Abstract

Adaptive immune responses are initiated by triggering of the T cell receptor. Single-molecule imaging based on total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy at coverslip/basal cell interfaces is commonly used to study this process. These experiments have suggested, unexpectedly, that the diffusional behavior and organization of signaling proteins and receptors may be constrained before activation. However, it is unclear to what extent the molecular behavior and cell state is affected by the imaging conditions, i.e., by the presence of a supporting surface. In this study, we implemented single-molecule light-sheet microscopy, which enables single receptors to be directly visualized at any plane in a cell to study protein dynamics and organization in live, resting T cells. The light sheet enabled the acquisition of high-quality single-molecule fluorescence images that were comparable to those of total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. By comparing the apical and basal surfaces of surface-contacting T cells using single-molecule light-sheet microscopy, we found that most coated-glass surfaces and supported lipid bilayers profoundly affected the diffusion of membrane proteins (T cell receptor and CD45) and that all the surfaces induced calcium influx to various degrees. Our results suggest that, when studying resting T cells, surfaces are best avoided, which we achieve here by suspending cells in agarose.

Introduction

T cell activation requires the engagement of membrane receptors by their ligands, which leads to downstream signaling (1) and activation of an adaptive immune response. This process is believed to depend especially on the dynamics (2) and spatial organization (3) of a few key membrane proteins, including the T cell receptor (TCR), which recognizes antigens leading to the signaling cascade that drives the immune response (2), and CD45, a protein tyrosine phosphatase that controls activation via dephosphorylation of the TCR and the Src kinases that phosphorylate the receptor, including Lck (4). Although important aspects of the activation mechanism have been investigated using single-molecule fluorescence imaging (1, 5, 6, 7), revealing unexpected phenomena such as the formation of protein nanoclusters (8, 9) and TCR triggering elicited by the passive reorganization of proteins at “close contacts” (10), the organization and dynamics of proteins in nonactivated or “resting” T cells are less well described. Their elucidation is vital to determine the initial state from which receptor triggering is initiated and hence to completely understand the mechanisms responsible for T cell activation. It is therefore important to develop new biophysical methods for imaging T cells as closely to their resting state as possible.

The homopolymer poly-L-lysine (PLL) has been widely used as a surface coating to facilitate the imaging of T cells that were presumed to be resting using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM) (9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20). However, given that the contact of T cells with a PLL-coated surface is known to induce partial immobilization of the TCR (21), the possibility arises that the resting state of a T cell is perturbed under these conditions. We recently showed that bona fide TCR triggering is induced by the spatial reorganization of surface receptors on the plasma membrane when T cells contact protein-coated glass surfaces lacking TCR ligands by altering the phosphorylation state of the TCR at the single-receptor level (10, 22). In these experiments and others (23, 24), noninteracting proteins, such as nonspecific immunoglobulin G (IgG), were used in attempts to passivate the glass surface (10). Supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) have been used to create more physiological surfaces (22, 25), which typically require the use of adhesion molecules to anchor the cells to the surface for imaging. However, even the disruption of highly dynamic and “ruffled” surfaces of T cells (26) when they adhere to lipid bilayers represents a potentially significant perturbation of the cells’ physiology, which could be related to the integrin out-to-in signaling that is known to take place on SLBs (27). Furthermore, we have shown that ligand-independent triggering can occur on SLBs when contact is mediated with small, nonsignaling adhesion molecules only (10). Given these uncertainties, there is a need to understand the extent to which surface contact per se affects the dynamics and spatial organization of single receptors at cell-glass interfaces, i.e., at the basal plane characterized using TIRFM versus those less likely to be perturbed, e.g., receptors at the apical surface imaged using other approaches.

In recent years, new techniques have been developed that can image individual membrane proteins away from the coverslip interface (28). For example, single-molecule light-sheet microscopy (smLSM) has been used to monitor the reorganization of the TCR during T cell activation at subdiffraction resolution (29). Here, we apply smLSM to study the dynamics and organization of two well-characterized (30) and critically important (5) surface proteins known as TCR and CD45 in Jurkat T cells. We show that all commonly used strategies for representing resting T cells on surfaces, such as PLL, passivation, and SLBs, either fail to immobilize cells for imaging or perturb membrane protein dynamics, cause CD45 exclusion, and induce calcium signaling. Our results suggest that truly resting T cells may have to be imaged away from surfaces altogether. We achieve this by using smLSM to image cells suspended in a gel, establishing a platform for single-molecule imaging of live, resting T cells.

Materials and Methods

Full description of the methods can be found in Supporting Materials and Methods.

Cell culture and labeling

TCR and CD45 proteins in a Jurkat T cell line were labeled using antigen-binding fragments UCHT1 (TCR) and Gap8.3 (CD45), respectively, and labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Supporting Materials and Methods).

Single-molecule imaging

TIRFM

Through-objective TIRFM was performed at room temperature (20°C) using a 488-nm fiber-coupled diode laser and a 100× 1.49 NA objective lens, with images being captured on an electron-multiplying charge-coupled device camera at a frame rate of 20 Hz (Supporting Materials and Methods).

smLSM

A secondary perpendicular objective lens was used to introduce a light sheet created using cylindrical lenses. TIRFM and smLSM could be switched between using a reversible mirror for direct comparison. A custom-made sample chamber was constructed to allow the light sheet to enter the sample with minimal aberrations (Supporting Materials and Methods and Fig. S2). The thickness of the sheet was measured to be 1.3 μm by measuring the point-spread function of 100 nm beads (Supporting Materials and Methods and Fig. S3). Experiments were carried out at room temperature (20°C).

Single-molecule tracking

Spot detection

A custom-made MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) script (31) was used to detect localizations with a signal-to-noise ratio above 3 (Supporting Materials and Methods). Visualization in Fig. 3 was performed with the Trackmate plugin for ImageJ (32).

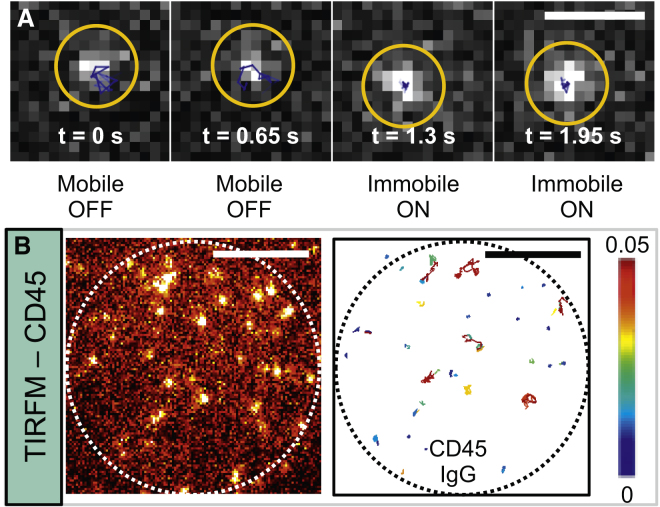

Figure 3.

