Abstract

Objective

To examine the feasibility and potential benefits of peer mentoring to improve the disease self-management and quality of life of individuals with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Methods

Peer mentors were trained and paired with up to three mentees to receive self-management education and support by telephone over 12 weeks. This study took place at an academic teaching hospital in Charleston, South Carolina. Seven quads consisting of one peer mentor and three mentees were matched based on factors such as age, area of residence, marital and work status. Mentee outcomes of self-management, health-related quality of life, and disease activity were measured using validated tools at baseline, mid-intervention, and post-intervention. Descriptive statistics and effect sizes were calculated to determine clinically important (>0.3) changes from baseline.

Results

Mentees showed trends toward lower disease activity (p=0.004) and improved health-related quality of life, in the form of decreased anxiety (p=0.018) and decreased depression (p=0.057). Other improvements in health-related quality of life were observed with effect sizes exceeding 0.3, but did not reach statistical significance. In addition, both mentees and mentors gave very high scores for perceived treatment credibility and service delivery.

Conclusion

The intervention was well received. Training, peer mentoring program, and outcome measures were demonstrated to be feasible with modifications. This provides preliminary support for the efficacy, acceptability, and perceived credibility of a peer mentoring approach to improve disease self-management and health-related quality of life in African American women with SLE. Peer mentoring may augment current rheumatological care.

Keywords: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, African American, Women, Peer Mentoring, Behavioral Intervention, Self-Management

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) causes functional disability, chronic pain and psychosocial distress in many who have the disease.[1] Once diagnosed, patients face an overwhelming range of biological, psychological and social issues such as disease course and severity (both of which are often unpredictable), their ability to cope with pain, as well as uncertainties about social and work issues.[2] Like other chronic diseases, responsibilities for daily management gradually shift from healthcare providers (HCPs) to patients. Adapting to SLE is complex, and patients require support and guidance throughout the disease process so they may learn to live with and self-manage their symptoms.

While individuals with SLE often share a complex and frustrating journey following diagnosis, this may be even more pronounced for African American women. In the United States, the highest lupus morbidity and mortality rates are among African American women.[3] SLE affects approximately 1 in 250 African American women of childbearing age, and African Americans overall have three to four times greater prevalence of lupus, risk of developing lupus at an earlier age, and lupus-related disease activity, damage, and mortality compared with Caucasians.[4] Some have positioned elevated rates of SLE in African American women in the context of “immune cognition”, and suggest that the disease severity, for these women, is a physical manifestation of patterns of stress, discrimination, and social disadvantage.[5] In addition to managing disease-specific stressors, it has been suggested that African Americans are exposed to a unique set of risk factors (e.g., high rates of unemployment, poverty, violent crime, incarceration, and homicide) at multiple transition points during their development and across the life course,[6, 7] and this accumulation of disadvantage potentially exhibits itself as worse outcomes. Perhaps due to discrimination, implicit medical bias, and structural barriers, African Americans report poorer SLE treatment adherence and outcomes, in addition to longer disease duration and greater disease activity.[8] Thus, it is important to address potentially modifiable risk factors for SLE to improve health status and reduce health disparities in this high risk group.

Studies that have explored adverse outcomes in SLE patients have acknowledged the role of understanding the medical regimen, trust in the provider, and communication with providers, which are impacted by patient subjective norms, cultural, social support networks, mental health, and education.[9] Effective disease self-management requires patients to hold a substantial amount of disease education, social support, self-efficacy, and trust—a large burden for a single individual. These trends are more pronounced in African Americans than Caucasians,[10] and consequently they are a group that health services often fail to engage.[11] Patient self-management, education and social support networks are encouraged as part of a holistic approach to disease management. Patient education and self-management is an arthritis ‘best practice’ and a key clinical practice guideline.[12] Evidence-based self-management interventions designed to enhance social support and provide health education, among lupus patients, have reduced pain, improved function, and delayed disability.[13] However, African Americans and women are still disproportionately impacted by SLE. Persistent disparities may be due to the non-responsiveness of existing programs to the unique needs and cultural context of African Americans and/or women with SLE.[14, 15]

Social support is particularly important to African American women, and there is evidence for the pivotal influence of social support on the way African American women perceive stressors, access health-promoting services, and engage in health-promoting activities.[16, 17] Peer support interventions fit within a social support model.[18] Within this model, peer support could reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness, provide information about accessing available health services and promote behaviors that positively improve personal health, well-being and health practices. Not only does peer support appear to be effective among those hardly reached, but evidence indicates that it may be more effective among these groups. In a recent review of peer support for the hardly reached, Sokol and Fisher (2016) observed that characteristics of hardly reached groups moderated the relationship between peer support and outcomes in a manner indicating greater benefit of peer support among those who were more disadvantaged (e.g., those with lower health literacy, self-management, medication adherence, self-efficacy, education, socioeconomic status, social support, and rural area of residence).[11]

