Abstract

Background: The Institute of Medicine (IOM) revised gestational weight gain recommendations in 2009. We examined associations between healthcare provider advice about gestational weight gain and inadequate or excessive weight gain, stratified by prepregnancy body mass index category.

Materials and Methods: We analyzed cross-sectional data from women delivering full-term (37–42 weeks of gestation), singleton infants from four states that participated in the 2010–2011 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (unweighted n = 7125). Women reported the weight gain range (start and end values) advised by their healthcare provider; advice was categorized as follows: starting below recommendations, starting and ending within recommendations (IOM consistent), ending above recommendations, not remembered, or not received. We examined associations between healthcare provider advice and inadequate or excessive, compared with appropriate, gestational weight gain using adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: Overall, 26.3% of women reported receiving IOM-consistent healthcare provider advice; 26.0% received no advice. Compared with IOM-consistent advice, advice below recommendations was associated with higher likelihood of inadequate weight gain among underweight (aPR 2.22, CI 1.29–3.82) and normal weight women (aPR 1.57, CI 1.23–2.02); advice above recommendations was associated with higher likelihood of excessive weight gain among all but underweight women (aPR range 1.36, CI 1.08–1.72 to aPR 1.42, CI 1.19–1.71). Not remembering or not receiving advice was associated with both inadequate and excessive weight gain.

Conclusions: Few women reported receiving IOM-consistent advice; not receiving IOM-consistent advice put women at-risk for weight gain outside recommendations. Strategies that raise awareness of IOM recommendations and address barriers to providing advice are needed.

Keywords: : PRAMS, gestational weight gain, counseling, pregnancy, healthcare providers

Introduction

Recent studies indicate that less than one-third of women had gestational weight gain within the 2009 Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommendations, whereas one-fifth gained below and nearly half gained above recommendations.1,2 The IOM recommendations, which are specific to a woman's prepregnancy body mass index (BMI; weight [kg]/height [m]2), balance risks associated with too little weight gain and risks associated with too much weight gain to promote optimal maternal and infant health.3 Weight gain below recommendations is associated with small-for-gestational age infants, whereas weight gain above recommendations is associated with large-for-gestational age infants, cesarean delivery, possibly childhood obesity, and maternal postpartum weight retention, which may contribute to the development or worsening of obesity.3–5

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends healthcare providers calculate prepregnancy BMI at the initial prenatal care visit and discuss gestational weight gain in accordance with IOM recommendations.6 Despite this guidance, studies indicate 28%–81% of women report receiving any advice from a healthcare provider about gestational weight gain7–16 and 12%–49% report receiving advice consistent with IOM recommendations.7,9,10,12–16 Healthcare provider advice about gestational weight gain has also been found to influence weight gain during pregnancy.7,9 These earlier studies examined previous IOM recommendations,7,9,10,12 which lacked a defined upper limit for women with obesity, or used data from small, Internet- or clinic-based samples,13–16 limiting generalizability to broader populations.

Our objective was to estimate the proportion of women receiving healthcare provider advice about gestational weight gain consistent with 2009 IOM recommendations using representative, population-based data. We also assessed the relationship between healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain, stratified by prepregnancy BMI category.

Materials and Methods

Study sample

Data are from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), a cross-sectional surveillance system administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state governments.17 Each month, participating states systematically sample 100–250 mothers ∼4 months postpartum using birth records as a sampling frame. Sampled mothers are mailed a questionnaire, and those not responding after multiple mailed follow-up attempts are contacted by telephone to complete the questionnaire via interview.

The PRAMS questionnaire assesses maternal characteristics and pregnancy-related behaviors and experiences (e.g., contraceptive use and content of prenatal care) and data are linked to select demographic and medical information from the birth certificate (e.g., maternal age and gestational weight gain). Data are weighted to account for survey design, noncoverage, and nonresponse to provide representative estimates of the female population delivering a live birth in each state. The PRAMS protocol has been reviewed and approved by the CDC Institutional Review Board. States included in this analysis approved the analysis plan and met the 65% response rate threshold.

We used Phase 6 (2009–2011) data from Colorado, Georgia, Maine, and Utah because these states included optional questions on the PRAMS questionnaire that assessed healthcare provider advice about gestational weight gain. Healthcare provider advice was also assessed on the Phase 7 questionnaire for Colorado and Utah; however, we chose not to analyze these data because gestational weight gain was also self-reported on the Phase 7 questionnaire (but not on Phase 6), which may influence women's report of healthcare provider advice. Because the IOM gestational weight gain recommendations were revised in 2009, we examined only 2010–2011 data.

Women were eligible for this analysis if they delivered a full-term (37–42 weeks of gestation), singleton infant (n = 8600). We excluded women with missing gestational weight gain (n = 527), missing or implausible prepregnancy weight (less than 75 pounds or more than 450 pounds; n = 194), missing or implausible height (less than 48 inches or more than 78 inches; n = 238), or missing healthcare provider advice (n = 119). Women with advice starting below and ending above the IOM recommendation, as described under Measures section, were excluded due to insufficient sample sizes (n = 94). In addition, we excluded women with missing covariate data (n = 303). Our final sample size was 83% of our eligible population (unweighted n = 7125), which represents ∼80% of births in Colorado, Georgia, Maine, and Utah in 2010–2011.

