Abstract

Introduction

Return to work (RTW) after breast cancer (BC) is still a new field of research. The factors determining shorter sick leave duration of patients with BC have not been clearly identified. The aim of this study was to describe work during BC treatment and to identify factors associated with sick leave duration.

Materials and methods

An observational, prospective, multicentre study was conducted among women with operable BC. A logbook was given to all working patients to record sociodemographic and work-related data over a 1-year period.

Results

Work-related data after BC were available for 178 patients (60%). The median age at diagnosis was 50 years (27–77), 87.9% of patients had an invasive form of BC and 25.3% a lymph node involvement. 25.9% had a radical surgery and 24.2% had an axillary dissection. Radiotherapy was performed in 90.9% of patients and chemotherapy in 48.1%. Sick leave was prescribed for 165 patients (92.7%) for a median of 155 days. On univariate analysis, invasive BC (p=0.025), lymph node involvement (p=0.005), radical surgery (p=0.025), axillary dissection (p=0.004), chemotherapy (p<0.001), personal income <€1900/month (p=0.03) and not having received the patient information booklet on RTW (p=0.047) were found to be associated with a longer duration of sick leave. On multivariate analysis, chemotherapy was found to be associated with longer sick leave (OR: 3.5; 95% CI 1.6 to 7.9; p=0.002). The cost of sick leave to French National Health Insurance was fourfold higher in the case of chemotherapy (p<0.001).

Conclusion

Advanced disease and chemotherapy are major factors that influence sick leave duration during the management of BC.

Trial registration number

Keywords: breast tumours, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective multicentric study.

Description of factors associated with long sick leave.

Multimodal analysis including evaluation of costs of sick leave.

Few qualitative information.

Introduction

Improvements in early detection and treatment have resulted in an increasing number of breast cancer (BC) survivors.1 Treatments mostly focus on curing the disease and preventing metastatic relapse. About one-third of women diagnosed with BC are under the age of 55 with a 10-year survival close to 80%.2 Many patients therefore recover and resume their activities of daily living during or after treatment. Return to work (RTW) is an event at the end of sick leave, consisting in resuming professional activity. RTW after BC is still a new but important aspect of survivorship research, not only from a societal point of view, as it provides financial resources for rehabilitation of cancer survivors and contributes to psychosocial well-being, including physical and mental health.3 Some BC cancer survivors experience reduced work ability.4–8 Difficulties at work or unemployment differ according to the type of BC treatment. Cancer treatment varies according to the stage of the disease and can include surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormone therapy. For many patients with cancer, RTW helps them to recover from treatment and also constitutes a positive step towards the future. The identification of factors that maintain patients at work during and after BC treatment could help healthcare professionals to more accurately identify patients at risk of RTW-related difficulties in order to provide them with adapted support during BC management. The aim of this prospective study was to describe work during and after BC management and identify factors associated with either cessation or maintenance at work.

Materials and methods

OPTISOINS01 was an observational, prospective, multicentre study conducted from December 2014 to March 2016 among patients with BC from a regional health territory. The primary objective of the Optisoins01 study was to identify the main care pathway after 1 year of early BC and to evaluate costs from various perspectives. RTW evaluation was one of the secondary objectives of the study. The Optisoins01 study design has been previously described.9 Eight non-profit hospitals participated in the study: three teaching hospitals, four general hospitals and one comprehensive cancer centre. Inclusion criteria were: women aged ≥18 years with previously untreated, first, histologically confirmed, operable BC. Exclusion criteria were: metastatic, locally advanced or inflammatory BC and previous history of BC.

