Abstract

Background

The prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations in primary colorectal cancer (CRC) varies with microsatellite instability (MSI) status. The gene expression–based consensus molecular subtypes (CMSs) of CRC define molecularly and clinically distinct subgroups, and represent a novel stratification framework in biomarker analysis. We investigated the prognostic value of these mutations within the CMS groups.

Patients and methods

Totally 1197 primary tumors from a Norwegian series of CRC stage I–IV were analyzed for MSI and mutation status in hotspots in KRAS (codons 12, 13 and 61) and BRAF (codon 600). A subset was analyzed for gene expression and confident CMS classification was obtained for 317 samples. This cohort was expanded with clinical and molecular data, including CMS classification, from 514 patients in the publically available dataset GSE39582. Gene expression signatures associated with KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations were used to evaluate differential impact of mutations on gene expression among the CMS groups.

Results

BRAF V600E and KRAS mutations were both associated with inferior 5-year overall survival (OS) exclusively in MSS tumors (BRAFV600E mutation versus KRAS/BRAF wild-type: Hazard ratio (HR) 2.85, P < 0.001; KRAS mutation versus KRAS/BRAF wild-type: HR 1.30, P = 0.013). BRAFV600E-mutated MSS tumors were strongly enriched and associated with metastatic disease in CMS1, leading to negative prognostic impact in this subtype (OS: BRAFV600E mutation versus wild-type: HR 7.73, P = 0.001). In contrast, the poor prognosis of KRAS mutations was limited to MSS tumors with CMS2/CMS3 epithelial-like gene expression profiles (OS: KRAS mutation versus wild-type: HR 1.51, P = 0.011). The subtype-specific prognostic associations were substantiated by differential effects of BRAFV600E and KRAS mutations on gene expression signatures according to the MSI status and CMS group.

Conclusions

BRAF V600E mutations are enriched and associated with metastatic disease in CMS1 MSS tumors, leading to poor prognosis in this subtype. KRAS mutations are associated with adverse outcome in epithelial (CMS2/CMS3) MSS tumors.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, consensus molecular subtypes (CMSs), BRAF mutation, KRAS mutation, microsatellite instability, prognosis

Key Message

The prognostic and transcriptional impact of BRAFV600E and KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer varies with microsatellite instability status and consensus molecular subtype classification, indicating relevance of performing future prognostic and predictive biomarker analyses within the context of gene expression-based subtypes.

Introduction

Despite major efforts to identify molecular prognostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer (CRC), the TNM staging system remains the mainstay in prognostication and decision of initial patient management. However, disease stage alone cannot predict which patients will benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, as 50% of stage III patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy are cured by surgery alone [1].

The only biomarkers recommended for routine clinical use due to their prognostic properties in CRC are DNA mismatch repair (MMR) status and BRAFV600E mutation [2]. Deficient MMR or microsatellite instability (MSI) is associated with a lower relapse rate and possibly also with resistance to 5-fluorouracil monotherapy [3], and thus limited benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy. BRAFV600E mutations are associated with poorer overall survival (OS) across stages, with the negative prognostic impact being most prominent in microsatellite stable (MSS) and left-sided tumors [4–8].

KRAS mutations are negative predictors of anti-EGFR therapy efficacy in metastatic CRC [9], while the evidence of a prognostic impact is more ambiguous. Studies on stages I–III disease have shown inconsistent associations with survival [10–12] but a recent study indicated a negative prognostic impact after relapse [4]. Stratification according to primary tumor site and MSI status in stages I–III suggests the negative prognostic effect of KRAS mutations to be distinct for left-sided tumors [4, 13] and MSS tumors [7, 14].

The classification of primary CRCs according to the gene expression–based consensus molecular subtypes (CMSs) defines four molecularly and clinically distinct subgroups, and represents a biological stratification framework with great potential in biomarker development [15]. CMS2 and CMS3 display epithelial-like gene expression profiles, whereas CMS1 is associated with immune-infiltration and CMS4 with epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and both exhibit low expression of genes associated with colonic epithelial differentiation [15, 16]. Tumors with MSI and BRAFV600E mutations are enriched in the CMS1-immune subtype and KRAS mutations in the CMS3 epithelial-metabolic subtype. This may indicate diverging oncogenic dependencies between the CMS groups and subtype-specific prognostic significance of the mutations.

