Abstract

Complex II (SdhABCD) is a membrane-bound component of mitochondrial and bacterial electron transport chains, as well as of the TCA cycle. In this capacity, it catalyzes the reversible oxidation of succinate. SdhABCD contains the SDHA protein harboring a covalently bound FAD redox center and the iron–sulfur protein SDHB, containing three distinct iron–sulfur centers. When assembly of this complex is compromised, the flavoprotein SDHA may accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix or bacterial cytoplasm. Whether the unassembled SDHA has any catalytic activity, for example in succinate oxidation, fumarate reduction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, or other off-pathway reactions, is not known. Therefore, here we investigated whether unassembled Escherichia coli SdhA flavoprotein, its homolog fumarate reductase (FrdA), and the human SDHA protein have succinate oxidase or fumarate reductase activity and can produce ROS. Using recombinant expression in E. coli, we found that the free flavoproteins from these divergent biological sources have inherently low catalytic activity and generate little ROS. These results suggest that the iron–sulfur protein SDHB in complex II is necessary for robust catalytic activity. Our findings are consistent with those reported for single-subunit flavoprotein homologs that are not associated with iron–sulfur or heme partner proteins.

Keywords: structure-function, electron transfer complex, flavoprotein, mitochondrial respiratory chain complex, protein assembly, protein domain, protein evolution

Introduction

Complex II proteins serve essential cellular functions both as part of the TCA cycle and in oxidative phosphorylation (1, 2). The complex II soluble domain is a subcomplex comprised of SdhA (a free flavoprotein subunit of Escherichia coli SQR; ∼65–70 kDa)2 harboring a covalently bound FAD redox center and an iron–sulfur protein SdhB (∼27 kDa) containing three distinct iron–sulfur centers. This domain catalyzes the reversible oxidation of succinate at the FAD cofactor. Following complex II assembly, the SDHAB subcomplex is permanently associated with the membrane via two transmembrane subunits, SDHC (∼15 kDa) and SDHD (∼10–13 kDa). Together, these membrane anchor subunits ligate a b-type heme. Further an active site for quinone oxidoreduction is located at the interface of the SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD subunits (3–6).

Critical to the function of complex II is its correct assembly, and alteration of complex II assembly or activity has a number of clinical manifestation (7). Although the majority of disease-associated mutations of complex II have been found in the SDHB and SDHD genes (8), missense or nonsense mutations of either the structural subunits of the four identified assembly factors or eukaryotes (9–12) have been associated with pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma tumors, renal cell carcinomas, and gastrointestinal tumors (13–18). Many of these mutations result in severe assembly defects and lead to accumulation of the free SDHA flavoprotein in the mitochondrial matrix (9, 12).

Notably, when electron transport is impaired in intact complex II, the FAD cofactor can generate significant quantities of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (19–21). In a mouse model with a SDHC mutation, this oxidative stress causes neurological defects and increased tumorigenesis (22). It has been postulated that the unassembled flavinylated SDHA subunit may also be a source of ROS (11, 12). Although it has never been directly demonstrated whether unassembled SDHA has any catalytic activity or is associated with significant ROS generation, this could explain how the diseases associated with complex II misassembly might differ from those associated with assembled complex II containing missense mutations. Such information will be useful to differentiate whether a pathological phenotype is due to SDHA accumulation or cell wide consequences caused by impaired complex II activity.

It is well known that gammaproteobacteria such as E. coli encode two complex II homologs that are excellent model systems for the mitochondrial enzyme (2). Aerobically E. coli expresses succinate:quinone oxidoreductase (SQR, SdhABCD, bacterial complex II), whereas anaerobically a membrane-bound quinol fumarate reductase (QFR, FrdABCD) is utilized in the anaerobic respiratory chain with fumarate as the terminal electron acceptor. Many studies have shown that both models recapitulate the catalytic and structural properties of the mammalian enzyme (1–6, 23, 24).

Therefore, in the current communication, we have investigated the catalytic properties and ROS production by the free flavoprotein subunit of complex II. This information is lacking from either eukaryotic or prokaryotic sources. We have used as models for this study the human SDHA (hSDHA) flavoprotein and the E. coli SdhA and FrdA flavoproteins. Our findings suggest that the free flavoprotein of complex II is unlikely to be a significant source of ROS because of its inherently low catalytic activity.

Results

Isolation of the free flavoprotein subunits of complex II

To express E. coli SdhA or the FrdA flavoproteins in the absence of their other structural subunits, we took advantage of E. coli strain RP-2 (Table 1), which harbors a knockout of sdhCDAB and frdABCD. Plasmids pCA24N-SdhA and pCA24N-FrdA (Table 1) are then used to express and purify the soluble N-terminal His-tagged SdhA or FrdA subunits (Fig. 1A). To obtain human SDHA (herein noted as hSDHA) that could be used for catalytic analysis, we utilized a synthetic hSDHA gene sequence optimized for expression in E. coli. The optimized hSDHA was cloned into an expression vector (Table 1) and transformed into E. coli. In agreement with previous studies, we found that flavinylation of hSDHA is not supported by the E. coli flavinylation assembly factor SdhE and instead requires the human homolog of this assembly factor, SDHAF2 (9, 25). Therefore, we used a polycistronic expression vector to coexpress hSDHA and hSDHAF2 (Table 1) as described under “Experimental procedures.” When both proteins are coexpressed, a fully flavinylated His-tagged hSDHA protein can be visualized and isolated (Fig. 1A). The hSDHA protein was validated by MS and Western blotting analysis using a mAb against hSDHA. Interestingly, the isolated hSDHA protein remained tightly associated with hSDHAF2 (Fig. 1A). This protein complex is consistent with observations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae where a preassembly complex of ∼90 kDa consisting of yeast SdhA and Sdh5 (the homolog of SDHAF2) is observed (9). As shown in Fig. 1A, treating the hSDHA–SDHAF2 complex with 1 m guanidine hydrochloride removed greater than 85% of the associated assembly factor from the hSDHA flavoprotein. The detailed purification protocol is outlined under “Experimental procedures.”

Table 1.

E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Genotype/description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RP-2 | his thr leu metE thi eda rpsL; ΔsdhΔfrd | Ref. 35 |

| BL21Gold(DE3) | F−ompT dcm hsd (rB−mB−) gal λ (DE3) | Agilent |

| SoluBL21 | F− ompT hsdSB (rB−mB−) gal dcm (DE3) | Genlantis |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKJE7 | DnaK–DnaJ–GrpE, arab, CmR | Takara |

| pQE-80L | Expression vector for N-terminal His6-protein, AmpR | Qiagen |

| pCA24N-SdhA | N-terminal His6 tag, IPTG inducible, E. coli SdhA, Cmr | Ref. 73 |

| pCA24N-FrdA | N-terminal His6 tag, IPTG inducible, E. coli FrdA, Cmr | Ref. 73 |

| pFrdA | E. coli FrdA expression plasmid, FRD promoter, pBR322 based | Ref. 35 |

| pQE-hSDHA | SDHA expression vector, N-terminal His6, pQE-80L derivative, AmpR | This study |

| pQE-hSDHA/SDHAF2 | hSDHA/hSDHAF2 expression vector, polycistronic transcript under T5 promoter for His6-hSDHA, untagged hSDHAF2 downstream of hSDHA is connected via linker retaining ribosomal binding site, AmpR | This study |

Figure 1.

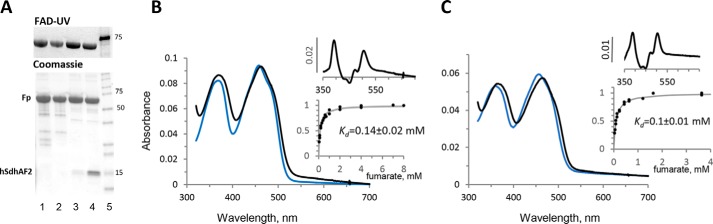

Purification of flavoproteins and spectra of hSdhA. A, SDS-PAGE comparison of purified hSDHA, E. coli SdhA, and FrdA preparations. Proteins were prepared as described under “Experimental procedures.” The left lane shows that the as-isolated hSDHA contains tightly bound SDHAF2. The identity of SDHAF2 was determined by MS. The third and fourth lanes show the E. coli SdhA and FrdA preparations, respectively. The top panel (FAD-UV) shows the in gel fluorescence, indicating the similar content of covalent FAD in human and bacterial flavoproteins. B, visible absorbance spectra of the hSDHA/SDHAF2 complex. The blue spectrum is the as-isolated complex, and the black spectrum is in the presence of 9 mm fumarate. The spectra were recorded in 50 mm BTP (pH 7.0). The concentration of hSDHA was 7.8 μm. The inset shows the fumarate induced difference spectrum. The lower inset shows the optical titration of fumarate binding using the absorbance at 505–451 nm as previously described (26). C, visible absorbance spectra of free hSDHA following guanidine HCl treatment. The spectrum of the ligand free hSDHA (5.2 μm) is shown (blue line) and in the presence of 4 mm fumarate (black line). The inset shows the fumarate induced difference spectrum (top) and the optical titration of fumarate binding using 508–455 nm (bottom).