After BC diagnosis, a work and cancer information booklet had to be given to all working patients. Our Institute has designed an information booklet in collaboration with occupational physicians and the Paris Regional Health Insurance (Caisse Régionale d’Assurance Maladie d’Île-de-France). This document includes the testimonies from employees, advice and practical information to help patients anticipate difficulties and find support: possibility of part-time work, career development plan, roles of occupational physicians and general practitioners. The booklet is freely available online with the support of the ‘ARC’ Foundation.10

After inclusion, all patients were given a logbook in which to record, throughout the year, sociodemographic data (age, marital status, type of occupation, personal income and so on), out-of-pocket health expenses and a 1-year occupational questionnaire for employed women including dates of work and absence from work during treatments, job adjustments, on-shift status and the perceived quality of reintegration with standardised self-questionnaire (income change, difficulties at work with co-workers and/or with superiors and so on). Patients were asked to fill in the questionnaire prospectively during the all study period. During the second half of the year, clinical research assistants made two phone calls to remind patients to fill in the logbook. Questionnaires were collected at the end of the study. Types of occupations were classified according to the French Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (INSEE) classification.

Two groups of patients were compared in order to determine the factors associated with sick leave duration: longer sick leave (longer or equal to the median duration) and shorter sick leave (shorter than the median duration). Fisher’s exact test or Student’s t-test were used to analyse these factors. These tests were two sided with a 0.05 level of significance. Multivariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression model. We considered adjusted p value for multiple comparisons. Sick leave over a 1-year period was described according to whether or not the patients were treated by chemotherapy. Differences in the areas under the curves of the two populations were compared with 1000 permutations of random allocation of chemotherapy. The same analysis was performed according to whether or not the patients had received the work information booklet. Differences were considered significant for p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with R software.11

The cost of sick leave for National Health Insurance was calculated on the basis of the monthly income declared by the patients, the duration of sick leave and the national sick leave allowance scale.

This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02813317) and was approved by the French National ethics committee (CCTIRS Authorisation No. 14.602 and CNIL DR-2014–167) covering research at all participating hospitals.

Patient and public Involvement: A sample of patients participated in the questionnaire development concerning work activity before implementation of the study. Patients were involved in the study by actively completing the questionnaires during 1 year. A results-report will be sent to the study participants.

Results

Six hundred and four patients with a median age of 58 years (range: 24–98) were included in the Optisoins01 study, including 297 patients (48.2%) who were working at the time of BC diagnosis. The present study focused on these 297 patients.

Detailed patient characteristics and cancer characteristics are presented in table 1. The median age of the women was 50 (range: 27–77) years, 54 women (18.2%) were single, 153 (51.5%) were married, 39 (13.1%) were divorced and 3 (1.0%) were widows. Two hundred and sixty-one patients (87.9%) had invasive BC and 35 (11.8%) had in situ BC. Seventy-five women (25.3%) presented with axillary lymph node involvement.

Table 1.

Patient and cancer characteristics and breast cancer treatments (n=297)

| n or Median | % or Range | |

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 50 | 27–77 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 54 | 18.2 |