T cell membrane proteins interact even with nonspecific IgG. (A) Sample TIRFM data show how initially mobile CD45 above the surface sits down on IgG, becoming immobile. The blue track corresponds to the local 11 tracks from −5 to 5 frames. The yellow circle indicates the molecule. The scale bar represents 1 μm. Visualization was performed with the Trackmate plugin for ImageJ. (B) A sample TIRFM frame (left) of CD45 on IgG is shown with corresponding analyzed tracks (right) colored by diffusion coefficient (see color bar). The scale bar represents 5 μm. The dotted circle represents the size of the cell-IgG interface. To see this figure in color, go online.

MSD analysis

The ensemble mean-square displacement (MSD) was constructed for each cell, and the first five points (250 ms) of the curve were fitted to determine the diffusion coefficient (Supporting Materials and Methods).

JD analysis

Jump distance (JD) analysis (31) was applied to investigate heterogeneities in the diffusion coefficient distribution. The probability distribution of the squared distance, , traveled in one time step, , was fitted using

where is the fraction corresponding to population , and is the number of populations. JD distributions can be fitted with more than one population, but this is not always appropriate. A two-component fit to a single diffusing population, D, would result in D1 < D < D2. In this work, the purpose of the JD analysis is to identify an immobile population. JD analysis of fixed cells indicates that an immobile population will have a diffusion coefficient of 0.012 μm2/s, whereas the two-component fit to this data incorrectly results in D1 = 0.005 and D2 = 0.025. We chose the following criteria for using two-component fits based on the fixed data: D1 < 0.03 and D2 > 0.03. This avoids fitting two components simply because of splitting a single population into two and instead necessitates both immobile and mobile populations.

Results

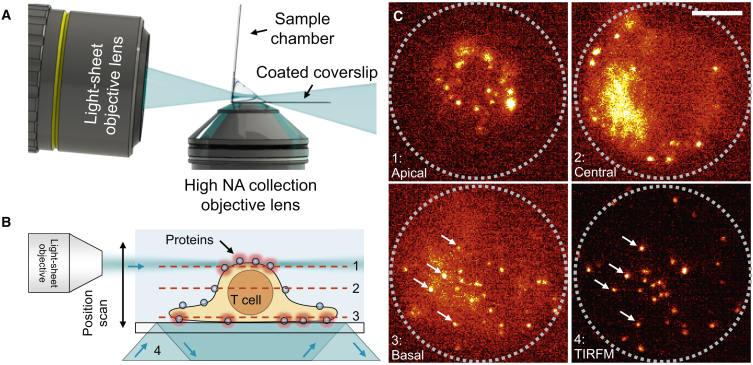

Off-surface single-molecule fluorescence imaging of T cell membrane proteins using smLSM

smLSM was implemented using a bespoke instrument (Figs. S1 and S2) described in the Materials and Methods and shown schematically in Fig. 1 A. The axially thin light sheet (1.3 μm fullwidth at half-maximum; see Supporting Materials and Methods and Fig. S3) enables single-molecule imaging by reducing unwanted background fluorescence due to only a single plane of the cell being illuminated. We used smLSM to perform single-molecule imaging of the fluorescently labeled membrane proteins TCR and CD45 in live Jurkat T cells. We imaged the TCR, labeled with Alexa-Fluor-488-tagged (degree of labeling ∼2) antigen-binding fragments (Fabs), on the apical surface of T cells resting on coated cover slips (Fig. 1 B). We first compared the performance of the light sheet to standard epifluorescence (EpiFL) illumination (Figs. S4 and S5) at similar laser power densities (0.1 kW/cm2) to those typically used in experiments (Video S1). smLSM provided improved contrast and facilitated accurate identification of single fluorescent molecules compared to EpiFL illumination. To quantify this difference, we imaged the same three cells using both techniques. Tracking of single molecules was done as described in Materials and Methods. As expected, the light sheet gives a substantial increase in contrast of tracked particles (median signal-to-noise ratio: EpiFL - 4.0 ± 1.6, smLSM - 5.9 ± 3.2, Figs. S4 and S5). This is a clear demonstration of a system wherein EpiFL illumination is prone to inaccurate tracking, as results are highly dependent on analysis parameters (see Supporting Materials and Methods for comparison) and smLSM is required to successfully identify most molecules. We therefore conclude that the instrument is a suitable platform for quantitative single-molecule diffusion studies.

Figure 1.

Single-molecule imaging of membrane proteins on the apical surface of living T cells. (A) A schematic depicts smLSM geometry. (B) A schematic of the experiment shows how scanning of the light sheet enables sectioning of the T cell. The numbers correspond to four distinct cases in (C). (C) The same T cell was imaged at the apical (1), central (2), and basal (3) planes using smLSM and at the basal plane using TIRFM (4). The gray dotted circle represents the size of the cell after spreading on a PLL-coated coverslip. The arrows in 3–4 highlight the same molecules imaged using smLSM (3) and TIRFM (4). The scale bar represents 5 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

We also compared smLSM performance to that of TIRFM. We could observe stepwise photobleaching (Video S3. Sample TIRFM Videos of TCR in Cells Resting on PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle, Compared with Imaging in Agarose, Right, Video S4. Sample smLSM Videos of TCR on the Apical Surface of Three Different T Cells Resting on Either PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle, and Suspended in Agarose, Right, Video S6. Sample TIRFM Videos of CD45 in Cells Resting on PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle Compared with Imaging in Agarose, Right, Video S7. Sample smLSM Videos of CD45 on the Apical Surface of Three Different T Cells Resting on Either PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle, and Suspended in Agarose, Right, Video S10. TIRFM Video of Membrane Stain CellMask Deep Red Showing How T Cell Microvilli Move around on ICAM-1 SLBs, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material) using both TIRFM and smLSM, indicating that we were tracking single Fabs. Fig. 1 B shows a schematic representation of a T cell attached to a PLL-coated coverslip, which pulls the cell membrane toward the coverslip. As shown, four excitation conditions (1–4) were explored. In the first three, the light sheet was used to image the top (1), middle (2), or bottom (3) of the same cell. In the final case, the bottom of the cell was imaged using “standard” TIRFM (4). Sample images acquired under these conditions, with TCRs labeled using Alexa Fluor 488-Fab, are shown in Fig. 1 C (also see Video S2). These images were all taken using the same cell within 1 min, and the excitation power density was kept low (0.01 kW/cm2) to minimize photobleaching. Because the PLL appeared to immobilize the TCR, the same proteins could be identified (white arrows in Fig. 1 C, conditions 3 and 4) using both techniques, albeit with a larger autofluorescence background in condition 3. The light sheet enables acquisition of high-quality single-molecule fluorescence images that are comparable to those of TIRFM.