Previously we had shown in the E. coli system, the binding of the covalent flavinylation chaperone SdhE to FrdA had only minor effects on the binding of fumarate to the protein (26). As shown in Fig. 1B, the as-isolated hSDHA–SDHAF2 complex demonstrates typical spectral characteristics (366 and 458 nm absorbance) of a flavin containing protein, and the spectra are not altered by removal of SDHAF2 (Fig. 1C). The insets in Fig. 1 (B and C) show difference spectra indicating that the addition of fumarate causes a spectral shift similar to that we previously found for E. coli FrdA or SdhA (26, 27). Also in agreement with our previous studies of FrdA (26), spectral titration of fumarate binding to hSDHA showed that hSDHA retains its interaction with substrate when bound to SDHAF2 (Kd = 140 μm; Fig. 1B) or when it is in its free form (Kd = 100 μm; Fig. 1C). Overall these data suggest that the heterologously expressed hSDHA protein is flavinylated and binds dicarboxylates similar to its bacterial counterparts.

Catalytic properties of the flavoprotein subunit of complex II

Succinate/fumarate interconversion by complex II enzymes is considered to be a reversible process (23, 28, 29). Catalysis is suggested to proceed via a hydride transfer between the N5 of the flavin and C3 of the substrate and proton exchange at the substrate C2 with a catalytic arginine (28, 30). Assembled mammalian complex II and the E. coli SQR and QFR homologs are all characterized by high rates of succinate oxidation with ubiquinone or artificial electron acceptors. Typically, the maximum dehydrogenase activity of complex II is determined with an electron mediator such as phenazine ethosulfate in the presence of a final electron acceptor like 2,6-dichloroindophenol (DCIP). The steady-state kinetic analysis of the purified mammalian and bacterial SdhA and FrdA flavoproteins showed a 300–1000-fold lower succinate dehydrogenase activity when compared with the corresponding fully assembled complexes (Table 2). The steady-state kcatapp of ∼0.15 s−1 was detected with DCIP as electron acceptor and was not stimulated in the presence of phenazine ethosulfate. The rates of the reactions remained the same under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions, indicating that there is no significant leak to oxygen during the reaction.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of isolated FrdA, SdhA, and membrane-bound SQR and QFR complexes

| Protein used | Succinate-DCIP reductase, kcatapp |

BV+-fumarate-reductase, activitya |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex II | Flavoprotein | Complex II | Flavoprotein | |

| s−1 | fum/s | |||

| Bovine mitochondrial | ||||

| Complex IIa | 111b | 2.7b | ||

| hSDHA | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | ||

| E. coli | ||||

| SQR | 102 ± 4c | 1.5 ± 0.1c | ||

| QFR | 27 ± 0.5c | 197 ± 3c | ||

| SdhA | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.13 ± 0.01 | ||

| FrdA | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | ||

a Activity was determined as described under “Experimental procedures” and corresponds to nmol fumarate/s per nmol flavoprotein (fum/s). Succinate-DCIP reductase and BV+-fumarate reductase activity data were determined at 30 °C and represents three separate independent analyses.

b Calculated for bovine heart complex II based on 6 nmol FAD/mg protein (74).

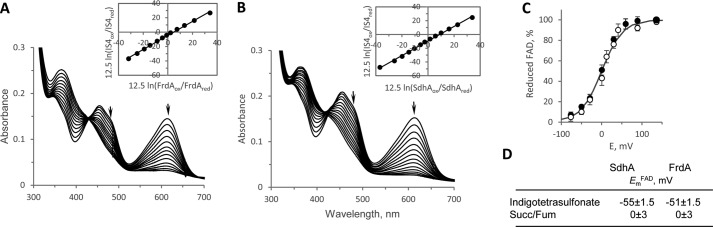

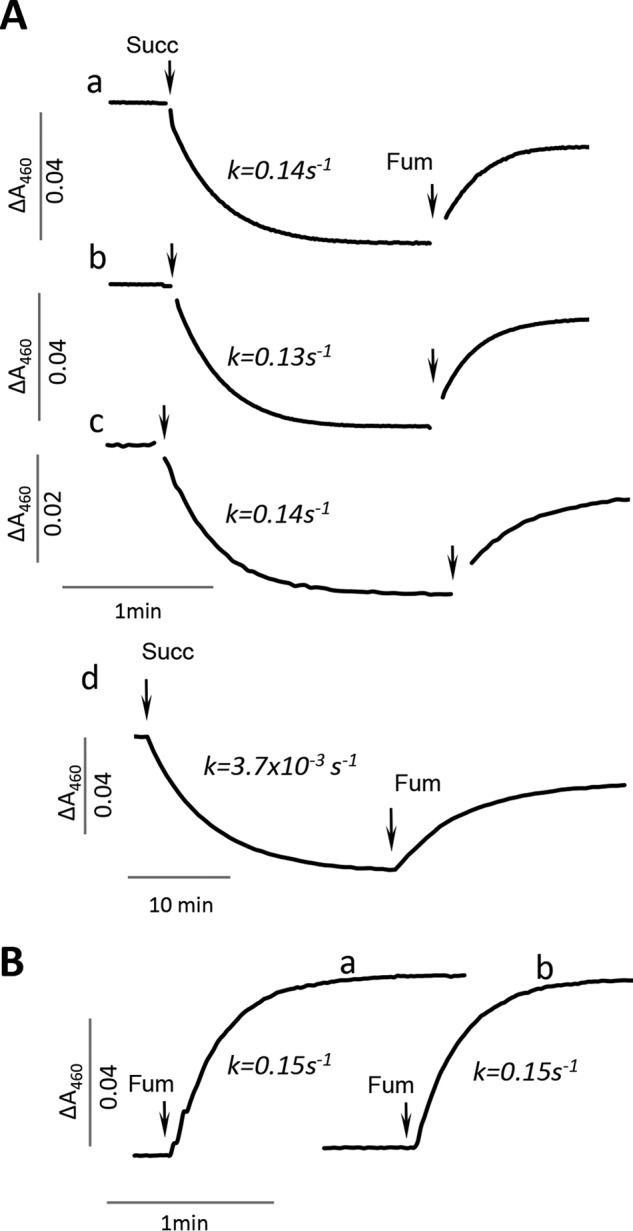

The rate of FAD reduction by succinate in assembled complex II enzymes is much faster than kcatapp and has never been reliably determined because of instrumental and experimental limitations (i.e. the mixing time exceeds the rate of FAD reduction and inherent difficulties in removing tightly bound oxaloacetate from the active site). Direct monitoring of flavin reduction in the unassembled flavoproteins is possible because of the lack of spectral interference from other complex II redox cofactors (i.e. iron–sulfur centers and b heme). Therefore we examined the direct reduction of FAD by succinate to investigate whether the low kcatapp was due to an inherent slow rate of reduction of the FAD or because DCIP is a poor electron acceptor for the unassembled flavoprotein. As shown in Fig. 2A, both bacterial and human flavoproteins are redox-active with succinate/fumarate as followed by optical changes of the flavin at 460 nm. The observed monophasic rates of FAD reduction by succinate in the flavoproteins were found to be similar (∼0.14 ± 0.02 s−1; Fig. 2A, panels a–c). Moreover, the rate constants were not affected when the reaction was performed under anaerobic conditions (data not shown). Fig. 2B demonstrates the reaction of fumarate reoxidation of the dithionite reduced bacterial FrdA and SdhA. This reaction was performed anaerobically as the dithionite-reduced form of the flavoproteins, which are free of dicarboxylates can be reoxidized by oxygen (i.e. when a dicarboxylate is present at the active site this reoxidation is inhibited (19, 20)). The observed rates of ∼0.15 ± 0.02 s−1 of flavin reoxidation by fumarate (Fig. 2, A and B) are also consistent with the steady-state rate of the BV+-fumarate reductase reaction (Table 2), indicating that in the unassembled flavoprotein the reaction of succinate-oxidation and fumarate-reduction are equally impaired.

Figure 2.

