Abstract

Objectives

Little is known about the effectiveness of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) for elderly patients who had out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). The aim of this study was to examine the impact of age on outcomes among patients who had OHCA treated with ECPR.

Design

Single-centre retrospective cohort study.

Setting

A critical care centre that covers a population of approximately 1 million residents.

Participants

Patients who had consecutive OHCA aged ≥18 years who underwent ECPR from 2005 to 2013.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary outcomes were 1 month neurologically favourable outcomes and survival. To determine the association between advanced age and each outcome, we fitted multivariable logistic regression models using: (1) age as a continuous variable and (2) age as a categorical variable (<50 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years and ≥70 years).

Results

Overall, 144 patients who had OHCA who underwent ECPR were eligible for our analyses. The proportion of neurologically favourable outcomes was 7%, while survival was 19% in patients who had OHCA. After the adjustment for potential confounders, while advanced age was non-significantly associated with neurologically favourable outcomes (adjusted OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.01), p=0.08), the association between advanced age and the poor survival rate was significant (adjusted OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.93 to 0.99), p=0.04). Additionally, compared with age <50 years, age ≥70 years was non-significantly associated with poor neurological outcomes (adjusted OR 0.08 (95% CI 0.01 to 1.00), p=0.051), whereas age ≥70 years was significantly associated with worse survival in the adjusted model (adjusted OR 0.14 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.80), p=0.03).

Conclusions

In our analysis of consecutive OHCA data from a critical care hospital in an urban area of Japan, we found that advanced age was associated with the lower rate of 1-month survival in patients who had OHCA who underwent ECPR. Although larger studies are required to confirm these results, our findings suggest that ECPR may not be beneficial for patients who had OHCA aged ≥70 years.

Keywords: resuscitation, emergency medicine, cardiac arrest, elderly, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first study investigating the impact of age on outcomes among patients who had out-of-hospital cardiac arrest treated with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation, including patients aged ≥75 years.

There are consistent findings in both multivariable models using age as continuous variable and as a categorical variable.

Our sample consisted of retrospective data from a single centre in Japan with a limited sample size; thereby, our inferences might not be generalisable to other healthcare settings.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major, global public health problem.1–3 In 2014, the national annual number of OHCA of cardiac origin was 70 000 in Japan,4 with an increase in the number of elderly patients.5 As the ageing population is expected to grow further in Japan6 as well as other developed nations, the increased incidence of OHCA in elderly patients will become a further burden.5 There is, therefore, a compelling need to develop optimal management strategies and policies to treat OHCA in elderly patients.

To date, encouraging results of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) for patients who had OHCA have been shown as a highly advanced medical treatment.7–10 The recommendation of ECPR for cardiac arrest is class 2b based on the 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science.1 In addition, the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation recommends the consideration of ECPR for cases such as paediatric resuscitation and asthma-related cardiac arrest.11 Furthermore, subsequent observational studies have demonstrated that the utilisation of ECPR was associated with improved survival compared with conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in OHCA patients with potentially treatable conditions.12 13 The indication of ECPR for OHCA might, therefore, be extended in the future. However, the utilisation of ECPR for elderly patients—a population with limited cardiovascular and pulmonary reserve—remains controversial.14 Indeed, ECPR clinical protocols are likely to include an age limit as a contraindication of ECPR, whereas there is not sufficient supporting evidence.15 Although some reports suggest that an age of ≥75 years should be a contraindication for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support,16 17 a literature using the international Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry suggested that age should not be a bar against the consideration of the utilisation of ECMO in elderly patients.18 Furthermore, a recent systematic review of prognostic factors for ECPR recipients following OHCA has failed to establish a link between age and poor prognosis following ECPR.19

To address this knowledge gap in the literature, we assessed the neurological outcomes and mortality of elderly patients who had OHCA who underwent ECPR, using consecutive data from a critical care centre in Osaka, the second largest prefecture in Japan.

