Abstract

Introduction: Glycating stress can occur together with oxidative stress during neurodegeneration and contribute to the pathogenic mechanism. Nerve growth factor (NGF) accumulates in several neurodegenerative diseases. Besides promoting survival, NGF can paradoxically induce cell death by signaling through the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR). The ability of NGF to induce cell death is increased by nitration of its tyrosine residues under conditions associated with increased peroxynitrite formation.

Aims: Here we investigated whether glycation also changes the ability of NGF to induce cell death and assessed the ability of post-translational modified NGF to signal through the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGEs). We also explored the potential role of RAGE–p75NTR interaction in the motor neuron death occurring in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) models.

Results: Glycation promoted NGF oligomerization and ultimately allowed the modified neurotrophin to signal through RAGE and p75NTR to induce motor neuron death at low physiological concentrations. A similar mechanism was observed for nitrated NGF. We provide evidence for the interaction of RAGE with p75NTR at the cell surface. Moreover, we observed that post-translational modified NGF was present in the spinal cord of an ALS mouse model. In addition, NGF signaling through RAGE and p75NTR was involved in astrocyte-mediated motor neuron toxicity, a pathogenic feature of ALS.

Innovation: Oxidative modifications occurring under stress conditions can enhance the ability of mature NGF to induce neuronal death at physiologically relevant concentrations, and RAGE is a new p75NTR coreceptor contributing to this pathway.

Conclusion: Our results indicate that NGF–RAGE/p75NTR signaling may be a therapeutic target in ALS. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 28, 1587–1602.

Keywords: : ALS, NGF, motor neuron, RAGE, p75NTR, glycation

Introduction

Nerve growth factor (NGF), the first member of the neurotrophin family to be identified, regulates the differentiation and survival of specific neuronal populations during development. NGF also modulates neuronal plasticity and phenotypic maintenance in the mature nervous system (34, 62). NGF is synthesized as a larger precursor (pro-NGF) that is enzymatically cleaved to generate the mature neurotrophin (4). Mature NGF (hereafter referred to as NGF) exerts its functions as a noncovalent associated homodimer, which binds to and activates two types of transmembrane receptors: (i) the tropomyosin-related tyrosine kinase receptor TrkA and (ii) the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR), a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (4, 17, 31). p75NTR has no catalytic activity and exerts its actions by interacting with different adaptor proteins and coreceptors (31). In cells that express both receptors, p75NTR increases the selectivity and affinity of TrkA for NGF to promote survival, differentiation, and/or plasticity (17). However, in cells that express p75NTR in the absence of TrkA, NGF signaling promotes cell death, although high nonphysiological concentrations of the neurotrophin are required (31, 37). In contrast, pro-NGF is able to induce cell death at subnanomolar concentrations by signaling through a coreceptor complex formed by p75NTR and sortilin (41). The intrinsic ability of p75NTR to interact with different receptors on the cell surface allows the receptor to signal in response to multiple ligands and to execute a diverse array of biological functions (31).

Innovation.

The relevance of mature nerve growth factor (NGF) inducing cell death has been disregarded because unrealistic concentrations are required in vitro. We show that post-translational modifications occurring under stress conditions confer upon mature NGF the ability to induce cell death at physiologically relevant concentrations. Post-translational modified NGF signals simultaneously through the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and p75NTR, and we show for the first time evidence for the interaction of both receptors on the cell surface. The presence of modified NGF in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mice, together with the requirement of RAGE and p75NTR signaling in ALS–astrocyte-mediated neurotoxicity, suggests the therapeutic potential of targeting RAGE–p75NTR signaling in ALS.

We have previously shown that post-translational oxidative modifications regulate the ability of NGF to induce cell death. Tyrosine nitration, induced by peroxynitrite, promotes the formation of high molecular weight NGF oligomers and confers upon the mature neurotrophin the exceptional ability to induce motor neuron apoptosis at low, physiologically relevant concentrations: 10,000-fold lower than those required by native mature NGF (45). The relevance of this regulatory mechanism of NGF activity in pathological conditions is supported by the findings from two independent groups that proNGF is target of post-translational modifications in the brain of Alzheimer's disease (AD) patients and cognitive impaired aged rats (5, 6, 28). In addition to nitration (6), proNGF is also target of glycation in the brain of AD patients (28).

Protein glycation refers to the irreversible nonenzymatic modification of protein amino groups by carbonyl-containing compounds, forming adducts called advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Methylglyoxal (MG) is the most reactive glycating agent in vivo (48). It is a by-product of cellular metabolism, including glucose metabolism, ketone body metabolism, and threonine catabolism (65, 69). Glycation confers proteins the ability to signal through the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGEs). RAGE is a type I membrane protein that lacks catalytic activity and exerts its actions by interacting with different adaptor proteins (74). Similar to p75NTR activation, RAGE signaling can promote neuronal survival or death, depending on the cellular context and the type and concentration of the ligand (55, 64).

Although originally identified as the receptor for AGEs, RAGE is a pattern recognition receptor that is activated by an extensive pool of ligands (19). Both, p75NTR and RAGE are widely expressed in the central nervous system throughout development and their expression gradually decreases after birth. However, both receptors are re-expressed at high levels in pathological conditions associated with neuronal degeneration, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (10, 26, 29, 31, 33, 56).

ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease, is characterized by the progressive degeneration of motor neurons in the motor cortex, brain stem, and spinal cord. Most ALS cases are sporadic and only about 10% of the cases are inherited (familial ALS) (54). Studies using mutant Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1)-linked ALS mouse models revealed that motor neuron degeneration in ALS is a noncell autonomous process that requires damage of neighboring glial cells (24). Astrocytes, the most abundant glial type in the central nervous system, adopt a reactive phenotype and play a key role in the progression of the disease (24, 75). We have shown that reactive astrocytes induce the death of cocultured motor neurons by a mechanism involving increased NGF production and p75NTR-dependent death signaling (8, 9, 43). Moreover, p75NTR signaling has been implicated in the pathology observed in mice overexpressing hSOD1G93A, the best characterized ALS mouse model (32, 57, 61, 70).

Cultured embryonic motor neurons represent an attractive model for studying NGF-mediated neuronal death. Although they express high levels of p75NTR in the absence of TrkA, embryonic motor neuron cultures are not sensitive to NGF-induced apoptosis. We showed that NGF/p75NTR-mediated motor neuron apoptosis occurs only in the presence of surrounding glial cells producing nitric oxide or other diffusible factors capable to decrease motor neuron antioxidant defenses (43, 44). In contrast, nitrated NGF induces p75NTR-dependent motor neuron apoptosis in the absence of an exogenous flux of nitric oxide (45). In this study, we show that glycated NGF also induces the death of cultured embryonic motor neurons at physiologically relevant concentrations. Moreover, although peroxynitrite (nitration) and MG (glycation) target different amino acid residues, both induce the formation of NGF oligomers and confer upon NGF the ability to signal through p75NTR and RAGE to induce motor neuron death. We also show evidence for the presence of nitrated and glycated NGF in the spinal cord of early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice and its potential involvement in the neuronal degeneration observed in ALS cell culture models.

Results

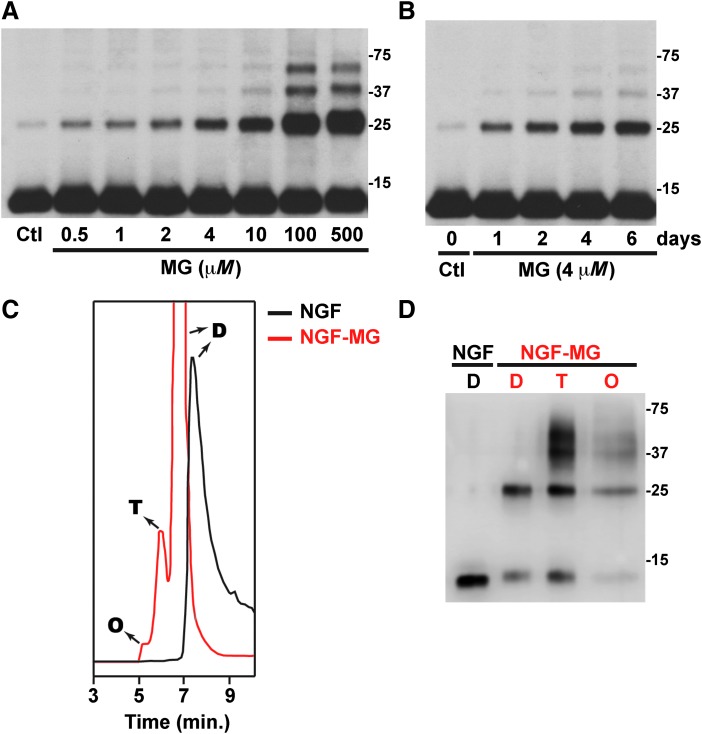

Treatment of mature NGF with MG, the most reactive glycating agent in vivo, induces, in a dose- and time-dependent manner, the formation of high molecular weight NGF oligomers (Fig. 1A, B). Our experiments were performed using purified mature NGF from mouse submaxillary glands (NGF 2.5S; #B.5017; Harlan Bioproducts). We noticed that in some of the NGF batches used, a weak band with an apparent molecular weight corresponding to NGF dimer could be detected. This band does not correspond to an incomplete cleavage of proNGF, because its intensity increases with time after incubation at 37°C (not shown) and after MG treatment in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A, B). When analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) native NGF eluted as a single peak with an apparent molecular weight corresponding to the dimer, as previously described (45). However, methylglyoxal-treated NGF (NGF-MG) eluted as three peaks with an apparent molecular weight corresponding to the dimer, tetramer, and octamer (Fig. 1C). As observed in Figure 1C, the NGF-MG dimer eluted before the native NGF dimer, suggesting conformational changes that result in a reduction of the NGF-MG dimer compactness. When aliquots from the fractions collected after SEC were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot, we observed the appearance of lower order oligomers and monomeric NGF (≈13 kDa) (Fig. 1D), suggesting that NGF oligomerization involves noncovalent interactions. Nevertheless, as observed in Figure 1D, some NGF-MG oligomers are stable in reducing SDS-PAGE gels, which might indicate a nonthiol-dependent covalent crosslinking of some subunits. However, the existence of SDS-PAGE-resistant noncovalent aggregates of other proteins has been previously reported (12, 35). Remarkably, the effect of MG treatment closely resembles the effect induced by nitration of NGF after peroxynitrite or tetranitromethane treatment, which reduces NGF dimer compactness and induces the formation of noncovalent high molecular weight oligomers (45).

FIG. 1.

