Abstract

Background

This two-stage, phase IIa study investigated the antitumor activity and safety of MOR208, an Fc-engineered, humanized, CD19 antibody, in patients with relapsed or refractory (R-R) B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). CD19 is broadly expressed across the B-lymphocyte lineage, including in B-cell malignancies, but not by hematological stem cells.

Patients and methods

Patients aged ≥18 years, with R-R NHL progressing after ≥1 prior rituximab-containing regimen were enrolled into subtype-specific cohorts: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), other indolent (i)NHL and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Treatment was MOR208, 12 mg/kg intravenously, weekly, for 8 weeks. Patients with at least stable disease could continue treatment for an additional 4 weeks. Those with a partial or complete response after 12 weeks could receive extended MOR208 treatment (12 mg/kg, either monthly or every second week) until progression. The primary end point was overall response rate.

Results

Ninety-two patients were enrolled: DLBCL (n = 35), FL (n = 34), other iNHL (n = 11) and MCL (n = 12). Responses were observed in DLBCL, FL and other iNHL cohorts (26%, 29% and 27%, respectively). They lasted ≥12 months in 5/9 responding patients with DLBCL, 4/9 with FL and 2/3 with other iNHL. Responses in nine patients are ongoing (>26 months in five instances). Patients with rituximab refractory disease showed a similar response rate and progression-free survival time to patients with non-refractory disease. The most common adverse events (any grade) were infusion-related reactions (12%) and neutropenia (12%). One patient experienced a grade 4 infusion-related reaction and eight patients (9%) experienced grade 3/4 neutropenia. No treatment-related deaths were reported.

Conclusions

MOR208 monotherapy demonstrated promising clinical activity in patients with R-R DLBCL and R-R FL, including in patients with rituximab refractory tumors. These efficacy data and the favorable safety profile support further investigation of MOR208 in phase II/III combination therapy trials in R-R DLBCL.

ClinicalTrials.gov number

Keywords: CD19, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, MOR208, NHL, rituximab refractory

Key Message

This phase IIa study demonstrated the promising clinical activity and favorable safety profile of the Fc-engineered, humanized, CD19 monoclonal antibody, MOR208, in adult patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) who had received at least one prior rituximab-containing regimen. These data provide a rationale for further development of MOR208 in NHL.

Introduction

The B-lymphocyte antigen CD19 is expressed throughout B-cell development until terminal plasma cell differentiation [1]. Expression is not seen in stem cells or most other normal cell types. CD19 enhances B-cell antigen receptor signaling by amplification of phosphoinositide-3-kinase and Bruton’s tyrosine kinase activity [1, 2], which plays a crucial role in tumor cell proliferation and survival [3]. CD19 is broadly and homogeneously expressed across different B-cell malignancies including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [4, 5]. It has also been shown that expression is preserved during lymphoma treatment [6, 7]. Taken together, these characteristics suggest that CD19 represents an attractive target antigen in patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL).

MOR208 (XmAb®5574, MOR00208) is an Fc-engineered, humanized, CD19 monoclonal antibody. The Fc enhancement, comprising the introduction of S239D and I332E amino acid substitutions, leads to a potentiation of antigen-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and antigen-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis compared with the unmodified parental immunoglobulin G1 CD19 antibody, as demonstrated through in vitro and in vivo analyses in leukemia and lymphoma model systems. MOR208 also directly induces cytotoxicity, potentially by disrupting B-cell antigen receptor signaling [8, 9]. A phase I dose-escalation study in 27 patients with relapsed or refractory (R-R) CLL showed MOR208 to be safe and well tolerated and provided initial evidence of clinical activity; the highest tested intravenous dose of 12 mg/kg was recommended for phase II studies [10].