Material and methods

Study design and settings

This retrospective analysis of medical records from a single centre in Japan was conducted at Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital, a critical care centre approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and located in the northern city of Suita, Osaka, Japan. This hospital covers a population of approximately 1 million residents, treating 200–250 patients who had OHCA annually. In this area, for all patients who had OHCA including suspected OHCA (based on the information provided by the emergency telephone call from the patient containing keywords that indicate heart attack or cardiac arrest), the Fire-Defense Headquarters requested the mobilisation of a physician-staffed ambulance from our hospital. All patients who had OHCA are transported to the hospital, regardless of whether return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved (ie, none are declared dead at the scene). The institutional review board of Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital granted a waiver of informed consent.

Selection of participants and data collection

We abstracted data from medical records of patients who had consecutive OHCA aged ≥18 years old who underwent17 and September 2013. In our centre, all patients who had OHCA including emergency medical service-witnessed cases are recorded in the form of an electronical medical chart as our data resource. We abstracted necessary data from the medical chart for this study. For all patients who had OHCA, the emergency physician assessed the indications for ECPR during transportation and then informed the hospital medical staff in the emergency department via telephone. To confirm the eligibility of ECPR for patients who had OHCA, in our critical care medical centre, the on-site physicians used mobile phones to discuss the eligibility of ECPR with other in-hospital attending physicians. In the present study, approximately 80% of OHCA cases were transported by physician-staffed ambulances, and all patients were treated by emergency physicians and the Advanced Cardiac Life Support guidelines of the emergency department.20

Indications of ECPR for patients who had OHCA are shown in table 1. Absolute indications for ECPR were OHCA patients with refractory ventricular fibrillation (Vf), defined as sustained Vf after three attempts of defibrillation with potentially treatable conditions. Relative indications for ECPR were OHCA patients with presumably treatable conditions with pulseless electrical activity or asystole, hypothermia and drug intoxication. Patient age was not considered when using ECPR. Patients with the following were excluded: stroke, terminal malignancy, cirrhosis, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, poor daily living activities and assessed as ‘inadequate indications’ for ECPR by the team leader.

Table 1.

Indications for ECPR for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest at Senri Critical Care Medical Centre

| Following indications are applied when it is expected that ECMO be implemented within 45 min after cardiac arrest | |

| Indication criteria | |

| Absolute indication | Refractory Vf (persistent Vf following at least three unsuccessful countershocks) |

| Relative indication | Presumed treatable conditions with PEA/asystole* |

| Hypothermia | |

| Drug intoxication | |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Stroke | |

| Terminal malignancy | |

| Cirrhosis | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |

| Poor activities of daily living | |

| In a case who the team leader judged ‘inadequate indication’ for ECPR | |

*Judged by an emergency physician who treats the patient with physician-staffed ambulance according to the initial rhythm.

ECMO, extracorporeal membranous oxygenation; ECPR, extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; Vf, ventricular fibrillation.

ECMO management and postresuscitation care

The final decision to initiate ECPR depended on the opinions of the attending physicians. To achieve successful and rapid implementation, the ECMO team consisted of emergency physicians, cardiologists and clinical engineers. Chest compression was continued until starting ECMO. The percutaneous cannulation technique for venous and arterial ECMO accesses was used to deliver ECMO with a 13.5 F arterial cannulae or a 19.5 F venous cannulae via femoral artery or vein. The cannulation was performed in the ED or ED adjoining cardiac catheterisation room. Urgent coronary angiography was performed for OHCA patients with a suspected cardiac origin. The patients diagnosed as acute myocardial infarction were performed a primary percutaneous intervention with conventional technique for culprit lesions. All postresuscitated patients after implementation of ECMO received guideline recommended care,1 regardless of age and clinical diagnosis. The patients were provided adequate oxygenation, vasopressors and fluid administration to maintain systolic arterial pressure at 90 mm Hg and/or mean atrial pressure at 65 mm Hg, target temperature management at 34°C. The weaning criteria of ECMO were as follows: (1) the patient was haemodynamically stable and (2) adequately oxygenated with an ECMO flow of 1500 mL/min. In cases of irreversible multiple organ failure or severe neurological damage equivalent to brain death, withdrawal of ECMO was considered.