Methylglyoxal induces NGF oligomerization in a dose- and time-dependent manner. (A) NGF was treated with vehicle (control; Ctl) or the indicated concentrations of MG for 72 h at 37°C, under sterile conditions. NGF was then analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot using NGF-specific antibodies. (B) NGF was treated with vehicle (Ctl) or MG (4 μM) for the indicated time (1–6 days) at 37°C, under sterile conditions. Samples were analyzed as indicated in (A). (C) NGF was treated with vehicle (NGF) or MG (500 μM; NGF-MG) for 72 h at 37°C, under sterile conditions. Samples were analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography. NGF control (black) eluted as a single peak corresponding to the dimer (D). NGF-MG (red) eluted as three peaks with an apparent molecular weight corresponding to the dimer (D), tetramer (T), and octamer (O). (D) Analysis of fractions collected in (C) by reducing SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot using NGF-specific antibodies. Noncovalent oligomerization is evidenced by the appearance of monomeric NGF (≈13 kDa) and lower order oligomers in the indicated fractions. MG, methylglyoxal; NGF, nerve growth factor

Glycation by MG is directed primarily to the guanidine group of arginine residues to initially form glycosylamine, which sequentially rearranges to form dihydroxyimidazolidine and three hydroimidazolone isomers MG-H1, MG-H2, and MG-H3 (46). MG also reacts with the ɛ-amino group of lysine residues to form Nɛ-carboxyethyl lysine (CEL) and methylglyoxal-lysine dimers (47, 65). The specific NGF residues modified by MG treatment were determined by mass spectrometry analysis. To ensure complete coverage of the NGF sequence by LC-MS/MS, multiple samples of NGF-MG were analyzed after digestion with trypsin or Glu-C.

As indicated in Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars), we detected the formation of the hydroimidazolone derivate MG-H1 (or its structural isomers MG-H2 and MG-H3; mass increment of 54 Da) on five arginine residues (R50, R59, R69, R103, and R114). We also observed the formation of the dihydroxyimidazolidine adduct (mass increment of 72 Da) at R114. Modification at this position was distinguished from the potential formation of CEL (also with a mass increment of 72 Da) at the adjacent Lysine 115 based on the presence of the b11+ ion at 1,347.64 (Supplementary Fig. S1). The fact that trypsin would likely not cleave after a CEL-modified lysine residue further supports the assignment of the modification at R114. We did not observe the formation of argpyrimidine (mass increment of 80 Da) or tetrahydropyrimidine (THP, mass increment of 144 Da), which are other minor MG-generated adducts (47, 65).

Table 1.

Summary of Nerve Growth Factor Peptides Modified by Methylglyoxal Treatment

| Peptide residues | Peptide sequence | Modification site | Glycation adduct |

|---|---|---|---|

| 42–55 | VNINNSVFRQYFFE | R50 | MG-H1/H2/H3 |

| 58–69 | CRASNPVESGCR | R59 | MG-H1/H2/H3 |

| 60–74 | ASNPVESGCRGIDSK | R69 | MG-H1/H2/H3 |

| 101–113 | FIRIDTACVCVLS | R103 | MG-H1/H2/H3 |

| 104–115 | IDTACVCVLSRK | R114 | MG-H1/H2/H3 |

| 104–115 | IDTACVCVLSRK | R114 | Dihydroxyimidazolidine |

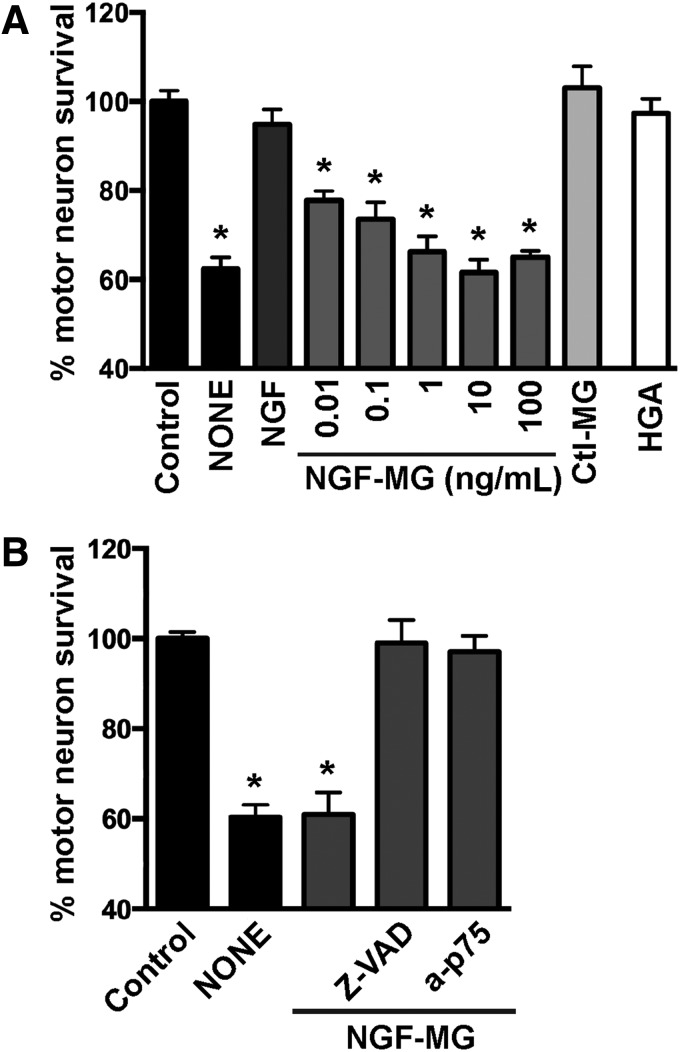

We then evaluated the biological activity of NGF-MG in primary motor neuron cultures maintained by the exogenous addition of glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF, 1 ng/mL). Under these conditions, motor neuron cultures are not sensitive to NGF-mediated cell death (43, 73) unless high concentrations of NGF (>10 ng/mL) and an exogenous flux of nitric oxide are provided (43). In contrast, NGF-MG induced motor neuron death at subpicomolar concentrations of 10 pg/mL, and independently of the presence of exogenous nitric oxide (Fig. 2A). To perform these experiments, NGF was treated with MG (2 μM or 4 μM) for 48 h at 37°C, with residual MG eliminated by ultrafiltration. No difference in the effect was observed by doubling MG concentration from 2 μM to 4 μM. To rule out a direct toxic effect of potential residual MG, a mock sample lacking NGF was processed as mentioned and used as a control (control MG in Fig. 2A). Motor neuron survival was not affected by the addition of human glycated albumin (Fig. 2A), further supporting a specific effect of glycated NGF. In addition, motor neuron death induced by NGF-MG was prevented by the general caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK and by p75NTR-blocking antibodies (Fig. 2B). These results resemble those obtained with nitrated NGF (45), suggesting that the gain in p75NTR-dependent apoptotic activity of mature NGF after glycation or nitration involves a common mechanism.

FIG. 2.

Methylglyoxal-treated NGF induces p75NTR-dependent motor neuron death. (A) Motor neuron cultures maintained with GDNF (1 ng/mL) were treated with vehicle (control), NGF (100 ng/mL), glycated human albumin (HGA; 50 ng/mL), or the indicated concentrations of methylglyoxal-treated NGF (NGF-MG). NGF was treated with MG (2 μM), and residual MG was eliminated by ultrafiltration. To rule out direct toxic effects of potential residual MG, a mock sample lacking NGF was processed as mentioned and used as a control (ctl-MG). It had no effect on motor neuron survival. Motor neuron death induced by trophic factor deprivation (NONE) was used as a control of the maximal motor neuron death observed in this culture model. (B) Motor neuron death induced by NGF-MG (10 ng/mL) was prevented by the addition of the general caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (10 μM; Z-VAD) or p75NTR-blocking antibodies (a-p75; 1:1000). Nonimmune serum was devoid of effect (not shown). For (A and B), cultures were treated with NGF-MG 16 h after plating. p75NTR-blocking antibodies were added once, 30 min before NGF-MG treatment. Z-VAD-FMK was added every 24 h. Motor neuron survival was determined 48 h after treatment. Data are expressed as percentage of control (mean ± SEM). *Significantly different from control (p ≤ 0.05). GDNF, cell-derived neurotrophic factor; NGF-MG, methylglyoxal-treated NGF

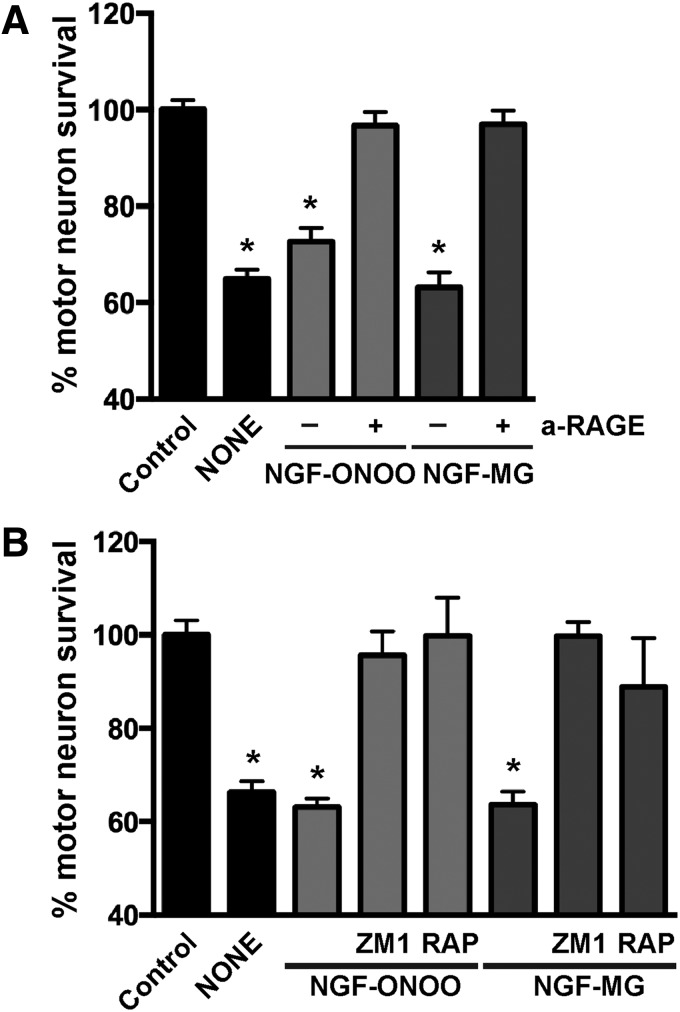

RAGE is a pattern recognition receptor able to bind multiple ligands, and most RAGE ligands are oligomeric in nature (19). Since glycation and nitration induced NGF oligomerization, we analyzed the participation of RAGE signaling in the cell death induced by post-translational modified NGF. RAGE-blocking antibodies prevented the motor neuron death induced by peroxynitrite-treated NGF or NGF-MG (Fig. 3A). A comparable protection was observed with two previously described RAGE pharmacological inhibitors, FPS-ZM1 (16) and RAP (1) (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Motor neuron death induced by nitrated or glycated NGF is RAGE signaling dependent. (A) Motor neuron cultures maintained with GDNF (1 ng/mL) were treated with vehicle (control), peroxynitrite-treated NGF (NGF-ONOO; 10 ng/mL), or NGF-MG (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of RAGE-blocking antibodies (a-RAGE; 15 μg/mL). Motor neuron death induced by NGF-ONOO or NGF-MG was prevented by RAGE-blocking antibodies. Preimmune IgG had no effect (not shown). (B) Motor neuron cultures were treated with vehicle (control), NGF-ONOO (100 ng/mL), or NGF-MG (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of specific RAGE inhibitors FPS-ZM1 (ZM1; 100 nM) or RAP (2 μM). For (A and B), motor neuron death induced by trophic factor deprivation was used as a control (NONE). Cultures were treated 16 h after plating. RAGE-blocking antibodies and inhibitors were added once, 30 min before treatment. Motor neuron survival was determined 48 h after treatment. Data are expressed as percentage of control (mean ± SEM). *Significantly different from control (p ≤ 0.05). RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products.