| Married | 153 | 51.5 |

| Divorced | 39 | 13.1 |

| Widow | 3 | 1 |

| NA | 48 | 16.2 |

| Breast cancer characteristics | ||

| Modes of diagnosis | ||

| Organised screening | 60 | 20.2 |

| Individual screening | 114 | 38.4 |

| Clinical signs | 123 | 41.4 |

| Type of cancer | ||

| Invasive | 261 | 87.9 |

| In situ | 35 | 11.8 |

| NA | 1 | 0.3 |

| Lymph node involvement | ||

| Yes | 75 | 25.3 |

| No | 222 | 74.7 |

| Surgery | ||

| Breast surgery | ||

| Conservative | 220 | 74.1 |

| Radical | 77 | 25.9 |

| Lymph node surgery | ||

| Sentinel lymph node procedure | 203 | 68.4 |

| Axillary dissection | 72 | 24.2 |

| NA | 22 | 7.4 |

| Surgical revision | ||

| No | 227 | 76.4 |

| 1 | 60 | 20.2 |

| >1 | 10 | 3.4 |

| Type of hospitalisation | ||

| Outpatient surgery | 107 | 36 |

| Conventional surgery | 190 | 64 |

| Adjuvant therapies | ||

| Radiotherapy | ||

| No | 27 | 9.1 |

| Yes | 270 | 90.9 |

| Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 143 | 48.1 |

| No | 154 | 51.9 |

| Trastuzumab | ||

| Yes | 36 | 12.1 |

| No | 100 | 33.7 |

| NA | 161 | 54.2 |

| Hormone therapy | ||

| Yes | 220 | 74.1 |

| No | 77 | 25.9 |

Two hundred and twenty women (74.1%) underwent breast-conserving surgery and 77 (25.9%) underwent radical mastectomy (table 1). A sentinel lymph node procedure was performed for 203 patients (68.4%). Seventy patients required at least one reoperation for the following reasons: positive surgical margins and secondary mastectomy, sentinel lymph node procedure following discovery of an invasive tumour, axillary dissection following positive sentinel lymph node biopsy and surgical complications (abscess, haematoma and so on). After surgery, 90.9% of patients received radiotherapy 48.1% of patients received adjuvant chemotherapy and 74.1% of patients received hormone therapy.

Most patients were executives (31.4%) or employees (33.3%). Most patients (47.1%) had a monthly income >€1900. Work data after BC were available for 178 patients (60%, online supplemental figure 1). Patients who did not complete the 1work questionnaire in the logbook during 1 year were globally less compliant with the study and less medicalised (online supplemental table 1). Sick leave was prescribed for 165 patients (92.7%). Patients had only one sick leave in 52.2% of cases, two sick leaves in 21.9% of cases and three or more sick leaves in 18.5% of cases. Median duration of sick leave was 155 days (range: 5–365). After treatment, seven patients (3.9%) lost their jobs and 46.1% had reduced income. Patients encountered difficulties with their coworkers in 3.4% of cases, with their superiors in 3.9% of cases and for undocumented reasons in 12.9% of cases. Work-related factors are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Work characteristics before and after BC

| n or Median | % or Range | |

| Work characteristics before BC, n=297 | ||

| Type of occupation | ||

| Farmer | 1 | 0.3 |

| Self-employed | 8 | 2.5 |

| Executive | 99 | 31.4 |

| Employee | 105 | 33.3 |

| Intermediate profession | 29 | 9.2 |

| Blue-collar worker | 2 | 0.6 |

| NA | 53 | 22.9 |

| Personal income per month (€) | ||

| No income | 6 | 2 |

| <1900 | 104 | 35 |

| >1900 | 140 | 47.1 |

| NA | 47 | 15.8 |

| Work characteristics after BC, n=178 | ||

| Dismissal | 7 | 3.9 |

| Income change | ||

| Decreased | 82 | 46.1 |

| Increased | 3 | 1.7 |

| Stable | 73 | 41 |

| NA | 20 | 11.2 |

| Decreased income (%), n=82 | ||

| <10 | 37 | 45.1 |

| 10–30 | 13 | 15.8 |

| 30–60 | 5 | 6.1 |

| >60 | 3 | 3.7 |

| NA | 24 | 29.3 |

| Sick leave | ||

| Yes | 165 | 92.7 |

| No | 13 | 7.3 |

| Number of sick leaves (n=165) | ||

| 1 | 93 | 52.2 |

| 2 | 39 | 21.9 |

| >2 | 33 | 18.5 |

| Duration of sick leave (days) | 155 | 5–365 |

| Difficulties at work (n=36) | ||

| With coworkers | 6 | 3.4 |

| With superiors | 7 | 3.9 |

| Other | 23 | 12.9 |

BC, breast cancer.

bmjopen-2017-020276supp001.jpg (214.9KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-020276supp002.pdf (36.5KB, pdf)

On univariate analysis, the presence of clinical signs leading to a diagnosis of BC (p<0.001), an invasive form of BC (p=0.02), lymph node involvement (p=0.005), radical surgery (p=0.02), axillary dissection (p<0.001), chemotherapy (p<0.001), personal income <€1900/month (p=0.03) and not having received the work and cancer information booklet (p=0.047) were associated with a longer total duration of sick leave (table 3). Moreover, patients with longer sick leave were more likely to have reduced income after treatment of their disease (p=0.0012).

Table 3.

