Abstract

Objective

We aimed to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to clarify the association between white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) and carotid artery (CA) stenosis.

Study design

Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Participants

CA stenosis was set at ≥50%, and WMHs were assessed by MRI and evaluated quantitatively or semiquantitatively.

Data sources

A comprehensive literature search was performed in PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library for studies evaluating the association between WMHs and CA stenosis ≥50% from inception to 13 September 2017.

Main outcomes and measures

Standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI was used to evaluate the association between WMHs and CA stenosis. Results were presented in a forest plot with a fixed-effects model or random-effects model. We assessed the quality of included studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Funnel plots and Egger’s and Begg’s tests were conducted to assess publication bias. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the influence of each individual study.

Results

Eight studies enrolling 677 patients were included. There was a positive relationship between the total WMHs and CA stenosis, with a pooled fixed-effects SMD of 0.326 (95% CI 0.194 to 0.459, p=0.000). Heterogeneity and publication bias were low among these studies. Subgroup analysis of three studies enrolling 225 patients showed an association between periventricular WMHs and CA stenosis, with a pooled fixed-effects SMD of 0.412 (95% CI 0.202 to 0.622, p=0.000).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed that the total WMHs and periventricular WMHs were associated with CA stenosis. WMHs may be considered as an individual risk stratification score when choosing a proper plan for therapy of CA stenosis.

Keywords: systematic review, meta-analysis, white matter hyperintensities, carotid artery stenosis, magnetic resonance imaging

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to show the association between the subtypes of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) and carotid artery (CA) stenosis.

Our analysis only included studies in which all WMHs were assessed using MRI, and the including criterion for the severity of CA stenosis was set at ≥50%.

Only three of the eight included studies reported data on the association between the subtypes of WMHs and CA stenosis, and the standardised mean difference is small, which made the conclusion less persuasive.

Introduction

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) are common incidental finding on brain imaging1 and in silent cerebrovascular diseases.2 They are a marker for chronic neurological damages that increase the risk for stroke, dementia and death.3 However, the aetiology and mechanisms of WMHs remain unclear. Besides age and small-vessel diseases (SVD), increasing evidence shows a relationship between carotid artery (CA) stenosis and WMHs.4–8 However, some studies differ in their results.9–13

To our knowledge and according to the present studies, there are mainly two factors leading to the inconsistencies in the results. First, WMHs were assessed using MRI in some studies and using CT in other studies.4–13 The resolution of MRI and CT in assessing WMHs is quite different. Second, the inclusion criteria for the severity of CA stenosis vary greatly among the present studies.4–13 A previous meta-analysis that attempted to systematically evaluate this question included studies in which WMHs were assessed using CT or MRI.14 The other systematic review on the topic set the inclusion criterion for the severity of CA stenosis at ≥30%, which was insufficient to cause WMHs. However, a meta-analysis was not carried out owing to heterogeneity.15 Both of these studies did not analyse the subtypes of WMHs, which are probably caused by different pathogenic mechanisms.

In view of these considerations, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, and included studies in which all WMHs were assessed using MRI, and the inclusion criterion for the severity of CA stenosis was set at ≥50%. The association between the subtypes of WMHs and CA stenosis was further analysed. If the CA stenosis ≥50% is associated with WMHs, WMHs may be considered as an individual risk stratification score when choosing a proper therapeutic plan for CA stenosis.

Methods

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library from inception to 13 September 2017. In addition, we searched the reference lists of all identified relevant publications and relevant reviews. Search strings were combinations of medical subject headings or the EMBASE tree tool, including ‘leukoaraiosis’ or ‘white matter lesion’ and ‘carotid artery diseases’ and free-text terms. A representative primary search strategy conducted in the PubMed database is available in online supplementary data I.

bmjopen-2017-020830supp001.pdf (54.8KB, pdf)

Inclusion criteria

We included studies (1) that examined human subjects, (2) that were published in full and in English, (3) where the inclusion criterion for the severity of CA stenosis was at ≥50%, (4) that assessed WMHs using 1.5 T or 3.0 T MRI, and (5) that included a quantitative or semiquantitative assessment of WMHs imaging in patients with CA stenosis. In case of duplicated published cohorts, we included the studies with the longest follow-up and the greatest number of patients.

Selection of studies

One review author (HY) acquired the titles and abstracts from a database search. Two authors (HY and JQ) independently screened the titles and abstracts of potentially eligible studies according to the inclusion criteria. Three authors (HY, JQ and YW) screened the full text of potentially eligible studies. We resolved disagreements by consensus.

