Abstract

Background

Individual genome sequencing results are valued by patients in ways distinct from clinical utility. Such outcomes have been described as components of “personal utility,” a concept that broadly encompasses patient-endorsed benefits, that is operationally defined as non-clinical outcomes. No empirical delineation of these outcomes has been reported.

Aim

To address this gap, we administered a Delphi survey to adult participants in a National Institute of Health (NIH) clinical exome study to extract the most highly endorsed outcomes constituting personal utility.

Materials and Methods

Forty research participants responded to a Delphi survey to rate 35 items identified by a systematic literature review of personal utility.

Results

Two rounds of ranking resulted in 24 items that represented 14 distinct elements of personal utility. Elements most highly endorsed by participants were: increased self-knowledge, knowledge of “the condition,” altruism, and anticipated coping.

Discussion

Our findings represent the first systematic effort to delineate elements of personal utility that may be used to anticipate participant expectation and inform genetic counseling prior to sequencing. The 24 items reported need to be studied further in additional clinical genome sequencing studies to assess generalizability in other populations. Further research will help to understand motivations and to predict the meaning and use of results.

Keywords: Delphi, genetic testing, genomics, personal outcomes, personal utility, utility

1 | INTRODUCTION

With the expanding use of exome and genome sequencing,1 the amount of genetic variant information available has substantially increased. A significant portion of this information cannot yet be interpreted for patient management.2 Yet it is recognized that certain aspects of genetic information may have personal utility to patients beyond patient management.3 Examples of valued outcomes include preparing mentally for the future and facilitating reproductive planning. These extended utilities have been collectively referred to as “personal utility.”4,5

In medicine, measuring clinical utility is an important component of test evaluation. Clinical utility generally refers to the ability of a test to influence patient management.6 In genetic and genomic testing, the term “clinical utility” has been construed both narrowly and broadly, at times including elements of personal utility.7,8 Ravitsky and Wilfond3 include social and personal outcomes, such as reproductive planning and life planning decisions, as part of “clinical utility” and restrict personal “meaning” to more idiosyncratic aspects such as identity or relationships.

In contrast, other researchers refer to clinical utility by its narrowest definition: a test that will “lead to an improved health outcome.” For example, the ACCE (Analytic validity, Clinical validity, Clinical utility, and associated Ethical, legal and social implications) framework uses this definition of clinical utility and distinguishes personal utility as a separate entity termed ELSI (Ethical Legal and Social Implications).6 The ACCE framework, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the USA from 2000 to 2004, was created to guide genetic test evaluation.9 As many genetic tests may be limited in the extent to which they can contribute to medical management, inclusion of personal utility as a parameter for evaluation may be appropriate as it may expand the value of testing information.

Taken literally, the concept of personal utility describes benefits beyond clinical utility. While negative outcomes, or harms, resulting from genetic testing cannot be considered “of use” to individuals, patients have also raised concerns about potential harms in the context of personal utility. For example, these harms include potential violation of privacy, discrimination and stigma. Concern about potential harms informs decision-making such as whether to undergo testing. These concerns may lead to patients forgoing testing and its associated benefits.10 Given the importance of harms to test decision-making we investigated them in conjunction with personal utility in this study.

An article from the EGAPP (Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention) working group calls for additional research and method development to assess personal utility.11 While previous research and commentaries provide an extensive range of elements of personal utility, an empirical investigation of the concept is lacking. This study aimed to engage individuals who have undergone exome sequencing to empirically refine the scope of personal utility in this context and provide evidence to support use of personal utility as a valuable outcome in genomic test evaluation. We used a Delphi method to refine elements of personal utility, exploiting an opportunity to explore perceived outcomes from individuals undergoing exome sequencing.

2 | METHODS

2.1 | Delphi method

This study used the Delphi method which is an iterative process that uses a series of surveys and feedback to reach a consensus among content experts.12 We generated a survey based on published literature and distributed it among participants. The survey was piloted for clarity with genetic counseling students who had expertise in genomics concepts as well as members of the public who were a convenience sample of individuals known to the research team.