Determinants and consequences of long sick leave

| Sick leave <155 days, n=79 | Sick leave ≥155, days n=77 | P values | |||

| n or Median | % or Range | n or Median | % or Range | ||

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 50.6 | 27–59 | 50 | 29–77 | 0.52 |

| Type of occupation | 0.09 | ||||

| Farmer | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Self-employed | 3 | 3.8 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Executive | 36 | 45.6 | 29 | 37.7 | |

| Employee | 25 | 31.6 | 38 | 49.4 | |

| Intermediate profession | 13 | 16.5 | 7 | 9.1 | |

| Blue-collar worker | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| NA | 1 | 1.3 | 2 | ||

| Personal income per month (€) | 0.03 | ||||

| <1900 | 25 | 31.6 | 37 | 48.1 | |

| >1900 | 54 | 68.4 | 38 | 49.4 | |

| NA | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Marital status | 0.76 | ||||

| Single | 18 | 22.8 | 12 | 15.6 | |

| Married | 47 | 59.5 | 49 | 63.6 | |

| Divorced | 12 | 15.2 | 14 | 18.2 | |

| Widow | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| NA | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Breast cancer characteristics | |||||

| Type of cancer | <0.001 | ||||

| Invasive | 63 | 79.7 | 74 | 96.1 | |

| In situ | 16 | 20.3 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| Lymph node involvement | 0.005 | ||||

| Yes | 11 | 13.9 | 26 | 33.8 | |

| No | 68 | 86.1 | 52 | 67.5 | |

| Surgery | |||||

| Breast surgery | 0.02 | ||||

| Conservative | 66 | 83.5 | 50 | 64.9 | |

| Radical | 13 | 16.5 | 27 | 35.1 | |

| Lymph node surgery | <0.001 | ||||

| Sentinel lymph node procedure | 62 | 78.5 | 48 | 62.3 | |

| Axillary dissection | 9 | 11.4 | 26 | 33.8 | |

| NA | 8 | 10.1 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| Surgical revision | 0.06 | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 16.5 | 23 | 29.9 | |

| No | 66 | 83.5 | 54 | 70.1 | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.53 | ||||

| Yes | 72 | 91.1 | 74 | 96.1 | |

| No | 7 | 8.9 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| Chemotherapy | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 25 | 31.6 | 56 | 72.7 | |

| No | 54 | 68.4 | 21 | 27.3 | |

| Trastuzumab | 0.54 | ||||

| Yes | 9 | 11.4 | 12 | 15.6 | |

| No | 16 | 20.3 | 40 | 51.9 | |

| NA | 54 | 68.4 | 25 | 32.5 | |

| Hormone therapy | 0.05 | ||||

| Yes | 50 | 63.3 | 61 | 79.2 | |

| No | 29 | 36.7 | 16 | 20.8 | |

| Patient management | |||||

| Modes of diagnosis | <0.001 | ||||

| Organised screening | 15 | 19 | 21 | 27.3 | |

| Individual screening | 43 | 54.4 | 20 | 26 | |

| Clinical signs | 21 | 26.6 | 36 | 46.8 | |

| Type of hospitalisation | <0.001 | ||||

| Outpatient surgery | 58 | 73.4 | 34 | 44.2 | |

| Inpatient surgery | 21 | 26.6 | 43 | 55.8 | |

| Work and cancer information booklet | |||||

| Yes | 64 | 81 | 52 | 67.5 | 0.047 |

| No | 15 | 19 | 25 | 32.5 | |

| Return to work | |||||

| Dismissal 1 | 1.3 | 3 | 3.9 | 0.62 | |

| Income change | |||||

| Decreased | 23 | 29.1 | 48 | 62.3 | <0.001 |

| Increased | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.6 | |

| Stable | 37 | 46.8 | 24 | 31.2 | |

| NA | 19 | 24.1 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| Decreased income (%) | 0.61 | ||||

| <10 | 11 | 13.9 | 21 | 27.3 | |

| 10–30 | 4 | 5.1 | 7 | 9.1 | |

| 30–60 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5.2 | |

| >60% | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3.9 | |

| NA | 64 | 81 | 42 | 54.5 | |

| Difficulties at work | |||||

| With coworkers | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 3.9 | 0.67 |

| With superiors | 0 | 0 | 6 | 7.8 | 0.17 |

| Other | 7 | 8.9 | 14 | 18.2 | 0.93 |

Bold values means p<0.05 (statistically significant).