Assessment of risk of bias of the included studies

Two review authors (HY and JQ) independently evaluated the quality of the included studies according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).16 A study awarded six or more stars was defined as a high-quality study.17 We resolved any disagreements by consensus.

Data extraction

Two review authors (HY and JQ) independently extracted data from the included studies, including the first author’s name, publication year, country, characteristics and number of subjects of each study, vascular imaging methods, severity of CA stenosis, the rating method and location of WMHs, and the results of the relationship between WMHs and CA stenosis. To perform a quantitative meta-analysis, the mean values and SD of the total, deep and periventricular WMHs scores, as well as the number of subjects, were obtained by direct extraction or conversion.18–20

All extracted data were confirmed by a third review author (YW), with discrepancies resolved by consensus. If the raw data were not readily available in the manuscript, we tried to contact the author. We performed our review referring to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement.21

Statistical analysis

STATA V.12.0 was applied to analyse the extracted data. We quantified the strength of the association between WMHs and CA stenosis using standardised mean differences (SMDs) and their corresponding 95% CI. Heterogeneity was assessed by χ2 and I2 values. If the p value of χ2 was less than 0.1, homogeneity was rejected. For the I2 statistic, 25%, 50% and 75% were the thresholds for low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively.22 SMD was calculated with the fixed-effects model, using the inverse variance approach when no significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies. Otherwise, when significant heterogeneity among the studies was detected, a random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird) was used. SMDs <0.50 were considered small according to Cohen’s (d) rules of thumb.18 Subgroup analyses were performed based on the different locations of WMHs, including periventricular and deep. Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the influence of each individual study. Publication bias was examined by funnel plots and Egger’s and Begg’s tests. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement statement

Patients and the public were not involved.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

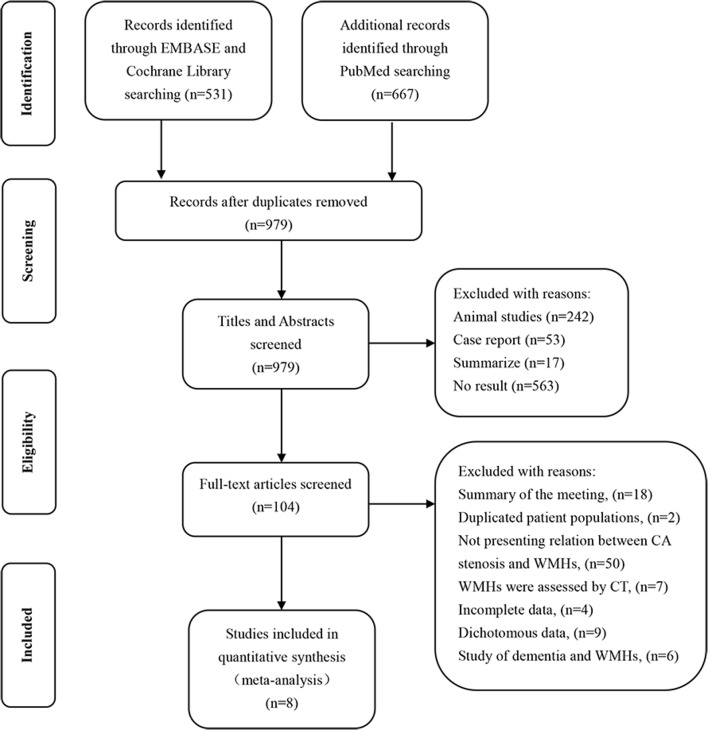

The search and selection process for our meta-analysis was outlined in figure 1. Our detailed search identified 1198 studies through PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library. After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts from the remaining 979 studies were screened and 104 potentially eligible studies were retained. The full-text versions of these 104 studies were retrieved and 96 studies were excluded because of the reasons listed in figure 1. A total of eight studies comprising 677 patients were included for analysis. The NOS scores ranged from 6 to 8 (table 1). Table 2 showed the primary characteristics of the included studies published between 2006 and 2017. Earlier studies did not meet our inclusion criteria and requirement for data extraction.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses group statement. CA, carotid artery; WMHs, white matter hyperintensities.

Table 1.