Mentoring by trained peers reinforces self-management skills and activities and has led to enhanced patient engagement and resulted in improved outcomes among patients with chronic conditions.[19] The success of relationship-centered peer mentoring has been attributed to the non-hierarchical, reciprocal relationship that is created by sharing similar experiences and the tendency of peer mentoring relationships to be consistent with the individual’s social and cultural beliefs[20, 21]. A peer-to-peer mentoring program that aims to provide support based on the sharing of information and experiences may particularly benefit African American women with SLE. In studies of predominantly low income and minority populations, specifically, peer mentors have been shown to help support healthy behaviors including breast feeding, smoking cessation, increased physical activity, and maintenance of weight loss,[22, 23] along with improved medication adherence and blood glucose monitoring in trials of people with diabetes.[24, 25] These studies highlight the potential of peer mentoring as a culturally sensitive means to improving health behaviors and outcomes in low income and minority groups in whom trust in the health care system may be lower than in the general population.[15, 24] Peers who have experience in managing their lupus may be in a better position to share knowledge and experience with which others may often not be able to relate.[26] This can establish trust and in turn decrease disparities in health care outcomes. Currently, the major support programs that patients with SLE can access are the Arthritis Self-Management Program (ASMP) and Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP).[13] However, the standardized outlines cannot be personalized and the group formats limit one-on-one interactions that could be culturally tailored to address the unique needs of African American women with SLE.

In an earlier qualitative study of predominantly African American women with SLE from medically underserved communities, 69% favored a peer support intervention to improve care,[15] which provides additional rationale for using peer support in this population. There is also some evidence that peer mentoring has led to improvements in positive affect, sleep, social coping, and perception of bodily pain in rheumatic conditions, and previous studies have shown that individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) appear to benefit from relationships they can rely on for emotional support, information and tangible assistance. Whether a peer mentoring program may facilitate some of these benefits in patients with SLE has yet to be explored.[27, 28]

To bridge this gap in knowledge, we developed and implemented a peer mentoring program with trained mentors who were considered competent in the management of their SLE to provide modeling and reinforcement of disease self-management skills to other African American women with more poorly managed SLE. The goal of this approach was for them to more effectively navigate the diverse set of issues and challenges inherent in SLE, and help them self-manage their disease through a combination of educational and informal phone interactions with each other.

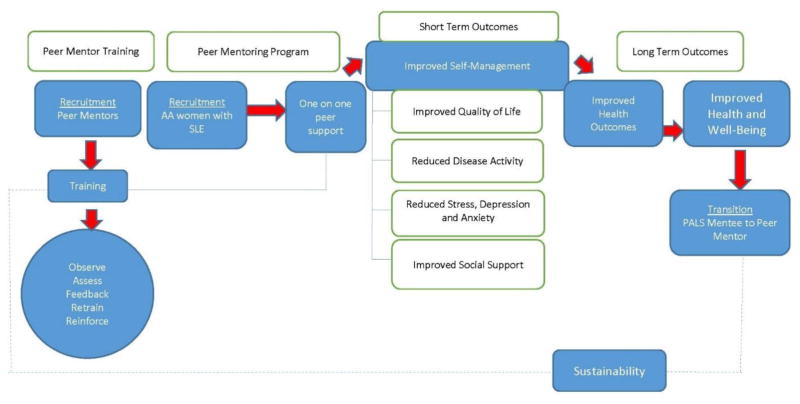

This study examines the: (1) feasibility and acceptability of a peer mentoring program among African American women with SLE and (2) changes in health-related quality of life, self-management, and disease activity outcomes as a result of this intervention (figure 1). The development phase of the study, to establish theoretical underpinnings, has been described elsewhere and included development of a qualitative literature search strategy on peer support and chronic diseases using MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CINAHL databases.[19] This paper reports on the feasibility and acceptability of the peer mentoring program and on the secondary outcome measures.

Figure 1.

Peer support intervention design.

METHODS

The Peer Approaches to Lupus Self-management (PALS) pilot project was an exploratory trial to test the feasibility of key intervention components, and included assessment of program effectiveness and considerations for long-term implementation and sustainability (Figure 1). This study complies with Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Internal Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Peer mentor recruitment and training

Potential mentees and mentors were recruited from those in the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) P60 MCRC longitudinal cohort who consented to contact about research and through physician referral. Flyers were posted in lupus clinics and research clinic space affiliated with MUSC and invitational letters were directly mailed to female African American patients in the MUSC lupus database. Mentors were identified by their MUSC rheumatologists as being competent to speak with the media on behalf of the patient population and deemed eligible if they scored a 7 or higher on the lupus self-efficacy scale (range=0–10) [29] at screening. Lupus self-efficacy was also assessed in mentees at screening, and those who scored 7 or higher were invited to serve as a mentor instead. Mentors and mentees were then selected based on additional inclusion criteria (box 1).