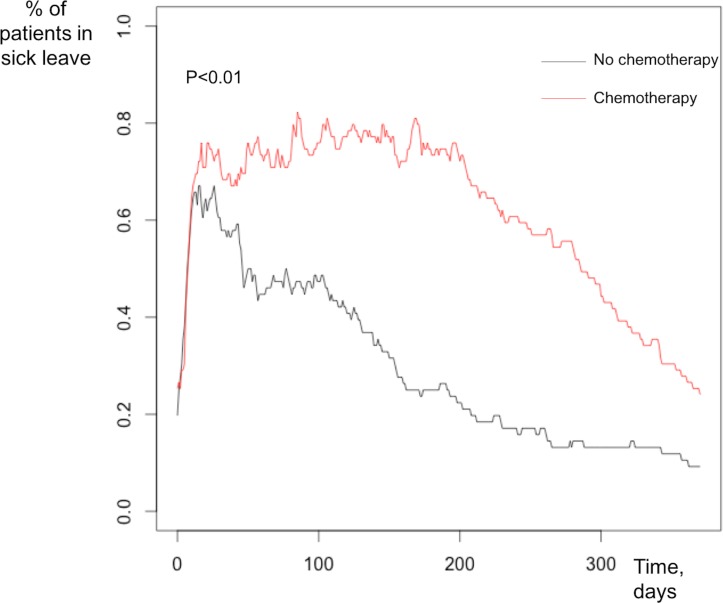

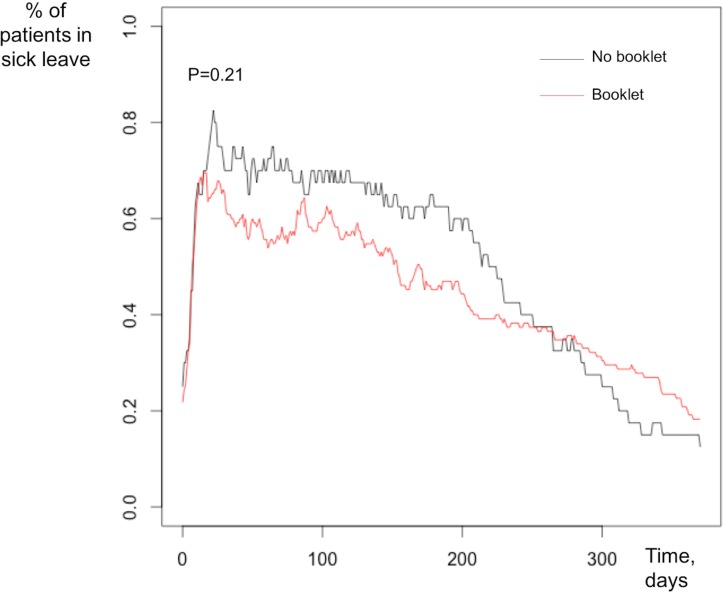

On multivariate analysis, chemotherapy was the only independent factor associated with longer sick leave (OR: 3.5, 95% CI 1.6 to 7.9, p=0.002). Patients treated by chemotherapy had longer sick leave than those not treated by chemotherapy (figure 1). The difference in terms of the 1-year distribution of sick leave was not statistically significant between patients according to whether or not they had received the work information booklet (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients on sick leave at 1-year follow-up depending on the presence or absence of chemotherapy.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients on sick leave at 1-year follow-up depending on whether or not they had been given the work information booklet.