Measures

Our outcome of interest was gestational weight gain below, within, or above women's BMI-specific 2009 IOM recommendation (referred to as inadequate, appropriate, or excessive, respectively). The 2009 IOM recommendations are as follows: 28–40 pounds for underweight (BMI <18.5), 25–35 pounds for normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), 15–25 pounds for overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9), and 11–20 pounds for obese women (BMI ≥30.0).3 Total gestational weight gain was obtained from the birth certificate. Prepregnancy BMI was calculated using self-reported height and prepregnancy weight from the PRAMS questionnaire.

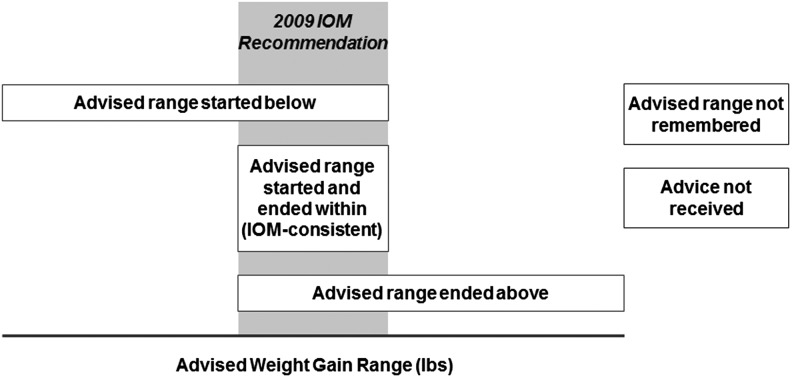

Our exposure of interest was women's report of healthcare provider advice about gestational weight gain. On the PRAMS questionnaire, women were asked whether any healthcare provider (i.e., a doctor, nurse, or other healthcare provider) discussed how much weight to gain during pregnancy. Women who indicated receiving advice from a healthcare provider were prompted to report the advised amount of weight gain (recorded as start and end values of a range or an exact amount), or to indicate advice was not remembered. We used the start and end values (or exact amount) of the advised weight gain range to create two variables describing healthcare provider advice relative to women's BMI-specific IOM gestational weight gain recommendation. The first variable was used in stratified analyses to ensure model stability and had five levels (Fig. 1): advised weight gain range started below the recommendation; advised weight gain range started and ended within the recommendation (referred to as IOM consistent); advised weight gain range ended above the recommendation; advised weight gain range was not remembered or not indicated; and no weight gain advice was received.

FIG. 1.

Categorization scheme for healthcare provider advice relative to 2009 IOM recommendations. The gray bar represents a woman's IOM gestational weight gain recommendation. The white bar represents the advised weight gain range from a healthcare provider and corresponding category created for the healthcare provider advice variable. Women were categorized if their advised weight gain range started below the recommendation; advised weight gain range started and ended within the recommendation (referred to as IOM consistent); advised weight gain range ended above the recommendation; advised weight gain range was not remembered or not indicated; or no weight gain advice was received. Women with an advised weight gain range starting below and ending above recommendations were excluded due to small sample sizes. IOM, Institute of Medicine.

The second variable describing healthcare provider advice was used to explore the dose/response relationship between healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain, and expanded the five-level exposure variable to seven levels. The expanded variable distinguished advice that started and ended below recommendations from advice that started below but ended within recommendations, and distinguished advice that started within and ended above recommendations from advice that started and ended above recommendations (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/jwh). The levels are as follows: advised weight gain range started and ended below the recommendations; advised weight gain range started below and ended within the recommendations; advised weight gain range started and ended within the recommendation (i.e., IOM consistent); advised weight gain range started within and ended above the recommendation; advised weight gain range started above and ended above the recommendation; advised weight gain range was not remembered or not indicated; and no weight gain advice received.

Women with an advised weight gain range that started below and ended above recommendations were excluded from both exposure variables due to insufficient sample sizes (n = 94). Because we observed terminal digit preference18 in women's report of advised weight gain (i.e., “0” or “5” was the most frequently reported terminal digit for advised weight gain values, regardless of prepregnancy BMI category), we considered an advised weight gain range of 25–40 pounds for underweight women and 10–20 pounds for obese women to be consistent with the IOM recommendations.

Covariates included maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, parity, and marital status, which were obtained from the birth certificate, and first trimester entrance into prenatal care, which was obtained from the PRAMS questionnaire. Information for the following additional variables was based on positive indication on either the birth certificate or questionnaire: enrollment in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); smoking status (defined as nonsmokers [no smoking before or during pregnancy], quitters [smoking before pregnancy, but not in the third trimester], or smokers [smoking in the third trimester]); hypertensive conditions (i.e., prepregnancy hypertension, gestational hypertension, or pre-eclampsia); and diabetic conditions (i.e., chronic or gestational diabetes).

Statistical analysis

We used Wald chi-square tests to identify significant differences in proportions of women receiving healthcare provider advice by maternal characteristics. To examine the association between healthcare provider advice and inadequate or excessive, compared with appropriate, gestational weight gain, we estimated unadjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) and confidence intervals (95% CIs) using predicted marginal proportions from multinomial logistic regression models19; we also estimated PRs adjusted for all covariates previously mentioned, which were identified as confounders a priori using causal diagrams.

