Abstract

Introduction

Frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET) has become an increasingly important part of in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment. Currently, there is still no good scientific evidence to support when to perform FET following a stimulated IVF cycle. Since all published studies are retrospective and the findings are contradictory, a randomised controlled study is needed to provide Level 1 evidence to guide the clinical practice.

Methods/analysis

This is a randomised controlled trial. A total of 724 women undergoing the first FET following ovarian stimulation in IVF will be enrolled and randomised according to a computer-generated randomisation list to either (1) the immediate group in which FET will be performed in the first cycle following the stimulated IVF cycle or (2) the delayed group in which FET will be performed at least in the second cycle following the stimulated IVF cycle. The primary outcome is the ongoing pregnancy defined as a viable pregnancy beyond 12 weeks’ gestation.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been granted by the Ethics Committee of Assisted Reproductive Medicine in Shanghai JiAi Genetics & IVF Institute (JIAI E2017-12) and from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (UW 17–371). A written informed consent will be obtained from each woman before any study procedure is performed, according to good clinical practice. The results of this trial will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

NCT03201783; Pre-results.

Keywords: subfertility, IVF, FET, art

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first randomised controlled trial comparing the ongoing pregnancy rate of immediate versus delayed frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET) following a stimulated in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycle.

This is the first trial that seeks to add significantly to the clinical evidence base and to allow conclusions to be made on the time interval in the FET following a stimulated IVF cycle.

The study includes women aged 20–43 years undergoing the first FET after GnRH agonist and GnRH antagonist ovarian stimulation in IVF/intracytoplasmic sperm injection; thus, results can be extrapolated to the majority of the infertile population.

The researchers, doctors and the participants cannot be blinded to treatment allocation.

The sample size calculation is based on a difference in the ongoing pregnancy rate of 10% between the immediate versus delayed groups as equivalence and may not be able to detect a smaller difference in the ongoing pregnancy rate.

Background

Frozen-thawed embryo transfer (FET) has become an increasingly important part of in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment.1 When women fail to get pregnant after replacing embryos in the stimulated IVF cycle, many of those who have frozen embryos would like to proceed with FET as soon as possible in order to get pregnant as soon as possible.

Ovarian stimulation exerts a detrimental effect on endometrial receptivity.2 Ovarian stimulation leads to supraphysiological hormonal concentrations in blood which may exert negative influence on perinatal and neonatal outcomes.3–5 The freeze-all strategy has drawn attention in recent literature with the advantages of increased maternal safety, improved pregnancy rates, lower ectopic pregnancy rates and better obstetric and neonatal outcomes.6 The better outcomes after elective FET in the context of a freeze-all strategy may be at least partially attributed to the lack of endometrial impairment that is observed during ovarian stimulation.

Robust information regarding the optimal timing for FET following a stimulated IVF cycle is still lacking. One option is to perform FET in the first cycle following the stimulated IVF cycle, that is, immediate transfer. Another option is to postpone FET for at least one menstrual cycle, that is, delayed transfer. Delaying FET may add to the stress and anxiety accompanying the IVF treatment. Several retrospective studies showed similar clinical pregnancy rates or live birth rates between immediate and delayed FET performed following fresh embryo transfers or in a frozen-all policy.7–9 Another retrospective analysis showed that significantly higher implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth rates were found in the delayed FET group than in the immediate group after failed fresh embryo transfer (ET) cycles.10 Since these studies are all retrospective and the findings are contradictory, a randomised study is needed to provide level 1 evidence to guide the clinical practice.

We aim in this randomised trial to compare the ongoing pregnancy rate of immediate versus delayed FET following a stimulated IVF cycle. The hypothesis is that the ongoing pregnancy rates of immediate and delayed FET are comparable.