Considering the working population of OPTISOINS01 study with complete data on sick leave and salary, the median cost of sick leave for National Health Insurance was €8841 per patient per year from diagnosis. On performing univariate and multivariate analyses, the only determinant of sick leave costs found in this study was the administration of chemotherapy, with a fourfold higher median allowance for patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy.

Discussion

Although many BC cancer survivors are able to return to a normal work life after treatment, our study confirms that many women of working ages do not. Sick leave is frequently prescribed and is often long, with a median sick leave of 155 days in this study.

Factors associated with long sick leave (>155 days) were severe or advanced forms of BC. The duration of sick leave was also associated with the mode of diagnosis, as patients diagnosed by breast screening presented shorter sick leaves. Public health authorities should therefore promote breast screening in order to decrease the proportion of advanced forms of BC and aggressive therapies with severe consequences on work and personal activities. Consequently, longer sick leave was also associated with more aggressive therapy, such as radical surgery, axillary dissection and chemotherapy. These results are similar to those published in the literature.4 7 8 12 13 Chemotherapy is an aggressive treatment that can be necessary in order to improve survival, but which has long-lasting consequences in terms of self-esteem (alopaecia…), chronic pain (neuropathy…) and chronic fatigue, that play an important role in RTW and maintenance at work.6 BC survivors may have to deal with the side effects specific to this type of treatment. Although many side effects of chemotherapy are only temporary,14 some studies have shown that chemotherapy may impact on cognitive functioning15 and fatigue16 up to 10 years after diagnosis. Cognitive functioning and fatigue have both been associated with impaired work functioning.17 Munir et al 18 reported that up to 62%–84% of women resumed work either during treatment with chemotherapy or following completion of treatment. As a result of their cognitive limitations, women reported that they experienced difficulties with their work ability, particularly difficulties doing multiple tasks, reduced clarity of decisions, deficits in clear thinking and feelings of being inept due to short-term memory.19 Rapid progress is being made in the field of chemotherapy with the routine use of new genomic signature tests that allow more accurate targeting of patient likely to benefit from chemotherapy. According to Nesvold et al 20 and Eaker et al 14 mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection may influence working life long after treatment due to an increased risk of chronic pain. BC survivors are more likely to suffer from upper extremity impairments or lymphoedema than are other cancer survivors,21–24 which are responsible for difficulties at returning to work.25 26

The work and cancer information booklet appeared to help patients RTW with significantly shorter sick leave in univariate analysis, but not in the multivariate analysis. However, this suggests that an action, such as an active support, could help to reduce sick leave duration. The information booklet advises women to attend the occupational medicine service. In France, occupational medicine plays an essential role, but the patient is not obliged to consult the occupational physician when sick leave is <3 months. However, at 3 months, the occupational physician and the employee must determine the modalities of RTW, based on the employee’s state of health and the characteristics of the workplace. These arrangements concern the employee himself and the work collective with, if necessary, actions so that the reception is assured to the return. Setting up of a schedule, reduction of working hours, modification of physical, mental or workplace loads can also be instituted at the time of RTW. The occupational physician can provide recommendations to the employer, unless the employer refuses. The results obtained with this handbook are particularly encouraging and suggest that more individual supports should be developed. Health coaching by telephone and/or face-to-face interview have already been tested,27–29 showing positive significant outcomes on physical activity, body mass index, pain management, acceptance of disease and self-confidence among cancer survivors. Coaching methods have never been tested in the management of working patients during cancer treatmentmaintenance. Our Institute is therefore setting up a prospective randomised study (OPTICOACH) with tailored support intervention to enhance RTW after BC in collaboration with a professional coach, consisting of individual interviews or small group workshops over a period of 3 years.

Difficulties at returning to work appear to extend over a period of many years. Sevellec et al 28 showed that 6 years after returning to work, one employee out of two was still working in the same company. Rather than disappearing, the difficulties identified many years after BC persist for a long time after stopping treatment. It is therefore essential to identify the factors associated with longer sick leave and RTW difficulties in order to help working patients and prevent these long-term problems. The VICAN 2 study29 focused on the factors associated with difficulties at RTW. This large study was carried out in 2014 by the French National Cancer Institute, on the living conditions of people with cancer (not only BC), 2 years after the diagnosis. The people most vulnerable to job loss 2 years after the cancer diagnosis are mainly those working in the so-called socioprofessional execution categories, the youngest and oldest, married people with a level of education below the baccalaureate level and those with precarious contracts.

