Abstract

The Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola (STRIVE), a phase 2/3 trial of an investigational Ebola vaccine, was implemented in April 2015 in Sierra Leone. Healthcare and Ebola frontline workers were randomized to immediate (within 7 days) or deferred (18–24 weeks) vaccination and observed from enrollment to 6 months postvaccination for safety and Ebola virus disease. There were concerns that high retention and compliance would be difficult to achieve, particularly for the deferred group. Trial staff conducted monthly calls to participants and home visits if needed. Retention was defined as completion of the final assessment at 6 months postenrollment and postvaccination. Full compliance was defined as completion of all monthly assessments before and 6 months after vaccination and vaccination per protocol. Logistic regression was used to identify demographic characteristics associated with these outcomes. Of 8626 participants enrolled, 7979 (92.5%) were retained postenrollment (95.2% in immediate vaccination arm, 89.8% in deferred arm). Overall, 68.8% were fully compliant postenrollment (73.4% in immediate arm, 64.2% in deferred arm). Among 7979 vaccinated participants, 95.9% were retained 6 months postvaccination, with no significant difference between study arms. Frontline workers and younger participants were least likely to be retained and had a lower likelihood of full compliance.

High retention of participants in a vaccine clinical trial in a low-resource setting, even among those assigned to deferred vaccination, was achievable. Younger participants and frontline workers may require additional follow-up strategies and resources.

Clinical Trials Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov [NCT02378753] and Pan African Clinical Trials Registry [PACTR201502001037220].

Keywords: Ebola, Ebola vaccine, retention, losses to follow-up, randomized clinical trial

In randomized clinical trials, poor participant retention can introduce bias and reduce study power, affecting the generalizability, validity, and reliability of results [1]. Factors associated with retention can include the following: study complexity; stigma associated with the disease being studied; not wanting to disclose trial participation; cost to participate, such as transportation costs and time off from work; health of participants; educational level; and occupation [2]. The Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola (STRIVE) is a phase 2/3 unblinded, randomized trial of an investigational Ebola vaccine, rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (Merck), to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the vaccine and was conducted in Sierra Leone. The study enrolled more than 8000 healthcare and frontline Ebola workers as study participants [3, 4]. Conducting a clinical trial in Sierra Leone during an Ebola outbreak posed challenges to participant follow-up. First, there was a lack of clinical trial experience and research infrastructure in Sierra Leone. Second, available resources focused on immediate outbreak response, and it was critical that those resources not be diverted for the sake of the trial. Third, STRIVE trial participants were healthcare and frontline Ebola response workers who worked long hours and provided essential clinical or response-related services at the height of the outbreak, and many were displaced due to job loss when the outbreak was waning. In this paper, we describe the methods used to reduce losses to follow-up and examine factors associated with retention and compliance with the study protocol. This trial was registered under ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02378753) and Pan African Clinical Trials Registry (PACTR201502001037220).

METHODS

Description of Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola

Participants were enrolled at 7 STRIVE trial sites in 5 districts highly affected by Ebola virus disease (Western Area Urban [Freetown], Western Area Rural, Bombali, Tonkolili, and 3 sites in Port Loko) from April 9 through August 15, 2015 [5]. To be eligible for the trial, participants had to be at least 18 years of age and be actively working as a healthcare provider (in a clinical or nonclinical role) or frontline Ebola worker (eg, contact tracer, ambulance crew, burial team). Participants had to assert that they were planning to reside in Sierra Leone for 6 months after enrollment and agree to be contacted monthly by telephone. Detailed contact information was collected during enrollment, including the following: participant address with important nearby landmarks; participant personal cell phone number; and name and cell phone number of an alternative contact, typically a close relative or friend who would know how to reach the participant if investigators had difficulty reaching them on their study or personal telephone.

At enrollment, participants were individually randomized to immediate (<7 days) or deferred (18–24 weeks) vaccination. Starting at approximately 17 weeks after enrollment, participants in the deferred group were contacted to return to the trial site where they were rescreened for eligibility, and those still eligible were vaccinated. Once deferred participants were vaccinated, they were referred to as “crossover vaccinated.”

Community sensitization to build awareness and support for the trial was initiated 4 months before the trial’s launch, followed by targeted information sessions conducted at local healthcare facilities, specialized Ebola facilities, and District Ebola Response Centers (Ebola coordination centers) to recruit participants. Senior staff from the Ministry of Health and Sanitation and the College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences conducted approximately 50 stakeholder sensitization meetings with community and government leaders at the national, district, and local levels [6]. These activities forged important relationships that supported community outreach throughout the trial. Details of STRIVE trial procedures are described elsewhere [3, 5].

The protocol was approved by the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Institutional Review Board, the Pharmacy Board of Sierra Leone, and the US Food and Drug Administration. All participants gave written informed consent.

Participant Follow-Up

Participants were followed for 6 months postvaccination. Several strategies were used to maximize participant retention and to ensure that participants would be reachable (Table 1). Each participant who enrolled was given a new cell phone and a SIM card that provided free access to a “closed-user-group.” This allowed free calls for the study staff to contact participants each month and for participants to call the trial hotline. This hotline was available for 24 hours a day and 7 days a week throughout the trial for procedural questions and referral for medical issues.

Table 1.