Box 1. Inclusion criteria for peer mentees and mentors.

| Mentees |

| 1) African American race/ethnicity and female gender |

| 2) Clinical diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) from a physician |

| 3) 18 years of age or older |

| 4) Able to provide informed consent and take part in ongoing assessment/evaluation activities (self-reported questionnaires, interviews, observation, activity logs |

| 5) Able to commit to duration of study (3 months) |

| 6) Demonstration of a lower level of coping/self-efficacy (score < 7, range=0–10); and 7) able to communicate in English |

| Mentors |

| 1) African American race/ethnicity and female gender |

| 2) Clinical diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) from a physician |

| 3) 18 years of age or older |

| 4) Able to provide informed consent and take part in ongoing assessment/evaluation activities (self-reported questionnaires, interviews, observation, activity logs) |

| 5) Able to commit to duration of study (3 months) |

| 6) Able to communicate in English |

| 7) Disease duration > 2 years |

| 8) Able to attend scheduled training sessions |

| 9) At least some college due to role that involves counseling, modeling, and delivering education |

| 10) Demonstration of a high level of coping/self-efficacy (score >/= 7, range=0–10) |

| 11) Willing to provide one-on-one support to up to three African American women with SLE |

| 12) PI determination of competence, maturity, emotional stability, and verbal communication skills after overall assessment during screening interview and training |

Eligibility screening occurred by telephone followed by face-to-face interviews with potential mentors and baseline study visit with mentees. Mentor interviews were conducted to assess maturity, emotional stability and verbal communication skills. As part of the mentor screening interview, psychosocial status was assessed using questions from the psychological scales of the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS),[30] the Arthritis Helplessness Index (AHI),[31] Wallston General Perceived Competence Scale,[31] University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale,[32] Campbell Personal Competence Index,[33] Carkhuff Communication and Discrimination Skills Inventories,[34] and the Applied Knowledge Assessment (AKA) scale.[34] These factors, combined with their self-efficacy score, indicated a higher level of disease self-management and necessary communication skills to serve as a mentor.

A mentor training manual was developed collaboratively with leadership of the Hospital for Special Surgery’s Lupusline, and prior to the start of the program, all peer mentors attended one 8-hour training session. Training provided information on SLE, educational/support resources and opportunities to learn and practice peer support techniques (informational, emotional, appraisal support) and skills (communication, decision-making, goal-setting). This session included the rationale for learning self-management, as well as how several factors can contribute to SLE disease burden. During training, mentors reviewed the mentor manual, including the outline of the format for calls and reporting requirements and detailed discussion of emergency situation procedures, practiced basic skills to use working with their mentees, such as communication strategies and role-playing exercises to reinforce skills, and participated in question development and topic starter exercises and problem solving exercises. Peer mentors received a resource binder with information on SLE and mentoring resources and ongoing support from the research team via email, telephone and in-person.

Pairing and delivery

Mentees were paired with peer mentors based on demographic information and personality assessments. Criteria used for the pairing process included disease symptoms, work-related concerns, life stage (marital status, children), demographic information like area of residence and age, personality characteristics, and availability. Following pairing, an introductory session was held and attended by mentee and mentor quads (1 mentor and their 3 assigned mentees). Topics of discussion included: the mentoring process, roles, responsibilities, benefits, and ground rules. Participants were also given the opportunity to ask any questions they may have had. If a face-to-face meeting at the intro session was not possible for all members of a quad (or triplet), a video meeting via Skype was arranged. The initial meeting was face-to-face, with subsequent meetings taking place at the discretion of the pair (in-person or telephone). Dyads interacted weekly for approximately 12 weeks. The intervention occurred by phone for 60 minutes per week for 12 weeks with optional additional interactions as long as they were documented.

Intervention Content

Weekly content was adapted from the six modules of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDMP), Arthritis Self-Management Program (ASMP), and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Self-Help (SLESH) Course,[13] and further tailored to African American women with six added sessions based on cultural issues reported as important to African Americans in earlier research conducted by the PI.[35] Descriptions for weekly content can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Weekly session content

| Week | Session Topic | Detailed Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Goal setting/action planning | Introduction to SLE management and a chance for the mentee to get to know the mentor |

| 2 | Exercise | Appropriate exercise for maintaining and improving strength, flexibility, and endurance |

| 3 | Medication overview | Appropriate use of medications and evaluation of new treatments/making informed decisions |

| 4 | Effective communication | Communicating effectively with family, friend, and health professionals |

| 5 | Nutrition/healthy eating | Sessions five will stress nutrition and healthy eating |

| 6 | Stress relaxation techniques | Relaxation techniques to cope with chronic pain, manage sudden increases in pain and other symptoms and reduce flares |

| 7 | Coping | Coping, including problem solving and strategies for coping with pain, other lupus symptoms, and interpersonal issues |

| 8 | Body image | Body image issues, including concerns around hair loss, skin discoloration and scaring, and medication-induced weight gain |

| 9 | Complications | Complications (e.g. kidney disease, digestive issues, pregnancy outcomes) fatalism-fear of complications and how that impacts perception of survival, and self-efficacy |

| 10 | Self-monitoring | Self-monitoring and depression |

| 11 | Sexuality/sexual health | Sexuality/sexual health, including spousal interactions and dating |

| 12 | Trust | Perceptions of care from doctor(s), impact on adherence, seeking second opinions, perceived discrimination, and perceived cultural competence of provider(s); Review of material from all previous sections; Feedback on program, discussion of any progress made |

Quantitative data collection

A one group pre-post design was used to determine changes over time. Peer mentors’ self-efficacy was assessed at eligibility screening (February 2016) via an interviewer-administered questionnaire, followed by a face-to-face interview with the PI to assess maturity, emotional stability, and communication skills at baseline (T1, February 2016). At mid-intervention or 6 weeks (T2, April 2016) and post-intervention or 12 weeks (T3, June 2016), peer mentors completed interviewer-administered questionnaires to determine the acceptability and feasibility of procedures, and to gain perspectives on the value of peer support. Mentee self-efficacy was also assessed at eligibility screening (February 2016) via an interviewer-administered questionnaire, followed by an initial study visit. Mentee outcome data were collected by interviewer-administered questionnaires and clinical assessment at baseline (T1, February 2016), mid-intervention or 6 weeks (T2, April 2016), and post-intervention or 12 weeks (T3, June 2016). Participants were brought together at the end for debriefing and celebrating.