Results of quality assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies

| First author, year | Representativeness of the exposed cohort | Selection of the non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure to implants | Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | Total score |

| Ammirati,4 2017 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ ★ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 8 |

| Sahin,5 2015 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ☆ | ★ | 7 |

| Schulz,9 2013 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ ★ | ★ | ★ | ☆ | 8 |

| Cheng,10 2012 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

| Scherr,11 2012 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ ★ | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 |

| Chuang,6 2011 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 |

| Enzinger,7 2010 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ ★ | ★ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 |

| Patankar,8 2006 | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★ | ★☆ | ★ | ★ | ★ | 8 |

★Score 1 point, ☆score 0 point.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included

| First author, year | Country | Subjects | Subjects (n) | Male (n) | Age, years Mean±SD |

Severity of CA stenosis | Vascular image | WMHs rating method | WMHs location | Result | |

| Stenosed | Control | ||||||||||

| Ammirati,4 2017 | Italy | Asymptomatic | 27 | 40 | 38 | 69±8 | Stenosis ≥50% | DUS | Volumetric | Total | Positive |

| Sahin,5 2015 | Turkey | Asymptomatic | 29 | 29* | 18 | 68.62±9.22 | Unilateral stenosis ≥70% | CTA, MRA, DSA | Scheltens Scale | Deep Periventricular |

Positive |

| Schulz,9 2013 | UK | Symptomatic† | 33 | 33* | NA | NA | Unilateral stenosis ≥70% | CTA, MRA, DUS | ARWMC Scale | Total | Negative |

| Cheng,10 2012 | Taiwan | Asymptomatic | 17 | 26 | 24 | NA | Unilateral stenosis ≥70% | DUS, MRA | Scheltens Scale | Total | Negative |

| Scherr,11 2012 | Austria | Asymptomatic | 62 | 150 | 119 | 70.2±9.06 | Stenosis ≥50% | DUS | Modified Fazekas Scale | Total | Negative |

| Chuang,6 2011 | Taiwan | Symptomatic‡ | 106 | 106* | 64 | 68.7±9.2 | Unilateral stenosis >60% | DUS, MRA | Fazekas Scale | Deep Periventricular |

Positive |

| Enzinger,7 2010 | Austria | Asymptomatic Symptomatic§ |

97 | 97* | 68 | 69.1±10.2 | Unilateral stenosis >70% | DUS, MRA | Volumetric | Total | Positive |

| Patankar,8 2006 | UK | Asymptomatic | 55 | 35 | NA | NA | Stenosis >70% | DUS | Scheltens Scale | Deep Periventricular |

Positive |

*Intraindividual side-to-side comparison.

†Transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke.

‡Transient (lasting <24 hours) or minor neurological deficits in the territory of the stenosed CA.

§Subjects with a supratentorial infarct exceeding 1.5 cm in diameter were excluded.

ARWMC, age-related white matter changes;CA, carotid artery; CTA, CT angiography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; DUS, Doppler ultrasonography; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; NA, not applicable; WMHs, white matter hyperintensities.

WMHs and CA stenosis

The results of the eight eligible studies including 677 patients were pooled for the meta-analysis, with no evidence of heterogeneity (χ2=5.71, df=7 (p=0.573); I2=0). The summarised fixed-effects SMD of 0.326 (95% CI 0.194 to 0.459, p=0.000) suggested a positive relationship between WMHs and CA stenosis (figure 2). All eight studies showed a positive association between WMHs and CA stenosis, but four of them did not have a statistically significant SMD.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of the relationship between white matter hyperintensities and carotid artery stenosis. Studies are listed by date. Squares indicate point estimates for effect size (SMD), with the size proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Diamonds indicate pooled estimates. Lines represent 95% CI. The solid vertical line indicates the null effect. I2 listed below the forest plot. SMD, standardised mean difference.

WMHs subtypes and CA stenosis

Subgroup analysis of the three eligible studies including 225 patients showed that CA stenosis remained associated with periventricular WMHs (SMD: 0.412, 95% CI 0.202 to 0.622, p=0.000; figure 3), with no evidence of heterogeneity (χ2=0.29, df=2 (p=0.864); I2=0). CA stenosis was also associated with deep WMHs (SMD: 0.603, 95% CI 0.106 to 1.100, p=0.017; figure 4), with evidence of high heterogeneity (χ2=8.85, df=2 (p=0.012); I2=77.4%).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the relationship between periventricular white matter hyperintensities and carotid artery stenosis. Squares indicate point estimates for effect size (SMD), with the size proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Diamonds indicate pooled estimates. Lines represent 95% CI.The solid vertical line indicates the null effect. I2 listed below the forest plot. SMD, standardised mean difference.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of the relationship between deep white matter hyperintensities and carotid artery stenosis. Squares indicate point estimates for effect size (SMD), with the size proportional to the inverse variance of the estimate. Diamonds indicate pooled estimates. Lines represent 95% CI. The solid vertical line indicates the null effect. I2 listed below the forest plot. SMD, standardised mean difference.