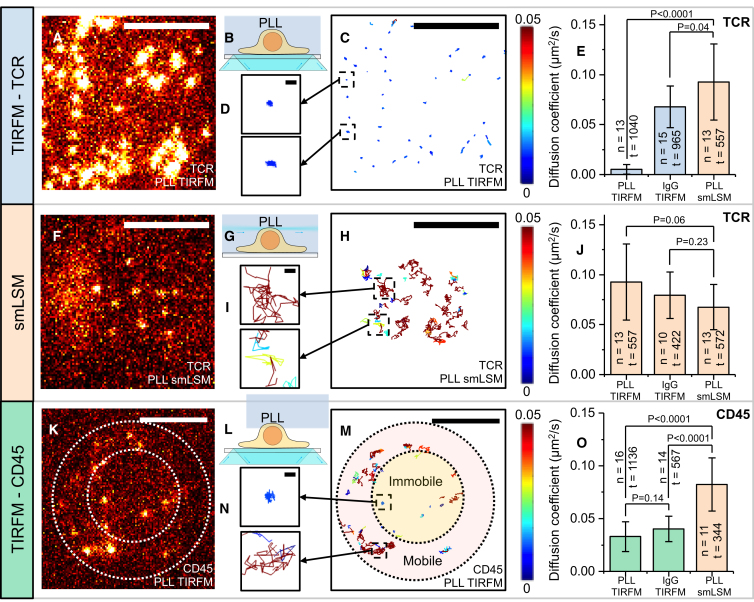

PLL completely immobilizes T cell membrane proteins on glass surfaces

The application of smLSM enables precise measurements of the mobility of membrane proteins far above the coverslip, where they are unlikely to be affected by interactions with surfaces. This can be compared with results obtained for the same cell probed at the cell/coverslip interface using TIRFM, allowing the influence of the surface on the mobility of proteins to be established. The diffusion coefficient of the TCR on PLL-coated coverslips was measured at room temperature using TIRFM (Fig. 2, A–D) at a power density of 0.1 kW/cm2. An example of ensemble MSD curves and diffusion coefficient histograms is shown in Fig. S7. Compared to an expected value between 0.06 μm2/s at 37°C (8), determined by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, and 0.12 μm2/s at room temperature (33), measured by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, the positively charged coating completely immobilized the TCR (D = 0.005 ± 0.005 μm2/s; Fig. 2 C; Video S3). Here, we define “immobile” as anything below 0.01 μm2/s, based on diffusion measurements of TCRs in fixed cells on PLL (D = 0.005 ± 0.004 μm2/s, 10 cells). Note the discrepancy in literature values for TCR diffusion, which is higher at lower temperatures. This highlights the variation in measurements based on techniques, suggesting that orthogonal measurements using novel techniques such as smLSM are needed. When measurements were taken on the apical surface of cells on PLL (corresponding to position 1 in Fig. 1, B and C) using smLSM (Fig. 2, F–H), the diffusion coefficient was significantly larger (D = 0.093 ± 0.038 μm2/s; Fig. 2, E and J; Video S4), which is within the range of literature values (8, 33), indicating that the observed immobilization was caused by surface interactions. The immobilization of TCR by PLL could also be observed when we imaged the TCR using a HaloTag fusion protein labeled with silicon rhodamine using TIRFM (Video S5), which means that the observed effect is not caused by the presence of the Fabs. However, we saw more TCRs using smLSM than TIRFM when imaging the same cell (Video S5), and some TCRs were now mobile, suggesting that the HaloTag labeling protocol resulted in intracellular staining. We therefore chose to label proteins using Fabs. We also measured the diffusion coefficient of CD45 (Fig. 2 O), which has a significantly larger extracellular domain than that of the TCR (∼21 nm vs. ∼8 nm) (10). It appeared initially as though CD45, unlike the TCR, retained some mobility on PLL. However, visual inspection of Fig. 2, K–M and Video S6 suggested that CD45 was mostly excluded from the glass-cell interface likely because of the large extracellular domain and that the CD45 located inside the interface remained immobile like the TCR.

Figure 2.

PLL immobilizes TCR and CD45. (A, F, and K) Sample single-molecule images of T cell proteins on the basal (A and K) and apical (F) surfaces are shown. The scale bar represents 5 μm. The TIRFM data appear to be saturated because they have been contrast-matched with the smLSM data. (B, G, and L) Schematics of the excitation schemes corresponding to (A), (F), and (K) are shown. (C, H, and M) Tracking results from (A), (F), and (K) are shown. The color of each track corresponds to the diffusion coefficient determined by MSD analysis. The scale bar represents 5 μm. (D, I, and N) A close-up of tracks from (C), (H), and (M) is shown. The scale bar represents 300 nm. (E, J, and O) The mean diffusion coefficient of TCR interacting with various surfaces is shown. The diffusion coefficient was determined for each cell using the ensemble average MSD curve. n is the number of cells, and t is the number of tracks for each data set. The error bar represents the SD of the cell-to-cell variation. The p-value corresponds to the result of an unpaired two-sample t-test. To see this figure in color, go online.

TCR and CD45 are mobile on free surfaces

Although the T cell proteins were mobile at the apical surface of cells sitting on PLL, it is still possible that the interaction with the coated coverslip could alter the state of the cell, as happens during activation (29), which might manifest in a change in mobility of the proteins at the apical surface. We therefore also investigated the apical surface of cells resting on nonspecific bovine IgG and cells suspended in agarose away from the surface, wherein the environmental influence was expected to be near-minimal. In agarose, a standard triggering assay (34) based on the release of intracellular calcium indicated that the cells could be triggered normally when suspended in the gel (Fig. S8) by the addition of OKT3, implying that the cells were resting. In these conditions, the diffusion coefficient of the TCR (D = 0.068 ± 0.023 μm2/s) (Fig. 2 J; Video S4) was not statistically different from that on the apical surface of the cell resting on the coverslips coated with PLL (P = 0.06) and IgG (P = 0.23). Similar results were obtained for CD45 (see Table S1; Video S7). We therefore conclude that the presence of PLL completely alters protein diffusional properties at the basal cell surface (imaged by TIRFM), whereas the diffusion properties were unaffected on the apical surface (imaged by smLSM).

Protein immobilization by nonspecific IgG on glass surfaces is size-dependent

We also investigated the mobility of the TCR and CD45 on the basal surface of T cells sitting on nonspecific bovine IgG. Although this is presumed to be a “passive” surface that should show minimal interaction with proteins, previous measurements showed that this surface induces the local depletion of CD45 from regions of cellular interaction with the surface that we have called “close contacts” (10). TIRFM-based single-molecule measurements showed here that the overall diffusion of the TCR near the interface (Fig. 2 E) was not significantly influenced by the presence of the surface, as it was similar to that at the apical surface (D = 0.068 ± 0.021 μm2/s, P = 0.04). It should be noted, however, that the cells did not attach as vigorously to IgG-coated glass as they did to PLL, and the TCR moved in and out of the depth of field, which was consistent with the formation of undulating and/or discontinuous close contacts. It is possible that the bulk of the TCRs were free to diffuse because they were located outside of close contacts. In contrast to the TCR, the CD45 diffusion coefficient on the IgG-coated glass surface was significantly smaller than that on the apical surface (Fig. 2 O) measured by smLSM, which was consistent with CD45 interacting with the IgG-coated surface at a longer distance than the TCR. The sample data in Fig. 3 A (also see Video S8) show that mobile CD45 moves axially (based on the change in intensity) until it finally becomes static, presumably when it interacts with the surface (highest intensity). The spatial distribution of the mobile and immobile states was observable using the tracking analysis (Fig. 3 B; Video S6).

