Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether balance and mobility training at home using Wii Fit is feasible and can provide clinical benefits.

Design

Single-group, pre–post intervention study.

Setting

Participants’ home.

Participants

20 children with cerebral palsy (6–12 years).

Intervention

Participants undertook 8 weeks of home-based Wii Fit training in addition to usual care.

Main measures

Feasibility was determined by adherence, performance, acceptability and safety. Clinical outcomes were strength, balance, mobility and participation measured at baseline (preintervention) and 8 weeks (postintervention).

Results

The training was feasible with 99% of training completed; performance on all games improved; parents understood the training (4/5), it did not interfere in life (3.8/5), was challenging (3.9/5) and would recommend it (3.9/5); and there were no injurious falls. Strength increased in dorsiflexors (Mean Difference (MD) 2.2 N m, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.2, p<0.001), plantarflexors (MD 2.2 N m, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.1, p<0.001) and quadriceps (MD 7.8 N m, 95% CI 5.2 to 10.5, p<0.001). Preferred walking speed increased (MD 0.25 m/s, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.41, p<0.01), fast speed increased (MD 0.24 m/s, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.35, p<0.001) and distance over 6 min increased (MD 28 m, 95% CI 10 to 45, p<0.01). Independence in participation increased (MD 1.4 out of 40, 95% CI 0.0 to 2.8, p=0.04).

Conclusions

Balance and mobility training at home using Wii Fit was feasible and safe and has the potential to improve strength and mobility, suggesting that a randomised trial is warranted.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12616001362482.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, balance, walking, physical therapy, Wii

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to test the feasibility of using a commercially available system to train balance and mobility in a resource-efficient way, that is, using Wii Fit games that required moving the base of support at home with minimal supervision.

Wii Fit games were employed to provide motivation and fun, in order to achieve high adherence.

The researchers that provided supervision and collected data were trained.

However, measurers were not blinded to the aims of the study and this could have influenced outcomes.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy is a non-progressive neurological condition resulting in permanent motor impairments which can originate from damage to an immature brain or indirectly from compensatory movements learnt during development.1 Current intervention in cerebral palsy has generally been aimed at the achievement of independent walking in infants and young children. Various interventions involved in assessing, treating and caring for children with cerebral palsy tend to focus on the achievement of walking. Even though children may undergo sessions of therapy throughout their childhood in order to achieve independent walking or at least walking with assistive device, their motor development appears to reach a plateau by 6–7 years of age.2 Furthermore, their ability to ambulate may gradually decline as they grow up3 or even be lost during adolescence or young adulthood.4 5 This indicates that current intervention for children over 7 years of age who have already achieved independent walking is of little value on the improvement of mobility. This may be because the content and environment of the intervention delivered in this child-oriented (or infant-oriented) approach are not suitable for older children or adolescents with cerebral palsy6 or children have little or no interest in conventional therapy by late childhood. Therefore, it is important to try and find an intervention that is effective and appeal to children of elementary school age.

Recently, virtual reality in the form of interactive computer games has been proposed as a potentially promising method of paediatric rehabilitation that meets the requirements of being motivating and engaging, while providing an opportunity for practice and repetition of real life skills.7 For example, Wii Fit is a commercially available interactive computer game consisting of fun activities that provide immediate feedback, are easy to pick up and come with progression built in so that the more difficult levels are able to challenge even the most experienced gamers. If children can be motivated to engage in therapy, they are more likely to practice, which in turn leads to the potential for improvement in mobility.8 9 Furthermore, this kind of interactive computer game can be used in the home in order to provide resource-efficient intervention.

Two previous studies of interactive computer games in children with cerebral palsy10 11 investigated using Wii Fit to train postural control and therefore used games that required the child to stand on the balance board and shift weight forwards, backwards or sideways. Both studies reported little or no effect on static postural sway, measured as centre of pressure. In another study using Wii Fit to train postural control,12 everyday mobility such as standing up from a chair, walking and stair climbing all improved. However, Wii Fit games that require moving the base of support such as marching on the spot or stepping up and down off the balance board may be more reflective of everyday mobility. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the feasibility of using a commercially available system to train balance and mobility in a resource-efficient way. The specific research questions were:

Is it feasible for elementary school children with cerebral palsy to train balance and mobility at home using Wii Fit?