Data collection and quality control

The measured variables were patient demographics, prehospital characteristics (ie, time-course, initial rhythm, presence of ROSC and managements), resuscitation time-course, therapeutic intervention (therapeutic hypothermia and intra-aortic balloon pumping) and the cause of cardiac arrest. The attending physician at the morning conference decided the most likely cause of cardiac arrest. Prehospital variables were collected by the information from paramedics and the emergency physicians who treated the patient with physician-staffed ambulance. The resuscitation time-course was collected by the emergency physician who treated the patient with the physician-staffed ambulance and medical staff in the emergency department. Other measurements including postresuscitation care were recorded by the attending physician using a standardised data collection form.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest were 1 month neurologically favourable outcomes and survival. Neurologically favourable outcomes were defined as a Cerebral Performance Categories (CPC) score of 1 or 2.21 The attending physician in-charge of the rounds or the outpatient determined the CPC score.

Statistical analyses

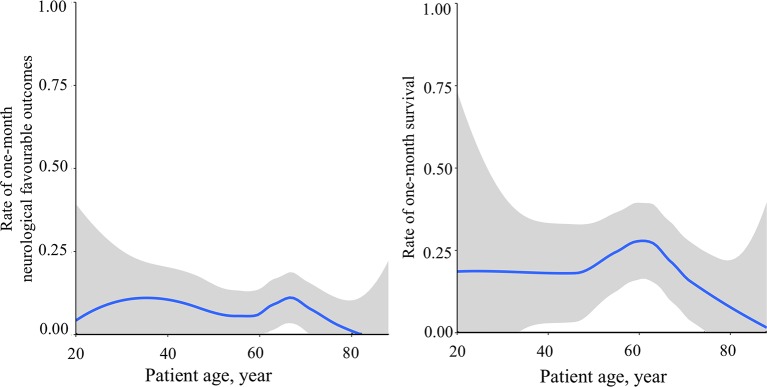

Continuous data were presented as the median (IQR) with differences analysed using the Mann-Whitney test, while categorical data were expressed in percentages (n/N) with differences analysed using χ2 test or Fischer’s exact test as appropriate. We also illustrated the associations between age and each outcome by using a LOWESS smoother with calculating 95% CI using a bootstrap method.

To determine the association between advanced age and each outcome, we fitted multivariable logistic regression models using: (1) age as a continuous variable and (2) age as a categorical variable (<50 years, 50–59 years, 60–69 years and ≥70 years). These age categories were determined based on the association between age and outcomes. Potential confounding factors were selected based on a priori knowledge2 8 10 22 and factors that showed a significant association with the outcome in the univariate analysis. Variables included, shockable rhythm, witnessed arrest, CPR by bystanders, rearrest after ROSC during transportation and pH on hospital arrival. Shockable rhythm was defined as Vf and pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) at the initial assessment of paramedics or staff physicians. While the use of therapeutic hypothermia was significantly associated with the survival outcome, we did not include this variable in multivariable models, because this variable is an intermediate between ECPR implementation and outcomes. ORs and CIs were then calculated. In addition, we have summarised the results in patients aged ≥75 years (n=22), which is the suggested upper limit of age for implementation of ECMO support.16 17 We analysed data using STATA V.15.0 and R statistical software (V.3.4.0).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in this study.