After participants ranked the relevance of the topics, and had the chance to add topics and to provide comments, we reviewed the responses and adjusted the survey to reflect the feedback. A revised survey was returned to the same participants for reassessment of the content. The Delphi process can continue for several rounds until a consensus is reached. However, most change in responses occurs after the first and second rounds.12,13 Two rounds were judged to be sufficient given the evidence that the first 2 rounds capture the majority of the change. We stopped after 2 rounds given the small number of changes in the responses to the plausibility of the items, and the drop off rate of the respondents. The question order was randomized in each of the 2 surveys.

2.2 | Sample

Participants were recruited from The ClinSeq Project study, which is an exome sequencing study that aims to enroll approximately 1500 participants.14 Participants eligible for the study were between 45 and 65 years of age at their original enrollment, English-speaking, and most were local to the Washington, DC, and Baltimore, Maryland areas. During an initial visit to The ClinSeq Project, participants underwent a clinical evaluation and were consented for exome sequencing. The original aim of The ClinSeq Project was to identify genetic variants contributing to heart disease, although over time the study aims have expanded to study all genetic variation and the majority of participants are ostensibly healthy volunteers. Sequence variants deemed clinically relevant are returned to participants following validation in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments. (CLIA)-approved laboratory. At the time of the Delphi study, some participants had received genetic test results and some had not. Including both groups was done in an attempt to capture personal utility as it is both expected and experienced. None of the participants received testing results between rounds.

For the Delphi study 162 participants were invited. These participants were selected to represent diversity in demographic characteristics including gender, race, ethnicity, education, income, and receipt of genetic test result. Diversity was limited given the characteristics of the cohort as a whole.15

2.3 | Recruitment

Potential participants were invited via telephone, secure email, and/or mail. Interested participants were given a link to access the survey online as well as a unique survey ID. Participants who completed survey 1 were recontacted when survey 2 was available, 2 weeks after the close of survey 1. All surveys were completed online expect for one that was completed on paper and returned by mail.

2.4 | Rounds

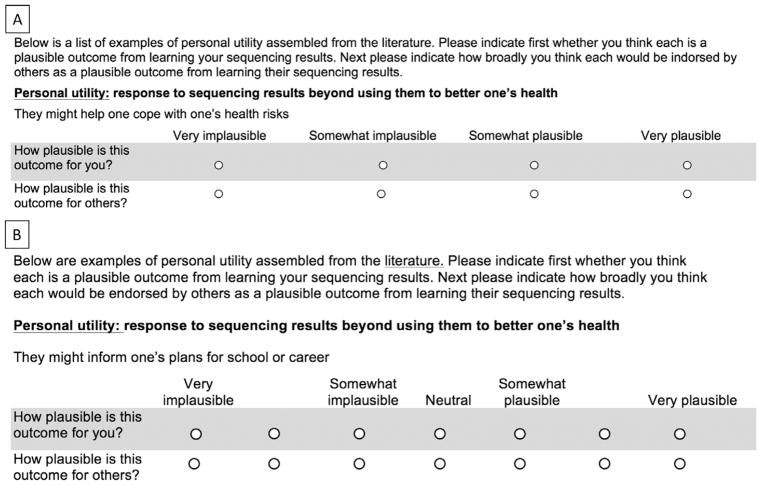

Survey items for round 1 were developed based on the findings from a systematic literature review of personal utility.16 The systematic review was conducted specifically in preparation for this study. The review identified elements of personal utility that were reported in the empirical literature, focusing on the concept as defined by participants or patients. “Items” are the individual questions posed to participants. Items exploring similar concepts were grouped into over-arching “elements.” Survey 1 contained 35 items describing 18 elements of personal utility, some of which were subdivided to completely represent the multidimensionality of the elements. For each item, participants were asked to rate its plausibility as an outcome of sequencing (see example, Figure 1A) on a scale from 1 to 4 (1 = “very implausible,” 4 = “very plausible”). Survey 1 also included open-ended questions asking participants to suggest additional elements to include.

FIGURE 1.