Primary outcomes assessed included health-related quality of life, self-management, and disease activity. Health-related quality of life was captured using the five scales of the Lupus Quality of Life (LUP-QOL) measure which includes questions Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form 36 (SF-36) pertaining to physical function, role function, social function, mental health, health perception and pain.[36] Depression was assessed using the PHQ-9, a brief questionnaire that scores each of the 9 DSM-IV criteria for depression as “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day).[37] Anxiety was assessed using the 7-item General Anxiety Disorder (GAD) scale (GAD-7), which includes questions about worrying, restlessness, and irritability, using a scale from “0” (not at all) to “3” (nearly every day).[38] Perceived Stress was assessed using the perceived stress scale (PSS), which is a 4-item scale that assesses the degree to which the respondent finds situations stressful.[39] Lastly, the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOSSSS) was used to measure social support.[40] Self-Management was measured using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM), which assesses an individual’s knowledge, skill, and confidence for managing their health and healthcare.[41] Lastly, disease activity was assessed by self-report. The Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) is a validated patient reported version of the physician administered Systemic Lupus Activity Measure (SLAM).[42]

Process Measures (secondary outcomes) included scales for treatment credibility and satisfaction with care or service delivery. To assess differences in outcome expectancy, a modified treatment credibility scale developed by Borkovec and Nau (1972) was used. Satisfaction with care was measured with a previously validated general scale to measure satisfaction/dissatisfaction with health care. The 2-item scale ranges from 1 (Strongly Agree) to 5 (Strongly Disagree).

Other variables assessed as part of the peer mentoring intervention included demographic characteristics, health literacy, coping, and trust. Previously validated items from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey were used to capture age, marital status, education, household income, and health insurance. Health Literacy was measured using the Chew Health Literacy Screening Survey, a 3-item instrument designed to rapidly screen patients for potential health literacy problems.[43] Coping was assessed as lupus self-efficacy and was measured using the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale pain and other symptoms sub-scale,[29] which was reworded in previous investigations to reflect lupus rather than arthritis. Trust was measured using The Multidimensional Trust in Health Care Systems Scale (MTHCSS).[44]

Process measures and Qualitative Data

Implementation process data were collected to assess acceptability and feasibility. Weekly check-ins with peer mentors and mentees were conducted from March 2016–May 2016. The number and nature of meetings, topics discussed and problems arising were recorded by peer mentors via activity logs. Peer mentors met with the PI each week in the PI’s office to go over the activity logs, discuss any issues, concerns, or questions, and receive compensation. Research staff called mentees weekly for check-ins. One-on-one interviews with mentees were conducted to provide oversight of mentee/mentor interactions and check for adverse events. Finally, an end of study celebration and focus group was held in July 2016. Key themes from interviews were identified from transcribed data through constant comparison and have been reported elsewhere.[45]

Data Analysis

Feasibility Analysis

Important measures of feasibility included recruitment, compliance, and dropout proportions and participant satisfaction. Patient satisfaction with the peer mentoring intervention was evaluated using a likert-type satisfaction scale and determination of the proportions (along with CI) within the categories. For the continuous feasibility measures (e.g. treatment credibility, treatment adherence, peer mentoring phone sessions and attrition), frequency distributions and the median and mean responses (with 95% CIs) were obtained.

Quantitative Analysis

Mentee and mentor demographics are presented as N (%) and compared using a Fisher’s exact test. Patient reported outcomes are presented as least-square mean and standard error for both time points. Descriptive statistics and effect sizes from paired t-test results were calculated to determine clinically important (>0.3) changes. Effect size, a unitless measurement of treatment effect, was used to interpret the effects of the intervention. An effect size of 0.2 is considered small, 0.5 moderate and 0.8 large.[46] While it was important to capture effect sizes to demonstrate the clinical relevance of the intervention and outcomes assessed, statistical significant difference was the primary measurement. All numbers and statistical test results were obtained from repeated measures, mixed-effects linear regression models controlling for mentor. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4. Statistical significance was assessed at α = 0.05. Given the exploratory nature of this study, there was no correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Peer mentor recruitment and training

