Abstract

The effect of no- and reduced tillage (NT/RT) on greenhouse gas (GHG) emission was highly variable and may depend on other agronomy practices. However, how the other practices affect the effect of NT/RT on GHG emission remains elusive. Therefore, we conducted a global meta-analysis (including 49 papers with 196 comparisons) to assess the effect of five options (i.e. cropping system, crop residue management, split application of N fertilizer, irrigation, and tillage duration) on the effect of NT/RT on CH4 and N2O emissions from agricultural fields. The results showed that NT/RT significantly mitigated the overall global warming potential (GWP) of CH4 and N2O emissions by 6.6% as compared with conventional tillage (CT). Rotation cropping systems and crop straw remove facilitated no-tillage (NT) to reduce the CH4, N2O, or overall GWP both in upland and paddy field. NT significantly mitigated the overall GWP when the percentage of basal N fertilizer (PBN) >50%, when tillage duration > 10 years or rainfed in upland, while when PBN <50%, when duration between 5 and 10 years, or with continuous flooding in paddy field. RT significantly reduced the overall GWP under single crop monoculture system in upland. These results suggested that assessing the effectiveness of NT/RT on the mitigation of GHG emission should consider the interaction of NT/RT with other agronomy practices and land use type.

Introduction

Agriculture is a main source of anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1], contributing 47% and 76% of CH4 and N2O emissions, respectively. Agricultural practices (e. g. soil tillage, fertilizer, and irrigation) play an important role in regulating the microbial process of CH4 and N2O production in agricultural soil [2]. Detailed knowledge of the effects of agronomical options on GHG emissions is imperative for the recommendation of low emission practices.

Reduced (RT) and no tillage (NT) are widely recommended in world crop production to improve soil structure, reduce soil erosion, and enhance soil organic matter as compared with conventional tillage (CT). However, the effect of NT/RT on climate change mitigation has been intensively debated because of the substantial inconsistency in individual field experiments [3–5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that NT significantly reduced [6], increased [7] or did not affect [8] CH4 emission from soil, compared with that of CT. Similarly, a decrease [9], increase [10], or insignificant change [11] of N2O emission was observed in response to NT. In addition, the effects of NT on CH4 and N2O emissions were usually inconsistency. For instance, a previous study reported that NT significantly reduced CH4 emission in paddy field compared with CT, but increased N2O emission [12]. Similarly in the uplands, NT significantly reduced not only N2O emission but also CH4 uptake [13]. The trade-off relationship may offset the effect of NT on GHG mitigation. The highly diverse results from individual studies are unlikely to reveal a general pattern of soil tillage on GHG mitigation. Although some studies have been conducted to evaluate the effect of NT or RT on GHG mitigation, they focused only on CH4 or N2O emissions [14–15]. The integrated effects of RT or NT on the total GWP of CH4 and N2O emissions has not been well documented.

Soil tillage can affect several soil properties (e.g. soil bulk density, temperature, moisture, and the vertical distribution of crop residue) that influence the production and emission processes of CH4 and N2O [16–18]. Even more complicatedly, some effects of tillage on CH4 and N2O emissions function in potentially contrasting ways, making it difficult to predict the effect of a tillage practice on GHG mitigation [14,19]. For example, in paddy fields, NT can increase CH4 oxidation by improving the soil structure and decreasing the disturbance on the niche of the Methanogenic bacteria [20–21]; whereas, NT tended to increase the soil organic matter, which facilitated the increase in CH4 emission [22]. The integrated effect of NT on CH4 and N2O emissions was highly dependent on the climatic conditions, soil properties, and agricultural practices. Van Kessel et al. [14] reported that dry climatic conditions were conducive for NT/RT to reduce N2O emission based on a global meta-analysis of NT/RT on N2O emission in uplands. Zhao et al. [15] reported that the inhibition effects of NT on CH4 or N2O emissions were negatively correlated with temperature, precipitation, and soil pH by synthesizing the experimental results in China. Besides the climate and soil factors, the interaction of tillage with other agronomy options on CH4 and N2O emissions was also observed in previous field experiments [23–24]. Van Kessel et al. [14] assessed the interaction of fertilizer application depth with tillage and reported that NT/RT performed better on the mitigation of N2O emission when N fertilizer was placed ≥5cm rather than < 5cm. However, the interaction effect of other options (e.g., cropping system and irrigation) with NT/RT is still unclear. A better understanding of the interaction of agronomy practices with NT/RT will be beneficial to determining the best management practices for NT/RT to mitigate CH4 and N2O emissions in agricultural fields.

Therefore, the main objectives of this meta-analysis were: 1) to quantitatively summarize the effects of NT/RT on the total GWP of CH4 and N2O emissions and 2) to investigate the effects of cropping system, crop residue management, fertilizer split application, irrigation and tillage duration on the effectiveness of NT/RT.

Materials and methods

Data sources

We conducted a literature survey of peer-reviewed papers published before December 2016 that reported the effects of NT/RT on both CH4 and N2O emissions using Google Scholar and ISI-Web of Science. The preferred reporting items for system review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig 1) have been followed for data collection and analysis. The keywords used in literature search were “soil tillage”, “no-tillage”, “reduced tillage”, “CH4”, “N2O”, and “greenhouse gas emission”. The following 3 criteria were used to select appropriate paired experiments: (1) the NT/RT and CT plots must be conducted at the same site with the same crop, agronomic management options (e.g., fertilizer, irrigation,), and experiment duration; (2) CH4 and N2O fluxes were both measured by using statistic chamber methods in field conditions for an entire crop growing season; and (3) the N application rate, crop straw returning methods, experimental duration, and water management practices were clearly recorded. Forty-nine studies including 196 comparisons (Table 1) were collected according to these criteria. The experiment sites covered 7 countries (USA, Brazil, China, Japan, Mexico, Philippines and Spain). The land use types in selected studies were primarily paddy field and upland. The crops included rice, wheat, maize, soybeans, barley, oats, and vetch. RT consisted of rotary tillage, zone tillage, shallow plowing, precision tillage, and subsurface tillage. The detailed information of selected studies and collected data is listed in the support information (Table A in S1 Appendix).

Fig 1. The PRISMA (preferred reporting items for system review and meta-analysis) guidelines used for the collection and meta-analysis of data.