Results

During the study period, 152 consecutive OHCA underwent ECPR. Among them, we excluded five patients without follow-up as they were transported to another hospital for further advanced care (eg, implementation of left ventricular assistive device) and another three patients with traumatic arrest, leaving 144 patients eligible for our analysis. The median patient age was 63 (IQR 55–71) years, and 15% of patients were women (table 2). In 38% of cases, a bystander performed CPR. Shockable rhythm (ie, Vf and pulseless VT) accounted for 61% of cases. Physician-staffed ambulances transported 81% of cases. The median time from call to arrival at the hospital was 41 min (IQR 33–50 min) and from call to implementation of ECMO was 57 min (IQR 49–70 min). On admission, the median pH value was 6.95, and median serum lactate level was 12.5 mmol/L. For postresuscitation therapy, therapeutic hypothermia was completed in 44% of patients and an intra-aortic balloon pumping was used for 77% of patients. Approximately 70% of cardiac arrests were caused by acute myocardial infarction.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients who had out-of-hospital cardiac arrest receiving ECPR

| Overall | Neurologically favourable outcomes | Survival outcome | |||||

| (n=144) | CPC 1–2 (n=10) |

CPC 3–5 (n=134) |

P values | Survived (n=28) |

Not survived (n=116) |

P values | |

| Baseline characteristics | |||||||

| Age, year, median (IQR) | 63 (55–71) | 62 (48–68) | 64 (55 to 72) | 0.30 | 61 (55–67) | 64 (55–72) | 0.23 |

| Women, n (%) | 22 (15) | 1 (10) | 21 (16) | 0.63 | 3 (11) | 19 (16) | 0.56 |

| Prehospital characteristics, n (%) | |||||||

| Witnessed cases* | 25 (18) | 2 (20) | 24 (18) | 0.87 | 8 (29) | 17 (16) | 0.11 |

| CPR by bystanders† | 54 (38) | 3 (30) | 51 (38) | 0.61 | 7 (25) | 47 (41) | 0.13 |

| Shockable rhythm‡ | 88 (61) | 7 (70) | 81 (60) | 0.55 | 22 (79) | 66 (57) | 0.04 |

| Physician-staffed ambulance | 117 (81) | 6 (60) | 11 (83) | 0.07 | 21 (75) | 96 (83) | 0.35 |

| Rearrest after ROSC during transportation§ | 14 (10) | 3 (30) | 11 (8) | 0.03 | 8 (29) | 6 (5) | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation time courses, median (IQR) | |||||||

| Call to hospital, min | 41 (33–50) | 34 (32–42) | 42 (33–50) | 0.12 | 41 (32 to 47) | 41 (34–51) | 0.41 |

| Call to ECPR, min | 57 (49–70) | 60 (50–90) | 57 (49–67) | 0.39 | 60 (51–78) | 56 (48–68) | 0.40 |

| Call to ROSC¶ or ECPR, min | 54 (46–65) | 53 (27–64) | 54 (46–65) | 0.57 | 52 (32–66) | 54 (46–65) | 0.57 |

| Blood test on admission | |||||||

| pH, mean (IQR) | 6.95 (6.80–7.10) | 6.82 (7.08–7.23) | 6.95 (6.80–7.09) | 0.23 | 6.99 (6.86–7.19) | 6.94 (6.78–7.08) | 0.12 |

| Serum lactate, mmol/L, mean (IQR) | 12.5 (9.8–14.7) | 13.3 (9.6–14.6) | 12.4 (9.8–14.7) | 0.93 | 11.1 (9.2–14.8) | 12.5 (10.5–14.7) | 0.41 |

| Interventions, n (%) | |||||||

| Therapeutic hypothermia (completed) | 63 (44) | 5 (50) | 58 (43) | 0.68 | 19 (68) | 44 (38) | <0.004 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pumping | 111 (77) | 8 (80) | 103 (77) | 0.82 | 24 (86) | 87 (75) | 0.23 |

| Causes of cardiac arrest, n (%) | 0.68 | 0.59 | |||||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 100 (69) | 7 (70) | 93 (70) | 19 (68) | 81 (70) | ||