Here, we report the distribution and prognostic impact of mutations in the cancer-critical genes KRAS and BRAFV600E according to clinicopathological and molecular variables, including the CMS groups, in a population-based series of primary CRC.

Materials and methods

Patient material

Totally 1197 primary tumor samples from a consecutive series (Oslo-series) of patients treated surgically for stages I–IV CRC at Oslo University Hospital, Norway between 1993 and 2014 were analyzed (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissue was available from patients operated between 1993 and 2003 (n = 761), while fresh frozen samples were available from patients operated between 2005 and 2014 (n = 436). For analysis of CMS-associations, publically available data from a French multi-centre cohort of stages I–IV primary colon cancer (n = 514) was included (Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE39582) [17] (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). A total of 831 patients with confident CMS classification from both cohorts were analyzed.

Mutation analyses

DNA extraction, determination of MSI status, and Sanger sequencing of mutation hotspots in KRAS (exon 2: codons 12 and 13, exon 3: codon 61) and BRAF (codon 600) were performed as previously described [7, 8, 18–20]. The majority of sequencing data was previously published in the referenced papers.

Gene expression analyses and CMS classification

From fresh frozen tumor samples, RNA was extracted and analyzed for gene expression using Affymetrix exon-level microarrays (n = 409), and tumors were classified according to CMS using the classifyCMS.RF-function in the R package CMSclassifier [15] (supplementary Data, available at Annals of Oncology online). Confident CMS classification was obtained for 317 (78%) of the tumors (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

For patients in the GSE39582 dataset, CMS assignments were available for 514 patients and downloaded from the Colorectal Cancer Subtyping Consortium website at SAGE Synapse (https://www.synapse.org/#! Synapse:syn2623706/wiki/67246). Gene expression data, MSI status, BRAFV600E and KRAS mutation status, and clinical data were downloaded from the GEO accession number.

Sample-wise gene set expression enrichment scores for genes previously found to be upregulated in KRAS-mutated CRCs (n = 13 genes) [21], a BRAFV600E mutation signature (n = 163 genes) [22, 23] and a colonic differentiation signature (n = 165 genes) [24] were calculated using the R package GSVA [25].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc.) (supplementary Data, available at Annals of Oncology online). Five-year OS and relapse-free survival were defined according to the guidelines by Punt et al. [26].

Results

Clinicopathological and molecular associations of KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations

Among the 1197 patients with stages I–IV primary CRC in the Oslo-series, KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations were mutually exclusive, with mutation rates of 31% and 16%, respectively (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Previously described clinicopathological and molecular associations were confirmed, including frequent BRAFV600E mutations in MSI, right-sided and poorly differentiated tumors, as well as in females and elderly patients (Table 1). The strong association with MSI was also found on the transcriptional level, based on single-sample enrichment scores of a BRAF-mutant gene expression signature [22, 23], and MSI tumors were highly ‘BRAF-like’ compared with MSS tumors (supplementary Figure S1A, available at Annals of Oncology online). In contrast, when comparing the ‘BRAF-like’ activation level between BRAFV600E-mutated and wild-type tumors, we found that the effect of mutations on the transcriptional activity was larger in MSS tumors than in MSI tumors, which was validated in the French cohort (supplementary Figure S1B and C, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 1.

Distribution of mutations according to clinicopathological and molecular characteristics (Oslo-series, n = 1197)

| Characteristica | Total |

KRAS (n = 1097) |

BRAF (n = 1185) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | mut (%) | P | mut (%) | P | |

| Total | 1197 | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤70 | 493 | 28 | 0.098 | 13 | 0.025 |

| >70 | 704 | 33 | 18 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 563 | 33 | 0.102 | 8 | <0.001 |