Table 1. The studies used in the meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of NT/RT on CH4 and N2O emissions.

| ID | Crop | Country | Number of comparisons | Tillage methods | Reference | ID | Crop | Country | Number of comparisons | Tillage methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wheat, pea | China | 4 | NT | [25] | 26 | Rice | China | 2 | RT | [45] |

| 2 | Rice | China | 4 | NT, RT | [26] | 27 | Rice | China | 2 | NT | [12] |

| 3 | Rice | China | 2 | NT | [27] | 28 | Rice | Brazil | 1 | NT | [46] |

| 4 | Rice | China | 8 | RT | [28] | 29 | Rice | Japan | 2 | NT, RT | [6] |

| 5 | Rice | China | 4 | RT | [7] | 30 | Maize | America | 2 | NT | [47] |

| 6 | Wheat | Spain | 2 | NT, RT | [9] | 31 | Wheat | Japan | 3 | RT | [48] |

| 7 | Wheat, maize | China | 6 | NT, RT | [29] | 32 | Wheat | America | 4 | NT, RT | [16] |

| 8 | Rice | China | 8 | NT | [30] | 33 | Wheat | America | 2 | NT, RT | [49] |

| 9 | Wheat | China | 1 | NT | [31] | 34 | Barley, vetch | Spain | 4 | NT, RT | [50] |

| 10 | Barley, Soybean | Japan | 8 | NT | [32] | 35 | Wheat, Maize | China | 6 | NT, RT | [51] |

| 11 | Rice | Philippines | 2 | NT | [33] | 36 | Wheat | China | 1 | RT | [52] |

| 12 | Barley | America | 16 | NT | [11] | 37 | Rice | China | 2 | NT | [53] |

| 13 | Rice | Brazil | 3 | NT | [34] | 38 | Wheat, pea | China | 6 | NT | [54] |

| 14 | Maize | China | 4 | NT, RT | [35] | 39 | Rye | Spain | 1 | NT | [55] |

| 15 | Wheat | China | 4 | NT | [36] | 40 | Rice | Spain | 3 | NT | [56] |

| 16 | Rice | China | 2 | NT, RT | [37] | 41 | Rice | China | 16 | NT | [57] |

| 17 | Wheat | China | 2 | NT | [38] | 42 | Rice | China | 2 | NT | [23] |

| 18 | Wheat | China | 8 | NT, RT | [39] | 43 | Rice | India | 2 | NT | [58] |

| 19 | Rice | China | 2 | RT | [40] | 44 | Rice | Japan | 4 | RT | [59] |

| 20 | Wheat | China | 4 | NT, RT | [41] | 45 | Vegetable | Japan | 5 | NT | [60] |

| 21 | Barley | America | 6 | NT | [13] | 46 | Vetch | Spain | 2 | NT, RT | [61] |

| 22 | Maize | Mexico | 2 | RT | [42] | 47 | Bioenergy crop | China | 2 | NT | [62] |

| 23 | Oat | China | 3 | NT | [43] | 48 | Wheat, pea | China | 4 | NT | [63] |

| 24 | Wheat, pea | China | 4 | NT | [44] | 49 | Rice | China | 1 | NT | [64] |

| 25 | Maize, soybean | America | 8 | NT, RT | [10] |

The results of CH4 and N2O emissions were converted into global warming potential (GWP) by multiplying the 100-year radiative forcing potential coefficients to CO2 (25 and 298 used for CH4 and N2O, respectively). Considering that upland and paddy fields showed a great difference in CH4 and N2O emissions, we examined the effect of NT/RT on GHG emissions for these two land use types separately.

Five agronomic practices, including cropping system, residue management, N split, irrigation, and tillage duration, were analyzed. Cropping system was categorized into single crop monoculture system and double crops rotation system for upland, and rice-upland crop rotation and double rice for paddy field, referred to the crop sequences in a whole year. Residue management practices were categorized as crop straw remove and return. We further analyzed the effects of N split methods on the effect of NT/RT. N split methods were categorized into four groups based on the percentage of basal N fertilizer (PBN = 100%, 50% < PBN < 100%, PBN = 50%, and PBN < 50%; PBN = basal N rate / total N rate *100). Irrigation practices were divided into rain-fed and irrigation for uplands, and continuous flooding and intermittent irrigation for paddy fields. Tillage duration was divided into three levels: short-term 1–5 years; medium-term 5–10 years; and long-term >10 years.

Data analysis

The response ratio (R) was used to compare the CH4, N2O and overall GWP under NT/RT and CT. The natural log of R was used as the effect size, which was calculated by following equation:

| (1) |

Where, XNT/RT and XCT are the amounts of CH4, N2O and overall GWP under NT/RT and CT, respectively.

This meta-analysis was performed by using a nonparametric weighting function and the confidence intervals (CIs) were generated by using bootstrapping [14]; because only 22.4% of selected studies reported the standard deviation or error of CH4, N2O and GWP. Effect size was weighted by the number of experiment replicates and the number of CH4 and N2O flux measurements per month.

| (2) |

Where, W is the weight factor, n is the number of experiment replicates; and f is the number of CH4 and N2O flux measurements per month. This weighting approach assigned more weight to field experiments that were well replicated.

The mean effect size was calculated from lnR of individual studies by:

| (3) |

Where, w(i) is the weighting factor estimated by formula (2). To ease interpretation, the mean effect size was back-transformed and reported as the percent change of NT/RT relative to that of CT.

The Mean effect size, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), group heterogeneity and publication bias were calculated by MetaWin 2.1[65]. The random-effects model was used in the calculation of mean effect sizes, based on the assumption that random variation in GHG emissions occurred between observations. The 95% CIs around mean effect sizes were calculated by using bootstrapping with 4999 iterations [66]. The mean effect sizes were considered to be significantly different if their 95% CIs did not overlap. P-values for differences between categories of studies (Table 2) were calculated using resampling tests [14]. The publication bias was checked using Rank Correlation Test method (Kendall's tau and Spearman rank-order correlation). For the categories existing publication bias, a bias corrected CI was used instead of bootstrap CI.