FAD reduction by succinate and fumarate reoxidation of complex II flavoproteins. A, panel a, time course of FAD reduction by succinate and fumarate reoxidation of E. coli SdhA. Activities were measured in 50 mm BTP, pH 8.0, at 30 °C, using succinate as electron donor followed by reoxidation with fumarate as described under “Experimental procedures.” The flavoprotein (10 μm) was reduced with 5 mm succinate and reoxidized with 5 mm fumarate. Panel b, time course of FAD reduction by succinate and fumarate reoxidation of E. coli FrdA. The assay conditions were identical to that described in panel a. Panel c, time course of FAD reduction by succinate and fumarate reoxidation of hSDHA free of SDHAF2. The assay conditions were identical to those described in panel a. Panel d, time course of FAD reduction by succinate and fumarate reoxidation of the hSDHA–SDHAF2 complex (4.6 μm hSDHA). Assay conditions were identical to that described in panel a except that 2 mm DTT was added to the assay. Note that the time scale of the measurement is 10-fold longer than the other assays consistent indicative of a 25-fold reduction in activity. B, line a, time course of fumarate (5 mm) reoxidation of the FADH2 of FrdA where the FAD was reduced by stoichiometric amounts of dithionite. Line b, time course of fumarate (5 mm) reoxidation of the reduced flavin where the FAD was reduced by stoichiometric amounts of dithionite.

ROS production by isolated complex II flavoproteins

Oxygen is known to react with reduced complex II and produce superoxide and H2O2. With succinate as an electron donor, mammalian and bacterial SQRs produce mostly superoxide with maximum rates at ∼50 μm succinate (20, 21). E. coli QFR emitted predominately superoxide at low and H2O2 at high succinate concentrations (19). FAD is the most plausible site for protein interaction with oxygen in these complexes based on the ability of high substrate concentrations to suppress reactive oxygen species formation (19–21). Thus, there is a high probability that the isolated reduced flavoproteins might be especially reactive with oxygen in the absence of the other subunits. Given that we observed a tight association between hSDHA and SDHAF2 (Fig. 1A) and previous observations in yeast (9), it is likely that in vivo hSDHA–SDHAF2 would be found in a complex in the mitochondrial matrix. Nevertheless, when testing whether the proteins could produce ROS, we assayed the purified hSDHA both essentially free of SDHAF2 and with tightly associated SDHAF2. We also compared the activity to what we observe for E. coli SdhA and FrdA. We found that there was no detectable reaction observed for either the bacterial or human isolated flavoproteins with acetylated cytochrome c, indicating a lack of detectable superoxide production. In contrast, all three proteins had low but detectable levels of H2O2 production with the highest rates observed at 50 μm succinate (Table 3). Higher concentrations of succinate suppressed this H2O2 production, as would be expected if the flavin is the site of oxygen reactivity (19). The hSDHA with tightly associated SDHAF2 also showed no detectable reaction with oxygen, which is not surprising because of the dramatic effect that this association has on FAD reduction by succinate (Fig. 2A, panel d). The unassembled flavoproteins are also highly overexpressed (∼10–20 mg protein/L-cell culture) without having any effect on cell growth. We also examined H2O2 production in E. coli cellular extracts where we added the purified FrdA or SdhA proteins to see whether there was an endogenous cellular component that might stimulate ROS formation. There was, however, no change in H2O2 production beyond the low basal H2O2 activity shown in Table 3 even with the addition of 50 μm to 2 mm succinate. Thus, it appears unlikely that the isolated flavoprotein subunit would be a major source of damaging ROS in situations where assembly is compromised.

Table 3.

Hydrogen peroxide production by the flavoprotein subunits of complex II

The reaction was measured at pH 8.0 at 30 °C with Amplex UltraRed as described under “Experimental procedures.” The data represent the mean of three independent measurements with the error within 10% of the values. ND, not detectable.

| Succinate | Activitya |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hSDHA |

E. coli |

|||

| −SDHAF2 | +SDHAF2 | SdhA | FrdA | |

| nmol/s per nmol flavoprotein | ||||

| 10 μm | 0.002 | ND | 0.003 | 0.005 |

| 50 μm | 0.003 | ND | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| 2000 μm | 0.001 | ND | 0.001 | 0.001 |

a Activity represents nmol H2O2/s per nmol flavoprotein.

Characterization of the flavoproteins

Because there seems to be no a priori reason for the flavoprotein subunits to have such a low catalytic activity, we next ruled out several reasons for this loss of catalysis. First, we investigated whether the flavoprotein subunits could be bound to an inhibitor molecule. Membrane-bound complex II, as isolated, contains a tightly bound dicarboxylate inhibitor (oxaloacetate) that must be removed to achieve maximal initial activity (31–33). The soluble domain of complex II (SdhAB/FrdAB), however, is isolated free of this metabolic inhibitor and does not require preactivation to achieve the full rate of catalysis (34). Each of the free flavoproteins, like soluble SdhAB or FrdAB, however, showed maximal activity as isolated. This would suggest that the dicarboxylate-binding site is free of bound inhibitor and that bound oxaloacetate is not the reason for the inherently lower activity.

Next, we questioned whether aspects of the construct were interfering with catalysis. The flavoproteins were constructed with an N-terminal His tag. Previous work showed that a His tag does not interfere with covalent flavinylation of the proteins (27, 35). This indicates that the proteins are folded correctly for interaction with the SdhE chaperone and that the His tag does not affect active site preorganization for self-catalytic FAD attachment (9, 11, 25, 27, 35). Nevertheless, we investigated whether the presence of the N-terminal His tag might be the reason for the low activity of the isolated flavoproteins. We thus compared the kinetic properties of the purified N-terminal His-tagged FrdA and WT untagged FrdA. The rationale for focusing on E. coli FrdA for this experiment is that WT FrdA is highly expressed anaerobically under control of the natural FRD promoter in E. coli RP-2 (Table 2) deleted for both frdABCD and sdhCDAB. The WT FrdA protein can also be purified by conventional ion exchange chromatography (27). Isolated WT FrdA shows the same rates for succinate oxidation and fumarate reduction as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2B as the His-tagged counterpart. The proteins were also equally stable from multiple freeze/thaw cycles and prolonged incubation at ambient temperature. These data suggest that N-terminal His tag does not affect the folding, covalent flavinylation, or catalytic properties of the flavoprotein. As a result, the low activity is likely an inherent property of all complex II flavoproteins in the absence of the other complex II subunits.

One factor that was important for analysis of catalytic activity in the unassembled flavoproteins was the presence of the chaperone involved in covalent flavin assembly. Consistent with previous findings for the effect of SdhE on catalytic activity of FrdA (26), we found that SDHAF2 inhibited flavin reduction and reoxidation by hSDHA (Fig. 2A, panel d). As noted in Fig. 1A, the as-isolated hSDHA protein was in a tight complex with SDHAF2 requiring mild chaotropes to separate the two proteins. The association between the hSDHA and SDHAF2 appears to be much stronger than binding of SdhE to the bacterial flavoproteins where this association has Kd values of 0.7 μm for bacterial FrdA and 1.5 μm for bacterial SdhA (26). Thus, one major difference between the bacterial and mammalian assembly factors is that the former is readily removed from the flavoprotein, whereas the mammalian complex is tightly bound.

Kinetic isotope and pH profiles of isolated FrdA and SdhA

In intact complex II catalysis includes the transfer of two protons between the substrate and the protein, as well as proton delivery from the bulk solvent to reprotonate the catalytic arginine. Therefore, because of the multiple sites anticipated to be involved in proton exchange, we investigated the pH dependence and kinetic isotope effects of the succinate dehydrogenase reaction. We had previously determined the pKa of the intact SQR and QFR complexes to be ∼7.5 with the rate enhanced as the pH increases (23). We found the same for the isolated SdhA and FrdA subunits, although the pKa had shifted to ∼8.0 for both flavoproteins (data not shown).

Previous studies of succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate reductase homologs have observed substrate and solvent kinetic isotope effects (36–38). Therefore, we compared the same parameters for the intact E. coli SQR and QFR complexes to that of the isolated SdhA and FrdA subunits. As shown from the data in Table 4, the substrate and solvent kinetic isotope effects show no significant differences for reactions catalyzed by SQR/QFR and SdhA/FrdA in the succinate dehydrogenase reaction. The high substrate isotope effect (∼5) in both the intact complexes and isolated flavoproteins indicates that the main rate limitation for catalytic turnover is the proton abstraction from the substrate. The low solvent isotope effect (∼1.2) suggests efficient proton exchange with the bulk solvent likely with minimal sites involved. Overall the kinetic isotope and pH analytic data suggest that the free flavoprotein subunits and the intact membrane-bound complexes behave similarly in these reactions.

Table 4.

