Abstract

Cell volume regulation is fundamentally important in phenomena such as cell growth, proliferation, tissue homeostasis, and embryogenesis. How the cell size is set, maintained, and changed over a cell’s lifetime is not well understood. In this work we focus on how the volume of nonexcitable tissue cells is coupled to the cell membrane electrical potential and the concentrations of membrane-permeable ions in the cell environment. Specifically, we demonstrate that a sudden cell depolarization using the whole-cell patch clamp results in a 50% increase in cell volume, whereas hyperpolarization results in a slight volume decrease. We find that cell volume can be partially controlled by changing the chloride or the sodium/potassium concentrations in the extracellular environment while maintaining a constant external osmotic pressure. Depletion of external chloride leads to a volume decrease in suspended HN31 cells. Introducing cells to a high-potassium solution causes volume increase up to 50%. Cell volume is also influenced by cortical tension: actin depolymerization leads to cell volume increase. We present an electrophysiology model of water dynamics driven by changes in membrane potential and the concentrations of permeable ions in the cells surrounding. The model quantitatively predicts that the cell volume is directly proportional to the intracellular protein content.

Introduction

Cells live in dynamic environments to which they must adapt (1, 2, 3). In both physiological and pathological conditions, cells can respond to cytokines and other types of signals by changing their sizes (4, 5, 6, 7). Cell volume changes can also trigger apoptosis, regulatory volume decrease, cell migration, and cell proliferation (8, 9, 10). Although it is well known that osmotic pressure differences can cause cell swelling or shrinkage, changes in mechanical forces experienced by the cell can also influence cell volume (11). For instance, active mechanical processes in the cell cytoskeleton, such as myosin contraction, generate contractile forces that impact cell volume regulation (12, 13). Sudden changes in external hydrostatic pressure can change cell volume on the timescale of minutes (14). Mathematical models of cell volume regulation have shown that there is a dynamic interplay among water flow, ionic fluxes, and active cytoskeleton contraction; all of these processes combine to influence cell mechanical behavior (15). But many questions remain: What are the factors determining homeostatic cell volumes? How are cells able to sense volume changes? Moreover, cells live in saline environments where there are high concentrations of charged ions that are able to flow under electrical potential gradients. It has been shown that changing the transmembrane potential of nonexcitable cells can affect cell shape, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and intercellular signaling (16, 17). Because many of the same processes control both the cell osmotic pressure and membrane potential, we ask whether cell volume is closely coupled to membrane potential or the ionic environment. Indeed, cell volume changes have been observed when the ionic environment of the medium is modulated by applied electrical fields (18). Previous experiments have explored shape changes in cells due to specific ionic currents or ion channels/pumps, e.g., the effects of Ca2+ on shape oscillations (19, 20) and regulatory volume decrease due to SWELL channels (21, 22, 23). These studies do not treat the cell as an electro-chemo-mechanical system, but instead focus on specific signaling networks or ionic currents. In this article, we aim to understand how mechanical, electrical, and chemical systems work together, with primary focus on the most abundant principal ionic components sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), and chloride (Cl−).

We first address whether the cell volume is related to the transmembrane electrical potential (Fig. 1). We perform whole-cell patch-clamp experiments (24) on suspended head-neck squamous carcinoma cells (HN31) and correlate transmembrane voltage with the cell volume. After discovering that cell volume is modulated by the membrane potential, we seek a less intrusive manner to modify the cell’s electrical environment. For example, changing the concentration of an ionic species in a cell’s environment may change the cell’s membrane potential (25, 26). In this case, because the membrane potential is not enforced by means of the patch-clamp technique, the cell is now able to modify its internal ionic content and readjust its membrane potential. We can thus measure the volume of suspended cells and try to determine how cell size is affected by changes in the ionic environment. We also use a microfluidic compression device (27) to hold nonadherent cells in place, and measure cell volumes in parallel with changes in the cell environment. We also investigate the role of the actin cytoskeleton in volume regulation. In parallel, we develop a mathematical model to explain cell volume as a function of transmembrane voltage and ionic content. Active ion pumps as well as passive channels and cotransporters are involved in ionic fluxes across the membrane. We propose from both experimental data and the model that the cell volume is mainly the result of the total amount of intracellular ions and proteins. The model predicts that the cell keeps a constant concentration of major ions. As the protein content grows, the cell volume scales proportionally.

Figure 1.

Cell volume regulation on short timescales is closely related to ionic regulation. Major ion species in the cell are Na+, K+, and Cl−, which are all present in millimolar concentrations. These ion concentrations are controlled by passive ion channels and active ion pumps. Changes in ionic content also influence the transmembrane potential. In experiments, the membrane potential can be controlled by introducing external currents using a voltage clamp. The cell volume, which is determined by the overall water and protein content, can be modulated by changes in the transmembrane potential, external ionic content, or cortical tension. To see this figure in color, go online.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HN-31, a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic cell line, was cultured in DMEM (11960044; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 1% L-glutamine (17-605E; Lonza Group, Basel, Switzerland), 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin solution (SV30010 and HyClone; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2% MEM vitamin solution (SH30599.01; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% sodium pyruvate solution (SH30239.01 and HyClone; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% nonessential amino acids (13-114E; Lonza Group), and 10% FBS. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 atmosphere and grown to 70–80% confluence.

Experimental solutions

The bath solution used during voltage clamp by whole-cell patch-clamp recording was a modified Ringer’s solution chosen to resemble the physiological environment. It consisted of 140 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES. The pH was titrated to 7.25 with NaOH (final concentration ∼1.5 mM), and the osmolality was adjusted to 300 mOsm/kg by addition of glucose (15 mM). The internal solution used to fill the quartz pipettes was chosen to mimic the physiological contents of the cell. It consisted of 135 mM K-glutamate, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM Na2-ATP, 10 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES. The pH was adjusted to 7.25 with KOH (final concentration 9.4 mM), and the osmolality was 316 mOsm/kg. The potassium glutamate was made by titrating glutamic acid with potassium hydroxide. All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Microfluidic solutions were based on the modified Ringer’s solution, with additional experiment-specific modifications: The low-chloride solution was identical to the modified Ringer’s solution, except the 140 mM NaCl were substituted with 140 mM Na-aspartate, because aspartate is a negatively charged amino acid, too large to pass through most ion channels and pumps. For the high-potassium solution, the amounts of KCl and NaCl were switched, so that the solution consisted of 2.8 mM NaCl and 140 mM KCl. For the actin depolymerization experiments, 1 μM Latrunculin A (Lat. A) was added to the modified Ringer’s solution. A detailed list of the solution content is in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental Solutions

| Internal |

Modified |

Low |

High |

Actin |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patch | Ringer’s | Cl− | K+ | Depolymerization | |

| NaCl | 0 | 140 | 0 | 2.8 | 140 |

| Na-aspartate | 0 | 0 | 140 | 0 | 0 |

| K-glutamate | 135 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KCl | 0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 140 | 2.8 |

| MgCl2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CaCl2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| HEPES | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| NaOH | 0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| KOH | 9.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Na-ATP | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| EGTA | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Latrunculin A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10−3 |

Given in micromolar.