| Structural heart disease | 11 (8) | 0 (0) | 11 (8) | 2 (7) | 9 (8) | ||

| Aortic dissection | 6 (4) | 0 (0) | 6 (4) | 0 (0) | 6 (5) | ||

| Arrhythmia | 6 (4) | 2 (20) | 4 (3) | 3 (11) | 3 (3) | ||

| Asphyxia | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | ||

| Other** | 7 (5) | 0 (0) | 7 (5) | 1 (4) | 6 (5) | ||

| Unknown | 12 (8) | 1 (10) | 11 (8) | 3 (11) | 9 (8) | ||

| Admission year | 0.32 | 0.20 | |||||

| 2005 | 4 (3) | 1 (10) | 3 (2) | 2 (7) | 2 (2) | ||

| 2006 | 18 (13) | 1 (10) | 17 (13) | 5 (18) | 13 (11) | ||

| 2007 | 15 (10) | 0 (0) | 15 (11) | 2 (7) | 13 (11) | ||

| 2008 | 19 (13) | 2 (20) | 17 (13) | 3 (11) | 16 (14) | ||

| 2009 | 7 (5) | 0 (0) | 7 (5) | 2 (7) | 5 (4) | ||

| 2010 | 19 (13) | 1 (10) | 18 (13) | 3 (11) | 16 (14) | ||

| 2011 | 26 (18) | 1 (10) | 25 (19) | 3 (11) | 23 (20) | ||

| 2012 | 22 (15) | 1 (10) | 21 (16) | 2 (7) | 20 (17) | ||

| 2013 | 14 (10) | 3 (30) | 11 (8) | 6 (21) | 8 (7) | ||

*Including witnessed by emergency medical service (EMS).

†Including patients witnessed by EMS and those who had CPR by the EMS.

‡Ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia.

§Defined as recardiac arrest after spontaneous circulation sustained for ≥20 min during transportation.

¶Defined as spontaneous circulation sustained for ≥20 min.

**Accidental hypothermia, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, septic shock and subarachnoid haemorrhage.

CPC, Cerebral Performance Categories; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECPR, extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation.

Overall, the proportion of neurologically favourable outcomes was 7% (95% CI 4% to 13%), while survival was 19% (95%CI 14% to 27%) in patients who had OHCA. Patients with neurologically favourable outcomes were more likely to have rearrest after ROSC during transportation compared with those without (p=0.03). For 1-month survival, survived patients were more likely to have shockable rhythm, rearrest after ROSC during transportation and to be treated with therapeutic hypothermia compared with non-survived patients (all, p<0.05).

Figure 1A,B illustrates the associations between age and each outcome. The rate of 1-month neurologically favourable outcomes had a biphasic association curve with a peak around age 40 years and 65 years (figure 1A). The survival rate increased from age 50 years with a peak around age 60 years and decreased thereafter (figure 1B). The survival rate around age 70 years became similar to those of age <50 years.

Figure 1.

The associations between and 1-month survival and neurologically favourable outcomes.

Table 3 demonstrates the association between age and outcomes. Overall, in the unadjusted models using age as a continuous variable, age was non-significantly associated with the worse 1-month neurological outcomes and survival. After the adjustment for potential confounders, while advanced age was non-significantly associated with worse neurological outcomes (adjusted OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.01), p=0.08), the association between advanced age and poor survival rate was significant (adjusted OR 0.96 (95% CI 0.93 to 0.99), p=0.04). Similar associations were found in the analyses using age as a categorical variable. Compared with age <50 years, age ≥70 years was associated with poor neurological outcomes (adjusted OR 0.08 (95% CI 0.01 to 1.00), p=0.051) and significantly associated with the worse survival in the adjusted model (adjusted OR 0.14 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.80), p=0.03). Among patient aged 75 years, which is the suggested upper limitation of age for implementation of ECPR, only three patients survived, and no patients survived with neurologically favourable outcomes.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable associations between age categories and outcomes in patients who had OHCA

| Number of cases (%) | Unadjusted ORs (95% CI) | P values | Adjusted ORs (95% CI)* | P values | |

| Primary analysis | |||||

| Age as continuous variable | |||||

| Neurologically favourable outcomes | 10 (7) | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) | 0.24 | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.01) | 0.08 |

| One-month survival | 28 (19) | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) | 0.31 | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Age as categorical variable | |||||