Table 2. The group heterogeneity of categorical variables (NT/ RT, P-value).

| Categorical variable | CH4 | N2O | GWP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upland | Crop rotation | 0.157/ 0.643 | 0.005/ 0.193 | 0.136/ 0.012 |

| residue management | 0.606 / 0.751 | 0.310 / 0.797 | 0.392 / 0.508 | |

| N split | 0.907/ 0.140 | 0.213/ 0.569 | 0.133/ 0.293 | |

| Irrigation | 0.446/ 0.082 | 0.698/ 0.564 | 0.690/ 0.178 | |

| tillage duration | 0.293/ 0.008 | 0.006/ 0.619 | <0.001/ 0.922 | |

| Rice paddy | Crop rotation | 0.330/ 0.353 | 0.053/ 0.584 | 0.073/ 0.232 |

| residue management | 0.137/ 0.055 | 0.939/ 0.166 | 0.097/ 0.015 | |

| N split | 0.003/ 0.424 | 0.943/ 0.492 | 0.005/ 0.544 | |

| Irrigation | 0.036/ NA | 0.076/ NA | 0.010/ NA | |

| tillage duration | 0.231/ 0.004 | 0.148/ 0.616 | 0.101/ 0.019 |

P-values in bold indicate significance (P < 0.05). “NA” means not available

Results and discussion

Overall effect

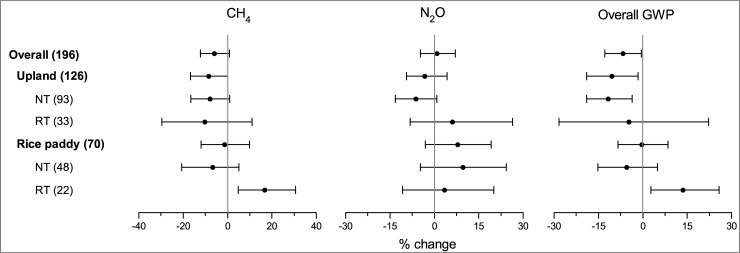

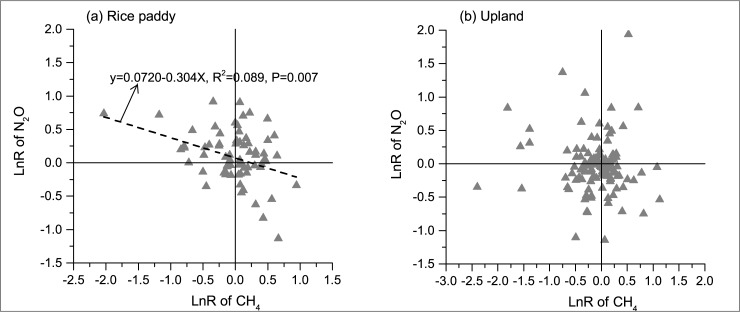

Overall, reduced tillage system (NT/RT) did not exhibit significant effects on CH4 and N2O emissions as compared with CT (Fig 2). However, their effects on the overall GWP of CH4 and N2O emissions was marginally significant. The overall GWP was mitigated by 6.6% by NT/RT as compared with CT. The performance of NT/RT depended on land use type and tillage methods. In rice paddies, a trade-off relationship existed in the effects of NT/RT on CH4 and N2O emissions (Fig 3(A)). NT tended to mitigate the CH4 emission, whereas it increased the N2O emission, resulting in no significant impact on the overall GWP in rice paddies (Fig 2). However, RT significantly increased the CH4 emission and overall GWP compared with CT. The poor performance of RT in the inhibition of CH4 emission was possibly attributed to its weaker effect on reducing CH4 production than that of CT and weaker effect on increasing CH4 oxidation than that of NT. CT incorporated crop residue into deeper soil than RT, reducing the decomposition of these residues through the protection of the soil matrix [7]. Lower soil disturbance and a shallower CH4 oxidation zone for NT than RT were conducive to improving CH4 oxidation [37, 48].

Fig 2. The overall effects of reduced tillage system on CH4, N2O and overall GWP.

Fig 3. The relationship of the LnR of NT/RT on CH4 and N2O emissions in paddy and upland fields.

Unlike that of rice paddies, upland soil usually absorbed CH4 from the atmosphere through the microbial process of CH4 oxidation by methanotrophs [67]. The effect of NT/RT on CH4 uptake did not show an obvious relationship with its impact on N2O emission (Fig 3(B)). The overall GWP was reduced 11.6% by NT as compared with CT (Fig 2). Whereas the effects of RT on CH4 uptake, N2O emission and overall GWP were not significant.

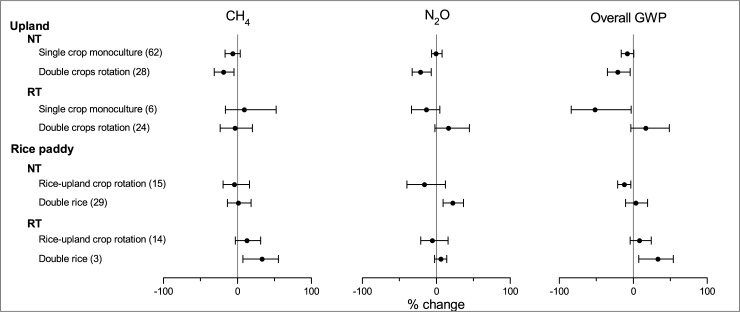

Impact of cropping system

NT significantly reduced CH4 uptake, N2O emission, and overall GWP by 18.4%, 21.0% and 20.8% under the double crops rotation system, respectively, whereas its effects was not significant under the single crop monoculture system (Fig 4). The effects of cropping systems on CH4 and N2O emissions after adopting NT may primarily attribute to the variability in the quantity of aboveground crop residues and roots in soil profile. Increasing in cropping frequency and crop diversity, such as double crops rotation, can produce more residues and roots than that of single crop monoculture system. Most of the crops in the double crops rotation system of this analysis were cereals crops (such as maize, wheat, and barley) with high C:N ratio. The decomposition of crop residues with high C:N ratio could stimulated microbial N immobilization in soil, thus reduce the available N for N2O production [68]. Additionally, the decomposition of crop residues also consumed sizable O2 in soil pores, which may inhibit the CH4 oxidation [69]. RT significantly reduced the overall GWP of CH4 and N2O by 20.8% under the single crop monoculture system, as compared with CT (Fig 4). However, its effect on the overall GWP was not significant under the double crops rotation system. The upland field was usually tilled once in one year under the monoculture system; but usually two times per year under the rotation system. Less tillage operation could reduce the disturbance to methanotrophic microbes and enhance CH4 uptake [9]. Less tillage operation could also prevent soil aggregates and inhibit organic N mineralization, which is beneficial to the mitigation of N2O production [68].

Fig 4. Impact of cropping system on the effects of NT and RT on CH4, N2O and overall GWP.

As in the paddy fields, NT significantly reduced the overall GWP by its cumulative abatement on CH4 and N2O emissions (Fig 4) under the rice-upland crops rotation system; whereas its effect was not significant on the overall GWP under double rice system. A previous study has reported that soils with higher water contents during the annual crop growing season produced more CH4 because of their higher methanogenic populations and activities [70]. The annual flooding time was less for the rice-upland crop rotation system than the double rice system. The rotation of upland crop could improve the soil permeability, aerobic condition and methanogenic activities, which may enhance the inhibition effect of NT on the CH4 and N2O emissions [28, 71]. NT significantly increased the N2O emission under the double rice system. This was possibly because of the difference in temperature between late rice and winter upland crops. Late rice was commonly planted in summer, whereas winter upland crops were planted in fall. Higher temperature with surface applied N fertilizer may stimulate the N2O emission [57]. RT significantly increased the CH4 emission and the overall GWP under the double rice system. But it should be noted that only three comparisons from two studies were included for this category. The existence of publication bias was suggested by Spearman Rank-Order Correlation.