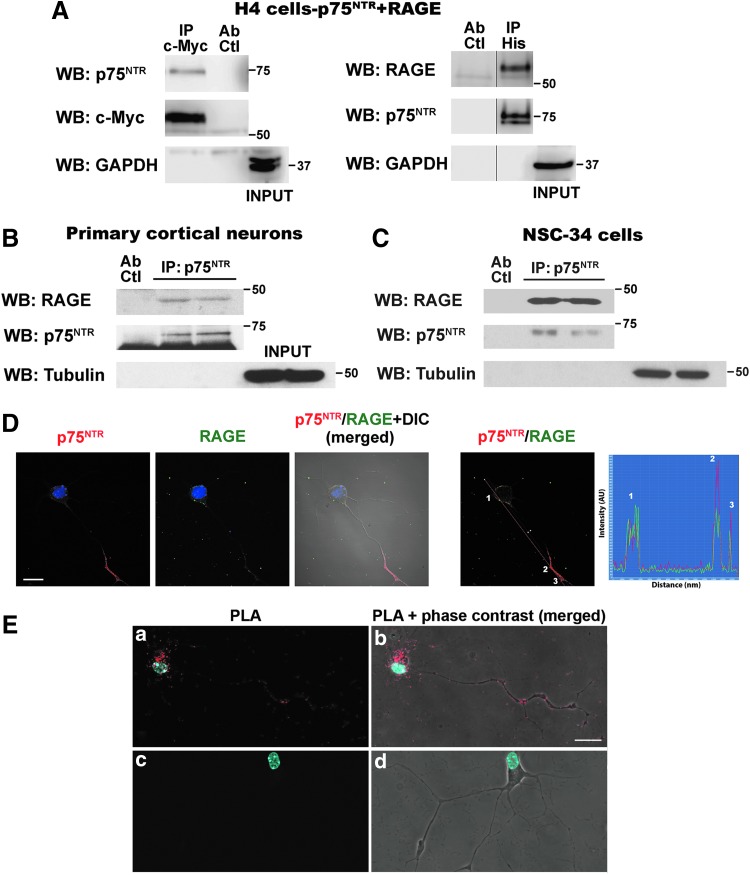

Blocking only either p75NTR or RAGE completely prevented motor neuron death induced by nitrated or glycated NGF, suggesting a functional interaction of both receptors either by independent activation by the ligand or by the simultaneous binding of post-translational modified NGF to a RAGE–p75NTR complex. This, together with the fact that p75NTR relies on its ability to interact with different receptors on the cell surface to elicit its broad array of biological functions (3), led us to evaluate the potential interaction between p75NTR and RAGE. Crosslinking and coimmunoprecipitation studies indicated that p75NTR and RAGE interact in the cell surface of H4 neuroglioma cells (Fig. 4A) or HEK293 cells (not shown) co-overexpressing a c-Myc-tagged version of RAGE and a His-tagged version of p75NTR. We also confirmed RAGE–p75NTR interaction in primary cortical neurons and NSC-34 motor neuron-like cells, expressing endogenous levels of the receptors (Fig. 4B, C). Owing to the low yield of motor neurons per spinal cord, RAGE–p75NTR interaction in primary motor neuron cultures was confirmed using an in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA), which allows to observe and determine, in fixed cultured cells, the subcellular localization of protein–protein interactions at single-molecule resolution (63). Colocalization of p75NTR and RAGE immunofluorescence was observed in cultured motor neurons (Fig. 4D). Using the same set of primary antibodies against the extracellular domain of p75NTR and RAGE, the in situ PLA detected RAGE–p75NTR interaction in the soma and neurites of cultured motor neurons (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

RAGE and p75NTR interact at the cell surface. Cells were incubated for 30 min at room temperature with the membrane-impermeable reducible crosslinker DTSSP. After lysis, RAGE or p75NTR was immunoprecipitated. Precipitated complexes were analyzed by reducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot (WB) using antibodies against p75NTR, c-Myc, RAGE, GAPDH, or tubulin. (A) Immunoprecipitation (IP) in extracts from H4 neuroglioma cells co-overexpressing c-Myc-tagged RAGE and His-tagged p75NTR. Left: IP c-Myc-tag; WB p75NTR. Right: IP His tag; WB RAGE. (B and C) IP p75NTR; WB RAGE in primary cortical neurons (B) or NSC-34 cells (C). IP in two independent biological replicates is shown. For (A–C), IP specificity was confirmed using antibodies against GAPDH (A) or tubulin (B and C). These abundant proteins were not pulled down after immunoprecipitation and were detected only in the sample before IP (INPUT). Ab Ctl: antibody control, mock sample including the antibody in the absence of protein extract. This control was included to confirm that the RAGE immunoreactive band does not correspond to the unspecific detection of the immunoglobulin heavy chain, both of similar apparent molecular weight. Full-length images of the membranes are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. (D) Image of RAGE–p75NTR colocalization as determined by immunofluorescence using antibodies against the extracellular domain of p75NTR and RAGE. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The right panel shows the distribution of fluorescence intensity of p75NTR (red) and RAGE (green) staining across the indicated path (red line). The distribution of peak fluorescence intensity corresponding to p75NTR and RAGE staining suggests spatial colocalization. Scale bar, 20 μm. (E) Images showing RAGE–p75NTR interaction in primary motor neurons by in situ PLA. Motor neuron cultures were stained with antibodies against the extracellular domain of p75NTR and RAGE (same antibodies as in D) and developed using DuoLink kit. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The signal from each detected pair of PLA probes is seen as an individual red fluorescent spot. A representative image showing RAGE–p75NTR interaction in the soma and neurites of motor neurons is shown in (a) and (b). A representative image of the negative control omitting one primary antibody is shown in (c) and (d). Scale bar, 20 μm.

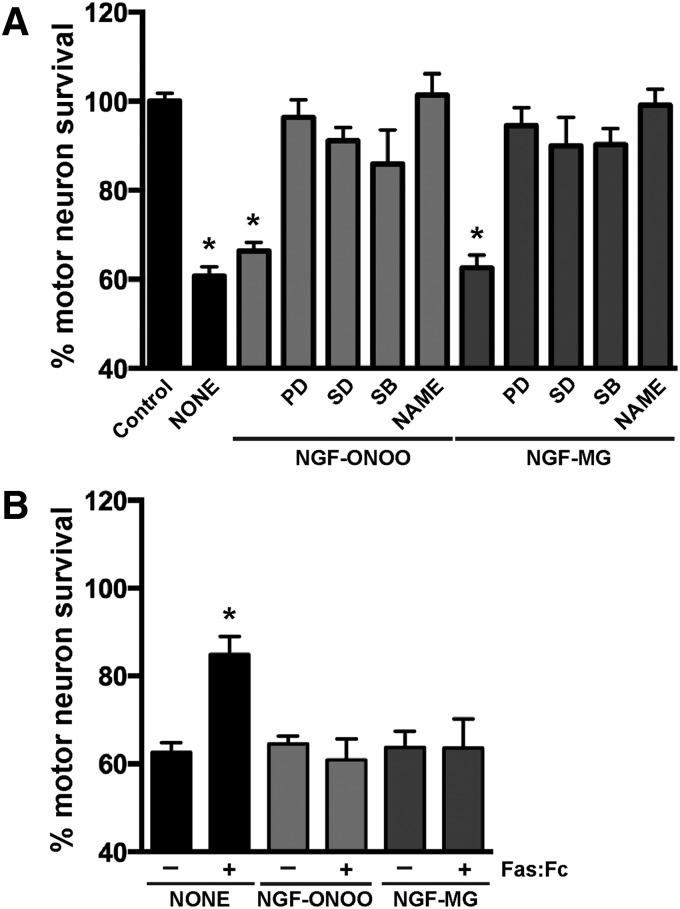

Motor neuron death induced by different stimuli, including trophic factor deprivation and nitric oxide donors, involves activation of Fas by endogenous Fas ligand (FasL) (20, 51, 53). FasL/Fas signaling in motor neurons triggers a cell-type specific death pathway involving p38 MAP kinase activation that leads to increased nitric oxide production (52). Since RAGE activation has been shown to increase FasL expression in other cell types (67, 74), we tested the potential activation of this death pathway by post-translational modified NGF. Motor neuron death induced by nitrated or glycated NGF was prevented by the addition of three different p38 MAP kinase inhibitors and by the general nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor Nω-nitro l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) (Fig. 5A). However, blocking Fas/FasL signaling by the addition of the specific antagonist Fas:Fc did not prevent motor neuron death induced by nitrated or glycated NGF (Fig. 5B). As a control, we verified that Fas:Fc rescued a subpopulation of motor neurons from trophic factor deprivation-induced death, as previously described (53). Hence, motor neuron death induced by post-translational modified NGF is Fas signaling-independent but involves p38 MAP kinase activation, increased nitric oxide production and, as we previously described, peroxynitrite formation (45).

FIG. 5.

Post-translational modified NGF-induced motor neuron death involves p38 MAP kinase activation and increased nitric oxide production. (A) Motor neuron cultures maintained with GDNF (1 ng/mL) were treated with vehicle (control), peroxynitrite-treated NGF (NGF-ONOO; 100 ng/mL), or NGF-MG (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of the general NOS inhibitor l-NAME (500 μM) or the selective p38 MAPK inhibitors: PD169316 (PD; 10 μM), SD-169 (SD; 0.5 μM), and SB202190 (SB; 1 μM). Cultures were treated 16 h after plating and pretreated with the inhibitors for 1 h before post-translational modified NGF treatment. Motor neuron death induced by trophic factor deprivation was used as a control (NONE). (B) Cultures were treated as in (A) in the presence or absence of recombinant Fas:Fc (1 μg/mL). Fas:Fc prevented NONE-induced motor neuron death but had no effect on NGF-ONOO- or NGF-MG-induced neuronal death. Fas:Fc was added at the moment of plating for NONE. Motor neuron survival was determined 48 h after post-translational modified NGF treatment. Data are expressed as percentage of control (mean ± SEM). *Significantly different from control (p ≤ 0.05).

