Abstract

Objectives

Secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure is associated with cardiovascular disease. This study aims to determine the association between SHS exposure estimated by questionnaire and hypertension in Korean never smokers.

Setting

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) V was conducted from 2010 to 2012.

Participants

We selected the never smokers aged over 20 years who answered the question about the SHS exposure.

Primary and secondary measures

SHS exposure in both the home and work place was estimated using a self-reporting questionnaire. We investigated the association between SHS exposure and hypertension by using multivariate analysis. And we evaluated the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure values according to SHS exposure after adjusting for possible confounding factors. All analyses were stratified by women and men.

Results

There were 10 532 (women 8987 and men 1545) never smokers. We divided the subjects into three groups according to the amount of SHS exposure: none—group I, <2 hour/day—group II and ≥2 hour/day—group III. Using multivariate analysis, hypertension was more commonly associated with group III than group I in women (adjusted OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.04, p=0.011). Adjusted mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure values in women who were not taking antihypertensive medication were significantly elevated in group III by 2.3 and 1.7 mm Hg, respectively.

Conclusion

SHS exposure is significantly associated with hypertension in women never smokers.

Keywords: second-hand smoke, hypertension, blood pressure, knhanes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study demonstrated that hypertension is more common in women never smokers with higher daily secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure and measured the differences between systolic and diastolic blood pressure means by different SHS exposure groups.

This study included the largest population (10 532) used to examine SHS exposure based on a well-structured nationwide survey.

Survey design analysis was applied to reduce the possibility of biased estimates.

This cross-sectional analysis could not conclude a causal relationship between SHS exposure and hypertension.

Introduction

With a global prevalence of 26.4%,1 hypertension is a large contributor to the burden of disease in adults. Well-known risk factor of hypertension is family history, but it is non-modifiable. Active cigarette smoking is another risk factor,2 and it is totally preventable.3

Active smoking causes detrimental effects on smokers themselves, but secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure can also harm innocent bystanders. About 85% of SHS exposure results from sidestream smoke, which rises from the tip of a burning cigarette.4 Sidestream smoke is potentially more harmful because it is not filtered. In recent years, the public has paid more attention to the harmful effect of SHS exposure on cardiovascular diseases5 and supportive evidence is accumulating.6–8 Although the positive relationship between SHS exposure and hypertension has been reported, some studies did not confirm this relationship.9 In Korea, the adult smoking rate was 24.1% in 2013, and there was a big difference between sexes, 42.1% in men and 6.2% in women. In terms of the prevalence, women are more vulnerable to SHS exposure. The aim of this study was to elucidate the association between SHS exposure and hypertension in Korean never smokers using national survey data.

Materials and methods

Study population

The detailed data obtained from the fifth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) V 2010–2012 are described elsewhere.10 KNHANES is an annual collection of data from the Korean Statistical Office census of 3800 households from 576 randomly selected survey areas with the number selected from each area proportional to its size. Trained interviewers administer questionnaires on various health-related information, and subjects self-report their alcohol and smoking habits. KNHANES uses a complex, multistage probability sample design. The sample represents the total non-institutionalised civilian population of Korea. These data are available on the internet (https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr). Adult never smokers >20 years old with secondhand smoking history available were included. Never smoker was defined when the total amount of smoking was <100 cigarettes during the lifetime. If histories of smoking or SHS exposure were not available, the cases were excluded. The institutional review board of Seoul National University Hospital waived the need for written informed consent from the participants (IRB no: H1509-011-699).

Definition of SHS exposure

Daily SHS exposure time was estimated both in the workplace and home. Total SHS exposure was calculated by the summation of both values. The total amount of SHS exposure was categorised into three groups according to exposure time; none (group I), <2 hour/day (group II) and ≥2 hour/day (group III).

Definition of hypertension

Hypertension was defined if one or more of the criteria below were met. (1) Diagnosed by physician, (2) using antihypertensive medications, (3) systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥140 mm Hg and (4) diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg. The measurement of BP has been described elsewhere.11 In brief, after at least 5 min rest in a sitting position, BP was manually measured 3 times at 30 s intervals. Finally, the average of the second and third measurements were used.