Microscopy

For voltage-clamp whole-cell patch-clamp experiments, HN-31 cells were imaged with bright-field illumination (oil immersion 100× objective lens on a Axiovert 135 microscope; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). A video camera (model No. NC-70×; DAGE-MTI, Michigan City, IN) and videocassette recorder (model No. AG-1970, S-VHS; Panasonic, Secaucus, NJ) were used to monitor and record (33 frames/s) the transmission image of cells over the duration of the experiment. The images were digitized and used to obtain the morphology of the cell (i.e., cell radius). For each frame of each experiment, a circle, parameterized by its radius and center, was fit to the cell by hand. Cells whose images could not be parameterized as a circle (i.e., cells with bleb formations) were excluded from the analysis.

For microfluidic experiments, HN31 cells were imaged with a confocal microscope (oil immersion 63 objective LSM 780 microscope; Zeiss). Cells were illuminated with a 405-nm photodiode, and the emitted 460- and 580-nm fluorescence was detected by photomultiplier tubes. Images were acquired every 4 min to avoid photobleaching during the course of the experiment. After obtaining 80 min of time-series images, confocal slices 1 μm apart were obtained for every cell.

For the chloride experiment on suspended cells, a 60× microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and a camera (model No. 26100-230 miniVUE camera; Aven Tools, Ann Arbor, MI) were used to image the suspended cell every 15 s.

Whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments

For each voltage-clamp experiment the cells were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended in fresh media. The cells were reseeded on top of a 35-mm poly-D-lysine-coated glass-bottom Petri dish (MaTek, Ashland, MA) suspended in modified Ringer’s solution. Experiments were conducted before the cells attached to the substrate, within ∼10 min after reseeding. This ensured that the cells remained spherical, allowing estimation of volume from radius measurements. The Petri dish was perfused with Ringer’s solution with a peristaltic pump (model No. RP-1 4 channel pump; Rainin, Oakland, CA) at a constant flow rate of 0.5 mL/min.

Quartz pipettes were pulled with a laser-based puller (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA) and coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning, Midland, MI); they had resistances of <10 MΩ. A single suspended cell was chosen for an experiment. The suspended cell was attached to the quartz pipette by applying negative pressure to the pipette, and the pipette pressure was controlled during giga-seal formation as well as during recordings with a high-speed pressure clamp (model No. HSPC-1; ALA Scientific Instruments, Farmingdale, NY). Voltage clamp of the cell’s membrane potential was maintained with an amplifier (model No. Axon 200B; Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) configured in whole-cell patch-clamp mode. Voltages were measured relative to a reference electrode (Ag/AgCl) that was placed in the bath. The holding potential was maintained while recording the cell morphology, where the pipette pressure was held approximately constant at −0.9 mmHg. For the entire duration of the recording, a 5 mV amplitude square-wave was added to the holding potential to monitor the DC conductance of the cells. The voltage stimulus and data acquisition were controlled by software written in LabVIEW for Windows (v8.5.1; National Instruments, Austin, TX) in conjunction with a digital acquisition card (model No. PCI-6052E; National Instruments), and the data analysis were preformed using MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Microfabrication of microfluidic compression device

The compression device is able to maintain the cells in the same position under external fluid flow (27). Silicon wafers were patterned with SU8-2100 (MicroChem, Westborough, MA), using UV exposure and photomasks (Fineline Imaging, Colorado Springs, CO). Wafers were created for the cell and air chambers, which were fabricated with PDMS (Sylgard 184; Dow Corning). Using another mask and UV exposure, micropillars of 10–15-μm tall were printed directly onto a glass coverslip from SPR220-7, using the adhesion promoter Hexamethyldisilazane (Sigma-Aldrich). Holes were punched into the air chamber layer, which was then aligned with the cell chamber layer. The layers were bonded by baking at 80°C. The inlet and outlet holes to the cell chamber were then punched into the PDMS, the cell and air chambers were aligned with the micropillar layer, and the PDMS was bonded to the cover glass with plasma treatment and baking at 80°C overnight before use.

Microfluidic experiments

Microfluidic devices were incubated with 100 mg/mL BSA before cell loading to decrease cell adhesion to the glass. After remaining in the microfluidic device for at least 30 min, the BSA was removed from the device, and the cell chamber was rinsed with modified Ringer’s solution.

The microfluidic device was arranged on the microscope stage, and the air pressure in the device’s air chamber was adjusted to ∼25 psi to compress the cells. An electric syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, MA) was attached to the cell chamber inlet and outlet to induce solution flow through the cell chamber. After compression, the flow was set to ∼80 μL/min to flush out any small, uncompressed cells and cell debris and to continuously refresh the cells’ environment.

After ∼30 min, the external solution supplied by the syringe pump was changed to low-sodium/high-potassium solution.

Chloride concentration experiments

HN31 cells grown in culture were trypsinized and resuspended in fresh media. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in the modified Ringer’s solution described above. Glass, fire-polished pipettes were filled with Ringer’s solution and were attached to micromanipulators. The suspended cells were attached to the pipette by applying negative pressure inside the pipette. Unlike the patch-clamp experiment, the chloride concentration experiments did not use the whole-cell voltage-clamp configuration; rather, the pipette was simply used to hold a single cell in suspension while measuring its size. During this process, the cell bath was slowly refreshed with the low-chloride solution at a flow rate of ∼3 μL/min.

Mathematical model

Here we present a mathematical model that relates the cell’s electrical physiology to the cell volume through the regulation of ion fluxes and intracellular osmotic content. This model is motivated by the observation that the cell volume is correlated to the transmembrane voltage and the extracellular ionic environment. The model focuses on osmolarity regulation through ionic contributions on short timescales, and ignores longer timescale changes in cell cytoskeletal organization and contractility. By their relative contributions to the intracellular osmolarity, we consider four ionic species, Na+, K+, Cl−, and A−, in the model, where A− represents negatively charged large molecules or proteins that are not permeable across the cell membrane. The extracellular ion concentrations, , are given according to the specification of each experiment. Here c represents concentrations, the superscript “0” indicates quantities associated with the extracellular environment, and . The total number of intracellular proteins, NA, is given, but its effective valence is unknown and is thus assumed. Without loss of generality, we assume the average valence of these molecules to be −1. Multivalent ions such as Ca2+ and Mg2+ are also important in many cellular processes. In this model, however, we do not include them because their free cytoplasmic concentrations are much lower than the above four species (25, 28), and thus their relative contributions to the intracellular osmolarity can be neglected.