We examined the association between healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain stratified by prepregnancy BMI category because gestational weight gain recommendations are specific to a woman's prepregnancy BMI3; in these models, our five-level healthcare provider advice model was used to ensure model stability. To explore the dose/response relationship between healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain, we used our seven-level healthcare provider advice variable; due to limited sample sizes within some levels, we were unable to stratify by prepregnancy BMI category and therefore adjusted for this variable. IOM-consistent healthcare provider advice was considered the referent for all models.

We conducted three sensitivity analyses. First, we assessed effect modification between state and healthcare provider advice by testing an interaction term in an unstratified model. Second, we excluded women with hypertensive or diabetic conditions before or during pregnancy as these may influence healthcare provider advice and/or gestational weight gain. Specifically, women with hypertensive conditions may gain weight related to edema,3 while women with diabetic conditions likely receive additional nutritional advice to control glucose levels, which may influence weight gain.20 Finally, to assess the influence of missing data, we used multiple imputation by fully conditional specification to generate five data sets with complete information on our exposure, outcome, and covariates of interest. We included all analysis variables in the imputation models and additionally included state, survey weight, and stratum indicators to account for survey design characteristics.21 Multiple imputation data sets were generated using SAS PROC MI and were analyzed using SUDAAN procedures accounting for imputations.22,23

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 with SAS-callable SUDAAN 11 to account for the complex sample design and weights utilized by PRAMS. Statistical significance was considered p < 0.05.

Results

Compared with women included in this analysis, a significantly smaller proportion of excluded women reported receiving IOM-consistent healthcare provider advice (17.4% vs. 26.3%), whereas a higher proportion reported not receiving advice (41.5% vs. 26.0%). Included and excluded women did not differ significantly by gestational weight gain or prepregnancy BMI category; however, compared to those included, a significantly larger proportion of excluded women were non-Hispanic black or Hispanic, had less than 12 years of education, were enrolled in WIC, did not smoke during pregnancy, entered prenatal care after the first trimester, or were nonmarried (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Women Excluded and Included from Analysis

| Excluded (n = 1475a) | Included (n = 7125a) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Na | % (SE)b | Na | % (SE)b | p |

| Gestational weight gain | 531 | ||||

| Inadequate | 147 | 31.9 (4.1) | 1707 | 22.6 (0.9) | 0.105 |

| Appropriate | 158 | 27.0 (3.6) | 2409 | 31.5 (0.9) | |

| Excessive | 226 | 41.1 (4.0) | 3009 | 45.9 (1.1) | |

| Healthcare provider advice | 1049 | ||||

| Advice started below recommendation | 78 | 6.7 (1.3) | 1009 | 15.5 (0.8) | 0.000 |

| IOM consistent | 178 | 17.4 (2.1) | 1967 | 26.3 (0.9) | |

| Advice ended above recommendation | 123 | 11.0 (1.8) | 1310 | 18.3 (0.8) | |

| Advice not remembered | 277 | 23.5 (2.3) | 949 | 13.9 (0.8) | |

| Advice not received | 393 | 41.5 (2.8) | 1890 | 26.0 (0.9) | |

| Prepregnancy body mass index | 988 | ||||

| Underweight | 51 | 3.8 (1.0) | 341 | 3.8 (0.4) | 0.983 |

| Normal weight | 517 | 52.6 (2.9) | 3757 | 52.0 (1.1) | |

| Overweight | 223 | 23.0 (2.5) | 1711 | 24.1 (0.9) | |

| Obese | 197 | 20.6 (2.4) | 1316 | 20.1 (0.9) | |

| Age (years) | 1474 | ||||

| Younger than 19 | 252 | 10.6 (1.3) | 775 | 8.2 (0.5) | 0.338 |

| 20–24 | 342 | 22.4 (2.0) | 1694 | 23.8 (0.9) | |

| 25–29 | 389 | 29.4 (2.2) | 2169 | 30.7 (1.0) | |

| 30 or older | 491 | 37.6 (2.3) | 2487 | 37.2 (1.0) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 1475 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 705 | 39.7 (2.3) | 5139 | 65.4 (1.0) | 0.000 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 246 | 23.0 (2.2) | 659 | 14.4 (0.9) | |

| Hispanic | 430 | 29.6 (2.1) | 1013 | 14.7 (0.7) | |

| Other | 94 | 7.6 (1.3) | 314 | 5.4 (0.5) | |

| Education (years) | 1303 | ||||

| Less than 12 | 425 | 28.0 (2.2) | 1091 | 13.8 (0.7) | 0.000 |

| 12 | 361 | 29.8 (2.4) | 1766 | 24.4 (0.9) | |

| More than 12 | 517 | 42.2 (2.5) | 4268 | 61.8 (1.0) | |

| Parity | 1433 | ||||

| 0 | 603 | 37.3 (2.3) | 3065 | 39.1 (1.0) | 0.465 |

| 1 or more | 830 | 62.7 (2.3) | 4060 | 60.9 (1.0) | |

| WIC enrollment | 1467 | ||||

| Yes | 899 | 61.5 (2.3) | 3182 | 46.5 (1.0) | 0.000 |

| No | 568 | 38.5 (2.3) | 3943 | 53.5 (1.0) | |

| Smoking status during pregnancy | 1385 | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 1144 | 85.7 (1.7) | 5501 | 79.0 (0.9) | 0.001 |