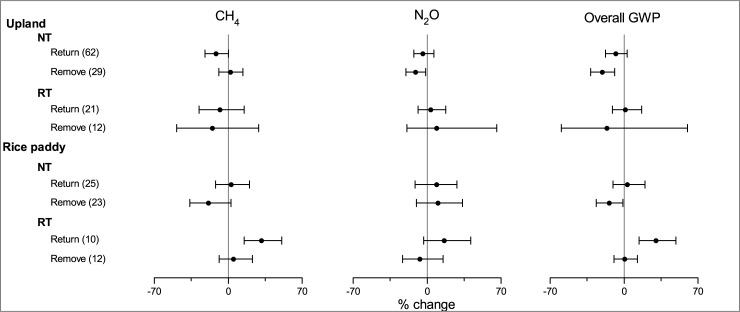

Impact of crop straw management

NT significantly reduced the N2O emission and the overall GWP by 10.9% and 20.4% as compared with CT, respectively, when crop straw was removed (Fig 5). However, when the crop straw was returned, the effect sizes of NT on CH4 uptake, N2O emission, and overall GWP were not significant. Crop straw has direct and indirect positive effects on N2O production. The decomposition of crop straw directly provided substrate C and N for nitrifiers and denitrifiers, which may stimulate the N2O production in soil [68]. Indirectly, the returned crop straw was commonly mulched on the soil surface in the NT field, which could reduce soil water evaporation and conserve rainwater in situ, resulting in enhanced soil moisture [72]. High soil moisture promotes N2O production and inhibits CH4 oxidation by reducing gas diffusion [73–74]. Therefore, crop straw return may weaken the effects of NT on the mitigation of N2O and CH4 emissions.

Fig 5. Impact of crop straw management on the effects of NT and RT on CH4, N2O and overall GWP.

As in paddy fields, NT significantly reduced the overall GWP by 20.4% when crop straw was removed; but did not affect the overall GWP when crop straw was returned (Fig 5). RT significantly increased the CH4 emission and overall GWP when crop straw was returned; whereas it did not increase the overall GWP when crop straw was removed. The effect of soil tillage on CH4 emission in paddy field was mostly determined by its influence on straw decomposition, which provides abundant C substrate for CH4 production [75]. Soil tillage determined the vertical distribution of crop straw in the soil profile. RT usually mixed straw into the surface soil (5–10cm depth); whereas plowing in CT buried the crop straw into the deeper soil layer (10–15cm), which could reduce access of these residues by microbes by the protection of soil matrix [28]. Thus, RT with crop straw return might facilitate crop straw decomposition into intermediate products that serves as substrates for methanogens [67], resulting in producing higher CH4.

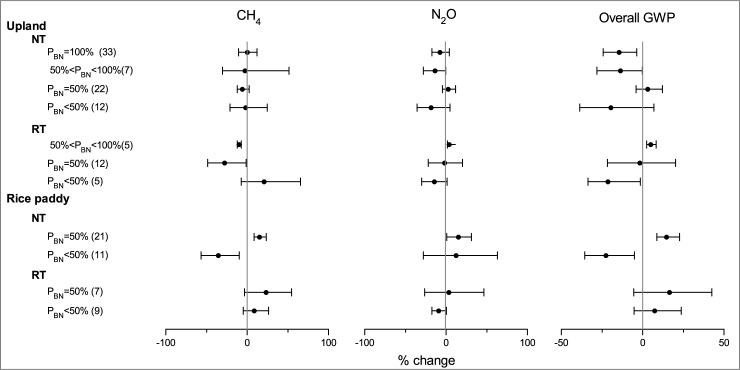

Impact of N split

Split application of N fertilizer is an important practice to synchronize nutrient supply with crop demand and reduce N loss to the environment. Tillage directly affected the vertical distribution and transformation of basal N fertilizer. The effectiveness of NT/RT on CH4 and N2O emissions may influenced by the percentage of basal N fertilizer (PBN). As shown in Fig 6, when the PBN = 100%, NT significantly reduced the overall GWP by 14.4% in upland, as compared with CT. When 50% < PBN < 100%, the overall GWP was marginally significantly mitigated by 13.6% by NT in upland. When PBN < or = 50%, NT did not significantly affect CH4 uptake, N2O emission, and the overall GWP. This can be explained by two possible reasons. Firstly, basal N fertilizer is commonly applied with tillage operation; whereas topdressing N fertilizer is usually applied with irrigation or precipitation in uplands. Soil tillage had a greater effect on the microbial process of the basal N fertilizer than top dressing N fertilizer. Thus, high PBN may intensify the inhibition effect of NT on N2O emission. Secondly, a large amount of field studies has reported that reducing the ratio of basal N and increasing the ratio of topdressing N enhanced plant N recovery and the N use efficiency [76]. Less PBN could improve the synchronization of crop demand with N supply and inhibit N2O emission. Therefore, the better synchronization of crop demand with N supply may weaken the inhibition effect of NT on N2O emission. RT significantly reduced CH4 oxidation and enhanced N2O emission when the percentage of PBN was between 50% and 100% in uplands (Fig 6). The overall GWP was significantly enhanced by 5.1% by RT. However, the existence of publication bias was suggested by Spearman Rank-Order Correlation. When PBN was decreased to less than 50%, RT significantly mitigated the overall GWP because of the increase in CH4 uptake and the reduction in N2O emission. These results indicated that high PBN (> 50%) with NT and low PBN (< 50%) with RT benefited the GHG mitigation in upland fields.

Fig 6. Impact of N split application on the effects of NT and RT on CH4, N2O and overall GWP.