Sample survey item from survey 1 (A) and survey 2 (B).

There is evidence that when individuals are asked to envisage opinions or perceptions of “others” they find it difficult to separate “self” from “others.”17 To help orient participants to think about others, they were first asked to rate the plausibility “for you” and subsequently asked to rate the plausibility “for others.” Because the objective of this study was to understand items most plausible to all individuals seeking genome sequencing, only responses from the second part of each item (“how plausible is this outcome for others?”) were analyzed.

Survey 2 incorporated feedback from survey 1. Items that did not reach a specific threshold of agreement (see data analysis section) were removed, and items suggested in the open-ended questions were added. The scale for survey 2 ranged from 1 to 7 (1 = “very implausible,” 7 = “very plausible”) instead of 1 to 4 (see example, Figure 1B) in order to increase sensitivity of the scale. One open-ended question at the end of survey 2 invited participants to share any comments they had on the topic.

2.5 | Analysis

Ranked responses for surveys 1 and 2 were analyzed to elicit the median score and agreement fraction. Taken together, median and fraction of agreement more accurately represent the central measure of ordinal data.18 Items with a median <3 (<“somewhat plausible”) and an agreement fraction of <50% were removed from the item pool after survey 1. Items with a median <5 (<“somewhat plausible”) and an agreement fraction <50% were removed from the item pool after survey 2. Suggested items in the open-ended responses from survey 1 were reviewed for addition to survey 2.

3 | RESULTS

3.1 | Sample characteristics

Participants were evenly split by gender. Most (60%) were white; 38% were African-American and 1 participant was Hispanic/Latino. The majority of participants were between the ages of 50 and 70, and well educated. Most respondents had not yet received a genomic test result from the exome sequencing study. (Table 1)

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics

| Demographic characteristic | Survey 1 N = 40 % (n) |

Survey 2 N = 34 % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 55 (22) | 53 (18) |

| Female | 45 (18) | 47 (16) |

| Race | ||

| White | 60 (24) | 62 (21) |

| African-American | 38 (15) | 35 (12) |

| Other | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 98 (39) | 97 (33) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Age | ||

| 45–49 | 8 (3) | 9 (3) |

| 50–59 | 38 (15) | 35 (12) |

| 60–69 | 50 (20) | 53 (18) |

| 70–74 | 5 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Education | ||

| Less than college grad | 33 (13) | 35 (12) |

| College grad/beyond | 68 (27) | 65 (22) |

| Household income | ||

| <$25 000 | 5 (2) | 6 (2) |

| $25 000–$49 999 | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| $50 000–74 999 | 10 (4) | 12 (4) |

| $75 000–$100 000 | 20 (8) | 18 (6) |

| >$100 000 | 63 (25) | 62 (21) |

| Received sequencing result? | ||

| Yes | 35 (14) | 41 (14) |

| No | 65 (26) | 59 (20) |

3.2 | Response rate for each round

Of the 162 participants invited to participate, 40 completed survey 1 with a response rate of 25%. Each item was completed by at least 38 participants. Of the 40 participants who answered survey 1, 34 participants completed survey 2 with a repeat response rate of 85%. Individuals who completed survey 2 were more likely to have received a genetic test result compared with those who did not complete survey 2 (P = .026). Each item in survey 2 was completed by at least 32 participants.

3.3 | Survey 1

Table 2 shows agreement fractions for each item of survey 1. Seven items on survey 1 were endorsed by less than 50% of participants and had a median less than “somewhat plausible.” Both items corresponding to change in identity were endorsed by <50% of the participants with only 34% supporting the notion that results would decrease one’s self-confidence and 40% endorsing the notion that results would negatively affect one’s self-identify. Items relating to concern over discrimination, concern about stigma, change in social support, moral concerns, and communications with relatives were endorsed by <50% of participants. These 7 items were removed from survey 2. The item “it could inform one’s plans for school or career” was endorsed by exactly 50% of participants and had a median rating between “somewhat plausible” and “somewhat implausible.” As such, this item was left on survey 2 as it could not definitively be excluded. In total, participants endorsed 28 items at the end of round one.