STRIVE Trial Strategies to Promote Participant Retention

| Category | Description of Strategy | Considerations and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Equipment | Cell phone/SIM card provided at enrollment | • At time of study planning, unclear whether most adults would own a cell phone. |

| Communications | Closed-user-group | • Participant could make free calls to trial hotline and study staff to report changes in health and request medical triage. • Free calls facilitated contact between participants and staff between scheduled monthly calls. • Study staff could make free calls to participants’ study cell phone in addition to personal telephone (multiple contacts). |

| Community engagement | Discussions with community leadership Leadership at local healthcare and Ebola facilities kept informed throughout the trial |

• Ongoing community engagement to identify and address rumors. • Engagement of hospital leadership important for keeping participants engaged in study over time including returning for crossover vaccination. |

| Flexible appointments | Study staff worked in 2 shifts, which allowed calls and home visits to participants outside of working hours as needed | • Because participants were working at time of enrollment, they had to schedule appointments taking into account their work hours. |

| Multiple locator information | If participant could not be reached by telephone after 6 attempts, study staff attempted to reach them through relative telephone number or a home visit | • Multiple methods to track participants including study, personal and a relative's cell phone number, home address. |

| Staff training and feedback | Ongoing staff training to improve communication skills, confidentiality during home visits. Progress on percentage of persons due for follow-up reached discussed at weekly staff meetings | • Staff assigned to specific areas for tracking participants at home. Teams provided feedback on success of making all telephone calls; troubleshoot problems together. |

Abbreviations: STRIVE, Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola.

Monthly Calls

Each month trained study staff conducted a structured telephone interview with participants that included questions to identify new or ongoing health events, including Ebola virus disease and newly recognized pregnancy for women. Participants who reported a new or ongoing health issue were referred to the study nurse for medical care as needed. Two call attempts were made each day (morning and evening) for 3 days until the participant was contacted, with staff having discretion of continuing attempts for up to 7 days to maximize the chance of reaching participants. Home visits were conducted if the participant was not reachable by telephone after at least 6 attempts. At every call or visit, locator and contact information was verified and updated if necessary.

If the participant could not be contacted within 14 days after the targeted monthly assessment date, that month’s assessment was recorded as not completed. Study staff attempted to contact the participant for the subsequent monthly calls using the same procedures described above. For the final assessment call, 6 months postvaccination (or postenrollment if not vaccinated), contact was attempted for up to 28 days after the target date before terminating the participant from the trial.

Telephone calls and home visits were conducted by approximately 100 recent nursing and pharmacy school graduates who were based at the 3 follow-up coordination and data management centers (follow-up centers): Western Area Urban (for participants from Western Area Urban and Western Area Rural districts), Bombali (for participants from Bombali and Tonkolili districts), and Port Loko (for participants from the 3 sites in Port Loko District). After the main protocol training with all study staff, refresher training sessions were conducted at individual follow-up sites to cover protocol updates, interpersonal communication skills, and maintain confidentiality while tracking participants in their communities. Retention rates were regularly reviewed by the STRIVE Data Safety and Monitoring Board and presented at weekly staff meetings at the 3 participant follow-up centers, where staff discussed strategies for contacting hard-to-reach participants.

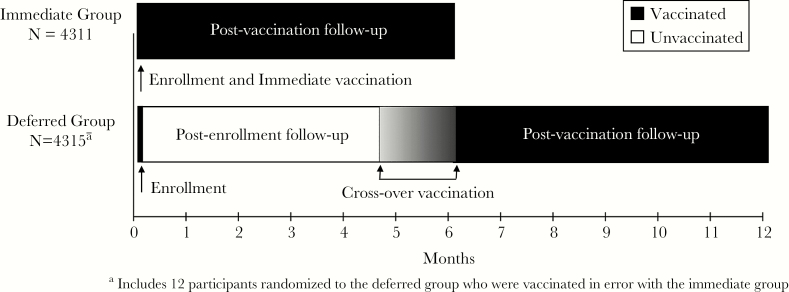

Duration of Follow-Up Participants in the immediate vaccination group were vaccinated within 7 days of enrollment and called monthly for 6 months postvaccination (Figure 1). Deferred vaccination group participants were observed from enrollment until they were vaccinated and then for 6 months postvaccination (Figure 1). Participants in both groups who were never vaccinated (eg, refused vaccination, or for the deferred group, ineligible at the time of vaccination) were observed for 6 months postenrollment.

Figure 1.

Postenrollment and postvaccination follow-up of the Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola (STRIVE) participants.

Data Analysis

Outcome: RetentionWe defined retention as completion of the final monthly assessment, and we measured it at 2 time points: postenrollment and postvaccination (Figure 1). For postenrollment retention, we compared results for the immediate and deferred groups, including those who were never vaccinated. For postvaccination retention, we compared vaccinated participants from the immediate group to vaccinated participants in the deferred group (ie, crossover participants). For the immediate vaccination group, the postenrollment and postvaccination time periods are the same, and the final assessment occurred 6 months after enrollment/vaccination. For the deferred vaccination group, the final postenrollment assessment occurred 18–24 weeks after enrollment (the assessment immediately before vaccination or at 6 months if not vaccinated), and the final postvaccination assessment occurred 6 months after crossover vaccination.

Outcome: Full Compliance

We also evaluated full compliance with the study protocol for postenrollment and postvaccination activities. Participants in the immediate vaccination group who were vaccinated within 7 days of enrollment and completed all 6 monthly follow-up interviews were defined as being in full compliance postenrollment and postvaccination. Deferred participants were considered in full compliance postenrollment if they were vaccinated per protocol (approximately 18–24 weeks after enrollment) and completed every monthly assessment from enrollment to vaccination. Deferred participants who were never vaccinated but completed every monthly interview through month 6 after enrollment were also considered fully compliant postenrollment. Full compliance postvaccination in crossover participants were those who were vaccinated per protocol and completed all 6 monthly interviews after vaccination (regardless of interview completion between enrollment and vaccination).