As in paddy fields, NT significantly mitigated the overall GWP by 22.4% when PBN < 50%; whereas increased the overall GWP by 14.9% when PBN = 50%, which was different from that of uplands (Fig 6). The effectiveness of NT on overall GWP was largely determined by its impact on CH4 emission in paddy fields. The surface application of basal N fertilizer under NT could have either positive or negative effects on CH4 emission. On one hand, the production of CH4 mostly occurred at the surface layer because of the surface application of basal N fertilizer under NT, which benefited the diffusion of CH4 from the soil to the atmosphere [21]. On the other hand, a shallow CH4 production zone may also benefit CH4 oxidation, because the interface between water and soil was a main CH4 oxidation zone [37]. The integrated effect was possibly determined by the basal N application rate. The average basal N rate were 45 and 90 kg N ha-1 for the groups of PBN < 50% and PBN = 50%, respectively. We speculated that, at low PBN, rice uptake might outcompete the microbial process of CH4 production because of the limited N source [77]; and the capability of CH4 oxidation was possibly higher than CH4 production because of the insufficiency available N for Methanogenic bacteria. Thus, NT inhibited CH4 emission. With the PBN increased to 50%, the N supply for Methanogenic bacteria was less serve, and the abundant N supply stimulated CH4 production and inhibited CH4 oxidation by suppressing Methanotrophs and switching substrates from CH4 to ammonia [78–79]. Additionally, the shallow CH4 production zone under NT may enhance the flux of CH4 from soil to atmosphere. Thus, NT significantly increased the CH4 emission under high basal N application rates.

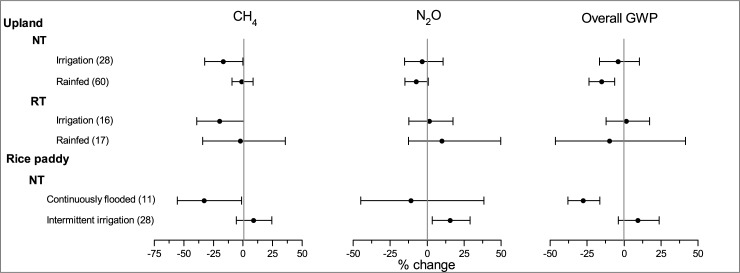

Impact of irrigation

As shown in Fig 7, NT significantly reduced the overall GWP by 16.7% under rain-fed condition as compared with CT. The effect of NT on the overall GWP was not significant under irrigation option. NT improved soil structure, which increased the gas diffusivity and improved the tendency of the formation of aerobic microsites, and therefore increased CH4 oxidation and inhibited N2O emission [80–81]. The irrigation options in selected studies were all flooding irrigation, which may weaken the effectiveness of NT by increasing soil water and decreasing the aerobic condition in soil profile [13].

Fig 7. Impact of irrigation on the effects of NT and RT on CH4, N2O and overall GWP.

As in paddy fields, NT significantly mitigated CH4 emission and overall GWP in continuously flooded paddy field as compared with CT (Fig 7); whereas it did not produce a significant effect on CH4 and overall GWP in intermittently irrigated paddy fields as compared with CT. Continuous flooding provided a sufficient anaerobic environment for CH4 production in paddy fields. Thus, the labile C availability and CH4 oxidation capacity were two important factors controlling the total CH4 emission amount in flooded paddies. A previous field study showed that NT reduced the volume fraction of large soil pores, which was conducive to the prevention of the decomposition of soil organic matter [12]. Additionally, most of the crop residue and inorganic N fertilizer were placed on the soil surface in NT paddy fields, which enhanced the CH4 oxidation and prevented the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter because of the high O2 content in the soil-water interface [6, 37]. Therefore, NT was conducive to inhibition of CH4 emission under continuous flooded field conditions. As in intermittent irrigated field, the water usually drained out and maintained the dry-wet alternation after the rice tillering stage, which greatly increased the aerobic periods and mitigated the CH4 emission as compared with that of continuous flooding [82]. Thus, intermittent irrigation may weaken the effect of NT on the inhibition of CH4 emission.

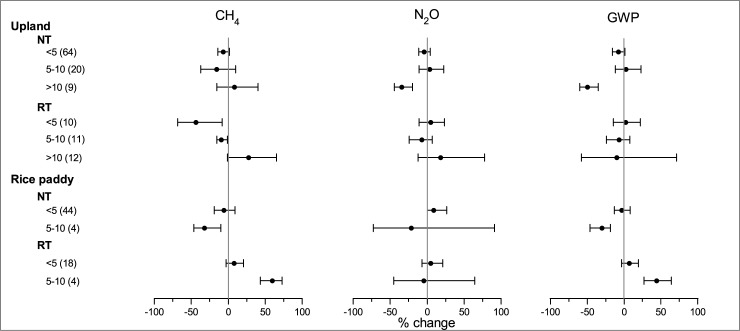

Impact of tillage duration

NT only significantly mitigated N2O emission and overall GWP under long-term duration (>10 years) in uplands (Fig 8), which is consistent with previous studies [14, 83]. Long-term adoption of NT can improve soil structure and therefore is conducive to the enhancement of CH4 uptake and inhibition of N2O emission [81]. The inhibition effect of RT on overall GWP showed a trend that increase with tillage duration. However, its effectiveness was not significant because of wide variance.

Fig 8. Impact of tillage duration on the effects of NT and RT on CH4, N2O and overall GWP.

As in paddy field, NT did not exhibit significant effects on CH4 and overall GWP under short-term duration (<5 years); whereas it significantly reduced CH4 and overall GWP under medium-term duration (5–10 years) (Fig 8). The existence of publication bias for the category of 5–10 years was suggested by Spearman Rank-Order Correlation. Based on a five-year field experiment, Kim et al. [22] reported that NT effectively reduced the CH4 emission in the 1st and 2nd years, but increased the CH4 emission in the 5th year, because of increased soil organic carbon (SOC) content, as compared with CT. The contrasting results were possibly attributed to the difference in the cropping practices. The cropping system in the study of Kim et al. [22] was mono-rice with winter fallow; and the crop residue was placed in the field after rice harvest and would have completely decomposed under aerobic conditions in winter [84–85]. The SOC content was possibly the primary factor determining the CH4 production in the following rice cropping season. Thus, NT increased the SOC resulting in enhanced CH4 emission. As in the selected studies [86–87] in this analysis, the cropping systems were rice-upland crops rotation and the upland crop residue applied preceding the rice cropping provided an abundant substrate for CH4 production. The effect of NT on CH4 emission was possibly controlled by its impact on CH4 oxidation. Thus, continuous adoption of NT may facilitate the CH4 oxidation and significantly reduce the CH4 emission. These results indicated that the temporal effect of NT in rice paddies might highly depend on the cropping system. However, the long-term experiment of NT in paddy fields was still limited. The number of long-term experiments conducted in paddy field was far less than that in upland. More field studies are needed to investigate the temporal effect of NT on GHG emission in paddy field under different agricultural practices.