Can 8 weeks of Wii Fit training improve strength, balance, walking and participation?

Method

Design

A single-group, pre–post intervention study was carried out. Children with cerebral palsy were recruited from elementary schools via advertisement or referral (from school therapists, cerebral palsy liaison officer and word of mouth) and screened by an independent recruiter. Participants undertook 8 weeks of Wii Fit training in their home, three times a week. Clinical measures were collected at baseline (before intervention) and at 8 weeks (after intervention). All measures were completed by a therapist trained in the measurement procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and parents/guardian of participants. This study was registered on the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12616001362482).

Participants

Children with cerebral palsy were included if they had been diagnosed with cerebral palsy before 5 years of age, were aged between 5 and 13 years, were classified level I, II or III at Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS).13 They were excluded (1) if they had severe cognitive and/or language deficits which precluded them from participation in the training sessions (as judged by researchers at screening or relatives); (2) if they had received botulinum toxin or surgery in the lower limb(s) during the previous 6 months.

Intervention

Participants undertook Wii Fit training at home for 20 min a session, three times a week over 8 weeks, that is, 24 sessions. Eight Wii Fit U games were chosen that targeted balance and/or mobility. Each session consisted of playing four of the eight games for 5 min each. The order of the games was counterbalanced so that each game was played 12 times over the 24 sessions. Participants were required to stand on the wireless Wii balance board which senses weight shift in any direction thereby allowing participants to use movement to drive an avatar onscreen. Children stood without or with hand support on the back of a chair, depending on their ability. Four of the games (Balance Bubble, Table Tilt, Perfect 10 and Super Hula Hoop) required the child to stand on the balance board and shift weight forwards/backwards or sideways in order to play the game. The other four games (Obstacle Course, Ultimate Obstacle Course, Ski Jump and Basic Step) required the child to march on the spot, squat and extend the legs, or step up and down off the balance board forwards/backwards or sideways in order to play the game. Videotaped examples of the individual games can be found on the official Nintendo website.14

Each participant was assigned one of eight therapists trained in the eight games who supervised one session a week and parents supervised the other two sessions. At the beginning of the 8 weeks, the therapist made sure that the children and their parents understood the eight games, and that they were available for follow-up telephone calls if necessary. The scores of each game played were recorded to estimate compliance and performance. Participants continued usual care which may have involved physiotherapy for up to 2 hours per week.

Outcome measures

Feasibility

Feasibility of using Wii Fit at home involved examining recruitment, intervention (adherence, performance, acceptability and safety) and measurement. Feasibility of recruitment was determined by calculating the number of eligible and enrolled participants as a proportion of the screened population of children between 5 and 13 years of age having had cerebral palsy. Feasibility of the intervention was determining adherence of the participant to the intervention and performance over time. Acceptability of the intervention was determined from a survey in which four statements about the training were rated on a five-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4). The four statements for parents were: ‘I clearly understood the purpose of using Wii Fit’, ‘Using Wii Fit did not interfere with our daily life’, ‘Using Wii Fit is challenging for my child’ and ‘I would recommend using the Wii Fit to others having children with cerebral palsy’. The four statements for participants were: ‘I think walking becomes easier after using the Wii Fit’, ‘I enjoyed using the Wii Fit’, ‘Using the Wii Fit was challenging’ and ‘If you left Wii Fit with me, I would keep using it’. Safety was measured by recording events such as muscle soreness, fatigue, non-injurious falls and injurious falls. Feasibility of measurement was determined by being able to measure the clinical outcomes in all participants.

Clinical outcomes

Strength was measured as maximum voluntary isometric contraction of knee extensors, ankle dorsiflexors and plantarflexors in the most-affected limb using the PowerTrack II commander (Australasian Medical & Therapeutic Instruments, Australia, 125 pounds rated capacity, linearity 1%). Newtons were multiplied by length of the part of body in order to report torque (N m).

Balance was measured using the One-Legged Stance Test and reported in seconds.15 16 This test requires the participant to stand on one leg and to maintain this for as long as possible. Participants stood unassisted on the most affected leg with eyes open and timing began once one foot was lifted off the floor and stopped when the foot touched the ground or the weight bearing leg moved.