Substrate and solvent kinetic isotope effects in the succinate dehydrogenase reaction

In pL, L indicates H or D. SQR and QFR isotope effects were determined in the succinate–ferricyanide assay (23). Isolated E. coli SdhA and FrdA isotope effects were determined by monitoring direct reduction of FAD by substrate.

| Substrate isotope effect (ksucc-H4/ksucc-D4) |

Solvent isotope effect (kH/kD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pL7.0 | pL8.0 | pL7.0 | pL8.0 | |

| SQR | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| QFR | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| SdhA | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| FrdA | 5.0 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

Redox properties of the flavin

We also investigated other properties associated with the flavin of SdhA and FrdA testing the possibility that altered redox properties of FAD, such as changes in the Em in the unassembled flavoproteins that might lead to the reduced catalysis. As seen in Fig. 3 (A and B), spectroscopic titration of the FAD reduction potential using the dye indigotetrasulfonate yield an Em,7FAD in the range of −51 to −55 mV. This is in good agreement with the potential of the FAD found by protein film voltammetry for the soluble E. coli FrdAB (−50 mV) form (34) or by electron paramagnetic spectroscopy in the mammalian or bacterial SQR complex (−79 to −100 mV, respectively) (39, 40). The FAD reduction achieved with succinate (Fig. 2A), however, may indicate that the flavin potential is influenced by substrate binding. Indeed analysis of the Em,7FAD by equilibrium with the fumarate/succinate couple (Fig. 3C) showed that both FrdA and SdhA had the redox potential raised in the presence of the dicarboxylates to ∼0 mV. This effect of succinate/fumarate binding raises the redox potential of the FAD by ∼50 mV, an observation that is consistent with previous reports for mammalian SQR (39, 41).

Figure 3.

Determination of EmFAD in SdhA and FrdA. A and B, anaerobic determination of the reduction potentials was performed by equilibrium with indigotetrasulfornate as described under “Experimental procedures.” FrdA (A, 9.8 μm) and SdhA (B, 15 μm) were incubated with indigotetrasulfonate in the presence of xanthine oxidase and benzyl viologen. The arrows indicate the direction of the absorbance changes at 485 nm for FAD and 614 nm for indigotetrasulfonate. The insets show the corresponding Nernst plots. C, determination of the FrdA and SdhA flavin redox potential by equilibrium with succinate/fumarate (pH 7.0, 25 °C). The protein concentration for both FrdA and SdhA was 4.5 μm. The proteins were equilibrated with different ratios of succinate/fumarate as described under “Experimental procedures.” FrdA (open circles) and SdhA (closed circles). D, table summarizing the reduction potentials from A–C.

Discussion

Complex II is an essential component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and citric acid cycle. In humans a number of diseases are associated with dysfunction of complex II (7, 8, 13–18, 42). The majority of the complex II defects associated with disease are associated with mutations in the SDHB and SDHD genes (8). Mutations in these genes can lead to a situation where the SDHA flavoprotein subunit can remain free in the mitochondrial matrix (9, 11, 12). It has been postulated that this free SDHA flavoprotein might have off-pathway reactions such as ROS formation (12) that could contribute to the disease phenotype. In this communication we characterized the catalytic activity of the free flavoprotein subunit of complex II from both bacterial and mammalian sources. This information is useful to determine whether diseases associated with altered assembly of complex II might result from excess ROS produced by matrix localized SDHA or whether other metabolic deficiencies caused by a loss of complex II catalytic activity are the likely cause.

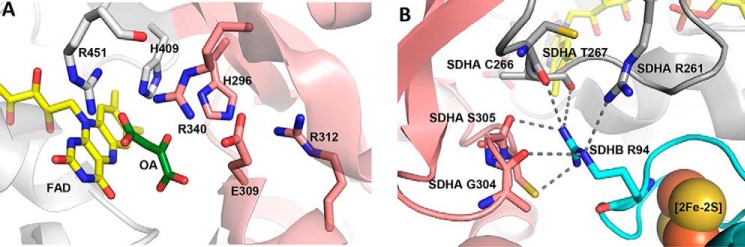

The flavoprotein of complex II is comprised of two structural domains consisting of a flavin-binding domain and a capping domain (3–5, 43, 44). Movement of the capping domain relative to the flavin domain is involved in orienting dicarboxylate substrates near the isoalloxazine ring of the FAD to allow succinate/fumarate interconversion. The catalytic mechanism for the complex II family of proteins is well established (28, 43) and involves two key steps. One step is hydride transfer between the substrate and flavin N5. The other step is a proton transfer between a conserved catalytic arginine (E. coli FrdAR287, SdhAR288, and hSDHAR340) and the substrate (Fig. 4A). Whether these reactions occur in a concerted or stepwise manner is not clear; however, both of these steps require precise alignment of substrate along the isoalloxazine ring of the FAD (28, 45, 46) and close proximity to the catalytic arginine. In addition, the associated reaction of proton delivery to the catalytic arginine and protonation/deprotonation of N5 coupled with FAD reduction/oxidation may also be critical and influence the overall turnover.

Figure 4.

X-ray structure of porcine complex II highlighting areas of interest. A, porcine SDHA (Protein Data Bank code 3SFD) near the dicarboxylate binding site. The FAD is shown as yellow sticks, the flavin-binding domain is shown in gray, and the capping-domain is shown in pink. Residues known to be involved in catalytic activity are shown as sticks. Oxaloacetate (OA) is shown in green. B, interaction of SDHB with SDHA. The [2Fe-2S] cluster from SDHB is shown as spheres. SDHB is shown in cyan, the SDHA capping-domain is shown in pink, and the flavin-binding domain is shown in gray. Hydrogen bonds from the conserved SDHBR56 linking to residues in the SDHA capping and flavin-binding domains are indicated by the dashed lines.

The data in Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 2 show that the catalytic properties of the human and bacterial flavoprotein subunits are remarkably similar. All have decreases in their catalytic rate of succinate oxidation and fumarate reduction of 2–3 orders of magnitude when compared with either the two subunit SdhAB subcomplex or the intact four subunit complex II. Moreover, these isolated flavoprotein subunits have minimal ROS production.

Although the dramatic decrease in activity initially seems surprising, it is comparable to what is observed in naturally occurring single-subunit complex II flavoprotein homologs. For example, the l-aspartate oxidase (LASPO) from E. coli (47, 48) is a particularly well characterized single subunit flavoprotein homolog of FrdA/SdhA with 100% conservation of all critical residues needed for complex II catalysis. The mechanism for coupling FAD reoxidation to fumarate reduction is therefore suggested to be similar to fumarate reduction by complex II enzymes (28, 48). However, there are also differences: LASPO contains only a low-potential noncovalent FAD (48) as its single redox cofactor, and it catalyzes oxidation of l-aspartate to imino-aspartate (49). The l-aspartate-fumarate reductase activity using BV+ is reported in the range of ∼0.3 s−1 (pH 8, 25 °C) (49), which is similar to the low activity described here for SdhA/FrdA. Thus, the low activity we find for the free SdhA/FrdA subunits as compared with complex II is consistent with that found for the native LASPO.

The mechanistic basis for this dramatic decrease in catalysis is somewhat difficult to understand. One possibility is that the flavoprotein is not fully folded in the absence of the other complex II subunits. Our data indicate that this scenario is unlikely. First, the active site appears to be intact because the flavoprotein is able to incorporate its covalent FAD cofactor. Moreover, the finding that the redox potential of the FAD is unaffected in the free flavoprotein subunits (Fig. 3) indicates that the protein environment immediately adjacent to the flavin is preserved. Further, these isolated flavoproteins can bind to dicarboxylates with reasonable affinity (26) (Fig. 1, B and C). The substrates are also likely to be oriented correctly, as assessed by the robust appearance of a charge transfer complex upon addition of oxaloacetate (26). As shown in previous binding studies using intact complex II (4, 26, 50), the charge transfer band reflects that the dicarboxylate aligns along the FAD N5, which causes orbital overlap between the flavin and substrate. A second possibility involves the misalignment of key catalytic residues and takes into consideration that the flavoprotein is a multidomain subunit with the active site located at the domain interface (Fig. 4A) between the flavin-binding and the capping domain. The flavin-binding domain contains the covalently bound FAD cofactor and the majority of the substrate-binding residues. In contrast, the capping domain contains important catalytic sides chains, including residues that stabilize the transition state and shuttle protons during oxidoreduction. Prior X-ray structures of complex II homologs identified that the flavin-binding and capping domains can adopt different interdomain angles (4, 43, 51–54), which may be influenced by the identity of the ligand bound to the active site (Fig. 4A) (55). From this a model for catalysis was developed where interdomain movement aligns key residues for catalysis (28, 38). If this mechanism is correct, even if the individual domains of the flavoprotein are correctly folded, catalysis could be inhibited if the capping domain does not close as efficiently or if it closes in a way where the catalytic residues are even subtly misaligned (38). This could impact one (or both) of two key catalytic properties: (i) proton shuttling or (ii) transition state formation. We first considered the proton shuttle. The proton delivery pathway is absolutely conserved in complex II proteins and homologs (28, 38), and mutagenesis of residues within this proton shuttling pathway suggests that its proper function is important for high rates of succinate oxidation. Because solvent and kinetic isotope effects show that proton transfer is rate-limiting in both succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate reductase reactions of these proteins (36–38), any reduction in proton transfer efficiency would be anticipated to directly impact the overall reaction rate. However, we did not detect significant changes in the substrate and solvent kinetic isotope effects of FrdA and SdhA compared with fully assembled complexes (Table 4). This suggests that the proton delivery pathway in the free flavoproteins is not impaired compared with the intact complexes. It may be that a more likely step to be affected is alteration of the properties of the catalytic arginine (38). In the absence of the iron–sulfur subunit the catalytic arginine is likely more exposed to solvent, which would be expected to increase its pKa (56) and make it a poor proton donor/acceptor. Even small differences in the active site architecture might influence the proton transfer between the conserved arginine thought to be the donor/acceptor during fumarate reduction or succinate oxidation, respectively (38). This proposal is also consistent with prior studies in NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase (57) and dihydrofolate reductase, where a combination of structural and computational analyses have shown that subtle changes at the active site, as well as conformational movements of a protein, can profoundly influence the rate of catalysis (58–60). The data presented here for the free flavoprotein subunit of complex II are consistent with changes in interdomain movement underlying the reduced catalysis of the isolated flavoproteins.