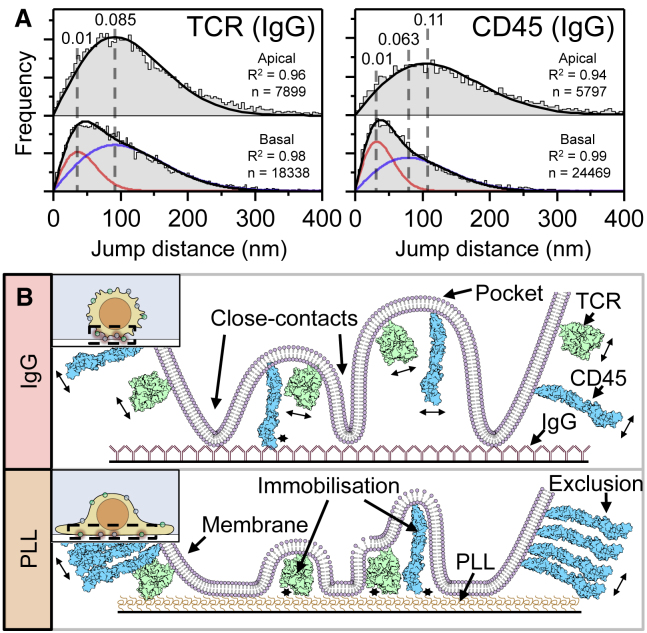

We further investigated the distribution of mobile and immobile states using JD analysis, which has been shown to be superior to MSD analysis when comparing small changes in diffusion coefficients (31), especially for short-track lengths. More importantly, JD is compatible with tracks that undergo changes in mobility, as we have shown in Fig. 3 A, and enables extraction of mobile and immobile populations that might not show up in MSD analysis. Fig. 4 A shows the JD distributions for the TCR and CD45 on the apical and basal surfaces of T cells resting on IgG-coated coverslips imaged by smLSM and TIRFM, respectively. On the apical surface, the fitted distributions were well described (R2 > 0.9) by a single diffusing population (see Table S2 for all conditions). The resulting diffusion coefficients were similar to those determined by MSD analysis (Table S1). This was not the case at the cell/IgG-interface that was imaged using TIRFM, where we observed shifts in the histogram that required two-component fits. This was most likely caused by the proteins interacting with the surface coating. JD analysis revealed that 75 ± 14% of the TCR population had a similar diffusion coefficient to that on the apical surface (D = 0.09 ± 0.02 μm2/s), whereas the rest was immobile (Fig. 4 A). We define “immobile” as anything below 0.01 μm2/s, based on diffusion measurements of TCRs in fixed cells on PLL (D = 0.01 μm2/s, 10 cells) that agree well with the fitted immobile populations (Fig. S9). This artificial motion appears to be due to sampling noise and potentially mechanical vibration, causing fixed molecules to appear as having an apparent diffusion coefficient. CD45, on the other hand, had a larger immobile population of 38 ± 14% (Fig. 4 A), likely because of the more extensive interactions of its larger extracellular domain with the surface. However, for the mobile fraction (D = 0.06 ± 0.04 μm2/s), the diffusion coefficient of CD45 was slower than that on the apical surface, which we also observed with MSD analysis (Fig. 2 O). The cartoon in Fig. 4 B summarizes the interactions observed on PLL and IgG. Although the Fabs increase the molecular weight of the TCR and CD45 by ∼10 and ∼20%, respectively, we do not expect the Fabs to influence the interactions between the studied proteins and the tested coatings because they bind near the membrane. UCHT-1 binds the two CD3-ε subunits that are part of the TCR complex (35). Gap 8.3 binds some part of the CD45d1-d4 region of CD45 (36), which does not include the 8–21-nm-long mucin-like region of CD45.

Figure 4.

(A) Normalized jump distance distributions for T cells interacting with IgG for data taken on the apical (smLSM) and basal (TIRFM) surfaces. Histograms were fitted with single or dual distributions, as described in Materials and Methods. The black line shows the sum of all fitted distributions, and the red and blue lines correspond to the slow and fast distributions, respectively. The dashed lines indicate the peak of each distribution, and the corresponding diffusion coefficient in μm2/s is given above each line. (B) A cartoon model of the influence of surface interactions on protein mobility is shown. Only the extracellular domains of the proteins are to scale, whereas other dimensions have been exaggerated for illustrative purposes. The podosomes of the T cell loosely sit on the nonspecific IgG surface (top), creating pockets in which proteins remain mobile (indicated by arrows). CD45 with its large extracellular domain is more likely to interact with the surface. The PLL surface (bottom) tightly binds the cell, excluding CD45 and immobilizing proteins (indicated by ∗) within the cell-PLL interface. The insets show cartoons of the cell topology. To see this figure in color, go online.

Most coated glass surfaces induce calcium signaling in T cells, unlike suspension in agarose

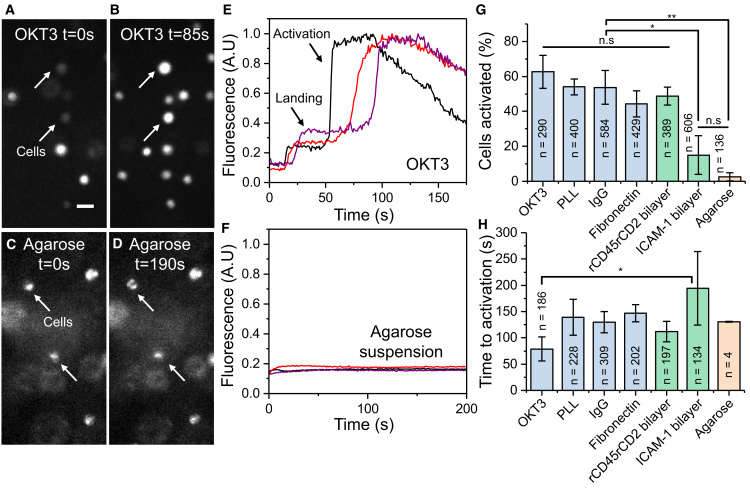

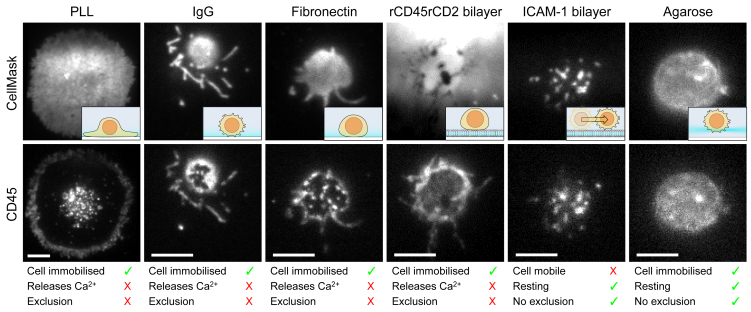

Having observed perturbation of TCR and CD45 dynamics by PLL- and IgG-coated coverslips, we attempted to find a better coating for studying resting T cells. Fibronectin-coated glass is reported to not induce T cell activation (37) and would enable TIRFM imaging. We found that membrane proteins on fibronectin (TCR: D = 0.058 ± 0.013 μm2/s; CD45: D = 0.057 ± 0.019 μm2/s) (Video S9) were mobile, unlike on PLL, while providing a suitable interface for imaging, unlike IgG. Also, CD45 appeared to be moving freely within the probed interface (Video S9). JD analysis showed that 25–30% of proteins on fibronectin were immobilized (Table S2), whereas most proteins remained mobile in agarose. These results indicated that the influence of fibronectin on TCR and CD45 dynamics was minimal compared to on PLL, pointing to the possibility that T cells may have a resting phenotype in this condition. However, the morphology of the cells was altered, presumably because of adhesion of membrane integrins to the fibronectin (38). We applied a calcium release assay (Fig. 5) using Fluo-4 (34) to determine whether IgG and fibronectin are indeed nonperturbative and found that, although superior to the PLL coating in terms of effects on TCR and CD45 diffusion, both IgG and fibronectin still caused a significant fraction of the cells to activate (Fig. 5 G) compared to the agarose gel. Although the time taken for calcium release to occur on PLL appears longer for IgG and fibronectin (Fig. 5 H) than for OKT3-coated coverslips (77 ± 21 s), the results were not statistically different. In terms of our choice of calcium assay, it could be argued that ratiometric calcium sensors such as Fura-2 are superior for monitoring subtle changes. However, we typically observed ∼4-fold increases in calcium, which were much larger than that observed for cells that did not activate (Fig. S10). We could clearly see the characteristic calcium response observed during T cell activation on all surfaces, showing that Fluo-4 is a suitable calcium probe for these experiments, as reported previously (34, 39).