Summary

NT/RT significantly reduced the overall GWP of CH4 and N2O emissions by 6.6% as compared with CT. The effectiveness of NT/RT depended on tillage methods, land use type, and agricultural practices. The suggested practices for NT to reduce the GHG emission were crop rotation and straw remove both in upland and paddy field, PBN>50% and rainfed in upland, while PBN<50% in paddy field. RT was less effective on the mitigation of GHG emission than NT. RT significantly enhanced the CH4, N2O or overall GWP under several practices, such as double rice system and crop straw returned in paddy field, and PBN>50% in upland. Only single crop monoculture facilitated RT to reduce the overall GWP.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the State Key Program of China (2016YFD0300906 to JF) and the Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

References

- 1.US-EPA, 2012. Global Anthropogenic Non-CO 2 Greenhouse Gas Emissions: 1990–2030. Washington, U.S. https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/Downloads/EPAactivities/EPA_Global_NonCO2_Projections_Dec2012.pdf.

- 2.Smith P., Bustamante M, Ahammad H., Clark H., Dong H., Elsiddig E. A., et al. 2014. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU) In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer O., Pichs-Madruga R., Sokona Y., Farahani E., Kadner S, Seyboth K., Adler A., Baum I., Brunner S., Eickemeier P., Kriemann B., Savolainen J., Schlömer S., von Stechow C., Zwickel T. and Minx J.C. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdalla K., Chivenge P., Ciais P., Chaplot V., 2016. No-tillage lessens soil CO2 emissions the most under arid and sandy soil conditions: results from a meta-analysis. Biogeosciences 13, 3619–3633. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neufeldt H., Kissinger G., Alcamo J., 2015. No-till agriculture and climate change mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 488–489. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powlson D.S., Stirling C.M., Jat M., Gerard B.G., Palm C.A., Sanchez P.A., et al. , 2014. Limited potential of no-till agriculture for climate change mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 678–683. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harada H., Kobayashi H., Shindo H., 2007. Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by no-tilling rice cultivation in Hachirogata polder, northern Japan: Life-cycle inventory analysis. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 53, 668–677. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L., Zheng J., Chen L., Shen M., Zhang X., Zhang M., et al. , 2015. Integrative effects of soil tillage and straw management on crop yields and greenhouse gas emissions in a rice-wheat cropping system. Eur. J. Agron. 63, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayer C., Zschornack T., Pedroso G.M., da Rosa C.M., Camargo E.S., Boeni M., et al. , 2015. A seven-year study on the effects of fall soil tillage on yield-scaled greenhouse gas emission from flood irrigated rice in a humid subtropical climate. Soil Till. Res. 145, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tellez-Rio A., Garcia-Marco S., Navas M., Lopez-Solanilla E., Tenorio J.L., Vallejo A., 2015. N2O and CH4 emissions from a fallow-wheat rotation with low N input in conservation and conventional tillage under a Mediterranean agroecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 508, 85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith D.R., Hernandez-Ramirez G., Armstrong S.D., Bucholtz D.L., Stott D.E., 2011. Fertilizer and Tillage Management Impacts on Non-Carbon-Dioxide Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 75, 1070–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sainju U.M., Stevens W.B., Caesar-TonThat T., Liebig M.A., Wang J., 2014. Net Global Warming Potential and Greenhouse Gas Intensity Influenced by Irrigation, Tillage, Crop Rotation, and Nitrogen Fertilization. J. Environ. Qual. 43, 777–788. doi: 10.2134/jeq2013.10.0405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad S., Li C., Dai G., Zhan M., Wang J., Pan S., et al. , 2009. Greenhouse gas emission from direct seeding paddy field under different rice tillage systems in central China. Soil Till. Res. 106, 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sainju U.M., Stevens W.B., Caesar-TonThat T., Liebig M.A., 2012. Soil Greenhouse Gas Emissions Affected by Irrigation, Tillage, Crop Rotation, and Nitrogen Fertilization. J. Environ. Qual. 41, 1774–1786. doi: 10.2134/jeq2012.0176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Kessel C., Venterea R., Six J., Adviento-Borbe M.A., Linquist B., van Groenigen K.J., 2013. Climate, duration, and N placement determine N2O emissions in reduced tillage systems: a meta-analysis. Global Change Biol. 19, 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao X., Liu S.L., Pu C., Zhang X.Q., Xue J.F., Zhang R., et al. , 2016. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions under no-till farming in China: a meta-analysis. Global Change Biol. 22, 1372–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessavalou A., Mosier A.R., Doran J.W., Drijber R.A., Lyon D.J., Heinemeyer O., 1998. Fluxes of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, and methane in grass sod and winter wheat-fallow tillage management. J. Environ. Qual. 27, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangalassery S., Sjoegersten S., Sparkes D.L., Sturrock C.J., Craigon J., Mooney S.J., 2014. To what extent can zero tillage lead to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from temperate soils? Sci. Rep.-UK 4:4586 doi: 10.1038/srep04586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamulki S., Jarvis S.C., 2002. Short-term effects of tillage and compaction on nitrous oxide, nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, methane and carbon dioxide fluxes from grassland. Biol. Fert. Soils 36, 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubbers I.M., van Groenigen K.J., Brussaard L., van Groenigen J.W., 2015. Reduced greenhouse gas mitigation potential of no-tillage soils through earthworm activity. Sci. Rep.-UK 5:13787 doi: 10.1038/srep13787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li D., Liu M., Cheng Y., Wang D., Qin J., Jiao J., et al. , 2011. Methane emissions from double-rice cropping system under conventional and no tillage in southeast China. Soil Till. Res. 113, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M., Li J., Zhen X., 1998. Methane emission and mechanisms of methane production, oxidation and transportation in the rice fields. Sci. Atmos. Sin. 22, 600–612. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S.Y., Gutierrez J., Kim P.J., 2016. Unexpected stimulation of CH4 emissions under continuous no-tillage system in mono-rice paddy soils during cultivation. Geoderma 267, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao Q., Jiang C., Chai X., Huang Z., Fan Z., Xie D., et al. , 2016. Drainage, no-tillage and crop rotation decreases annual cumulative emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from a rice field in Southwest China. Agr. Ecosys. Environ. 233, 270–281. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosier A.R., Delgado J.A., Keller M., 1998. Methane and nitrous oxide fluxes in an acid Oxisol in western Puerto Rico: Effects of tillage, liming and fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30, 2087–2098. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C., Zhang R., Zhang J., Cai L., Zhou H., Dong B., 2015. N2O and CH4 emissions of spring wheat-pea rotation fields under different tillage patterns in dryland farming in a wet year. Agr. Res. Arid Area. 33, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng C., Zeng Y., Yang X., Huang S., Luo K., Shi Q., et al. , 2015. Effect of different tillage methods on net global warming potential and greenhouse gas intensity in double rice-cropping systems. Acta Scien. Cirum. 35, 1887–1895. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Z.S., Guo L.J., Liu T.Q., Li C.F., Cao C.G., 2015. Effects of tillage practices and straw returning methods on greenhouse gas emissions and net ecosystem economic budget in rice wheat cropping systems in central China. Atmos. Environ. 122, 636–644. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y., Sheng J., Wang Z., Chen L., Zheng J., 2015. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from a Chinese wheat-rice cropping system under different tillage practices during the wheat-growing season. Soil Till. Res. 146, 261–269. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latifmanesh H., 2015. Effects of soil tillage on crop yield and greenhouse gas emission of corn-wheat cropping system. Chiese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qin X., Li Y.e., Wan Y., Liao Y., Fan M., Gao Q., et al. , 2014. Effect of tillage and rice residue return on CH4 and N2O emission from double rice field. Trans. Chinese Soc. Agr. Eng. 30, 216–224. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang B., Yang S., Ma Y., He F., Zuo H., Fan D., et al. , 2014. Effects on emission of greenhouse gas by different tillage treatments to winter wheat in polder areas. J. Anhui Agr. Univ. 41, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yonemura S., Nouchi I., Nishimura S., Sakurai G., Togami K., Yagi K., 2014. Soil respiration, N2O, and CH4 emissions from an Andisol under conventional-tillage and no-tillage cultivation for 4 years. Biol. Fert. Soils 50, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sander B.O., Samson M., Buresh R.J., 2014. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from flooded rice fields as affected by water and straw management between rice crops. Geoderma 235, 355–362. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bayer C., Costa F.d.S., Pedroso G.M., Zschornack T., Camargo E.S., de Lima M.A., et al. , 2014. Yield-scaled greenhouse gas emissions from flood irrigated rice under long-term conventional tillage and no-till systems in a Humid Subtropical climate. Field Crop. Res. 162, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang B., 2013. The rules and regulation of farmland carbon cycle under conservational tillage Shandong Agricultural University. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai L., Wang J., Luo Z., Wu J., Zhang R., 2013. Greenhouse gas emissions in double sequence pea-wheat rotation fields under different tillage conditions. Chinese J. Eco-agr. 21, 921–930. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H.L., Bai X.L., Xue J.F., Chen Z.D., Tang H.M., Chen F., 2013. Emissions of CH4 and N2O under Different Tillage Systems from Double-Cropped Paddy Fields in Southern China. Plos One 8, e65277 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao Z., Zheng X., Wang R., Xie B., Butterbach-Bahl K., Zhu J., 2013. Nitrous oxide and methane fluxes from a rice-wheat crop rotation under wheat residue incorporation and no-tillage practices. Atmos. Environ. 79, 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian S., Wang Y., Ning T., Zhao H., Wang B., Li N., et al. , 2013. Greenhouse Gas Flux and Crop Productivity after 10 Years of Reduced and No Tillage in a Wheat-Maize Cropping System. Plos One 8, e73450 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J., Jiang C., Hao Q., Tang Q., Cheng B., Li H., et al. , 2012. Effect of tillage cropping system on methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agro-ecosystems in a purple paddy soils. Environ. Sci. 33, 1979–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian S., Ning T., Zhao H., Wang B., Li N., Han H., et al. , 2012. Response of CH4 and N2O Emissions and Wheat Yields to Tillage Method Changes in the North China Plain. Plos One 7, e51206 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dendooven L., Gutierrez-Oliva V.F., Patino-Zuniga L., Ramirez-Villanueva D.A., Verhulst N., Luna-Guido M., et al. , 2012. Greenhouse gas emissions under conservation agriculture compared to traditional cultivation of maize in the central highlands of Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 431, 237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z., Liu J., Yu Q., Wang R., Wang Y., Cui F., 2011. Effect of oat tillage systems on greenhouse gas emissions in dry land. Agr. Res. Arid Area. 29, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang J., Cai L., Zhang R., Wang Y., Dong W., 2011. Effect of tillage pattern on soil greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4 and N2O) fluxes in semi-arid termperate region. Chinese J. Eco-agr. 19, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y., Zheng J., Chen L., Wang Z., Zhu P., Shen J., et al. , 2009. Effect of wheat straw returning and soil tillage on CH4 and N2O emissions in paddy season. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 18, 2334–2338. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metay A., Oliver R., Scopel E., Douzet J.M., Alves Moreira J.A., Maraux F., et al. , 2007. N2O and CH4 emissions from soils under conventional and no-till management practices in Goiania (Cerrados, Brazil). Geoderma 141, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu X.J., Mosier A.R., Halvorson A.D., Zhang F.S., 2006. The impact of nitrogen placement and tillage on NO, N2O, CH4 and CO2 fluxes from a clay loam soil. Plant Soil 280, 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koga N., Tsuruta H., Sawamoto T., Nishimura S., Yagi K., 2004. N2O emission and CH4 uptake in arable fields managed under conventional and reduced tillage cropping systems in northern Japan. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 18. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kessavalou A., Doran J.W., Mosier A.R., Drijber R.A., 1998. Greenhouse gas fluxes following tillage and wetting in a wheat-fallow cropping system. J. Environ. Qual. 27, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guardia G., Tellez-Rio A., Garcia-Marco S., Martin-Lammerding D., Tenorio J.L., Ibanez M.A., et al. , 2016. Effect of tillage and crop (cereal versus legume) on greenhouse gas emissions and Global Warming Potential in a non-irrigated Mediterranean field. Agr. Ecosys. Environ. 221, 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y., Hu C., Wang Y., Dong W., Qin S., Li X., 2016. Greenhouse gases exchange and their comprehensive global warming potentials in different tillage wheat-maize rotation field. Chinese J. Eco-agr. 24, 704–715. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X., Zhou W., Wang Z., Sheng J., Chen L., Zheng J., et al. , 2016. Effect of soil tillage and straw return on wheat yield and greenhouse gases emission. J. Yangzhou Univ. 37, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Z.S., Chen J., Liu T.Q., Cao C.G., Li C.F., 2016. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer sources and tillage practices on greenhouse gas emissions in paddy fields of central China. Atmos. Environ. 144, 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yeboah S., Zhang R., Cai L., Song M., Li L., Xie J., et al. , 2016. Greenhouse gas emissions in a spring wheat-field pea sequence under different tillage practices in semi-arid Northwest China. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 106, 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garcia-Marco S., Abalos D., Espejo R., Vallejo A., Mariscal-Sancho I., 2016. No tillage and liming reduce greenhouse gas emissions from poorly drained agricultural soils in Mediterranean regions. Sci. Total Environ. 566, 512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.05.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fangueiro D., Becerra D., Albarran A., Pena D., Sanchez-Llerena J., Rato-Nunes J.M., et al. , 2017. Effect of tillage and water management on GHG emissions from Mediterranean rice growing ecosystems. Atmos. Environ. 150, 303–312. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang G., Yu H., Fan X., Yang Y., Ma J., Xu H., 2016a. Drainage and tillage practices in the winter fallow season mitigate CH4 and N2O emissions from a double-rice field in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 11853–11866. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta D.K., Bhatia A., Kumar A., Das T.K., Jain N., Tomer R., et al. , 2016. Mitigation of greenhouse gas emission from rice-wheat system of the Indo-Gangetic plains: Through tillage, irrigation and fertilizer management. Agr. Ecosys. Environ. 230, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toma Y., Oomori S., Maruyama A., Ueno H., Nagata O., 2016. Effect of the number of tillages in fallow season and fertilizer type on greenhouse gas emission from a rice (Oryza sativa L.) paddy field in Ehime, southwestern Japan. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 62, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yagioka A., Komatsuzaki M., Kaneko N., Ueno H., 2015. Effect of no-tillage with weed cover mulching versus conventional tillage on global warming potential and nitrate leaching. Agr. Ecosys. Environ. 200, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tellez-Rio A., Garcia-Marco S., Navas M., Lopez-Solanilla E., Rees R.M., Luis Tenorio J., et al. , 2015. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from a vetch cropping season are changed by long-term tillage practices in a Mediterranean agroecosystem. Biol. Fert. Soils 51, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu S., Zhao C., Zhang Y., Hu Z., Wang C., Zong Y., et al. , 2015. Annual net greenhouse gas balance in a halophyte (Helianthus tuberosus) bioenergy cropping system under various soil practices in Southeast China. GCB Bioenergy 7, 690–703. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duan C., 2013. Effect of Conservation tillage on greenhouse gases flux from farmland soil in dry land of the Loess Plateau Gansu Agriculture University. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang J, Jiang C, Hao Q, Tang Q, Cheng B, Li H, et al. , 2012. Effect of tillage cropping system on methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agro-ecosystems in a purple paddy soils. Environ. Sci. 33, 1979–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rosenberg, M.S., Adams, D.C., Gurevitch, J., 2000. METAWIN, Statistical software for meta-analysis, Version 2. Sinauer, Sunderland, MA.