At short timescales (approximately minutes), changes in the cell size are mainly determined by water transport; therefore the radius of a spherical cell, r, is given by (15)

| (1) |

where Jwater is the water flux across the cell membrane, defined as positive inward. The parameter α is the coefficient of water permeation; ΔΠ is the osmotic pressure difference across the cell surface; and the hydrostatic pressure difference across the cell surface, Δp, is related to the cortical stress, σ, by the Laplace law

| (2) |

where h is the thickness of the cell cortex. The cortical stress can be solved from constitutive equations of the actomyosin cortex (15)

| (3) |

where is the passive mechanical stress of the actin network, which includes contributions from F-actin cross-linkers and filament mechanics, and is the active myosin contraction from the cortex. The passive stress is likely small when compared to the active stress (29). The cortical stress is also influenced by calcium flux (19, 30, 31) and may, therefore, change with the membrane potential. We assume that this change is secondary when compared to the Lat. A treatment. In this model, we consider as a parameter.

The governing equation for the total amount of each intracellular ion species, , is

| (4) |

where is the total ion flux across the membrane for each species and is determined by the boundary conditions of ion fluxes through the membrane channels. In general, ions are transported across the membrane both passively and actively. Passive ionic transport is carried out by ion-specific channels and pores, some of which are gated by membrane tension, . Active transport is carried out by energy-consuming ion pumps, which utilize chemical energy (e.g., ATP) to transport ions against a chemical potential gradient. Both modes of transport are incorporated in our model:

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

The passive ion fluxes, , are proportional to the electrochemical potential difference of ions across the membrane (32),

| (8) |

where is the ratio of extra- to intracellular ion concentrations; Vm is the membrane potential across the cell; R is the gas constant; T is the absolute temperature; F is the Faraday’s constant; is the rate of ion permeation of each species, where is a flux rate constant that depends on the channel property and the density of the channels; and is a mechanosensitive gating function that follows a Boltzmann distribution, i.e.,

| (9) |

where and are two constants.

Another channel to consider is the Na+-K+-Cl− cotransporter (NKCC) which, along with its isoforms, is widely expressed in various cell types (33). NKCC simultaneously transports one Na+, one K+, and two Cl−s into the cell under physiological conditions, the flux of which can be written as (34)

| (10) |

where is a transport rate constant independent of the membrane tension. Here we have also assumed that this flux is independent of the membrane potential.

For active fluxes, we consider the Na+/K+ pump, a ubiquitous and important ion pump in animal cells. It exports three Na+ ions and intakes two K+ ions per ATP unit. Because the overall flux is positively charged, the activity of the pump depends on the membrane potential (35). In addition, the flux depends on the concentrations of Na+ and K+ (36, 37) and saturates at high-concentration limits (37). By decoupling the dependence of the voltage and ion concentrations, as a modification of existing models (37, 38), we express the fluxes of Na+ and K+ through the Na+/K+ pump as

| (11) |

where αATP is a transport rate constant of the pump; cATP is the concentration of ATP; and are constants that scale and , respectively; and the exponents 3 and 2 are the Hill’s coefficients of Na+ and K+, respectively. Eq. 11 ensures that the flux is zero when either or goes to zero; the flux saturates if and go to infinity. captures the voltage-dependence of the pump activity (35)

| (12) |

where and are constant.

The equation for the membrane potential is solved by the electro-neutral condition, i.e.,

| (13) |

where is the valence of each ionic species. The electro-neutral condition also applies to the extracellular medium. In addition to the experiment-specified , we also add either positively or negatively charged large molecules to balance the total charge in the medium. The added molecules contribute to extracellular osmolarity as well.

At steady state, . The unknowns are r, , , , and Vm. Equations 1, 4, and 13 are used to solve the five unknowns.

Under a voltage clamp where the membrane potential is set externally, the unknowns of the system are r, , , , and Jclamp, and Eqs. 5, 6, and 7 are replaced by

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

where Jclamp is an additional current introduced by an external electrode. Without the electrode in the voltage clamp experiment, Jclamp is absent. As an approximation, we attribute this current to a sodium flux. One can also model this current as an additional cation flux into the cell and similar model results are obtained. The cell responds to membrane potential changes by adjusting the sodium, potassium, and chloride fluxes; these adjusted fluxes are different from the added Jclamp from the presence of the electrodes.

Unless otherwise specified, the parameters in the model are listed in Table 2. These parameters may vary from cell line to cell line, and even within a same cell line when cells are cultured in different environments. As expected, parameters associated with ion fluxes or ion concentrations play a direct role in determining the steady intracellular ion concentrations, whereas the time-dependent cell response is only sensitive to permeation and rate parameters. Because all the components of the model are physiologically based, the model works best when parameters or environments of the cell are physiologically relevant. Within physiological regimes, the model is robust in a sense that a finite change of parameters leads to a finite change in the cell response.

Table 2.

Parameters Used in the Electromotility Model

| Parameters | Description | Values | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| R (J/mol/K) | ideal gas constant | 8.3145 | physical constant |

| T (K) | absolute temperature | 300 | room temperature |

| F (C/mol) | Faraday’s constant | 96,485.3 | physical constant |

| (μm) | initial cell radius | 9.1 | average value in the experiment |

| h (μm) | effective cortical thickness | 0.5 | (15) |

| (Pa) | passive membrane stress | estimated from force balance | |

| (Pa) | active contraction | estimated from force balance | |

| (mol) | total intracellular area | estimated from intracellular osmolarity | |

| α (m/s/Pa) | water permeability | (15, 46) | |

| (mol2/Kg/m3) | Na channel constant | based on (25) | |

| (mol2/Kg/m3) | K channel constant | fitting parameter | |

| (mol2/Kg/m3) | Cl channel constant | based on (25) | |

| (mol/m3) | ATP concentration | 1 | fitting parameter |

| (m/s) | coefficient in | 0.1 | fitting parameter |

| constant in | 0.01 | fitting parameter | |

| constant in | 0.1 | fitting parameter | |

| (mol/m2/s) | coefficient in | fitting parameter | |

| constant in | 10 | fitting parameter | |

| (N/m) | constant in | fitting parameter | |

| constant in | 1.5 | fitting parameter | |

| (mV) | constant in | fitting parameter |

Results and Discussion

Cell volume increases with direct depolarization

We used whole-cell patch clamp to obtain electrical access to the cytoplasm of the cell. Using suspended cells enabled us to measure cell size with bright field illumination, from which cell volume could be estimated due to their spherical geometry. For the initial experiments the membrane potential of the cell was clamped at −60 mV, a typical resting potential for cells (39), for ∼20 min, allowing the volume of the cell to equilibrate. We then changed the potential to either −120, −90, −30, or 0 mV. After every change in potential, we waited 10–20 min for the cell volume to readjust. A typical cell completes its response to voltage change in 10 min (Fig. 2 A). We find that the cell volume increases monotonically with increasing transmembrane voltage (Fig. 2 B). The cell overall volume increase is roughly 50% when the membrane potential is zero (Fig. 2 B). We also find that the decrease of cell volume upon hyperpolarization is less significant than the increase of the volume upon depolarization.