| Quitter | 113 | 8.4 (1.3) | 819 | 11.3 (0.7) | |

| Smoker | 128 | 5.9 (1.1) | 805 | 9.7 (0.7) | |

| First trimester prenatal care | 1336 | ||||

| Yes | 1016 | 77.0 (2.1) | 6040 | 86.4 (0.7) | 0.000 |

| No | 320 | 23.0 (2.1) | 1085 | 13.6 (0.7) | |

| Marital status | 1459 | ||||

| Married | 832 | 57.4 (2.4) | 4881 | 67.9 (1.0) | 0.000 |

| Nonmarried | 627 | 42.6 (2.4) | 2244 | 32.1 (1.0) | |

| Hypertensive conditions | 1475 | ||||

| Yes | 181 | 13.1 (1.7) | 956 | 11.5 (0.7) | 0.399 |

| No | 1294 | 86.9 (1.7) | 6169 | 88.5 (0.7) | |

| Diabetic disease | 1475 | ||||

| Yes | 175 | 10.8 (1.4) | 649 | 8.8 (0.6) | 0.200 |

| No | 1300 | 89.2 (1.4) | 6476 | 91.2 (0.6) | |

Women delivering full-term, singleton infants in Colorado, Georgia, Maine, and Utah in 2010–2011 were eligible for analysis. Women were excluded for having missing or implausible values for gestational weight gain, healthcare provider advice, or other covariates of interests. Women with advice starting below and ending above the IOM recommendation were also excluded due to insufficient sample sizes. Please see article for additional details about inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Based on nonweighted data.

Based on weighted data.

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

IOM, Institute of Medicine; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Overall, 26.3% of women reported receiving healthcare provider advice consistent with the 2009 IOM recommendations, whereas 15.5% received advice that started below recommendations, 18.3% received advice that ended above recommendations, 13.9% did not remember advice, and 26.0% did not receive advice (Table 2). The proportion of women who reported receiving IOM-consistent advice varied by all maternal characteristics (p < 0.05), except for diabetic disease (Table 2). Notably, compared with women in other prepregnancy BMI categories, more underweight and normal weight women reported receiving advice that started below recommendations, whereas more overweight women received advice ending above recommendations; underweight women had the highest proportion of IOM-consistent advice. The most commonly reported advised weight gain range was 25–35 pounds for underweight, normal weight, and overweight women; 15–20 pounds was most commonly advised for obese women (data not shown).

Table 2.

Healthcare Provider Advice Relative to 2009 Institute of Medicine Recommendations by Maternal Demographic Characteristics

| Advice started below recommendation | IOM consistent | Advice ended above recommendation | Advice not remembered | Advice not received | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | % (SE)a | % (SE)a | % (SE)a | % (SE)a | % (SE)a | p |

| Total | 15.5 (0.8) | 26.3 (0.9) | 18.3 (0.8) | 13.9 (0.8) | 26.0 (0.9) | |

| Prepregnancy body mass index | ||||||

| Underweight | 22.3 (4.0) | 37.9 (4.4) | 1.9 (0.8) | 13.9 (3.0) | 24.0 (4.4) | 0.000 |

| Normal weight | 24.0 (1.3) | 29.0 (1.2) | 8.9 (0.8) | 12.8 (1.0) | 25.3 (1.2) | |

| Overweight | 4.9 (1.1) | 18.1 (1.5) | 34.0 (2.1) | 14.8 (1.6) | 28.2 (2.0) | |

| Obese | 5.2 (1.2) | 26.9 (2.2) | 26.9 (2.2) | 15.4 (2.0) | 25.6 (2.2) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Younger than 19 | 20.6 (3.0) | 21.6 (2.4) | 23.1 (3.2) | 15.9 (2.2) | 18.9 (2.3) | 0.036 |

| 20–24 | 16.1 (1.8) | 23.5 (1.8) | 19.5 (1.7) | 13.4 (1.6) | 27.5 (2.2) | |

| 25–29 | 15.9 (1.5) | 27.2 (1.5) | 17.6 (1.4) | 14.8 (1.5) | 24.6 (1.6) | |

| 30 or older | 13.8 (1.2) | 28.4 (1.5) | 17.0 (1.3) | 13.0 (1.2) | 27.8 (1.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 15.4 (1.0) | 28.3 (1.0) | 17.9 (0.9) | 11.0 (0.8) | 27.3 (1.1) | 0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 15.6 (2.8) | 18.7 (3.0) | 22.2 (3.2) | 19.3 (2.9) | 24.2 (3.2) | |

| Hispanic | 16.2 (1.9) | 26.7 (2.0) | 16.7 (1.8) | 18.7 (2.1) | 21.6 (2.0) | |

| Other | 15.8 (3.5) | 20.7 (3.2) | 16.2 (3.2) | 20.4 (4.0) | 26.9 (4.3) | |

| Education (years) | ||||||

| Less than 12 | 14.1 (2.1) | 20.1 (1.9) | 17.0 (2.2) | 22.6 (2.6) | 26.3 (2.7) | 0.000 |

| 12 | 15.9 (1.8) | 21.5 (1.7) | 17.4 (1.7) | 15.8 (1.7) | 29.3 (2.2) | |

| More than 12 | 15.7 (1.0) | 29.6 (1.1) | 18.9 (1.0) | 11.2 (0.9) | 24.7 (1.1) | |