TABLE 2.

Agreement fraction and median for plausibility of each survey item

| Survey 1 | Survey 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Item | Agreement fraction (%) | Plausibility median | Agreement fraction (%) | Plausibility median |

| To enhance coping | ||||

|

| ||||

| Help one cope with one’s health risks | 100 | 3 | 85 | 6 |

|

| ||||

| Help one feel more in control of oneself | 84 | 3 | 71 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Help one feel more in control of one’s life situation | 80 | 3 | 64 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Mental preparation | ||||

|

| ||||

| Help one or one’s family mentally prepare for the future | 98 | 3 | 85 | 5.5 |

|

| ||||

| Give one a false sense of security | 77 | 3 | 52 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Feeling of responsibility | ||||

|

| ||||

| Alleviate feeling of responsibility for one’s children’s health risks | 61 | 3 | 46 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Spur feelings of responsibility for one’s children’s health risks | 75 | 3 | 65 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Improved spiritual well-being | ||||

|

| ||||

| Give one a greater sense of purpose in life | 72 | 3 | 49 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Help one live more fully | 85 | 3 | 58 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Value of information | ||||

|

| ||||

| Sequencing results are valuable simply because they provide information | 92 | 3 | 82 | 6 |

|

| ||||

| Sequencing results are valuable no matter what the results are | 100 | 3 | 67 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Knowledge of condition | ||||

|

| ||||

| Help one understand one’s health condition better | 100 | 4 | 90 | 7 |

|

| ||||

| Improve one’s self-knowledge | 100 | 3 | 85 | 6 |

|

| ||||

| Improve one’s understanding of one’s family | 85 | 3 | 82 | 6 |

|

| ||||

| Curiosity | ||||

|

| ||||

| Satisfy one’s curiosity | 98 | 3 | 72 | 6 |

|

| ||||

| Change in identity | ||||

|

| ||||

| Negatively affect one’s self-identify | 40 | 2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Decrease one’s self-confidence | 34 | 2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Feeling good for helping others | ||||

|

| ||||

| Make one feel good for contributing to research | 98 | 3 | 85 | 6 |

|

| ||||

| Make one feel good for providing knowledge to one’s family | 100 | 3 | 85 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Make one feel good for helping diffuse social problems | 62 | 3 | 33 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Concern over discrimination | ||||

|

| ||||

| Make one nervous about discrimination (insurance, employment) | 88 | 3 | 70 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Make one nervous about discrimination by other people | 46 | 2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Concern—privacy | ||||

|

| ||||

| Lead to an invasion of one’s privacy | 58 | 3 | 49 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Concern—stigma | ||||

|

| ||||

| Make one feel stigmatized by one’s peers | 48 | 2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Change in social support | ||||

|

| ||||

| Make one lose support from one’s friends and family | 25 | 2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Lead to greater support from one’s friends and family | 90 | 3 | 65 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Allow one to take advantage of social programs (advocacy) | 83 | 3 | 65 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Moral concerns | ||||

|

| ||||

| Spur moral concerns over eugenics or racism | 45 | 2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Ability for future planning | ||||

|

| ||||

| Motivate one to get one’s affairs in order | 90 | 3 | 68 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Allow one to organize long-term care | 95 | 3 | 74 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Inform one’s plans for school or career | 50 | 2.5 | 56 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Reproductive autonomy | ||||

|

| ||||

| Inform one’s decisions about having children | 83 | 3 | 79 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Use for prenatal testing to ensure children do not have condition | 95 | 3 | 79 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Communication with relatives | ||||

|

| ||||

| Spur increased communication with one’s family members | 82 | 3 | 68 | 5 |

|

| ||||

| Spur less communication with one’s family members | 35 | 2 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| Added items (survey 2) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Faith | ||||

|

| ||||

| Strengthen one’s faith | — | — | 32 | 4 |

|

| ||||

| Cast doubt on one’s faith | — | — | 18 | 3 |

Plausibility scale survey 1: 1 = very implausible; 2 = somewhat implausible; 3 = somewhat plausible; 4 = very plausible.