Walking was measured using 10 m Walk Test and the 6 min Walk Test. The 10 m Walk Test was performed at preferred and fast speed and speed was reported in metres per second. This test is a simple, submaximal, clinical exercise test, in which speed walked barefoot over 10 m reflects quality of walking17 and is valid for children with cerebral palsy.18 The 6 min Walk Test was performed with shoes and usual aids and distance covered reported in metres. This test is a simple, submaximal, clinical exercise test, in which distance walked in 6 min with shoes and aids reflects community ambulation19 20 and is valid for children with cerebral palsy.21

Participation was measured using the Assistance to Participation Scale, an eight-item questionnaire which has been previously used to study participation in children with cerebral palsy.22 The eight questions capture levels of assistance with life within eight different domains (watching television, listening to music, playing with a toy/activity alone inside the house, playing with a toy/activity alone outside the house, sharing time with a friend within the house, sharing time with a friend at the friend’s house, spending time at a playground or outdoor recreation area, attending an organised recreational club). Caregivers indicate the number from 1 (unable to participate) to 5 (participates independently). The score was calculated as a sum (8–40) to gauge independence of participation in play and leisure.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables at both times (weeks 0 and 8). The between-time differences in strength, balance, walking and participation from baseline to 8 weeks were analysed using paired t-tests23 if normally distributed to ascertain statistical significance, which was set at 0.05. The mean between-time differences (95% CI) were calculated to ascertain the clinical significance. Analyses were performed using Statistica, v.10.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Twenty children with cerebral palsy aged 8 years 9 months (SD 2 years 5 months), of which 11 (55%) were male, participated in the study (table 1). Eighteen (90%) participants were born prematurely. Eight participants were hemiplegic (40%), 10 were diplegic (50%) and 2 were quadriplegic (10%). Seventeen (85%) participants were levels I and II of GMFCS and Manual Ability Classification System.24 Usual care incorporated an average of 1 hour per week (SD 0.7) of physiotherapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Characteristic of participants | n=20 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 8.7 (2.4) |

| Gender (males), n (%) | 11 (55) |

| Gestation (premature), n (%) | 18 (90) |

| Type of cerebral palsy, n (%) | |

| Hemiplegia | 8 (40) |

| Diplegia | 10 (50) |

| Quadriplegia | 2 (10) |

| Education class, n (%) | |

| Regular | 11 (55) |

| Resource | 6 (30) |

| Special | 3 (15) |

| GMFCS, n (%) | |

| Levels I and II | 17 (85) |

| Level III | 3 (15) |

| MACS, n (%) | |

| Levels I and II | 17 (85) |

| Level III | 3 (15) |

| Physiotherapy service (hours per week), mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.7) |

GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; MACS, Manual Ability Classification System.