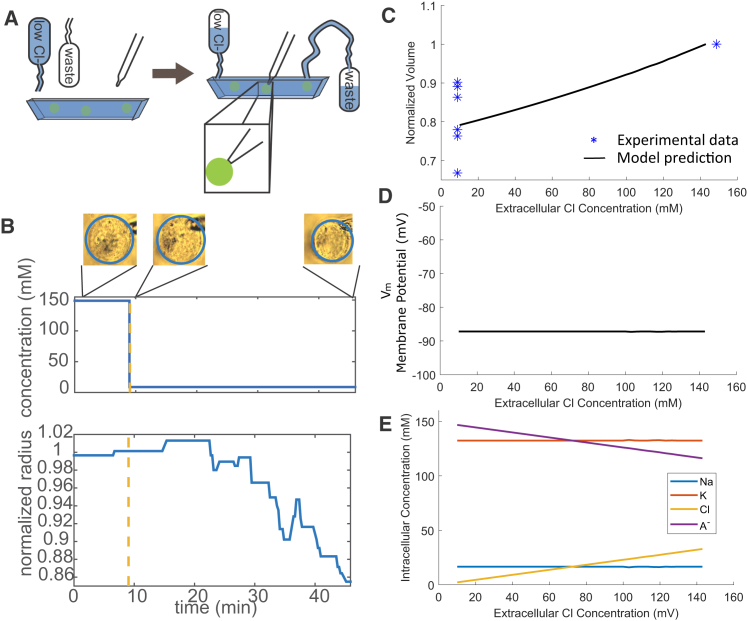

Figure 2.

Cell volume correlates with the transmembrane potential. (A) As the membrane holding potential is changed (upper panel), the cell radius and volume change with time (lower panel). The data is shown for one cell for illustration. (B) Shown here is the measured steady-state cell volume-versus-transmembrane potential after the cell has completed its response. Cell volume is normalized with respect to the volume at −60 mV. The volume increases with depolarization. (Star) Shown here is the experimental data. Different colors represent different cells (N = 10). The following are the significance of cell volume change for each voltage condition when compared to Vm = −60 mV according to the Student t-test. 0 mV: p = 0.0010, n = 7; −90 mV: p = 0.5496, n = 5; −110 mV: p = 0, n = 2; −120 mV: p = 0.0408, n = 6. (Solid line) Given here is the model prediction. (C) Model prediction is shown on the intracellular concentrations of the four species as functions of the membrane potential. To see this figure in color, go online.

The observed relation between the membrane potential and the cell volume can be predicted by our electromechanical model (Fig. 2 B). The model suggests that as the cell is depolarized and its volume increases, the concentrations of Na+ and K+ almost remain the same (Fig. 2 C), showing that in addition to Cl− influx upon depolarization, Na+ and K+ also flow into the cell. An increased concentration of Cl− suggests a decreased concentration of A− because the electro-neutral condition must be satisfied. The decreased concentration of A− can only happen when the cell volume increases, as seen in the experiment and predicted by the model. Consistent with the experimental data, the model also shows that the cell volume decrease is less significant upon hyperpolarization than the volume increase upon depolarization.

Cell volume decreases with decreased extracellular chloride concentration

Because ion flux is involved in cell volume regulation, we next ask if it is possible to control cell volume by changing the chemical potential of membrane-permeable ions in the cell’s environment. Given that chloride is the only abundant negatively charged ion in the cell medium, we would like to examine the effect of extracellular chloride concentration on the cell volume. In this experiment we replaced 140 mM of chloride in the modified Ringer’s solution with aspartate, a negatively charged ion that is too large to pass through the cell membrane (Fig. 3 A). To avoid effects of shear stress from the fluid onto the cell, we gradually replaced the high-concentration chloride solution with the high-concentration aspartate solution instead of implementing a step change in solution.

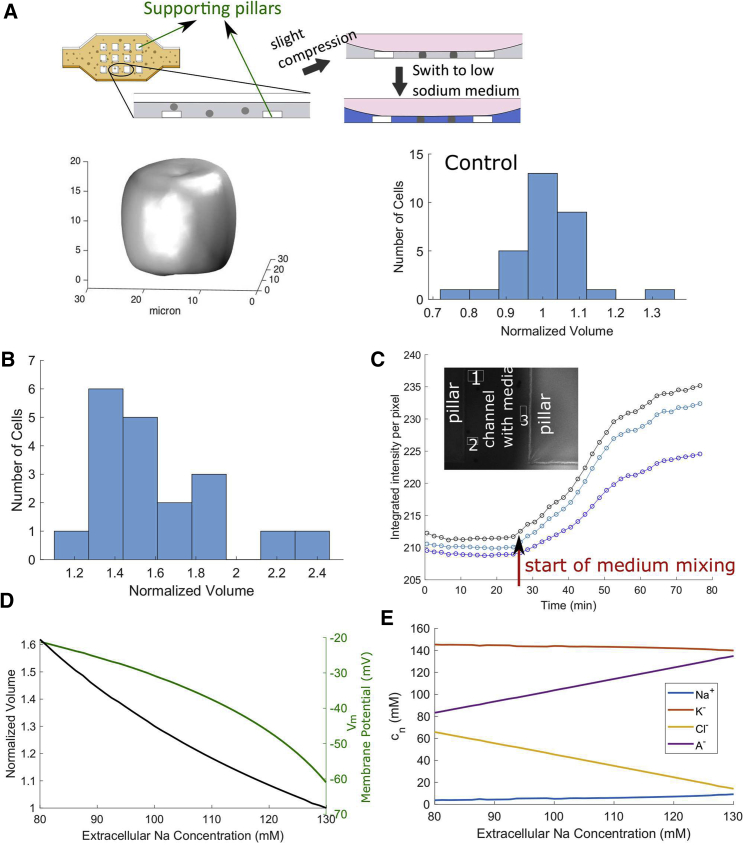

Figure 3.