Plausibility scale survey 2: 1 = very implausible; 2 = implausible; 3 = somewhat implausible; 4 = neutral; 5 = somewhat plausible; 6 = plausible; 7 = very plausible.

Dash (–) indicates item not present in survey.

In responses to the open-ended questions, no participants reported that any items were unclear. Three participants commented that they saw themselves differently than the general population, one of whom reported that this made it challenging to predict how others might react to their own genome sequencing results. One participant commented that the absence of genome sequencing results could result in some of these outcomes, such as a “false sense of security.” One participant suggested additional items to include in survey 2. This suggestion referred to outcomes related to faith. Therefore, 2 items were added to survey 2: “strengthen one’s faith” and “cast doubt on one’s faith.”

3.4 | Survey 2

Based on the results from survey 1, survey 2 was created consisting of 30 items (7 were removed and 2 added). Except for the 2 added, items were identical to their appearance in survey 1.

The fraction of agreement for each item is shown in Table 2. Overall, 6 items were endorsed by <50% of participants. These included “alleviate feelings of responsibility for one’s children’s health risks,” “give one a greater sense of purpose in life,” “make one feel good for helping diffuse social problems such as racism,” “it could lead to an invasion of one’s privacy,” and the 2 items representing faith, which were added after survey 1. Items that were endorsed by <50% of participants and had a median less than “somewhat plausible” were removed from the final characterization of personal utility.

3.5 | Final results

Overall, 35 initial survey items representing 18 elements of personal utility were refined to 24 final items representing 14 elements. Elements that were dropped from surveys 1 and 2 to create this final characterization were: change in identity, concern over privacy, concern over stigma, and moral concerns. The scope of 6 other elements was refined by removal of 1 item from each element. Together, the Delphi process resulted in a final element list characterizing personal utility in genome sequencing. (Table 3)

TABLE 3.

Personal utility items endorsed in Delphi survey 2

| Final items of personal utility (corresponding element) | % Agree on | Plausibility median |

|---|---|---|

| • Help one understand one’s health condition better (knowledge of condition) | 90 | 6 |

| • Help one cope with one’s health risks (to enhance coping) | 85 | 6 |

| • Improve one’s self-knowledge (self-knowledge) | 85 | 6 |

| • Make one feel good for contributing to research (feeling good for helping others) | 85 | 6 |

| • Help one or one’s family mentally prepare for the future (mental preparation) | 85 | 5.5 |

| • Make one feel good for providing knowledge to one’s family (feeling good for helping others) | 85 | 5 |

| • Sequencing results are valuable simply because they provide information (value of information) | 82 | 6 |

| • Improve one’s understanding of one’s family (self-knowledge) | 82 | 6 |

| • Inform one’s decisions about having children (reproductive autonomy) | 79 | 5 |

| • Use for prenatal testing to ensure children do not have condition (reproductive autonomy) | 79 | 5 |

| • Allow one to organize long-term care (ability for future planning) | 74 | 5 |

| • Satisfy one’s curiosity (curiosity) | 72 | 6 |

| • Help one feel more in control of oneself (to enhance coping) | 71 | 6 |

| • Make one nervous about discrimination; insurance, employment (concern over discrimination) | 70 | 5 |

| • Motivate one to get one’s affairs in order (ability for future planning) | 68 | 5 |

| • Spur increased communication with one’s family members (communication with relatives) | 68 | 5 |

| • Sequencing results are valuable no matter what the results are (value of information) | 67 | 5 |

| • Spur feelings of responsibility for one’s children’s health risks (feeling of responsibility) | 65 | 5 |

| • Lead to greater support from one’s friends and family (change in social support) | 65 | 5 |

| • Allow one to take advantage of social programs; advocacy (change in social support) | 65 | 5 |

| • Help one feel more in control of one’s life situation (to enhance coping) | 64 | 5 |

| • Help one live more fully (improved spiritual well-being) | 58 | 5 |

| • Inform one’s plans for school or career (ability for future planning) | 56 | 5 |

| • Give one a false sense of security (mental preparation) | 52 | 4 |

Items are given in order of endorsement (high-low). Elements corresponding are in parentheses.