Feasibility

Recruitment

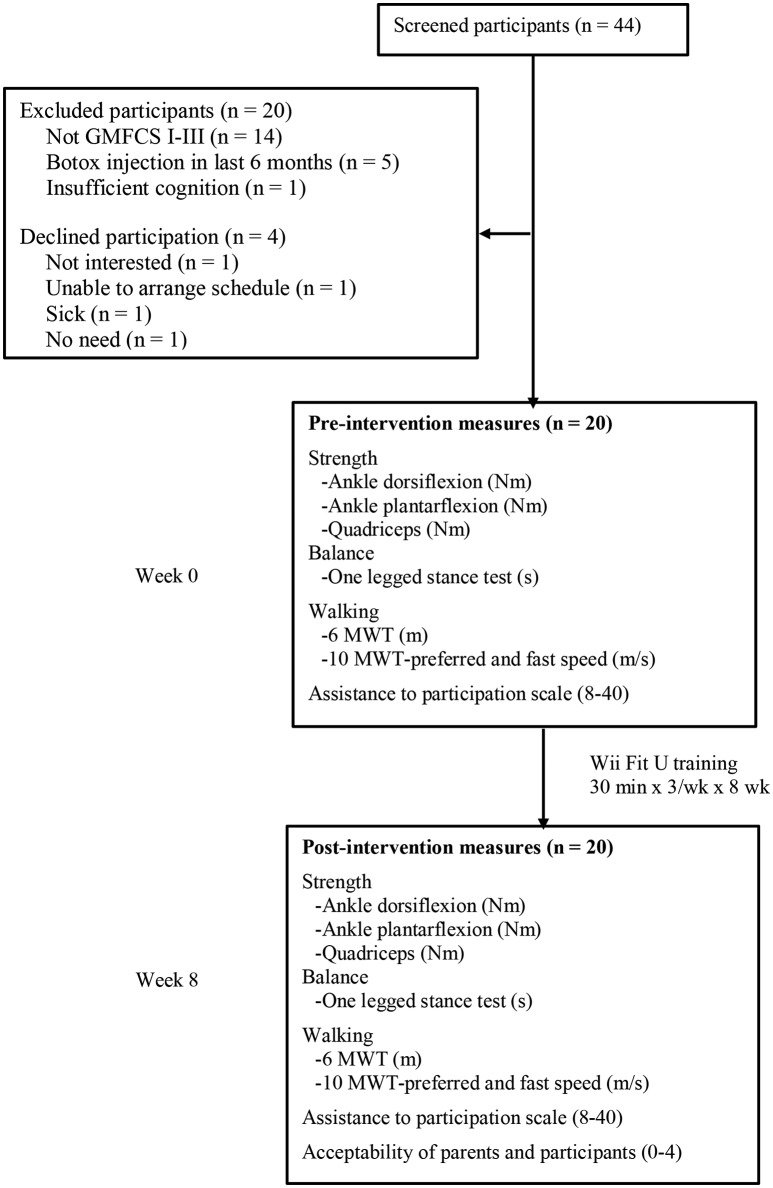

Forty-four children with cerebral palsy were screened over 1 year (figure 1). Twenty-four were eligible giving an eligibility fraction of 55%. Twenty were enrolled giving a recruitment fraction of 45%. There were no dropouts and flow of participants through the trial is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Design and flow of participants through the trial. GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; 6 MWT, 6 min Walk Test; 10 MWT, 10 m Walk Test; wk, week.

Intervention

In terms of adherence, each participant should have completed 24 sessions of training so the 20 participants should have completed 480 sessions. Since 477 sessions were completed, the overall adherence was 99%. In terms of performance over time, the scores improved by 18%–179% (table 2). However, the improvement in one game (Super hula hoop) had wide CIs, suggesting a large variability in improvement. In terms of acceptability, 20 (100%) parents rated:

Table 2.

Mean (SD) of performance of intervention at each time, mean difference between times (week 8 minus week 0) (95% CI) and percentage improvement between times (n=20)

| Outcome | Times | Difference between times | |

| Week 0 | Week 8 | Week 8 minus week 0 | |

| Perfect 10 (0–20) | 11 (3) | 14 (4) | 2 (1 to 3) ↑ 18% |

| Balance Bubble (0–1200) | 673 (242) | 900 (286) | 227 (134 to 321) ↑ 34% |

| Table Tilt (higher score) | 32 (10) | 48 (18) | 16 (8 to 25) ↑ 50% |

| Ski jump (m) | 109 (59) | 166 (100) | 57 (16 to 98) ↑ 52% |

| Basic Step (higher score) | 98 (40) | 149 (62) | 51 (34 to 67) ↑ 52% |

| Ultimate Obstacle Course (m) | 132 (78) | 240 (162) | 108 (53 to 163) ↑ 82% |

| Obstacle Course (m) | 73 (76) | 204 (153) | 131 (80 to 182) ↑ 179% |

| Super Hula Hoop (higher score) | 35 (53) | 160 (345) | 126 (−29 to 280) |

Percentage (%) improvement was calculated by mean difference between times/baseline.

understanding the purpose of using the Wii Fit as 4.0 out of 5.0 (SD 0);

using the Wii Fit did not interfere with daily life as 3.8 (SD 0.5);

the challenge of the training as 3.9 (SD 0.3);

whether they would recommend the training to others having children with cerebral palsy as 3.9 (SD 0.3).

Twenty (100%) participants rated:

walking becomes easier after using the Wii Fit as 2.8 out of 5.0 (SD 1.0);

enjoying using the Wii Fit as 3.6 (SD 0.8);

the challenge of the training as 3.6 (SD 0.7);

whether they would like to keep using the Wii Fit after the completion of training as 3.4 (SD 0.8).