Why would the isolated flavoprotein subunits have a change in interdomain movement? Although there are no reported X-ray structures of the isolated complex II flavoprotein from any source, our recent analysis comparing the FrdA-SdhE complex to the FrdABCD complex indicates that the iron–sulfur protein partially acts as a regulatory subunit of the flavoprotein and stabilizes the interdomain orientation (26). This is entirely consistent with the recent observation for a similar binding interaction between E. coli SdhA-SdhE (61). One conclusion of this work was that in the absence of the iron–sulfur subunit, the two domains of the flavoprotein would be more freely flexible. Our kinetic work here would now suggest that this loss of interdomain guiding results in a less frequent sampling of an interdomain conformation that supports productive catalysis. A survey of the complex II homolog structures supports this conclusion. Indeed, it shows that an arginine residue conserved in all iron–sulfur subunits of complex II homologs (i.e. hSDHBR94 or FrdBR58) makes numerous hydrogen-bond contacts with the flavin-binding and capping domains of the flavoprotein subunit (Fig. 4B). It is notable that in the low activity single subunit E. coli LASPO, there is only one hydrogen-bond contact in the LASPO structure (47) in the same region where the iron–sulfur subunit of complex II stabilizes the interaction of the flavin-binding and capping domains (Fig. 4B). The iron–sulfur protein may also have an electronic interaction with the FAD in the flavoprotein via the proximal redox center [2Fe-2S] in the iron–sulfur subunit (40).

The data in Table 2 and previous studies on the binding of SdhE to E. coli FrdA/SdhA (26) are also consistent with the idea that the catalytic activity of the flavoprotein can be significantly modulated by binding to a partner protein. For example, succinate oxidation in the intact SQR complex occurs at a rate of 100 s−1 (Table 2), whereas when SdhA/hSDHA is associated with SdhE/SDHAF2, the rate is diminished to 0.001 s−1. This variation in rate of 5 orders of magnitude may reflect evolutionary constraints to inhibit unwanted side reactions that might occur prior to assembly in a mature complex. For example, LASPO and mitochondrial dihydroorotate dehydrogenase can reduce fumarate in addition to their normal substrates (48, 62). Therefore, it might be possible that the unassembled flavoproteins could gain these off-path reactions that intact complex II lacks. We did investigate whether SdhA, hSDHA, and FrdA, in their free form or in complex with SdhE or SDHAF2, could react with l-aspartate or dihydroorotate but found no detectable activity (data not shown). Thus, we did not find any evidence for moonlighting activity of the free flavoproteins. In addition to identifying a loss of activity in the isolated flavoproteins, one impact of this work is in the bacterial expression of the flavoproteins subunit of human complex II. One notable difference between the bacterial and mammalian proteins was in their response to their covalent FAD assembly factors. In bacteria, SdhE readily dissociates from either SdhA or FrdA once the covalent FAD linkage has formed (35, 63, 64). By contrast, SDHAF2 binds very tightly to hSDHA, and mild chaotropic agents were needed to dissociate the tightly bound complex. The reason for the very tight binding between hSDHA and SDHAF2 compared with E. coli SdhA/FrdA–SdhE is not known but is consistent with prior reports on the homologous complex from yeast, SdhA–Sdh5. Bacterial SdhE and yeast Sdh5 have identical structural cores (65, 66) with this conserved region thought to be sufficient for enhancing covalent flavinylation. Here we confirm that bacterial SdhE cannot enhance the covalent flavinylation of the hSDHA, yet prior studies revealed that yeast Sdh5 can complement mutations in hSDHAF2 (9). When the assembly of yeast complex II is perturbed, a complex between SdhA–Sdh5 was found in the mitochondrial matrix (9). This is consistent with the tighter association we also find for the mammalian proteins. Compared with E. coli SdhE, the mature human SDHAF2 and yeast Sdh5 are ∼50% larger. For example, the human SDHAF2 is extended by 31 amino acids at its N terminus and 16 amino acids at its C terminus compared with the shorter bacterial SdhE (88 amino acids total). Whether these N- and C-terminal extensions contribute to the tighter binding of the human SDHA–SDHAF2 complex or assist with covalent flavinylation has not yet been determined. This tight association may be needed to protect hSDHA and SDHAF2 from LON-mediated proteolysis (67).

In, conclusion the findings are as follows: (i) mammalian and bacterial complex II flavoproteins are catalytically highly similar; (ii) the free flavoprotein subunits of complex II have low inherent catalytic activity and thus are not likely by themselves to be an important source of ROS; and (iii) the lower activity of the free flavoprotein subunit compared with the intact complex likely reflects the absence of a partner protein (i.e. the iron–sulfur subunit) whose binding is expected to align active site residues to enable more robust catalytic activity.

Experimental procedures

Strains, plasmids, and protein expression

The E. coli strains and the plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. To express the mature forms of human SDHA and SDHAF2 lacking the N-terminal mitochondrial transit peptide their respective DNA sequences were optimized for expression in E. coli and synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ). The synthesized DNA was then cloned into the 5′ BamHI and 3′ SalI site of pQE-80L (Qiagen). The resulting constructs have a N-terminal His6 tag under the control of an isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible T5 promoter. The resulting N terminus of the recombinant human SDHA flavoprotein including the His tag was MRGSHHHHHHG-43SAKVSDSISA.

Construction of pQE-hSDHA/SDHAF2. hSDHA and human SDHAF2 were expressed from a single polycistronic transcript that includes an N-terminal His6-hSdhA construct under control of a T5 promoter and untagged mature hSDHAF2 that retains the Shine–Delgarno translational enhancer elements from the original T5 promoter region found in plasmid pQE80L. First, pQN-hSDHAF2 was created noting that the sequence of mature hSDHAF2 starts at amino acid 37 (67). Our construct was cloned into the BglII–SalI site of the pQT vector (pQN-hSDHAF2), and the first two residues are replaced with Met and Arg; thus in our construct SDHAF2 starts with Ser-39. Thus, the N terminus of SDHAF2, which lacks the His tag, was MR-39SPTDSQKDMI. The SDHAF2 N terminus was designed from the work of Bezawork-Galeta et al. (67), in which it was shown that there is a two-step processing of the SDHAF2 transit peptide.

To make pQE-hSDHA/hSDHAF2, the AatII–Ecl136II fragment of pQE-hSDHA harboring the T5-hSDHA was cloned into the AatII–PsiI site of vector pQN-hSDHAF2. The latter digestion removes the initial portion of the T5 promoter for SDHAF2 so that expression of both genes is from a single T5 promoter. Plasmid pFrdA used to express the tag-free WT E. coli FrdA flavoprotein subunit was constructed as previously described (35).

DNA manipulations were performed using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) with appropriate primers obtained from Eurofins MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). All mutations and constructs were verified by DNA sequencing (Sequetech, Mountain View, CA).

The E. coli SdhA and FrdA subunits containing an N-terminal His6 tag were expressed and purified as previously described (35). The hSDHA was expressed from plasmid pQE-hSDHA/SDHAF2. E. coli BL21Gold(DE3) cells transformed with pQE-hSDHA/SDHAF2 and the chaperone containing plasmid pKJE7 were maintained in the presence of 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 20 μg/ml of chloramphenicol throughout cell growth. A 5-ml starter culture was grown overnight in 1 ml of LB-broth containing the antibiotics at 37 °C with moderate aeration. The following morning 50 ml of LB medium was inoculated with 1 ml of the overnight culture and growth continued for 5 h at 30 °C. The entire culture was then used to inoculate 1 liter of LB media in a 4-liter flask, and growth was initiated at 25 °C with moderate aeration. After 1 h the cells were induced with 0.1 mm IPTG and grown for 17 h. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g for 10 min), and the cell pellet was washed one time with 5 mm MgCl2 and then stored at −80 °C.