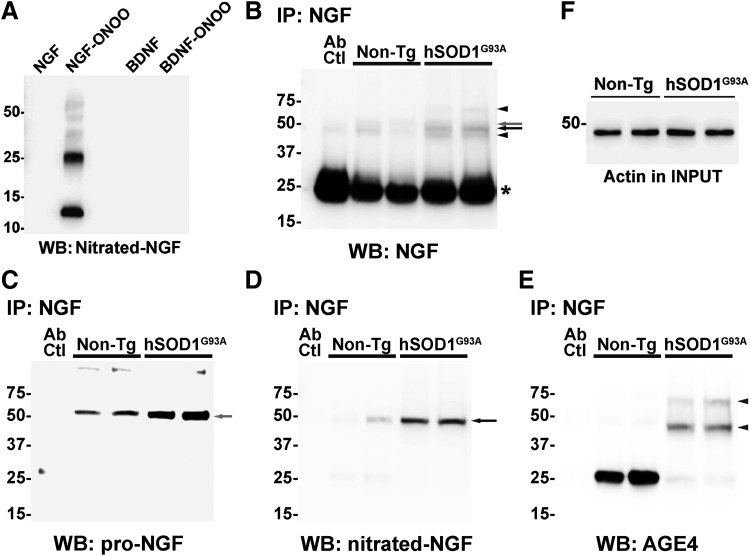

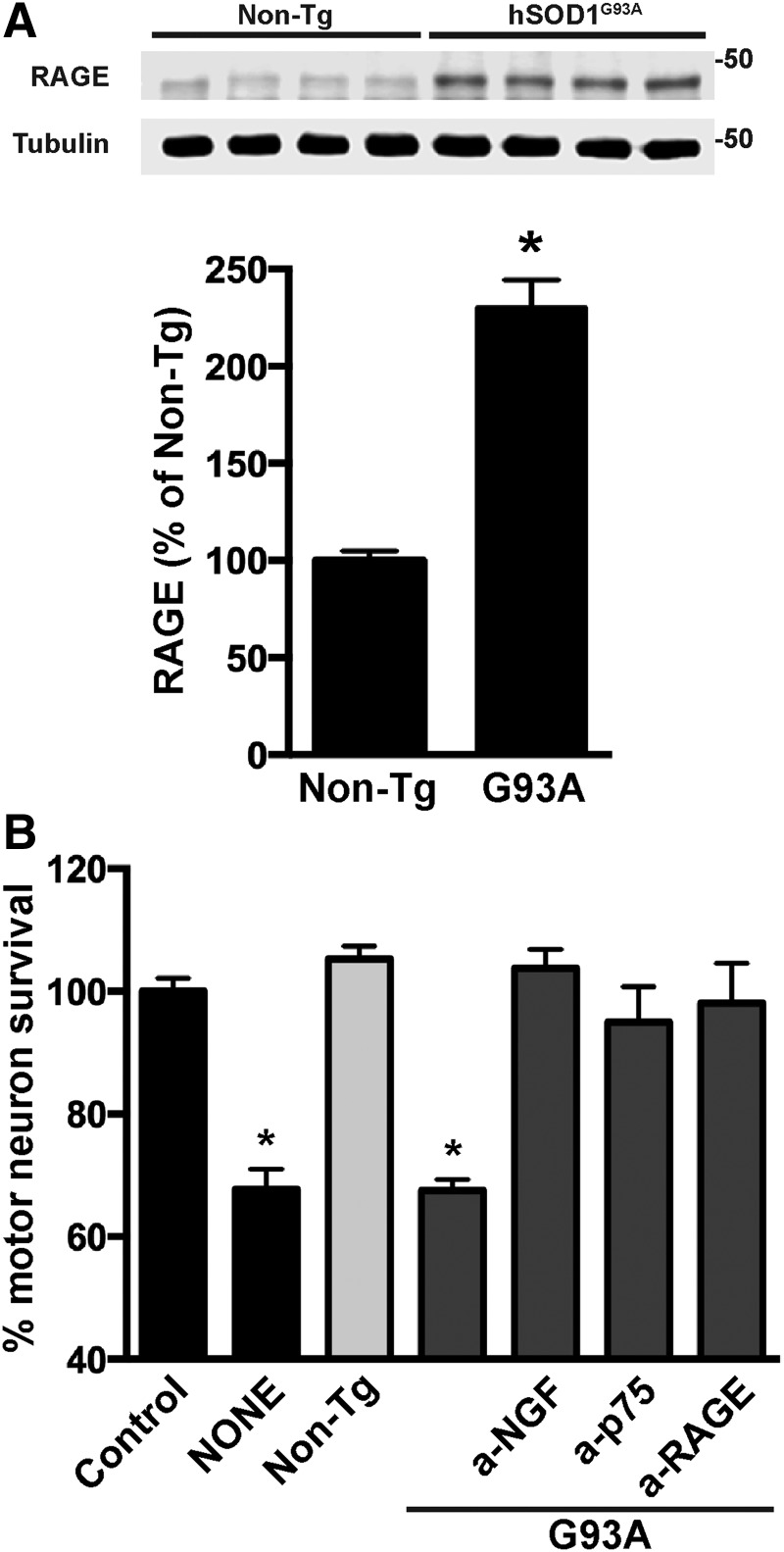

Lastly, we confirmed the presence of post-translational modified NGF in the spinal cord of early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice using antibodies against MG-derived adducts and a specific antibody against nitrated NGF that we developed. The antibody against nitrated NGF did not recognize native NGF or nitrated BDNF, other member of the neurotrophin family (Fig. 6A). After in vitro treatment with peroxynitrite, purified NGF migrates on reducing SDS-PAGE with apparent molecular weights corresponding to the monomer, dimer, trimer, tetramer, and pentamer. The antibody against nitrated NGF detected all the oligomeric forms (Fig. 6A). After immunoprecipitation using NGF-specific antibodies, we detected the presence of high molecular weight species of NGF, whereas monomeric mature NGF (≈13 kDa) was not observed in our experimental conditions (Fig. 6B). As previously reported (43), we observed increased levels of NGF in the spinal cord of ALS mice (Fig. 6B). Moreover, using an antibody against the prodomain of NGF, we confirmed the presence of proNGF in samples from both transgenic and nontransgenic mice, which migrated as a unique band with an apparent molecular weight close to 50 kDa (Fig. 6C). This result suggests the presence of oligomeric forms of NGF, which do not correspond to proNGF, in the spinal cord of ALS mice. In spinal cord extracts from hSOD1G93A mice, four NGF immunoreactive bands were observed. Strikingly, only one band (<50 kDa; likely tetramer) was detected using the specific antibody against nitrated NGF (Fig. 6D). Remarkably, the band corresponding to proNGF does not appear immunoreactive for nitrated NGF. Because MG is the most reactive glycating agent in vivo (48, 65), we reprobed the membrane with an antibody specific to MG-derived AGE and observed that NGF is also glycated in the spinal cord of ALS mice. We detected two immunoreactive bands, different from those immunoreactive for nitrated NGF or proNGF, likely corresponding to trimers and pentamers of glycated NGF (Fig. 6E). The antibody against MG-derived adducts also detected an immunoreactive band with an apparent molecular weight close to 25 kDa. Because it migrates together with the light chain of the antibody used for the immunoprecipitation, we cannot unequivocally ascribe this band to an NGF dimer. This glycated species seems to be more abundant in samples from nontransgenic mice. However, glycated higher molecular weight species of NGF were not abundant in the spinal cord of nontransgenic mice. An experimental replicate of the immunoprecipitation experiment displaying similar results is also shown in Supplementary Figure S3. We have previously shown that the increased NGF expression in the spinal cord of hSOD1G93A mice overlaps with increased p75NTR expression (43). This occurs together with increased RAGE expression (Fig. 7A).

FIG. 6.

Presence of post-translational modified NGF in the spinal cord of early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice. (A) Western blot showing the specificity of the mouse monoclonal anti-nitrated NGF antibody. The antibody recognizes peroxynitrite-treated NGF (NGF-ONOO), but does not recognize nitrated BDNF (BDNF-ONOO) nor native NGF or BDNF. (B–E) NGF was immunoprecipitated from lumbar spinal cord extracts obtained from early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice or age-matched nontransgenic (non-Tg) littermates. The immunoprecipitated complexes were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using antibodies against NGF (B), proNGF (C), nitrated NGF (D) or MG-derived AGEs (AGE4; E). Membranes were stripped and reprobed for the different antibodies. Ab Ctl: IP omitting protein extract, to determine the potential detection of the heavy and light chains of the antibody used for IP. The asterisk in (B) indicates the light chain of the IgG used for IP. (F) Actin levels in the sample before IP (INPUT). Arrows and arrowheads indicate the relative position of NGF immunoreactive bands recognized by each specific antibody in relation to the immunoreactive bands detected using the antibody against total NGF (B).

FIG. 7.

NGF present in hSOD1G93A lumbar spinal cord extracts induces the death of cultured motor neurons by signaling through p75NTR and RAGE. (A) Western blot analysis of RAGE expression in spinal cord protein extracts from early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice (G93A) or age-matched nontransgenic (non-Tg) littermates. Each lane corresponds to a different mouse. Lower panel: quantification of RAGE levels after correction by tubulin levels. Data are expressed as percentage of non-Tg (mean ± SEM). *Significantly different from non-Tg (p ≤ 0.05). (B) Primary motor neurons were isolated from the spinal cord of E12.5 hSOD1G93A embryos. Motor neuron cultures were maintained with GDNF (1 ng/mL). Cultures were treated 2 h after plating with vehicle (control) or spinal cord extracts (0.5 μg protein/mL) from early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice (G93A) or aged-matched nontransgenic littermates (non-Tg). Blocking antibodies to NGF (a-NGF; 2 μg/mL), p75NTR (a-p75; 1:1000), or RAGE (a-RAGE; 15 μg/mL) were added 30 min before treatment. Neuronal survival was determined 48 h after treatment. Motor neuron death induced by hSOD1G93A spinal cord extracts was prevented by either NGF, p75NTR, or RAGE-blocking antibodies. Preimmune IgG had no effect (not shown). Data are expressed as percentage of control (mean ± SEM). *Significantly different from control (p ≤ 0.05).

In a cell culture model, we observed that lumbar spinal cord extracts from early symptomatic ALS mice induced the death of cultured hSOD1G93A-expressing motor neurons, whereas extracts obtained from age-matched nontransgenic littermates were devoid of effect (Fig. 7B). Interestingly, motor neuron death induced by ALS extracts was completely prevented by blocking antibodies to NGF, p75NTR, or RAGE (Fig. 7B). Importantly, the NGF-blocking antibody used recognized both native and post-translational modified NGF, as evidenced by immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis (Fig. 6). These results indicate that endogenous post-translational modified NGF present in the spinal cord of ALS mice has the ability to induce the death of cultured hSOD1G93A motor neurons by signaling through p75NTR and RAGE.