Statistical Methods

Participants were analyzed as randomized to either immediate or deferred groups. Participants who died during follow-up (n = 25) are excluded from these analyses of retention (although they are included in the reports of the trial results [3]).

We calculated the proportion of participants retained and in full compliance, and we identified factors associated with retention and full compliance using univariate and multivariate stepwise logistic regression models adjusted for randomization assignment (immediate vs deferred), age, sex, education, occupation, facility type, and enrollment site. Retention models also included vaccination status. The Western Area Rural site was selected as the referent group for site comparisons because it had the highest enrollment of the nonurban sites. A stepwise model selection approach was used to determine the best subset of predictors. The criterion used to enter the model was P = .10, with P = .01 as the criterion to stay in the model once additional predictors were added. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for each level of predictor compared with its reference groups.

RESULTS

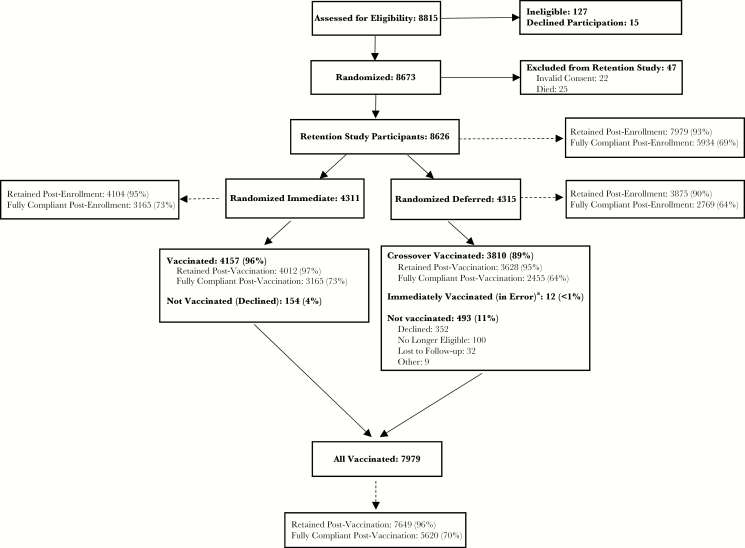

Of 8626 participants included in the analysis, 4311 were randomized to immediate vaccination and 4315 to deferred vaccination. Overall, 7979 (92.5%) of 8626 randomized participants were vaccinated; 4157 (96.4%) of the immediate participants were vaccinated, 3810 (88.9%) of the deferred participants were vaccinated during the crossover period, and 12 (<1%) of the deferred participants were vaccinated immediately in error (Figure 2). These last 12 participants were included in all retention and full compliance analyses as vaccinated and deferred randomization arm participants. For analyses of full compliance, they were considered noncompliant because they were not vaccinated per protocol.

Figure 2.

Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola (STRIVE) participant retention and compliance CONSORT diagram.

aIncluded in the vaccinated group; not eligible for crossover vaccination.

Most participants were male (60.6%) and the median age was 31 years (range, 18–79 years) (Table 2). The majority of participants were nurses (33.3%) or frontline workers (48.2%); 44.2% completed secondary school, and 41.6% had tertiary education. Education was related to occupation, with all (100%) doctors and a very high proportion of pharmacists (87%) and nurses (76%) having tertiary education. Frontline workers came from diverse educational backgrounds: the majority (59%) completed secondary school, whereas 25% had a primary school education or less. This diversity reflects the variety of technical roles frontline workers performed during the Ebola response, including contact tracing, ambulance driving, cleaning Ebola facilities, burial duties, and social mobilizing. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between immediate and deferred randomized groups.

Table 2.

Retention, Compliance, and Participant Characteristicsa by Randomization Arm and Vaccination Status: STRIVE (n = 8626)

| Study Variable | Immediate Vaccination (N = 4311) n (%) |

Deferred Vaccination (N = 4315) n (%) |

Crossoverb (N = 3810) n (%) |

All Vaccinated (N = 7979) n (%) |

All Randomized (N = 8626) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retained | 4104 (95.2) c | 3875 (89.8) | 3628 (95.2)d | 7649 (95.9)d | 7979 (92.5) |

| Fully Compliant | 3165 (73.4) | 2769 (64.2) | 2455 (64.4) | 5620 (70.4) | 5934 (68.8) |

| Male Gender | 2611 (60.6) | 2617 (60.6) | 2454 (64.4) | 5032 (63.1) | 5228 (60.6) |

| Age (Tertiled) (years) | |||||

| 18–27 | 1423 (33.0) | 1452 (33.7) | 1283 (33.7) | 2658 (33.3) | 2875 (33.3) |

| 28–35 | 1470 (34.1) | 1406 (32.6) | 1213 (31.8) | 2619 (32.8) | 2876 (33.3) |

| >35 | 1418 (32.9) | 1457 (33.8) | 1314 (34.5) | 2702 (33.9) | 2875 (33.3) |

| Primary Occupation | |||||

| Nursee | 1443 (33.5) | 1428 (33.1) | 988 (25.9) | 2336 (29.3) | 2871 (33.3) |

| Doctor | 13 (0.3) | 11 (0.3) | 7 (0.2) | 20 (0.3) | 24 (0.3) |

| Pharmacist | 20 (0.5) | 19 (0.4) | 19 (0.5) | 39 (0.5) | 39 (0.5) |

| Allied health professionalf | 77 (1.8) | 72 (1.7) | 58 (1.5) | 130 (1.6) | 149 (1.7) |