Cell volume correlates with the extracellular chloride concentration. (A) Cells were suspended using a micropipette, the extracellular medium was changed to low-chloride solution, and the cell volume was simultaneously monitored. The pipette was simply to hold the cell in suspension while measuring its size. (B) The measured cell volume is shown for a single HN31 cell as a function of time during chloride solution switch. The upper panel indicates the time of medium switch; because the low-chloride medium gradually flows into the solution, the exact profile of the chloride concentration is not a perfect step function. In the upper panel we use a step function only to indicate the time of medium switch. (C) Cell volume shows an ∼10% decrease as chloride decreases in the extracellular medium. (Star) Shown here is experimental data, n = 6, mean ± SD = 0.81 ± 0.09, p = 0.0038 according to the Student t-test. (Solid line) Given here is the model prediction. (D) Model prediction of the membrane potential is shown as a function of the extracellular chloride concentration. (E) Model prediction is given on the intracellular ionic contents of the four species as functions of the extracellular chloride concentration. In this model, we let αNKCC = 1.5 × 10−10 mol/m2/s to account for the cellular response to the medium shock with low chloride. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 3 B shows the response of a typical cell to low-chloride medium. Approximately 30 min after switching to the aspartate solution, the cell radius has decreased by ∼10%. The timescale for cell volume adjustment during the chloride/aspartate experiment is roughly three times longer than the timescale for cell volume adjustment during the voltage-clamp experiment. This is likely because the bath solution changes from the high-chloride solution to the high-aspartate solution over a period of ∼15 min, whereas the membrane potential changes almost instantaneously during the voltage-clamp experiment. Fig. 3 C shows the equilibrium volume of cells that are switched into a low-chloride solution after 30 min. Lowering the chloride concentration in the cell environment leads to cell volume shrinkage of 5–10%.

This volume reduction can be predicted by our model (Fig. 3 C). Unlike the voltage-clamp case where the membrane potential and the cell volume is correlated (Fig. 2 B), here with extracellular chloride depletion, the membrane potential is not predicted to vary (Fig. 3 D). The intracellular chloride concentration is predicted to decrease in the low-chloride medium (Fig. 3 E). This is because the chemical potential of chloride in the medium decreases so that chloride is more likely to flow out of the cell. In addition, the model predicts constant intracellular sodium and potassium concentrations when external chloride concentration reduces, indicating an efflux for both, because the cell volume decreased.

Cell volume increases with sodium and potassium exchange in the medium

In addition to chloride, the cell and its medium are rich in sodium and potassium. Under physiological conditions the ratio of intracellular to extracellular concentrations of sodium is <1/10 whereas that of potassium is >10. A perturbation of these ratios may have an effect on cell volume. We therefore exchange the extracellular contents of sodium and potassium by slowly flowing low-sodium/high-potassium medium into a microfluidic device to replace the original Ringer’s solution (Fig. 4 A). A slight compression from the devices keeps the cells in place without overdeforming the spherical cell shape (Fig. 4 A).

Figure 4.

(A) Cells were slightly compressed in the compression microfluidic device and were held in place to avoid being washed away by the medium. The supporting pillars were used to support the compression chamber and to avoid cells being overcompressed. A confocal Z-stack reconstruction of the cell demonstrated that the cells were still close to spheres. We also performed control experiments to measure cell volume fluctuation without environmental perturbation. Volumes of each cell were measured ∼1 h apart. The histogram is shown for n = 31 cells with mean ± SD = 1.014 ± 0.0931. (B) Experimental data shows that the cell volume increases in the low-sodium/high-potassium medium; n = 19, mean ± SD = 1.58 ± 0.33, p = 4.186 × 10−7 according to the Student t-test. (C) New medium with dye was flowed into the device, and different regions of the device were imaged. The dye time-series data for different regions of the device shows that the medium mixing is not uniform. Here we show the dye intensity at three sample nearby locations in the channel. (D) Model prediction of the cell volume and the membrane potential are given as the external sodium is gradually replaced by potassium. (E) Model prediction of the intracellular ionic contents is given as the external sodium is gradually replaced by potassium. In this model, the following parameters are adjusted to account for the cellular response to the medium shock: αATP = 1 m/s, αNa/K,Na = 5, αNa/K,K = 0.01, αNKCC = 1 × 10−13 mol/m2/s. These parameters are mostly involved in the Na/K pump. To see this figure in color, go online.

On average the cell volume increases by ∼60% in the low-sodium/high-potassium medium (Fig. 4 B). Due to the nonuniform mixing rate in the microfluidic device (Fig. 4 C), it is possible that not all cells experience the solution exchange at the same time and to the same degree. It is therefore reasonable to expect that there is a wide variation in cell responses in volume.

This volume increase can again be predicted by our model (Fig. 4 D). Although a depletion of chloride in the medium does not lead to a predicted membrane potential change (Fig. 3 D), our model does predict cell depolarization when cells are exposed to low-sodium/high-potassium medium (Fig. 4 D). This result is consistent with experimental findings that cells become depolarized when surrounded by a high-potassium environment (40). Our model predicts that the intracellular concentrations of sodium and potassium follow slightly with the trends of the corresponding extracellular contents (Fig. 4 E). This can be interpreted from the change of the extracellular chemical potential of the two ionic species. Similar to the model prediction for the voltage clamp (Fig. 2 C), here we also see a predicted large chloride influx upon the cell depolarization (Fig. 4 E).

Cell volume increases with actin depolymerization

To decouple the effects of cytoskeletal forces and osmotic forces on maintaining cell volume, we used 1 μM Lat. A to disrupt the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 5 A). Once again, we used the compression device to hold cells in place while the surrounding medium was replaced. On average, the cell volume increases by ∼6% upon actin depolymerization (Fig. 5 B). Again, because of the nonuniform mixing rate in the microfluidic device, we see a wide range of volume changes across different cells.

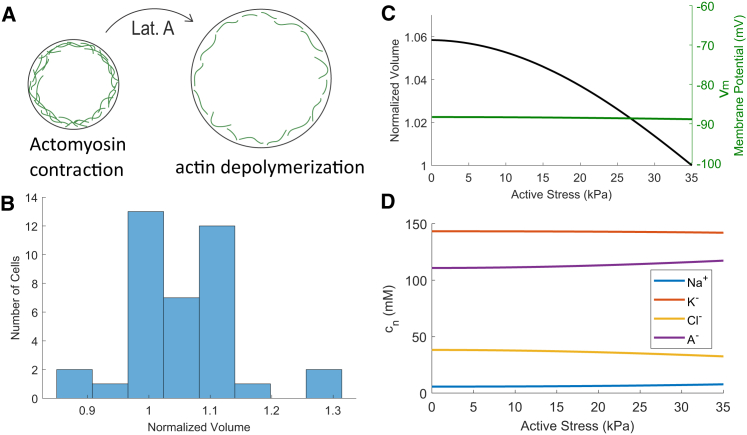

Figure 5.

