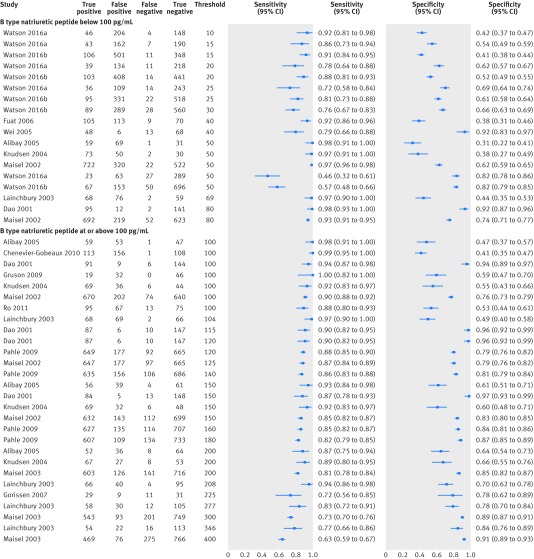

The sensitivity of BNP testing in these studies was slightly less variable than the specificity, and sensitivity decreased as the threshold increased (fig 6). Of note, at thresholds <100 pg/mL, several studies reported low sensitivities and specificities (<0.8) of the test, and variations in sensitivity and specificity did not appear to correlate with increasing threshold. At a threshold of <100 pg/mL, sensitivity ranged from 0.46 (95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.61) to 0.98 (0.93 to 1.00) and specificity from 0.31 (0.22 to 0.41) to 0.98 (0.95 to 1.00). The two studies23 27 in a primary care setting reported sensitivities ranging from 0.46 (0.32 to 0.61) to 0.92 (0.81 to 0.98) and specificities from 0.38 (0.31 to 0.46) to 0.82 (0.79 to 0.85) at a range of thresholds <100 pg/mL (10-50 ng/mL). The study by Watson et al,27 which reported the lowest sensitivity, included a population with a low prevalence of CHF (19%) as it included patients with risk factors for cardiovascular disease, not with symptoms of CHF.

Fig 6.

Paired sensitivity and specificity plots at two threshold levels for B-type natriuretic peptide compared with clinical assessment, for cross sectional/cohort studies with populations of low prevalence of chronic heart failure in ambulatory care settings. Based on data for 13 studies (15 publications). All index tests were Triage. Watson 2016a refers to a population with diabetes and Watson 2016b to a population without diabetes

When we pooled data at and around the thresholds recommended by the ESC and NICE guidelines for studies in ambulatory care settings and with a low prevalence of CHF (see supplementary table S2), the sensitivity of BNP was highest at 100 pg/mL (recommended by NICE for all settings and by ESC for acute settings5 6): pooled sensitivity 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.90 to 0.98) and pooled specificity 0.64 (0.46 to 0.78). This was based on seven studies in emergency settings with a prevalence of CHF between 20% and 48%.

Only one cross sectional/cohort study32 had a high prevalence of CHF in an ambulatory care setting and reported a sensitivity of 1.00 (0.90 to 1.00) and specificity of 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) at 100 pg/mL threshold for the Triage test.

In the few cross sectional/cohort studies with a low prevalence of CHF in mixed inpatient and outpatient settings (see supplementary fig S2), variations in sensitivity and specificity correlated with increasing threshold.