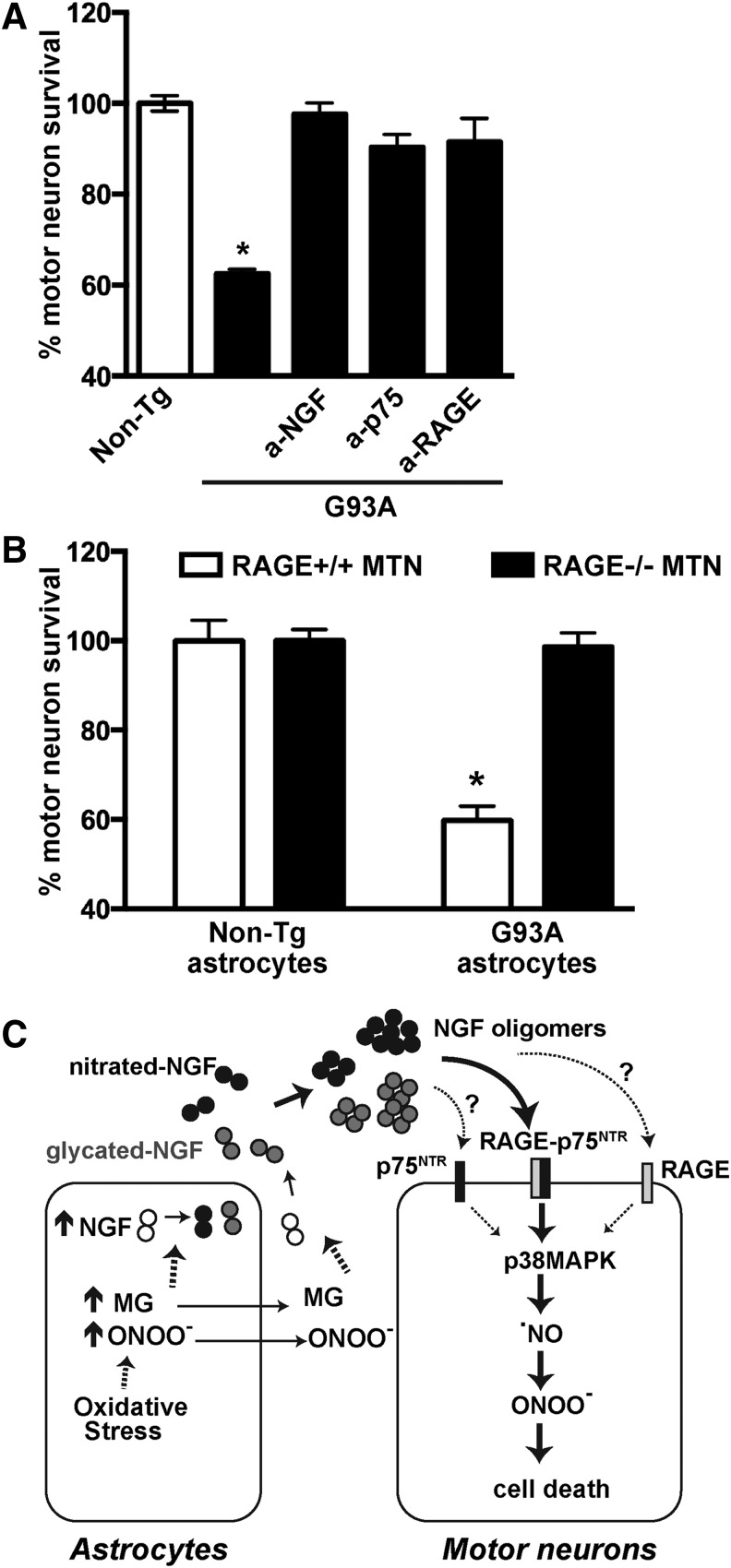

To further confirm the potential relevance of RAGE–p75NTR signaling in ALS, we employed a coculture model in which purified motor neurons are plated on top of either nontransgenic- or hSOD1G93A-astrocyte monolayers. As previously reported (39, 71), nontransgenic astrocytes support neuronal survival, whereas about 40% of motor neurons are lost when cocultured on resting astrocytes overexpressing hSOD1G93A (Fig. 8). Motor neuron death induced by hSOD1G93A astrocytes was completely prevented by the addition of either blocking antibodies that antagonize NGF, p75NTR, or RAGE signaling (Fig. 8A). The involvement of NGF and p75NTR signaling in astrocyte-mediated motor neuron loss in cocultures has been previously described (8, 18, 43). To confirm the involvement of RAGE signaling, we used motor neurons isolated from RAGE knockout mice and found that hSOD1G93A astrocytes did not induce the death of cocultured motor neurons lacking RAGE expression (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

A role for NGF, p75NTR, and RAGE signaling in the motor neuron death induced by hSOD1G93A astrocytes. (A) Nontransgenic embryonic motor neurons were plated on top of nontransgenic (non-Tg) or hSOD1G93A (G93A) astrocyte monolayers. Blocking antibodies to NGF (a-NGF; 2 μg/mL), p75NTR (a-p75; 1:1000), or RAGE (a-RAGE; 15 μg/mL) were added 2 h after motor neuron plating. Neuronal survival was determined 72 h later. Motor neuron death induced by hSOD1G93A astrocytes was prevented by NGF, p75NTR, or RAGE-blocking antibodies. Preimmune IgG had no effect (not shown). Data are expressed as percentage of motor neuron survival on top of non-Tg control astrocytes (mean ± SEM). *Significantly different from non-Tg control (p ≤ 0.05). (B) Motor neurons isolated from the spinal cord of E12.5 nontransgenic (RAGE+/+) or RAGE knockout (RAGE−/−) embryos were plated on top of nontransgenic (non-Tg) or hSOD1G93A (G93A) astrocyte monolayers. Neuronal survival was determined 72 h later. On average, a similar number of motor neurons RAGE+/+ and RAGE−/− were counted on top of nontransgenic astrocytes. hSOD1G93A astrocytes induced the death of nontransgenic motor neurons but did not alter the survival of RAGE knockout motor neurons. For each neuronal genotype, data are expressed as percentage of motor neuron survival on top of non-Tg control astrocytes (mean ± SEM). *Significantly different from its respective non-Tg control (p ≤ 0.05). (C) Schematic representation of the main results and conclusions. As supported by previous literature, reactive astrocytes in the spinal cord of hSOD1G93A mice display increased production of NGF in the presence of oxidative and glycating stress. Overwhelming of antioxidant defenses leads to increased production and accumulation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and MG, which in turn, induce NGF nitration and glycation, respectively. Because MG and peroxynitrite can diffuse across cellular membranes, post-translational modification of NGF could occur intra- or extracellularly. Both nitration and glycation induce oligomerization and confer upon NGF the ability to signal through a RAGE–p75NTR signaling complex. Signaling through RAGE–p75NTR leads to motor neuron cell death by a mechanism involving p38MAPK activation, increased production of nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite formation. The possibility of independent p75NTR and RAGE signaling in response to post-translational modified NGF was not ruled out (dashed arrows).

Discussion

Although the ability of mature NGF to induce cell death has been extensively reported, its relevance in vivo has been questioned because high concentrations, at least an order of magnitude higher than those required to promote cell survival, are required to induce apoptosis in vitro. Hence, the field has focused on the regulation of proneurotrophin cleavage as the switch regulating the prosurvival/prodeath signaling of neurotrophins (11, 21). Our results challenge this paradigm and indicate that the ability of NGF to induce cell death can also be regulated by post-translational modifications occurring under stress conditions, specifically nitration and glycation, which confer upon mature NGF the ability to signal simultaneously through RAGE and p75NTR.

We have previously shown that NGF is target of post-translational oxidative modifications induced by peroxynitrite (45). In our experiments, NGF was treated with peroxynitrite by 10 bolus additions of 1 μL each, to reach a final concentration of 1 mM. Thus, each bolus corresponds to a concentration of peroxynitrite in the micromolar range (100 μM to 143 μM taking into account the volume correction after each bolus addition). Accordingly, the rate of peroxynitrite production in vivo in specific compartments has been estimated to be as high as 50–100 μM per minute (68). Although acute short-lasting bolus exposure to peroxynitrite is not optimal to mimic the in vivo situation, it has allowed us to identify the potential NGF residues target of peroxynitrite modification and to characterize the changes in NGF biological activity after oxidative modification (45). Importantly, supporting the relevance of our in vitro results, the presence of nitrated NGF has been observed in the brain of AD patients and cognitive impaired aged rats (5, 6), and we have now detected it in the spinal cord of early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice.

Nitration of the two tyrosine residues (Tyr52 and Tyr79) present in mature NGF enhances its ability to induce p75NTR-dependent motor neuron apoptosis at subnanomolar (physiological) concentrations (45). Here we show that glycation induced by MG treatment, although it targets different amino acid residues, mimics the effects mediated by tyrosine nitration. It is worth noting that the concentration of MG used to modify NGF for the cell culture experiments is in the same range as that typically found in mammalian cells (48). Typical concentrations of MG in cells and tissues are in the range of 1–4 μM, but higher levels are observed in aging and pathological conditions (48). As observed with nitrated NGF, glycated NGF induced motor neuron death at physiologically relevant concentrations (subpicomolar range). Although peroxynitrite and MG target different amino acid residues and generate different adducts, both induce NGF oligomerization and confer upon NGF the ability to signal through p75NTR and RAGE to induce motor neuron death. This suggests that oligomerization of mature NGF could be a regulatory mechanism promoting prodeath activity toward motor neurons.

A distinctive feature of RAGE ligands is their oligomeric nature (19), and both nitration and glycation induce noncovalent NGF oligomerization [(45) and Fig. 1]. Native NGF exists in solution in a self-associating dimer–tetramer equilibrium, leading to the formation of multimers ranging up to dodecamers of NGF at high concentrations of the protein (14, 40). Furthermore, a dimer of dimers arrangement was observed in the crystal structure of mouse NGF (PDB ID: 1BTG) (23). NGF has only two tyrosine residues: both are nitration targets (45). Mass spectrometry analysis indicated that glycation by MG is directed primarily to the guanidine group of five arginine residues in NGF, giving rise to the formation of the MG-H1 adduct (or its structural isomers MG-H2 and MG-H3). Nitration lowers the pKa of the tyrosine hydroxyl moiety to near physiological pH and also makes peptides more hydrophobic when the nitrotyrosine is protonated (66), whereas the formation of the MG-H1 adduct neutralizes the positive charge of the arginine residue (47). Thus, both post-translational modifications have the potential to induce structural changes. Our results indicate that they shift the NGF equilibrium in solution toward high molecular weight oligomers, suggesting the existence of structural rearrangements that facilitate the interaction.

More than 99% of the formed MG binds reversibly to protein or glutathione (GSH) cysteine thiols (hemithioacetal adduct). Since the cellular concentration of MG is approximately 0.01% of total thiol concentration, reversible MG binding does not significantly affect cellular thiol status but helps prevent the formation of irreversible glycation adducts (47). Most of the MG generated (>99%) is detoxified by the ubiquitously expressed, GSH-dependent, glyoxalase system (47). This system involves the consecutive action of two enzymes, glyoxalase I (GLO1) and glyoxalase II (48, 65, 69). GLO1 catalyzes the rate-limiting step of the pathway, and downregulation or inhibition of the enzyme leads to increased MG levels and protein glycation (49, 65). Since GLO1 activity is directly proportional to the cellular GSH concentration (49), oxidative stress can lead to decreased MG degradation and subsequent protein glycation (48). Protein quality control systems present in every cell are fundamental to prevent the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates and maintain cellular proteostasis. These quality control systems respond to different stressors with a hormetic dose response, in which low-dose stimulation by different stressors induces an adaptative response that confers resistance and enhances survival, whereas high exposure to the stressors overwhelms the defense systems and induces cellular demise (7, 15). Accumulation of oxidative-modified proteins occurs during aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS (2, 25). When post-translational oxidative modifications induce a gain of function in a protein, the increase in activity or the appearance of a new function could allow a small fraction of the modified protein to have a significant biological effect (66). Our results indicate that nitration and glycation induce a gain in NGF prodeath activity, conferring upon the modified neurotrophin the ability to signal through RAGE–p75NTR at picomolar concentrations. Figure 8C displays a schematic representation of our main findings and conclusions.