| Female | 634 | 29 | 23 | ||

| MSI status | |||||

| MSS | 993 | 35 | <0.001 | 7 | <0.001 |

| MSI | 184 | 10 | 68 | ||

| CMS | |||||

| CMS1 | 63 | 14 | <0.001 | 71 | <0.001 |

| CMS2 | 138 | 30 | 1 | ||

| CMS3 | 54 | 52 | 17 | ||

| CMS4 | 62 | 29 | 10 | ||

| Location | |||||

| Right | 493 | 33 | 0.512 | 32 | <0.001 |

| Left | 369 | 29 | 6 | ||

| Rectum | 312 | 29 | 3 | ||

| Synchronous | 23 | 35 | 22 | ||

| Stageb | |||||

| I | 195 | 27 | 0.043 | 9 | 0.125 |

| II | 475 | 29 | 19 | ||

| III | 327 | 35 | 14 | ||

| IV | 198 | 33 | 20 | ||

| pTb | |||||

| 1 | 46 | 34 | 0.65 | 9 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 193 | 27 | 9 | ||

| 3 | 840 | 32 | 18 | ||

| 4 | 118 | 30 | 20 | ||

| pNb | |||||

| 0 | 723 | 28 | 0.022 | 16 | 0.844 |

| 1 | 316 | 34 | 14 | ||

| 2 | 148 | 36 | 20 | ||

| Differentiation | |||||

| High | 72 | 30 | 0.591 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Medium | 932 | 31 | 13 | ||

| Low | 154 | 27 | 38 | ||

| Mucinous | 10 | 23 | 40 | ||

| Other/NA | 29 | 42 | 7 | ||

| KRAS | |||||

| wt | 758 | 24 | <0.001 | ||

| mut | 339 | 0 | |||

| BRAF | |||||

| wt | 993 | 37 | <0.001 | ||

| mut | 192 | 0 | |||

P values according to Fisher’s exact test unless otherwise stated.

Spearman correlation test.

mut, mutation; wt, wild-type. Statistically significant P values in bold.

BRAF V600E mutations were enriched in the CMS1 subtype in both MSI and MSS tumors in both patient series (total n = 737; supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Among MSS tumors in general, the mutation frequency of BRAFV600E across the two datasets was 4%. However, MSS tumors with the CMS1 phenotype had a mutation frequency of 34% [odds ratio = 21; 95% confidence interval (CI) 8.7–50.4, P < 0.001; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online].

KRAS mutations were most frequent in MSS tumors (Table 1), and single-sample enrichment analysis showed transcriptional upregulation of a KRAS mutant gene signature [21] in MSS tumors compared with MSI tumors (supplementary Figure S3A, available at Annals of Oncology online). Similarly to BRAFV600E, a comparison of the KRAS mutant expression signature between mutated and wild-type tumors showed that the transcriptional effects of KRAS mutations were higher in MSS tumors than in MSI tumors (supplementary Figures S3B and C, available at Annals of Oncology online). Furthermore, KRAS mutations were most frequent in CMS3, also when analyzing MSS tumors exclusively (supplementary Table S2 and Figure S4A and B, available at Annals of Oncology online). However, a comparison of the KRAS mutant gene expression signature between mutated and wild-type MSS tumors revealed the effect of KRAS mutations to be largest in CMS2 in both patient cohorts (supplementary Figure S4C and D, available at Annals of Oncology online).

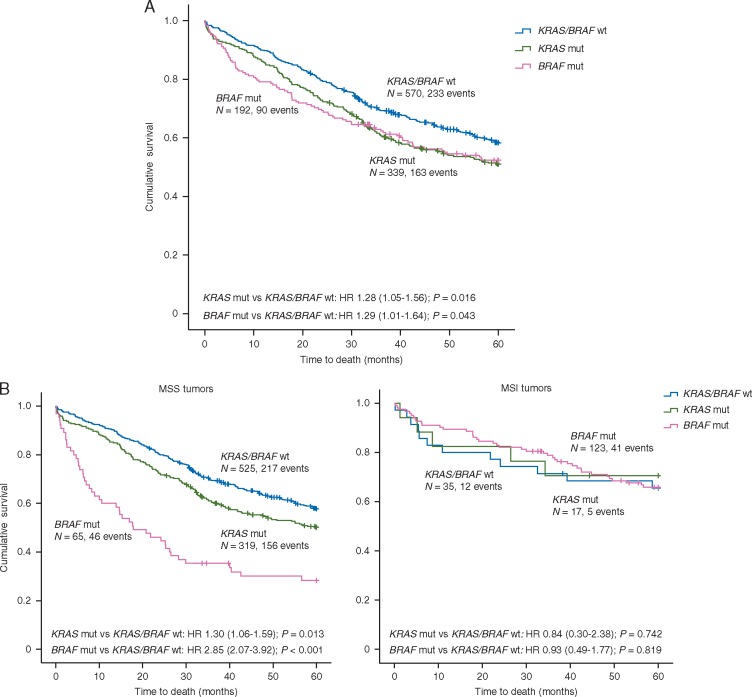

Prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations according to standard clinicopathological and molecular variables