N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide

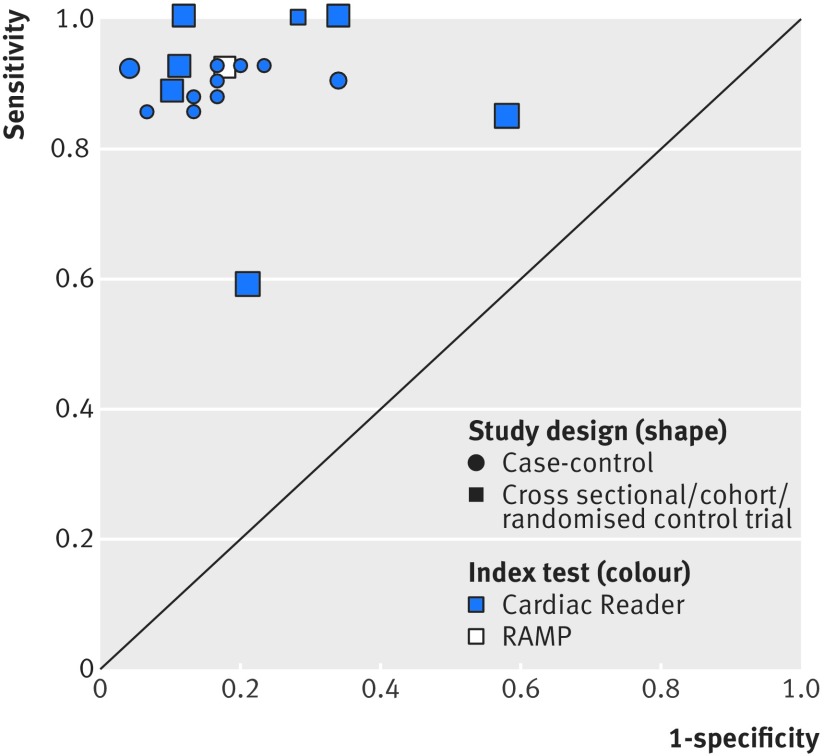

Most NTproBNP studies reported results for the Cardiac Reader NTproBNP test compared with clinical assessment. Figure 7 shows the results from seven individual studies reporting the accuracy of point-of-care NTproBNP testing compared with clinical assessment, grouped by study design and index test manufacturer for all reported thresholds. Two index tests were evaluated: the Cardiac Reader (Roche; six studies, blue symbols) and RAMP (Response Biomedical; one study, white symbol). Three of these studies were done in a primary care setting.24 25 26 Overall, sensitivity and specificity were less variable than those reported for BNP, with the exception of one of the primary care studies,24 where the reported sensitivity and specificity were lower than those reported in other studies. For this study, a risk of bias was identified for the reference test and patients were preselected using a clinical decision rule.

Fig 7.

Receiver operating characteristic plot of N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide compared with clinical assessment, grouped by study design and index test for all thresholds. Based on data for seven studies. Size of symbol indicates study size

In studies in ambulatory care settings with a cross sectional/cohort design at 125 pg/mL, the threshold recommended by ESC for non-acute settings, the paired sensitivity and specificity plots for the Cardiac Reader test show high sensitivity (see supplementary table S2, pooled sensitivity based on three primary care studies,24 25 26 0.99 (95% confidence interval 0.57 to 1.00)) and moderate specificity (pooled specificity 0.60 (0.44 to 0.74)), and increased specificity at higher thresholds (fig 8, supplementary table S2). At 400 pg/mL (the threshold recommended by NICE), in the two studies done in a primary care setting, sensitivity ranged from 0.59 (0.49 to 0.68) to 0.88 (0.77 to 0.96) and specificity from 0.79 (0.73 to 0.84) to 0.90 (0.84 to 0.94). Sensitivity and specificity were consistently high in the case-control studies (see supplementary fig S3).

Fig 8.

Paired sensitivity and specificity plots at two thresholds levels for N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide compared with clinical assessment, for cross sectional/cohort/randomised controlled trial studies. Based on data for four studies. All index tests were Cardiac Reader