| Community health worker | 85 (2.0) | 93 (2.2) | 68 (1.8) | 153 (1.9) | 178 (2.1) |

| Laboratory worker | 133 (3.1) | 139 (3.2) | 139 (3.6) | 269 (3.4) | 272 (3.2) |

| Frontline workerg | 2065 (47.9) | 2089 (48.4) | 1340 (35.2) | 3377 (42.3) | 4154 (48.2) |

| Surveillance worker | 246 (5.7) | 250 (5.8) | 170 (4.5) | 410 (5.1) | 496 (5.8) |

| Other/Not reported | 229 (5.3) | 214 (5.0) | 128 (3.4) | 352 (4.4) | 443 (5.1) |

| Facility Type | |||||

| Clinic setting | 796 (18.5) | 794 (18.4) | 837 (22.0) | 1626 (20.4) | 1590 (18.4) |

| Ebola Facility | 1491 (34.6) | 1493 (34.6) | 686 (18.0) | 2119 (26.6) | 2984 (34.6) |

| Hospital | 1722 (39.9) | 1711 (39.7) | 1365 (35.8) | 3020 (37.8) | 3433 (39.8) |

| Other/Not reported | 302 (7.0) | 317 (7.3) | 922 (24.2) | 1214 (15.2) | 619 (7.2) |

| Education | |||||

| Tertiary | 1810 (42.0) | 1778 (41.2) | 1500 (39.4) | 3209 (40.2) | 3588 (41.6) |

| Secondary | 1874 (43.5) | 1937 (44.9) | 1773 (46.5) | 3614 (45.3) | 3811 (44.2) |

| Primary | 233 (5.4) | 216 (5.0) | 191 (5.0) | 420 (5.3) | 449 (5.2) |

| None | 374 (8.7) | 363 (8.4) | 338 (8.9) | 709 (8.9) | 737 (8.5) |

| Other/Not reported | 20 (0.5) | 21 (0.5) | 8 (0.2) | 27 (0.3) | 41 (0.5) |

| Enrollment Site District (Town) | |||||

| Western Area Rural | 941 (21.8) | 949 (22.0) | 849 (22.3) | 1746 (21.9) | 1890 (21.9) |

| Western Area Urban | 1624 (37.7) | 1620 (37.5) | 1370 (36.0) | 2915 (36.5) | 3244 (37.6) |

| Bombali | 599 (13.9) | 603 (14.0) | 544 (14.3) | 1137 (14.2) | 1202 (13.9) |

| Tonkolili | 366 (8.5) | 365 (8.5) | 338 (8.9) | 703 (8.8) | 731 (8.5) |

| Port Loko (Port Loko Town) | 433 (10.0) | 429 (9.9) | 398 (10.4) | 823 (10.3) | 862 (10.0) |

| Port Loko (Lunsar) | 197 (4.6) | 199 (4.6) | 172 (4.5) | 365 (4.6) | 396 (4.6) |

| Port Loko (Kaffu Bullom) | 151 (3.5) | 150 (3.5) | 139 (3.6) | 290 (3.6) | 301 (3.5) |

Abbreviation: STRIVE, Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola.

aThere were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the participants randomized to the immediate and deferred vaccination arms.

bParticipants randomized to deferred vaccination arm who were vaccinated 18–24 weeks after enrollment.

cParticipants randomized to immediate vaccination who were retained 6 months after enrollment.

dParticipants who were retained 6 months after vaccination.

eIncludes nurse, midwife, community health nurse, nursing aide, maternal-child health aide, nursing student, and vaccinator.

fIncludes dentist, medical counselor, nutritionist, and physiotherapist.

gIncludes contact tracers, ambulance crew, burial workers, cleaners, and swabber (persons taking postmortem skin/mucosal swabs for Ebola testing).

Retention and Full Compliance With Protocol

Overall, 7979 (92.5%) of the 8626 participants randomized were retained 6 months postenrollment: 95.2% of participants assigned to immediate vaccination and 89.8% of those assigned to deferred vaccination (Table 2). Almost all (95.9%) vaccinated participants were retained 6 months postvaccination: 96.5% of immediate vaccinated participants and 95.2% of crossover vaccinated participants. In the analysis of full protocol compliance, 5934 (68.8%) of the 8626 participants were in full compliance postenrollment: 73.4% of participants in the immediate vaccination group and 64.2% of those assigned to deferred vaccination. Of the vaccinated participants, 70.4% were in full compliance postvaccination: 73.4% of the immediate vaccinated and 64.4% of the crossover vaccinated participants.

Factors Associated With Retention

In multivariate analysis, 6-month postenrollment retention was higher among participants >27 years (adjusted OR [aOR] = 1.3, 95% CI, 1.1–1.6 for those 28–35; and aOR = 1.9, 95% CI, 1.6–2.4 for those >35) and those who were vaccinated (aOR: 3.5; 95% CI: 2.9–4.3) (Table 3). Significantly lower retention was associated with (1) frontline workers (aOR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.5–0.7) and surveillance workers (aOR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4–0.9) compared with nurses and (2) enrollment at the Port Loko Town site compared with the Western Area Rural site (aOR = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.7).

Table 3.