The role of the actin cortex in maintaining cell volume. (A) Schematics show that depolymerizing actin disrupts the cortex and reduces active contractile stress in the cortex, leading to a cell volume increase (not to scale). (B) Experimental data show that cell volume increases upon actin depolymerization; n = 38, mean ± SD = 1.06 ± 0.087, p = 0.043 according to the Student t-test. The control data is shown in Fig. 4A. (C) Model prediction is given on the cell volume and the membrane potential when Lat. A is added to the cell. (D) Model prediction is given of the concentrations of the intracellular species. In this model we let αATP = 0.25 and let the effective membrane thickness vary linearly from 500 to 10 nm as the contractile stress decreases. To see this figure in color, go online.

In the model, the effect of Lat. A treatment is incorporated by reducing the active cortical stress, . In addition, because actin cortex contributes to the effective membrane thickness, actin depolymerization reduces the thickness of this layer as well. In combination, these lead to a reduced cortical tension, , in the Laplace equation (Eq. 2). Fig. 5 C shows that the cell volume is predicted to increase after actin depolymerization. Because the cortical tension decreases whereas cell volume increases, the right-hand side of Eq. 2 decreases, meaning that the hydrostatic pressure difference across the cell is reduced. At equilibrium where the chemical potential of water is balanced, a reduced intracellular hydrostatic pressure means a reduced intracellular osmotic pressure. We will see in the next section that the relative magnitude of this change is very small, and the intracellular pressure is almost a constant.

Although volume increases, the membrane potential is predicted to be constant (Fig. 5 C). The intracellular ionic variation (Fig. 5 D) is a combined effect of the electro-neutral condition and the balance of the chemical potential of water across the membrane.

Cell volume increases with intracellular ion and protein content

Finally, we present model predictions on the cell volume with varying intracellular content. We are particularly interested in the cytoplasmic protein content (A− in the model) because as cells grow and age, their protein content increases as well. Our model predicts that the cell volume increases almost linearly with the total amount of cell proteins (Fig. 6 A); however, the concentration of the protein, as well as other ion species, remains constant (Fig. 6 B). We can see that the extensive properties of the cell, such as cell volume and protein content, scale linearly with each other, whereas intensive properties, such as ion and protein concentrations and the membrane potential (Fig. 6 A), remain the same. The cell maintains almost constant osmolarity and hydrostatic pressure as it grows for a fixed active cortical tension.

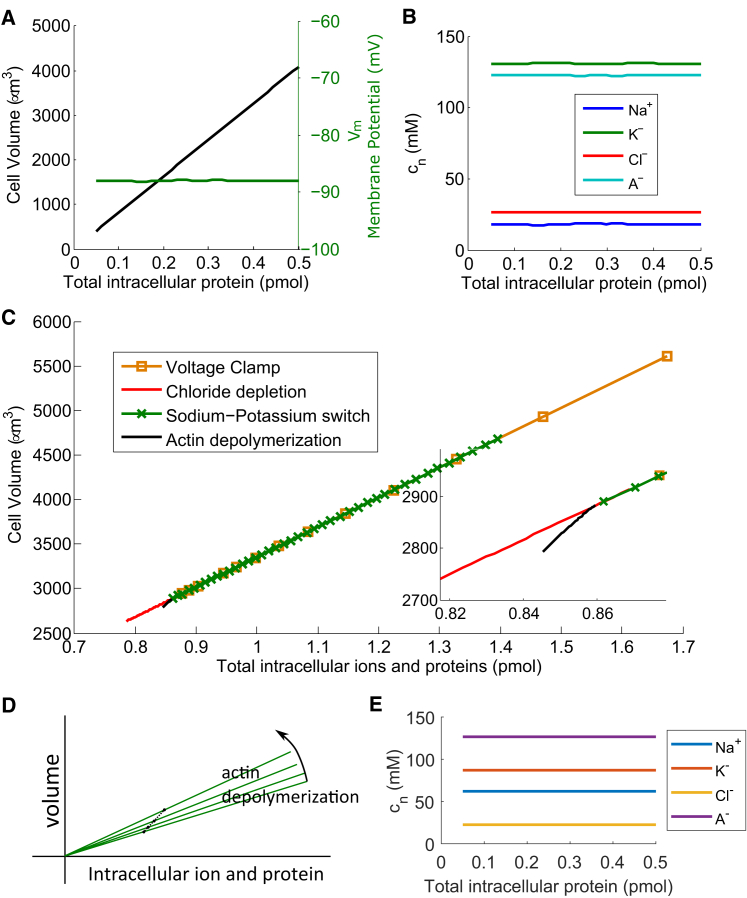

Figure 6.

(A) Model prediction of the cell volume (left axis) and the membrane potential (right axis) are shown as functions of the intracellular protein content. (B) Model prediction is given of the intracellular ion and protein concentrations with the intracellular protein content. (C) Model prediction is shown of the cell volume with the combined total intracellular ion and protein contents from the four experiments: voltage clamp, low-chloride medium, low-sodium/high-potassium medium, and actin depolymerization. (Inset) Given here is a zoom-in for better visualization of the curve for actin depolymerization. (D) Schematic explains the volume-content relation during actin depolymerization (not to scale). Each solid curve represents a generic volume-content relation for a fixed cortical tension, similar to the chloride depletion curve, for example, in (C). A trajectory connecting different points on different solid lines gives the actin depolymerization curve in (C). (E) Model predictions are given of the equilibrium ion concentrations when the flux of Na+/K+ pump is reduced. This panel is a counterpart of (B). Here αATP is 10% of the original value. The model predicts that in this case the cell is unable to maintain a low intracellular sodium concentration and a high intracellular potassium concentration. To see this figure in color, go online.

We can check this idea by examining how cell volume scales with the intracellular ion and protein contents in three situations that have been examined in the experiments: voltage clamp, low-chloride medium, and low-sodium/high-potassium medium. Fig. 6 C shows that the model predicts that the cell volume versus the total cytoplasmic content for these three cases fall on the same line, indicating that the cell volume scales with the total intracellular ion and protein contents. For the case with Lat. A treatment, the cell volume still scales with the total intracellular ion and protein contents but the scaling factor, i.e., the slope, changes slightly. This change can be seen after zoom-in, but the magnitude of the change is small.