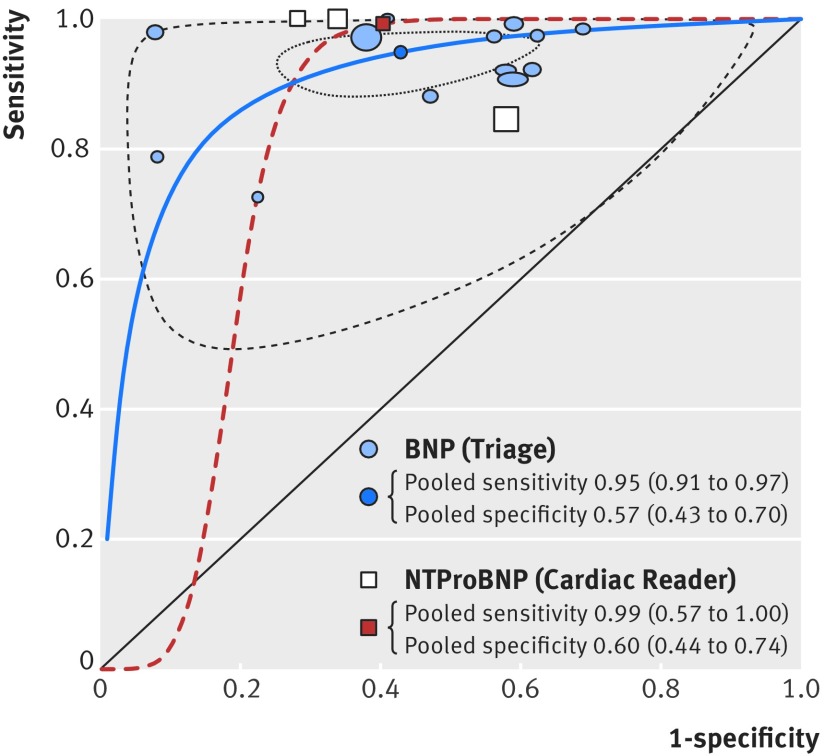

Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of the two peptides

The summary receiver operating characteristic plots assessing BNP and NTproBNP tests, each compared with clinical assessment and at the lowest threshold for each study, showed that NTproBNP was slightly more accurate than BNP (fig 9), but the difference was not statistically significant (Triage (BNP) pooled sensitivity 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.92 to 0.97), pooled specificity 0.57 (0.43 to 0.70); Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP) pooled sensitivity 0.97 (0.57 to 1.00), pooled specificity 0.69 (0.44 to 0.74)). The confidence and prediction regions were wide for NTproBNP because of the lack of data (not shown).

Fig 9.

Summary receiver operating characteristic plots for B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP) compared with clinical assessment, for cross sectional/cohort/randomised controlled trial studies of populations with low prevalence of heart failure in primary, outpatient, and emergency settings and the lowest threshold for each study. Based on data for 15 studies, 3 NTproBNP and 12 BNPs. Size of symbol indicates study size. Studies were insufficient to draw meaningful prediction and confidence regions for NTproBNP

Removing the outlier24 did not alter this result (Cardiac Reader (NTproBNP) pooled sensitivity 0.99 (0.75 to 1.00), pooled specificity 0.77 (0.62 to 0.87)). When emergency care studies with a high prevalence of CHF were also included, there was also no significant difference (see supplementary fig S4). Sensitivities remained high, with sensitivity slightly higher for NTproBNP, and confidence intervals overlapped.

At all thresholds, the diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NTproBNP was comparable (fig 10). The summary receiver operating characteristic plots were similar and the confidence intervals generally overlapped. BNP points clustered around the point estimate of sensitivity 0.85 and specificity 0.80, whereas NTproBNP points were more scattered because of lack of data.

Fig 10.

Summary receiver operating characteristic plots for B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP) compared with clinical assessment, for cross sectional/cohort studies/randomised controlled trial studies of populations with low prevalence of heart failure in primary, outpatient, and emergency settings and at all thresholds. Based on data for 18 publications (15 studies), 3 NTproBNP and 12 BNP. Size of symbol indicates study size

Because of concerns about patient selection, we tested for heterogeneity between studies using BNP data in the cross sectional/cohort studies with a low prevalence of CHF and in ambulatory care settings. NTproBNP data were insufficient for testing. Four of the 15 studies either had a high risk of bias or had applicability concerns about patient selection, or both were uncertain. We did not find evidence of heterogeneity between studies (likelihood ratio test result, P=0.4) for patient selection. The power to detect heterogeneity was low because of the small number of studies included in the analysis.