| Neurologically favourable outcomes | |||||

| Age 18–49 years (n=23) | 3 (13) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Age 50–59 years (n=35) | 1 (3) | 0.20 (0.02 to 2.01) | 0.17 | 0.15 (0.01 to 1.87) | 0.18 |

| Age 60–69 years (n=44) | 5 (11) | 0.85 (0.19 to 3.95) | 0.84 | 0.56 (0.10 to 3.25) | 0.94 |

| Age ≥70 years (n=42) | 1 (2) | 0.16 (0.02 to 1.66) | 0.13 | 0.08 (0.01 to 1.00) | 0.051 |

| One-month survival | |||||

| Age 18–49 years (n=23) | 5 (22) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||

| Age 50–59 years (n=35) | 7 (20) | 0.90 (0.25 to 3.27) | 0.87 | 0.74 (0.17 to 3.34) | 0.70 |

| Age 60–69 years (n=44) | 12 (27) | 1.35 (0.41 to 4.45) | 0.62 | 0.83 (0.20 to 3.40) | 0.80 |

| Age ≥70 years (n=42) | 4 (10) | 0.38 (0.09 to 1.58) | 0.18 | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.80) | 0.03 |

*Adjusted for witnessed arrest, bystander CPR, shockable rhythm, re-arrest after ROSC during transportation, and pH on hospital arrival.

OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis from an urban critical care hospital, we found that advanced age was associated with the lower rate of 1-month survival and neurologically favourable outcomes in patients who had OHCA who underwent ECPR. The rate of neurologically favourable outcomes and 1-month survival decreased after age 70 years old. In addition, no patient aged ≥75 years survived with neurologically favourable outcomes at 1 month after cardiac arrest. These findings provide valuable clues for creating optimal strategy for elderly patients who had OHCA in the ageing era.

Our study observed that age ≥70 years was associated with the lower survival rate, and no patients aged ≥75 years survived with neurologically favourable outcomes at 1 month after cardiac arrest. Although previous studies reported that ECPR was more effective in treating patients who had OHCA than conventional CPR, these studies did not assess the effect of advanced age; their findings were based on studies limited to patients aged <75 years.9 10 A multicentre prospective observational study in Japan demonstrated that the survival rate at 1 month after cardiac arrest was significantly higher in the ECPR group than in the non-ECPR group (27% vs 6%) and that the proportion of neurologically favourable outcomes was also significantly higher in the ECPR group (12.3% vs 1.5%).10 Our results that overall 1-month survival rate of 20% and 1-month survival with neurologically favourable outcomes of 8% are comparable results with these previous findings,9 10 despite we included patients aged ≥75 years. Therefore, focusing on the elderly patients, our findings might suggest limitations in using ECPR to treat elderly patients who had OHCA.

The reasons for the observed lack of effectiveness of ECPR among elderly patients are likely multifactorial. First, consistent with the elderly being the population with limited cardiovascular and pulmonary reserve, the survival rate of patients who had OCHA was lower in older patients than in younger patients.23 An observational study in the USA demonstrated that advanced age was a factor associated with lower survival rate at discharge among patients who had OHCA (19.4% for ≤80 years vs 9.4% for 80–89 years, and 4.4% for ≥90 years).23 Second, shorter duration from cardiac arrest to ROSC was a critical factor for neurologically favourable outcomes among patients who had OHCA. Indeed, in an observational study in the USA, shorter duration of CPR was associated with neurologically favourable outcomes—90% of patients with neurologically favourable outcomes required less than 16 min of CPR.24 In our findings, the median time from cardiac arrest to ROSC or implementing of ECMO was 54 min, which is considerably longer than in the previous study in the USA.24 However, patients who require ECPR are ‘non-responders’ to conventional CPR within 20 min.12 In addition, another ECPR study also showed a lengthy median time from arrest to ROSC of 50 min in patients who had OHCA, consistent with our findings.8 Due to the vulnerability of elderly patients, elderly patients might not withstand the prolonged CPR compared with younger age. Taken together, advanced age as a vulnerable population and a longer CPR duration may help explain the lack of effectiveness of ECPR for elderly patients who had OHCA in the present study.