- 66.Linquist B., van Groenigen K.J., Adviento-Borbe M.A., Pittelkow C., van Kessel C., 2012. An agronomic assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from major cereal crops. Global Change Biol. 18, 194–209. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Le Mer J., Roger P., 2001. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: A review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 37, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen H., Li X., Hu F., Shi W., 2013. Soil nitrous oxide emissions following crop residue addition: a meta-analysis. Global change biol. 19, 2956–2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hutsch B.W., 2001. Methane oxidation in non-flooded soils as affected by crop production. Eur. J. Agron. 14, 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu H., Cai Z.C., Tsuruta H., 2003. Soil moisture between rice-growing seasons affects methane emission, production, and oxidation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 67, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feng J., Chen C., Zhang Y., Song Z., Deng A., Zheng C., et al. , 2013. Impacts of cropping practices on yield-scaled greenhouse gas emissions from rice fields in China: A meta-analysis. Agr. Ecosys. Environ. 164, 220–228. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharma P.K., Acharya C.L., 2000. Carry-over of residual soil moisture with mulching and conservation tillage practices for sowing of rainfed wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) in north-west India. Soil Till. Res. 57, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boeckx P., Van Cleemput O., 1996. Methane Oxidation in a Neutral Landfill Cover Soil: Influence of Moisture Content, Temperature, and Nitrogen-Turnover. J. Environ. Qual. 25, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maag M., Vinther F.P., 1996. Nitrous oxide emission by nitrification and denitrification in different soil types and at different soil moisture contents and temperatures. Appl. Soil Ecol. 4, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ma J., Ma E., Xu H., Yagi K., Cai Z., 2009. Wheat straw management affects CH4 and N2O emissions from rice fields. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang S.J., Luo S.S., Yue S.C., Shen Y.F., Li S.Q., 2016. Fate of N-15 fertilizer under different nitrogen split applications to plastic mulched maize in semiarid farmland. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 105, 129–140. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cai Z., Shan Y., Xu H., 2007. Effects of nitrogen fertilization on CH4 emissions from rice fields. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 53, 353–361. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dubey S.K., 2003. Spatio-kinetic variation of methane oxidizing bacteria in paddy soil at mid-tillering: effect of N-fertilizers. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosys. 65, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hanson R.S., Hanson T.E., 1996. Methanotrophic bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 60, 439–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malhi S.S., Lemke R., Wang Z.H., Chhabra B.S., 2006. Tillage, nitrogen and crop residue effects on crop yield, nutrient uptake, soil quality, and greenhouse gas emissions. Soil Till. Res. 90, 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ussiri D.A.N., Lal R., Jarecki M.K., 2009. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from long-term tillage under a continuous corn cropping system in Ohio. Soil Till. Res. 104, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zou J., Huang Y., Jiang J., Zheng X., Sass R.L., 2005. A 3-year field measurement of methane and nitrous oxide emissions from rice paddies in China: Effects of water regime, crop residue, and fertilizer application. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 19, GB2021. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Six J., Ogle S.M., Breidt F.J., Conant R.T., Mosier A.R., Paustian K., 2004. The potential to mitigate global warming with no-tillage management is only realized when practised in the long term. Global Change Biol. 10, 155–160. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu H., Cai Z.C., Li X.P., Tsuruta H., 2000. Effect of antecedent soil water regime and rice straw application time on CH4 emission from rice cultivation. Aust. J. Soil Res. 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yan X., Akiyama H., Yagi K., Akimoto H., 2009. Global estimations of the inventory and mitigation potential of methane emissions from rice cultivation conducted using the 2006 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Guidelines. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 23, GB2002. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bayer C., Gomes J., Zanatta J.A., Vieira F.C.B., Dieckow J., 2016. Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from a subtropical Ultisol by using long-term no-tillage in combination with legume cover crops. Soil Till. Res. 161, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Metay A., Oliver R., Scopel E., Douzet J.M., Alves Moreira J.A., Maraux F., et al. , 2007. N2O and CH4 emissions from soils under conventional and no-till management practices in Goiania (Cerrados, Brazil). Geoderma 141, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

(DOCX)

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.