This phase IIa study was designed to investigate the antitumor activity of single-agent MOR208 in adult patients with R-R B-cell NHL who had received at least one prior rituximab-containing regimen.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

This is an open-label, single-arm, multicenter phase IIa trial with a two-stage design. Patients aged ≥18 years with histologically confirmed DLBCL, FL, other indolent (i)NHL or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), which had progressed after at least one prior cycle of a rituximab-containing regimen (defined as rituximab plus chemotherapy or at least four weekly administrations of single-agent rituximab), were eligible (for full criteria, see supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). Data on tumor expression levels of CD19 and CD20, and cell of origin for cases of DLBCL, were not available at the time of enrollment. Patients were considered to have rituximab refractory disease if they had no response, or a response lasting <6 months, to a prior rituximab-containing therapy.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating center and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before the initiation of any study-related procedure.

Treatment comprised MOR208 12 mg/kg, administered as an intravenous infusion over 2 h on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 of a 28-day cycle, for two cycles (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). After 8 weeks of dosing, patients with a partial or complete response or stable disease could continue for one additional cycle (i.e. 12 weeks of dosing overall). Patients with a documented partial or complete response at the end of cycle 3 could continue to receive MOR208 as extended treatment at a dose of 12 mg/kg, with the frequency of administration decided by the investigator, as either monthly or every second week, until disease progression or the occurrence of unacceptable toxicity. This flexibility in extended treatment scheduling allowed for investigator optimization according to lymphoma subtype and other clinical considerations.

For the first three MOR208 infusions in cycle 1, there was a mandatory prophylactic premedication [optional thereafter if no infusion-related reaction (IRR) occurred] including antipyretics, histamine H1 receptor blockers and glucocorticosteroids (methylprednisolone 80–120 mg intravenously or equivalent).

Study assessments

The primary end point was the overall response rate (sum of partial and complete responses), as assessed by the investigators according to the International Working Group criteria [11] (for the detail of investigator and central assessments, see supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). Adverse events (AEs), assessed continuously throughout the treatment, were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 15.1, and graded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

Serial blood samples were collected for pharmacokinetic, immunogenicity and biomarker analyses. Peripheral B-, T- and natural killer (NK) cell counts were assessed locally by flow cytometry. Additionally, if patients consented to FCGR2A/FCGR3A genotype analyses, a mucosal cheek swab was taken for DNA extraction. Genotyping was carried out by dideoxysequencing of polymerase chain reaction-amplified products (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany).

Statistical considerations

The primary end point, overall response rate, was assessed in the modified intent-to-treat (mITT) population, comprising all patients who received at least one dose of study drug (same definition for the safety population). Patients without any post-baseline response assessment were to be included as non-responders. Secondary end points included duration of response, progression-free survival (PFS), proportion of patients with stable disease, safety, pharmacokinetics and the immunogenicity of MOR208.

A two-stage design was used to minimize exposure of patients with NHL subtypes not responding to MOR208. In stage 1, ≥10 patients were to be enrolled into each of four NHL subtype-specific cohorts; DLBCL, FL, other iNHL and MCL. If ≥2 patients (20%) in a cohort had a partial or complete response after 8–12 weeks of treatment, then ≥20 additional patients with that NHL subtype were to be enrolled. The planned sample size was consequently between 40 and 120 patients. No formal statistical hypothesis testing was planned. For the post hoc PFS subgroup analysis of high versus low peripheral NK cell counts at baseline, the variable cut-off was determined by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis.

Results

Patients

Between 23 April 2013 and 4 November 2014, 92 patients were enrolled, including 35 with DLBCL, 34 with FL, 11 with other iNHLs (nine with marginal zone lymphoma; two with CLL), and 12 with MCL. The patient disposition is summarized in supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. Baseline characteristics showed a heavily pretreated population, with more than half of patients having rituximab refractory disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient and disease characteristics

| Characteristica | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma subtype cohort |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | FL | Other iNHL | MCL | Total | |

| N = 35 | N = 34 | N = 11b | N = 12 | N = 92 | |

| Age, years | |||||

| Median | 71 | 62 | 73 | 64.5 | 66.5 |

| Range | 35–90 | 40–87 | 45–83 | 56–74 | 35–90 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 24 (69) | 16 (47) | 5 (45) | 11 (92) | 56 (61) |