In terms of safety, two (10%) participants reported muscle soreness most sessions and nine (45%) reported it occasionally. Three (15%) participants reported fatigue most sessions and seven (35%) reported it occasionally. Three (15%) participants reported non-injurious falls most sessions and five (25%) reported falling occasionally. However, none of these events were serious enough to stop participants from training. Five (25%) participants needed to use hand support on the back of a chair for some games.

Measurement

Measurement of the clinical outcomes was completed for all participants. However, the One-Legged Stance Test yielded highly skewed results. Most participants (75%) scored <2 s at both preintervention and postintervention measures, indicating a floor effect in the measure. Therefore, the scores from this measure were not included in the analysis.

Clinical outcomes

Group data for the two measurement occasions and between-time differences are presented in table 3 for all clinical outcomes. Compared with baseline, strength increased in dorsiflexors (Mean Difference (MD) 2.2 N m, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.2, p<0.001), plantarflexors (MD 2.2 N m, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.1, p<0.001) and quadriceps (MD 7.8 N m, 95% CI 5.2 to 10.5, p<0.001). Walking increased at preferred speed (MD 0.25 m/s, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.41, p=0.004), at fast speed (MD 0.24 m/s, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.35, p=0.0001), and distance over 6 min also increased (MD 28 m, 95% CI 10 to 45, p=0.004). Independence in participation increased (MD 1.4 out of 40, 95% CI 0.0 to 2.8, p=0.04).

Table 3.

Mean (SD) of clinical outcomes at each time and mean difference between times (week 8 minus week 0) (95% CI) (n=20)

| Outcome | Times | Difference between times | |

| Week 0 | Week 8 | Week 8 minus week 0 | |

| Strength | |||

| Ankle dorsiflexion (N m) | 4.2 (2.8) | 6.4 (3.1) | 2.2 (1.1 to 3.2) |

| Ankle plantarflexion (N m) | 3.7 (2.8) | 6.0 (3.4) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.1) |

| Quadriceps (N m) | 14.0 (8. 3) | 21.8 (10.9) | 7.8 (5.2 to 10.5) |

| Walking activities | |||

| 6 min Walk Test (m/s) | 319 (131) | 346 (141) | 28 (10 to 45) |

| 10 m Walk Test—preferred speed (m/s) | 1.04 (0.51) | 1.29 (0.69) | 0.25 (0.09 to 0.41) |

| 10 m Walk Test—fast speed (m/s) | 1.42 (0.66) | 1.66 (0.77) | 0.24 (0.13 to 0.35) |

| Assistance to Participation Scale | |||

| Score (8–40) | 32.3 (7.2) | 33.7 (6.6) | 1.4 (0.0 to 2.8) |

Discussion

This study demonstrates that balance and mobility training at home using the Wii Fit in children with cerebral palsy is feasible and safe, and that parent’s and children’s rating of satisfaction was high. The Wii Fit games required the children to stand on a balance board and to shift weight, march on the spot, squat or step up and down off the balance board forward, backwards or sideways. The clinical outcomes demonstrate that Wii Fit training has the potential to improve lower limb strength and walking.

The recruitment rate (45%) was usual. The most common reason for exclusion was because children were GMFCS IV or V. Although we included some children with cerebral palsy who were GMFCS III, they were not able to perform all the games without hand support. Other studies investigating Wii Fit training only included children with cerebral palsy at GMFCS I and II.10 11 Perhaps children who are GMFCS III require less challenging games and different measures to investigate their response to Wii Fit training.

Adherence to the Wii Fit training was extremely high and both parents and children rated satisfaction as high. The finding that Wii Fit training was appealing is consistent with previous findings that children with cerebral palsy enjoy playing interactive computer games.12 25–28 Interactive computer games are engaging and appear to motivate children to participate even when a therapist is not present. Only one child reported becoming bored, stating that he ‘would rather play with X-box’. In another study investigating Wii Fit training,11 22% participants dropped out or lost interest and stopped practising. The children in this study were older than in the present study, which may explain why Wii Fit training was less appealing.