After excluding the four studies for which we had concerns about patient selection, we again compared the diagnostic accuracy of the two peptides at the lowest threshold for each study. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were not significantly different, with sensitivity only slightly higher and NTproBNP still slightly more accurate (Triage BNP: pooled sensitivity 0.96 (95% confidence interval 0.90 to 0.98), pooled specificity 0.50 (0.39 to 0.60)).

Discussion

In populations with a low prevalence of chronic heart failure (CHF) in ambulatory care settings, the diagnostic accuracy of peptide testing varied and data in primary care settings were limited. In emergency care populations with a low prevalence of CHF, the diagnostic accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) measured with the point-of-care device Triage at thresholds at and above 100 pg/mL was similar to that in an acute setting, with sensitivity generally high. Sensitivity was highest at 100 pg/mL, the threshold recommended in the NICE and ESC guidelines (acute setting) (0.95, 95% confidence interval 0.90 to 0.98), and specificity varied. However, in the two primary care studies that reported BNP at and below thresholds of 50 pg/mL, sensitivity and specificity varied widely.

Only five of the 15 studies in ambulatory care settings were done in primary care, and the prevalence of CHF varied (19% to 44%).

Fewer studies assessed the accuracy of N terminal fragment pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP). Based on three studies in primary care that used the Cardiac Reader, the sensitivity of NTproBNP was high at 125 pg/mL, the ESC recommended threshold for non-acute settings (0.99, 95% confidence interval 0.57 to 1.00).

No statistically significant difference was found in diagnostic accuracy between point-of-care BNP and NTproBNP testing.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study provides a comprehensive review of the current evidence on the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care BNP and NTproBNP tests in the diagnosis of CHF in ambulatory care at all thresholds. However, a limitation of our analysis was the few data in primary care settings and the few data for NTproBNP. The lack of data also limited the power of our statistical tests. The risk of bias assessment highlighted that in several studies it was unclear whether assessors interpreting the results of the point-of-care index test (BNP or NTproBNP) were blinded to the outcome of the reference test (eg, clinical assessment, echocardiography). The lack of blinding may lead to an overestimation of the test accuracy.33 Therefore, if these tests are used in general practice without a reference test, their performance is still not known. Furthermore, the heterogeneity in assessment of the reference standard across studies might affect generalisability of these findings to settings with different diagnostic protocols for patients with CHF, which would result in a different specificity of the test used. To ensure generalisability to primary care patients, we focused on studies in ambulatory care settings—primary, outpatient, and emergency—where ambulatory patients with heart failure would present and populations would have a low prevalence of heart failure. Although some patients arriving at the emergency department will not be ambulatory, many of the included studies supported the inclusion of low risk emergency settings as an ambulatory setting by excluding high risk cases (acute coronary syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, unstable angina, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, and trauma). Our sensitivity analysis showed that adding emergency care studies with populations with a higher prevalence of CHF did not alter our conclusion that testing for NTproBNP was slightly more accurate than testing for BNP to exclude CHF, which added support for including emergency settings in our analysis. Given our data limitations and the heterogeneity between studies, we cannot draw firm conclusions about appropriate thresholds; instead we summarise the data where possible and present some tentative conclusions.

Comparison with previous findings

Previous research on the diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NTproBNP include reviews published in 2007, 2008, and 2015. The 2007 review by Clerico et al analysed studies with paired measurement of NTproBNP and BNP in the emergency department and found no difference.9 Similar results were reported in the 2008 meta-analysis by Worcester et al.14 The diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NTproBNP testing was also found to be similar in the recent 2015 review by Roberts at al.12 All three reviews focused on studies carried out in the hospital setting, and they included laboratory tests. Our review of point-of-care tests included 11 studies from the 2015 review; of these, nine were in an ambulatory care setting. We included and analysed data from 12 more ambulatory care studies. We used a meta-analysis method that allowed the use of all available data at different thresholds, thereby providing a comprehensive analysis.19 The 2015 review, which assessed the diagnostic accuracy of natriuretic peptides for heart failure in the acute setting, concluded that the use of BNP and NTproBNP testing at the thresholds of the 2012 ESC guideline had excellent ability to exclude a diagnosis of acute heart failure because reported sensitivities were sufficiently high (approaching 1).12 The sensitivities of point-of-care tests in the ambulatory care setting assessed in our review were more variable than in the acute setting, particularly in the primary care setting.