Protein purification

His-tagged proteins were purified on Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen). Frozen cells were resuspended in 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, with Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablets (Roche Applied Sciences). The cells were disrupted with a EmulsiFlex-C5 homogenizer (Avestin, Ottawa, Canada), and the cell lysate obtained by centrifugation (120,000 × g for 40 min). The lysate was applied to Ni-NTA gravity column. The column was washed with the equilibration buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 30 μm imidazole, 0.5 m NaCl, 10% glycerol), and the His-tagged flavoprotein was eluted with 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 250 mm imidazole, 0.1 m NaCl, 10% glycerol. The eluted fractions containing hSDHA were concentrated on a Centriprep 30-kDa (Millipore) centrifugal filter. The concentrated protein was then diluted 10-fold with 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol and applied to diethylaminoethyl Sepharose fast flow resin equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, (pH 7.6) and eluted on an AKTA Explorer (GE Healthcare) with a 20–120 mm NaCl gradient in the same buffer. The eluted fractions containing hSDHA were concentrated as described above and stored at −80 °C. The E. coli FrdA/SdhA proteins were purified as described (35).

Guanidine HCl treatment

A 3 ml of Ni-NTA (Thermo Scientific) gravity column was equilibrated with 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 25% glycerol, 0.1 m NaCl at 4 °C. The purified hSDHA–SDHAF2 complex was bound to the column and washed with the same equilibration buffer used to purify the complex. 20 ml of 1 m guanidine HCl, in the same buffer, was used to wash the column over 40 min. Guanidine HCl was removed by decreasing the concentration (1.0–0 m) of guanidine HCl in the washing buffer; in 0.2 m step increments and 5 ml for each wash step. Finally the column was washed with the equilibration buffer and hSDHA eluted with 0.25 m imidazole in the buffer. After concentration with Centriprep 30-kDa filters and buffer exchange using the same equilibration buffer, the resulting Gu-hSDHA which was 85–95% free of SDHAF2 was stored at −80 °C.

Optical and kinetic studies

Spectral and kinetic assays were done using an Agilent 8453 UV-visible spectrophotometer. Kinetic studies were performed in 50 mm Bis-Tris-propane (BPT), 0.2 mm EDTA at 30 °C. FAD reduction was monitored at 460 nm after manual addition of succinate to the assay cuvette. The succinate dehydrogenase reaction (succinate–DCIP) was determined in the presence of 50 μm DCIP, (ϵ600 = 21.8 mm−1 cm−1) and various succinate concentrations. Superoxide production was monitored in the presence of 20 μm acetylated cytochrome c at 550 nm. Hydrogen peroxide formation was detected at 572 nm (resorufin formation, ϵ572 = 54 mm−1 cm−1) using 10 μm Amplex UltraRed (Invitrogen) and peroxidase as previously described (68). Catalase was added to quench the activity.

Fumarate reductase activity with benzyl viologen (BV)

The reaction was performed anaerobically as described (29) in 50 mm BTP, pH 7.0, at 30 °C. Glucose (10 mm) and glucose/oxidase were added to maintain anaerobic conditions. BV (0.2 mm) was substoichiometrically reduced with sodium dithionite to yield ∼90 μm BV+ (ϵ550 = 7.8 mm−1). Enzyme was added, and the reaction was started with 10 mm fumarate. For the membrane-bound SQR and QFR complexes, 0.05% Triton X-100 was included in the reaction mixture.

Kinetic isotope effects

The effect of solvent deuteration on turnover rates was followed at 30 °C. For the solvent kinetic isotope effect of the SQR and QFR complexes, the succinate-ferricyanide reductase assay was used as previously described (23). The solvent kinetic isotope effect for the isolated SdhA and FrdA was measured by the direct monitoring of flavin reduction as described above. Buffer and substrate solutions were prepared in both D2O (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA) and H2O, and corrections for pD = pH meter reading +0.4 were done as described (69). The substrate kinetic isotope effect using succinate deuterated at positions C2 and C3 (succinic-D4; Sigma–Aldrich) were done in H2O containing buffer with succinate-H4 or succinate-D4. The protein containing solutions were equilibrated for ∼1 min, and the reaction was started by the addition of either succinate-D4 or succinate-H4. The substrate and solvent isotope effects were calculated as a ratio (kH/kD). pL is defined as where L = H or D.

Determination of FAD reduction potential with indigotetrasulfonate

The reductive titration of SdhA and FrdA were performed spectroscopically according to the method of Massey (70) using the reference dye indigotetrasulfonate (Sigma) (Em.7 = −46 mV). The reaction was done in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, at 25 °C. Anerobic conditions were established in the presence of 10 mm glucose, glucose oxidase/catalase with argon layered upon the top of the cuvette. Indigotetrasulfonate was added to the cuvette to reach A614 = 0.15. Xanthine (0.3 mm) and 20 μm xanthine oxidase were also added to the cuvette. After the addition of the flavoproteins, the reaction was initiated by 20 μm benzyl viologen. The spectra were collected over a period of 40 min. The Em values were determined using the Nernst equation for n = 2 for FAD and the dye as described (71). The absorbance changes corresponding to the reduction of the dye (614 nm) were plotted against those of the flavin recorded at 485 nm, the isosbestic point for indigotetrasulfonate. Two independent titrations were performed.

FAD redox potential determination by equilibrium with succinate/fumarate

The redox potential (Em,7FAD) in the E. coli flavoproteins was titrated with the succinate/fumarate couple. The steady-state reduction levels of FAD at each succinate/fumarate ratio were determined by calculating the residual fraction of oxidized FAD (466–750 nm) and plotting against the redox potential poised by the succinate/fumarate couple (Em = +30 mV, n = 2) calculated by the Nernst equation. E. coli SdhA or FrdA, 4.5 μm, were equilibrated in 50 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) at 25 °C. 1 m succinate (pH 7.0) and 1 m fumarate (pH 7.0) were mixed in different ratios at 10 mm total final concentration for the redox titration. A spectrum was recorded when equilibrium had been reached (∼2 min). The fully reduced FAD spectrum was recorded after the addition of sodium dithionite. 100% oxidized FAD corresponded to the spectrum obtained in the presence of 10 mm fumarate. The graph (Fig. 3) represents simulation of the Nernst equation with Em = 0 mV. The potential measurements with the succinate/fumarate couple were repeated three times.

In-gel flavin detection

The protein sample was separated by SDS-PAGE using Bio-Rad Any kDa gels. Following separation, the gel was incubated in 10% acetic acid, 20% methanol for 5 min. FAD fluorescence was detected using a Safe Imager 2.0 blue-light transilluminator (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The ImageJ (National Institutes of Health) program was used for quantification of FAD levels and relative protein ratios.

Immunodetection of proteins

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad). Proteins containing a His6 tag were detected using murine monoclonal anti-His6 antibody (Aviva Systems Biology; catalog no. OAE00010) and horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher). The tag-free SDHAF2 protein was detected using a rabbit mAb (Cell Signaling; catalog no. 45849). A mAb against hSDHA (AbCam catalog no. ab14715) was also used to detect the mammalian protein.

Analytical methods

Protein concentration was determined by the BCA protein assay kit from Pierce. The concentration of the flavoproteins was determined in 0.5% SDS from the absorbance of the covalent FAD cofactor assuming 1 mol FAD (ϵ447 = 12 mm−1 cm−1) per mol flavoprotein (72). Proteins in SDS-PAGE gels were stained with Coomassie Blue G (Sigma–Aldrich).

Author contributions

E. M., T. M. I., and G. C. conceptualization; E. M. and G. C. resources; E. M., S. R., and T. M. I. data curation; E. M. and G. C. formal analysis; E. M. and G. C. supervision; E. M., T. M. I., and G. C. funding acquisition; E. M., S. R., and T. M. I. investigation; E. M. and S. R. methodology; E. M., S. R., and G. C. writing-original draft; E. M. and G. C. project administration; E. M., T. M. I., and G. C. writing-review and editing.

Acknowledgment

We thank Izumi Yamakawa for help with analysis of the association of the complex of hSDHA–SDHAF2.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM61606 (to G. C. and T. M. I.) and Department of Veterans Affairs Grant BX001077 (to G. C.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- SQR

- succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase

- QFR

- quinol:fumarate oxidoreductase

- FrdA

- free flavoprotein subunit of E. coli QFR

- hSDHA

- free flavoprotein of human SQR/complex II

- hSDHAF2

- human SDHAF2 covalent flavin assembly factor

- BTP

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- DCIP

- 2,6-dichloroindophenol

- IPTG

- β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- LASPO

- l-aspartate oxidase

- Ni-NTA

- nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid

- BV

- benzyl viologen.