| Female | 11 (31) | 18 (53) | 6 (55) | 1 (8) | 36 (39) |

| ECOG PS | |||||

| 0 | 19 (54) | 22 (65) | 9 (82) | 6 (50) | 56 (61) |

| 1 | 15 (43) | 10 (29) | 2 (18) | 5 (42) | 32 (35) |

| 2 | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 0 | 1 (8) | 4 (4) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 33 (94) | 32 (94) | 11 (100) | 11 (92) | 87 (95) |

| Other | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 0 | 1 (8) | 5 (5) |

| Ann Arbor stage | |||||

| Stages I–II | 4 (11) | 5 (15) | 0 | 1 (8) | 10 (11) |

| Stages III–IV | 30 (86) | 29 (85) | 11 (100) | 11 (92) | 81 (88) |

| Unknown | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| International prognostic indexc | |||||

| High risk | 19 (54) | 10 (29) | – | 9 (75) | – |

| Low risk | 15 (43) | 23 (68) | – | 3 (25) | – |

| Missing | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | – | 0 | – |

| Prior lines of therapy | |||||

| 1 | 12 (34) | 13 (38) | 3 (27) | 3 (25) | 31 (34) |

| 2 | 8 (23) | 4 (12) | 2 (18) | 1 (8) | 15 (16) |

| 3 | 9 (26) | 5 (15) | 2 (18) | 2 (17) | 18 (20) |

| >3 | 6 (17) | 12 (35) | 4 (36) | 6 (50) | 28 (30) |

| DoR to most recent treatment | |||||

| ≤12 months | 26 (74) | 17 (50) | 8 (73) | 7 (58) | 58 (63) |

| >12 months | 3 (9) | 15 (44) | 3 (27) | 4 (33) | 25 (27) |

| Unknown | 6 (17) | 2 (6) | 0 | 1 (8) | 9 (10) |

| Time since last therapy | |||||

| ≤3 months | 16 (46) | 6 (18) | 3 (27) | 5 (42) | 30 (33) |

| >3 months | 19 (54) | 28 (82) | 8 (73) | 7 (58) | 62 (67) |

| Rituximab refractoryd | |||||

| Yes | 24 (69) | 17 (50) | 5 (45) | 6 (50) | 52 (57) |

| No | 11 (31) | 17 (50) | 6 (55) | 6 (50) | 40 (43) |

| Off rituximab >6 months | |||||

| Yes | 21 (60) | 29 (85) | 10 (91) | 11 (92) | 71 (77) |

| No | 14 (40) | 5 (15) | 1 (9) | 1 (8) | 21 (23) |

| Prior autologous stem cell transplant | 4 (11) | 6 (18) | 2 (18) | 1 (8) | 13 (14) |

| FCGR2A codon 131 statuse | |||||

| HH | 11 (31) | 9 (26) | 1 (9) | 3 (25) | 24 (26) |

| HR | 9 (26) | 13 (38) | 4 (36) | 6 (50) | 32 (35) |

| RR | 12 (34) | 3 (9) | 2 (18) | 1 (8) | 18 (20) |

| Missing | 3 (9) | 9 (26) | 4 (36) | 2 (17) | 18 (20) |

| FCGR3A codon 158 statusf | |||||

| VV | 5 (14) | 4 (12) | 0 | 1 (8) | 10 (11) |

| FV | 10 (29) | 12 (35) | 2 (18) | 6 (50) | 30 (33) |

| FF | 17 (49) | 9 (26) | 5 (45) | 3 (25) | 34 (37) |

| Missing | 3 (9) | 9 (26) | 4 (36) | 2 (17) | 18 (20) |

Data are number of patients (%) unless otherwise stated.

As determined at screening or at baseline.

Including nine patients with marginal zone lymphoma and two with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Assessed according to lymphoma subtype-specific scoring systems: DLBCL, International Prognostic Index; FL, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index; MCL, Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index.

Patients were considered rituximab refractory if they had no response or a response lasting <6 months to a prior rituximab-containing therapy.