Implications for clinical practice

As the sensitivity in the primary care setting is variable, it is unclear whether point-of-care tests could be used to exclude CHF in primary care. This variability could be because patients with CHF in primary care often present with non-specific symptoms, such as breathlessness. Furthermore, the generally low specificity of these tests in primary care may limit their use as a test to help confirm CHF in primary care, although the NTproBNP test may perform slightly better than the BNP test as a test to rule out CHF because of its higher sensitivity and less variability reported in most studies.

As with any test, the results need to be interpreted in the context of general clinical assessment. If the clinical presentation clearly indicates CHF or a different diagnosis, clinical judgment should overrule a single point-of-care test result.

The limited data from studies in a primary care setting suggest that the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care BNP and NTproBNP testing at lower thresholds is insufficient. It should also be noted that the thresholds used in many of the studies are likely to be too high to be applicable to primary care. However, some studies reported a high sensitivity, particularly for NTproBNP to exclude CHF at the ESC threshold of 135 pg/mL in non-acute care, which suggests that this threshold might be appropriate for point-of-care testing. This finding is only tentative, given the limitations of our data. As with peptide testing in hospitals, point-of-care testing in ambulatory care would need to follow established clinical guidelines by confirming positive NTproBNP test results with cardiac imaging and ensuring an appropriate safety net through follow-up appointments.5 6

Implications for future research

Given the lack of studies in a primary care setting and potential methodological limitations in the studies that have been done, large scale trials in primary care are needed to assess the role of point-of-care natriuretic peptide testing in improving the care of patients with heart failure and its effect on patient outcomes, such as morbidity and mortality.

Conclusions

In ambulatory care settings in populations with a low prevalence of CHF, the sensitivity of BNP point-of-care tests at 100 pg/mL, the threshold recommended by NICE and ESC for acute care, is high but this threshold may not be appropriate for the primary care setting specifically. At lower thresholds, including the ESC recommended threshold for non-acute care of 35 pg/mL, results in primary care settings vary. Testing for NTproBNP might be slightly better than testing for BNP to exclude CHF, and the ESC threshold for non-acute care may be appropriate for NTproBNP point-of-care testing; however, prospective trials would need to confirm this. Point-of-care testing, supported by confirmatory testing such as ultrasound imaging, might improve the management of patients with CHF in ambulatory care.

What is already known on this topic

Owing to improved survival rates, the prevalence of heart failure will continue to increase; if detected early, heart failure may be reversible with appropriate treatment

Point-of-care testing for natriuretic peptides in primary care and other ambulatory care settings could enable the identification and rapid referral of patients with heart failure, and align with the increasing drive to move care from hospital settings to the community

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence and European Society for Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend testing for natriuretic peptides to aid the diagnosis of heart failure, and have recommended thresholds to exclude heart failure, but the diagnostic accuracy at these thresholds in ambulatory care is unknown

What this study adds

B-type natriuretic peptide has variable ability to exclude chronic heart failure in patients in ambulatory care at low thresholds, but the ESC threshold for non-acute care for N terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide might be an appropriate cut-off for point-of-care testing in this setting

As with peptide testing in acute care, given the variability of the specificity of natriuretic peptides, clinical guidelines must be followed and all positive test results confirmed by cardiac imaging and appropriately followed up

Acknowledgments

We thank Nia Roberts for assistance in conducting the search strategy, the Stakeholder Group and Steering Committee of our NIHR programme grant for discussions that inspired this paper, and Elizabeth Holloway and Marion Judd (members of the Patient & Public Involvement Group) for suggestions that have improved the text.