Materials and methods

Study design

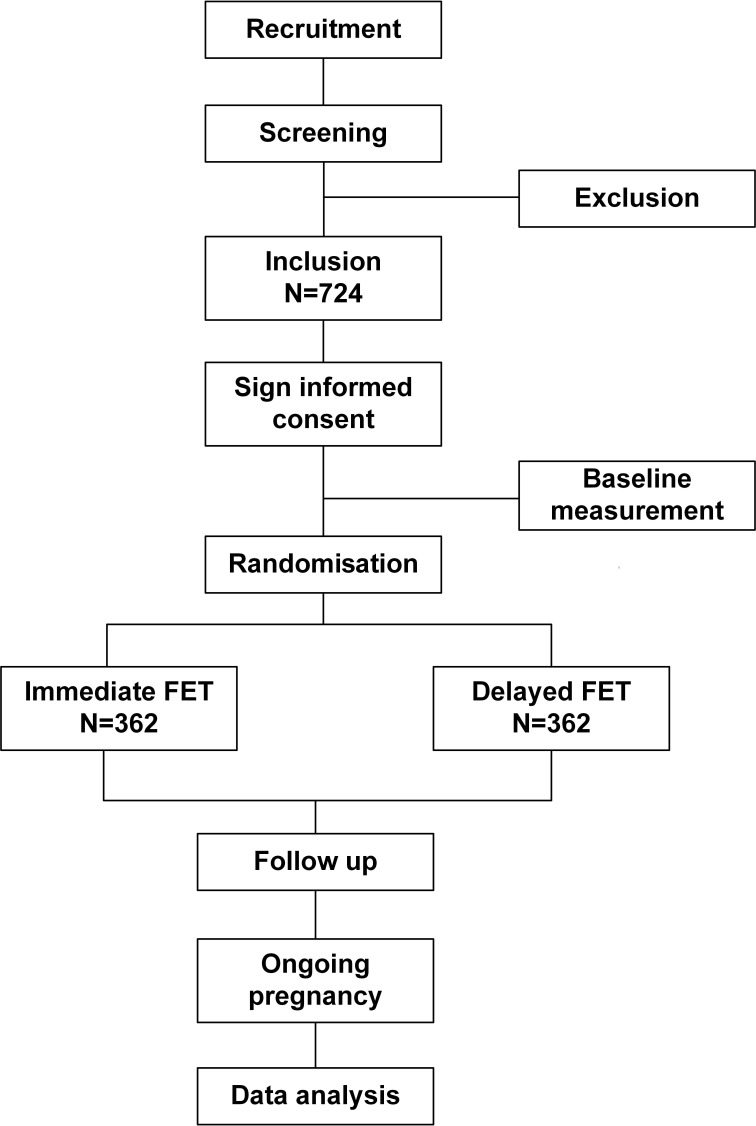

This is a two-centre randomised controlled study carried out in the Shanghai JiAi Genetics & IVF Institute and Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the University of Hong Kong. The flow chart of this study is shown in figure 1, and the overview of the study visits is shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

The study flow chart. FET, frozen-thawed embryo transfer.

Table 1.

Overview of study visits

| Screen and baseline visit | Treatment visit | Pregnancy visit | Follow-up visit | |

| Physical examination (weight, height) | √ | |||

| Menstrual cycle | √ | |||

| Fasting blood samples for E2, P | √ | |||

| Preconception counselling | √ | |||

| Questionnaire | √ | √ | ||

| Transvaginal ultrasound | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Pregnancy test | √ | √ | ||

| Pregnancy and neonatal records | √ |

E2, oestradiol; P, progesterone.

Participants

The study participants will consist of women and their partners initiating IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) treatment at the Shanghai JiAi Genetics & IVF Institute in China and Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, the University of Hong Kong. Recruitment will be carried out by the doctors at the fertility clinics. Eligible women will be recruited if they fulfil all of the inclusion criteria and do not meet any of the exclusion criteria. They will be included once for this study. After detailed explanation, counselling and signing the informed consent form, the eligible participants will be randomly allocated to either the immediate group or the delayed group.

Inclusion criteria

Women aged ≤43 years at the time of IVF/ICSI treatment.

Undergoing IVF with a standard stimulation.

At least one frozen embryo or blastocyst.