In multivariable analysis in the Oslo-series, patients with BRAFV600E mutation had significantly worse OS (HR 1.61; 95% CI 1.15–2.23; P = 0.005, Table 2, supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online) compared with KRAS/BRAF wild-type. However, the negative prognostic impact was highly specific to the MSS phenotype (MSS: HR 2.85; 95% CI 2.07–3.92; P < 0.001 versus MSI: HR 0.93; 95% CI 0.49–1.77; P = 0.8, Pinteraction = 0.002, Figure 1, supplementary Table S4 and Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online), reinforcing a clinical relevance of the stronger transcriptional effect of the mutations in this population. In MSS tumors, inferior prognosis for patients with BRAFV600E mutation was found both in stages I–III and metastatic disease (supplementary Figure S6, available at Annals of Oncology online), but was distinct for left-sided tumors in multivariable analysis (HR 2.75; 95% CI 1.41–5.38; P = 0.003, supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of prognostic impact (5-year overall survival) of clinicopathological and molecular variables

| Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysisa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Patients, n (%) | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Total | 1197 (100) | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 563 (47) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 634 (53) | 1.03 (0.87–1.23) | 0.713 | 0.91 (0.75–1.11) | 0.362 |

| Age | |||||

| ≤70 | 493 (41) | 1 | 1 | ||

| >70 | 704 (59) | 1.57 (1.31–1.89) | <0.001 | 2.00 (1.63–2.44) | <0.001 |

| MSI status | |||||

| MSS | 993 (84) | 1 | 1 | ||

| MSI | 184 (16) | 0.66 (0.50–0.86) | 0.002 | 0.52 (0.36–0.77) | 0.001 |

| Location | |||||

| Right | 493 (41) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Left | 369 (31) | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 0.574 | 1.02 (0.81–1.29) | 0.877 |

| Rectum | 312 (26) | 0.82 (0.66–1.02) | 0.078 | 0.96 (0.74–1.25) | 0.751 |

| Stage | |||||

| I | 195 (16) | 1 | 1 | ||

| II | 475 (40) | 1.49 (1.07–2.08) | 1.37 (0.95–1.99) | ||

| III | 327 (27) | 2.54 (1.82–3.54) | 2.52 (1.75–3.63) | ||

| IV | 198 (17) | 10.17 (7.30–14.16) | <0.001 | 10.34 (7.18–14.90) | <0.001 |

| Differentiation | |||||

| High | 72 (6) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Medium | 932 (80) | 0.97 (0.68–1.40) | 1.07 (0.70–1.62) | ||

| Lowb | 164 (14) | 1.66 (1.11–2.47) | <0.001 | 1.87 (1.17–3.0) | <0.001 |

| KRAS and/or BRAFc | |||||

| Both wt | 570 (52) | 1 | 1 | ||

| KRAS mut | 339 (31) | 1.28 (1.05–1.56) | 0.016 | 1.21 (0.98–1.49) | 0.08 |

| BRAF mut | 192 (17) | 1.29 (1.01–1.64) | 0.043 | 1.61 (1.15–2.23) | 0.005 |

See supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online, for analyses of relapse-free survival.

Includes all variables in the table. n = 1037, 160 cases dropped due to missing variables.

Includes mucinous.

Includes only patients with conclusive wild type status in both genes or conclusive mutation in one gene.

mut, mutation; wt, wild-type. Statistically significant P values in bold.

Figure 1.

Prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations in unstratified Oslo-series and according to MSI status. Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing 5-year overall survival (OS) for tumors with KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations versus KRAS/BRAF wild-type in (A) the unstratified Oslo-series and (B) stratified according to MSI status. See supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online for analyses of 5-year relapse-free survival.

Patients with tumors harboring KRAS mutations exhibited significantly worse OS compared with patients with KRAS/BRAF wild-type tumors in univariable analysis of the Oslo-series (HR 1.28; 95% CI 1.05–1.56; P = 0.016), while statistical significance was lost in multivariable analysis (Table 2). Stratification according to clinicopathological and molecular variables revealed the negative prognostic impact to be clearly distinct for the MSS subgroup, again reinforcing a clinical relevance of the stronger transcriptional effect of KRAS mutations in this subgroup (MSS: HR 1.30; 95% CI 1.06–1.59; P = 0.013 versus MSI: HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.30–2.38; P = 0.742, Figure 1 and supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). In subsequent multivariable analysis limited to MSS tumors, the inferior prognostic association of KRAS mutation was seen only in left-sided tumors (HR 1.41; 95% CI 0.99–2.02; P = 0.055) and stage IV disease (HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.06–2.29; P = 0.025, supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

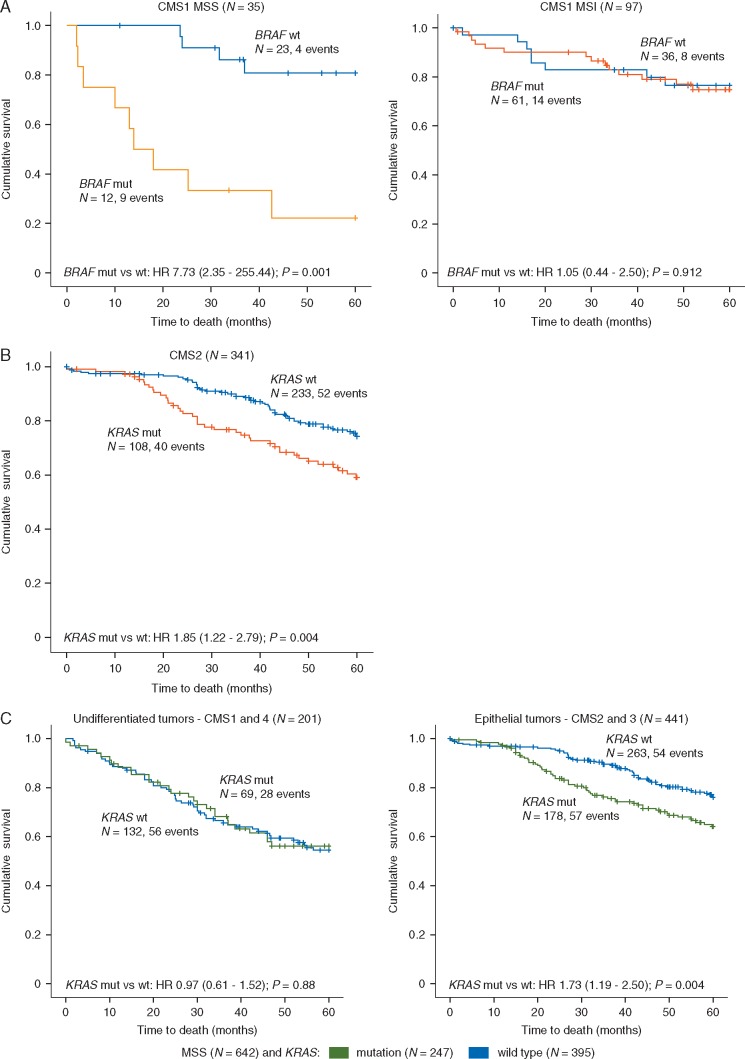

Poor prognostic value of BRAFV600E mutations in MSS tumors is reinforced in CMS1

Analyzing both patient series combined, the poor prognostic impact of BRAFV600E mutations in MSS tumors was found only in CMS1, likely due to the strong mutation enrichment in this subtype (supplementary Figure S7A, available at Annals of Oncology online). Here, patients with BRAFV600E mutations (n = 12) had an OS rate of 22%, significantly lower than the corresponding survival rate of 81% for patients with BRAFV600E wild-type tumors (n = 23; P = 0.001; Figure 2A). This subtype-specific prognostic impact was stronger than for MSS tumors in general (supplementary Figure S7C, available at Annals of Oncology online), and irrespective of tumor location (Pinteraction = 0.8). The poor prognostic association in CMS1 was found in both patient series separately (supplementary Figure S8, available at Annals of Oncology online). However, stratification into early- and late stage disease revealed this association to be mainly driven by an enrichment of metastatic disease in BRAFV600E-mutated CMS1 MSS tumors (supplementary Figure S7D, available at Annals of Oncology online). A similar propensity for metastatic disease of BRAFV600E-mutated tumors was not evident in the other CMS subgroups (supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online). Among MSI tumors, no prognostic association for this mutation was seen within any of the CMS subtypes (supplementary Figure S7B, available at Annals of Oncology online). Consequently, the prognostic impact of BRAFV600E mutations was highly dependent on MSI status within CMS1 (Pinteraction = 0.007).