The exact slopes in Fig. 6 C can be estimated from the model. Let be the volume of the cell and be the total intracellular ion and protein content. From Eq. 1, at equilibrium, we have

| (17) |

where . Substituting Eq. 2 into Eq. 17, we have

| (18) |

This relationship implies that the total intracellular concentration is only determined by the extracellular concentration, cortical tension, and cell volume. If the cortical tension scales with the radius of the cell, i.e., being a constant, then the internal concentration is a constant, independent of volume. The slope of the volume-content relation can be calculated as

| (19) |

Using order-of-magnitude estimates, is on the order of 300 mM and may vary from 10−3 to 10 mM, much smaller than . Therefore, the slope is roughly constant for fixed external total ionic concentration, leading to the almost linear relation shown in Fig. 6 C. Upon actin depolymerization, the slope will increase slightly as illustrated in Fig. 6 D. A trajectory connecting different points of different cortical tensions gives the actin depolymerization curve in Fig. 6 C.

Conclusions

In this article, using patch-clamp experiments and microfluidic devices we explore how individual HN31 cell volume is correlated with the ionic environment of the cell, the transmembrane potential, and the active stress from the actin cortex. Although the exact results may vary from cell line to cell line, here we focus on a generic response of cells under these conditions. An electrophysiology model is presented to quantitatively explain the cell volume change under these experimental conditions.

We find that changes in the transmembrane electrical potential and ionic environment of the cell can influence cell volume. For example, in the voltage-clamp experiment we see a direct correlation between the cell volume and the membrane potential. Depolarized cells have larger volumes, which was also seen in barnacle muscle cells (41). In the low-sodium/high-potassium medium the membrane potential is predicted to change by at least 50%. This membrane potential change does not always happen in other conditions. For example, in the external chloride depletion and actin depolymerization experiments, the membrane potential is predicted to be unchanged. The relationship between membrane potential and the cell volume is mediated by the ion channels and pumps, i.e., the membrane potential change leads to significant ion fluxes and the cell adjusts its volume by maintaining the same intracellular osmolarity. It is important to note that for all known ion channels and pumps, the fluxes only depend on the intracellular and extracellular ion concentrations and the transmembrane potential (which itself is a function of ion concentrations), and are not a function of the total ionic content. This property leads to homeostatic ion concentration differences at equilibrium and ultimately determines how total ionic and protein content scales with the cell volume.

Voltage clamp is not the only way to perturb the ion fluxes—a change of external ionic environment can also accomplish the same. In this work, we have seen that modified external ionic environment can change the cell volume through changing ion fluxes, but does not always affect the membrane potential. The exact volume change depends on the ion fluxes and thus on ion pump activities. It is possible that for different cell types the volume change can be quantitatively or even qualitatively different. In this model, the cell maintains almost constant intra- to extracellular sodium and potassium concentrations due to the active Na+/K+ pump. It is known that the proper function of the Na+/K+ pump is needed to maintain the relative concentrations of sodium and potassium because the balance of these two species is of physiological importance (42). In the model, we can perturb the pump to investigate its role in maintaining ionic concentrations. Fig. 6 E, as a counterpart of Fig. 6 B, shows the effect of reducing the Na+/K+ pump flux on the intracellular concentrations of sodium and potassium. When the flux through this pump is reduced, the proper level of sodium and potassium is no longer maintained. Further experimental investigations on how Na+/K+ pumps set the homeostatic concentrations of the two species, such as by using fluorescent dyes to label different intracellular ion species, may provide more insights into this.

The model predicts significant change of the membrane potential when cells are in the low-sodium/high-potassium medium (Fig. 4 D), in contrast to the constant membrane potential in low-chloride medium (Fig. 3 D). This difference comes from the predicted nontrivial change of intra- to extracellular chloride concentration ratio in the low-sodium/high-potassium medium (Fig. 4 E). Under equilibrium, the total ion flux of each species is zero, i.e., Eqs. 5, 6, and 7 vanish. We can rearrange the three equations to eliminate JNa/K and JNKCC, obtaining

| (20) |

Substituting Eq. 8 into Eq. 20, we obtain an expression for the membrane potential

| (21) |

which can be regarded as a revised Goldman-Hodgkin-Kate equation (25) when the Na+/K+ pump and the NKCC are considered. In the low-chloride medium case, and remain the same (Fig. 3 E), and is also close to a constant because the intracellular chloride concentration decreases with extracellular chloride concentration (Fig. 3 E). The membrane potential in Eq. 21 therefore remains constant. In the low-sodium/high-potassium medium case, the intracellular sodium and potassium concentrations vary with external concentrations (Fig. 4 E) so that and do not change significantly. However, the intracellular concentration of chloride increases by several folds upon medium switch (Fig. 4 E), leading to a large decrease in , which in turn depolarizes the cell, as seen in Fig. 4 D. This effect is mainly due to the presence of the NKCC, and this prediction can be checked in experiments with sufficiently precise single-cell voltage measurements.

Although active pumps regulate the intracellular ionic concentrations of each species and sometimes the membrane potential as well, the model actually predicts that they have no influence on the cell volume overall. For example, in the model we can remove the Na+/K+ pump and the NKCC and retain the relation seen in Fig. 6 C. This does not mean that active pumps do not play a role; rather, their role is mainly to regulate each in a way that does not change significantly (Eq. 18). This result is a restatement of the volume-content relation (Fig. 6 C) that the intracellular protein content is the leading contributor to the cell volume. Note that changes in would change functions of biologically important proteins such as the ribosome (42), and therefore the ion pumps are important in maintaining the proper chemical environment in which the cell can function.

Actin dynamics and cortical contractile stress can also affect cell volume through multiple mechanisms such as vesicle transport and tension-activated channels (30, 43). In this article we find that the actin cortex, on average, had a small effect on HN31 cell volume. The model predicts the same mainly because we do not include a strong coupling between the actin cortex and the rest of the system, except in the Laplace equation and the tension-gated passive ion channels. Depending on the cell type, the stress in the actin network and the membrane potential can be coupled (44), or the stress in the membrane can change the membrane capacitance (45). In general, there would be some cross talk among actomyosin dynamics, membrane tension, ion channel distribution, and activation of ion channels that further connects actin structure and cell volume. The full picture of cell volume regulation on short timescales awaits clear experimental and theoretical elucidation.

Author Contributions

F.Y., D.Y., and S.X.S. designed the experiments. F.Y., V.K.A.S., and M.B.J. performed the experiments. Y.L. and S.X.S. designed the model and performed the model calculations. B.F. supplied the cell line.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01GM114675 and U54CA210172.

Editor: Vivek Shenoy.

Footnotes

David Yue, deceased December 23, 2014.