Statistical analysis

Weighted analysis was used for the KNHANES V data. Χ2 test was used for categorical variables and t-test was used for continuous variables in univariate analysis.12 Multivariable logistic regression with survey weight analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between SHS exposure and hypertension. In model 1, the only covariable was age, while in model 2, multiple covariates such as age, height, weight, waist circumference, serum triglyceride, fasting glucose, education, occupation, alcohol intake and marital status were included and adjusted for. In addition, we compared SBP and DBP means between groups, again adjusting for covariates. This analysis was limited to participants who were not taking antihypertensive medications. P value <0.05 was considered significant. We used the STATA software V.13.1 for statistical analysis.

Patient and public involvement

The KNHANES V data were released after anonymisation. The study population were not involved in the design of this study.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants

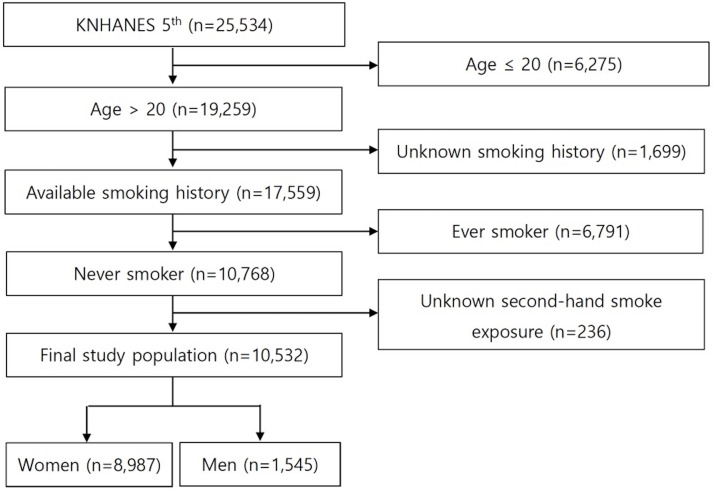

The KNHANES V data include 25 534 participants. Among them, we found 19 259 adults (age >20 years old). After excluding 1699 participants with unknown smoking history, 6791 ever smokers and 236 with unknown SHS exposure, a total of 10 532 (women 8987 and men 1,545) never smokers were available for analysis (figure 1). Their mean age was 47.7±0.3 years in women and 39.9±0.5 years in men. The majority of the study population was light drinkers (<1/week), and socioeconomic status was evenly distributed by SHS exposure groups (table 1). The percentages of participants categorised into group I, II and III according to the degree of their SHS exposures were 68.1%, 24.2%, 7.7% in women and 53.3%, 39.4%, 7.2% in men. The participants in group I were older than those in the two other groups. The percentages of hypertension in group I, II and III were 29.3%, 19.3%, 25.9% in women and 25.2%, 22.0%, 30.6% in men. BP, education level, alcohol intake were significantly different between the three SHS exposure groups.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study population. KNHANES, Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to the degree of secondhand smoke exposure.

| Variables | Women | P values | Men | P values | ||||

| Secondhand smoke exposure | Secondhand smoke exposure | |||||||

| None | <2 hour/day | ≥2 hour/day | None | <2 hour/day | ≥2 hour/day | |||

| % of total | 68.1 | 24.2 | 7.7 | 53.3 | 39.4 | 7.2 | ||

| Age (years) | 49.6±0.3 | 42.9±0.4 | 45.2±0.6 | <0.001* | 41.7±0.7 | 37.4±0.6 | 40.2±1.4 | <0.001* |

| Weight (kg) | 57.5±0.2 | 57.5±0.3 | 59.2±0.5 | <0.001* | 70.1±0.5 | 71.4±0.6 | 72.7±1.4 | 0.032* |

| Height (cm) | 156.6±0.1 | 157.9±0.2 | 157.8±0.3 | <0.001* | 171.4±0.3 | 172.2±0.3 | 170.6±0.8 | 0.783 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 78.7±0.2 | 76.9±0.3 | 78.9±0.5 | 0.009* | 82.9±0.4 | 83.0±0.5 | 84.8±1.1 | 0.231 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.5±0.1 | 23.1±0.1 | 23.8±0.2 | 0.536 | 23.8±0.1 | 24.1±0.2 | 24.9±0.4 | 0.021* |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | ||||||||