Figure 2.

BRAF V600E and KRAS mutations are associated with poor patient prognosis in specific CMS groups. (A) In 737 patients with stages I–IV CRC from two independent series (Oslo-series and GSE39582), 35 (5%) had MSS tumors of the CMS1 subtype. Among these patients, BRAFV600E mutations were associated with a poor OS (left panel). No prognostic impact of BRAFV600E mutations was seen in 97 patients with MSI tumors of the CMS1 subtype. (B) In the same set of patients, 341 (46%) had MSS tumors of the CMS2 subtype. Here, KRAS mutations were associated with a poor survival. (C) Analyzing undifferentiated (CMS1 and 4) and epithelial (CMS2 and 3) tumors within the MSS phenotype revealed KRAS mutations to have poor prognostic impact limited to epithelial tumors.

KRAS mutations are associated with adverse outcome for patients with epithelial (CMS2/3) MSS tumors

KRAS mutations were found to have strongest prognostic associations in epithelial (CMS2/3) MSS tumors, with statistical significance only in CMS2 (supplementary Figure S9, available at Annals of Oncology online). Patients with KRAS-mutated CMS2 and MSS tumors (n = 108) had an OS rate of 59%, significantly lower than the corresponding 75% survival rate for patients wild-type for KRAS (n = 233; P = 0.004; Figure 2B). A nonsignificant trend was retained in multivariable analysis (HR 1.32; 95% CI 0.83–2.10; P = 0.249). The prognostic association in CMS2 was similar for left- and right-sided MSS tumors (Pinteraction = 0.326, supplementary Figure S10, available at Annals of Oncology online) and limited to stages I–III (OS: HR 2.09; 95% CI 1.29–3.38; P = 0.003, supplementary Figure S11, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Based on single-sample enrichment scores of a colonic differentiation signature, CMS1/4 and CMS2/3 were confirmed to display undifferentiated and epithelial-like gene expression profiles, respectively (supplementary Figure S12, available at Annals of Oncology online). KRAS mutations were weakly associated with poor survival also in CMS3 MSS tumors (OS: HR 3.77; 95% CI 0.87–16.34; P = 0.076), and there was a clear difference in the prognostic impact between epithelial CMS2/3 cancers and undifferentiated CMS1/4 cancers (Figure 2C).

Discussion

In a large single-hospital series of primary CRCs, we confirm previous findings that the prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations is specific to MSS tumors [4–8, 10, 14, 27], and show that this is associated with a greater transcriptional effect of both mutations in the MSS subgroup. Integration with CMS classification reveals that the poor prognostic associations of BRAFV600E mutations in MSS are strengthened among CMS1 tumors. This is likely due to strong mutation enrichment in this subtype and a propensity for metastatic disease among the mutated tumors. For KRAS mutations, the negative prognostic impact is limited to epithelial (CMS2/3) tumors. These novel context-dependent prognostic associations are irrespective of primary tumor location and for KRAS mutations, biologically substantiated by the varying transcriptional effect of the mutations according to the CMS group.