Figure 5.

Surface-induced calcium flux varies greatly between supposedly resting surfaces. (A and B) A low magnification (15×) epifluorescence image shows Fluo-4-labeled Jurkat CD48+ T cells landing on an OKT3-coated coverslip at two time points. The arrows indicate individual cells that are initially weakly fluorescent (A) but, upon activation, undergo calcium release (B). The scale bar represents 20 μm. (C and D) A fluorescence image shows Fluo-4-labeled T cells suspended in agarose. Cells do not experience an increase in calcium as they remain resting in the gel. Out-of-focus cells appear larger and dimmer than others because of the three-dimensional distribution in the gel. (E) Representative examples are shown from (A) and (B) of activating cells. (F) Representative examples of cells remaining resting when suspended in an agarose gel are shown. (G) Fraction of cells activating within 5 min on supposedly resting surfaces. n represents the number of cells. Data were taken from three independent experiments for each condition. (H) The average time taken for activation for all activated cells is shown. ∗p < 0.01, ∗∗p < 0.001, n.s. p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA, and Tukey’s post hoc comparison. In (H), no significance (p < 0.05) was found except for between OKT3 and ICAM-1 bilayer, as reported. To see this figure in color, go online.

We then proceeded to investigate the possibility of using SLBs because of their ability to maintain membrane fluidity and their prevalent use in activation studies. Mobile anchors were required to adhere cells to the bilayers to facilitate imaging, as cells interacting with neat SLBs were found to roll around on the surface. Two anchors were tested: 1) a His-tagged chimeric protein comprising the extracellular domains rCD45rCD2 (estimated gap size of ∼29 nm), which could bind to Jurkat T cells that were transfected with a nonsignaling mutant form of rat CD48 (T92A) that binds rat CD2 with a comparable affinity to the human CD2-CD58 pair (∼20 μM), and 2) His-tagged ICAM-1 (estimated gap size of 40 nm), which could bind to LFA-1 integrin present on Jurkat T cells. The calcium assay showed that SLBs with rCD45rCD2 interacting with Jurkat (+CD48) resulted in significant calcium release, whereas the ICAM-1 SLBs greatly reduced calcium signaling (Fig. 5 G), although not to the extent of the agarose gel. We also measured the diffusion of TCR and CD45 on rCD45rCD2 SLBs (TCR: D = 0.044 ± 0.014 μm2/s; CD45: D = 0.064 ± 0.013 μm2/s), which was very similar to that on fibronectin. JD analysis showed that 23–29% of proteins were immobile (Table S2). We did not investigate ICAM-1 SLBs, as we found that the cells were highly mobile.

Reorganization of CD45 upon interaction with coated class surfaces

As membrane protein dynamics was preserved on fibronectin and on SLBs, we sought to understand the possible causes of the observed calcium signaling. Previous studies (10) have suggested that CD45 can be excluded on glass coated with PLL, nonspecific IgG, and SLBs carrying mobile anchors, leading to calcium signaling and ZAP70 recruitment. We applied two-color TIRFM imaging of CD45, labeled with saturating levels of Alexa Fluor 488-Fab and the membrane stain CellMask Deep Red to monitor CD45 exclusion, relative to the membrane, by coated glass surfaces (Fig. 6; Fig. S11). In all cases in which we observed significant calcium release (PLL, IgG, fibronectin, and rCD45rCD2 SLBs), we also noticed the exclusion of CD45 relative to the membrane dye within only 5 min of interaction. Note that the exclusion zones for cells interacting with IgG were often difficult to resolve because of the minimal adhesion. Compared to ICAM-1 SLBs, however, we could see rings of CD45 (yellow highlights in Fig. S11) that are characteristic of exclusion (10). On SLBs with ICAM-1, we found that the cells were mobile (Video S10) such that the coating is likely to maintain cells in their resting state, but this complicates the study of membrane protein dynamics and organization. smLSM imaging of CD45 and CellMask at the basal (bottom) plane of cells suspended in agarose (Fig. 6) showed minimal CD45 exclusion compared to cells interacting with coated surfaces. We verified that this observation was not simply a result of the imaging modality by directly comparing basal imaging of the CD45 distribution with TIRFM and smLSM (Video S3. Sample TIRFM Videos of TCR in Cells Resting on PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle, Compared with Imaging in Agarose, Right, Video S4. Sample smLSM Videos of TCR on the Apical Surface of Three Different T Cells Resting on Either PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle, and Suspended in Agarose, Right, Video S6. Sample TIRFM Videos of CD45 in Cells Resting on PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle Compared with Imaging in Agarose, Right, Video S7. Sample smLSM Videos of CD45 on the Apical Surface of Three Different T Cells Resting on Either PLL, Left, or IgG, Middle, and Suspended in Agarose, Right, Video S10. TIRFM Video of Membrane Stain CellMask Deep Red Showing How T Cell Microvilli Move around on ICAM-1 SLBs, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material A) and by imaging the basal and apical surfaces of the same cell (Fig. S12 B), which clearly showed that smLSM is capable of visualizing exclusion. To confirm that CD45 exclusion occurred relative to the TCR, we also imaged TCRs labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-Fab under saturating conditions. On PLL, we could observe TCRs throughout the contact area, but the distribution was inhomogeneous unlike the membrane stain, which was indicative of the clustering of TCRs (Fig. S13). However, we do not suggest that these are TCR microclusters, as the distribution was completely static, and we could not see any centripetal motion of clusters (Video S11).

Figure 6.