Sensitivity analyses and publication bias

In the sensitivity analysis, we subsequently omitted each individual study to recalculate the SMDs. The re-evaluated SMDs showed no obvious fluctuation (figure 5). No significant publication bias was detected with Begg’s test (p=0.902) or Egger’s test (p=0.299). The funnel plot showed symmetry on visual inspection (figure 6).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of sensitivity analysis in the meta-analysis.

Figure 6.

Funnel plot for carotid artery stenosis and white matter hyperintensities. SMD, standardised mean difference.

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis showed that the total WMHs were associated with CA stenosis ≥50%. For the first time, our study showed that periventricular WMHs were associated with CA stenosis ≥50%. Although the SMD was small (0.326 and 0.412), the CI was relatively narrow (95% CI 0.194 to 0.459 for the total WMHs and 95% CI 0.202 to 0.622 for periventricular WMHs), which suggested that the effect size is precise.

There were two main potential factors contributing to the weak SMD. First, even though the CA stenosis was set at ≥50%, the stenosis was moderately severe and was not enough to cause very severe WMHs changes. Moreover, most studies do not consider the compensatory function of the circle of Willis (CoW) that redistributes cerebral blood flow after CA stenosis to alleviate the effect of CA on WMHs.23 With the progress of studies, we will further analyse the association between WMHs and CA stenosis ≥70%, and we consider CoW as a confounding factor. Second, WMHs was associated with CA stenosis and SVD.24 The increasing incidence and severity of WMHs with age and hypertension presumably reflects the cumulative effects of both large cerebral arteries, such as CA and SVD. However, only one study on the topic presented data on SVD.8

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis, in which the included studies assessed WMHs using CT or MRI, showed no association between WMHs and CA stenosis.14 The low resolution of CT (compared with MRI) reduced the actual association between WMHs and CA stenosis. The other systematic review also shows no definite correlation between WMHs and CA stenosis. The inclusion criterion of CA in these studies was stenosis ≥30%, which is insufficient for causing the decrease of cerebral blood flow that is partially responsible for WMHs. The meta-analysis could not be performed because of the heterogeneity of the included studies.15

Our meta-analysis also showed that deep WMHs were associated with CA stenosis but with high heterogeneity. The heterogeneity possibly contributed to the different pathogenic mechanisms of periventricular and deep WMHs.25 The periventricular region is supplied by non-collateralising ventriculofugal vessels arising from subependymal arteries. These branches originate either from choroidal arteries or from terminal branches of the striate rami.26 Although these ventriculofugal vessels run towards the penetrating centripetal vessels coming from the pial surface, anastomoses between these two groups of vessels are either scarce or absent.27 Thus, this area is prone to focal or systemic hypoperfusion. In contrast, the subcortical U-fibre region usually escapes involvement in ischaemic WMHs, possibly because this region has a dual blood supply from the subcortical arteries and branches of the medullary arteries.28

Our systematic review and meta-analysis has several limitations. First, grey literature was not searched, and only studies published in English were included. Second, only three (comprising 225 patients) of the eight (comprising 677 patients) included studies reported data on the association between subtypes of WMHs and CA stenosis. However, we should underline that the finding of an association between periventricular WMHs and CA stenosis was identical to that of the total WMHs and CA stenosis. This suggests that the patients included in the three studies actually represent the total population. Third, SMD is small but with no evidence of heterogeneity among studies (figures 2 and 3), indicating that the weak association did not occur by chance. Fourth, as evident in table 2, all studies provide data on age, sex, and whether the patients were symptomatic or asymptomatic, but only one study reported on the status of SVD8 and one study reported on the effect of the CoW.6 This could be an important limitation because these two factors affect WMHs. In addition, our analysis did not investigate the association between WMHs and the different severities of CA stenosis (ie, 50%–69%, 70%–99% and occlusion), which play different roles in the formation of WMHs. The design protocols included patients with CA stenosis with acute ischaemic events in some studies, but without these conditions in other studies. Some studies compared ipsilateral WMHs with stenosed CA versus contralateral, in an intraindividual side-to-side comparison. The other studies compared WMHs in patients with CA stenosis with control subjects with no CA stenosis or stenosis <50%. Finally, the test of publication biases might be underpowered when there were only eight studies in our meta-analysis.29

Conclusions

Our study found an association between the total WMHs and CA stenosis ≥50% and an association between the periventricular WMHs and CA stenosis ≥50%, despite some limitations. The results suggested that WMHs may be considered as an individual risk stratification score for choosing an appropriate therapeutic plan for CA stenosis. Further studies on the topic are necessary, considering that the small SMD made the conclusion less persuasive.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

HY and YW contributed equally.