Preclinical studies have shown KRAS oncogenic dependency to be strongly linked to epithelial differentiation [28]. Our finding that KRAS mutations have specific negative prognostic impact within CMS2 and CMS3, translates these observations into a clinical setting. The biological mechanism for KRAS mutations having stronger prognostic significance in CMS2 than CMS3 is unclear, and may partially be explained by the limited number of patients in the MSS CMS3 subgroup. We hypothesize that KRAS dependency is a hallmark of most CMS3 tumors regardless of mutation status, as indicated by the lesser effect of KRAS mutations on its corresponding gene expression signature in CMS3 compared with CMS2. Furthermore, mutations outside the known hotspots analyzed in this study, in addition to in NRAS and HRAS, may be differentially distributed across the CMS groups and could influence the survival analysis. However, the CMS2 subgroup is particularly sensitive to EGFR blockade in preclinical models [29], indicating that this subtype is particularly susceptible to alterations in this signaling pathway. Negative prognostic value of KRAS mutations in CMS2 may also be explained by recent results showing reduced immune reactivity in this patient subgroup [30].

The efficacy of targeting the MAP kinase pathway in BRAFV600E mutant CRC has remained inferior to results in malignant melanoma [31]. Still, such treatment is active in a subset of CRC patients, in particular when combined with EGFR and/or MEK inhibition, but no molecular characteristics predicting treatment efficacy have been identified. Our finding of BRAFV600E mutations potentially having varying prognostic effect according to the CMS and MSI status possibly reflects phenotype-dependent oncogenic impact, and could point to a biological association with predictive relevance.

For both KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations, the magnitude of the prognostic effect is gradually increased as analysis is performed within the biologically relevant subgroups, emphasizing the clinical relevance of integrated molecular models for prognostic assessment. BRAFV600E mutations have stronger prognostic effect than KRAS mutations, and this study clearly indicated BRAFV600E mutations to be a more crucial oncogenic driver with pronounced transcriptomic and prognostic consequences, when analyzed within the correct phenotype. However, a caveat of performing biomarker analysis within increasingly stratified subgroups is the corresponding reduction in sample size and statistical power. Notably, multiple testing is not corrected for in our study. BRAFV600E mutations are infrequent among MSS tumors, and the lacking prognostic impact of BRAFV600E mutations in CMS2-4 could be due to the low numbers of mutated tumors within these subtypes. The differential prognostic impact of BRAFV600E mutations according to MSI status within CMS1 is more convincing. This supports the notion that the prognostic effect of these mutations depends more on the mutator phenotype than the extent of immune infiltration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, by incorporation of CMS classification, novel subtype-specific prognostic associations of the extensively studied KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations in primary CRC were indicated. However, due to the small sample sizes within certain subgroups, the results must be interpreted with caution. If validated, these findings could have clinical implications, and suggest relevance of interpreting the prognostic and predictive value of molecular aberrations within the context of gene expression–based subtypes in biomarker research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the excellent technical assistance with DNA sequencing by Mette Eknæs and Merete Hektoen.

Funding

Norwegian Cancer Society (project numbers 6824048-2016 to AS and 182759-2016 to RAL); the foundation Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen (RAL); the Research Council of Norway (FRIPRO Toppforsk, project number 250993, grants to the Norwegian Cancer Genomics Consortium, both RAL).

Disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS. et al. Fluorouracil plus levamisole as effective adjuvant therapy after resection of stage III colon carcinoma: a final report. Ann Intern Med 1995; 122(5): 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sepulveda AR, Hamilton SR, Allegra CJ. et al. Molecular biomarkers for the evaluation of colorectal cancer: guideline from the American Society for Clinical Pathology, College of American Pathologists, Association for Molecular Pathology, and American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Mol Diagn 2017; 19(2): 187–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guastadisegni C, Colafranceschi M, Ottini L, Dogliotti E.. Microsatellite instability as a marker of prognosis and response to therapy: a meta-analysis of colorectal cancer survival data. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46(15): 2788–2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sinicrope FA, Shi Q, Allegra CJ. et al. Association of DNA mismatch repair and mutations in BRAF and KRAS with survival after recurrence in stage III colon cancers: a secondary analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(4): 472–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Samowitz WS, Sweeney C, Herrick J. et al. Poor survival associated with the BRAF V600E mutation in microsatellite-stable colon cancers. Cancer Res 2005; 65(14): 6063–6069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lochhead P, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y. et al. Microsatellite instability and BRAF mutation testing in colorectal cancer prognostication. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105(15): 1151–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dienstmann R, Mason MJ, Sinicrope FA. et al. Prediction of overall survival in stage II and III colon cancer beyond TNM system: a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(5): 1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vedeld HM, Merok M, Jeanmougin M. et al. CpG island methylator phenotype identifies high risk patients among microsatellite stable BRAF mutated colorectal cancers. Int J Cancer 2017; 141(5): 967–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R. et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(8): 1386–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M. et al. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28(3): 466–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mouradov D, Domingo E, Gibbs P. et al. Survival in stage II/III colorectal cancer is independently predicted by chromosomal and microsatellite instability, but not by specific driver mutations. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(11): 1785–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Cunningham D. et al. Kirsten ras mutations in patients with colorectal cancer: the ‘RASCAL II’ study. Br J Cancer 2001; 85(5): 692–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blons H, Emile JF, Le Malicot K. et al. Prognostic value of KRAS mutations in stage III colon cancer: post hoc analysis of the PETACC8 phase III trial dataset. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(12): 2378–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taieb J, Le Malicot K, Shi Q. et al. Prognostic value of BRAF and KRAS mutations in MSI and MSS stage III colon cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 2017; 109(5): djw272–djw272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X. et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21(11): 1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trinh A, Trumpi K, De Sousa EMF. et al. Practical and robust identification of molecular subtypes in colorectal cancer by immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(2): 387–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marisa L, de Reynies A, Duval A. et al. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med 2013; 10(5): e1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merok MA, Ahlquist T, Royrvik EC. et al. Microsatellite instability has a positive prognostic impact on stage II colorectal cancer after complete resection: results from a large, consecutive Norwegian series. Ann Oncol 2013; 24(5): 1274–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berg M, Danielsen SA, Ahlquist T. et al. DNA sequence profiles of the colorectal cancer critical gene set KRAS-BRAF-PIK3CA-PTEN-TP53 related to age at disease onset. PLoS One 2010; 5(11): e13978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sveen A, Johannessen B, Tengs T. et al. Multilevel genomics of colorectal cancers with microsatellite instability-clinical impact of JAK1 mutations and consensus molecular subtype 1. Genome Med 2017; 9(1): 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watanabe T, Kobunai T, Yamamoto Y. et al. Differential gene expression signatures between colorectal cancers with and without KRAS mutations: crosstalk between the KRAS pathway and other signalling pathways. Eur J Cancer 2011; 47(13): 1946–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Popovici V, Budinska E, Tejpar S. et al. Identification of a poor-prognosis BRAF-mutant-like population of patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(12): 1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tian S, Simon I, Moreno V. et al. A combined oncogenic pathway signature of BRAF, KRAS and PI3KCA mutation improves colorectal cancer classification and cetuximab treatment prediction. Gut 2013; 62(4): 540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM. et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015; 347(6220): 1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanzelmann S, Castelo R, Guinney J.. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-Seq data. Bmc Bioinformatics 2013; 14: 7.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Punt CJ, Buyse M, Kohne CH. et al. Endpoints in adjuvant treatment trials: a systematic review of the literature in colon cancer and proposed definitions for future trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99(13): 998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sinicrope FA, Shi Q, Smyrk TC. et al. Molecular markers identify subtypes of stage III colon cancer associated with patient outcomes. Gastroenterology 2015; 148(1): 88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Singh A, Greninger P, Rhodes D. et al. A gene expression signature associated with “K-Ras addiction” reveals regulators of EMT and tumor cell survival. Cancer Cell 2009; 15(6): 489–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sveen A, Bruun J, Eide PW. et al. Colorectal cancer consensus molecular subtypes translated to preclinical models uncover potentially targetable cancer cell dependencies. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24(6): 794–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lal N, White BS, Goussous G. et al. KRAS mutation and consensus molecular subtypes 2 and 3 are independently associated with reduced immune infiltration and reactivity in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2017; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Corcoran RB, Atreya CE, Falchook GS. et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition with dabrafenib and trametinib in BRAF V600-mutant colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(34): 4023–4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.