Performance in the Wii Fit games improved over time. However, in two games, the CIs around the mean improvement were high, because only five participants (25%) improved. These two games (Obstacle course and Super hula hoop) are too difficult for most children with cerebral palsy, and may be better reserved to act as a challenge for mildly disabled children.

Safety of training at home using Wii Fit was acceptable. Fifty per cent of children reported some muscle soreness and 50% reported some fatigue, suggesting that the training provided a strenuous workout. Forty per cent had non-injurious falls during training, five fell one to two times and three fell more than three times. Two of the children who fell more than three times were less than 7 years old, and this may account for their inability to keep their balance while on the balance board. Although other researchers consider that more severely disabled (ie, GMFCS III) may be at a higher risk of falls,28 we did not find this since these children tended to be cautious during training. Neither non-injurious falls, fatigue nor general muscle soreness impacted on willingness or ability to complete the training.

Two of the measures used to reflect clinical benefit were problematic. In the One-Legged Stance Test, only 5 of 20 participants (25%) could perform the test adequately and they were above normal level, implying that measure of balance was unable to distinguish the severity. In two previous studies of Wii Fit training,10 11 balance measured as postural sway did not show improvements. Perhaps balance can best be examined when embedded in everyday activities, such as walking. There was little change found in the Assistance to Participation Scale. This was despite the fact that parents and children perceived an increase in participation such as ‘my children can walk faster and longer distance when we went out after the intervention’, ‘I have done something that I was unable to do before’, ‘It was fun because I would not have usually had the opportunity to learn these games’, ‘I have felt more confident to achieve things’. A measure of participation that better reflects mobility such as Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment and the Preferences for Activities of Children which include diversity, intensity and enjoyment of children’s participation could be used in future.

There were significant improvements in all measures of lower limb strength and in all three measures of walking, suggesting that Wii Fit training in the home has the potential to be beneficial in children with cerebral palsy. The time to walk 10 m decreased by 17% which is consistent with a recent study investigating a similar amount of Wii Fit training in slightly older children with cerebral palsy.12 The amount of improvement in the strength and walking suggests that further investigation is warranted, and this study provides useful information for the design of a randomised controlled trial.

This feasibility study has both strengths and limitations. The main strength of the study is that the children were engaged in training, implying that Wii Fit games provided motivation and fun, so that adherence was almost maximum. This is despite the fact that only 33% of the sessions were supervised. On the other hand, we cannot be sure of the potential effect of the Wii Fit training on balance because the measure we used demonstrated a floor effect. In addition, the measure of participation demonstrated a ceiling effect.

In conclusion, this study suggests that balance and mobility training at home using a commercially available interactive computer game—Wii Fit—is feasible and safe and may confer clinical benefits on children with cerebral palsy. It appears to be a promising way of improving walking in children with cerebral palsy and warrants further study in a randomised controlled trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the participation of the children and their parents to make this study possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: HCC, chief investigator for study and lead author, obtained ethics approval, assembled team, recruited participants, collected and analysed data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LA advised on study design, was involved in data processing, data analysis and interpretation of findings, and contributed to revision of the manuscript. S-DL advised on study design, was involved in data collection, and interpretation of findings and contributed to revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was, in part, supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, under grant number MOST 104-2314-B-214-006 and by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center, under grant number MOHW106-TDU-B-212-113004.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Parental/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: National Cheng Kung University Governance Framework for Human Research Ethics.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is unpublished data in relation to the progression of all games for all participants, which can be obtained by contacting the chief investigator.