Blocking either p75NTR or RAGE completely prevented the neuronal death induced by modified NGF, suggesting that simultaneous binding to both receptors is essential to induce death signaling. This could be explained by the interaction of both receptors to form a signaling complex, or by functional interaction at the level of the signaling cascades activated independently by each receptor in response to post-translational modified NGF. Both mechanisms, receptor heterocomplex formation and downstream signaling pathway interaction, are not mutually exclusive and RAGE–p75NTR interaction could be occurring at both levels. Although our results do not exclude the potential interaction of both receptors at the level of the signaling cascades, using two different techniques we show evidence for the endogenous formation of a RAGE–p75NTR receptor complex in four different cellular models (Fig. 4). We observed that p75NTR and RAGE interact on the cell surface even in the absence of exogenous ligand. The preassembly of receptor complexes on the cell membrane has been observed for several receptors, including p75NTR homodimers, p75NTR–sortilin heterocomplexes, and RAGE homodimers (19, 41, 72). The binding of nitrated- or glycated-NGF oligomers to the RAGE–p75NTR complex could (i) increase the relative amount of complexes, as observed for p75NTR–sortilin complexes (41); (ii) induce a conformational change in the receptor, as observed for p75NTR homodimers (72); or (iii) induce the formation of higher order oligomerization states, as observed for RAGE homodimers (19). Further studies are required to confirm or discard these possibilities.

The presence of post-translational modified NGF has been previously observed in the brain of AD patients and cognitive impaired aged rats (5, 6, 28). In these reports, nitration and glycation were adjudicated to pro-NGF, although the potential existence of high molecular weight species of post-translational modified mature NGF was not unequivocally excluded. Owing to their close molecular weight, distinction between pro-NGF and mature NGF oligomers is not always achieved in SDS-PAGE. It was shown that mature nitrated NGF has reduced ability to activate TrkA signaling and promote neuronal survival, and its presence was linked to the cognitive decline associated with aging and AD (5, 6). Together, our results suggest the potential involvement of post-translational modified NGF and RAGE–p75NTR signaling in ALS pathology. We determined the presence of post-translational modified NGF in the spinal cord of symptomatic ALS mice (Fig. 6), which coincides with increased expression of RAGE (Fig. 7) and p75NTR (43). Moreover, motor neuron death induced by ALS astrocytes or spinal cord extracts from symptomatic ALS mice was dependent on NGF and p75NTR/RAGE signaling. Blocking either NGF, p75NTR, or RAGE independently completely prevented motor neuron death, suggesting that signaling of post-translational modified NGF through both receptors is required. Nevertheless, the potential synergistic interaction of p75NTR and RAGE at the level of the signaling cascades activated independently by different receptor-specific ligands cannot be excluded. A previous report suggested the involvement of pro-NGF in the motor neuron death induced by ALS astrocytes (18). However, in the aforementioned study, total NGF immunodepletion was performed and, therefore, the involvement of post-translational modified mature NGF was not ruled out. Our data suggest that post-translational modified NGF may have a central role in this phenomenon and our results revealed the key participation of RAGE–p75NTR signaling in the motor neuron death induced by ALS astrocytes. Both receptors are expressed by spinal cord motor neurons in ALS patients and mice (10, 18, 33, 56). Since adult healthy motor neurons lack p75NTR expression (30, 76), NGF toxicity will be directed toward stressed motor neurons that re-express p75NTR. In this context, post-translational modified NGF would propagate a vicious cycle, driving progressive motor neuron death.

Although our results were obtained using a hSOD1-linked ALS mouse model, their potential translation to familial and sporadic human ALS pathology is supported by previous reports indicating that the spinal cord of ALS patients has markers of oxidative and glycating stress (2, 13, 25, 27, 59, 60), together with increased p75NTR and RAGE expression (10, 18, 26, 33, 56), which coincides with increased levels of NGF in the cerebrospinal fluid (18). Further stressing the potential role of p75NTR-death signaling in ALS pathology, it has been shown that the urinary levels of the p75NTR extracellular domain constitute a potential biomarker of disease activity and progression in ALS patients (57, 58). Despite substantial evidence for an involvement of p75NTR signaling in ALS pathology (18, 57, 61), p75NTR ablation only modestly delayed the pathology in hSOD1G93A female mice (32, 70). This modest effect could be explained by the fact that p75NTR also promotes motor neuron survival by interacting with TrkB and TrkC (22, 73), and Schwann cell migration and myelination (31). Thus, the advance of new therapies targeting p75NTR apoptotic signaling demands a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms defining its dual effects (36). These dual effects appear to be mediated by different ligands and by interaction of p75NTR with different coreceptors. Our results suggest that blocking the signaling through RAGE–p75NTR complex constitutes an alternative to selectively prevent p75NTR-mediated motor neuron death, without affecting its beneficial effects.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

All chemical and reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich unless otherwise specified. Culture media, serum, and supplements were obtained from Life Technologies, unless otherwise specified. l-NAME, Fas (human):Fc (human), PD169316, SD-169, and SB202190 were from Enzo Life Sciences. Z-VAD-FMK was obtained from R&D Systems. The RAGE antagonist peptides RAP and FPS-ZM1 were from Calbiochem-EMD Millipore. Human glycated albumin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. hBDNF was obtained from Alomone Labs. Blocking antibodies were rabbit polyclonal anti-NGF (#AB1526SP; EMD Millipore-Chemicon), goat polyclonal anti-RAGE antibody (AF1179; R&D Systems), and rabbit polyclonal anti-p75NTR (#AB-N01AP; Advanced Targeting Systems). As a control, we used normal goat IgG (AB-108-C; R&D Systems).

Animals

Transgenic mice overexpressing ALS-linked hSOD1G93A were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory strain B6.Cg-Tg(SOD1*G93A)1Gur/J (stock # 004435). RAGE knockout mice were previously described (38). Both transgenic lines were maintained in a C57BL/6J background. Genotype was determined by PCR. All animal procedures were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH. The Animal Care and Use Committee of MUSC (Animal Welfare Assurance number is A3428-01) approved the animal protocol pertinent to the experiments reported in this publication.

Methylglyoxal treatment

Mature NGF purified from mouse submaxillary glands (NGF 2.5S; #B.5017) was obtained from Harlan Bioproducts. NGF, 0.2 mg/mL in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, was treated with vehicle (control) or MG (2 or 4 μM final concentration) for 48 h at 37°C, under sterile conditions. Residual MG was eliminated by ultrafiltration using Amicon Ultra-0.5 devices, after reconstituting the concentrate to the original sample volume four times with phosphate buffered saline. For the dose response experiments, samples were treated with different concentrations of MG (0.5–500 μM) as already indicated, for 72 h at 37°C. For the time response experiments, samples were treated with MG (4 μM final concentration) and incubated for 1, 2, 4, or 6 days at 37°C. After incubation, samples were diluted in reducing Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot as described hereunder.

Peroxynitrite treatment

Peroxynitrite was synthesized as previously described (50). Peroxynitrite concentration was determined by absorbance at 302 nm in 1 M NaOH (ɛ = 1670 M−1 cm−1). Diluted stock solutions were freshly prepared in 0.01 M NaOH. NGF (0.2 mg/mL) was treated with peroxynitrite (1 mM final concentration) as previously described (45). The reaction was performed in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20 mM sodium bicarbonate. Peroxynitrite was added to the sample in 10 bolus of 1 μL each, to reach a final concentration of 1 mM. Control experiments were performed using diluted NaOH or decomposed peroxynitrite.

Cell culture and treatment

Human neuroglioma (H4) and mouse motor neuron-like (NSC-34) cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 IU/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Stable transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies), and the culture media were supplemented with 350 μg/mL G418 sulfate (Corning) and 200 μg/mL hygromycin B. All cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Primary astrocyte cultures were prepared from the spinal cord of 1-day-old mice as we previously described (43). Pups were cold anesthetized and then euthanized by decapitation. Astrocytes were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS, HEPES (3.6 g/L), penicillin (100 IU/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL). Cultures were >98% pure as determined by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, an astrocytic marker) immunoreactivity and devoid of CD11b-positive microglial cells.

Motor neuron cultures were prepared from mouse embryonic spinal cords (E12.5) as previously described (42). To prepare hSOD1G93A or RAGE knockout motor neurons, genotyping was performed by real time-PCR during dissection, and all embryos of the same genotype were pooled together for the rest of the preparation. Motor neurons were plated at a density of 500 cells/cm2 on four-well multidishes (Nunclon) precoated with polyornithine–laminin. Cultures were maintained in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% horse serum, 25 μM l-glutamate, 25 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM l-glutamine, 2% B-27 supplement, and GDNF (1 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich). Motor neuron death induced by trophic factor deprivation (NONE, without GDNF) was determined in all experiments as a control and was never >50%. Motor neuron survival was assessed by direct counting of all neurons displaying intact neurites longer than four cell bodies in diameter, as previously described (45).

For coculture experiments, motor neurons were plated on mouse astrocyte monolayers at a density of 300 cells/cm2 and maintained in L15 medium supplemented with 0.63 mg/mL bicarbonate, 5 μg/mL insulin, 0.1 mg/mL conalbumin, 0.1 mM putrescine, 30 nM sodium selenite, 20 nM progesterone, 20 mM glucose, 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2% horse serum (43). Motor neurons were identified by immunostaining with antineurofilament 160 (mouse monoclonal [clone NN18]; #N5264; Sigma-Aldrich). Survival was determined by direct counting of all neurofilament-positive cells, as previously described (42). Counts were performed over an area of 0.90 cm2 in 24-well plates.

Primary cortical neuronal cultures were prepared from mouse embryonic cortices (E15) as we previously described (42). Cells were plated at a density of 1.5 × 105 cells/cm2 and maintained in Neurobasal medium supplemented with 1% B-27 and 0.5 mM glutamine. Cells were harvested on the 7th day after plating. Cultures were >98% pure as judge by βIII-tubulin and GFAP staining.

Plasmid constructs

The cDNA of human RAGE (NM_001136) with a C-terminal Myc-DDK tag in the expression vector pCMV6-Entry (#RC204664) was obtained from OriGene. The cDNA of human p75NTR (NM_002507) with a C-terminal His tag in the expression vector pReceiver-M77 (#EX-A0100-M77) was obtained from GeneCopoeia. The p75NTR cDNA was then cloned into the expression vector pCMV6-A-Hygro (#PS100024; OriGene).

Lumbar spinal cord extracts

Lumbar spinal cords were dissected, over ice under sterile conditions, from early symptomatic hSOD1G93A mice (≈100-day-old) or aged-matched nontransgenic littermates. One hundred milligrams of tissue was processed in 0.4 ml of ice-cold PBS containing 3 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, and complete, EDTA-free, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Applied Science). Tissue was then homogenized under sterile conditions and homogenates were centrifuged at 40,000 g for 1 h. Supernatants were collected and kept at −80°C until used. Aliquots were added to motor neuron cultures to reach a final protein concentration of 0.5 μg/mL.