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Supplementary information: Additional tables, figure, and references

Contributors: AP, CB, and RP conceived and designed the study. AP and CB did the initial search, and KST, AP, and CB did the updated search. KST, AP, and CB selected studies for inclusion. KST, AP, CB, and JYV extracted data. KST did the data analysis with advice from RP and JYV. JYV and CPP gave clinical advice in interpreting the results. BGF produced the R plots and prepared the figures for journal submission. KST, AP, CB, and JYV wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all authors contributed critically to subsequent revisions and approved the final manuscript. KST had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. KST and AP are guarantors. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under the programme grants for applied research programme (RP-PG-1210-12003). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. KST receives funding from the NIHR programme for applied research. JYV and CPP receive funding from the NIHR Diagnostic Evidence Co-operative (DEC). BGF receives funding from the NIHR Monitoring Grant and Research Capability Fund. RF receives funding from the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre programme, the NIHR programme for applied research, the NIHR HPRU Gastrointestinal Infections Group, and the NIHR DEC. CB receives funding from the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre programme, the NIHR programme for applied research, and Cancer Research UK. AP receives funding from the NIHR and the NIHR School of Primary Care Research. The funders had no role in the study design; data collection; data analysis and interpretation; writing of the report; or the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: KST reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study; JYV reports grants from NIHR DEC, during the conduct of the study; BGF reports grants from NIHR, during the conduct of the study; CPP reports funding from an NIHR grant and occasionally receipt of honorariums and expenses for speaking at meetings, and writing white papers on the generic topic of point-of-care testing; RP reports grants from NIHR UK programme of applied research during the conduct of the study; CB reports grants from NIHR programme grant for applied research, grants from NIHR School of Primary Care Research, grants from Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford during the conduct of the study; AP reports grants from NIHR and from NIHR School of Primary Care Research during the conduct of the study, and occasionally receives expenses for teaching evidence based medicine.

Ethical approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead author and manuscript’s guarantor (KST) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

References

- 1.Townsend N, Wickramasinghe K, Bhatnagar P, et al. Coronary heart disease statistics 2012 edition. British Heart Foundation, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zaphiriou A, Robb S, Murray-Thomas T, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of plasma BNP and NTproBNP in patients referred from primary care with suspected heart failure: results of the UK natriuretic peptide study. Eur J Heart Fail 2005;7:537-41. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mant J, Doust J, Roalfe A, et al. Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of diagnosis of heart failure, with modelling of implications of different diagnostic strategies in primary care. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:1-207, iii. 10.3310/hta13320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zuber M, Cuculi F, Attenhofer Jost CH, et al. Value of brain natriuretic peptides in primary care patients with the clinical diagnosis of chronic heart failure. Scand Cardiovasc J 2009;43:324-9. 10.1080/14017430902769919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Clinical Guideline Centre. Chronic heart failure: national clinical guideline for diagnosis and management in primary and secondary care. National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010. [PubMed]

- 6. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. Authors/Task Force Members. Document Reviewers 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:891-975. 10.1002/ejhf.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balion C, Santaguida PL, Hill S, et al. Testing for BNP and NT-proBNP in the diagnosis and prognosis of heart failure. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2006;(142):1-147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Turner PJ, Van den Bruel A, Jones CH, et al. Point-of-care testing in UK primary care: a survey to establish clinical needs. Fam Pract 2016;33:388-94. 10.1093/fampra/cmw018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clerico A, Fontana M, Zyw L, Passino C, Emdin M. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and the N-terminal part of the propeptide of BNP immunoassays in chronic and acute heart failure: a systematic review. Clin Chem 2007;53:813-22. 10.1373/clinchem.2006.075713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korenstein D, Wisnivesky JP, Wyer P, Adler R, Ponieman D, McGinn T. The utility of B-type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of heart failure in the emergency department: a systematic review. BMC Emerg Med 2007;7:6. 10.1186/1471-227X-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Latour-Pérez J, Coves-Orts FJ, Abad-Terrado C, Abraira V, Zamora J. Accuracy of B-type natriuretic peptide levels in the diagnosis of left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure: a systematic review. Eur J Heart Fail 2006;8:390-9. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roberts E, Ludman AJ, Dworzynski K, et al. NICE Guideline Development Group for Acute Heart Failure The diagnostic accuracy of the natriuretic peptides in heart failure: systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis in the acute care setting. BMJ 2015;350:h910. 10.1136/bmj.h910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang CS, FitzGerald JM, Schulzer M, Mak E, Ayas NT. Does this dyspneic patient in the emergency department have congestive heart failure? JAMA 2005;294:1944-56. 10.1001/jama.294.15.1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Worster A, Balion CM, Hill SA, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of BNP and NT-proBNP in patients presenting to acute care settings with dyspnea: a systematic review. Clin Biochem 2008;41:250-9. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, et al. QUADAS-2 Group QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:529-36. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:982-90. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takwoingi Y, Riley RD, Deeks JJ. Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies in mental health. Evid Based Ment Health 2015;18:103-9. 10.1136/eb-2015-102228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bossuyt PM, Davenport C, Deeks J, Hyde C, Leeflang MM, Scholten RJ. Chapter 11. Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. In: Deeks J, Bossuyt PM, Gatsonis C, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy, version 0.9. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2013. http://methods.cochrane.org/sites/methods.cochrane.org.sdt/files/public/uploads/DTA%20Handbook%20Chapter%2011%20201312.pdf