Due to a single nucleotide polymorphism, codon 131 of the autosomal FCGR2A gene codes for either histidine (H) or arginine (R).

Due to a single nucleotide polymorphism, codon 158 of the autosomal FCGR3A gene codes for either valine (V) or phenylalanine (F).

DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DoR, duration of response; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FL, follicular lymphoma; iNHL indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma.

Efficacy

Based on responses in stage I, both the DLBCL and FL cohorts were expanded in stage 2 to 35 and 34 patients, respectively. Responses (two complete, one partial) were also seen for three patients with marginal zone lymphoma of 11 patients enrolled in the other iNHL cohort. However, due to the underlying heterogeneity of other iNHL subtypes, this cohort was not expanded. No responses were reported for 12 patients in the MCL cohort, and enrollment was stopped as per study design; stable disease was reported for six (50%) of these patients.

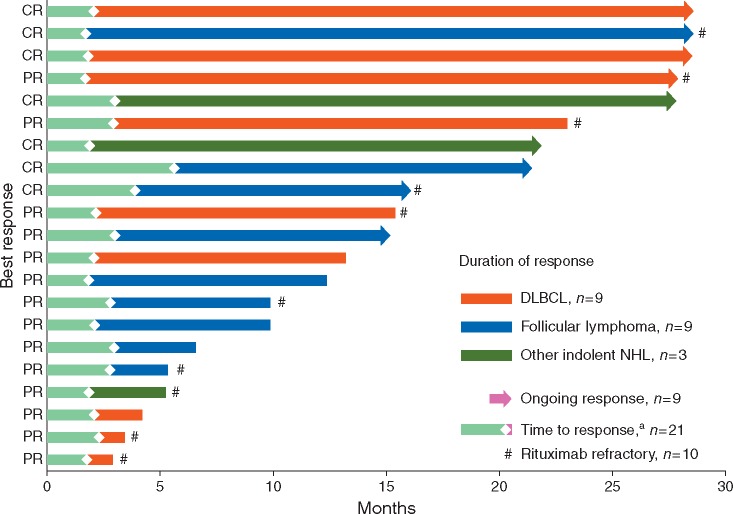

After the completion of stage 2, responses were seen in 9 (26%) of 35 patients (two complete, seven partial) in the DLBCL cohort and 10 (29%) of 34 patients (three complete, seven partial) in the FL cohort (Table 2), with a median time to response of 2.0 and 2.8 months for DLBCL and FL, respectively (Figure 1). Stable disease was reported for a further 5 (14%) and 16 (47%) patients, respectively. Sixteen out of 92 patients (17%) discontinued treatment before the first post-baseline radiological tumor assessment with unconfirmed disease progression and were counted as non-responders, including 10 of 35 (29%) with DLBCL. Among patients with rituximab refractory disease, the response rate was 21% (5/24 patients) in DLBCL, 24% (4/17) in FL and 20% (1/5) in other iNHL.

Table 2.

Investigator assessed best overall response

| DLBCL | FL | Other iNHL | MCL | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 35 | N = 34 | N = 11 | N = 12 | N = 92 | |

| Best overall response | |||||

| Complete response | 2 (6) | 3 (9) | 2 (18) | 0 | 7 (8) |

| Partial response | 7 (20) | 7 (21) | 1 (9) | 0 | 15 (16) |

| Stable disease | 5 (14) | 16 (47) | 4 (36) | 6 (50) | 31 (34) |

| Progressive disease | 11 (31) | 4 (12) | 3 (27) | 5 (42) | 23 (25) |

| Not evaluablea | 10 (29) | 4 (12) | 1(9) | 1 (8) | 16 (17) |

| ORR (all patients) | 9 (26) | 10 (29) | 3 (27) | 0 | 22 (24) |

| ORR (assessable patients onlyb) | 9 (36) | 10 (33) | 3 (30) | 0 | 22 (29) |

| DCR (all patients) | 14 (40) | 26 (76) | 7 (64) | 6 (50) | 53 (58) |

Data are number of patients (%).