References

- 1. Wright M, Wallman L. Cerebral Palsy : Campbell SK, Palisano RJ, Orlin MN, Physical therapy for children. 4 ed St. Louis: Elsvier Saunders, 2012:577–627. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koop SE. The Natural History of Ambulation in Cerebral Palsy : Gage JR, Schwartz MH, Koop SE, Novacheck TF, The Indentification and Treatment of Gait Problems in Cerebral Palsy. 2 ed London: Mac Keith Press, 2009:167–78. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gannotti M, Gorton GE, Nahorniak MT, et al. Changes in gait velocity, mean knee flexion in stance, body mass index, and popliteal angle with age in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop 2008;28:103–11. 10.1097/bpo.0b013e31815b12b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Day SM, Wu YW, Strauss DJ, et al. Change in ambulatory ability of adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;49:647–53. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00647.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bottos M, Feliciangeli A, Sciuto L, et al. Functional status of adults with cerebral palsy and implications for treatment of children. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001;43:516–28. 10.1017/S0012162201000950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams J. Children with disability grow into adults with a disability. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50:163 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.00163.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Galvin J, Levac D. Facilitating clinical decision-making about the use of virtual reality within paediatric motor rehabilitation: describing and classifying virtual reality systems. Dev Neurorehabil 2011;14:112–22. 10.3109/17518423.2010.535805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sandlund M, McDonough S, Häger-Ross C. Interactive computer play in rehabilitation of children with sensorimotor disorders: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2009;51:173–9. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03184.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Snider L, Majnemer A, Darsaklis V. Virtual reality as a therapeutic modality for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Neurorehabil 2010;13:120–8. 10.3109/17518420903357753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gatica-Rojas V, Méndez-Rebolledo G, Guzman-Muñoz E, et al. Does Nintendo Wii Balance Board improve standing balance? A randomized controlled trial in children with cerebral palsy. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2017;53 Epub ahead of print 10.23736/S1973-9087.16.04447-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramstrand N, Lygnegård F. Can balance in children with cerebral palsy improve through use of an activity promoting computer game? Technol Health Care 2012;20:501–10. 10.3233/THC-2012-0696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tarakci D, Ersoz Huseyinsinoglu B, Tarakci E, et al. Effects of Nintendo Wii-Fit video games on balance in children with mild cerebral palsy. Pediatr Int 2016;58:1042–50. 10.1111/ped.12942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, et al. Gross motor function classification system for cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997;39:214–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nintendo. Wii Fit U. 2013. http://wiifitu.nintendo.com/ (accessed 25 Aug 2017).

- 15. Blythe SD. Neuromotor immaturity in children and adults: The INPP screening test for health clinicians and practitioners. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liao HF, Mao PJ, Hwang AW. Test-retest reliability of balance tests in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001;43:180–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watson MJ. Refining the Ten-metre Walking Test for Use with Neurologically Impaired People. Physiotherapy 2002;88:386–97. 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)61264-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chrysagis N, Skordilis EK, Koutsouki D. Validity and clinical utility of functional assessments in children with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:369–74. 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Geiger R, Strasak A, Treml B, et al. Six-minute walk test in children and adolescents. J Pediatr 2007;150:395–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.12.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maher CA, Williams MT, Olds TS. The six-minute walk test for children with cerebral palsy. Int J Rehabil Res 2008;31:185–8. 10.1097/MRR.0b013e32830150f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nsenga Leunkeu A, Shephard RJ, Ahmaidi S. Six-minute walk test in children with cerebral palsy gross motor function classification system levels I and II: reproducibility, validity, and training effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:2333–9. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bourke THM, Law M, Howie L. Assistance to Participate Scale (APS) for children with disabilities participation in play and leisure information booklet Hamilton Available. 2010. www.canchild.ca (accessed 25 Aug 2017).

- 23. Portney LG, Watkins MP. The t-Test : Portney LG, Watkins MP, Foundations of clinical research: Applications to practice. 3 ed New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2009:443–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eliasson AC, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Rösblad B, et al. The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev Med Child Neurol 2006;48:549–54. 10.1017/S0012162206001162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chiu HC, Ada L, Lee HM. Upper limb training using Wii Sports Resort for children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: a randomized, single-blind trial. Clin Rehabil 2014;28:1015–24. 10.1177/0269215514533709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Deutsch JE, Borbely M, Filler J, et al. Use of a low-cost, commercially available gaming console (Wii) for rehabilitation of an adolescent with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther 2008;88:1196–207. 10.2522/ptj.20080062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gordon C, Roopchand-Martin S, Gregg A. Potential of the Nintendo Wii™ as a rehabilitation tool for children with cerebral palsy in a developing country: a pilot study. Physiotherapy 2012;98:238–42. 10.1016/j.physio.2012.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Radtka S, Hone R, Brown C, et al. Feasibility of Computer-Based Videogame Therapy for Children with Cerebral Palsy. Games Health J 2013;2:222–8. 10.1089/g4h.2012.0071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.