Supposedly resting surfaces alter the organization of CD45. Two-color TIRFM imaging of CellMask Deep Red membrane stain shows the distribution and topology of the cell membrane for Jurkat CD48+ cells upon interaction with various environments for 5 min. CD45 was labeled with saturating levels of Alexa Fluor 488-Fabs. The inset depicts a schematic of the cell morphology. Imaging was done in TIRFM mode except for the agarose case, for which smLSM was used. The rCD45rCD2 SLB has labeled mobile anchors, which somewhat disguises the membrane stain. The CD45 distribution shows large-scale reorganization compared to the membrane stain for PLL, IgG, fibronectin, and the rCD45rCD2 bilayer. The scale bar represents 5 μm. To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

The observations made by investigating the diffusional properties and organization of the TCR and CD45 using smLSM and TIRFM are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Perturbations by Coated Glass Surfaces

| PLL (TIRFM) | IgG (TIRFM) | Fibronectin (TIRFM) | rCD45rCD2 Bilayer (TIRFM) | ICAM-1 Bilayer (TIRFM) | Agarose (smLSM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCR diffusion | immobile | 75% mobile | 75% mobile | 71% mobile | – | freely |

| 25% immobile | 25% immobile | 29% immobile | diffusing | |||

| CD45 diffusion | 55% excluded | 62% mobile | 70% mobile | 77% mobile | – | freely |

| 45% immobile | 38% immobile | 30% immobile | 23% immobile | diffusing | ||

| Calcium signaling | 54.0% | 53.7% | 44.0% | 48.7% | 15.0% | 2.5% |

| 139 s | 130 s | 147 s | 112 s | 194 s | 131 s | |

| CD45 exclusion | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no |

| Cell mobility | immobilized | immobilized | immobilized | immobilized | mobile | immobilized |

PLL-coated glass completely immobilizes TCR and CD45 proteins in proximity to the surface. On IgG, the proteins are only partially immobilized, with CD45 having a larger immobile population. On the apical surface, both proteins diffuse freely, independent of coated coverslips or suspension in agarose. Fibronectin and rCD45rCD2 SLBs minimally influence protein dynamics compared to PLL while providing a suitable TIRFM interface, but these coatings influence cell morphology, induce calcium signaling, and exclude CD45. SLBs with ICAM-1 induce minimal calcium flux and CD45 exclusion but do not immobilize cells, which complicates imaging. Agarose suspension maintains protein mobility and organization while inducing minimal calcium signaling.

Both the TCR and CD45 were highly immobilized by contact with the PLL-coated glass. Previously, the TCR was shown to be partially immobilized on the PLL using confocal fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (21). Given the larger probe volume of confocal microscopy, it seems likely that the mobile population observed in those experiments was not associated with the cell surface. Single-molecule fluorescence measurements have also indicated immobilization of amebal proteins by glass (40) and of human proteins by PLL (41). Despite this, PLL has been a popular choice for studying “resting” T cells using TIRFM (9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 19, 23). The immobilization caused by PLL is likely explained by its electrostatic properties. The polyelectrolyte pulls the cell membrane toward the coverslip, creating a large interface that is tightly bound to the surface. Using both diffusion analysis and imaging, we observed that the tightly bound surface dramatically excludes CD45. Cells also adhered to lipid bilayers presenting nickel cations only, which also led to CD45 exclusion (Fig. S14). This effect could be suppressed by removing the nickelated lipids (or by blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin), whereupon the cells would “tumble” along the bilayer. These observations suggest that charge alone, in the form of PLL or nickelated lipids, suffices to elicit strong T cell adhesion.

On glass surfaces coated with passivating proteins (e.g., bovine IgG), a large fraction of the T cell proteins remained mobile, further confirming that the major effects of PLL are due to its charge. The largest difference between the two membrane proteins we studied on T cells interacting with IgG-coated glass was that there was a smaller fraction of mobile CD45 than TCR molecules. For use in diffusion-based studies, passivating coatings such as IgG appear to be less perturbative than PLL but present their own problems insofar as 1) the discontinuous contacts that form allow proteins to move in and out of focus and 2) the effects of the surface on mobility become dependent on the size of the extracellular domains of the proteins. Nevertheless, IgG also immobilized a significant fraction of TCR molecules and induced the local exclusion of CD45.

The differences in the behavior of the TCR and CD45 on PLL and IgG can be explained by considering that the TCR has a smaller extracellular domain than that of CD45: 8 nm vs. 21 nm, respectively (10). The Fabs used in this work each bind closely to the membrane and are therefore unlikely to affect surface interactions. A cartoon depicting the effects of the two surfaces on the proteins is shown in Fig. 4 B. The TCR exhibits a mostly homogenous distribution over the cell surface when the cell membrane binds tightly to the PLL-coated coverslip (Fig. 4 B, bottom), whereas CD45 is excluded, with only a few immobilized proteins remaining inside the contact. On IgG-coated glass, there is much less exclusion of either protein, as the weak interaction between the cell membrane and the surface appears to create pockets where the proteins can diffuse freely (Fig. 4 B, top). However, the large extracellular domain of CD45 makes it more likely to interact with the surface, as revealed by the observation that the immobile CD45 population is larger than that for the TCR.

The finding that PLL induces calcium influx in Jurkat cells is not completely surprising given that the strong adhesion of the cells to PLL-coated surfaces leads to CD45 exclusion (Figs. 6, S11; Video S12), which suffices to initiate signaling (10). However, the extent to which an immortal cell line like Jurkat is representative of primary cells is questionable. Although continuously cycling cells probably cannot be considered to be truly “resting,” we would nevertheless expect primary cells to exhibit similar immobilization, exclusion, and calcium responses on PLL given that similar effects are observed when they interact with IgG-coated coverslips and adhesion-molecule-presenting bilayers (10). Contrary to the interactions we observed here for Jurkat T cells on PLL-coated glass, the effects of apparently less adhesive coatings like IgG (Video S12), fibronectin, and rCD45rCD2 SLBs on signaling can perhaps be explained in terms of the behavior of T cell microvilli (26, 42, 43). These actin-rich protrusions continually push against surfaces in their effort to search for antigens. It is possible that the microvilli push with sufficient force to exclude CD45, thereby potentiating calcium signaling. For glass coated with ICAM-1, the relatively large gap between the cell and the surface (∼40 nm) combined with both the incomplete attachment and fluidity of the bilayer might prevent microvilli from forming (large or stable enough) CD45 exclusion zones that can initiate calcium signaling. For agarose gel, the elasticity is comparable to the cell membrane (∼38 kPa (44) vs. 5–11 kPa (45)), which might be less perturbative in response to the forces and motion exerted by the microvilli. Whether or not these processes in turn affect global protein mobility is unclear, although activation is associated with large-scale reorganization and clustering of the TCR (29). As shown here, diffusion on the apical surface was largely unaffected by surface coating, suggesting that surfaces mostly induce local rather than global changes in mobility on the timescales studied here. Nevertheless, the immobilization, slowing down, and exclusion of proteins can influence signaling (10), making it important to be able to visualize molecular behavior in unperturbed cells, e.g., suspended in agarose above the surface and visualized using smLSM, as done here.

Fibronectin was found to be only slightly superior to both PLL and IgG in terms of its influence on TCR and CD45 dynamics. The kinase Lck, which has previously been shown to reside in nanoclusters on PLL-coated surfaces (9), is unclustered on fibronectin (37). However, we observed CD45 exclusion and calcium signaling on fibronectin-coated glass, indicating that this surface is also unsuitable for imaging resting T cells. SLBs presenting the mobile adhesion protein rCD45rCD2 also caused partial immobilization of proteins, CD45 exclusion, and calcium signaling despite the likely creation of a large gap between the surface and the cell (∼29 nm). Therefore, even the use of large mobile anchors fails to secure the resting state. We found that the least perturbative surfaces comprised SLBs presenting ICAM-1. This coating has been used for numerous activation studies (22, 46, 47), and our results here suggest that the coating is minimally perturbative. However, the high mobility of cells on SLBs coated with ICAM-1, presumably due to the lack of calcium signaling, complicates its use for imaging resting T cells. Although it is conceivable that glass surfaces could be optimized in some way to prevent calcium release in the future, we suggest that, for now, cells should ideally be studied in suspension if the aim of the experiment is to image live, resting lymphocytes.