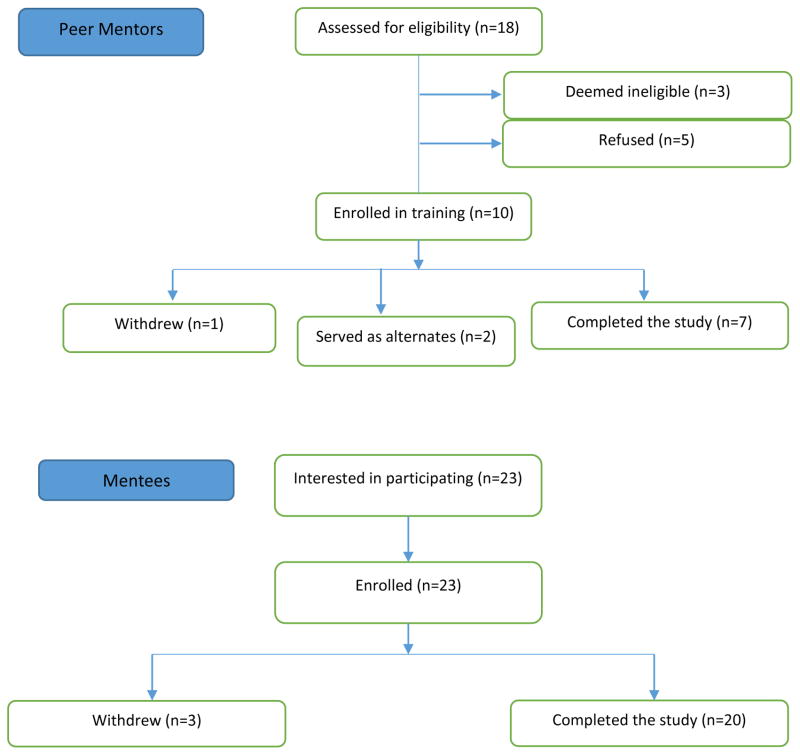

Letters were mailed to 450 potential mentees and 24 potential mentors. All mentors had SLE (see box 1). Eighteen potential mentors were identified, of whom 15 were eligible and 10 completed the training and became peer mentors. Two wanted to be maintained as back-ups and one withdrew due to personal illness and/or family issues.

Mentee recruitment

Twenty-three potential mentees were identified, all of whom were eligible and enrolled. All 23 mentees had SLE (see box 1). Three mentees were lost to follow-up and 20 completed the program (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram for peer mentor and mentee recruitment

Pairing and delivery

Seven mentor–mentee groups participated. The resulting study population included 20 mentees and 7 mentors leading to a 1:3 ratio in 6 groups, and a 1:2 ration in 1 group. All mentors and mentees were women.

Feasibility Findings

All 12 sessions were completed by all mentoring pairs, but 17 sessions were delayed and conducted later than originally scheduled, due to scheduling conflicts. An average of 1.24 (0.53) call attempts were made by mentors to their mentees each week. The average length of sessions was 54.1 min (range 0–105 min). The mode of contact after an initial face-to-face meeting was telephone only for all mentoring pairs. Both mentees and mentors gave very high scores for perceived treatment credibility and service delivery, with average scores for service delivery ranging from 3.89 to 4.51 on a scale of 0 to 5 and average scores for treatment credibility ranging from 6.28 to 7.88 on a scale of 0 to 10. Key themes revealed from interviews are reported elsewhere.[45]

Quantitative Results

Though not statistically significant, there was an improvement from baseline to follow-up in quality of life measures of physical function, role function, social function, mental health, health perception, pain, and social support, and in other measures of coping, health literacy, and trust, with effect sizes ranging from 0.01 to 0.27 (see Table 3). There was a significant decrease in health-related quality of life measures of anxiety [Diff = 3.52 (1.42); p = 0.018], and a marginally significant decrease in depression [Diff = 2.62 (1.33); p = 0.057]. There was no significant increase or decrease found in any of the self-management items, and the magnitude of effect sizes ranged from 0.00 to 0.25. For disease activity measures, there was a significant decrease in global rating of patient reported disease activity [Diff = 24.70 (7.62); p = 0.004]. Effect sizes for global rating of patient reported disease activity, anxiety, and depression were −0.74, −0.40, and −0.32, respectively. The remaining disease activity measures were not found to have changed significantly from baseline and the magnitude of effect sizes ranged from 0.01 to 0.37.

Table 3.

Least-square mean estimates, standard errors, test results, and effect sizes comparing baseline and post-intervention responses primary outcomes and covariates

| Mentees’ mean outcome scores at baseline (T1) and post-intervention (T2) | T1 | T2 | p value | Effect size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Measurement | Estimate SE | Estimate SE | Effect size T1–T2 (mean) | |||

| Quality of Life | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| ➢ Mental Health | 66.15 | 3.61 | 70.09 | 3.7 | 0.45 | 0.12 |

| ➢ Health Perception | 37.50 | 3.08 | 41.69 | 3.16 | 0.35 | 0.15 |

| ➢ Pain | 48.70 | 5.26 | 54.38 | 5.39 | 0.45 | 0.12 |

| ➢ Physical Function | 48.83 | 4.63 | 55.56 | 4.74 | 0.31 | 0.17 |

| ➢ Role Function | 59.66 | 5.48 | 64.94 | 5.61 | 0.50 | 0.11 |

| ➢ Social Function | 46.60 | 5.45 | 59.63 | 5.59 | 0.10 | 0.27 |

|

| ||||||

| Depression (PHQ-9) | 8.28 | 0.94 | 5.66 | 0.96 | 0.057 | −0.32 |

|

| ||||||

| Anxiety (GAD-7) | 7.72 | 0.99 | 4.2 | 1.02 | 0.018 | −0.40 |

|

| ||||||

| Stress (PSS) | 8.2 | 0.58 | 8.28 | 0.6 | 0.92 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Overall Social Support (MOSSS) | 56.98 | 2.89 | 60.82 | 2.96 | 0.36 | 0.15 |