Factors Associated With Retention 6 Months Postenrollment Among Randomized Participants in the STRIVE Trial (n = 8626)

| Retained | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Factor-Level P Value |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Factor-Level P Value |

||

| Randomization Arm | Deferred Vaccination | 3875 (89.8) | ref | <.0001 | ||

| Immediate Vaccination | 4104 (95.2) | 2.3 (1.9–2.7) | ||||

| Vaccination Status | Unvaccinated | 3958 (88.8) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Vaccinated | 4021 (96.4) | 3.4 (2.8–4.1) | 3.5 (2.9–4.3) | |||

| Gender | Male | 4792 (91.7) | ref | .0003 | ||

| Female | 3187 (93.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) | ||||

| Age (tertiled) (years) | 18–27 | 2587 (90.0) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| 28–35 | 2668 (92.8) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | |||

| >35 | 2724 (94.7) | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 1.9 (1.6–2.4) | |||

| Occupation | Nursea | 2723 (94.8) | ref | <.0001 | ref | .0002 |

| Doctor | 22 (91.7) | 0.6 (0.1–2.6) | 0.5 (0.1–2.3) | |||

| Pharmacist | 37 (94.9) | 1.0 (0.2–4.2) | 0.9 (0.2–3.9) | |||

| Allied health professionalb | 143 (96.0) | 1.3 (0.6–3.0) | 1.2 (0.5–2.7) | |||

| Community health worker | 163 (91.6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | |||

| Laboratory worker | 260 (95.6) | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | |||

| Frontline workerc | 3777 (90.9) | 0.5 (0.5–0.7) | 0.6 (0.5–0.7) | |||

| Surveillance worker | 446 (89.9) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | |||

| Other/Not reported | 408 (92.1) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | |||

| Facility Type | Clinic setting | 1468 (92.3) | ref | .0276 | ||

| Ebola Facility | 2744 (92.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | ||||

| Hospital | 3207 (93.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | ||||

| Other/Not reported | 560 (90.5) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | ||||

| Enrollment Site | Western Area Rural | 1741 (92.1) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Western Area Urban | 3061 (94.4) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | |||

| Bombali | 1117 (92.9) | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | |||

| Tonkolili | 670 (91.7) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | |||

| Port Loko (Port Loko Town) | 747 (86.7) | 0.6 (0.4–0.7) | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | |||

| Port Loko (Lunsar) | 360 (90.9) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | |||

| Port Loko (Kaffu Bullom) | 283 (94.0) | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ref, reference category; STRIVE, Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola.

aIncludes nurse, midwife, community health nurse, nursing aide, maternal-child health aide, nursing student and vaccinator.

bIncludes dentist, medical counselor, nutritionist, and physiotherapist.

cIncludes contact tracers, ambulance crew, burial workers, cleaners, and swabbers (persons taking post mortem skin/mucosal swabs for Ebola testing).

Retention 6 months postvaccination was associated with older age (aOR = 1.5, 95% CI, 1.2–2.0 for those 28–35; and aOR = 2.2, 95% CI, 1.7–3.0 for those >35) and enrollment at sites in Bombali (aOR = 2.2; 95% CI, 1.3–3.6) and Tonkoli (aOR = 3.0; 95% CI, 1.5–6.3) Districts compared with Western Area Rural in adjusted analyses (Table 4). Among occupational groups, pharmacists had the highest retention (100%), nurses the second highest (99%), and doctors the lowest (90%). Compared with nurses, doctors (aOR = 0.1; 95% CI, 0.02–0.5), frontline workers (aOR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.2–0.4), community health workers (aOR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.1–0.8), and those no longer employed at the time of crossover vaccination (aOR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.2–0.4) had significantly lower retention.

Table 4.

Factors Associated With Postvaccination Retention Among Vaccinated Participants, STRIVE (n = 7979)

| Retained | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Factor-Level P Value |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Factor-Level P Value |

||

| Randomization Arm | Crossover Vaccination | 3628 (95.2) | ref | .0039 | ||

| Immediate Vaccination | 4012 (96.5) | 1.4 (1.1–1.7) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 4748 (94.6) | ref | <.0001 | ref | .0056 |

| Female | 2892 (98.1) | 3.0 (2.3–4.0) | 1.6 (1.2–2.3) | |||

| Age (tertiled) (years) | 18–27 | 2491 (93.8) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| >27–35 | 2539 (96.3) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | |||

| >35 | 2610 (97.6) | 2.6 (2.0–3.5) | 2.2 (1.7–3.0) | |||

| Occupation | Nursea | 2312 (99.0) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Doctor | 18 (90.0) | 0.1 (0.02–0.4) | 0.1 (0.02–0.5) | |||

| Pharmacist | 39 (100) | >99.9 (<0.01 to >99.9) | >99.9 (<0.01 to >99.9) | |||

| Allied health professionalb | 124 (95.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | 0.2 (0.1–0.5) | |||

| Community health worker | 145 (96.0) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | |||

| Laboratory worker | 261 (97.0) | 0.3 (0.1–0.7) | 0.5 (0.2–1.1) | |||

| Frontline workerc | 3176 (94.3) | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | 0.2 (0.2–0.4) | |||

| Surveillance worker | 393 (95.9) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | |||

| Not currently workingd | 836 (93.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.2) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | |||

| Other/Not reported | 336 (95.7) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) | |||

| Facility Type | Clinic setting | 1536 (94.6) | ref | .0002 | ||

| Ebola Facility | 2037 (96.2) | 1.4 (1.1–2.0) | ||||

| Hospital | 2921 (96.9) | 1.8 (1.3–2.4) | ||||

| Other/Not reported | 1146 (94.6) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | ||||

| Enrollment Site | Western Rural | 1655 (95.0) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Western Urban | 2783 (95.7) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | |||

| Bombali | 1117 (98.2) | 3.0 (1.8–4.9) | 2.2 (1.3–3.6) | |||

| Tonkolili | 695 (98.9) | 4.6 (2.2–9.6) | 3.0 (1.5–6.3) | |||

| Port Loko (Port Loko Town) | 768 (93.4) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | |||

| Port Loko (Lunsar) | 345 (94.4) | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 0.6 (0.3–1.0) | |||

| Port Loko (Kaffu Bullom) | 277 (95.5) | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ref, reference category; STRIVE, Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola.