In our analysis, we considered the diffusion of membrane proteins to be two-dimensional along the surface of an idealized sphere such that the images acquired using the light sheet represent a two-dimensional projection of the spherical surface. Neglecting the effects of the projection causes at most a 35% reduction in the perceived diffusion coefficient at the equator of the sphere (48), which is proved via simulations (Supporting Materials and Methods and Fig. S15). Furthermore, the surface can effectively be approximated by a plane, as only the top ∼1–2 μm of the cell is imaged by the light sheet. However, this treatment neglects the fact that cell membranes are highly irregular. This is particularly true for T cells, which feature actin-rich structures, such as microvilli and podosomes (26, 42). Therefore, proteins diffuse perpendicularly to the membrane surface, causing the observed diffusion to be slower than the actual value (49). We could observe this irregular structure using smLSM by imaging at the central position of the cell (Fig. S16). Three-dimensional tracking methods (50) could be used to resolve this problem and to measure the true mobility of membrane proteins on unperturbed surfaces, which we have begun to apply to T cells (51).

In conclusion, we have shown that membrane protein dynamics and organization are greatly influenced by interactions with surfaces used to immobilize cells for imaging, leading to calcium signaling. These findings suggest that T cells immobilized on coated coverslips will be perturbed from their resting state. If the goal is to image resting T cells, which is crucial to detect the early events that lead to T cell activation, surfaces should ideally be avoided altogether. smLSM of cells suspended in agarose gels allows single-molecule imaging to be performed on live, resting T cells and should be broadly applicable to other cell types.

Author Contributions

A.P., J.M., A.M.S., S.J.D., D.K., and S.F.L. designed the research. A.P. implemented the light-sheet microscope and performed diffusion and imaging experiments. A.P., J.M., and A.M.S. performed the calcium experiments. A.P. and A.R.C. analyzed the data. A.P., K.K., and A.L. prepared and performed the bilayer experiments. A.P., S.J.D., D.K., and S.F.L. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Royal Society University Research Fellowship (UF120277 to S.F.L.) and a Research Professorship (RP150066 to D.K.); the EPSRC (EP/L027631/1 to A.P.); and the Wellcome Trust (098274/Z/12/Z to S.J.D.).

Editor: Julie Biteen.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, sixteen figures, two tables, and twelve videos are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(18)30396-5.

Contributor Information

Simon J. Davis, Email: simon.davis@imm.ox.ac.uk.

David Klenerman, Email: dk10012@cam.ac.uk.

Steven F. Lee, Email: sl591@cam.ac.uk.

Supporting Citations

References (52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58) appear in Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The schematic on the top indicates the excitation method and position of the light sheet, which is scanned from the bottom to the top of the cell. TCR is immobile at the basal surface and mobile on the apical surface. The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The TCR is expressed with a HaloTag protein that is labeled with silicon rhodamine.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The protein is initially dim and mobile. As it interacts with the surface (becomes brighter), it becomes immobilized. The tracks represent +-5 frames. The scale bar is 1 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz. Visualization was performed with the Trackmate plugin for ImageJ.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 2 μm, the exposure time is 600 ms, the frame rate is 1 Hz, and the playback rate is 6x real-time.

TCR is labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-Fabs under saturating conditions. The scale bar is 2 μm, the exposure time is 100 ms, the frame rate is 1 Hz, and the playback rate is 10x real-time.

CD45 is labelled with Alexa Fluor 488-Fabs under saturating conditions, and the membrane is labelled with CellMask deep red. The scale bar is 5 μm, the exposure time is 200 ms, the frame rate is 1 Hz, and the playback rate is 10x real-time.