| Systole | 117.5±0.3 | 113.5±0.5 | 117.7±0.9 | <0.001* | 119.3±0.6 | 118.9±0.6 | 120.8±1.7 | 0.740 |

| Diastole | 74.0±0.2 | 73.6±0.3 | 75.7±0.5 | 0.082 | 77.9±0.4 | 79.9±0.5 | 79.9±1.1 | 0.005* |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190.4±0.7 | 186.5±1.0 | 192.9±1.8 | 0.453 | 183.±1.6 | 182.7±1.8 | 186.5±3.8 | 0.666 |

| High density lipoprotein (mg/dL) | 55.2±0.3 | 55.6±0.6 | 57.7±1.1 | 0.068 | 51.0±0.9 | 50.3±1.2 | 50.4±2.5 | 0.583 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 115.0±1.8 | 104.7±1.9 | 112.2±4.4 | 0.016* | 121.8±3.5 | 129.6±4.7 | 121.4±7.2 | 0.339 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 95.9±0.4 | 93.6±0.5 | 95.1±0.9 | 0.008* | 96.6±0.9 | 95.7±0.8 | 96.6±1.8 | 0.658 |

| Hypertension | 29.3 | 19.3 | 25.9 | <0.001* | 25.2 | 22.0 | 30.6 | 0.197 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 14.8 | 9.8 | 10.0 | <0.001* | 10.0 | 9.2 | 13.1 | 0.527 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 25.6 | 17.0 | 18.8 | <0.001* | 23.2 | 20.2 | 12.9 | 0.325 |

| Alcohol intake | ||||||||

| Never drinker | 21.7 | 11.2 | 18.5 | <0.001 * | 11.3 | 7.3 | 7.4 | <0.001* |

| Former drinker | 18.0 | 13.9 | 16.5 | 13.5 | 6.1 | 5.9 | ||

| Light drinker (≤1/week) | 53.9 | 66.8 | 57.3 | 56.7 | 66.5 | 53.8 | ||

| Moderate drinker (2–3/week) | 5.1 | 7.1 | 6.2 | 13.9 | 16.5 | 22.4 | ||

| Heavy drinker (≥4/week) | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 10.5 | ||

| Marital status | 88.8 | 76.9 | 84.1 | <0.001* | 58.0 | 59.0 | 59.0 | 0.955 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Below middle school | 30.4 | 18.2 | 26.8 | <0.001* | 9.9 | 2.9 | 7.7 | <0.001* |

| Middle school | 9.8 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 9.0 | ||

| High school | 29.8 | 39.9 | 33.1 | 43.0 | 40.3 | 47.6 | ||

| Above high school | 30.1 | 31.9 | 30.0 | 40.9 | 50.5 | 35.8 | ||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||

| 1Q | 25.3 | 25.3 | 27.3 | 0.144 | 30.2 | 21.8 | 30.5 | 0.116 |

| 2Q | 26.8 | 25.7 | 21.2 | 21.2 | 24.4 | 20.0 | ||

| 3Q | 25.3 | 25.9 | 23.7 | 25.6 | 25.5 | 26.8 | ||

| 4Q | 22.6 | 23.1 | 27.9 | 23.0 | 28.3 | 22.7 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||

| Manager or professional | 11.0 | 15.6 | 11.8 | <0.001* | 21.8 | 28.6 | 12.5 | <0.001* |

| Office worker | 5.0 | 14.3 | 13.3 | 7.6 | 15.5 | 15.6 | ||

| Service | 9.0 | 22.3 | 42.4 | 7.1 | 15.0 | 13.8 | ||

| Farmer worker or fisherman | 6.0 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 1.3 | ||

| Technician | 2.3 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 9.1 | 21.5 | 39.5 | ||

| Labour worker | 8.0 | 12.8 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 9.2 | ||

| Unemployed (outside house) | 58.8 | 24.7 | 17.4 | 41.6 | 7.6 | 8.2 | ||

The data were presented as mean±SE in continuous variables and % in categorical variables.

**P<0.05.

Hypertension is associated with SHS exposure measured by questionnaire in women never smokers

In women, hypertension was significantly associated with SHS exposure (group III) after adjustment for age (model 1, adjusted OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.93, p=0.003) and even after adjustment for age, height, weight, waist circumference, serum triglyceride, fasting glucose, education, occupation, alcohol intake and marital status (model 2, adjusted OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.04, p=0.011, table 2). But in men, no statistically significant differences were seen.