| Parity | ||||||

| 0 | 16.6 (1.3) | 29.4 (1.4) | 22.6 (1.4) | 11.9 (1.1) | 19.6 (1.3) | 0.000 |

| 1 or more | 14.8 (1.0) | 24.3 (1.1) | 15.5 (1.0) | 15.2 (1.1) | 30.2 (1.2) | |

| WIC enrollment | ||||||

| Yes | 16.2 (1.3) | 23.1 (1.3) | 18.3 (1.3) | 17.8 (1.4) | 24.6 (1.5) | 0.000 |

| No | 15.0 (1.0) | 29.0 (1.1) | 18.3 (1.0) | 10.5 (0.8) | 27.3 (1.1) | |

| Smoking status during pregnancy | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 15.2 (0.9) | 26.7 (1.0) | 17.4 (0.9) | 14.4 (0.9) | 26.3 (1.0) | 0.001 |

| Quitter | 16.4 (2.7) | 29.3 (2.8) | 24.9 (2.9) | 12.4 (2.2) | 17.0 (2.3) | |

| Smoker | 17.4 (2.9) | 19.6 (2.6) | 17.9 (2.7) | 11.1 (2.3) | 34.1 (3.7) | |

| First trimester prenatal care | ||||||

| Yes | 15.8 (0.9) | 27.3 (1.0) | 18.4 (0.9) | 13.2 (0.8) | 25.3 (1.0) | 0.003 |

| No | 14.1 (1.9) | 19.7 (1.9) | 17.4 (2.2) | 18.2 (2.3) | 30.6 (2.4) | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 14.5 (0.9) | 28.5 (1.0) | 18.5 (0.9) | 11.9 (0.8) | 26.5 (1.0) | 0.000 |

| Nonmarried | 17.7 (1.7) | 21.6 (1.6) | 17.8 (1.6) | 18.1 (1.7) | 24.9 (1.9) | |

| Hypertensive conditions | ||||||

| Yes | 10.1 (2.0) | 27.0 (2.8) | 20.8 (2.5) | 18.4 (2.8) | 23.7 (2.7) | 0.028 |

| No | 16.3 (0.9) | 26.2 (0.9) | 17.9 (0.9) | 13.3 (0.8) | 26.3 (1.0) | |

| Diabetic disease | ||||||

| Yes | 13.4 (2.5) | 21.7 (2.9) | 18.8 (3.0) | 17.9 (3.0) | 28.1 (3.6) | 0.337 |

| No | 15.8 (0.9) | 26.7 (0.9) | 18.2 (0.8) | 13.5 (0.8) | 25.8 (0.9) | |

Based on weighted data.

Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

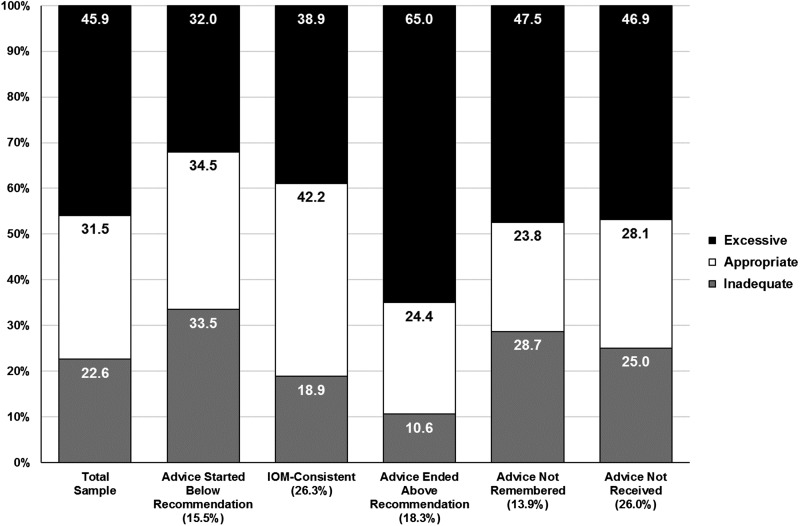

Figure 2 illustrates the bivariate association between women's report of healthcare provider advice and inadequate, appropriate, or excessive gestational weight gain. Overall, 31.5% of women had appropriate weight gain, whereas 22.6% had inadequate and 45.9% had excessive gain. Inadequate weight gain was highest among women who reported receiving advice that started below recommendations (33.5%), whereas excessive weight gain was highest among those who received advice that ended above recommendations (65.0%). Among women who reported receiving IOM-consistent advice, 42.2% had appropriate gestational weight gain.

FIG. 2.

Proportion of women with inadequate, appropriate, or excessive gestational weight gain, overall and by healthcare provider advice.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between women's report of healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) were not notably different; thus, adjusted analyses are presented below.

Adjusted associations between women's report of healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain, stratified by prepregnancy BMI category, are presented in Table 3; IOM-consistent advice was considered the referent. Underweight and normal weight women who reported receiving healthcare provider advice that started below recommendations were more likely to have inadequate gestational weight gain (PR 2.22, 95% CI 1.29–3.82 and PR 1.57, 95% CI 1.23–2.02, respectively). Normal weight, overweight, and obese women who reported receiving advice that ended above recommendations were more likely to have excessive weight gain (normal weight: PR 1.36, 95% CI 1.08–1.72; overweight: PR 1.42, 95% CI 1.19–1.71; and obese: PR 1.38, 95% CI 1.09–1.74).

Table 3.