The first FET cycle following ovarian stimulation in IVF/ICSI.

Exclusion criteria

Use of mild stimulation or natural cycle for IVF/ICSI treatment.

Severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome during IVF/ICSI treatment.

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis treatment.

Use of donor oocytes.

Presence of hydrosalpinx which is not surgically treated or endometrial polyp on scanning during ovarian stimulation.

Standard and mild stimulation is defined according to the published terminology for ovarian stimulation for IVF.11 Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) is diagnosed and classified according to the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guideline.12

Randomisation

Women having the first FET cycle after a failed stimulated IVF cycle or undertaking the freeze-all strategy will be randomised according to a computer-generated randomisation list into one of the following two groups. The exact timing of randomisation is on the day of embryo freezing for patients taking the freeze-all strategy and on the day of blood hCG test 14 days after fresh-ET for the failed fresh-ET women. The randomisation is carried out by a project nurse who is not involved in the recruitment and clinical management of patients using an online randomisation program through the website www.randomization.com. Then the nurse will prepare the randomisation arm and put it into opaque envelopes for use. On the randomisation day, the recruited women will be randomised according to the opaque envelopes into one of the two groups:

The immediate group in which FET will be performed in the first cycle following the stimulated IVF cycle.

The delayed group in which FET will be performed at least in the second cycle following the stimulated IVF cycle.

Blinding

Both the researchers and the participants cannot be blinded because of the nature of the study. The embryologist performing the quality assessment is blinded to the allocated treatment.

Interventions

Women will undergo IVF/ICSI treatment in the centre as clinically indicated. Standard ovarian stimulation with gonadotrophins in either a GnRH antagonist protocol or long GnRH agonist protocol will be employed. Oocyte retrieval will be performed under transvaginal ultrasound guidance 34–36 hours after triggering with hCG or an agonist. Oocytes will be fertilised using either conventional insemination or ICSI depending on the semen quality of the husbands in accordance with the standard protocol. Normal fertilisation will be assessed and confirmed by the presence of two pronuclei and a second polar body at 16–18 hours after insemination or ICSI. On day 3 after oocyte retrieval, an embryo with at least seven blastomeres and grades 1 and 2 is defined as good quality. Embryos with at least six blastomeres and fragments <50% will be frozen. All good embryos will be frozen or vitrified using the Crytop method as cleavage stage embryos on day 3 or as full to expanded blastocysts on day 5 or day 6 of embryo culture according to the standard protocol. Patients who have ≥6 good-quality embryos on day 3 will be counselled for extended culture and blastocyst transfer.

We will measure the stress and anxiety levels by the standard questionnaire before the randomisation and at the time of starting FET. The Chinese State-Trait Anxiety Inventory was used to measure the patient’s anxiety level.13

Hormone replacement treatment (HRT) will be used for endometrial preparation. On day 3 of the menstrual cycle, estradiol valerate (E2, Progynova, Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) will be commenced 4 mg daily for 10 days. When the thickness of the endometrial layer reaches at least 8 mm on pelvic scanning, vaginal progesterone 90 mg per day (Crinone, Merck-Serono, Switzerland) will be administered. For day 3 embryos, FET is scheduled on the fourth day of starting vaginal progesterone. For blastocysts, FET is scheduled on the sixth day of starting vaginal progesterone. A maximum of 1–2 embryos or blastocysts with the best morphology will be transferred under ultrasound guidance using a soft embryo-transfer catheter. Serum hCG level will be checked 14 days after FET. All hormone therapy will be stopped if the serum hCG level is negative. All pregnant women will continue the hormonal therapy until 12 weeks of gestation.

Follow-up and data collection

If the serum hCG level is positive, transvaginal ultrasound will be performed 2 weeks later to locate the pregnancy and confirm fetal viability. Subsequent management will be the same as other women with early pregnancy. They will be referred for antenatal care when the ongoing pregnancy is 12 weeks.