Table 2.

Association between secondhand smoke (SHS) exposure and hypertension.

| For hypertension | Women | Men | ||||||||||

| Model 1* | Model 2† | Model 1* | Model 2† | |||||||||

| Adjusted OR |

95% CI | P values | Adjusted OR |

95% CI | P values | Adjusted OR |

95% CI | P values | Adjusted OR |

95% CI | P values | |

| SHS exposure | ||||||||||||

| None | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| <2 hour/day | 1.06 | 0.90 to 1.25 | 0.487 | 1.01 | 0.91 to 1.33 | 0.314 | 1.07 | 0.78 to 1.47 | 0.664 | 0.87 | 0.60 to 1.25 | 0.435 |

| ≥2 hour/day | 1.49 | 1.14 to 1.93 | 0.003** | 1.50 | 1.10 to 2.04 | 0.011‡ | 1.52 | 0.89 to 2.61 | 0.128 | 0.93 | 0.52 to 1.68 | 0.818 |

*Adjusted for age.

†Adjusted for age, height, weight, waist circumference, serum triglyceride, fasting glucose, education, occupation, alcohol intake and marital status.

*P<0.05; **P<0.01.

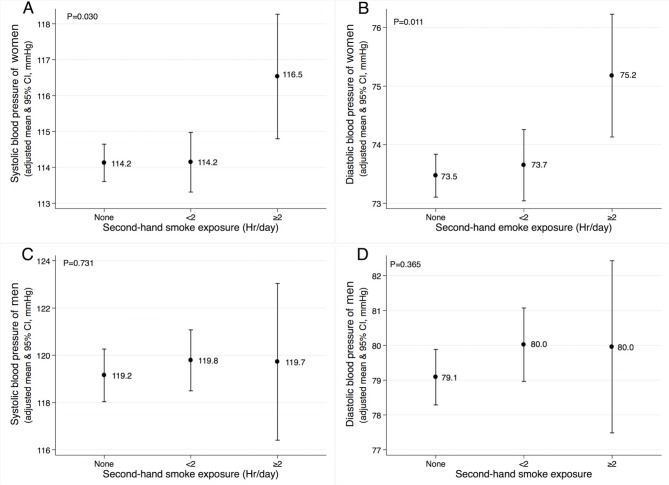

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure is increasing according to SHS exposure

The mean systolic and diastolic BP increased proportional to the increasing SHS exposure in women. On average, the differences between group III and group I were 2.3 mm Hg and 1.7 mm Hg in systolic and diastolic BP, respectively (p=0.030 and p=0.011) (figure 2). In men, we observed a tendency towards higher mean systolic and diastolic BP values in groups II and III compared with group I.

Figure 2.

Adjusted means of systolic and diastolic blood pressure according to secondhand smoke exposure in women (A and B) and men (C and D) population without antihypertensive treatment. The mean values are adjusted for age, height, weight, waist circumference, serum triglyceride, fasting glucose, education, occupation, alcohol intake and marital status.

Discussion

This study demonstrated the association between SHS exposure measured by self-reported questionnaire in women never smokers and hypertension, using a well-designed nationwide survey.13 Our findings strengthen the evidence of the harmful effect of chronic SHS exposure on hypertension. Additionally, we calculated the difference in mean systolic and diastolic BP between women group I and III by 2.3 and 1.7 mm Hg, respectively. According to a previous study, a 3 mm Hg systolic BP difference was observed with a 10 kg increase in body weight.14Compared with this 3 mm Hg systolic BP change accomplished by weight reduction, the value of 2.3 mm Hg associated with SHS exposure is significant.

The association between hypertension and SHS exposure was observed only in women. We postulate three possibilities. First, men never smokers were younger than women who never smoked (39.9±0.5 vs 47.7±0.3). The influence of SHS exposure on BP could be limited in younger man.15 Second, SHS exposure could influence cardiovascular disease due to sex-dependent biologic effect.16 Third, there could be some limitations of statistical model 2 for men because of the many co-variables and the small numbers involved. The low statistical power due to small sample size could affect results. In our dataset, the proportion of men never smokers was only 19.4% of total men population aged over 20 years. Although we did not achieve statistically significant results in men, the changing pattern of systolic and diastolic BP was the same and it could support the biological effect between SHS exposure and BP.