References

- 1.Bennett M.R., Pang W.L., Hasty J. Metabolic gene regulation in a dynamically changing environment. Nature. 2008;454:1119–1122. doi: 10.1038/nature07211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.López-Maury L., Marguerat S., Bähler J. Tuning gene expression to changing environments: from rapid responses to evolutionary adaptation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:583–593. doi: 10.1038/nrg2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks A.N., Turkarslan S., Baliga N.S. Adaptation of cells to new environments. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2011;3:544–561. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd A.C. The regulation of cell size. Cell. 2013;154:1194–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wärntges S., Gröne H.J., Lang F. Cell volume regulatory mechanisms in progression of renal disease. J. Nephrol. 2001;14:319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X., Xu T. Molecular mechanism of size control in development and human diseases. Cell Res. 2011;21:715–729. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonzalez S., Rallis C. The tor signaling pathway in spatial and temporal control of cell size and growth. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017;5:61. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2017.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lang F., Ritter M., Gulbins E. Cell volume in the regulation of cell proliferation and apoptotic cell death. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2000;10:417–428. doi: 10.1159/000016367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakab M., Ritter M. Mechanisms and Significance of Cell Volume Regulation. Vol 152. Karger; Basel, Switzerland: 2006. Cell volume regulatory ion transport in the regulation of cell migration; pp. 161–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang F. Mechanisms and significance of cell volume regulation. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007;26(Suppl 5):613S–623S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tao J., Li Y., Sun S.X. Cell mechanics: a dialogue. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2017;80:036601. doi: 10.1088/1361-6633/aa5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart M.P., Helenius J., Hyman A.A. Hydrostatic pressure and the actomyosin cortex drive mitotic cell rounding. Nature. 2011;469:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature09642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pedersen S.F., Hoffmann E.K. Possible interrelationship between changes in F-actin and myosin II, protein phosphorylation, and cell volume regulation in Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2002;277:57–73. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson J., Körber F., Lambert S. Application of moderate hydrostatic pressure induces unit-cell changes in rhombohedral insulin. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1996;52:1012–1015. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996004386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang H., Sun S.X. Cellular pressure and volume regulation and implications for cell mechanics. Biophys. J. 2013;105:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackiston D.J., McLaughlin K.A., Levin M. Bioelectric controls of cell proliferation: ion channels, membrane voltage and the cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3527–3536. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chernet B.T., Levin M. Transmembrane voltage potential is an essential cellular parameter for the detection and control of tumor development in a Xenopus model. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013;6:595–607. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hui T.H., Kwan K.W., Lin Y. Regulating the membrane transport activity and death of cells via electroosmotic manipulation. Biophys. J. 2016;110:2769–2778. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salbreux G., Joanny J.F., Pullarkat P. Shape oscillations of non-adhering fibroblast cells. Phys. Biol. 2007;4:268–284. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/4/4/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter G.L., Crawford J.M., Kiehart D.P. Ion channels contribute to the regulation of cell sheet forces during Drosophila dorsal closure. Development. 2014;141:325–334. doi: 10.1242/dev.097097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmann E.K., Holm N.B., Lambert I.H. Functions of volume-sensitive and calcium-activated chloride channels. IUBMB Life. 2014;66:257–267. doi: 10.1002/iub.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu Z., Dubin A.E., Patapoutian A. SWELL1, a plasma membrane protein, is an essential component of volume-regulated anion channel. Cell. 2014;157:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sardini A., Amey J.S., Higgins C.F. Cell volume regulation and swelling-activated chloride channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1618:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halliwell J.V., Plant T.D., Standen N.B. Voltage clamp techniques. In: Standen N.B., Gray P.T.A., Whitaker M.J., editors. Microelectrode Technique. The Plymouth Workshop Handbook. The Company of Biologists; Cambridge, UK: 1987. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ermentrout G.B., Terman D.H. Springer; New York: 2010. Mathematical Foundations of Neuroscience. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douglas W.W., Kanno T., Sampson S.R. Influence of the ionic environment on the membrane potential of adrenal chromaffin cells and on the depolarizing effect of acetylcholine. J. Physiol. 1967;191:107–121. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Si F., Li B., Sun S.X. Bacterial growth and form under mechanical compression. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11367. doi: 10.1038/srep11367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romani A.M. Cellular magnesium homeostasis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2011;512:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tao J., Sun S.X. Active biochemical regulation of cell volume and a simple model of cell tension response. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1541–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He L., Tao J., Sun S.X. Role of membrane-tension gated Ca flux in cell mechanosensation. J. Cell Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1242/jcs.208470. Published online February 22, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veksler A., Gov N.S. Calcium-actin waves and oscillations of cellular membranes. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1558–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Y., Mori Y., Sun S.X. Flow-driven cell migration under external electric fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015;115:268101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.268101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell J.M. Sodium-potassium-chloride cotransport. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:211–276. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett M.R., Farnell L., Gibson W.G. A quantitative model of cortical spreading depression due to purinergic and gap-junction transmission in astrocyte networks. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5648–5660. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.137190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadsby D.C., Kimura J., Noma A. Voltage dependence of Na/K pump current in isolated heart cells. Nature. 1985;315:63–65. doi: 10.1038/315063a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao J., Mathias R.T., Baldo G.J. Two functionally different Na/K pumps in cardiac ventricular myocytes. J. Gen. Physiol. 1995;106:995–1030. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.5.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bueno-Orovio A., Sánchez C., Rodriguez B. Na/K pump regulation of cardiac repolarization: insights from a systems biology approach. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:183–193. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong C.M. The Na/K pump, Cl ion, and osmotic stabilization of cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:6257–6262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931278100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lodish H., Berk A., Darnell J. William H. Freeman; New York: 2004. Molecular Cell Biology. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zierler K., Rogus E.M., Wu F.S. Insulin action on membrane potential and glucose uptake: effects of high potassium. Am. J. Physiol. 1985;249:E17–E25. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1985.249.1.E17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berman D.M., Peña-Rasgado C., Rasgado-Flores H. Changes in membrane potential associated with cell swelling and regulatory volume decrease in barnacle muscle cells. J. Exp. Zool. 1994;268:97–103. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402680205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mulkidjanian A.Y., Bychkov A.Y., Koonin E.V. Origin of first cells at terrestrial, anoxic geothermal fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E821–E830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117774109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pedersen S.F., Hoffmann E.K., Mills J.W. The cytoskeleton and cell volume regulation. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2001;130:385–399. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00429-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Callies C., Fels J., Oberleithner H. Membrane potential depolarization decreases the stiffness of vascular endothelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:1936–1942. doi: 10.1242/jcs.084657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwasa K.H. Effect of stress on the membrane capacitance of the auditory outer hair cell. Biophys. J. 1993;65:492–498. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81053-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stroka K.M., Jiang H., Konstantopoulos K. Water permeation drives tumor cell migration in confined microenvironments. Cell. 2014;157:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]