Contributors: HY and YW have contributed to the design and concept of the manuscript. Others have contributed to writing and revision of the paper. YW: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript drafting. HY: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript drafting. JQ: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data. QW: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. MX: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content. JW: analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, Tanghe HL, et al. Incidental findings on brain MRI in the general population. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1821–8. 10.1056/NEJMoa070972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Smith EE, Saposnik G, Biessels GJ, et al. Prevention of stroke in patients with silent cerebrovascular disease: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2017;48:e44–e71. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341:c3666 10.1136/bmj.c3666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ammirati E, Moroni F, Magnoni M, et al. Relation between characteristics of carotid atherosclerotic plaques and brain white matter hyperintensities in asymptomatic patients. Sci Rep 2017;7:10559 10.1038/s41598-017-11216-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sahin N, Solak A, Genc B, et al. Dilatation of the Virchow-Robin spaces as an indicator of unilateral carotid artery stenosis: correlation with white matter lesions. Acta Radiol 2015;56:852–9. 10.1177/0284185114544243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chuang YM, Huang KL, Chang YJ, et al. Associations between circle of Willis morphology and white matter lesion load in subjects with carotid artery stenosis. Eur Neurol 2011;66:136–44. 10.1159/000329274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Enzinger C, Ropele S, Gattringer T, et al. High-grade internal carotid artery stenosis and chronic brain damage: a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2010;30:540–6. 10.1159/000319025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patankar T, Widjaja E, Chant H, et al. Relationship of deep white matter hyperintensities and cerebral blood flow in severe carotid artery stenosis. Eur J Neurol 2006;13:10–16. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schulz UG, Grüter BE, Briley D, et al. Leukoaraiosis and increased cerebral susceptibility to ischemia: lack of confounding by carotid disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e000261 10.1161/JAHA.113.000261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng HL, Lin CJ, Soong BW, et al. Impairments in cognitive function and brain connectivity in severe asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Stroke 2012;43:2567–73. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.645614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scherr M, Trinka E, Mc Coy M, et al. Cerebral hypoperfusion during carotid artery stenosis can lead to cognitive deficits that may be independent of white matter lesion load. Curr Neurovasc Res 2012;9:193–9. 10.2174/156720212801619009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Streifler JY, Eliasziw M, Benavente OR, et al. Lack of relationship between leukoaraiosis and carotid artery disease. The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Arch Neurol 1995;52:21–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Altaf N, Morgan PS, Moody A, et al. Brain white matter hyperintensities are associated with carotid intraplaque hemorrhage. Radiology 2008;248:202–9. 10.1148/radiol.2481070300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liao SQ, Li JC, Zhang M, et al. The association between leukoaraiosis and carotid atherosclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Neurosci 2015;125:493–500. 10.3109/00207454.2014.949703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baradaran H, Mtui EE, Richardson JE, et al. Hemispheric differences in leukoaraiosis in patients with carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review. Clin Neuroradiol 2017;27:7–13. 10.1007/s00062-015-0402-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wells GA, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2014. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 17. Lin Q, Li Z, Wei R, et al. Increased Risk of Post-Thrombolysis Intracranial Hemorrhage in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients with Leukoaraiosis: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153486 10.1371/journal.pone.0153486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [Internet]. 2009. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org/

- 19. Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu M. Systematic review, meta-analysis design and implementation method. Beijing: People’s medical publishing house, 2016:88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2016;354:i4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saba L, Sanfilippo R, Porcu M, et al. Relationship between white matter hyperintensities volume and the circle of Willis configurations in patients with carotid artery pathology. Eur J Radiol 2017;89:111–6. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2017.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van der Veen PH, Muller M, Vincken KL, et al. Longitudinal relationship between cerebral small-vessel disease and cerebral blood flow: the second manifestations of arterial disease-magnetic resonance study. Stroke 2015;46:1233–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:822–38. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rowbotham GF, Little E. A new concept of the circulation and the circulations of the brain. the discovery of surface arteriovenous shunts. Br J Surg 1965;52:539–42. 10.1002/bjs.1800520714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Reuck J. The human periventricular arterial blood supply and the anatomy of cerebral infarctions. Eur Neurol 1971;5:321–34. 10.1159/000114088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Akashi T, Takahashi S, Mugikura S, et al. Ischemic White Matter Lesions Associated With Medullary Arteries: Classification of MRI Findings Based on the Anatomic Arterial Distributions. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2017;209:W160–8. 10.2214/AJR.16.17231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, et al. Assessing publication bias in meta-analyses in the presence of between-study heterogeneity. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 2010;173:575–91. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2009.00629.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020830supp001.pdf (54.8KB, pdf)