Adjusted Associations Between Healthcare Provider Advice and Gestational Weight Gain, Stratified by Prepregnancy Body Mass Index Category

| Underweight (n = 341,a3.8%b) | Normal weight (n = 3757,a52.0%b) | Overweight (n = 1711,a24.1%b) | Obese (n = 1316,a20.1%b) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate weight gain | Excessive weight gain | Inadequate weight gain | Excessive weight gain | Inadequate weight gain | Excessive weight gain | Inadequate weight gain | Excessive weight gain | |

| Healthcare provider advice | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) |

| Advice started below recommendation | 2.22 (1.29–3.82) | —c | 1.57 (1.23–2.02) | 0.90 (0.71–1.13) | 1.88 (0.87–4.05) | 1.32 (1.01–1.74) | 1.54 (0.86–2.74) | 0.69 (0.35–1.39) |

| IOM consistent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent | Referent |

| Advice ended above recommendation | —c | —c | 0.82 (0.51–1.31) | 1.36 (1.08–1.72) | 0.58 (0.28–1.20) | 1.42 (1.19–1.71) | 0.49 (0.27–0.89) | 1.38 (1.09–1.74) |

| Advice not remembered | 1.87 (1.03–3.41) | —c | 1.50 (1.08–2.07) | 1.19 (0.94–1.51) | 1.26 (0.58–2.74) | 1.29 (1.04–1.61) | 1.01 (0.59–1.72) | 1.18 (0.86–1.62) |

| Advice not received | 1.99 (1.11–3.56) | 2.08 (1.01–4.29) | 1.30 (0.99–1.70) | 1.09 (0.90–1.31) | 2.03 (1.12–3.68) | 1.23 (1.01–1.50) | 0.76 (0.49–1.18) | 1.28 (1.01–1.62) |

Results are adjusted for covariates listed in Table 2. Bold indicates statistically significant associations.

Based on nonweighted data.

Based on weighted data.

Unable to estimate due to small sample sizes.

CI, confidence interval; PR, prevalence ratio.

Underweight and normal weight women who reported not remembering advice more likely to have inadequate weight gain (PR 1.87, 95% CI 1.03–3.41 and PR 1.50, 95% CI 1.08–2.07, respectively), whereas overweight women who did not remember advice were more likely to have excessive gain (PR 1.29, 95% CI 1.04–1.61) (Table 3). Underweight and overweight women who reported not receiving advice were more likely to have both inadequate (PR 1.99, 95% CI 1.11–3.56 and PR 2.03, 95% CI 1.12–3.68, respectively) and excessive weight gain (PR 2.08, 95% CI 1.01–4.29 and PR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01–1.50, respectively); obese women who did not receive advice were also more likely to have excessive weight gain (PR 1.28, 95% CI 1.01–1.62).

We used our expanded healthcare provider advice variable to explore the dose/response relationship between women's report of healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain among women in all prepregnancy BMI categories (Table 4); IOM-consistent advice was considered the referent. Women who reported receiving advice that started and ended below recommendations and women who received advice that started below and ended within recommendations were more likely to have inadequate gestational weight gain (PR 1.81, CI 1.28–2.55 and PR 1.49, CI 1.19–1.88, respectively); associations were stronger for women who received advice that started and ended below recommendations. Women who reported receiving advice that started and ended above recommendations and women who received advice that started within, but ended above recommendations were more likely to have excessive gestational weight gain (PR 1.51, CI 1.22–1.86 and PR 1.36, CI 1.19–1.55, respectively); associations were stronger for women who received advice that started and ended above recommendations.

Table 4.

Adjusted Associations Between Healthcare Provider Advice and Gestational Weight Gain

| Inadequate weight gain | Excessive weight gain | |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare provider advice | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) |

| Advice started below, ended below recommendation | 1.81 (1.28–2.55) | 0.94 (0.67–1.33) |

| Advice started below, ended within recommendation | 1.49 (1.19–1.88) | 0.96 (0.81–1.15) |

| IOM consistent | Referent | Referent |

| Advice started within, ended above recommendation | 0.69 (0.48–1.00) | 1.36 (1.19–1.55) |

| Advice started above, ended above recommendation | 0.64 (0.32–1.27) | 1.51 (1.22–1.86) |

| Advice not remembered | 1.31 (1.02–1.70) | 1.22 (1.05–1.41) |

| Advice not received | 1.26 (1.02–1.56) | 1.17 (1.04–1.32) |

Results are adjusted for covariates listed in Table 2. Bold indicates statistically significant associations.

Results of our sensitivity analyses revealed no meaningful differences in associations between women's report of healthcare provider advice and gestational weight gain when testing for effect modification by state or when excluding women with hypertensive or diabetic conditions; results from imputed and complete case analyses were also not meaningfully different (data not shown).

Discussion

Using population-based data representative of four states, we found only 26.3% of women reported receiving healthcare provider advice consistent with 2009 IOM gestational weight gain recommendations. Similar to studies examining previous IOM recommendations,7,9 healthcare provider advice below or above recommendations was associated with inadequate or excessive gestational weight gain, respectively; we extend previous findings by noting that some associations varied by prepregnancy BMI category. Furthermore, we found the risk of inadequate or excessive weight gain increased as provider advice deviated further from recommendations, suggesting a dose/response relationship. Our findings underscore the importance of IOM-consistent healthcare provider advice to promote appropriate gestational weight gain.