One of the potential biases of this study concerns the characteristics of the study population, as almost the majority of women belonged to the wealthiest social classes, as 45.6% of patients were executives and only 1.3% were blue-collar workers. More than 68% of patients had a personal monthly income >€1900 and 36.7% had a personal monthly income >€2600. This distribution does not exactly reflect French society; in France, according to the INSEE statistics of 2014, the median monthly income was €1772. Similarly to our results, a Canadian team30 has shown that women with an annual income <C$20 000 were less likely to RTW than those whose income exceeded C$50 000. The French social protection system also plays a role, as it provides cancer survivors with the possibility of replacement income, allowing women to decide whether or not they wish to RTW immediately. Providing assistance and support to all working patients should therefore be a priority.

Conclusion

Advanced disease and chemotherapy are major factors that influence RTW with longer sick leave. Systematic screening or use of innovative tools, such as genomic signatures, can facilitate earlier diagnosis and reduce aggressive therapies.

Depending on the type of treatment, stage of the disease and type of occupation, information and coaching methods with the occupational medicine service should systematically be given to working women, helping them to anticipate job adjustments with flexibility of work schedule for example.

Personalised coaching methods have been successfully used to promote acceptance of disease and self-confidence and should be tested in the management of RTW.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: DH, RR and SB designed the study. BA and SN contributed to the design and implementation of the research. SB and A-LS performed the health economic analysis. AA and DH performed all the remaining statistical analysis and wrote the manuscript. CH and FR contributed to the clinical study, patients’ inclusion and analysis of the results. All the authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: DH benefitted from a ‘Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale’ (FDM20140630453) grant to conduct this study. This study was supported by a grant from the French National Cancer Institute (Institut National du Cancer, PRME-K2013), dedicated to economic studies of innovative techniques.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02813317) and was approved by the French National ethics committee (CCTIRS Authorization No. 14.602 and CNIL DR-2014-167) covering research at all participating hospitals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available

References

- 1. American Cancer Society, Inc. Breast Cancer Facts & figures 2013-2014 (2013) Atlanta. http://cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042725.pdf (accessed 20 Sep 2014).

- 2. Verdecchia A, Francisci S, Brenner H, et al. Recent cancer survival in Europe: a 2000-02 period analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:784–96. 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70246-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mehnert A, de Boer A, Feuerstein M. Employment challenges for cancer survivors. Cancer 2013;119(Suppl 11):2151–9. 10.1002/cncr.28067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balak F, Roelen CA, Koopmans PC, et al. Return to work after early-stage breast cancer: a cohort study into the effects of treatment and cancer-related symptoms. J Occup Rehabil 2008;18:267–72. 10.1007/s10926-008-9146-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. de Boer AG, Taskila TK, Tamminga SJ, et al. Interventions to enhance return-to-work for cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD007569 10.1002/14651858.CD007569.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fantoni SQ, Peugniez C, Duhamel A, et al. Factors related to return to work by women with breast cancer in northern France. J Occup Rehabil 2010;20:49–58. 10.1007/s10926-009-9215-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hedayati E, Johnsson A, Alinaghizadeh H, et al. Cognitive, psychosocial, somatic and treatment factors predicting return to work after breast cancer treatment. Scand J Caring Sci 2013;27:380–7. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lavigne JE, Griggs JJ, Tu XM, et al. Hot flashes, fatigue, treatment exposures and work productivity in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2008;2:296–302. 10.1007/s11764-008-0072-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baffert S, Hoang HL, Brédart A, et al. The patient-breast cancer care pathway: how could it be optimized? BMC Cancer 2015;15:394 10.1186/s12885-015-1417-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. ARC Foundation. Le retour au travail après un cancer: Brochure: Le retour au travail après un cancer; https://www.fondation-arc.org/support-information/brochure-retour-au-travail-apres-cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 11. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. R Core Team (2012) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. ISBN 3-900051-07-0 http://www.R-project.org/ [http://lib.stat.cmu.edu/r/CRAN (last accessed 20 Nov 2016).