aIncludes nurse, midwife, community health nurse, nursing aide, maternal-child health aide, nursing student, and vaccinator.

bIncludes pharmacist, dentist, medical counselor, nutritionist, and physiotherapist.

cIncludes contact tracers, ambulance crew, burial workers, cleaners, and swabbers (persons taking post mortem skin/mucosal swabs for Ebola testing).

dCurrent occupation information was updated for deferred crossover participants during the crossover period. Many were no longer working as the Ebola outbreak subsided, and Ebola response jobs ended. Crossover participants were offered vaccination regardless of work status.

Factors Associated With Full Protocol Compliance

Factors associated with full compliance postenrollment and postvaccination were similar. Randomization to immediate vaccination arm, age >27 years, sites in Bombali and Tonkoli Districts, and occupation as a laboratory worker were all associated with a higher likelihood of full protocol compliance during both postenrollment and postvaccination periods in multivariate analyses (Table 5). Bombali and Port Loko (Lunsar, Kaffu Bullom) District sites generally had higher rates of full compliance compared with Western Area Rural. Frontline and community health workers and those working at Ebola facilities had lower likelihood of completing all 6 assessments compared with nurses during both postenrollment and postvaccination follow-up.

Table 5.

Predictors of Full Compliance Among Randomized Participants Postenrollment and Postvaccination

| 6 Months Postenrollment (All Participants, n = 8626) | 6 Months Postvaccination (All Vaccinated, n = 7979) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliant | Univariable | Multivariable | Compliant | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||||

| N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Factor- Level P Value |

N (%) | Factor- Level P Value |

N (%) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Factor Level P Value |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Factor- Level P Value |

||

| Randomization Arm | Deferred Vaccination | 2769 (64.2) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 | 2455 (64.4) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Immediate Vaccination | 3165 (73.4) | 1.5 (1.4–1.7) | 1.6 (1.4–1.7) | 3165 (76.1) | 1.8 (1.6–1.9) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) | |||||

| Enrollment Site | Western Rural | 1189 (62.9) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 | 1118 (64.1) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Western Urban | 2176 (67.1) | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 2021 (69.5) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.1 (0.9–1.2) | |||||

| Bombali | 989 (82.3) | 2.7 (2.3–3.3) | 2.1 (1.8–2.6) | 861 (75.7) | 1.7 (1.5–2.1) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | |||||

| Tonkolili | 523 (71.5) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 595 (84.6) | 3.1 (2.5–3.9) | 2.6 (2.1–3.3) | |||||

| Port Loko (Port Loko) | 523 (60.7) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) | 508 (61.8) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | |||||

| Port Loko (Lunsar) | 296 (74.7) | 1.8 (1.4–2.2) | 1.4 (1.1–1.9) | 284 (78.0) | 2.0 (1.5–2.6) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | |||||

| Port Loko (Kaffu Bullom) | 238 (79.1) | 2.2 (1.7–3.0) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 233 (80.3) | 2.3 (1.7–3.1) | 2.0 (1.4–2.7) | |||||

| Age (tertiled) years | 18.0–27.5 | 1820 (63.3) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 | 1747 (65.8) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| 27.5–35.4 | 2017 (70.1) | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 1896 (71.9) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | |||||

| 35.4–79.5 | 2097 (72.9) | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) | 1977 (73.9) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 1.3 (1.2–1.5) | |||||

| Gender | Male | 3568 (68.2) | ref | .1761 | 3466 (69.0) | ref | .0001 | ||||

| Female | 2366 (69.6) | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 2154 (73.1) | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | |||||||

| Occupation | Nursea | 2071 (72.1) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 | 1769 (75.8) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Doctor | 19 (79.2) | 1.5 (0.6–3.9) | 1.3 (0.5–3.4) | 16 (80) | 1.3 (0.4–3.8) | 1.0 (0.3–3.0) | |||||

| Pharmacist | 25 (64.1) | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 25 (64.1) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | |||||

| Allied Health Professionalb | 101 (67.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 93 (71.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | |||||

| Community health worker | 110 (61.8) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 97 (64.2) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | |||||

| Laboratory worker | 218 (80.1) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 216 (80.3) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | |||||

| Frontline workerc | 2716 (65.4) | 0.7 (0.7–0.8) | 0.8 (0.8–0.9) | 2281 (67.7) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | |||||

| Surveillance worker | 361 (72.8) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 312 (76.1) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | |||||

| Other/Not reported | 313 (70.7) | 0.9 (0.8–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 256 (72.9) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | |||||

| Not currently workingd | NA | NA | NA | 555 (62.2) | 0.5 (0.5–0.6) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) | |||||

| Facility Type | Clinic setting | 1140 (71.7) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 | 1154 (71.1) | ref | <.0001 | ref | <.0001 |

| Ebola Facility | 1855 (62.2) | 0.7 (0.6–0.7) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 1393 (65.8) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | |||||

| Hospital | 2524 (73.5) | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 2279 (75.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | |||||

| Other/Not reported | 415 (67) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 794 (65.5) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) | |||||

| Vaccination Status | Unvaccinated | 2769 (62.1) | ref | <.0001 | |||||||

| Vaccinated | 3165 (75.9) | 1.9 (1.8–2.1) | |||||||||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ref, reference category; NA, not applicable.