Pharmacologically, nicotine stimulates the sympathetic nervous system in active smokers.17 18 Epinephrine and norepinephrine are released by nicotine stimulation, and these catecholamines increase myocardial contractility and promote vasoconstriction, which results in increases in BP.19 The association between smoking and hypertension has also been observed in a mouse model,20 and in epidemiological studies.2 Moreover, the amount of smoking was positively correlated with hypertension21 and carotid artery atherosclerosis severity.22 The biological effect of SHS exposure on BP could be extrapolated from the effects of active smoking. Serum nicotine level was increased after SHS exposure in healthy non-smokers.23 In the context of active smoking exposure, the duration or amount of SHS exposure is also important in the evaluation of the chronic effect of passive smoking. Although the experimental studies of short-term SHS exposure did not demonstrate a change in BP,23 24 population-based studies have shown that the habitual SHS exposure is associated with hypertension.6 7

Theoretically, SHS exposure can be determined by direct measurements of smoke components in the air, self-reported questionnaires, or by measurements of biomarkers from body fluid, such as serum, urine or saliva.25 The correlation between self-reported questionnaire and biochemical assessment has been generally accurate in prior meta-analysis.26 The association between hypertension and SHS exposure was demonstrated by using serum cotinine in the previous study6 and self-reported questionnaire in our study. Compared with biomarkers, self-reported questionnaires are inexpensive and provide information on long-term exposure.

To our knowledge, this study included the largest population used to examine SHS exposure based on a well-structured nationwide survey (KNHANES V),13 and a survey design analysis was applied to reduce the possibility of biased estimates.12 In addition, we included various potential confounding factors, including age, height, weight, waist circumference, serum triglyceride, fasting glucose, education, occupation, alcohol intake and marital status in the statistical model to clarify the conclusion. However there were some limitations. First, our cross-sectional analysis could not conclude a causal relationship between SHS exposure and hypertension. For example, in some cases, hypertension may have been present before exposure to SHS. Second, information on the smoke concentration and the environment where SHS exposure occurred was not available. Third, we could not exclude hidden smokers. The proportion of cotinine-verified active smokers was previously noted to be larger than that of self-reported smokers.27 In our data set (KNHANES V), urine cotinine level was available in 19% of women never smokers. In that group, 2.7% women never smokers had a urine cotinine level >200 ng/mL, the cut-off value defining an active smoker.25 Thus, the possibility of active smoker contamination does exist. Forth, there could be concerns that factors related to hypertension were not sufficiently investigated. For example, oestrogen increases the susceptibility to hypertension.28 Because oestrogen tends to rise in perimenopausal period, perimenopausal women hence are likely to become hypertensive. Although our survey did not measure the oestrogen level, the analysis in which perimenopausal participants were excluded also shows the significant relationship between SHS exposure and hypertension (data not shown). A family history of hypertension could also contribute to the development of hypertension. We did not exclude participants who had a family history of hypertension. However, even when participants with a self-reported family history of hypertension were excluded, the significant relationship between SHS exposure and hypertension was also observed (data not shown).

In conclusion, on using self-reported questionnaires, we found that SHS exposure was significantly associated with hypertension in Korean women never smokers. Both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were significantly elevated in the SHS exposed population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YSP and C-HL contributed to the conceptualisation. YSP, C-HL and Y-IL were responsible for the data curation. YSP, C-HL and K-HY were responsible for the methodology. C-HL was involved in the project administration. YSP and C-HL drafted the original manuscript. All authors contributed to the review and editing.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Seoul National University Hospital IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The original data came from Korean National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/knhanes/eng/index.do). All the data presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author at kauri670@empal.com.

References

- 1. Bromfield S, Muntner P. High blood pressure: the leading global burden of disease risk factor and the need for worldwide prevention programs. Curr Hypertens Rep 2013;15:134–6. 10.1007/s11906-013-0340-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowman TS, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, et al. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and risk of incident hypertension in women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:2085–92. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization, World Heart Federation, World Stroke Organization. Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/atlas_cvd/en/ (accessed 27 Nov 2017).