|

| ||||||

| Self-management | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Patient Activation Measure (PAM) | 30.7 | 1.14 | 31.38 | 1.16 | 0.68 | 0.07 |

|

| ||||||

| Disease Activity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Systemic Lupus Activity Questionnaire (SLAQ) | ||||||

| ➢ Lupus flares | 1.37 | 0.23 | 0.94 | 0.24 | 0.21 | −0.30 |

| ➢ Lupus symptoms | 24.79 | 2.83 | 18.37 | 2.9 | 0.13 | −0.37 |

| ➢ Global rating-Disease activity | 32.36 | 5.36 | 7.66 | 5.5 | 0.004 | −0.74 |

|

| ||||||

| Other Variables | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Health Literacy (CHEW) | 5.47 | 0.41 | 5.49 | 0.42 | 0.97 | 0.01 |

| Coping (Lupus Self Efficacy Scale) | 346.86 | 26.01 | 312.87 | 26.66 | 0.37 | −0.15 |

| Trust (MTHCSS) | 38.27 | 1.23 | 37.89 | 1.26 | 0.83 | −0.04 |

All estimates and test results are from a repeated measures, mixed-effects linear regression models controlling for mentor.

SE: Standard Error

DISCUSSION

This study examined the feasibility and acceptability of a peer mentoring intervention that was culturally tailored to the unique needs of African American women, paired mentees with mentors who were race, gender, and SES concordant to facilitate bonding and social support, and used peer mentors who were considered competent in the management of their condition in order to provide modeling and reinforcement to participants. This study also examined changes in health-related quality of life, self-management, and disease activity outcomes as a result of this novel intervention that was meant to encourage mentees to engage in activities that promoted the learning of disease self-management skills and supported the mentees’ practice of these learned skills.

This study showed that a peer mentoring intervention was acceptable, feasible with modifications and well received by peer mentors and mentees. While weekly mentee/mentor contact was challenging, all sessions were completed and call durations were consistent with the intervention protocol. This suggests that the peer mentoring approach provides a viable solution to address persistent engagement and compliance issues in standardized programs. Many Arthritis Foundation chapters have had difficulty disseminating arthritis self-management education programs, and many vulnerable populations have not been included in study samples.[47–49] With regard to compliance, one study reported that less than 50% of a closed eligible population participated, even when Internet and small-group programs were offered repeatedly over many years,[50] suggesting that interventions may not be reaching the largest portion of lupus cases. Peer mentoring may circumvent barriers to participation and approach this problem in a real-world fashion, as it incorporates the documented needs and desires of the target population into the design.[15]

Results suggest that both mentors and mentees perceived benefits from the intervention. Mentees showed improvements in a number of outcome measures, including patient-reported disease activity, and health-related quality of life indicators of depression and anxiety. There was a small improvement in patient activation. Demonstration of a significant effect of the intervention on patient-reported disease activity (SLAQ) mirrors previous quantitative studies that have observed significant reductions in disease activity[24] following peer mentoring efforts among patients with chronic conditions.[19] Improvements in disease activity, health-related quality of life (in measures of anxiety and depression), and patient activation scores are encouraging since the main thrust behind the study was to develop an individualized peer mentoring program that was responsive to the needs of each patient and promoted disease self-management.

A limitation is the small sample size. Also, there was no control group in this study. However, this study was designed as a feasibility and pilot study. The goal was to obtain initial data for planning and implementing a larger scale study. As such, results from this preliminary pilot study are not meant to be generalized. Since weekly mentee/mentor contact was challenging, future iterations of the peer mentoring program will include bi-weekly sessions. Finally, a one month run-in period for mentors to work through call scheduling, practice intervention delivery over the phone and establish processes for follow-up may be beneficial to the success of the program, as study procedures had to be revisited with mentors a number of times at the outset of the study, following training.

Overall, this study provides evidence that peers can be instrumental in promoting self-management and improving one’s ability to cope with the diagnosis of a chronic disease. This was supported by both the findings reported herein and qualitative observations (reported elsewhere).[45] Peers also facilitate social support and may be a useful adjunct to standard rheumatological care. The information gleaned from this study has been incorporated into a randomized, controlled study comparing the ‘peer mentoring program’ with an ‘attention’ control group to further assess the benefits of peer mentoring in SLE management.

A peer mentoring program could help patients with SLE to navigate the issues surrounding their disease. The potential advantage of peer support relates to its focus on impacts on daily activities and functioning rather than on medical information.[20, 26] Peer support encourages sharing of experiences between participants with personalized and flexible content.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of Mentees and Mentors

| Variable | Mentee N (%) |

Mentorp N (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| <25 | 2 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.39 |

| 25–34 | 2 (8.7) | 3 (30.0) | |

| 35–44 | 8 (34.8) | 3 (30.0) | |

| 45–54 | 5 (21.7) | 1 (10.0) | |

| 55–64 | 1 (4.4) | 2(20.0) | |

| >65 | 5 (21.7) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 2 (8.7) | 3 (30.0) | 0.15 |

| Other | 21 (91.3) 8 (80.0) | ||

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 3 (13.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.65 |

| High school graduate | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Some College | 3 (13.7) | 2 (20.0) | |

| College graduate | 14 (63.6) 8 (80.0) | ||

| Income | |||

| <$15,000 | 5 (21.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.17 |

| $15,000–34,999 | 6 (26.1) | 3 (33.3) | |

| $35,000–64,999 | 5 (21.7) | 1 (11.1) | |

| > or=$65,000 | 2 (8.7) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Other/did not want to respond | 5 (21.7) | 1 (11.1) | |

Table 4.