Radiological post-baseline response assessment not performed/data unavailable.

Post hoc sensitivity analysis excluding patients without post-baseline radiological tumor assessment.

DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; DCR, disease control rate (complete + partial responses + stable disease); FL, follicular lymphoma; iNHL, indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; ORR, objective response rate (complete + partial responses).

Figure 1.

Time to and duration of response. aOne patient with stable disease had a late response (PR) after 17 months in follow-up. Outcome for this patient is not shown in the figure. CR, complete response; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; PR, partial response.

Tumor shrinkage data were available for central radiology assessment for 23 patients with DLBCL, 29 with FL and 7 with other iNHLs. The percentage change in indicator lesion size from baseline for individual patients during the course of the study is shown in supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online and the best change illustrated in supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online. These measurements demonstrated that initial partial responses could deepen over the course of the treatment. A degree of target lesion shrinkage was also apparent in 19 of 23 patients with stable disease (5 with DLBCL, 11 with FL and 3 with other iNHLs).

Responses were seen across all patient subgroups defined by FCGR2A codon 131 genotypes and FCGR3A codon 158 genotypes (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Duration of response and PFS

The median duration of response was 20.1 months (range 1.1–26.5) for DLBCL and not yet reached (range 2.6–26.6 months) for FL. Responses lasting ≥12 months were observed in five patients with DLBCL, four with FL and two with other iNHL (Figure 1). At the cut-off date, three patients with DLBCL, four with FL and two with iNHL were still in remission and on study treatment. Of the 10 responders with rituximab refractory disease (eight with partial and two with complete responses), six had a response duration of ≥10 months (26.0, 20.1 and 13.2 months in the DLBCL cohort; 10.6, 12.0 and 26.6 in the FL cohort).

With a median follow-up time of 21 months, the median PFS was 2.7 months (95% CI 2.1–15.4) in patients with DLBCL, 8.8 months (95% CI 5.3–27.1) in patients with FL and not reached (95% CI 2.0–NA) in patients with other iNHL (supplementary Figure S5A–C, available at Annals of Oncology online). The 12-month PFS rate was 39% in the DLBCL and FL subgroups. Notably, PFS was similar in patients with rituximab non-refractory versus rituximab refractory tumors [median 6.6 versus 5.3 months, respectively, hazard ratio (HR) 0.87, 95% CI 0.47–1.60, P = 0.67; supplementary Figure S5D, available at Annals of Oncology online]. Exploratory post hoc analysis revealed that patients with a baseline peripheral NK cell count above a threshold of 100 cells/µl (n = 36) had longer PFS compared with those below the threshold (n = 15; median 8.8 versus 2.3 months, respectively, HR 0.17, 95% CI 0.06–0.45, P = 0.0004).

Safety

The most frequently reported treatment-emergent AEs of any grade were IRRs and neutropenia, both occurring in 11 (12%) of 92 patients (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). All IRRs except one were non-serious events of grade 1 or 2. One patient (FL subgroup) experienced an IRR of grade 4 dyspnea, which was classified as a serious adverse event (SAE). This resolved, but the patient did not receive further study medication as per study protocol. Almost all IRRs [9 (82%) of 11 patients] occurred during the first MOR208 infusion; all patients recovered after the infusion was paused and symptomatic treatment was administered, allowing completion of infusions (except for the patient with grade 4 dyspnea).

The most common grade ≥3 AEs are summarized in Table 3. Hematological grade ≥3 AEs were more common in the DLBCL subgroup. The most frequently reported grade ≥3 AE was neutropenia [6 (17%) of 35 patients with DLBCL and 2 (6%) of 34 patients with FL]. None of the grade ≥3 neutropenia events were deemed to be SAEs by investigators. In most cases, they started during cycle 1 or 2 [6 (75%) of 8 patients] and all patients recovered within 1 week. Temporary interruption of MOR208 infusion was required in one patient who developed a grade 4 neutropenia. The majority of patients in the DLBCL subgroup developing neutropenia had a lymphocyte or neutrophil count below the lower limit of the normal reference range at baseline.