Importantly, the cost burden of ECPR is also significant. In Japan, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of ECPR was approximately £57 000 per quality-adjusted life-year.25 Considering the acceptable ICER for introducing a new treatment is approximately £20 000–£30 00026; this financial burden is unacceptably high. Furthermore, another Japanese study suggested that the average cost for treating a patient who had OHCA was approximately £1250.27 Ageing and its associated costs are increasing, constituting an enormous financial burden throughout the developed world. Given this significant financial burden and our present observations, indications of ECPR in elderly patients who had OHCA might be limited with respect to cost-effectiveness. Our observations facilitate further investigations to elucidate the cost-effectiveness of ECPR for elderly patients who had OHCA.

Despite the significant healthcare resource burden of ECPR, the present study did not demonstrate the effectiveness of ECPR for elderly patients who had OHCA. However, this does not indicate that CPR should not be used for elderly patients. Although advanced age could be a factor associated with poor outcomes in patients who had OHCA in the present study, this factor alone does not appear to be a well-established criterion to deny patients for conventional CPR based on a previous report.23 Additionally, experts say that decisions regarding termination of resuscitation should not be based on age.28 However, given our present findings regarding poor outcomes among elderly patients and the extremely high cost of ECPR, the indication of ECPR for elderly patients should be carefully considered in this ageing era.

Limitations

We acknowledge several potential limitations to our study. First, as our sample consisted of retrospective data from a single centre in Japan, our inferences might not be generalisable to other healthcare settings. However, the observed association has plausible mechanisms and persisted across different analytical assumptions. Although formal validation of the study in other healthcare settings is warranted, our inferences likely present in different practical settings. Second, there was lack of data on daily living activities, medication use and comorbidities before cardiac arrest including a poorer neurological state prearrest. In addition, information on whether the ECPR was implemented during active chest compressions and on the results of percutaneous coronary intervention was also not available. However, an experienced emergency physician or cardiologist assessed whether the cause of cardiac arrest was treatable and appropriate for ECPR based on information gained from the person accompanying the patient and the situation of cardiac arrest. Third, our study might include ECMO cases for persistent hypotension after ROSC. However, the association was significant after adjusting for the potential persistent hypotension after ROSC (ie, rearrest after ROSC during transportation). Finally, although the indication for ECPR was assessed based on the protocol and by experienced physicians, our data are subject to selection bias. In general, however, the indication of ECPR for elderly patients was stricter than that for younger patients, which might have biased our conclusions towards the null.

Conclusions

In our analysis of consecutive OHCA data from a critical care hospital in an urban area of Japan, we found that advanced age was associated with the lower rate of 1-month survival in patients who had OHCA who underwent ECPR. The rate of neurologically favourable outcomes and 1-month survival decreased after age 70 years old. In addition, no patient aged ≥75 years survived with neurologically favourable outcomes at 1 month after cardiac arrest. Although larger studies are required to confirm these results, our findings suggest that ECPR may not be beneficial for patients who had OHCA aged ≥70 years. While the eligibility of ECPR should not be determined by age as a single variable, our findings might help improve the survival rate and neurological outcomes of elderly patients who had OHCA and facilitate further observation, intervention and discussion regarding the utilisation of ECPR for elderly patients who had OHCA.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are deeply indebted to all of the staff and physicians of Senri Critical Care Medical Centre, Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital.

Footnotes

Contributors: TG, SM, NT, HS, YH and TK planned the study. TK supervised and provided statistical advice on study design. TG analysed the data. TG drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. TG takes responsibility for the paper as a whole. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The institutional review board of Osaka Saiseikai Senri Hospital approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data are not allowed for public use by institutional review board.