Least-square mean estimates, standard errors, and effect sizes comparing mid-intervention and post-intervention responses for secondary outcomes measures

| Secondary Outcomes (Mentees and Mentors) | Mid-Intervention | SE | Post-Intervention | SE | P value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service delivery perception (/5) | ||||||

| How comfortable were you talking during your sessions? | 3.89 | 0.35 | 4.09 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 0.09 |

| How would you rate the quality of the communication during your sessions? | 4.29 | 0.15 | 4.29 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| How likely would you be to use this type of intervention if available? | 4.40 | 0.19 | 4.45 | 0.19 | 0.86 | 0.04 |

| How likely would you be to refer a family member or friend to this type of intervention? | 4.41 | 0.21 | 4.51 | 0.21 | 0.73 | 0.08 |

| How would you rate your overall satisfaction with this intervention? | 4.47 | 0.21 | 4.37 | 0.21 | 0.74 | −0.08 |

| Treatment credibility (/10) | ||||||

| How logical does this type of intervention seem to you? | 7.65 | 0.45 | 7.15 | 0.45 | 0.43 | −0.18 |

| How confident are you that this intervention will be successful for treating lupus? | 7.19 | 0.45 | 6.89 | 0.45 | 0.64 | −0.11 |

| How confident are you in recommending this intervention to a friend who has lupus? | 7.88 | 0.44 | 7.38 | 0.44 | 0.43 | −0.19 |

| How successful do you feel this intervention would be in decreasing the complications of lupus? | 7.38 | 0.56 | 6.28 | 0.56 | 0.18 | −0.32 |

All estimates are from a repeated measures, mixed-effects linear regression models controlling for mentor.

SIGNIFICANCE AND INNOVATIONS.

This is the first study to empirically test the effects of peer mentoring on self-management, health-related quality of life, and disease activity in African American women with SLE.

This study uses a culturally tailored combination of structured education and peer support to address barriers to disease self-management in the group most affected by SLE and its complications; African American women.

This pilot resulted in clinically relevant improvements in self-rated disease activity, depression, and anxiety.

Our findings suggest that a peer mentoring approach is feasible, acceptable, and effective in this vulnerable and understudied population.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the South Carolina Clinical & Translational Research (SCTR) Institute, with an academic home at the Medical University of South Carolina CTSA, NIH/NCATS Grant Number UL1, the Rheumatology and Immunology MCRC NIH/NIAMS Grant Number AR062755, NIH/NIAMS K23 AR052364, and NIH/NCRR UL1 RR029882. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, NIAMS, or NCATS.

We would like to thank the research participants for their contribution to this study. We also recognize the important role of the other members of the research team for their contribution to this project (Vernessa Nelson, Hetlena Johnson, Gailen Marshall, Denise Montgomery).

Footnotes

Contributors: EMW was the principal investigator and LE and JO were senior co-investigators. TF was involved in intervention development, implementation, evaluation, data analysis and manuscript writing. DV and MH were involved in data analysis and manuscript writing, and MG and VR provided statistical oversight. All authors read and approved the final version for publication.