Table 3.

Treatment-emergent adverse events at grade ≥3 and IRR incidence according to grade

| TEAEs,an (%) | DLBCL | FL | Other iNHL | MCL | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 35 | N = 34 | N = 11 | N = 12 | N = 92 | |

| Any grade ≥3b | 19 (54) | 9 (27) | 5 (46) | 4 (33) | 37 (40) |

| Hematologicalc | |||||

| Neutropenia | 6 (17) | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 | 8 (9) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (8) | 4 (4) |

| Anemia | 3 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Non-hematologicalc | |||||

| Dyspnea | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 (8) | 4 (4) |

| Pneumoniad | 3 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (3) |

| Fatigue | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Hypokalemia | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Infusion-related reaction,an (%) | |||||

| Any | 4 (11) | 4 (12) | 1 (9) | 2 (17) | 11e (12) |

| Grade 1/2 | 4 (11) | 3 (9) | 1 (9) | 2 (17) | 10 (11) |

| Grade 4 | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

Data are number of patients (%).

TEAEs according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities preferred term (PT).

TEAEs including PT disease progression.

TEAEs reported at grade ≥3 in two or more patients overall.

In two patients, pneumonia started during the extended treatment phase (days 706 and 468, respectively), both patients recovered within 2 weeks. One patient developed pneumonia with cardiorespiratory failure (unrelated to MOR208 treatment) in cycle 1 (day 23) with a fatal outcome.

No grade 3 or grade 5 infusion-related reactions were reported.

DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; iNHL, indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; TEAEs, treatment emergent adverse events.

The most frequently reported grade ≥3 non-hematological AEs were dyspnea and pneumonia. One dyspnea (grade 4) event, also reported as an IRR, was assessed as related to MOR208. All three cases of pneumonia were in the DLBCL subgroup and were reported as not related to MOR208. The majority of patients who completed ≥3 treatment cycles [37 (76%) of 49 patients, 40% overall] did not experience any grade ≥3 AEs.

Four (4%) of 92 patients experienced an SAE with a suspected relationship to MOR208, two in the DLBCL subgroup (febrile neutropenia; genital herpes) and two in the FL subgroup [dyspnea; myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS; relationship to prior therapies could not be excluded)]. Three (3%) of 92 patients discontinued MOR208 due to treatment-related AEs. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Pharmacokinetics and immunogenicity

The mean terminal elimination half-life of MOR208 was approximately 16 days. The estimated steady state was reached after 40–50 days, with mean steady-state Cmax and trough levels of ∼500 and ∼250 µg/ml, respectively. Anti-drug antibodies were detected during treatment in only 1/92 patients (1%), indicating very low immunogenicity for MOR208.

Discussion

This study provides encouraging results for MOR208 monotherapy in patients with R-R NHL. Objective responses, including complete responses, were seen in 26% of patients with DLBCL and 29% with FL. Responses were in many cases durable, as shown by median durations of 20.1 months for DLBCL and not yet reached for FL and other iNHL, with the longest durations of response in each of subgroup being >2 years. It was recommended that glucocorticosteroids should be administered as a part of premedication to prevent IRRs. In view of the weekly frequency of premedication during the initial cycles, a potential contribution of corticosteroids to treatment efficacy cannot be ruled out. Thereafter, however, corticosteroids may have been administered at a maximum of once or twice monthly and thus, their contribution to the long-term antitumor effect of MOR208 is considered to be negligible. In addition, the observed target lesion shrinkage in most patients with a best objective response of stable disease suggests a therapeutic benefit, especially in patients with iNHL. Although the design of the current study with a maximum treatment period of 3 months for patients with stable disease was appropriate for an initial signal-seeking trial, extending MOR208 treatment until progression should be investigated in future clinical studies.