aIncludes nurse, midwife, community health nurse, nursing aide, maternal-child health aide, nursing student, and vaccinator.

bIncludes pharmacist, dentist, medical counselor, nutritionist, and physiotherapist.

cIncludes contact tracers, ambulance crew, burial workers, cleaners, and swabbers (persons taking post mortem skin/mucosal swabs for Ebola testing).

dCurrent occupation information was updated for deferred crossover participants during the crossover period. Many were no longer working as the Ebola outbreak subsided, and Ebola response jobs ended. Crossover participants were offered vaccination regardless of work status.

DISCUSSION

The STRIVE trial achieved high participant retention through 6 months of follow-up despite the challenges of implementing a vaccine trial during an ongoing Ebola outbreak in a resource-limited setting. The trial, which enrolled and vaccinated almost 8000 participants, retained more than 92.5% of participants 6 months postenrollment and 97.4% postvaccination. Participation in every monthly interview was less complete, with 68.8% and 70.4% achieving full compliance in postenrollment and postvaccination interviews, respectively. We observed lower retention among Ebola frontline workers. These workers generally held temporary employment positions during the outbreak, and displacement as Ebola facilities closed and response activities slowed towards the end of the outbreak was a sizeable challenge to follow-up. Nonetheless, the strategies used in the STRIVE trial, including collecting extensive locating information, using closed-user-group cell phone technology and hotlines to facilitate communication, and hiring adequate staff who were familiar with the participant population and local areas resulted in overall high retention and should be considered for future trials in low-resource and other emergency settings.

Evaluating and reporting retention in randomized clinical trials is important because high rates of loss to follow-up (in ranges >20%) can compromise the validity of the trial results [7], particularly if the retention rate is different between the study arms. We observed somewhat lower retention among participants randomized to the deferred vaccination group compared with the immediate arm (89.8% vs 95.2%, respectively) in the first 6 months postenrollment. The unblinded design of the STRIVE trial may have contributed to higher postenrollment retention in the immediate vaccination arm because trial staff may have prioritized contacting vaccinated participants—especially early in the study—because of concerns about possible vaccine-associated adverse events. However, we believe the modest difference in retention across trial arms is unlikely to affect the validity of our trial results [3].

Participants vaccinated immediately after enrollment and those vaccinated after a delay of 18–24 weeks had similar high rates of retention, 96.5% and 95.2%, respectively, 6 months postvaccination, suggesting that use of a delayed intervention arm is a feasible option for randomized clinical trials in emergency settings where a placebo control arm would not be feasible. The assurance that the intervention would be offered to everyone enrolled may help to explain our relatively high retention in the deferred arm postenrollment. Clinical trials in the United States have shown that participant retention tends to decline among those randomized to a placebo arm when the intervention is not offered to all at the end of the trial [8].

Retention rates in the STRIVE trial are comparable to those observed in other Ebola vaccine clinical trials conducted during the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, despite different study designs, lengths of follow-up, and participant populations. The World Health Organization “Ebola Ca Suffit” ring vaccination trial [9] in Guinea, which enrolled village residents who were contacts or contacts of contacts of a case, reported 94% participant retention, although follow-up was <3 months. In Liberia, the PREVAIL trial [10] achieved 97.7% retention of 1500 participant volunteers residing in Monrovia at 6 months and 98.3% at 12 months. These 3 West African Ebola vaccine trials all used similar approaches to follow-up: obtaining detailed contact information, providing a study cell phone or trial hotline number, conducting home visits to track defaulters, and employing dedicated staff to conduct follow-up. These results validate the effectiveness of these approaches.

The STRIVE trial invested substantial time and expertise in ongoing community engagement with the Ebola and health facilities and with political and religious leaders in the districts where the trial was implemented. In nonemergency settings, large pediatric trials in Gambia [11, 12] have similarly achieved high follow-up of >90% using such methods, including community engagement and using dedicated follow-up staff to stay in contact with participants through telephone calls and home visits if they missed a follow-up appointment. Other characteristics of the STRIVE trial, such as development of trusting relationships between study staff and participants, rigorous follow-up efforts, and provision of ongoing staff training, have been shown to improve retention in various vaccine trials in the United States and Africa [13–15].

There were challenges to conducting follow-up in a resource-limited setting with a large cohort of participants spread over an expansive geographical area. Rural districts outside of Freetown often had poor cell phone coverage, and there were periods when cellular service was down nationwide. Furthermore, because not all parts of the country are on the national electric grid, participants frequently lacked access to electricity to charge their study cell phone. Home visits were often time-, labor-, and resource-intensive due to poor quality of roads and limited transportation options, especially in the districts. Approximately 1 day per week, trial staff had use of a study car to make field visits, but even then they often had to use motorbikes from the main road to the villages where participants lived due to lack of paved roads. Street names and house numbers were frequently missing in both rural areas and densely populated urban areas, making it difficult to physically locate participants. Because some trial staff were students or recent graduates from urban Freetown who were assigned to rural district locations, they were not always familiar with the people and location of the villages within the districts. Although we noted higher retention at the rural Tonkolili and semiurban Bombali District sites, neither road infrastructure nor differences in participant population explain why these sites were more successful than others.