Our finding that only one-in-four women in 2010–2011 reported receiving IOM-consistent advice and another one-in-four reported receiving no advice suggests that improved awareness and/or knowledge of the 2009 IOM recommendations may be needed among healthcare providers. A survey of obstetrician/gynecologists and maternal/fetal medicine specialists conducted in 2012–2014 indicated that 82% were aware of 2009 IOM recommendations and 79% used prepregnancy BMI to modify their weight gain recommendations to patients24; however, this survey did not report on clinicians' knowledge of the weight gain ranges as recommended by the IOM. A nationwide survey of obstetrics/gynecology and family medicine residents in 2010 found 6% correctly identified IOM-consistent gestational weight gain ranges.25 A small, single-clinic study in 2016 found that obstetricians/gynecologists', nurse practitioners', and nurse midwives' knowledge of IOM-consistent weight gain ranges varied by prepregnancy BMI category, from 42% identifying the IOM-consistent range for obese women to 83% for normal weight women.26 Variability in healthcare providers' knowledge of the recommended weight gain ranges, and the observation that most are familiar with the recommended range for normal weight women, may partially explain our finding that 25–35 pounds was the most frequently reported advised weight gain range for all but obese women. In addition to limited awareness or knowledge around the 2009 IOM recommendations, healthcare providers may experience barriers that hinder counseling about gestational weight gain. Insufficient training on nutrition and weight-related counseling, sensitivity around addressing weight-related topics, and perceptions that counseling is ineffective are barriers that have been reported by healthcare providers; addressing barriers may allow providers to feel more prepared to provide IOM-consistent advice.27

Notably, among women who reported receiving IOM-consistent advice, only 42% had appropriate gestational weight gain; thus, additional counseling and behavior-change strategies may be needed to help women achieve appropriate weight gain. A 2013 Committee Opinion from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists specifically recommended healthcare providers discuss appropriate diet and physical activity, in addition to gestational weight gain, at the initial prenatal care visit and periodically throughout pregnancy.28 Importantly, this recommendation is supported by a recent systematic review that found dietary and physical activity counseling was an effective intervention strategy for preventing excessive gestational weight gain.29 Most women require no additional calories in the first trimester and an additional 340 and 450 calories a day in the second and third trimester, respectively, to support the metabolic demands of pregnancy.3 Women can use the USDA SuperTracker to identify foods that meet calorie needs30; however, for some women, referral to a dietitian may be needed to achieve dietary goals that promote appropriate gestational weight gain.3 Most pregnant women are recommended to achieve 150 minutes per week of moderate to intense physical activity, such as brisk walking.31,32 In primary care settings, physical activity prescriptions that include details of frequency, duration, and intensity have been found to promote physical activity.33 Moreover, studies among nonpregnant populations have found that frequent (i.e., at least weekly) self-monitoring of weight is an effective strategy to promote weight control34; thus, the IOM has promoted self-monitoring of weight during pregnancy as a tool to promote appropriate weight gain.33 Routine self-monitoring of weight gain that begins early in pregnancy allows for detection of inadequate or excessive gain when small, corrective changes can be made. Self-monitoring may also create opportunities for women and their healthcare providers to discuss strategies that may promote appropriate weight gain.33,34 Weight gain trackers that are specific to a woman's prepregnancy BMI are available online.35

Aside from patient-centered strategies, public health campaigns that address social norms and raise awareness about benefits of appropriate gestational weight gain may be needed.33,36 Social norms around pregnancy as an opportunity to freely gain weight (sometimes summarized by the phrase “eating for two”) may encourage excessive gain by overshadowing messages from healthcare providers about appropriate dietary, physical activity, and weight gain behaviors.36 Furthermore, raising awareness about weight gain recommendations may encourage women to initiate conversations with healthcare providers about strategies to achieve appropriate weight gain.

Our study was strengthened by the use of a large, population-based data set representative of four states, which allowed us to stratify analyses by prepregnancy BMI category and explore a dose/response relationship. We were limited by our measure of healthcare provider advice, which women reported ∼4 months postpartum and may result in recall bias if influenced by actual gestational weight gain; however, this influence may be limited because weight gain was collected separately on the birth certificate and not at the same time as healthcare provider advice. Indeed, only 20% of women reported an advised weight gain range that included their actual gestational weight gain (data not shown); if recall bias were present, we would expect this proportion to be higher. Healthcare provider advice reported by women may not reflect actual advice from a healthcare provider, but information that women internalize and recall may be most important for influencing behavior.13 We were unable to distinguish advice from a physician, nurse, or combination of clinicians, nor could we assess timing or frequency of provider advice during pregnancy because these details were not collected.

We are also limited by examining healthcare provider advice 1 or 2 years after the 2009 IOM recommendations were released may not have allowed sufficient time for recommendations to translate into practice; however, current and previous recommendations differ only for obese women.37 Furthermore, healthcare provider advice in 2010–2011 may not reflect current provider practice. Our study was restricted to women delivering full-term (37–42 weeks of gestation) infants, but we were unable to control for week-specific gestational age in our regression models because this variable was unavailable. Although self-reported prepregnancy weight tends to be underreported, especially among overweight and obese women,38 studies suggest 76%–84% of women are classified into correct BMI categories using self-reported height and prepregnancy weight.38,39 Assuming prepregnancy BMI misclassification is nondifferential to healthcare provider advice, our results would likely be biased toward the null. Finally, studies indicate that the prevalence of appropriate gestational weight gain varies by state, which may be related to social or environmental factors, or different healthcare provider practices in different states.1 While we found no evidence that state modified the association between provider advice and gestational weight gain, our findings may not be generalizable to women in all states.