Size-exclusion chromatography

Samples of NGF at a concentration of 0.2 mg/mL were treated with vehicle or MG (500 μM) for 3 days as already indicated. Aliquots containing 10 μg of vehicle-treated NGF or NGF-MG were manually injected onto a 50 μl injection loop connected to an Agilent 1100 Series pump (Agilent Technologies) equipped with a XBridge Protein BEH SEC 125 Å, 3.5 μm, 7.8 × 150 mm column (Waters). The outlet of the column was connected to a Waters 2487 Dual Absorbance UV/Visible detector. The pump was run isocratically at 0.5 ml/min at room temperature. The buffer used was 50 mM sodium phosphate/50 mM sodium sulfate, pH 7.2. Elution of NGF was determined by absorbance at λ = 220 nm. Fractions corresponding to NGF elution were manually collected at the outlet of the detector and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Identification of modified residues by tandem mass spectrometry

NGF at a concentration of 0.2 mg/mL was treated with MG (4 μM) for 3 days as already indicated. Samples (10 μg) were reduced in 10 mM dithiothreitol (Thermo Scientific), and alkylated in 25 mM iodoacetamide (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h at 25°C in the dark. Samples were digested with 1 μg of porcine trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) (1:10, enzyme:protein ratio) or 1 μg of Glu-C (Thermo Scientific) (1:10, enzyme:protein ratio). Before trypsin digestion, 1 M ammonium bicarbonate was added to a 100 mM final concentration. The Glu-C digestion was done in 1 × buffer phosphate (pH 7.4). Both digestions were incubated overnight at 25°C with mild agitation. Reactions were quenched with 10% trifluoroacetic acid. Peptides were desalted using C18 ZipTip® pipette tips (Millipore). Peptides were dissolved in solvent A and loaded on a trap column (C18 pepMap 100, 300 μm × 5 mm) (Thermo Scientific) and separated on a 75 μm × 20 cm analytical column packed in house with C18 YMC ODS-AQ (Waters Corp.) using a 180 min gradient (from 5% B to 50% B). Solvent A was 2% acetonitrile (ACN)/0.2% formic acid (FA); solvent B was 98% ACN/2% FA. Eluting peptides were mass analyzed by data-dependent acquisition on the Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) with Xcalibur 2.2 software. The top 20 most intense ions detected in the survey mass spectrum (Orbitrap detector at 60,000 resolution, mass range 400–1700 Da, target value of 1 × 106) were selected for fragmentation by collision-induced dissociation at 35% normalized collision energy. Fragments were detected in the ion trap. Ions with a +1 charge were excluded from selection. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of 2, duration of 30 s, exclusion list size of 50, and exclusion duration of 120 s.

Database searching and peptide identification

The tandem mass spectra were searched using SequestHT within Proteome Discoverer (PD) 1.4 (Thermo Scientific) against a Uni Prot (Swiss Prot + Tremble) mouse (taxonomy # 10090) protein database containing isoforms (77,220 sequences, downloaded on March 13, 2015). Parameters for peptide identification were as follows: precursor mass tolerance of 20 ppm, fragment mass tolerance of 0.8 Da, fully tryptic peptides with a maximum of three missed cleavages, and carbamidomethyl static modification of cysteine residues. Variable modifications for arginine (R) were the hydroimidazolone derivate (MG-H1/2/3; +54.011 Da), argpyrimidine (+80.026 Da), THP (+144.042 Da), and dihydroxyimidazolidine (+72.021 Da). Carboxyethyl lysine (+72.021 Da) and methionine oxidation (+15.995 Da) were also included as variable modifications. The search results were filtered to yield only high confidence peptides (1% false discovery rate) using the “target decoy validator” feature in PD 1.4. Identified peptides had mass errors <5 ppm. Fragment-labeled spectra were exported from PD 1.4; raw spectra were exported from Xcalibur 2.2. Modification sites were verified manually.

Production of monoclonal antibody against nitrated NGF

The specific mouse monoclonal antibody against nitrated NGF was produced by GenScript using as immunogen the peptide corresponding to NGF residues 48–58 with a nitrated tyrosine residue at position 52 [VFKQY(NO2)FFETKC]. The peptide was conjugated to the carrier protein keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Balb/c mice were immunized and hybridoma cell lines were generated. Antibodies were screened by ELISA for binding to the immunogen (nitrated NGF48-58 peptide) and nitrated NGF and for lack of binding to the non-nitrated NGF48-58 peptide.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis

Spinal cord protein extracts were prepared in Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.6 supplemented with 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail EDTA free. After sonication, samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 10,000 g. Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method (BCA protein assay; Thermo Scientific-Pierce). For immunoprecipitation, 1 mg of protein extracts in lysis buffer was incubated overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal antibody anti-NGF (H-20) (#sc-548; rabbit anti- Santa Cruz). After adding BioMag Plus protein A magnetic particles (Polysciences, Inc.), the incubation was extended for 1 h. After washing three times with lysis buffer, immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by incubation for 5 min at 95°C in 2 × concentrated reducing Laemmli sample buffer.

Immnoprecipitated proteins, protein extracts, or NGF samples were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels or 4–15% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ gels (BioRad) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes using the Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (BioRad). Membranes were blocked for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline (TBS), 0.1% Tween-20, and 5% bovine serum albumin, followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C with the primary antibody diluted in the same buffer. After washing with 0.1% Tween-20 in TBS, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (GE Healthcare) for 1 h at room temperature. For immunodetection of immunoprecipitated proteins, membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with clean blot IP detection reagent (HRP) (#21230; Thermo Scientific) or peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG light chain-specific antibody (#115-005-174; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.). Membranes were then washed and developed using the ECL Prime chemiluminescent detection system (GE Healthcare). Membranes were imaged and quantified using the C-DiGit Blot Scanner (LI-COR Biosciences). Protein loading was corrected by β-Actin or α-Tubulin levels.

The following primary antibodies were used for Western blot experiments: mouse monoclonal anti-β-Actin (clone AC-15; #A5441; Sigma-Aldrich); mouse monoclonal anti-AGE-4 (clone 14B5; #KAL-KG133; Cosmo Bio USA, Inc.); rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH (#ab9485; Abcam); mouse monoclonal anti-6-Histidine epitope tag (clone AD1.1.10; #NB100-64768; Novus Biologicals); mouse monoclonal anti-c-Myc (clone 9E10; #M4439; Sigma-Aldrich); rabbit polyclonal anti-NGF (#AB1526SP; EMD Millipore-Chemicon); rabbit polyclonal anti-NGF (#AN-240; Alomone Labs); rabbit monoclonal anti-p75 (clone EP1039Y; #NB110-58000 Novus Biologicals or #GTX61425; or GeneTex); rabbit polyclonal anti-proNGF (#ANT-005; Alomone Labs); rabbit polyclonal anti-RAGE (#R5278; Sigma-Aldrich); rabbit polyclonal anti-RAGE (#ab37647; Abcam); mouse monoclonal anti-α-Tubulin (clone DM1A; #3873; Cell Signaling Technology).

Crosslinking and coimmunoprecipitation

Cells were incubated in Hank's balanced salt solution for 30 min at room temperature with the membrane-impermeable reducible crosslinker DTSSP (5 mM; Thermo Scientific-Pierce). The reaction was stopped by addition of 1 M Tris, pH 7.5, to a final concentration of 50 mM. Cells were lysed in Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.6 supplemented with 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.25% Nonidet P-40, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail EDTA free. After incubation on ice, samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min at 10,000 g. Immunoprecipitation was performed using the following specific antibodies: rabbit monoclonal anti-p75 (clone EP1039Y; #GTX61425), mouse monoclonal anti-6-Histidine epitope tag (clone AD1.1.10; #NB100-64768; Novus Biologicals), or the c-Myc-tagged protein mild purification kit Ver.2 (#3305; MBL International Corporation). Precipitated complexes were analyzed by Western blot as already described.

Immunofluorescence and in situ PLA

Motor neuron cultures, maintained for 48 h as already indicated, were fixed on ice with 4% paraformaldehyde plus 0.1% glutaraldehyde in PBS. Cultures were immunostained with antibodies against the extracellular domain of p75NTR (mouse monoclonal [MLR2 clone], #ab61425; Abcam) and RAGE (rabbit polyclonal, #ab37647; Abcam), and developed using (i) Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat antimouse (#A-11032; Life Technologies) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antirabbit (#A-11034; Life Technologies) for immunofluorescence analysis or (ii) DuoLink In Situ PLA Probe Anti-Rabbit PLUS (#DUO92002) and Anti-Mouse MINUS (#DUO92004) with the DuoLink In Situ Detection Reagents Red (#DUO92008) (Sigma-Aldrich) for PLA. Negative controls omitting independently one or both primary antibodies were performed in each experiment. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Life Technologies). The signal from each detected pair of PLA probes was observed in an Olympus Fluoview FV10i laser scanning desktop microscope. For analysis of p75NTR and RAGE colocalization by immunofluorescence, samples were imaged with a Zeiss LSM 880 NLO Axioobserver inverted laser scanning confocal/multiphoton microscope using a 63 × 1.4 N.A. Plan-Apochromat oil immersion DIC lens. Fluorescence of DAPI, Alexa Fluor 488, and Alexa Fluor 594 was excited at 405 nm, 488 nm, and 561 nm, respectively, and detected at 410–496 nm, 499–588 nm, and 600 nm, respectively at a 1-Airy-unit-diameter pinhole. The 0.38 μm thick z-stack images were processed using Zeiss Zen software.

Statistical analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SEM. Significance was determined using either Student's t-test, or for multiple group comparison one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test. When comparing the effect of genotype and treatments, two-way ANOVA was used followed by Bonferroni's post-test. Differences were declared statistically significant if p < 0.05. All statistical computations were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software).