The ongoing Ebola outbreak also created unique barriers to follow-up. Ebola response activities appropriately took precedence over study activities, so there were times when study procedures had to be modified or even suspended. For example, there were several times during the trial when study staff could not conduct home visits because the village was under quarantine due to an Ebola case. In one district, staff at a large hospital were quarantined for 21 days after being exposed to an Ebola case. Many of these staff members were STRIVE trial participants who consequently could not be contacted for that month’s assessment if they were not reachable by phone.

Perhaps the biggest challenge to follow-up was displacement of participants. Participant characteristics we identified as associated with higher risk of becoming lost to follow-up—specifically, younger age and employment as a frontline Ebola worker—were likely strongly related to displacement. Beginning in November 2015, Ebola facilities began to close and response activities started winding down. Healthcare and frontline Ebola workers, many of whom had moved to the district centers to work on the response, returned to their homes, often in remote villages, making telephone follow-up more difficult and home visits virtually impossible. Many young nurse graduates enrolled in the STRIVE trial while awaiting their government posting, a universal first step after completing training. During follow-up, some received postings to health facilities in remote districts, far from where they had enrolled in the STRIVE trial, where cell phone service was unreliable and home visits unfeasible, posing challenges to retention. Finally, some participants reported that there was less motivation to complete the trial as Ebola receded from the public mind.

CONCLUSIONS

The STRIVE trial maintained high retention of participants, demonstrating the feasibility of a study design with both a deferred vaccination arm and a long follow-up period. Furthermore, conducting safety assessment follow-up using telephone interviews rather than in-person visits facilitated enrollment of a large number of participants across multiple Ebola-affected districts and resulted in high retention and completion rates.

Key lessons learned include the value of the following: (1) collecting extensive locating information, including telephone numbers of close relatives and friends who would know how to reach participants; (2) flexibility to conduct home outreach for defaulter tracking; (3) use of closed-user-group cell phone technology and hotlines to facilitate communication to report illness or a change in contact information; and (4) employing an adequate number of staff who are familiar with the participant population and local areas. Future trials in outbreak settings can consider using these strategies to offer interventions to persons residing in wide geographical areas not tethered to a single clinical site.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We express our gratitude to the trial participants and thanks to the dedicated Sierra Leone Trial to Introduce a Vaccine Against Ebola (STRIVE) staff from COMHAS, University of Sierra Leone, the Sierra Leone Ministry of Health and Sanitation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Sierra Leone Country Office, and the CDC STRIVE teams in Atlanta and Sierra Leone for their tireless work.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Financial suppoort. The trial was funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and the National Institutes of Health, with additional support from the CDC Foundation.

Supplement sponsorship. This work is part of a supplement sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interests. P. D. and C. R. P. report grants from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority during the conduct of the study. All authors have submitted the ICJME Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Presented in part: IDWeek, October 26–30, 2016; Abstract 749; New Orleans, LA.

References

- 1. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Sample size slippages in randomised trials: exclusions and the lost and wayward. Lancet 2002; 359:781–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robinson KA, Dennison CR, Wayman DM, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Systematic review identifies number of strategies important for retaining study participants. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60:757–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Samai M, Seward JF, Goldstein ST, et al. . The Sierra Leone trail to introduce a vaccine against Ebola: an evaluation of rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP vaccine tolerability and safety during the West Africa Ebola outbreak. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:s6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Widdowson MA, Schrag SJ, Carter RJ, et al. . Implementing an Ebola vaccine study—Sierra Leone. MMWR Suppl 2016; 65:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carter RJ, Idriss A, Widdowson MA, et al. . Implementing a multi-site clinical trial in the midst of an Ebola outbreak: lessons learned from the Sierra Leone trial to introduce a vaccine against Ebola. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:s16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Callis A, Carter VM, Albert AP, et al. . Lessons learned in clinical trial communication during an Ebola outbreak: the implementation of STRIVE. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:s40–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fewtrell MS, Kennedy K, Singhal A, et al. . How much loss to follow-up is acceptable in long-term randomised trials and prospective studies?Arch Dis Child 2008; 93:458–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McCarthy-Keith D, Nurudeen S, Armstrong A, Levens E, Nieman LK. Recruitment and retention of women for clinical leiomyoma trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2010; 31:44–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henao-Restrepo AM, Camacho A, Longini IM, et al. . Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial (Ebola Ça Suffit!). Lancet 2017; 389:505–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kennedy SB, Bolay F, Kieh M, et al. . Phase 2 placebo-controlled trial of two vaccines to prevent Ebola in Liberia. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1438–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cutts FT, Zaman SM, Enwere G, et al. . Efficacy of nine-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against pneumonia and invasive pneumococcal disease in The Gambia: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 365:1139–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Idoko OT, Owolabi OA, Odutola AA, et al. . Lessons in participant retention in the course of a randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Res Notes 2014; 7:706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson RE, Williams RD, Nagy MC, Fouad MN. Retention of under-served women in clinical trials: a focus group study. Ethn Dis 2003; 13:268–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kennedy SB, Neaton JD, Lane HC, et al. . Implementation of an Ebola virus disease vaccine clinical trial during the Ebola epidemic in Liberia: design, procedures, and challenges. Clin Trials 2016; 13:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Larson GS, Baseler BR, Hoover ML, et al. . Conventional wisdom versus actual outcomes: challenges in the conduct of an Ebola vaccine trial in Liberia during the international public health emergency. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 97:10–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]