- 12. Jagsi R, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term employment of survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Cancer 2014;120:1854–62. 10.1002/cncr.28607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnsson A, Fornander T, Rutqvist LE, et al. Predictors of return to work ten months after primary breast cancer surgery. Acta Oncol 2009;48:93–8. 10.1080/02841860802477899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eaker S, Wigertz A, Lambert PC, et al. Breast cancer, sickness absence, income and marital status. A study on life situation 1 year prior diagnosis compared to 3 and 5 years after diagnosis. PLoS One 2011;6:e18040 10.1371/journal.pone.0018040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Ruiter MB, Reneman L, Boogerd W, et al. Cerebral hyporesponsiveness and cognitive impairment 10 years after chemotherapy for breast cancer. Hum Brain Mapp 2011;32:1206–19. 10.1002/hbm.21102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reinertsen KV, Cvancarova M, Loge JH, et al. Predictors and course of chronic fatigue in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 2010;4:405–14. 10.1007/s11764-010-0145-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Islam T, Dahlui M, Majid HA, et al. Factors associated with return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2014;14(Suppl 3):S8 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S3-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Munir F, Burrows J, Yarker J, et al. Women’s perceptions of chemotherapy-induced cognitive side affects on work ability: a focus group study. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:1362–70. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoving JL, Broekhuizen ML, Frings-Dresen MH. Return to work of breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Cancer 2009;9:117 10.1186/1471-2407-9-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nesvold IL, Fosså SD, Holm I, et al. Arm/shoulder problems in breast cancer survivors are associated with reduced health and poorer physical quality of life. Acta Oncol 2010;49:347–53. 10.3109/02841860903302905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Assis MR, Marx AG, Magna LA, et al. Late morbidity in upper limb function and quality of life in women after breast cancer surgery. Braz J Phys Ther 2013;17:236–43. 10.1590/S1413-35552012005000088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Devoogdt N, Van Kampen M, Christiaens MR, et al. Short- and long-term recovery of upper limb function after axillary lymph node dissection. Eur J Cancer Care 2011;20:77–86. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hayes SC, Rye S, Battistutta D, et al. Upper-body morbidity following breast cancer treatment is common, may persist longer-term and adversely influences quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:92 10.1186/1477-7525-8-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stubblefield MD, Keole N. Upper body pain and functional disorders in patients with breast cancer. Pm R 2014;6:170–83. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.08.605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boyages J, Kalfa S, Xu Y, et al. Worse and worse off: the impact of lymphedema on work and career after breast cancer. Springerplus 2016;5:657 10.1186/s40064-016-2300-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peugniez C, Fantoni S, Leroyer A, et al. Return to work after treatment for breast cancer: single-center experience in a cohort of 273 patients. Ann Oncol 2010;21:2124–5. 10.1093/annonc/mdq556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hawkes AL, Gollschewski S, Lynch BM, et al. A telephone-delivered lifestyle intervention for colorectal cancer survivors ’CanChange': a pilot study. Psychooncology 2009;18:449–55. 10.1002/pon.1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sevellec M, Belin L, Bourrillon MF, et al. [Work ability in cancer patients: Six years assessment after diagnosis in a cohort of 153 workers]. Bull Cancer 2015;102(6 Suppl 1):S5–13. 10.1016/S0007-4551(15)31212-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inserm. VICAN2. https://www.inserm.fr/./rapport_complet_la-vie-2-ans-apres-un-diagnostic-de-cancer-2014

- 30. Drolet M, Maunsell E, Brisson J, et al. Not working 3 years after breast cancer: predictors in a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8305–12. 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020276supp001.jpg (214.9KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2017-020276supp002.pdf (36.5KB, pdf)