In conclusion, our results suggest that healthcare provider advice influences gestational weight gain; however, approximately one-in-four women in 2010–2011 reported receiving IOM-consistent advice and another one-in-four reported receiving no advice about gestational weight gain. Strategies that raise awareness of the 2009 IOM recommendations, address barriers to providing IOM-consistent advice, and broadly promote appropriate weight gain are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System Working Group members for coordinating data collection. A list of members is available at: www.cdc.gov/prams/pdf/prams-working-group.pdf. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC. N.P.D. was supported, in part, by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32-DK007734) and an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Presented at the American Society for Nutrition Scientific Sessions at Experimental Biology 2016. April 2–6, 2016. San Diego, CA.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY. Gestational weight gain—United States, 2012 and 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1215–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deputy NP, Sharma AJ, Kim SY, Hinkle SN. Prevalence and characteristics associated with gestational weight gain adequacy. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:773–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Weight gain during pregnancy: Reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein RF, Abell SK, Ranasinha S, et al. Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2017;317:2207–2225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Viswanathan M, Siega-Riz AM, Moos MK, et al. Outcomes of maternal weight gain. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2008;168:1–223 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 315: Obesity in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:671–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS, Fein SB, Schieve LA. Medically advised, mother's personal target, and actual weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:616–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrari RM, Siega-Riz AM. Provider advice about pregnancy weight gain and adequacy of weight gain. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:256–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, Whitaker KM, Yu SM, Chao SM, Lu MC. Association of provider advice and pregnancy weight gain in a predominantly Hispanic population. Womens Health Issues 2016;26:321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelan S, Phipps MG, Abrams B, Darroch F, Schaffner A, Wing RR. Practitioner advice and gestational weight gain. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:585–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stotland N, Tsoh JY, Gerbert B. Prenatal weight gain: Who is counseled? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:695–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stotland NE, Haas JS, Brawarsky P, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, Escobar GJ. Body mass index, provider advice, and target gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waring ME, Moore Simas TA, Barnes KC, et al. Patient report of guideline-congruent gestational weight gain advice from prenatal care providers: Differences by prepregnancy BMI. Birth 2014;41:353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitaker KM, Wilcox S, Liu J, Blair SN, Pate RR. Provider advice and women's intentions to meet weight gain, physical activity, and nutrition guidelines during pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:2309–2317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wrotniak BH, Dentice S, Mariano K, Salaam EM, Cowley AE, Mauro EM. Counseling about weight gain guidelines and subsequent gestational weight gain. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:819–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald SD, Pullenayegum E, Taylor VH, et al. Despite 2009 guidelines, few women report being counseled correctly about weight gain during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:333 e1–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PRAMS methodology. Available at: www.cdc.gov/prams/methodology.htm Accessed June1, 2016

- 18.Rowland ML. Self-reported weight and height. Am J Clin Nutr 1990;52:1125–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:618–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122(2 Pt 1):406–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berglund P, Heeringa SG. Multiple imputation of missing data using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Volumes 1 and 2, Release 11. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 23.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 12.1 User's Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Power ML, Schulkin J. Obstetrician/gynecologists' knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding weight gain during pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:1169–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore Simas TA, Waring ME, Sullivan GM, et al. Institute of medicine 2009 gestational weight gain guideline knowledge: Survey of obstetrics/gynecology and family medicine residents of the United States. Birth 2013;40:237–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delgado A, Stark LM, Macri CJ, Power ML, Schulkin J. Provider and patient knowledge and views of office practices on weight gain and exercise during pregnancy. Am J Perinatol 2017. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1606582 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Stotland NE, Gilbert P, Bogetz A, Harper CC, Abrams B, Gerbert B. Preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy: How do prenatal care providers approach counseling? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:807–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no. 548: Weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:210–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muktabhant B, Lawrie TA, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive weight gain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD007145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Department of Agriculture. SuperTracker. Available at: www.supertracker.usda.gov Accessed June6, 2016

- 31.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion no 267: Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:171–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). 2008. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. DHHS, Washington, DC: Available at: https://health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf Accessed December28, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Leveraging action to support dissemination of the pregnancy weight guidelines: Workshop summary. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phelan S, Jankovitz K, Hagobian T, Abrams B. Reducing excessive gestational weight gain: Lessons from the weight control literature and avenues for future research. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2011;7:641–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weight gain during pregnancy. Available at: www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-weight-gain.htm Accessed June1, 2016

- 36.Kraschnewski JL, Chuang CH. “Eating for two”: Excessive gestational weight gain and the need to change social norms. Womens Health Issues 2014;24:e257–e259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. Nutrition during pregnancy: Part I weight gain. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park S, Sappenfield WM, Bish C, Bensyl DM, Goodman D, Menges J. Reliability and validity of birth certificate prepregnancy weight and height among women enrolled in prenatal WIC program: Florida, 2005. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:851–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunner Huber LR. Validity of self-reported height and weight in women of reproductive age. Matern Child Health J 2007;11:137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.