References

- 1. Hägerhäll C. (1997) Succinate:quinone oxidoreductases: variations on a conserved theme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1320, 107–141 10.1016/S0005-2728(97)00019-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cecchini G. (2003) Function and structure of complex II of the respiratory chain. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 77–109 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yankovskaya V., Horsefield R., Törnroth S., Luna-Chavez C., Miyoshi H., Léger C., Byrne B., Cecchini G., and Iwata S. (2003) Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science 299, 700–704 10.1126/science.1079605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang L. S., Shen J. T., Wang A. C., and Berry E. A. (2006) Crystallographic studies of the binding of ligands to the dicarboxylate site of complex II, and the identity of the ligand in the “oxaloacetate-inhibited” state. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757, 1073–1083 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun F., Huo X., Zhai Y., Wang A., Xu J., Su D., Bartlam M., and Rao Z. (2005) Crystal structure of mitochondrial respiratory membrane protein complex II. Cell 121, 1043–1057 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Iverson T. M., Maklashina E., and Cecchini G. (2012) Structural basis for malfunction in complex II. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 35430–35438 10.1074/jbc.R112.408419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bezawork-Geleta A., Rohlena J., Dong L., Pacak K., and Neuzil J. (2017) Mitochondrial complex II: At the crossroads. Trends Biochem. Sci. 42, 312–325 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bardella C., Pollard P. J., and Tomlinson I. (2011) SDH mutations in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1807, 1432–1443 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hao H. X., Khalimonchuk O., Schraders M., Dephoure N., Bayley J. P., Kunst H., Devilee P., Cremers C. W., Schiffman J. D., Bentz B. G., Gygi S. P., Winge D. R., Kremer H., and Rutter J. (2009) SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science 325, 1139–1142 10.1126/science.1175689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Na U., Yu W., Cox J., Bricker D. K., Brockmann K., Rutter J., Thummel C. S., and Winge D. R. (2014) The LYR factors SDHAF1 and SDHAF3 mediate maturation of the iron–sulfur subunit of succinate dehydrogenase. Cell Metab. 20, 253–266 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Vranken J. G., Bricker D. K., Dephoure N., Gygi S. P., Cox J. E., Thummel C. S., and Rutter J. (2014) SDHAF4 promotes mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase activity and prevents neurodegeneration. Cell Metab. 20, 241–252 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van Vranken J. G., Na U., Winge D. R., and Rutter J. (2015) Protein-mediated assembly of succinate dehydrogenase and its cofactors. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 50, 168–180 10.3109/10409238.2014.990556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baysal B. E. (2002) Hereditary paraganglioma targets diverse paraganglia. J. Med. Genet. 39, 617–622 10.1136/jmg.39.9.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. King K. S., and Pacak K. (2014) Familial pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 386, 92–100 10.1016/j.mce.2013.07.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martucci V. L., and Pacak K. (2014) Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: diagnosis, genetics, management, and treatment. Curr. Probl. Cancer 38, 7–41 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gill A. J. (2012) Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and mitochondrial driven neoplasia. Pathology 44, 285–292 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283539932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yamamoto H., and Oda Y. (2015) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: recent advances in pathology and genetics. Pathol. Int. 65, 9–18 10.1111/pin.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ozluk Y., Taheri D., Matoso A., Sanli O., Berker N. K., Yakirevich E., Balasubramanian S., Ross J. S., Ali S. M., and Netto G. J. (2015) Renal carcinoma associated with a novel succinate dehydrogenase A mutation: a case report and review of literature of a rare subtype of renal carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 46, 1951–1955 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Imlay J. A. (1995) A metabolic enzyme that rapidly produces superoxide, fumarate reductase of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19767–19777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Messner K. R., and Imlay J. A. (2002) Mechanism of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide formation by fumarate reductase, succinate dehydrogenase, and aspartate oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42563–42571 10.1074/jbc.M204958200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Quinlan C. L., Orr A. L., Perevoshchikova I. V., Treberg J. R., Ackrell B. A., and Brand M. D. (2012) Mitochondrial complex II can generate reactive oxygen species at high rates in both the forward and reverse reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 27255–27264 10.1074/jbc.M112.374629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ishii T., Yasuda K., Akatsuka A., Hino O., Hartman P. S., and Ishii N. (2005) A mutation in the SDHC gene of complex II increases oxidative stress, resulting in apoptosis and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 65, 203–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maklashina E., Iverson T. M., Sher Y., Kotlyar V., Andréll J., Mirza O., Hudson J. M., Armstrong F. A., Rothery R. A., Weiner J. H., and Cecchini G. (2006) Fumarate reductase and succinate oxidase activity of Escherichia coli complex II homologs are perturbed differently by mutation of the flavin binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11357–11365 10.1074/jbc.M512544200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cecchini G., Schröder I., Gunsalus R. P., and Maklashina E. (2002) Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1553, 140–157 10.1016/S0005-2728(01)00238-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zafreen L., Walker-Kopp N., Huang L. S., and Berry E. (2016) In-vitro, SDH5-dependent flavinylation of immobilized human respiratory complex II flavoprotein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 604, 47–56 10.1016/j.abb.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sharma P., Maklashina E., Cecchini G., and Iverson T. M. (2018) Crystal structure of an intermediate of the covalent flavinylation process of respiratory complex II. Nat. Commun. 9, 274 10.1038/s41467-017-02713-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Starbird C. A., Maklashina E., Sharma P., Qualls-Histed S., Cecchini G., and Iverson T. M. (2017) Structural and biochemical analyses reveal insights into covalent flavinylation of the Escherichia coli complex II homolog quinol:fumarate reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 12921–12933 10.1074/jbc.M117.795120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reid G. A., Miles C. S., Moysey R. K., Pankhurst K. L., and Chapman S. K. (2000) Catalysis in fumarate reductase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1459, 310–315 10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00166-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ackrell B. A., Armstrong F. A., Cochran B., Sucheta A., and Yu T. (1993) Classification of fumarate reductases and succinate dehydrogenases based upon their contrasting behaviour in the reduced benzylviologen/fumarate assay. FEBS Lett. 326, 92–94 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81768-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mowat C. G., Pankhurst K. L., Miles C. S., Leys D., Walkinshaw M. D., Reid G. A., and Chapman S. K. (2002) Engineering water to act as an active site acid catalyst in a soluble fumarate reductase. Biochemistry 41, 11990–11996 10.1021/bi0203177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ackrell B. A., Kearney E. B., and Edmondson D. (1975) Mechanism of the reductive activation of succinate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 250, 7114–7119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kotlyar A. B., and Vinogradov A. D. (1984) Interaction of the membrane-bound succinate dehydrogenase with substrate and competitive inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 784, 24–34 10.1016/0167-4838(84)90168-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ackrell B. A., Cochran B., and Cecchini G. (1989) Interactions of oxaloacetate with Escherichia coli fumarate reductase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 268, 26–34 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90561-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Léger C., Heffron K., Pershad H. R., Maklashina E., Luna-Chavez C., Cecchini G., Ackrell B. A., and Armstrong F. A. (2001) Enzyme electrokinetics: energetics of succinate oxidation by fumarate reductase and succinate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 40, 11234–11245 10.1021/bi010889b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Maklashina E., Rajagukguk S., Starbird C. A., McDonald W. H., Koganitsky A., Eisenbach M., Iverson T. M., and Cecchini G. (2016) Binding of the covalent flavin assembly factor to the flavoprotein subunit of complex II. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 2904–2916 10.1074/jbc.M115.690396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hirst J., Ackrell B. A. C., and Armstrong F. A. (1997) Global observation of hydrogen/deuterium isotope effects on bidirectional catalytic electron transport in an enzyme: direct measurement by protein film voltammetry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 7434–7439 10.1021/ja9631413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kaczorowski G. J., Cheung Y. F., and Walsh C. (1977) Substrate kinetic isotope effects in dehydrogenase coupled active transport in membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 16, 2619–2628 10.1021/bi00631a007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pankhurst K. L., Mowat C. G., Rothery E. L., Hudson J. M., Jones A. K., Miles C. S., Walkinshaw M. D., Armstrong F. A., Reid G. A., and Chapman S. K. (2006) A proton delivery pathway in the soluble fumarate reductase from Shewanella frigidimarina. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20589–20597 10.1074/jbc.M603077200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ohnishi T., King T. E., Salerno J. C., Blum H., Bowyer J. R., and Maida T. (1981) Thermodynamic and electron paramagnetic resonance characterization of flavin in succinate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 256, 5577–5582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng V. W., Piragasam R. S., Rothery R. A., Maklashina E., Cecchini G., and Weiner J. H. (2015) Redox state of flavin adenine dinucleotide drives substrate binding and product release in Escherichia coli succinate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry 54, 1043–1052 10.1021/bi501350j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bonomi F., Pagani S., Cerletti P., and Giori C. (1983) Modification of the thermodynamic properties of the electron-transferring groups in mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase upon binding of succinate. Eur. J. Biochem. 134, 439–445 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rutter J., Winge D. R., and Schiffman J. D. (2010) Succinate dehydrogenase: assembly, regulation and role in human disease. Mitochondrion 10, 393–401 10.1016/j.mito.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Iverson T. M., Luna-Chavez C., Schröder I., Cecchini G., and Rees D. C. (2000) Analyzing your complexes: structure of the quinol-fumarate reductase respiratory complex. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10, 448–455 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00113-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lancaster C. R., Kröger A., Auer M., and Michel H. (1999) Structure of fumarate reductase from Wolinella succinogenes at 2.2 A resolution. Nature 402, 377–385 10.1038/46483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leys D., Tsapin A. S., Nealson K. H., Meyer T. E., Cusanovich M. A., and Van Beeumen J. J. (1999) Structure and mechanism of the flavocytochrome c fumarate reductase of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1113–1117 10.1038/70051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mowat C. G., Moysey R., Miles C. S., Leys D., Doherty M. K., Taylor P., Walkinshaw M. D., Reid G. A., and Chapman S. K. (2001) Kinetic and crystallographic analysis of the key active site acid/base arginine in a soluble fumarate reductase. Biochemistry 40, 12292–12298 10.1021/bi011360h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mattevi A., Tedeschi G., Bacchella L., Coda A., Negri A., and Ronchi S. (1999) Structure of l-aspartate oxidase: implications for the succinate dehydrogenase/fumarate reductase oxidoreductase family. Structure 7, 745–756 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80099-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tedeschi G., Ronchi S., Simonic T., Treu C., Mattevi A., and Negri A. (2001) Probing the active site of l-aspartate oxidase by site-directed mutagenesis: role of basic residues in fumarate reduction. Biochemistry 40, 4738–4744 10.1021/bi002406u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tedeschi G., Nonnis S., Strumbo B., Cruciani G., Carosati E., and Negri A. (2010) On the catalytic role of the active site residue E121 of E. coli l-aspartate oxidase. Biochimie 92, 1335–1342 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dervartanian D. V., and Veeger C. (1964) Studies on succinate dehydrogenase: I. spectral properties of the purified enzyme and formation of enzyme–competitive inhibitor complexes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 92, 233–247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Huang L. S., Sun G., Cobessi D., Wang A. C., Shen J. T., Tung E. Y., Anderson V. E., and Berry E. A. (2006) 3-nitropropionic acid is a suicide inhibitor of mitochondrial respiration that, upon oxidation by complex II, forms a covalent adduct with a catalytic base arginine in the active site of the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5965–5972 10.1074/jbc.M511270200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tomasiak T. M., Maklashina E., Cecchini G., and Iverson T. M. (2008) A threonine on the active site loop controls transition state formation in Escherichia coli respiratory complex II. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15460–15468 10.1074/jbc.M801372200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bamford V., Dobbin P. S., Richardson D. J., and Hemmings A. M. (1999) Open conformation of a flavocytochrome c3 fumarate reductase. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 1104–1107 10.1038/70039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Iverson T. M., Luna-Chavez C., Cecchini G., and Rees D. C. (1999) Structure of the Escherichia coli fumarate reductase respiratory complex. Science 284, 1961–1966 10.1126/science.284.5422.1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Starbird C. A., Tomasiak T. M., Singh P. K., Yankovskaya V., Maklashina E., Eisenbach M., Cecchini G., and Iverson T. M. (2018) New crystal forms of the integral membrane Escherichia coli quinol:fumarate reductase suggest that ligands control domain movement. J. Struct. Biol. 202, 100–104 10.1016/j.jsb.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harms M. J., Schlessman J. L., Sue G. R., and García-Moreno B. (2011) Arginine residues at internal positions in a protein are always charged. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 18954–18959 10.1073/pnas.1104808108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shen A. L., Sem D. S., and Kasper C. B. (1999) Mechanistic studies on the reductive half-reaction of NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 5391–5398 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boehr D. D., Dyson H. J., and Wright P. E. (2008) Conformational relaxation following hydride transfer plays a limiting role in dihydrofolate reductase catalysis. Biochemistry 47, 9227–9233 10.1021/bi801102e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Arora K., and Brooks C. L. 3rd (2013) Multiple intermediates, diverse conformations, and cooperative conformational changes underlie the catalytic hydride transfer reaction of dihydrofolate reductase. Top. Curr. Chem. 337, 165–187 10.1007/128_2012_408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hanoian P., Liu C. T., Hammes-Schiffer S., and Benkovic S. (2015) Perspectives on electrostatics and conformational motions in enzyme catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 482–489 10.1021/ar500390e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Maher M. J., Herath A. S., Udagedara S. R., Dougan D. A., and Truscott K. N. (2018) Crystal structure of bacterial succinate:quinone oxidoreductase flavoprotein SdhA in complex with its assembly factor SdhE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 2982–2987 10.1073/pnas.1800195115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Inaoka D. K., Sakamoto K., Shimizu H., Shiba T., Kurisu G., Nara T., Aoki T., Kita K., and Harada S. (2008) Structures of Trypanosoma cruzi dihydroorotate dehydrogenase complexed with substrates and products: atomic resolution insights into mechanisms of dihydroorotate oxidation and fumarate reduction. Biochemistry 47, 10881–10891 10.1021/bi800413r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. McNeil M. B., Clulow J. S., Wilf N. M., Salmond G. P., and Fineran P. C. (2012) SdhE is a conserved protein required for flavinylation of succinate dehydrogenase in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 18418–18428 10.1074/jbc.M111.293803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. McNeil M. B., Hampton H. G., Hards K. J., Watson B. N., Cook G. M., and Fineran P. C. (2014) The succinate dehydrogenase assembly factor, SdhE, is required for the flavinylation and activation of fumarate reductase in bacteria. FEBS Lett. 588, 414–421 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Eletsky A., Jeong M. Y., Kim H., Lee H. W., Xiao R., Pagliarini D. J., Prestegard J. H., Winge D. R., Montelione G. T., and Szyperski T. (2012) Solution NMR structure of yeast succinate dehydrogenase flavinylation factor Sdh5 reveals a putative Sdh1 binding site. Biochemistry 51, 8475–8477 10.1021/bi301171u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lim K., Doseeva V., Demirkan E. S., Pullalarevu S., Krajewski W., Galkin A., Howard A., and Herzberg O. (2005) Crystal structure of the YgfY from Escherichia coli, a protein that may be involved in transcriptional regulation. Proteins 58, 759–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bezawork-Geleta A., Saiyed T., Dougan D. A., and Truscott K. N. (2014) Mitochondrial matrix proteostasis is linked to hereditary paraganglioma: LON-mediated turnover of the human flavinylation factor SDH5 is regulated by its interaction with SDHA. FASEB J. 28, 1794–1804 10.1096/fj.13-242420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kareyeva A. V., Grivennikova V. G., Cecchini G., and Vinogradov A. D. (2011) Molecular identification of the enzyme responsible for the mitochondrial NADH-supported ammonium-dependent hydrogen peroxide production. FEBS Lett. 585, 385–389 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rothery E. L., Mowat C. G., Miles C. S., Walkinshaw M. D., Reid G. A., and Chapman S. K. (2003) Histidine 61: an important heme ligand in the soluble fumarate reductase from Shewanella frigidimarina. Biochemistry 42, 13160–13169 10.1021/bi030159z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Massey V. (1991) A simple method for the determination of redox potentials. In Flavins and Flavoproteins, pp. 59–66, Walter de Gruyter, New York [Google Scholar]

- 71. Efimov I., Parkin G., Millett E. S., Glenday J., Chan C. K., Weedon H., Randhawa H., Basran J., and Raven E. L. (2014) A simple method for the determination of reduction potentials in heme proteins. FEBS Lett. 588, 701–704 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Cecchini G., Ackrell B. A., Deshler J. O., and Gunsalus R. P. (1986) Reconstitution of quinone reduction and characterization of Escherichia coli fumarate reductase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 1808–1814 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kitagawa M., Ara T., Arifuzzaman M., Ioka-Nakamichi T., Inamoto E., Toyonaga H., and Mori H. (2005) Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res 12, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Grivennikova V. G., Gavrikova E. V., Timoshin A. A., and Vinogradov A. D. (1993) Fumarate reductase activity of bovine heart succinate-ubiquinone reductase: new assay system and overall properties of the reaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1140, 282–292 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90067-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]