Notably, responses were seen in 10 (22%) of 46 patients with rituximab refractory disease, indicating the potential of alternatively targeting CD19 to improve outcome in such patients. Other CD19-targeted agents in clinical development include the CD19 antibody-drug conjugate, coltuximab ravtansine, the bispecific T-cell engaging CD19 antibody, blinatumomab and several anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell products. In phase I studies, responses were reported in 7 (28%) of 25 patients with R-R NHL treated with q1w/q2w coltuximab ravtansine [12], and 24 (69%) of 35 patients with R-R NHL treated with the recommended dose of blinatumomab [13]. In phase I/II CAR T-cell therapy trials, response rates of 59%–82% (including complete response rates of 43%–57%) have been reported in patients with R-R NHL [14–17]. Of note, markedly longer durations of response were noted for patients with complete compared with partial responses [14, 16]. However, the T-cell-based therapies are associated with relatively high levels of toxicity, including severe neurological events and cytokine release syndrome [13–17], raising the possibility that such approaches might be most appropriate for younger, fitter patients treated at specialist centers. Further studies will be required to determine the optimum patient populations for the different CD19-targeted agents.

NK cell-mediated ADCC is predicted to be an important component of the mode of action of MOR208. In line with this prediction, PFS was found to be longer in patients with an NK cell count above a threshold of 100 cells/µl.

MOR208 therapy was generally very well tolerated. The higher incidence of hematological AEs in the DLBCL subgroup is most likely attributable to the aggressive nature of this NHL subtype and shorter time period since the completion of the last treatment when compared with iNHL subtypes. Several of these heavily pretreated patients had baseline neutrophil counts below the lower limit of the normal reference range, probably as a result of their most recent antilymphoma therapy. There were few grade ≥3 non-hematological AEs. IRRs were typically mild, and mostly occurred during the first infusion.

The tolerability of MOR208 provides a rationale for combination studies, especially in elderly patients or those unsuitable for high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell transplantation. Importantly in this context, MOR208 has shown synergistic potential in preclinical experimental models with the immunomodulatory agent, lenalidomide and the cytotoxic alkylating nitrogen mustard, bendamustine [18]. Consequently, MOR208 is currently being investigated in patients with R-R DLBCL in a phase II study in combination with lenalidomide (L-MIND; NCT02399085), and in a phase II/III study, in combination with bendamustine (B-MIND, NCT02763319). On the basis of preliminary encouraging results for MOR208 plus lenalidomide in the L-MIND study, [19] MOR208 has now been designated as a breakthrough therapy for R-R DLBCL by the US Food and Drug Administration.

In conclusion, single-agent MOR208 showed promising activity with long-lasting responses in aggressive and iNHL subtypes, including in patients with rituximab refractory disease. Based on these data, and the favorable safety and tolerability of MOR208, further clinical development of combination therapy with MOR208 is now being undertaken in patients with B-cell malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families and the clinical staff at all participating centers. Medical writing assistance was provided by Jim Heighway PhD, Cancer Communications and Consultancy Ltd, Knutsford, UK and was funded by MorphoSys AG.

Funding

MorphoSys AG (no grant number is applicable).