Written consent regarding retrieval of pregnancy and delivery data will be sought from the patient at the time of the study. The patient will be contacted after delivery by phone to retrieve the information of the pregnancy outcomes. The outcomes of the pregnancy (delivery, miscarriage), number of babies born, birth weights and obstetrics complications will be recorded.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is an ongoing pregnancy defined as a viable pregnancy beyond 12 weeks’ gestation.

Secondary outcomes

Positive hCG level: conception is defined with the result of serum β-hCG ≥10 mIU/mL.

Clinical pregnancy is defined as presence of intrauterine gestational sac by transvaginal ultrasound at 6 gestational weeks.

Implantation rate as the number of gestational sacs per embryo transferred.

Multiple pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage rates. Miscarriage rate is defined as a clinically recognised pregnancy loss before 22 weeks of pregnancy. The denominator is the clinical pregnancy.

A live birth is defined as the delivery of any number of newborns ≥22 weeks’ gestation with heartbeat and breath.

Birth weight of newborns.

Data entry and quality control of data

Treatment-related data including baseline information and controlledovarianhyperstimulation(COH) data are collected at the day of embryo frozen. Data on FET cycle are collected at frozen embryo transfer day. Follow-up data on all pregnancies resulting from FET according to the study protocol will be followed from study inclusion and 1 year onwards. Participants information forms will be developed for data entry, and quality control of the data will be handled at two different levels. The investigators will be required to ensure the accuracy of the data as the first level of control, and the second level will include data monitoring and validation that will be carried out on a regular basis throughout the study. Data are backed up daily to another computer in the same physical location as the server.

Sample size calculations and statistical analysis

Sample size estimation

According to our data of the centre, the ongoing pregnancy rate per FET was about 30%. We hypothesise that a difference in the ongoing pregnancy rate of 10% between the immediate versus delayed groups as equivalence, the sample size required for a test of equivalence would be 329 in each arm to give a power of 0.8 and type I error of 0.05. Allowing 10% drop-out, 724 subjects or 362 in each arm will be needed.

Data analysis

Data will be analysed with an intention to treat and per protocol. Demographic features of the two groups will be compared. Comparison of quantitative variables will be performed using Student’s t-test, while categorical variables will be compared using a χ2 analysis. If randomisation fails to achieve two balanced groups, we will use the multivariable logistic regression to adjust for potentially confounding factors and results, namely female age (as a continuous variable), failed fresh ET or freeze-all, retrieved oocytes, COH protocol, ovulation trigger, number of good-quality embryos produced (as a continuous variable) and number of embryos transferred (one vs two), developmental stage (cleavage vs blastocyst stage) and quality of the embryos transferred (quality of the embryo transferred). If the primary unadjusted analysis and secondary adjusted analysis are discordant, we will give greater weighting to the primary analysis in the interpretation of trial findings.

All statistical analyses of the data will be performed using the SPSS program V.21.0 (SPSS), and a p value <0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

The research question about the optimal timing for FET following a stimulated IVF cycle was first proposed by patients who failed fresh ET or in freeze-all policy. Patients were not involved in the design and conduct of the study. The results will be disseminated to study participants by their physician.

Ethics and dissemination

Since FET in HRT cycles is a standard procedure in IVF centres, and there is no agreement regarding the time interval between the stimulated IVF and the subsequent FET in the literature, there are not predefined criteria for premature termination of the study. There is no interim analysis during the study.

The women who agree to participate in the study will sign a consent form (see online supplementary appendix 1) after detailed counselling of the study, and they are free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving any reason and having any impact on the medical care they are receiving.

bmjopen-2017-020507supp001.pdf (118.8KB, pdf)

Data will be entered electronically and all data will be stored in locked computer files that are accessible only to the investigators and research staff involved in the study. Original study forms will be kept locked at the study site and maintained in storage for a period of 3 years after the completion of the study. The principal investigator will be responsible for data management including data coding, monitoring and verification. The investigators have always maintained a strict privacy policy. The investigators permit trial-related monitoring, audits, Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee (IRB/IEC)IRB/IEC review and regulatory inspections, providing direct access to source data/documents. For questions about the study, the participants should contact their physician.