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- AGEs

advanced glycation end products

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- CEL

Nɛ-carboxyethyl lysine

- FALS

familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- FasL

Fas ligand

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GDNF

glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GLO1

glyoxalase I

- GSH

glutathione

- HGA

glycated human albumin

- IP

immunoprecipitation

- l-NAME

Nω-nitro l-arginine methyl ester

- MG

methylglyoxal

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- p75NTR

p75 neurotrophin receptor

- PLA

proximity ligation assay

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end products

- SALS

sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- SOD1

Cu–Zn superoxide dismutase

- Trk

tropomyosin-related tyrosine kinase receptor

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS100835, GM103542, and Shared instrumentation grants S10 D010731 and S10 OD018113. Mice were housed in a facility constructed with support from the NIH, Grant Number C06 RR015455 from the Extramural Research Facilities Program of the National Center for Research Resources. This work used the Cell and Molecular Imaging Shared Resource, Hollings Cancer Center, Medical University of South Carolina (P30 CA138313). LC-MS/MS analysis was performed at the MUSC Mass Spectrometry Facility, supported by the Office of the Provost and the South Carolina COBRE in Oxidants, Redox Balance, and Stress Signaling.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Gomez SB, Schmidt AM, and Logsdon CD. S100P-derived RAGE antagonistic peptide reduces tumor growth and metastasis. Clin Cancer Res 18: 4356–4364, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber SC. and Shaw PJ. Oxidative stress in ALS: key role in motor neuron injury and therapeutic target. Free Radic Biol Med 48: 629–641, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker PA. p75NTR is positively promiscuous: novel partners and new insights. Neuron 42: 529–533, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bothwell M. NGF, BDNF, NT3, and NT4. Handb Exp Pharmacol 220: 3–15, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruno MA. and Cuello AC. Cortical peroxynitration of nerve growth factor in aged and cognitively impaired rats. Neurobiol Aging 33: 1927–1937, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruno MA, Leon WC, Fragoso G, Mushynski WE, Almazan G, and Cuello AC. Amyloid beta-induced nerve growth factor dysmetabolism in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 68: 857–869, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Iavicoli I, Di Paola R, Koverech A, Cuzzocrea S, Rizzarelli E, and Calabrese EJ. Cellular stress responses, hormetic phytochemicals and vitagenes in aging and longevity. Biochim Biophys Acta 1822: 753–783, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassina P, Pehar M, Vargas MR, Castellanos R, Barbeito AG, Estevez AG, Thompson JA, Beckman JS, and Barbeito L. Astrocyte activation by fibroblast growth factor-1 and motor neuron apoptosis: implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem 93: 38–46, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cassina P, Peluffo H, Pehar M, Martinez-Palma L, Ressia A, Beckman JS, Estevez AG, and Barbeito L. Peroxynitrite triggers a phenotypic transformation in spinal cord astrocytes that induces motor neuron apoptosis. J Neurosci Res 67: 21–29, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casula M, Iyer AM, Spliet WG, Anink JJ, Steentjes K, Sta M, Troost D, and Aronica E. Toll-like receptor signaling in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis spinal cord tissue. Neuroscience 179: 233–243, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chao MV. and Bothwell M. Neurotrophins: to cleave or not to cleave. Neuron 33: 9–12, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman AL, Winterbourn CC, Brennan SO, Jordan TW, and Kettle AJ. Characterization of non-covalent oligomers of proteins treated with hypochlorous acid. Biochem J 375: 33–40, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou SM, Wang HS, Taniguchi A, and Bucala R. Advanced glycation endproducts in neurofilament conglomeration of motoneurons in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Med 4: 324–332, 1998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Covaceuszach S, Konarev PV, Cassetta A, Paoletti F, Svergun DI, Lamba D, and Cattaneo A. The conundrum of the high-affinity NGF binding site formation unveiled? Biophys J 108: 687–697, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dattilo S, Mancuso C, Koverech G, Di Mauro P, Ontario ML, Petralia CC, Petralia A, Maiolino L, Serra A, Calabrese EJ, and Calabrese V. Heat shock proteins and hormesis in the diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Immun Ageing 12: 20, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deane R, Singh I, Sagare AP, Bell RD, Ross NT, LaRue B, Love R, Perry S, Paquette N, Deane RJ, Thiyagarajan M, Zarcone T, Fritz G, Friedman AE, Miller BL, and Zlokovic BV. A multimodal RAGE-specific inhibitor reduces amyloid beta-mediated brain disorder in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest 122: 1377–1392, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deinhardt K. and Chao MV. Trk receptors. Handb Exp Pharmacol 220: 103–119, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferraiuolo L, Higginbottom A, Heath PR, Barber S, Greenald D, Kirby J, and Shaw PJ. Dysregulation of astrocyte-motoneuron cross-talk in mutant superoxide dismutase 1-related amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 134: 2627–2641, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz G. RAGE: a single receptor fits multiple ligands. Trends Biochem Sci 36: 625–632, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gandelman M, Levy M, Cassina P, Barbeito L, and Beckman JS. P2X7 receptor-induced death of motor neurons by a peroxynitrite/FAS-dependent pathway. J Neurochem 126: 382–388, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hempstead BL. Deciphering proneurotrophin actions. Handb Exp Pharmacol 220: 17–32, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson CE, Camu W, Mettling C, Gouin A, Poulsen K, Karihaloo M, Rullamas J, Evans T, McMahon SB, Armanini MP, Berkemeier L, Phillips HS, and Rosenthal A. Neurotrophins promote motor neuron survival and are present in embryonic limb bud. Nature 363: 266–270, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland DR, Cousens LS, Meng W, and Matthews BW. Nerve growth factor in different crystal forms displays structural flexibility and reveals zinc binding sites. J Mol Biol 239: 385–400, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilieva H, Polymenidou M, and Cleveland DW. Non-cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond. J Cell Biol 187: 761–772, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ischiropoulos H. and Beckman JS. Oxidative stress and nitration in neurodegeneration: cause, effect, or association? J Clin Invest 111: 163–169, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Juranek JK, Daffu GK, Wojtkiewicz J, Lacomis D, Kofler J, and Schmidt AM. Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products and its Inflammatory Ligands are Upregulated in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Cell Neurosci 9: 485, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato S, Horiuchi S, Liu J, Cleveland DW, Shibata N, Nakashima K, Nagai R, Hirano A, Takikawa M, Kato M, Nakano I, and Ohama E. Advanced glycation endproduct-modified superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1)-positive inclusions are common to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients with SOD1 gene mutations and transgenic mice expressing human SOD1 with a G85R mutation. Acta Neuropathol 100: 490–505, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kichev A, Ilieva EV, Pinol-Ripoll G, Podlesniy P, Ferrer I, Portero-Otin M, Pamplona R, and Espinet C. Cell death and learning impairment in mice caused by in vitro modified pro-NGF can be related to its increased oxidative modifications in Alzheimer disease. Am J Pathol 175: 2574–2585, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kierdorf K. and Fritz G. RAGE regulation and signaling in inflammation and beyond. J Leukoc Biol 94: 55–68, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koliatsos VE, Crawford TO. and Price DL. Axotomy induces nerve growth factor receptor immunoreactivity in spinal motor neurons. Brain Res 549: 297–304, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraemer BR, Yoon SO, and Carter BD. The biological functions and signaling mechanisms of the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Handb Exp Pharmacol 220: 121–164, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kust BM, Brouwer N, Mantingh IJ, Boddeke HW, and Copray JC. Reduced p75NTR expression delays disease onset only in female mice of a transgenic model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 4: 100–105, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowry KS, Murray SS, McLean CA, Talman P, Mathers S, Lopes EC, and Cheema SS. A potential role for the p75 low-affinity neurotrophin receptor in spinal motor neuron degeneration in murine and human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord 2: 127–134, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu B, Pang PT, and Woo NH. The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 603–614, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maida V, Bennardini F, Bonomi F, Ganadu ML, Iametti S, and Mura GM. Dissociation of human alphaB-crystallin aggregates by thiocyanate is structurally and functionally reversible. J Protein Chem 19: 311–318, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meeker RB. and Williams KS. The p75 neurotrophin receptor: at the crossroad of neural repair and death. Neural Regen Res 10: 721–725, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller FD. and Kaplan DR. Life and death decisions: a biological role for the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Cell Death Differ 5: 343–345, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myint KM, Yamamoto Y, Doi T, Kato I, Harashima A, Yonekura H, Watanabe T, Shinohara H, Takeuchi M, Tsuneyama K, Hashimoto N, Asano M, Takasawa S, Okamoto H, and Yamamoto H. RAGE control of diabetic nephropathy in a mouse model: effects of RAGE gene disruption and administration of low-molecular weight heparin. Diabetes 55: 2510–2522, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagai M, Re DB, Nagata T, Chalazonitis A, Jessell TM, Wichterle H, and Przedborski S. Astrocytes expressing ALS-linked mutated SOD1 release factors selectively toxic to motor neurons. Nat Neurosci 10: 615–622, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Narhi LO, Rosenfeld R, Talvenheimo J, Prestrelski SJ, Arakawa T, Lary JW, Kolvenbach CG, Hecht R, Boone T, Miller JA, and Yphantis DA. Comparison of the biophysical characteristics of human brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophin-3, and nerve growth factor. J Biol Chem 268: 13309–13317, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nykjaer A, Lee R, Teng KK, Jansen P, Madsen P, Nielsen MS, Jacobsen C, Kliemannel M, Schwarz E, Willnow TE, Hempstead BL, and Petersen CM. Sortilin is essential for proNGF-induced neuronal cell death. Nature 427: 843–848, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pehar M, Beeson G, Beeson CC, Johnson JA, and Vargas MR. Mitochondria-targeted catalase reverts the neurotoxicity of hSOD1G(9)(3)A astrocytes without extending the survival of ALS-linked mutant hSOD1 mice. PLoS One 9: e103438, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pehar M, Cassina P, Vargas MR, Castellanos R, Viera L, Beckman JS, Estevez AG, and Barbeito L. Astrocytic production of nerve growth factor in motor neuron apoptosis: implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurochem 89: 464–473, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pehar M, Vargas MR, Robinson KM, Cassina P, Diaz-Amarilla PJ, Hagen TM, Radi R, Barbeito L, and Beckman JS. Mitochondrial superoxide production and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 activation in p75 neurotrophin receptor-induced motor neuron apoptosis. J Neurosci 27: 7777–7785, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pehar M, Vargas MR, Robinson KM, Cassina P, England P, Beckman JS, Alzari PM, and Barbeito L. Peroxynitrite transforms nerve growth factor into an apoptotic factor for motor neurons. Free Radic Biol Med 41: 1632–1644, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabbani N, Ashour A, and Thornalley PJ. Mass spectrometric determination of early and advanced glycation in biology. Glycoconj J 33: 553–568, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rabbani N. and Thornalley PJ. Dicarbonyl proteome and genome damage in metabolic and vascular disease. Biochem Soc Trans 42: 425–432, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rabbani N. and Thornalley PJ. Dicarbonyl stress in cell and tissue dysfunction contributing to ageing and disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 458: 221–226, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rabbani N, Xue M, and Thornalley PJ. Activity, regulation, copy number and function in the glyoxalase system. Biochem Soc Trans 42: 419–424, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radi R, Beckman JS, Bush KM, and Freeman BA. Peroxynitrite oxidation of sulfhydryls. The cytotoxic potential of superoxide and nitric oxide. J Biol Chem 266: 4244–4250, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Raoul C, Buhler E, Sadeghi C, Jacquier A, Aebischer P, Pettmann B, Henderson CE, and Haase G. Chronic activation in presymptomatic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mice of a feedback loop involving Fas, Daxx, and FasL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 6007–6012, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Raoul C, Estevez AG, Nishimune H, Cleveland DW, deLapeyriere O, Henderson CE, Haase G, and Pettmann B. Motoneuron death triggered by a specific pathway downstream of Fas. potentiation by ALS-linked SOD1 mutations. Neuron 35: 1067–1083, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raoul C, Henderson CE, and Pettmann B. Programmed cell death of embryonic motoneurons triggered through the Fas death receptor. J Cell Biol 147: 1049–1062, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Renton AE, Chio A, and Traynor BJ. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat Neurosci 17: 17–23, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]