Disclosure

WJ has compensated consultancy/advisory roles with MorphoSys AG, Teva, Celgene, Abbvie and Sandoz-Novartis and has received research funding from MorphoSys AG, Novartis, Pfizer, Gilead, Janssen, Celltrion, Bayer, Takeda, Servier, Teva, Roche and AstraZeneca; PLZ has compensated consultancy advisory roles with Morphosys AG, Sandoz, Celgene, Roche, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Gilead, Servier, Celltrion, Verastem; GG has consultancy/advisory roles and has received honoraria from MorphoSys AG, Roche, Janssen, Gilead, Amgen and Novartis and has had travel/accommodation/other expenses reimbursed by MorphoSys AG, Janssen, Gilead, Amgen; AG has received honoraria from Celgene, Takeda, Pharmacyclics, Johnson & Johnson and Acerta, has compensated consultancy/advisory roles with Celgene, Takeda, Pharmacyclics, Johnson & Johnson, Acerta and Infinity, has participated in speaker’s bureaus for Takeda, Pharmacyclics and Johnson & Johnson, has received writing support from Takeda and his institution has received research funding from Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Johnson & Johnson and Genentech; TR has received honoraria and research funding from, and has a consulting/advisory role with MorphoSys AG; KM has compensated consultancy/advisory roles with Seattle Genetics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pharmacyclics and Janssen and has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pharmacyclics; CB has received honoraria from Roche, Janssen, Gilead and Pfizer and research funding from Roche and Janssen; SA, MW, MD-H and RK are salaried employees of MorphoSys AG and MW has an intellectual property interest relating to MorphoSys AG; KAB’s institution has received research funding from MorphoSys AG, Constellation, Celgene, Novartis, Janssen and Millennium. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Wang K, Wei G, Liu D.. CD19: a biomarker for B cell development, lymphoma diagnosis and therapy. Exp Hematol Oncol 2012; 1(1): 36.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fujimoto M, Poe JC, Inaoki M, Tedder TF.. CD19 regulates B lymphocyte responses to transmembrane signals. Semin Immunol 1998; 10: 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seda V, Mraz M.. B-cell receptor signalling and its crosstalk with other pathways in normal and malignant cells. Eur J Haematol 2015; 94(3): 193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olejniczak SH, Stewart CC, Donohue K, Czuczman MS.. A quantitative exploration of surface antigen expression in common B-cell malignancies using flow cytometry. Immunol Invest 2006; 35(1): 93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schuurman HJ, Huppes W, Verdonck LF. et al. Immunophenotyping of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Correlation with relapse-free survival. Am J Pathol 1988; 131: 102–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hiraga J, Tomita A, Sugimoto T. et al. Down-regulation of CD20 expression in B-cell lymphoma cells after treatment with rituximab-containing combination chemotherapies: its prevalence and clinical significance. Blood 2009; 113(20): 4885–4893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamburova EG, Koenen HJ, Joosten I, Hilbrands LB.. CD19 is a useful B cell marker after treatment with rituximab: comment on the article by Jones et al. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65(4): 1130–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Awan FT, Lapalombella R, Trotta R. et al. CD19 targeting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with a novel Fc-domain-engineered monoclonal antibody. Blood 2010; 115(6): 1204–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horton HM, Bernett MJ, Pong E. et al. Potent in vitro and in vivo activity of an Fc-engineered anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody against lymphoma and leukemia. Cancer Res 2008; 68(19): 8049–8057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woyach JA, Awan F, Flinn IW. et al. A phase 1 trial of the Fc-engineered CD19 antibody XmAb5574 (MOR00208) demonstrates safety and preliminary efficacy in relapsed CLL. Blood 2014; 124(24): 3553–3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME. et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(5): 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ribrag V, Dupuis J, Tilly H. et al. A dose-escalation study of SAR3419, an anti-CD19 antibody maytansinoid conjugate, administered by intravenous infusion once weekly in patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2014; 20(1): 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goebeler ME, Knop S, Viardot A. et al. Bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody construct blinatumomab for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma: final results from a phase I study. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(10): 1104–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL. et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(26): 2531–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schuster S, Bishop M, Tam C. et al. Global pivotal phase 2 trial of the CD19-targeted therapy CTL019 in adult patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) – an interim analysis. Hematol Oncol 2017; 35: 27. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abramson J, Palomba M, Gordon L. et al. CR rates in relapsed/refractory (R/R) aggressive B-NHL treated with the CD19-directed CAR T-cell product JCAR017 (TRANSCEND NHL 001). J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(Suppl 15): Abstr 7513. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schuster SJ, Svoboda J, Chong EA. et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells in refractory B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(26): 2545–2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Winderlich M, Ness D, Steidl S, Endell J.. Evaluation of combination therapies with MOR00208, an Fc-enhanced humanized CD19 antibody, in models of lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(Suppl 15): Abstr 6574. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Salles G, Duell J, González-Barca E. et al. Single-arm phase II study of MOR208 combined with lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: L-MIND. Blood 2017; 130(Suppl 1): Abstr 4123. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.