A data and safety monitoring committee will review and interpret the data generated from the study, and its primary objectives will be to ensure the safety of the study participants and the integrity of the research data. The committee consists of two independent researchers with experience in reproductive medicine.

An audit trail will be designed as another security measure to preserve the integrity of the trial. Computer-generated and time-stamped audit trails will be implemented for tracking changes in the electronic source documentation. Internal safeguards will be built into the computerised system. Records will be regularly backed up, and record logs will be maintained to prevent data loss and to ensure the data’s quality and integrity.

Amendments to the protocol will be agreed on by the IRB/IEC, data and safety monitoring committee and will be approved by the ethics committee prior to implementation.

The results of this trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications and presentations at international scientific meetings.

Trial status

The study was designed in May 2017, and the first participant was randomised on 9 August 2017. At the time of the manuscript preparation, we have recruited 200 women and the recruitment is ongoing. Trail registration number: NCT03201783 and stage: pre-results.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HL, XS and EHYN conceived and designed the study. HL and EHYN drafted and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. XS sought ethical approval. LL and XL participated in the coordination of the study and recruitment of subjects. All the authors contributed to the further writing of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of Assisted Reproductive Medicine in Shanghai JiAi Genetics & IVF Institute (JIAI E2017-12) and Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster (UW 17-371).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Doody KJ. Cryopreservation and delayed embryo transfer-assisted reproductive technology registry and reporting implications. Fertil Steril 2014;102:27–31. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shapiro BS, Daneshmand ST, Garner FC, et al. Evidence of impaired endometrial receptivity after ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization: a prospective randomized trial comparing fresh and frozen-thawed embryo transfer in normal responders. Fertil Steril 2011;96:344–8. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Venetis CA, Kolibianakis EM, Bosdou JK, et al. Estimating the net effect of progesterone elevation on the day of hCG on live birth rates after IVF: a cohort analysis of 3296 IVF cycles. Hum Reprod 2015;30:684–91. 10.1093/humrep/deu362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weinerman R, Mainigi M. Why we should transfer frozen instead of fresh embryos: the translational rationale. Fertil Steril 2014;102:10–18. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.05.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roque M, Valle M, Guimarães F, et al. Freeze-all policy: fresh vs. frozen-thawed embryo transfer. Fertil Steril 2015;103:1190–3. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blockeel C, Drakopoulos P, Santos-Ribeiro S, et al. A fresh look at the freeze-all protocol: a SWOT analysis. Hum Reprod 2016;31:491–7. 10.1093/humrep/dev339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santos-Ribeiro S, Polyzos NP, Lan VT, et al. The effect of an immediate frozen embryo transfer following a freeze-all protocol: a retrospective analysis from two centres. Hum Reprod 2016;31:2541–8. 10.1093/humrep/dew194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santos-Ribeiro S, Siffain J, Polyzos NP, et al. To delay or not to delay a frozen embryo transfer after a failed fresh embryo transfer attempt? Fertil Steril 2016;105:1202–7. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.12.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lattes K, Checa MA, Vassena R, et al. There is no evidence that the time from egg retrieval to embryo transfer affects live birth rates in a freeze-all strategy. Hum Reprod 2017;32:368–74. 10.1093/humrep/dew306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Volodarsky-Perel A, Eldar-Geva T, Holzer HE, et al. Cryopreserved embryo transfer: adjacent or non-adjacent to failed fresh long GnRH-agonist protocol IVF cycle. Reprod Biomed Online 2017;34:267–73. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nargund G, Fauser BC, Macklon NS, et al. The ISMAAR proposal on terminology for ovarian stimulation for IVF. Hum Reprod 2007;22:2801–4. 10.1093/humrep/dem285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Green-top guideline No.5. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg5/ (accessed 26 Feb 2015).

- 13. Shek DTL. The factorial structure of the Chinese version of the state-trait anxiety inventory: a confirmatory factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas 1991;51:985–97. 10.1177/001316449105100418 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020507supp001.pdf (118.8KB, pdf)