References

- 1. 2017 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations Summary. Circulation 2017;136:S250–605. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Spencer B, Chacko J, Sallee D. American Heart Association. The 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care: an overview of the changes to pediatric basic and advanced life support. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2011;23:S639–946. 10.1016/j.ccell.2011.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Resuscitation Council. Guidelines for Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2010;81:1219–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ambulance Service Planning Office of Fire and Disaster Management Agency of Japan. Effect of first aid for cardiopulmonary arrest. http://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/topics/houdou/h25/2512/251218_1houdou/01_houdoushiryou.pdf (accessed 03 Mar 2015).

- 5. Kitamura T, Morita S, Kiyohara K, et al. Trends in survival among elderly patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a prospective, population-based observation from 1999 to 2011 in Osaka. Resuscitation 2014;85:1432–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muramatsu N, Akiyama H. Japan: super-aging society preparing for the future. Gerontologist 2011;51:425–32. 10.1093/geront/gnr067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kagawa E, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, et al. Assessment of outcomes and differences between in- and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients treated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation using extracorporeal life support. Resuscitation 2010;81:968–73. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maekawa K, Tanno K, Hase M, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of cardiac origin: a propensity-matched study and predictor analysis. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1186–96. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827ca4c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson NJ, Acker M, Hsu CH, et al. Extracorporeal life support as rescue strategy for out-of-hospital and emergency department cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2014;85:1527–32. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sakamoto T, Morimura N, Nagao K, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation versus conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a prospective observational study. Resuscitation 2014;85:762–8. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nolan JP, Soar J, Zideman DA, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 1. Executive summary. Resuscitation 2010;81:1219–76. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim SJ, Jung JS, Park JH, et al. An optimal transition time to extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for predicting good neurological outcome in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a propensity-matched study. Crit Care 2014;18:535 10.1186/s13054-014-0535-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang CH, Chou NK, Becker LB, et al. Improved outcome of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest--a comparison with that for extracorporeal rescue for in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2014;85:1219–24. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Riggs KR, Becker LB, Sugarman J. Ethics in the use of extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults. Resuscitation 2015;91:73–5. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Choi DH, Kim YJ, Ryoo SM, et al. Extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2016;3:132–8. 10.15441/ceem.16.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kolla S, Lee WA, Hirschl RB, et al. Extracorporeal life support for cardiovascular support in adults. Asaio J 1996;42:M809–18. 10.1097/00002480-199609000-00103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Massetti M, Tasle M, Le Page O, et al. Back from irreversibility: extracorporeal life support for prolonged cardiac arrest. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:178–83. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mendiratta P, Wei JY, Gomez A, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the elderly: a review of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Asaio J 2013;59:211–5. 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31828fd6e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Debaty G, Babaz V, Durand M, et al. Prognostic factors for extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation recipients following out-of-hospital refractory cardiac arrest. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2017;112:1–10. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122(Suppl 3):S729–67. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prohl J, Röther J, Kluge S, et al. Prediction of short-term and long-term outcomes after cardiac arrest: a prospective multivariate approach combining biochemical, clinical, electrophysiological, and neuropsychological investigations. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1230–7. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000261892.10559.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iwami T, Kawamura T, Hiraide A, et al. Effectiveness of bystander-initiated cardiac-only resuscitation for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation 2007;116:2900–7. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.723411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim C, Becker L, Eisenberg MS. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in octogenarians and nonagenarians. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:3439–43. 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reynolds JC, Frisch A, Rittenberger JC, et al. Duration of resuscitation efforts and functional outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: when should we change to novel therapies? Circulation 2013;128:2488–94. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Asaka K, Aoki N. ECPR Indication Criteria -From the Cost Effective Analysis in SAVE-J Study. Circulation 2013;128:A305. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Devlin N, Parkin D. Does NICE have a cost-effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? A binary choice analysis. Health Econ 2004;13:437–52. 10.1002/hec.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fukuda T, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, et al. Health care costs related to out-of-hospital cardiopulmonary arrest in Japan. Resuscitation 2013;84:964–9. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wuerz RC, Holliman CJ, Meador SA, et al. Effect of age on prehospital cardiac resuscitation outcome. Am J Emerg Med 1995;13:389–91. 10.1016/0735-6757(95)90120-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.