4 | DISCUSSION

The findings from this study contribute toward a growing body of evidence that individuals undergoing genome sequencing identify elements of personal utility as potential valued outcomes. The 6 items with the highest agreement fraction (at least 85%) reflect positive attributes of testing and none reflect harms. The top 6 endorsed items were: to help understand one’s “health condition” better, to help cope with one’s health risks, to improve one’s self-knowledge, to make one feel good for contributing to research, to make one feel good for providing knowledge to one’s family and to help one or one’s family mentally prepare for the future. These results contribute toward refining the scope of personal utility in the context of genome sequencing by identifying those elements most relevant to actual test users.

Most of the items removed through the Delphi process represented harms of genome sequencing. While not all negative outcomes were removed, their low endorsement by respondents reflects an overall positive appraisal of valued outcomes of genome sequencing. Our results are consistent with recent studies showing that participants in genome sequencing expect and experience several benefits and few risks from learning their results with regards to personal utility.5,19 Despite the low endorsement of negative outcomes in this study, it is important to acknowledge that some items were endorsed by at least 30% of participants and it may be important for researchers and healthcare providers to discuss these outcomes in pre-test contexts.

Negative outcomes described in the literature represent potential harms or the cost of personal utility. For example, a potential test taker may seek reassurance about genetic risk while recognizing that a false sense of security could arise. The latter is the consequence of more highly valuing peace of mind. Some individuals anticipate and may experience negative outcomes from genomic testing results, yet these outcomes do not themselves constitute personal utility. Rather, they represent risks of pursuing personal utility.

A thoughtful commentary by Bunnik et al distinguishes personal utility from perceived utility.20 They define the former as resulting from undergoing testing that yields clinically valid information that can provide non-health related benefits, while perceived utility describes perceptions that are based on test results that may or may not be clinically valid. This refines the definition of personal utility to exclude perceived utility of non-clinically valid test results to ensure that non-health related benefits originate from valid information. In our study, we did not specify a particular test result for participants to evaluate and as such, they did not account for the possibility for results to be of reduced clinical validity.

Using personal utility in clinical practice, such as in shared decision-making between genetic counselors and their clients, may benefit from a fuller understanding of the spectrum of patient-valued outcomes and thus use a broader scope of personal utility. Yet, when assessing the construct in large-scale evaluations of genomic tests for the purposes of informing regulatory decisions, policy guidelines, or public health interventions, orienting “utility” to positive or practical outcomes may be most meaningful. A next step to evaluating the elements of personal utility could consist of designing and assessing a scale for the concept.2

Psychological well-being outcomes have inconsistently been classified in the literature, with some investigators including them in assessment of clinical utility10,21 and others identifying them as outside the scope of “medically significant” outcomes.6,9 In our study, we adopted the former classification, that outcomes related to psychological well-being are components of clinical utility, and therefore excluded these outcomes from analysis. This decision was based on the numerous randomized controlled trials in cancer genetic testing that have included well-being as an outcome of clinical utility (Athens and Caldwell, in press).

This study has limitations. This Delphi analysis was based on a small number of participants (n = 40 and 34). This affects generalizability of the results to other research and clinical populations. In addition, despite efforts to capture diverse participant demographics, our participants were predominantly non-Hispanic, white, over 55 years old, highly educated, and of high socioeconomic status and thus, are not representative of the general population. The participants represent early adopters of technology15 and it is possible that people who have positive appraisals of personal utility self-select to enter a genome sequencing study. However, previous studies have found that this population is able to articulate complex concepts when probed for ideas, attitudes, and preferences surrounding genome sequencing.15 These characteristics are particularly useful for this study because it asks participants to consider a concept that is novel and complex. A final limitation pertains to understanding of the items. Items were taken directly from existing literature and, despite piloting of the survey, there is a possibility for items to be misinterpreted.