References

- 1.Dustin M.L., Depoil D. New insights into the T cell synapse from single molecule techniques. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:672–684. doi: 10.1038/nri3066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Merwe P.A., Dushek O. Mechanisms for T cell receptor triggering. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011;11:47–55. doi: 10.1038/nri2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis S.J., van der Merwe P.A. The kinetic-segregation model: TCR triggering and beyond. Nat. Immunol. 2006;7:803–809. doi: 10.1038/ni1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermiston M.L., Xu Z., Weiss A. CD45: a critical regulator of signaling thresholds in immune cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:107–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.140946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglass A.D., Vale R.D. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell. 2005;121:937–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drbal K., Moertelmaier M., Schütz G.J. Single-molecule microscopy reveals heterogeneous dynamics of lipid raft components upon TCR engagement. Int. Immunol. 2007;19:675–684. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunne P.D., Fernandes R.A., Klenerman D. DySCo: quantitating associations of membrane proteins using two-color single-molecule tracking. Biophys. J. 2009;97:L5–L7. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James J.R., White S.S., Klenerman D. Single-molecule level analysis of the subunit composition of the T cell receptor on live T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17662–17667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700411104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossy J., Owen D.M., Gaus K. Conformational states of the kinase Lck regulate clustering in early T cell signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:82–89. doi: 10.1038/ni.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang V.T., Fernandes R.A., Davis S.J. Initiation of T cell signaling by CD45 segregation at ‘close contacts’. Nat. Immunol. 2016;17:574–582. doi: 10.1038/ni.3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lillemeier B.F., Pfeiffer J.R., Davis M.M. Plasma membrane-associated proteins are clustered into islands attached to the cytoskeleton. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18992–18997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609009103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lillemeier B.F., Mörtelmaier M.A., Davis M.M. TCR and Lat are expressed on separate protein islands on T cell membranes and concatenate during activation. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:90–96. doi: 10.1038/ni.1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sherman E., Barr V., Samelson L.E. Functional nanoscale organization of signaling molecules downstream of the T cell antigen receptor. Immunity. 2011;35:705–720. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pageon S.V., Cordoba S.P., Davis D.M. Superresolution microscopy reveals nanometer-scale reorganization of inhibitory natural killer cell receptors upon activation of NKG2D. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:ra62. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larghi P., Williamson D.J., Hivroz C. VAMP7 controls T cell activation by regulating the recruitment and phosphorylation of vesicular Lat at TCR-activation sites. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:723–731. doi: 10.1038/ni.2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maity P.C., Blount A., Reth M. B cell antigen receptors of the IgM and IgD classes are clustered in different protein islands that are altered during B cell activation. Sci. Signal. 2015;8:ra93. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roh K.H., Lillemeier B.F., Davis M.M. The coreceptor CD4 is expressed in distinct nanoclusters and does not colocalize with T-cell receptor and active protein tyrosine kinase p56lck. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E1604–E1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503532112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin-Delanchy P., Burn G.L., Owen D.M. Bayesian cluster identification in single-molecule localization microscopy data. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:1072–1076. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pageon S.V., Tabarin T., Gaus K. Functional role of T-cell receptor nanoclusters in signal initiation and antigen discrimination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E5454–E5463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607436113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oszmiana A., Williamson D.J., Davis D.M. The size of activating and inhibitory killer Ig-like receptor nanoclusters is controlled by the transmembrane sequence and affects signaling. Cell Reports. 2016;15:1957–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James J.R., McColl J., Davis S.J. The T cell receptor triggering apparatus is composed of monovalent or monomeric proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:31993–32001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manz B.N., Jackson B.L., Groves J. T-cell triggering thresholds are modulated by the number of antigen within individual T-cell receptor clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9089–9094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018771108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman S.A., Goyette J., Grinstein S. Integrins form an expanding diffusional barrier that coordinates phagocytosis. Cell. 2016;164:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Y., Pandzic E., Gaus K. An intermolecular FRET sensor detects the dynamics of T cell receptor clustering. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15100. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huppa J.B., Axmann M., Davis M.M. TCR-peptide-MHC interactions in situ show accelerated kinetics and increased affinity. Nature. 2010;463:963–967. doi: 10.1038/nature08746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jung Y., Riven I., Haran G. Three-dimensional localization of T-cell receptors in relation to microvilli using a combination of superresolution microscopies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E5916–E5924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605399113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans R., Lellouch A.C., Hogg N. The integrin LFA-1 signals through ZAP-70 to regulate expression of high-affinity LFA-1 on T lymphocytes. Blood. 2011;117:3331–3342. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S.A., Ponjavic A., Biteen J.S. Nanoscopic cellular imaging: confinement broadens understanding. ACS Nano. 2016;10:8143–8153. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b02863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu Y.S., Cang H., Lillemeier B.F. Superresolution imaging reveals nanometer- and micrometer-scale spatial distributions of T-cell receptors in lymph nodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:7201–7206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512331113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James J.R., Vale R.D. Biophysical mechanism of T-cell receptor triggering in a reconstituted system. Nature. 2012;487:64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature11220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weimann L., Ganzinger K.A., Klenerman D. A quantitative comparison of single-dye tracking analysis tools using Monte Carlo simulations. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tinevez J.Y., Perry N., Eliceiri K.W. TrackMate: an open and extensible platform for single-particle tracking. Methods. 2017;115:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Favier B., Burroughs N.J., Valitutti S. TCR dynamics on the surface of living T cells. Int. Immunol. 2001;13:1525–1532. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.12.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fritzsche M., Fernandes R.A., Eggeling C. CalQuo: automated, simultaneous single-cell and population-level quantification of global intracellular Ca2+ responses. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:16487. doi: 10.1038/srep16487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnett K.L., Harrison S.C., Wiley D.C. Crystal structure of a human CD3-ε/δ dimer in complex with a UCHT1 single-chain antibody fragment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:16268–16273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407359101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Streuli M., Morimoto C., Saito H. Characterization of CD45 and CD45R monoclonal antibodies using transfected mouse cell lines that express individual human leukocyte common antigens. J. Immunol. 1988;141:3910–3914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumgart F., Arnold A.M., Schütz G.J. Varying label density allows artifact-free analysis of membrane-protein nanoclusters. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:661–664. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doucey M.A., Legler D.F., Luescher I.F. The β1 and β3 integrins promote T cell receptor-mediated cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:26983–26991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anikeeva N., Grosso D., Sykulev Y. Evaluating frequency and quality of pathogen-specific T cells. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13264. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee J., Miyanaga Y., Hohng S. Video-rate confocal microscopy for single-molecule imaging in live cells and superresolution fluorescence imaging. Biophys. J. 2012;103:1691–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez J.B., Segura J.M., Vogel H. Monitoring the diffusion of single heterotrimeric G proteins in supported cell-membrane sheets reveals their partitioning into microdomains. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;363:918–930. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sage P.T., Varghese L.M., Carman C.V. Antigen recognition is facilitated by invadosome-like protrusions formed by memory/effector T cells. J. Immunol. 2012;188:3686–3699. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cai E., Marchuk K., Krummel M.F. Visualizing dynamic microvillar search and stabilization during ligand detection by T cells. Science. 2017;356:eaal3118. doi: 10.1126/science.aal3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Normand V., Lootens D.L., Aymard P. New insight into agarose gel mechanical properties. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1:730–738. doi: 10.1021/bm005583j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu M., Wang J., Cai J. Nanostructure and nanomechanics analysis of lymphocyte using AFM: from resting, activated to apoptosis. J. Biomech. 2009;42:1513–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaizuka Y., Douglass A.D., Vale R.D. The coreceptor CD2 uses plasma membrane microdomains to transduce signals in T cells. J. Cell Biol. 2009;185:521–534. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hashimoto-Tane A., Sakuma M., Saito T. Micro-adhesion rings surrounding TCR microclusters are essential for T cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:1609–1625. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oswald F., Varadarajan A., Bollen Y.J. MreB-dependent organization of the E. coli cytoplasmic membrane controls membrane protein diffusion. Biophys. J. 2016;110:1139–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adler J., Shevchuk A.I., Parmryd I. Plasma membrane topography and interpretation of single-particle tracks. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:170–171. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0310-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson M.A., Casolari J.M., Moerner W.E. Three-dimensional tracking of single mRNA particles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using a double-helix point spread function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:17864–17871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012868107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carr A.R., Ponjavic A., Lee S.F. Three-dimensional super-resolution in eukaryotic cells using the double-helix point spread function. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1444–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Axelrod D. Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in cell biology. Traffic. 2001;2:764–774. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.21104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ritter J.G., Veith R., Kubitscheck U. Light sheet microscopy for single molecule tracking in living tissue. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruns T., Schickinger S., Schneckenburger H. Preparation strategy and illumination of three-dimensional cell cultures in light sheet-based fluorescence microscopy. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012;17:101518. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.10.101518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hennig S., van de Linde S., Sauer M. Instant live-cell super-resolution imaging of cellular structures by nanoinjection of fluorescent probes. Nano Lett. 2015;15:1374–1381. doi: 10.1021/nl504660t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krieger J.W., Singh A.P., Wohland T. Imaging fluorescence (cross-) correlation spectroscopy in live cells and organisms. Nat. Protoc. 2015;10:1948–1974. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2015.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tokunaga M., Imamoto N., Sakata-Sogawa K. Highly inclined thin illumination enables clear single-molecule imaging in cells. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:159–161. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Crocker J.C., Grier D.G. Methods of digital video microscopy for colloidal studies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1996;179:298–310. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The schematic on the top indicates the excitation method and position of the light sheet, which is scanned from the bottom to the top of the cell. TCR is immobile at the basal surface and mobile on the apical surface. The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The TCR is expressed with a HaloTag protein that is labeled with silicon rhodamine.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The protein is initially dim and mobile. As it interacts with the surface (becomes brighter), it becomes immobilized. The tracks represent +-5 frames. The scale bar is 1 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz. Visualization was performed with the Trackmate plugin for ImageJ.

The scale bar is 5 μm, and the frame rate is 20 Hz.

The scale bar is 2 μm, the exposure time is 600 ms, the frame rate is 1 Hz, and the playback rate is 6x real-time.

TCR is labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-Fabs under saturating conditions. The scale bar is 2 μm, the exposure time is 100 ms, the frame rate is 1 Hz, and the playback rate is 10x real-time.

CD45 is labelled with Alexa Fluor 488-Fabs under saturating conditions, and the membrane is labelled with CellMask deep red. The scale bar is 5 μm, the exposure time is 200 ms, the frame rate is 1 Hz, and the playback rate is 10x real-time.