- 19. Dukic V, Gatsonis C. Meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy assessment studies with varying number of thresholds. Biometrics 2003;59:936-46. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2003.00108.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:882-93. . 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leeflang MM, Deeks JJ, Gatsonis C, Bossuyt PM, Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working G, Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group Systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:889-97. 10.7326/0003-4819-149-12-200812160-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Song F, Khan KS, Dinnes J, Sutton AJ. Asymmetric funnel plots and publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:88-95. 10.1093/ije/31.1.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fuat A, Murphy JJ, Hungin AP, et al. The diagnostic accuracy and utility of a B-type natriuretic peptide test in a community population of patients with suspected heart failure. Br J Gen Pract 2006;56:327-33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taylor CJ, Roalfe AK, Iles R, et al. REFER investigators Primary care REFerral for EchocaRdiogram (REFER) in heart failure: a diagnostic accuracy study. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e94-102. 10.3399/bjgp16X688393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tomonaga Y, Gutzwiller F, Lüscher TF, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care testing for acute coronary syndromes, heart failure and thromboembolic events in primary care: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:12. 10.1186/1471-2296-12-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verdú JM, Comín-Colet J, Domingo M, et al. Rapid point-of-care NT-proBNP optimal cut-off point for heart failure diagnosis in primary care. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2012;65:613-9. 10.1016/j.rec.2012.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Watson C, James S, O’Connell E, et al. Influence of diabetes on natriuretic peptide thresholds in screening for Stage B heart failure. Biomarkers 2016;21:538-43. 10.3109/1354750X.2016.1160427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Vecchis R, Ariano C. Measuring B-type natriuretic peptide from capillary blood or venous sample: Is it the same? Cardiol Res 2016;7:51-8. 10.14740/cr468e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monfort A, Da Silva K, Vodovar N, Gayat E, Cohen-Solal A, Manivet P. Clinical evaluation of the Heart Check system, a new quantitative measurement of fresh capillary BNP. Biomark Med 2015;9:1323-30. 10.2217/bmm.15.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Krishnaswamy P, Lubien E, Clopton P, et al. Utility of B-natriuretic peptide levels in identifying patients with left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction. Am J Med 2001;111:274-9. 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00841-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mak GS, DeMaria A, Clopton P, Maisel AS. Utility of B-natriuretic peptide in the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function: comparison with tissue Doppler imaging recordings. Am Heart J 2004;148:895-902. 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Villacorta H, Duarte A, Duarte NM, et al. The role of B-type natriuretic peptide in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in patients presenting to an emergency department with dyspnea. Arq Bras Cardiol 2002;79:569-72, 564-8. 10.1590/S0066-782X2002001500002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Di Nisio M, Smidt N, van Rijn JC, Bossuyt PM. Evidence of bias and variation in diagnostic accuracy studies. CMAJ 2006;174:469-76. 10.1503/cmaj.050090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary information: Additional tables, figure, and references