- 4. Centers for Disease Control (CDC). 1986 Surgeon General’s report: the health consequences of involuntary smoking. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1986;35:769–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jacobs M, Alonso AM, Sherin KM, et al. Policies to restrict secondhand smoke exposure: American College of Preventive Medicine Position Statement. Am J Prev Med 2013;45:360–7. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alshaarawy O, Xiao J, Shankar A. Association of serum cotinine levels and hypertension in never smokers. Hypertension 2013;61:304–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.198218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Makris TK, Thomopoulos C, Papadopoulos DP, et al. Association of passive smoking with masked hypertension in clinically normotensive nonsmokers. Am J Hypertens 2009;22:853–9. 10.1038/ajh.2009.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li N, Li Z, Chen S, et al. Effects of passive smoking on hypertension in rural Chinese nonsmoking women. J Hypertens 2015;33:2210–4. 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie B, Palmer PH, Pang Z, et al. Environmental tobacco use and indicators of metabolic syndrome in Chinese adults. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:198–206. 10.1093/ntr/ntp194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kweon S, Kim Y, Jang MJ, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:69–77. 10.1093/ije/dyt228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee HT, Shin J, Min SY, et al. The relationship between bone mineral density and blood pressure in the Korean elderly population: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2008-2011. Clin Exp Hypertens 2015;37:212–7. 10.3109/10641963.2014.933971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim Y, Park S, Kim NS, et al. Inappropriate survey design analysis of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey may produce biased results. J Prev Med Public Health 2013;46:96–104. 10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.2.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim Y. The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES): current status and challenges. Epidemiol Health 2014;36:e2014002 10.4178/epih/e2014002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation 2006;113:898–918. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Primatesta P, Falaschetti E, Gupta S, et al. Association between smoking and blood pressure: evidence from the health survey for England. Hypertension 2001;37:187–93. 10.1161/01.HYP.37.2.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang M, An Q, Yeh F, et al. Smoking-attributable mortality in American Indians: findings from the Strong Heart Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:553–61. 10.1007/s10654-015-0031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grassi G, Seravalle G, Calhoun DA, et al. Mechanisms responsible for sympathetic activation by cigarette smoking in humans. Circulation 1994;90:248–53. 10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Karakaya O, Barutcu I, Kaya D, et al. Acute effect of cigarette smoking on heart rate variability. Angiology 2007;58:620–4. 10.1177/0003319706294555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2003;46:91–111. 10.1016/S0033-0620(03)00087-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Talukder MA, Johnson WM, Varadharaj S, et al. Chronic cigarette smoking causes hypertension, increased oxidative stress, impaired NO bioavailability, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac remodeling in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;300:H388–H396. 10.1152/ajpheart.00868.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thuy AB, Blizzard L, Schmidt MD, et al. The association between smoking and hypertension in a population-based sample of Vietnamese men. J Hypertens 2010;28:245–50. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833310e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tell GS, Polak JF, Ward BJ, et al. Relation of smoking with carotid artery wall thickness and stenosis in older adults. The Cardiovascular Health Study. The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Collaborative Research Group. Circulation 1994;90:2905–8. 10.1161/01.CIR.90.6.2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Argacha JF, Adamopoulos D, Gujic M, et al. Acute effects of passive smoking on peripheral vascular function. Hypertension 2008;51:1506–11. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.104059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hausberg M, Mark AL, Winniford MD, et al. Sympathetic and vascular effects of short-term passive smoke exposure in healthy nonsmokers. Circulation 1997;96:282–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Florescu A, Ferrence R, Einarson T, et al. Methods for quantification of exposure to cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke: focus on developmental toxicology. Ther Drug Monit 2009;31:14–30. 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181957a3b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, et al. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1086–93. 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jung-Choi KH, Khang YH, Cho HJ. Hidden female smokers in Asia: a comparison of self-reported with cotinine-verified smoking prevalence rates in representative national data from an Asian population. Tob Control 2012;21:536–42. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Subramanian M, Balasubramanian P, Garver H, et al. Chronic estradiol-17β exposure increases superoxide production in the rostral ventrolateral medulla and causes hypertension: reversal by resveratrol. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011;300:R1560–R1568. 10.1152/ajpregu.00020.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.