Competing/conflicting interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rahman A, Isenberg D. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(9):929–939. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macejová Z, Záriková M, Oetterová M. Systemic lupus erythematosus--disease impact on patients. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2013;21(3):171–173. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a3818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcon GS, Scofield L, Reinlib L, Cooper GS. Understanding the epidemiology and progression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39(4):257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau CS, Yin G, Mok MY. Ethnic and geographical differences in systemic lupus erythematosus: an overview. Lupus. 2006;15(11):715–719. doi: 10.1177/0961203306072311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chae D, Drenkard C, Lewis T, Lim S. Discrimination and Cumulative Disease Damage Among African American Women With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2099–2107. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DRCC. Racial Residential Segregation- A Fundamental Cause of Racial Disparities in Health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116:404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cattell V. Poor people, poor places, and poor health: the mediating role of social networks and social capital. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52:1501–1516. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doninger N, Fink J, Utset T. Neuropsychologic functioning and health status in systemic lupus erythematosus: does ethnicity matter? J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11(5):250–256. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000182149.67967.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Achaval S, Suarez-Almazor M. Improving treatment adherence in patients with rheumatologic disease. The Journal of musculoskeletal medicine. 2010;27(10):1691476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Julian L, Yelin E, Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Trupin L, Criswell L, Katz P. Depression, Medication Adherence, and Service Utilization in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2009;61(2):240–246. doi: 10.1002/art.24236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokol R, Fisher E. Peer support for the hardly reached: A systematic review. AJPH. 2016;106(7):e1–e8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norgaard C. Managing lupus symptoms. JAAPA: Official Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2015;28(9):1. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000470449.19886.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorig K, Ritter P, Plant K. A disease-specific self-help program compared with a generalized chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2005;53(6):950–957. doi: 10.1002/art.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danoff-Burg SFF. Unmet Needs of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Behavioral Medicine. 2009;35:5–13. doi: 10.3200/BMED.35.1.5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman C, Bermas B, Zibit M, Fraser P, Todd D, Fortin P, Massarotti E, Costenbader K. Designing an intervention for women with systemic lupus erythematosus from medically underserved areas to improve care: a qualitative study. Lupus. 2013;22(1):52–62. doi: 10.1177/0961203312463979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin J, Thompson M, Kaslow N. The Mediating Role of Social Support in the Community Environment-Psychological Distress Link among Low-Income African American Women. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(4):459–470. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu C, Prosser R, Taylor J. Association of Depressive Symptoms and Social Support on Blood Pressure among Urban African American Women and Girls. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2010;22(12):694–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen S, Gottlieb B, Underwood L. Social support measurement and intervention. In: Cohen SGB, Underwood LG, editors. Measuring and intervening in social support. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams E, Egede L, Oates J. Effective self-management interventions for patients with lupus: potential impact of peer mentoring. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2017.01.011. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dennis C-L. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40:321–332. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, Bell M, Nyhof-Young J, Sale J, Britten N. The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: a qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson AK, Damio G, Chapman DJ, Perez-Escamilla R. Differential response to an exclusive breastfeeding peer counseling intervention: the role of ethnicity. J Hum Lact. 2007;23(1):16–23. doi: 10.1177/0890334406297182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas R, Lorenzetti D, Spragins W. Systematic review of mentoring to prevent or reduce tobacco use by adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(4):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philis-Tsimikas A, Fortmann A, Lleva-Ocana L, Walker C, Gallo L. Peerled diabetes education programs in high-risk Mexican Americans improve glycemic control compared with standard approaches: a Project Dulce promotora randomized trial. Diabetes care. 2011;34:1926–1931. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long J, Jahnle E, Richardson D, Loewenstein G, Volpp K. Peer mentoring and financial incentives to improve glucose control in African American veterans: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(6):416–424. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-6-201203200-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heisler M. Building Peer Support Programs to Manage Chronic Disease: Seven Models for Success. Oakland, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldenberg D, Payne L, Hayes L, Zeltzer L, Tsao J. Peer mentorship teaches social tools for pain self-management: A case study. J Pain Manag. 2013;6(1):61–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandhu S, Veinot P, Embuldeniya G, Brooks S, Sale J, Huang S, Zhao A, Richards D, Bell M. Peer-to-peer mentoring for individuals with early inflammatory arthritis: feasibility pilot. BMJ Open. 2013;3(3) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorig K, Chastain R, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman H. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1989;32(1):37–44. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meenan R, Gertman P, Mason J. Measuring health status in arthritis. The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:146–152. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein M, Wallston K, Nicassio P. Factor structure of the Arthritis Helplessness Index. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:427–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Russel D, Peplau L, Cutrona C. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers SOC Psychol. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Campbell A, Converse P, Miller W, Stokes E. The American Voter. New York, NY: Wiley; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carkhuff R. The Art of Helping: Trainer’s Guide. Amherst, MA: Human Resources Development Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams E, Penfield M, Kamen D, Oates J. An Intervention to Reduce Psychosocial and Biological Indicators of Stress in African American Lupus Patients: The Balancing Lupus Experiences with Stress Strategies Study. Open Journal Of Preventive Medicine. 2014;4(1):22–31. doi: 10.4236/ojpm.2014.41005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toloza S, Jolly M, Alarcón G. Quality-of-Life Measurements in Multiethnic Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Cross-Cultural Issues. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2010;12(4):237–249. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroenke K, Spitzer R. The PHQ-9: A new depression and diagnostic severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:509–521. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10) doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Oskamp S, editor. The Social Psychology of Health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherbourne C, Stewart A. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hibbard J, Mahoney E, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karlson E, Daltroy L, Rivest C, et al. Validation of a systemic lupus activity questionnaire (SLAQ) for population studies. Lupus. 2003;12:280–286. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu332oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker D, Williams M, Parker R, Gazmararian J, Nurse J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Egede L, Ellis C. Development and testing of the Multidimensional Trust in Health Care Systems Scale. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):808–815. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flournoy-Floyd M, Ortiz K, Oates J, Egede L, Williams E. “We Would Still Find Things to Talk About”: Assessment of Mentor Perspectives in a Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Intervention (Peer Approaches to Lupus Self-management-PALS), Empowering SLE Patients. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2017.05.003. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goeppinger J, Armstrong B, Schwartz T, Einsley D, Brady TJ. Self-management education for persons with arthritis: managing comorbidity and eliminating health disparities. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;57:1081–1088. doi: 10.1002/art.22896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edworthy SM, Dobkin PL, Clarke AE. Group psychotherapy reduces illness intrusiveness in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Rheumatology. 2003;30(5):1011–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haupt M, Millen S, Janner M, Falagan D, Fischer-Betz R, Schneider M. Improvement of coping abilities in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study. Annuals of Rheumatic Diseases. 2005;64(11):1618–1623. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bruce B, Lorig K, Laurent DD. Participation in patient self-management programs. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;2007:851–854. doi: 10.1002/art.22776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]