These data do not reflect the ideas and experiences of individuals who declined participation in The ClinSeq Project. This may introduce bias into the opinions gathered as part of this study. Further exploration is needed in populations that are knowledgeable about genome sequencing but have declined participation in research involving genome sequencing technologies because their initial motivations and expectations are likely to be related to their ultimate assessment of utility.

5 | CONCLUSION

This study is the first empirical effort to delineate elements of personal utility most relevant to participants in genome sequencing research. Items most highly endorsed by participants encompassed the following 4 elements: increased self-knowledge, knowledge of the condition, altruism, and anticipated coping. Our findings suggest that participants value personal gains associated with learning genome sequencing results. The 24 items identified in this study provide evidence for components of personal utility that can be used to frame future studies and inform clinical practice, particularly informed consent for genome sequencing. Additional studies to assess the generalizability of these findings will be important as genome sequencing is conducted more broadly.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

National Human Genome Research Institute Intramural Research Program.

This study was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute Intramural Research Program.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the National Human Genome Research Institute IRB Committee. Participants provided their initials and a unique identification number to access the survey, although responses were anonymous.

References

- 1.Biesecker LG, Green RC. Diagnostic clinical genome and exome sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2418–2425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1312543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster MW, Mulvihill JJ, Sharp RR. Evaluating the utility of personal genomic information. Genet Med. 2009;11:570–574. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181a2743e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravitsky V, Wilfond BS. Disclosing individual genetic results to research participants. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6:8–17. doi: 10.1080/15265160600934772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Facio F, Eidem H, Fisher T, et al. Intentions to receive individual results from whole-genome sequencing among participants in the ClinSeq study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21:261–265. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lupo PJ, Robinson JO, Diamond PM, et al. Patients’ perceived utility of whole-genome sequencing for their healthcare: findings from the MedSeq project. Per Med. 2016;13:13–20. doi: 10.2217/pme.15.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burke W, Atkins D, Gwinn M, et al. Genetic test evaluation: information needs of clinicians, policy makers, and the public. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:311–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holtzman NA, Watson MS. Promoting safe and effective genetic testing in the United States: final report of the task force on genetic testing. Clin Chem. 1999;45:732–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grosse SD, Khoury MJ. What is the clinical utility of genetic testing? Genet Med. 2006;8:448–450. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000227935.26763.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddow JE, Palomaki GE. ACCE: A Model Process for Evaluating Data on Emerging Genetic Tests. Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veenstra DL, Roth JA, Garrison LP, Ramsey SD, Burke W. A formal risk-benefit framework for genomic tests: facilitating the appropriate translation of genomics into clinical practice. Genet Med. 2010;12:686–693. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181eff533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veenstra DL, Piper M, Haddow JE, et al. Improving the efficiency and relevance of evidence-based recommendations in the era of whole-genome sequencing: an EGAPP methods update. Genet Med. 2013;15:14–24. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somerville JA. Corvallís, OR Recuperado. 2016. Effective Use of the Delphi Process in Research: Its Characteristics, Strengths and Limitations. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biesecker LG, Mullikin JC, Facio FM, et al. The ClinSeq Project: piloting large-scale genome sequencing for research in genomic medicine. Genome Res. 2009;19:1665–1674. doi: 10.1101/gr.092841.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis KL, Han PK, Hooker GW, Klein WM, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB. Characterizing participants in the ClinSeq genome sequencing cohort as early adopters of a new health technology. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohler J, Turbitt E, Biesecker BB. Personal utility in genomic testing: a systematic literature review. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.10. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buckner RL, Carroll DC. Self-projection and the brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heiko A. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2012;79:1525–1536. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halverson CM, Clift KE, McCormick JB. Was it worth it? Patients’ perspectives on the perceived value of genomic-based individualized medicine. J Community Genet. 2016;7:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s12687-016-0260-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunnik EM, Janssens AC, Schermer MH. Personal utility in genomic testing: is there such a thing? J Med Ethics. 2015;41:322–326. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2013-101887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institutes of Health. Enhancing the Oversight of Genetic Tests: Recommendations of the SACGT. 2000;2016 [Google Scholar]